Anderson v. Martin Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Anderson v. Martin Jurisdictional Statement, 1962. 31c2f1c2-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9603ed5d-b91e-42e3-974f-74e28a051b51/anderson-v-martin-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

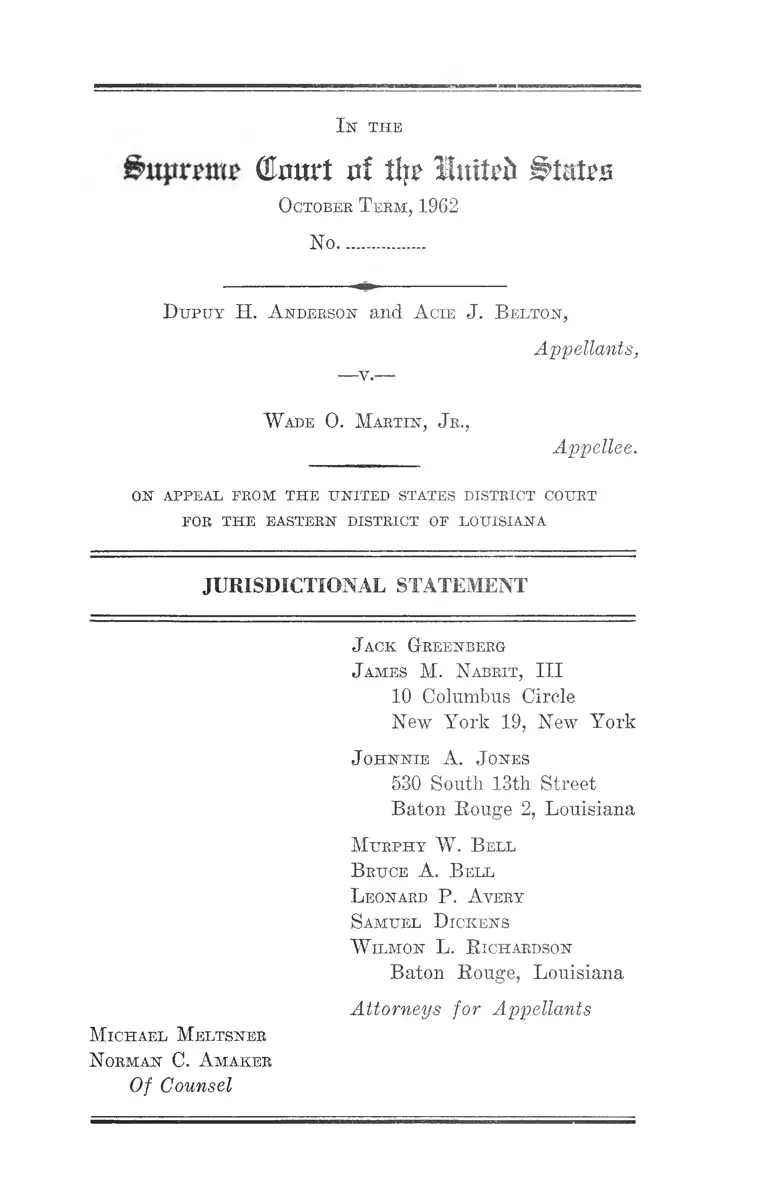

Is r t h e

(Esmxt of % lu itxb BtaUs

October T eem , 1962

No...............

D xjpxjy H. A nderson and A cie J. B elton ,

Appellants,

—v.—

W ade 0 . M artin , J r.,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

M ichael M eltsner

N orman C. A maker

Of Counsel

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

J o h n n ie A. J ones

530 South 13th Street

Baton Rouge 2, Louisiana

M u rph y W. B ell

B ruce A . B ell

L eonard P. A very

S amuel D ick ens

W ilm on L. R ichardson

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinion Below.............................................. 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................... 2

Statute Involved ............................................................ 2

Question Presented......................................................... 3

Statement of the Case..................................................... 4

The Question Presented Is Substantial ..................... 6

Co n c l u s io n ........................................................................................ 12

A ppendix ............................................................................................. 13

Opinions Below.............................................................. 13

Judgment ....................................................................... 24

T able of Cases

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .............. 10

Florida Lime and Avocado Growers v. Jacobsen, 362

U. S. 73 ....................................................................... 2

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157................................. 9

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp.

649 (E. X). La. 1961), affd 368 U. S. 515................. 9

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81 ................. 9

11

PAGE

Kessler y. Department of Public Safety, 369 II. S. 153 2

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214................. 8

McDonald v. Key, 125 F. Supp. 775 (W. D. Olda.,

1954)...................................................... ...................... 6, 7

McDonald v. Key, 224 F. 2d 608 (10th Cir. 1955), cert,

denied 350 U. S. 895 ................................................. 6, 7, 8

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ........................ 11

Nixon y. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ................................... 11

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ................................ 10

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ......... 10

United States v. Reese, 92 U. S. 214............................ 11

S tatutes

28 United States Code, §1253 ................................ 2

28 United States Code, §§1331, 1343(3) ................. 2

28 United States Code, §§2281, 2284 ..................... 2

42 United States Code, §§1971a, 1981, 1983 .......... 2

La. R. S. 18:117.1 ..............................................2, 3, 6, 9

Is r t h e

Bupnm? Glimrt of % HUmtvb Staten

October T erm , 1962

No...............

