Baskin v. Brown Brief and Appendix for Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Baskin v. Brown Brief and Appendix for Appellee, 1949. ab027ee1-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9630bf50-2950-466d-abd0-f53a2974c9f9/baskin-v-brown-brief-and-appendix-for-appellee. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

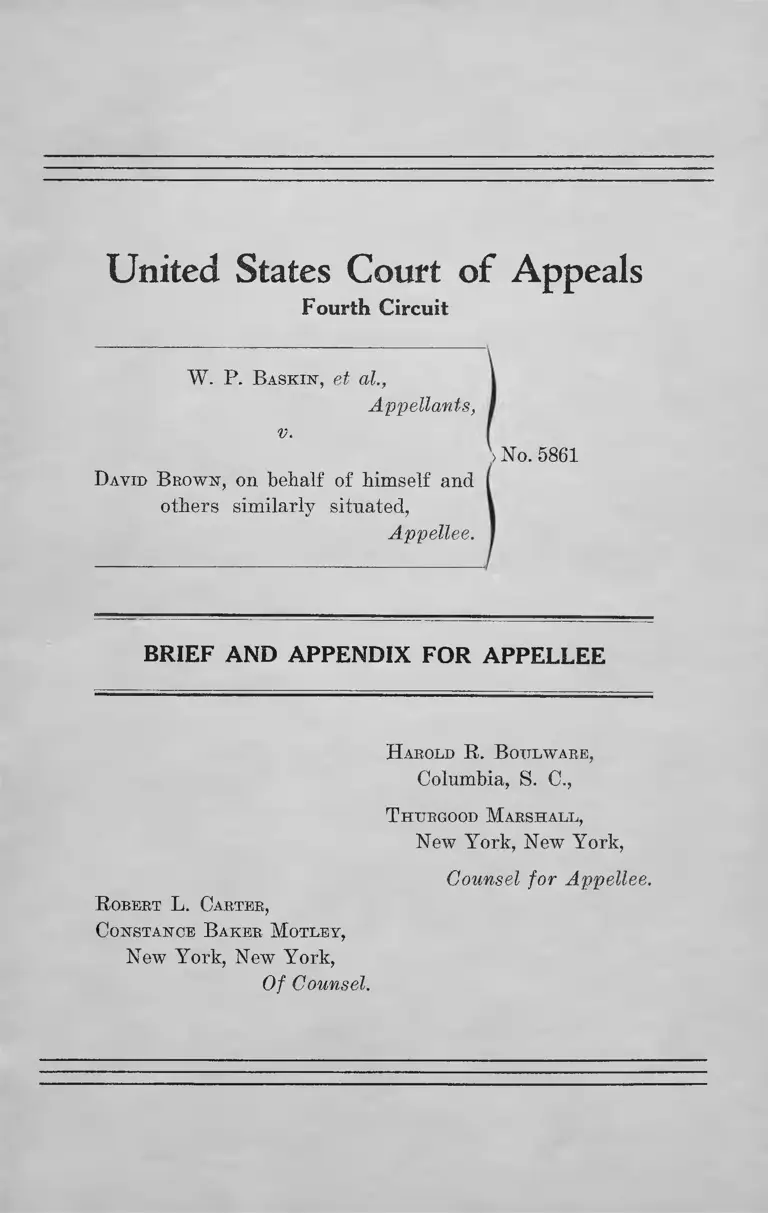

United States Court of Appeals

Fourth Circuit

W . P . B a s k in , et al.,

Appellants,

v.

D avid B row n , o n b e h a lf o f h im se lf a n d

o th e r s s im ila r ly s i tu a te d ,

Appellee.

>No. 5861

BRIEF A N D A PPEN D IX FOR APPELLEE

H arold R . B ottlware,

Columbia, S. C.,

T httrgood M arshall ,

New York, New York,

Counsel for Appellee.

R obert L. Carter ,

C onstance B aker M otley ,

New York, New York,

Of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of Case_______________ 1

Statement of Facts____________________________ 2

Argument:

Preliminary Statement ______________________ 2

I—The affidavit of John E. Stansfield was insuffi

cient on its face to require the trial judge to dis

qualify himself _________________________ 3

a. Statement Made in Dismissing Complaint As

to Three Defendants_______ 5

b. Statement Made After Hearing on Prelimi

nary Injunction _______________________ 6

c. Newspaper Reports of Statements Made at

Meeting _____________________________ 7

II—The actions of the Democratic Party of South

Carolina are subject to the prohibitions of the

United States Constitution to the same effect as

in the case of Rice v. Elmore_______________ 8

III—Rules 6, 7, and 36 of the Democratic Party of

South Carolina defy the prohibitions of the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Federal

Constitution ____________________________ 14

Conclusion ___________________________ 18

n

American Steel Barrel Co., Ex Parte, 230 IT. S. 35___ 4

Berger v. United States, 255 U. S. 25_____________ 4, 8

Bnchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 82________ :_____ 13

Cravens v. U. S., 22 F. (2d) 605 _________________ 4, 8

Cuddy v. Otis (C. C. A. 8), 33 F. (2d) 577__________ 8

Davis v. Schnell, 81 Fed. Supp. 872 (1949)________ 13,16

Elmore v. Rice, 72 Fed. Supp. 516, 165 F. (2d) 387,

cert, denied 333 U. S. 875 (1948)______________2, 3, 8

Fairbank, N. K. Co., Ex Parte, 194 F. 978 (1912) _____ 4

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 ______________ 16

Henry v. Speer, 201 Fed. 869 ___________________ 4

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400, 404__________________ 13

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Library, 149 F. (2d) 212___ ___ 13,15

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268___________________ 16

Lisman, In re (C. C. A. 2), 89 F. (2d) 898 __________ 8

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501_________________ 13,14

Minnesota & O. P. Co. v. Molyneaux (C. C. A. 8), 70 F.

(2d) 545 ____ __________ ____________ -______ ' 8

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 _______ -_1.__ 17

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 13

Ill

PAGE

Parker v. New England Oil Corp., 13 P. (2d) 497 —. 4,8

Sacramento S. F. T. Co. v. Tathom (C. C. A. 9), 40 F.

(2d) 894, cert, denied 282 TJ. S. 874 ____________ 8

Saunders v. Piggly Wiggly Corp., 1 F. (2d) 582 ....... 4

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1_________________ 13

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649_______________ 9,12

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. R., 323 U. S. 192__ 13,15

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303__________ 13

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, 332 U. S.

410 ______________________________________ 13

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33_____________________ 13

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, 323

U. S. 210 ________________________________ 13,15

Virginia Ex Parte, 100 U. S. 339_________________ 13

Virginia v. Reeves, 100 U. S. 313_________________ 13

Wilkes v. United States (C. C. A. 9), 80 F. (2d) 285 __ 8

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356.______ _________ 13

O ther A u th orities

Constitution of United States

Article I, Secs. 2 and 4, Amendments 14 and 15___ 1

United States Code

Title 8, Secs. 31 and 4 3 ______________________ 1

Title 28, Sec. 144 __ ________________________ 8

IV

Index to A p p en d ix

PAGE

I—Abstracts of Proceedings on Hearing for Pre

liminary Injunction ____________________ la.-5a

II—Testimony of W. P. Baskin on Hearing for Pre

liminary Injunction ___ ________________ 5a-28a

III—Testimony of David Brown on Hearing for Pre

liminary Injunction ___i____,___________ 28a-29a

United States Court of Appeals

Fourth C ircuit

W . P. B a s k in , et al.,

Appellants,

v.

D avid B row n , on b e h a lf o f h im se lf a n d

o th e r s s im ila r ly s i tu a te d ,

Appellee.