D u pu y H. A nderson and A cie J. B elton ,

Appellants,

W ade O. M artin , J r.,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants, Dupuy H. Anderson and Acie J. Belton, ap

peal from the order of the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana entered on October

3, 1962 denying a permanent injunction against the en

forcement of a statute of the State of Louisiana which

requires the designation of the race of candidates for elec

tive office on nominating papers and ballots. They submit

this statement to show that the Supreme Court of the

United States has jurisdiction of the appeal and that a

substantial question is presented.

Citation to Opinion Below

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana (R. 53) denying a prelimi

nary injunction was rendered on June 29, 1962 and is re-

2

ported at 206 F. Supp. 700. The dissenting opinion of

Circuit Judge Wisdom (R. 50) is reported at 206 F. Supp.

705. These opinions are reprinted in the appendix hereto

at pp. 13 and 21, respectively. No further opinion was

rendered with the final order, entered Oct. 3, 1962 (R. 70).

Jurisdiction

This suit was initiated in the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana to enjoin the

enforcement of La. R. S. §18:1174.1 (Act No. 538 of the

1960 Regular Session of the Louisiana Legislature). It

was brought pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §§1331, 1343(3) and

42 U. S. C. §§1971a, 1981, 1983, and was heard by a three

judge court convened under 28 U. S. C. §§2281 and 2284.

The order of the District Court denying the prayer for

issuance of a permanent injunction is dated September 28,

1962 and the time of its entry is October 3, 1962 (R. 70;

see appendix infra, p. 24). Notice of Appeal to this Court

was filed in the District Court on October 25, 1961 (R, 79).

Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to review this decision

by direct appeal is conferred by 28 U. S. C. §1253.

The following cases sustain this Court’s jurisdiction on

direct appeal: Florida Lime and Avocado Growers v. Jacob

sen, 362 U. S. 73; Kessler v. Department of Public Safety,

369 U. S. 153.

Statute Involved

La. R. S. §18:1174.1 enacted as Act No. 538 of the 1960

Regular Session of the Louisiana Legislature. It is printed

in volume 2 of the Louisiana Revised Statutes, 1960 Sup

plement, p. 385. The statute provides as follows:

3

Designation of race of candidates on paper and bal

lots—A. Every application for or notification or dec

laration of candidacy, and every certificate of nomina

tion and every nomination paper filed in any state or

local primary, general or special election for any elec

tive office in this state shall show for each candidate

named therein whether such candidate is of the Cau

casian race, the Negro race or other specified race.

B. Chairman of party committees, party executive

committees, presidents of boards of supervisors of

election or any person or persons required by law to

certify to the Secretary of State the names of candi

dates to be placed on the ballots shall cause to be

shown in such certification whether each candidate

named therein is of the Caucasian race, Negro race

or other specified race, which information shall be ob

tained from the applications for or notifications or dec

larations of candidacy or from the certificates of nomi

nation or nomination papers, as the case may be.

C. On the ballots to be used in any state or local

primary, general or special election the Secretary of

State shall cause to be printed within parentheses ()

beside the name of each candidate, the race of the

candidate, whether Caucasian, Negro, or other specified

race, which information shall be obtained from the

documents described in Sub-section A or B of this

Section. The racial designation on the ballots shall be

in print of the same size as the print in the names of

the candidates on the ballots.

Question Presented

Whether La. R. S. §18:1174.1 (Act No. 538 of the 1960

Regular Session of the Louisiana Legislature) which pro

vides for the designation of the race of candidates for elec-

4

tive office on nomination papers and ballots in all primary,

general or special elections violates the equal protection

and due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment,

and the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

Statement of the Case

Appellants, Negro citizens of the United States and the

State of Louisiana, and residents of the Parish of East

Baton Rouge, Louisiana, were candidates for nomination

to the office of School Board member of the Parish of East

Baton Rouge in the Democratic Party primary election

held on July 28, 1962. They filed a complaint in the Dis

trict Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana on June

8,1962 to enjoin the enforcement of Act No. 538 of the 1960

Regular Session of the Louisiana Legislature, naming as

defendant the Secretary of State of the State of Louisiana

who, by the terms of the statute, was charged with its en

forcement (R. 1). Asserting that the statute violated the

First, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Con

stitution of the United States, plaintiffs prayed for pre

liminary and permanent injunctions and a temporary

restraining order. They also asked that a three-judge court

be convened pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §§2281, 2284.

On June 11, 1962 the Motion for Temporary Restraining

Order was denied by District Judge West, and thereafter

a three-judge court was convened (R. 13; 18).

The cause was heard on June 26, 1962 before the three-

judge court. At the hearing an Answer was filed admitting

many facts alleged in the complaint (R. 31). Defendant

also moved to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction (R. 28). The

court recessed to consider its jurisdiction and having con

cluded that the case was properly before it reconvened to

hear the merits (R. 54).

5

In open court the parties stipulated that the defendant

was a ministerial officer required to follow R. S. §18:1174.1

and that he caused the ballots to be printed in accordance

with the provisions of the statute (R. 76-77). After argu

ment, the motion for preliminary injunction was denied by

the court on June 26, 1962 with Judge Wisdom dissenting

(R. 25). Thereafter, on June 29, 1962 the majority and

dissenting opinions were filed.

On September 19,1962 District Judge West denied plain

tiffs’ Motion for Leave to File a proposed Amended or

Supplemental Complaint, which alleged that the aforemen

tioned primary election was held on July 28, 1962 and that

in accordance with the statute in issue the race of appellant

was noted beside their names on the ballot (R. 66); that

appellant Anderson was defeated in the primary and appel

lant Belton was defeated in a subsequent run-off election

held September 1, 1962 (R. 66); that appellants’ unsuc

cessful candidacies were substantially influenced by the

operation and enforcement of the statute (R. 66); that

appellants “intend to be candidates in the next duly con

stituted democratic primary election for nomination as

members of the East Baton Rouge Parish School Board

and further that they intend to seek other public office” in

the parish and state in the future (R. 66).

On September 28, 1962, the District Court signed, and

on October 3,1962, entered a final order denying the prayer

for permanent injunctive relief (R. 70). This order incor

porated by reference the opinion of June 29,1962, and again

Judge Wisdom noted his dissent.

Notice of Appeal was filed in the District Court on Octo

ber 25, 1962 (R. 79).

6

The Question Presented Is Substantial

La. E. S. §18:1174.1 requires all candidates for elective

office in every election in Louisiana to state on every ap

plication for or notification or declaration of candidacy

whether they are “of the Caucasian race, the Negro race,

or other specified race.” It requires the Secretary of State

to print the racial description so obtained in parentheses

beside the name of every candidate on the ballots used “in

any state or local, primary, general or special election.”

Plaintiffs, both candidates for office in a primary election

as well as being qualified voters, sued to enjoin the Secre

tary of State from enforcing this law by making the re

quired racial designation on the ballot.

The majority of the court below, District Judges West

and Ellis, held the statute valid and enforceable as not

repugnant to the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments

to the Constitution of the United States. The majority

opinion by Judge West undertakes to distinguish the Louisi

ana statute in suit from a similar Oklahoma law which was

held unconstitutional in McDonald v. Key, 224 F. 2d 608

(10th Cir. 1955), cert, denied 350 U. S. 895.1

The opinion below held that while the Oklahoma law

required that the race of candidates be designated on bal

lots only if they were “other than of the white race” and

thus treated Negroes differently from other candidates,

the Louisiana statute was sufficiently different to be valid

since it required that candidates of all races be so desig

nated on the ballot. The majority also held that a candi

date has no right not to have his race disclosed and that

the court was “not disposed to create a shield against the

1 This opinion reversed a District Court opinion upholding

the Oklahoma statute at 125 F. Supp. 775 (W. D. Okla. 1954).

7

brightest light of public examination of candidates for pub

lic office” (R, 57).

Circuit Judge Wisdom adopted a contrary view and

agreed with appellants’ contention that McDonald v. Key,

supra, could not be distinguished in principle. As he ob

served, and as petitioners submit is altogether obvious,

“the omission of any racial designation on . . . [an Okla

homa] ballot amounted to the candidate identifying him

self as a white man just as surely as a Negro candidate

would identify himself by the word ‘Negro’ after his name.

The result was essentially the same result intended to be

accomplished by the Louisiana statute” (R. 51).2

Indeed, the trial court in McDonald v. Key, 125 F. Supp.

775, 777 (W. D. Okla. 1954), relied on this asserted equality

in treatment in upholding the Oklahoma statute using rea

soning very similar to that of the court below in the pres

ent case. The Oklahoma District Court said that placing

the word “Negro” on the ballot was “merely descriptive

and properly serves to inform the electors of the fact that

the candidate is of African descent,” and added that it

“likewise serves to inform the voters that the other candi

dates are members of the ‘white race’ ” (Id. at 777).

While the Tenth Circuit’s decision in McDonald v. Key

found a denial in equal treatment with respect to Negroes

who run for office in that their race was placed on the

ballot while the race of other candidates was not (224 F.

2d at 610), it is submitted that the opinion below conflicts

in principle with the decision in McDonald v. Key, supra,

and that this conflict between a Court of Appeals and a

statutory three-judge District Court demonstrates that the

question involved here is substantial.

2 Under the Oklahoma Constitution the “white race” included

all persons except Negroes. See McDonald v. Key, 224 F. 2d 608,

609 (10th Cir. 1955).

8

It is submitted that Judge Wisdom’s dissent in this case

effectively states the appropriate constitutional principles

which should decide the issue and demonstrates that the

result reached in McDonald v. Key, supra, is the correct

one.