No. 5861

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

Statem ent of Case

On July 19, 1948, the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of South Carolina entered an order

herein which temporarily enjoined the defendants-appel-

lants from denying to plaintiff-appellee, and others simi

larly situated, the right to enroll in local Democratic party

clubs solely because of their race and color and from deny

ing to plaintiff-appellee, and others similarly situated, the

right to vote in the Democratic party primary of August

10, 1948 without first presenting general election certificates

not required of white voters and without first having taken

the oath prescribed by the Democratic party’s rules.

The basis for this temporary injunction was that the

acts complained of denied plaintiff-appellee rights guar

anteed by Article I, sections 2 and 4, of the Constitution of

the United States, and Amendments Fourteen and Fifteen

thereof and was in violation of rights protected by Title 8,

Sections 31 and 43.

o

On October 22, 1948, at a bearing held in the district

court, it was found that its order of July 19, 1948 had been

obeyed. Plaintiff amended his pleadings by striking out

his pleas for damages. The case was then heard on a

stipulation of facts by the parties, the testimony of wit

nesses and oral argument. On November 26, 1948 an order

permanently enjoining defendants-appellants from denying

plaintiff-appellee, and others similarly situated, the above

rights was entered by the court. The points raised by ap

pellants on this appeal have been adjudicated by the court

below and are set out as principle questions in appellants’

brief. Appellee’s reply to these questions is contained in

the argument in this brief.

Statem ent of Facts

The Statement of Facts set forth in appellants’ brief

is essentially correct. There are some errors and minor

inaccuracies which will be pointed out in the argument in

this brief. The material facts in this case are accurately

set forth in the Findings of Fact of the District Judge and

appear in Appendix for Appellants, pages 80 to 84.

A R G U M E N T

Preliminary Statem ent

The decision of the district court and this Court in the

case of Elmore v. Bice, were well known to the appellants

in this case. Senator W. P. Baskin was one of the attorneys

and was a witness in that case. The decisions in the Elmore

case were known to those who drafted the 1948 rules and

those who participated in adopting these rules because the

rules specifically cite the decison of Judge W aking . In view

of the fact that the appellants are all either members of the

3

State Committee or County Chairmen of the Democratic

Party of South Carolina they must have been familiar with

these decisions.

Although the decision in the Elmore case was technically

only against the officials of the Richland County group of

the Democratic Party, the precedent established in that case,

affirmed by this Court, and certiorari denied by the Supreme

Court, was entitled to be respected by all of the units of

the Democratic Party of the State of South Carolina.

It is clear, however, from the action of the appellants,

their testimony, their pleadings, and their brief in this

Court, that they refuse to recognize the validity of the de

cision of the trial court or the decision of this Court in the

case of Elmore v. Rice.

Appellants’ brief filed in this Court really consists of

only two points, (1 ) that Judge W aring should have dis

qualified himself pursuant to the Stansfield affidavit and;

(2) that the decision in Elmore v. Rice was wrongly decided

and should be overruled.

I

The affidavit of John E. Stansfield w as insufficient

on its face to require the trial judge to disqualify

him self.

The affidavit of appellant John E. Stansfield was filed

just prior to the final hearing in this case. The affidavit

includes quotations from statements made by the district

judge in dismissing the complaint as to certain of the defen

dants, statements made at the close of the hearing for a

preliminary injunction after testimony and argument, and

quotations from a newspaper article commenting upon a

speech of the district judge made before the National Law

yers Guild Chapter in New York City.

4

The affidavit and the brief for appellants filed in this

Court did not make it clear that the reference to the actions

of the officials of the Democratic Party of South Carolina

in relation to their refusal to follow the spirit of the Elmore

decision were made by the district judge after a full hear

ing on the preliminary injunction and after the appellants

had made no showing of any kind which could either factu

ally or legally support their actions. These comments were

made in the rulings of the District Judge on the motion

for preliminary injunction and neither the statements from

the bench nor the opinion filed on the motion for prelimi

nary injunction go beyond the recognized scope of judicial

opinion made after consideration of the evidence and argu

ments. Failure of appellants to produce testimony on their

behalf or to make legal arguments on their behalf cannot

be used as the basis for later charges of bias on the part of

the trial judge.

The decisions interpreting the old disqualification stat

ute are clear that there must be a showing of personal bias

against or in favor of one or more parties to the litigation.

Henry v. Speer, 201 Fed. 869; Cravens v. U. S., 22 F. (2d)

605; Ex parte N. K. Fairbank Co., 194 F. 978 (1912); Parker

v. New England Oil Corp., 13 F. (2d) 497; Ex parte Amer

ican Steel Barrel Co., 230 U. 8. 35; Saunders v. Piggly

Wiggly Corp., 1 F. (2d) 582; Berger v. United States, 255

U. S. 25. All of the decisions relied upon by the appellants

and other decisions not cited by them make it clear that the

affidavit must make an affirmance of personal bias. It is

likewise clear from the cases that comments of the trial

judge upon the law and/or the evidence are not within the

rule. A reading of the affidavit demonstrates clearly that

there is no showing of personal bias. United States Dis

trict Judge J. W aties W aring in refusing to disqualify him

self made the following comment upon the affidavit:

0

“ T h e Co u r t : There are two parts to it. The

first complains of my decision. Well, I am of the

opinion that the decision was right. It is in con*

formity with the opinions in other cases, which have

been affirmed. It is the plain law of the land, and

certainly it is the law in this case as this case hasn’t

been appealed from. The second one seems to be on

the ground that I spoke in New York at a Lawyers

meeting, which I did, based on some newspapers re

ports, which are mostly correct, and the address was

to the effect that I was in favor of enforcing the law.

I assume that if I had made a speech that I believed

in enforcing the law against murder, I would have to

disqualify myself from trying a murder case on this

theory. I suppose that if I had said I was in favor

of enforcing the revenue laws, I couldn’t try any of

the numerous illicit distilling violations. There is

nothing to the motion. Petition dismissed. Let us

proceed to the other motions in this case” (A68).

a. S ta tem en t M ade in D ism issing C om plaint A s to T hree

D efen d an ts.

In the Appendix filed with this brief, pages la-5a, there

appears the full statement as to the dismissing of the com

plaint as to certain of the defendants. These defendants

had filed motions setting forth in great detail sufficient

grounds for dismissal as to them. These defendants made

it clear that they did not intend to do any of the acts which

were the basis of the complaint in this case. They made it

clear that despite the rulings of the Democratic Party of

South Carolina they had refused to prevent qualified Negro

electors from enrolling or to enforce the oaths complained

of or to in any other manner discriminate against qualified

Negro electors. In dismissing the complaint as to these de

fendants the district judge stated: “ I thank you for your

returns, not personally, on behalf of the government—on

behalf of the American people. I ’m glad to see that some

6

of our citizens realize that this country is an American

country; that it is not a country of persecution; that it is

not a country of minorities or parties, groups or religious

creeds, races. I hope that the press will publish the whole

or excerpts of the returns made by these three counties,

and my brief remarks in regard to them” (A4a). Obvi

ously this statement does not demonstrate personal bias

against the appellants or in favor of the appellee herein.

b. S ta tem en t M ade A fter H earin g on P relim inary

Injunction .

The quotations in the affidavit as to the leaders of the

party is a reasonably accurate statement of the remarks of

the trial judge appearing in the transcript of testimony of

that hearing on pages 52-53. It should be made clear that

these statements were made at the close of the hearing for

a preliminary injunction. It was the conclusion of the trial

judge after the appellants had failed to put in any testimony

attempting to justify their action and after the attorneys

representing appellants had made it clear that they would

not make an argument as to the law involved, but rather

stated: “ We are going to submit, as far as the defendants

are concerned, without argument.”