The Louisiana law’s requirement that a candidate state

his race in order to gain a place on the ballot and that the

Secretary of State print each candidate’s race in paren

theses beside his name on the ballot infringes the liberty

of citizens and introduces a racial classification into the

electoral process while serving no legitimate end of the

State. Neither the State nor the court below has asserted

any legitimate governmental purpose to be served by the

required disclosure and designation. To be sure, it is said

that this designation informs the electorate, but no one has

said what state objective this accomplishes. A state might

rationally require that a candidate disclose and that the

voters be told of his qualifications for office, or indeed,

perhaps, even of his views on issues relating to the office

sought. But, racial designations have no rational relation

ship to candidates’ qualifications and the State has no

business placing its power and prestige behind a system of

racial identification of citizens. Electors may often cast

their ballots on the basis of the candidate’s race, religion,

national origin, or other factors not related to his qualifica

tions for office, but it is no legitimate object of the state

to feed or stimulate such prejudices in the elections it

conducts.

Indeed, racial classifications so rarely have any rational

connection with any legitimate objects of government as

to be “immediately suspect” necessitating “the most rigid

scrutiny.” Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 216.

“Distinctions between citizens solely because of their an

cestry are by their very nature odious to a free people

9

whose institutions are founded upon the doctrine of equal

ity.” Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100.

Beyond the absence of any valid state purpose in compel

ling candidates to declare their race and in putting a racial

stamp on them, thus requiring them to run for office as

Negroes or as whites, this statute must be viewed in the

context of Louisiana’s well-known policy of racial discrimi

nation against Negroes. This Court’s attention has been

repeatedly drawn to various manifestations of Louisiana’s

officially declared policy of racial separation all designed

to brand Negroes as inferiors to be set apart from whites

by the State.3

Having legally branded Negroes as an inferior race

by a host of laws and practices applied throughout com

munity life, Louisiana now, by R. S. §18:1174.1 insures

that the public will identify as such any individual member

of the state-designated “inferior race” who seeks public

office. In the context of this state policy, it is plainly no

answer to say that Caucasians are also required to make

similar self-identifications and to be racially designated on

the ballots. To be labelled as a member of the dominant

majority racial group is quite a different thing than to

be labelled as a member of a legally disadvantaged minority

race. As Judge Wisdom wrote in Hall v. St. Helena Parish

School Board, 197 F. Supp. 649, 655 (E. D. La. 1961), aff’d

368 U. S. 515:

To speak of this law as operating equally is to equate

equal protection with the equality Anatole France

spoke of: “The law in its majestic equality, forbids the

rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg

in the streets, and to steal bread.”

3 See the discussion of Louisiana’s policy in Mr. Justice Douglas’s

concurring opinion in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 181.

10

This Court rejected a parallel argument saying that “equal

protection of the laws is not achieved through indiscrimi

nate imposition of inequalities.” Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1, 22.

The majority of the Court that decided Plessy v. Fergu

son, 163 U. S. 537, 551, subscribed to the view that segre

gation laws, such as the Louisiana railroad segregation

laws and the similar laws that remain in that State, did

not stamp Negroes as inferior, but rather, that it was Ne

groes themselves who placed that construction upon them.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, rejected this

notion holding that segregation laws did, indeed, have

their intended result, namely, to disadvantage Negroes, the

racial minority set apart by the State. The Brown case

vindicated the first Justice Harlan’s dissent in Plessy,

supra at 554, where he wrote:

In respect of civil rights, common to all citizens, the

Constitution of the United States does not, I think,

permit any public authority to know the race of those

entitled to be protected in the enjoyment of such

rights . . . But I deny that any legislative body or ju

dicial tribunal may have regard to the race of citizens

when the civil rights of those citizens are involved.

Mr. Justice Harlan further expounded his view that the

post-Civil War amendments to the Constitution “removed

the race line from our governmental systems” (Id. at 555),

stating in often quoted language that:

But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law,

there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling

class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Consti

tution is color-blind and neither knows nor tolerates

classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all

citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the

peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as

11

man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of

his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the

supreme law of the land are involved (at 559).

As Judge Wisdom’s opinion indicated, racial classifica

tions are particularly inappropriate in the electoral process.

“If there is one area above all others where the Constitu

tion is color-blind, it is the area of state action with respect

to the ballot and the voting booth” (206 F. Supp. at 705).

Cf. Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 541. The purpose of

the Fifteenth Amendment to “forbid all discriminations

between white citizens and citizens of color in respect to

their right to vote” (United States v. Reese, 92 IT. S. 214,

226) and to proscribe denials or abridgements of the right

on the basis of race is patent.

Although this particular Louisiana law does not operate

directly to disfranchise Negroes or affect their entitlement

to vote and participate in the system of self-government, it

does affect their votes by injecting racism into the electoral

process in a manner calculated to stimulate the same racial

animosities otherwise encouraged by Louisiana’s segrega

tion laws. Louisiana thus encourages racial discrimination

by voters. Such an indirect effort to limit Negro participa

tion in government accomplishes the same objective as an

abridgement or denial of the franchise on the basis of race.