It was clear from the testimony of appellant Baskin and

from the new rules of the Democratic Party of South Caro

lina that their action was a deliberate and determined ac

tion which was aimed at refusing to follow the precedent

in the Elmore decision. There could be no doubt that the

continuation of the practice of restricting enrollment to

“ white” Democrats was not only a violation of the spirit

of the Elmore decision but was in direct violation of the.

opinion of the district judge in the Elmore case. “ The

plaintiffs and others similarly situated are entitled to be

7

enrolled and to vote in the primaries conducted by the

Democratic Party of South Carolina.” 72 Fed. Supp. at

page 528. (Italics ours.)

This statement by the district judge is in keeping with

the recognized practice of commenting upon the evidence

or lack of evidence and other proof and the law involved in

the case. This most certainly cannot be construed as evi

dence of personal bias.

c. N ew sp ap er R eports o f S ta tem en ts M ade a t M eeting .

The remaining part of the Stansfield affidavit deals with

the newspaper report of a speech made by the district judge

after the hearing on the preliminary injunction. The speech

was made in New York City at a meeting of the New York

chapter of the National Lawyers Guild. In the first place,

there is nothing out of the ordinary in a United States

District Judge attending and speaking at meetings of a

recognized national bar association. As a matter of fact it

is a common practice and is necessary for the betterment of

the lawyers of our country.

The district judge stated that the newspaper clipping

was reasonably accurate and could only be interpreted as

his determination to enforce the Constitution and laws of

the United States in an impartial manner without regard

to race, creed or color. His statements cannot possibly be

interpreted as personal bias. Rather, it is clear that his

statements demonstrate an absence of bias.

In the affidavit, as well as the newspaper clipping there

appears to be emphasis on the fact that the district judge

made a comment that if one of the attorneys for the ap

pellee had not brought legal action, Negroes would not be

voting in primary elections in South Carolina. A study of

the decision in the Elmore case, along with the background

of disfranchisement of Negroes in South Carolina, plus the

determined efforts to flaunt the Constitution and laws of

the United States makes it clear that unless someone had

brought that type of legal action, Negroes would not now

be voting in South Carolina.

Other quotations in the newspaper article point to

Judge W ardstg’s comment as to the question of race rela

tions in the south. These comments could in no wise be

interpreted as expressions of personal bias against the

appellants.

Appellant Stansfield’s affidavit, then, is insufficient as a

matter of law as it fails to show that personal bias and

prejudice against affiant or any other defendant-appellant

or in favor of plaintiff-appellee required by Title 28 U. S. C.

144. Compare Berger v. United States, supra; with Parker

v. New England Oil Corp., supra; Craven v. United States,

supra; Cuddy v. Otis (C. C. A. 8), 33 F. (2d) 577; Sacra

mento, S. F. T. Co. v. Tatkom (C. C: A. 9), 40 F. (2d) 894,

Cert, denied 282 U. S. 874; Minnesota & 0. P. Co. v. Moly-

neaux (C. C. A. 8), 70 F. (2d) 545; Wilkes v. United States

(C. C. A. 9), 80 F. (2d) 285; In re Usman (C. C. A. 2), 89

F. (2d) 898.

II

The actions of the Dem ocratic Party of South Caro

lina are subject to the prohibitions of the U nited States

Constitution to the sam e effect as in the case of R ice

v. Elm ore.

This case is the sequel to the case of Elm,ore v. Bice, 72

F. Supp. 516 (1947), 165 F. (2d) 387, cert, denied 333 U. S.

875 (1948), which was before this Court on appeal from

the decision of the same court in this case almost one year

9

ago to the day. In that case the district court found that

immediately after the decision of the United States Su

preme Court in the case of Smith v. AllwrigM, 321 U. S. 649

(1944) the State of South Carolina in extra-ordinary session

called by the then Governor repealed every statutory pro

vision regulating the primary as well as the Constitutional

provision authorizing primary laws. Thereafter, the Demo

cratic Party boldly excluded Negroes (1) from membership

and (2) participation in its primary election solely because

of race and color.

The opinion of the district judge in the Elmore case,

supra, concluded that “ the prayer of the complaint for a

declaratory judgment will therefore be granted by which

it will be adjudged that the plaintiff and others similarly

situated are entitled to be enrolled and to vote in the pri

maries conducted by the Democratic Party of South Caro

lina” (72 Fed. Supp. 516, 528).