That this result will flow from the racially motivated

choices of voters does not make it any less repugnant to

the Constitution since governmental action under R. S.

18:1174.1 initiates the chain of events resulting in the dis

crimination, and this interplay of governmental and pri

vate action makes it more likely to occur. Cf. N. A. A. C. P.

v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 463.

Finafiy, the fact that this statute might operate to ben

efit a Negro candidate and against a white candidate in a

community, unlike East Baton Rouge where plaintiffs re-

12

side, which had a Negro electoral majority, is not relevant.

For, it is submitted that the State has a duty under the

Fifteenth Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment to

be “color-blind” and not to act so as to encourage racial

discrimination in the electoral process against any racial

group.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully prayed that the Court should review

the judgment of the District Court and enter a judgment

reversing the decision below.

Respectfully submitted,

M ichael M eltsner

N orman C. A maker

Of Counsel

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

J o h n n ie A. J ones

530 South 13th Street

Baton Rouge 2, Louisiana

M u rph y W. B ell

B ruce A. B ell

L eonard P. A very

S amuel D ickens

W ilm on L. R ichardson

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

U nited S tates D istrict Court

D istrict of L ouisiana

Civ. A. No. 2623

June 29, 1962

D upuy H. A nderson and A cie J. B elton ,

v.

Complainants,

W ade 0 . M artin , J r.,

Defendant.

Opinion

Before W isdom, Circuit Judge, and W est and E llis ,

District Judges.

W est, District Judge.

In 1960 the Louisiana Legislature enacted legislation

requiring the Secretary of State to place a racial designa

tion over the name of every candidate on the ballot in

the primary or general election.1 Under the statute the

1 LSA-R.S. Sec. 18:1174.1, Act 538 of 1960.

“Sec. 1174.1 Designation of race of candidates on paper

and ballots—A. Every application for or notification or dec

laration of candidacy, and every certificate of nomination and

every nomination paper filed in any state or local primary,

general or special election for any elective office in this state

shall show for each candidate named therein whether such

candidate is of the Caucasian race, the Negro race or other

specified race.

“B. Chairmen of party committees, party executive com

mittees, presidents of boards of supervisors of election or any

14

candidate must place his name and racial designation on

his certificate of candidacy and the Secretary of State uses

that information in preparing the ballot. The designation

applies to all candidates. The Statute requires that the

designation of “Caucasian”, “Negro”, or “other specified

race” be placed on the ballot after the name of each can

didate.

Plaintiffs are two Negro candidates for the school board

in East Baton Rouge Parish, State of Louisiana. They

challenge the constitutionality of this statute under the

First, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution and request injunctive relief against

the Secretary of State prior to the July 28, 1962, Demo

cratic primary.

The District Judge denied a temporary restraining order

and thereafter a three-judge court was convened pursuant

to 28 U. S. C. A. § 2284. Defendant filed his answer together

with a motion to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction in court on

the day of the hearing. The court recessed to consider its

jurisdiction and having concluded that it had jurisdiction,2

the court reconvened to hear the merits. The parties

person or persons required by law to certify to the Secretary

of State the names of candidates to be placed on the ballots

shall cause to be shown in such certification whether each

candidate named therein is of the Caucasian race, Negro race

or other specified race, which information shall be obtained

from the applications for or notifications or declarations of

candidacy or from the certificates of nomination or nomination

papers, as the case may be.

“C. On the ballots to be used in any state or local primary,

general or special election the Secretary of State shall cause

to be printed within parentheses () beside the name of each

candidate, the race of the candidate, whether Caucasian,

Negro, or other specified race, which information shall be

obtained from the documents described in Subsection A or B

of this Section. The racial designation on the ballots shall

be in print of the same size as the print in the names of the

candidates on the ballots.”

2 Jurisdiction is properly invoked under 28 U. S. C. A. §§ 1331,

1343(3), and 42 U. S. C. A. §§ 1971(a), 1981, 1983.

15

stipulated that the facts were as stated in plaintiffs’ com

plaint ; the case proceeded to argument, and was submitted.

At the outset it is important to grasp the fundamental

relationships of the parties. Plaintiffs are candidates for

office and the rights they advance arise out of that status.

Secondly, the statute in question is a state statute and

applies to all. While it requires the Negro to have his race

disclosed on the ballot, it requires the same of the Cau

casian, Mongolian, and so on. The garden variety dis

crimination between white and Negro is not involved.

Moreover, the state adopts no “sophisticated” method of

discrimination that might give us pause.3 The sole question

is whether the constitutional rights of a Negro candidate

are abridged when his race, like that of all other candidates,

is disclosed on the ballot pursuant to state statute.

Precisely which constitutional rights plaintiffs advance is

somewhat difficult to determine. Certainly the Fifteenth

Amendment gives plaintiffs no comfort. While the Four

teenth Amendment apparently protects rights broader than

those originally conceived by its drafters due to the Equal

Protection and Due Process clauses,4 the Fifteenth Amend

ment is direct in its protection.5 It is exclusively the right

to vote, and nothing more, which, in terms, is protected.