The basis for this conclusion was clearly stated as fol

lows :

“ I am of the opinion that the present Democratic

Party in South Carolina is acting for and on behalf

of the people of South Carolina; and that the Pri

mary held by it is the only practical place where one

can express a choice in selecting federal and other

officials. Racial distinctions cannot exist in the

machinery that selects the officers and lawmakers of

the United States; and all citizens of this State and

Country are entitled to cast a free and untrammelled

ballot in our elections, and if the only material and

realistic elections are clothed with the name ‘pri

mary’, they are equally entitled to vote there” (72

Fed. Supp! (2d) 516, 528).

The final judgment in the Elmore case was appealed to

this Court and the judgment of the District Court was

affirmed and in the opinion of this Court it was made clear

10

that race and color should not play any part whatsoever in

the election machinery of the State of South Carolina,

whether it be in the general election, primary election, or

any parts thereof:

“ The use of the Democratic primary in connec

tion with the general election in South Carolina pro

vides, as has been stated, a two step election ma

chinery for that state; and the denial to the Negro of

the right to participate in the primary denies him all

effective voice in the government of his country.

There can be no queston that such denial amounts to

a denial of the constitutional rights of the Negro;

and we think it equally clear that those who partici

pate in the denial are exercising state power to that

end, since the primary is used in connection with the

general election in the selection of state officers.

There can be no question, therefore, as to the juris

diction of the court to grant injunctive relief, whether

the suit be viewed as one under the general provision

of 28 U. S. C. A., section 41 (1) to protect rights

guaranteed by the Constitution, or under 28 U. S. C.

A., section 41 (11) to protect the right of citizens of

the United States to vote, or under 28 U. S. C. A.,

section 41 (14) to redress the deprivation of civil

rights” (165 Fed. (2d) 387, 392).

Although, prior to the Elmore decisions, it was possible

to argue that the constitutional guarantees relied upon by

the appellee were not applicable to the South Carolina

election set-up, it is now perfectly clear that the entire elec

tion machinery of South Carolina comes within the prohi

bition of our Constitution. However, the appellants as

state officials of the Democratic Party of South Carolina,

continuing their determination to use race and color as an

effective bar to the exercise of the right to make a meaning

ful choice of elected representatives, deliberately ignored

the true intent of the Elmore decisions and sought to ac-

11

complish the same purpose by other devious means. As

was pointed out in the Report of the President’s Committee

on Civil Rights:

“ This report cannot adequately describe the

history of Negro disfranchisement. At different

times, different methods have been employed. As

legal devices for disfranchising the Negro have been

held unconstitutional, new methods have been impro

vised to take their places. Intimidation and the

threat of intimidation have always loomed behind

these legal devices to make sure that the desired re

sult is achieved.” (“ To S ecure T h e se R ig h t s , ” pp.

35-36.)

No place in either the pleadings or the briefs in this

case have the defendants-appellants made a serious effort

to deny that the true purpose of their action is to exclude

Negroes solely because of race or color from participation

in the Democratic Party of South Carolina.

On May 19,1948, at the regular Convention of the Demo

cratic Party held in Columbia, South Carolina, rules were

adopted in place of the rules of the party previously in

force. Membership in the Democratic Party clubs con

tinued to be limited, among other things, to,

“ * * * a white Democrat who subscribes to the prin

ciples of the Democratic Party of South Carolina as

declared by the State Convention.”

Participation in the Democratic primary was limited by

these rules to

“ * * # all duly enrolled club members * * * if they

take the oath required of voters in the primary; and

in conformity with the order of Judge J. Waties

Waring, United States District Judge, in the case of

Elmore etc. v. Rice, et al., all qualified Negro elec

tors of the State of South Carolina are entitled to

12

vote in the precinct of their residence, if they present

their general election certificates and take the oath

required of voters in the primary.”

The oath required of voters was also provided for in

the rules and required, among other things, that,

“ I further solemnly swear that I believe in and

will support the principles of the Democratic party

of South Carolina, and that I (understand and) be

lieve in and will support the social (religious) and

educational separation of races.

“ I further solemnly swear that I believe in the

principles of the Democratic party of South Carolina,

and that I (understand and) believe in and will sup

port the social (religious) and educational separa

tion of races.”

The position of appellants in this case is made clear in

their brief. For example, they admit that the decision now

appealed from ‘ ‘ is virtually identical with a like holding in

Elmore v. Rice * * * which was affirmed by this Court * * * ” 1

The true purpose of the appeal in this case is set forth

by the appellants as follows: “ We respectfully urge on the

Court the view that the Democratic Party of South Caro

lina’s primaries are not state action subject to the Consti

tutional and statutory provisions relied on by appellee, and

that Rice v. Elmore, supra, should be modified accord

ingly. ’ ’2

Throughout the brief for appellants, the argument made

by the appellants in Rice v. Elmore is repeated. This argu

ment is based on the freedom of assembly provision of the

Constitution, the assertion that the only election provided

by statute in South Carolina is the general election; that

the decision in Smith v. Allwright is based solely on statu-

1 Appellant’s Brief page 38.

2 Appellant’s Brief page 45.

13

tory control of the primary machinery and that the portion

of the decision in U. S. v. Classic relied upon by this Court

in the Elmore case was in fact merely dicta. All of these

points were fully argued in the Elmore case.

The brief for appellants completely ignores not only the

effect of the decisions in regard to primaries of the type

here involved but also ignored the applicable decisions con

trolling so-called private action which in effect is perform

ing governmental functions such as Marsh v. Alabama, 326

U. S. 501; Steele v. Louisville da Nashville RR, 323 U. S.

192; Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, 323

U. S. 210; Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Library, 149 F. (2d) 212.

The United States Supreme Court has also made it clear

that racial distinctions cannot legally exist in governmental

functions in this country. Takahashi v. Fish & Game Com

mission, 332 U. S. 410, 420 L. ed. 1096, 1101; Oyama v. Cali

fornia, 332 IT. S. 633, 640, 646; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S.

1, 20, 23; Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 373, 374;

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 82; Hill v. Texas, 316

U. S. 400, 404; Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303,

307, 308; Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33, 41, 42; Virginia v.

Reeves, 100 U. S. 313, 322; Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339,

344, 345.

Although it might not yet be clear that all types of racial

distinctions are invalid, there is at least one area of Ameri

can law in which it has been made clear that race or color,

either expressed or implied, is invalid. That area is the

right of an American citizen to qualify for and participate

in the election of governmental officials. The most recent

instance of the application of this doctrine is in the case of

Davis v. Schnell, 81 Fed. Supp. 872 (1949) which was

affirmed by the United States Supreme Court on Monday,

March 28.* In that case, the Boswell Amendment to the

* October Term, 1948, No. 606.

14

Constitution of the State of Alabama was declared uncon

stitutional as effectively depriving Negroes of the right to

register although the amendment made no mention what

soever of race or color.

The legal status of the Democratic Party of South Caro

lina was determined in the Elmore ease. That decision' is

in keeping with earlier and later decisions of the United

States Supreme Court. It is admitted that the factual

basis of the Democratic Party in South Carolina in the

Elmore case is unchanged (A29a). The Democratic Party

of South Carolina is no more of a private organization to

day than it was at the time of the Elmore case.

I ll

Rules 6, 7, and 36 of the Dem ocratic Party of South

Carolina defy the prohibitions o f the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Am endm ents to the Federal Constitution.

Rule 6 which limits membership in the Democratic Party

of South Carolina to white Democrats is in clear violation

of the decisions in the Elmore case. The validity of such a

provision depends upon the theory of appellants that the

Democratic Party of South Carolina is a private organiza

tion outside the scope of the United States Constitution.