Surely the statute must be interpreted in such a way as to

protect the fundamental power of the franchise in whatever

context a State bent on discrimination seeks to cast it.6 But

3 See Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 59 S. Ct. 872, 83 L. Ed. 1281.

4 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 II. S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98

L. Ed. 873; Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, 74 S. Ct. 693, 98 L.

Ed. 884.

5 U. S. Constitution Amend., XV.

“Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote

shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State

on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

6 Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461, 73 S. Ct. 809, 97 L. Ed. 1152;

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299, 61 S. Ct. 1031, 85 L. Ed.

1368.

16

at no time has the Supreme Court expanded the protection

of the amendment beyond the franchise. Even with the

recognition that the Fifteenth Amendment created affirma

tive rights,7 the court has not gone beyond the protection

of the voter per se. Likewise, McDonald v. Key,s which is

urged on us as controlling, recognized that the right to

vote is not involved in a statute requiring racial designa

tions on the ballot. Moreover the facts of the case do not

suggest a restriction on voting rights. The unfathomable

vagaries of the voter operate just as freely with this statute

as without it. This statute merely contributes to a more

informed electorate. In any event, plaintiffs do not validly

assert a right under the Fifteenth Amendment.

[1] There is a creeping tendency, when dealing with

problems in the area of the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments,9 to outlaw State statutes on the grounds of their

lack of rightness or wisdom, while under the misapprehen

sion that only their constitutionality is being tested. This

the Supreme Court has told us, more than once, we may

not do.10 With due respect for our federalism, the court

must examine the Constitution and the various lines of

7 Ex parte Yarborough, 110 U. S. 651, 4 S. Ct. 152, 28 L. Ed.

274; Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347, 35 S. Ct. 926, 59 L.

Ed. 1340.

8 224 P. 2d 608 (10 Cir. 1955).

9 So that the matter may not confuse the issue let it be noted

that the First Amendment is wholly inapplicable to this ease deal

ing as it does with the powers of Congress. It is the rights

enumerated in the First Amendment which are included within the

Fourteenth Amendment upon which plaintiff relies. Gitlow v. New

York, 268 U. S. 652, 45 S. Ct. 625, 69 L. Ed. 1138.

10 Carpenters and Joiners Union, etc. v. Bitter’s Cafe, 315 U. S.

722, 62 S. Ct. 807, 86 L. Ed. 1143; Giboney v. Empire Storage <&

Ice Co., 336 U. S. 490, 69 S. Ct. 684, 93 L. Ed. 834; International

Brotherhood of Teamsters, etc., Union v. Hanke, 339 U. S. 470, 70

S. Ct. 773, 94 L. Ed. 995; Building Service Employees, etc. v.

Gazzam, 339 U. S. 532, 70 S. Ct. 784, 94 L. Ed. 1045.

17

Supreme Court decisions and determine if the State action

contravenes the Constitution. The examination must be

liberal so as not to exalt form over substance; it must be

circumspect so as to accord the states their just powers.11

[2] Plaintiffs’ reliance on the Fourteenth Amendment

suggests two lines of Supreme Court cases which might

control this action. The first of these is the right to ano

nymity defined in N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449,

78 S. Ct. 1163, 2 L. Ed. 2d 1488. This case, plus Bates v.

Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516, 80 S. Ct. 412, 4 L. Ed. 2d 480,

and Talley v. California, 362 TJ. S. 60, 80 S. Ct. 536, 4 L.

Ed. 2d 559, expounded the proposition that a person exercis

ing freedom of speech or association had a right to ano

nymity if disclosure entailed “the likelihood of a substantial

restraint upon the exercise * # * of their right to freedom

of association.” 12 Justice Black in Talley v. California,

supra at 65, 80 S. Ct. at 539, explained that “the reason

for these holdings was that identification and fear of

reprisal might deter perfectly peaceful discussions of public

matters of importance.”

It may be assumed, for present purposes, that plaintiffs

have a constitutional right to seek office.13 However, no

matter what the length and breadth of that right, there is

no basis for saying that a candidate for office has a right

to anonymity. The Court in N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, was

of the opinion that the injury to a right subsequent to

11 “To maintain the balance of our federal system, insofar as it

is committed to our care, demands at once zealous regard for the

guarantees of the Bill of Rights and due recognition of the powers

belonging to the states. Such an adjustment requires austere judg

ment, and a precise summary of the result may help to avoid

misconstruction.” Milk Wagon Drivers, etc. v. Meadowmoor, 312

U. S. 287, 297, 61 S. Ct. 552, 85 L. Ed. 836.

12 N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, supra, 357 U. S. at 462, 78 S. Ct.

at 1172.

13 See McDonald v. Key, 10 Cir., 224 F. 2d 608.

18

disclosure of identity precludes the right to identification.

A political candidate does not lose his right to run for

office by disclosure of his race. Further, it is safe to say

that his race, like his name and political affiliation which

also appear on the ballot,14 will come out in the campaign.

This court is not disposed to create a shield against the

brightest light of public examination of candidates for

public office.

The Court in Bates, N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, and Talley,

recognized that the right to anonymity could be abridged

in certain instances. However, in those instances, the State

bore the burden of showing an overriding interest in the

public sufficient to justify the partial abridgement of the

right.15 In the case before us the right of anonymity on

the ballot does not exist so far as this court can determine.

Thus this court is not put to any balancing since no per

sonal interests are placed in the scale opposite the State

interest, whatever it may be. We conclude that the

Louisiana statute does not violate the Fourteenth Amend

ment on that score.

The second line of cases which appears applicable are the

“state action” cases having their matrix in Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 68 S. Ct. 836, 92 L. Ed. 1161, and

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249, 73 S. Ct. 1031, 97 L. Ed.

1586. It is insufficient to state that these cases are dis

tinguishable because state action is clear in this case. These

cases must be read for their meaning as well as their facts.

The first case is, of course, McDonald v. Key, supra.

While it does not fall precisely within the “state action”

concept, it is the case closest on its facts and involves the

14 LSA-R. S. 18:671.

16 See also International Brotherhood of Teamsters, etc., Union

v. Hanke, 339 U. S. 470, 474, 70 S. Ct. 773, 94 L. Ed. 995; Inter

national Brotherhood of Teamsters, etc. v. Vogt, Inc., 354 U. S. 284,

77 S. Ct. 1166, 1 L. Ed. 2d 1347.

19

equal protection clause. There the Tenth Circuit found that

the requirement that only Negroes have their race desig

nated on the ballot violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

Plaintiffs attempt to make more of this case than is in it.

The Tenth Circuit did not require any intricate theory of

constithtional deprivation to strike down the Oklahoma

Statute. Negro candidates were treated different from all

other candidates without good reason being shown. Given

those facts the Court need not have gone further, and it

did not. This is not the case before us. Here all candidates

must state their race and have it printed on the ballot.

Plaintiffs must look further to find unconstitutionality.

Plaintiffs would have us find in Shelley v. Kraemer and

its progeny some principle which would deter a state from

placing racial classifications on the ballot. A brief synopsis

of the principle of these cases is in order. The Supreme

Court, in the first instance, recognized that discrimination

by private individuals was beyond the scope of the Four

teenth Amendment under the Civil Rights Cases.16 To this

was added the undeniable proposition that discrimination

by the states was improper under the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Further the Court held that ostensibly private dis

crimination which was in fact enforced by the state was

discriminatory “state action” under the Fourteenth Amend

ment.17 The crucial fact in all these cases, insofar as the

instant case is concerned, is that there existed a prior act

of actually proven discrimination to which the state was

privy. Either the private individual was seeking to exclude

Negroes from a neighborhood,18 or denying Negroes the

16109 U. S. 3, 3 S. Ct. 18, 27 L. Ed. 835. See Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U. S. 1, 13, 68 S. Ct. 836, 92 L. Ed. 1161.

17 Shelley v. Kraemer, supra; Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249,

73 S. Ct. 1031, 97 L. Ed. 1586; Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461, 73

S. Ct. 809, 97 L. Ed. 1152; Burton v. Wilmington Parking Author

ity, 365 U. S. 715, 81 S. Ct. 856, 6 L. Ed. 2d 45.

18 Shelley v. Kraemer, supra; Barrows v. Jackson, supra.

20

right to vote,19 or segregating buses,20 train terminals,21

restaurants,22 or golf courses.23 In those cases the state

sought either to enforce the discrimination24 or permit it

within the public domain.23 Since the Louisiana statute

does not discriminate on its face, the Court must ask where

the proven discrimination lies. Plaintiffs offer no proof

of actual discrimination against them.26 They ask the court

to take notice that discrimination among the electorate will

somehow occur as a result of this statute.27 Precisely how

this discrimination against plaintiffs can be discovered is

not made clear, much less how the state controls the dis

crimination through this statute. Nothing that we can find

in the state action cases suggest that a court may take a

state statute, and gaze into the future, seeking some gos

samer possibility of discrimination in a group of individuals

wholly beyond the control of the state. The discrimination

is Terry v. Adams, supra.

20 Boman v. Birmingham Transit Company, 5 Cir., 280 F. 2d 531.

21 Baldwin v. Morgan, 5 Cir., 287 F. 2d 750.

22 Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, supra.

23 Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 5 Cir., 304 F. 2d 320.

24 Shelley v. Kraemer, supra; Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co.,

supra.

25 Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, supra.

26 A classification in a statute having some reasonable basis does

not offend against the equal protection clause of the Constitution

even though in practice results in some inequality. One who assails

the classification in such a law must carry the burden of showing

that it does not rest upon any reasonable basis, but is essentially

arbitrary. Morey v. Bond, 354 U. S. 457, 77 S. Ct. 1344, 1 L. Ed.

2d 1485.

27 Plaintiff’s reliance on Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board,

E. D. La., 197 F. Supp. 649, is unavailing since in that case the

court was able to determine purpose from concrete results, or at

the very least easily predictable consequences. Plaintiffs do not

refer this court to any resulting discrimination and do not even

hint at predictable results.

21

must be real and the state must effect it. On this record

we find a nondiseriminatory statute and nothing more.

Judicial notice of a state policy of segregation avails us

nothing unless actual discrimination is proven as a result of

that policy through the medium of this statute. We have

previously found that the state treats all candidates alike.

For the foregoing reasons we conclude that the statute is

not in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, and the re

quest for preliminary injunction is denied.

W isdom, Circuit Judge (dissenting).

In the eyes of the Constitution, a man is a man. He is

not a white man. He is not an Indian. He is not a Negro.

If private persons identify a candidate for public office

as a Negro, they have a right to do so. But it is no part of

the business of the State to put a racial stamp on the ballot.

It is too close to a religious stamp. It has no reasonable

relation to the electoral processes.

When courts have struck down statutes and ordinances

requiring separate seating arrangements in buses, separate

restrooms, and separate restaurants in state-owned or

operated airports and bus terminals, it was not because the

evidence showed that negroes were restricted to uncom

fortable seats in buses, dirty restrooms, and poor food. It

was because they sat in buses behind a sign marked “col

ored”, entered restrooms under the sign “colored”, and

could be served food only in restaurants for “colored”. It

is the stamp of classification by race that makes the clas

sification invidious.

On principle, the case before us cannot be distinguished

from McDonald v. Key, 10 Cir., 1955, 224 F. 2d 608, cert,

den’d, 350 U. S. 895, 76 S. Ct. 153, 100 L. Ed. 787. In that

case the court had before it an Oklahoma statute requiring

that any “candidate who is other than of the White race,

shall have his race designated upon the ballots in paren-

22

thesis after Ms name.” Under the Oklahoma constitution,

the phrase “white race” includes not only members of that

race, but members of all other races except the Negro race.

The court held that this resulted in a denial of equality of

treatment with respect to Negroes who run for office. As

a practical matter, in Oklahoma the omission of any racial

designation on the ballot amounted to the candidate iden

tifying himself as a white man just as surely as a negro

candidate would identify himself by the word “negro” after

his name. The result was essentially the same result in

tended to be accomplished by the Louisiana statute. Act

538 of 1960 is somewhat more sophisticated in that there

is superficial appearance of equality of treatment. The

effect is the same in that candidates are classified by race,

and the State is using the elective processes to furnish in

formation and stimulus for racial discrimination in the

voting booth.

The State’s imprimatur on racial distinctions on the

ballot is no more valid than the State’s imprimatur on

separate voting booths. In Anderson v. Courson, 1962, 203

F. Supp. 806, 813, the District Court for the Middle District

of Georgia held that maintenance of racially segregated

voting places deprived Negroes of equal protection of the

law “in the matter of the exercise of the elective franchise,

a function and prerogative of utmost importance in the

process of government, and so intrinsically characteristic

of the dignity of citizenship”.

Considering the extent of media of information today, it

is highly unlikely that any voters will be confused by lack

of racial identification of candidates on the ballot. Con

sidering the number of parishes having a large Negro pop

ulation, it is entirely likely that a racial stamp will help

as much as it will hinder Negro candidates for public office

in Louisiana. The vice in the law is not dependent on in

jury to Negroes. The vice in the law is the State’s placing

23

its power and prestige behind a policy of racial classifica

tion inconsistent with the elective processes. Justice Harlan

put his finger on it many years ago when he said that the

“Constitution is color-blind”. If there is one area above

all others where the Constitution is color-blind, it is the

area of state action with respect to the ballot and the

voting booth.

I respectfully dissent.

24

U nited S tates D istrict Court

F or t h e E astern D istrict oe L ouisiana

B aton R ouge D ivision

Filed October 3, 1962

Civil Action No. 2623

D u pu y H. A nderson and A cie J. B elton ,

Complainants,

v.

W ade 0 . M artin , J r .,

Defendant.

Order

Plaintiffs’ motion for leave to file amended or supple

mental complaint has been denied.

The Court heretofore having fully heard the arguments

of counsel and having fully considered the evidence in

cluding stipulations of counsel, rendered judgment on June

26, 1962 denying plaintiffs’ request for a preliminary writ

of injunction. Its opinion in support of that judgment was

rendered on June 29, 1962 and is incorporated herein by

reference. The Court being of the opinion that for the rea

sons stated in its opinion, plaintiffs are not entitled to the

relief sought.

I t is ordered t h a t p l a i n t i f f s ’ p r a y e r f o r th e i s s u a n c e o f

a p e r m a n e n t i n ju n c t io n b e a n d th e s a m e i s h e r e b y d e n ie d .

Dated: Sept. 28,1962.

25

(Signed) E. Gordon W est

E. Gordon West

United States District Judge

(Signed) F rank B. E llis

Frank B. Ellis

United States District Judge

(Signed) J ohn M inor W isdom

John Minor Wisdom

United States Circuit Judge

Dissenting

Clerk’s Office

A True Copy

Oct 5 1962

(Signed) M ary A n n S anford

Deputy Clerk, United States District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

Baton Rouge, La.