This theory is in conflict with the decisions in the Elmore

case and other relevant decisions.

In other cases, the Supreme Court has recognized that it

is not the symbols and trappings of officialdom which de

termine whether the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

apply but rather whether the facts of the particular case

disclose the exercise of the state’s authority. For example,

in Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, the Supreme Court held

that the Fourteenth Amendment operated on the private

owner of a “ company town” to protect the right of freedom

15

of speech. Labor unions, although private voluntary asso

ciations, have been held by the Supreme Court subject to the

limitations of the due process clause of the Constitution

when exercising powTer conferred by the federal govern

ment. Steele v. Louisville and Nashville RR, 323 U. S. 192,

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, 323 U. S.

210. Similarly this Court in Kerr Enoch Pratt Free

Library, 149 F. (2d) 212, certiorari denied, 326 U. S. 721,

held that where a corporation had invoked the power of

the state for its creation and relied upon city funds for its

operation it was in fact a state instrumentality.

The effect of Rule 6 is not only to deprive qualified Negro

electors of the right to participate in that portion of the

election machinery of the State of South Carolina controlled

by the Democratic Party but sets up a dual standard for

qualifying to vote in the Democratic primary elections. This

is apparent from Rule 7 which provides that enrolled club

members are entitled to vote without further qualifications

but that qualified Negro electors are required to “ present

their general election certificates” . This dual standard of

qualifying to vote based solely upon race or color is in clear

violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

Although Rule 36 did not mention race or color as such,

the purpose of that rule and the statement of party prin

ciples were likewise aimed at depriving Negroes of the right

to exercise their choice of elected representatives. This is

not only clear from the pleadings and the testimony of

Senator Baskin but is also clear from the brief for appel

lants. For example, in commenting upon these specific pro

visions and rules, the appellants stated: “ Under those pro

visions, the appellee and those for whom he sues [all quali

fied Negro electors] were not eligible to enroll as members

of the party or to vote in this primary, even after the elimi

nation of that portion of Rule 6 which limits membership

to white Democrats” (Appellant’s Brief, p. 37).

16

In the most recent decision pertinent to the instant case,

the United States Supreme Court affirmed the decision of

the United States District Court for the Southern District

of Alabama in the case of Davis v, Schnell, 81 Fed. Supp.

872 (1949), affirmed, United States Supreme Court, October

Term, 1948, No. 606. The opinion of the District Court

stated:

“ It, thus, clearly appears that this Amendment

was intended to be, and is being used for the purpose

of discriminating against applicants for the fran

chise on the basis of race or color. Therefore, we are

necessarily brought to the conclusion that this Amend

ment to the Constitution of Alabama, both in its ob

ject and the manner of its administration, is unconsti

tutional, because it violates the Fifteenth Amend

ment. While it is true that there is no mention of

race or color in the Boswell Amendment, this does

not save it. The Fifteenth Amendment ‘nullifies

sophisticated as well as simple-minded modes of

discrimination,’ and ‘It hits onerous procedural re

quirements which effectively handicap exercise of the

franchise by the colored race although the abstract

right to vote may remain unrestricted as to race.’

Lame v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 275, 59 8. Ct. 872, 876,

83 L. Ed. 1281. Cf. Smith v. Allwright, supra; Guinn

v. United States, supra."

The decision in the Boswell Amendment case declares

invalid the latest method in the long history of efforts to

prevent Negroes from qualifying to vote. See Guinn v.

United States, 238 U. S. 347, Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. 8. 268.

The method of preventing Negroes from participating

in the choice of elected officials in South Carolina is in the

same category as to efforts to continue the white primary

as was the Boswell Amendment effort to continue the policy

of preventing Negroes from qualifying to vote. Both in

genious methods were invented as a deliberate effort to

17

circumvent the Constitution and laws of the United States

as interpreted by the courts.

Rule 36 as adopted by the 'Democratic convention in

South Carolina is set forth in the Appendix on pages 83-84.

As originally adopted the oath contained the provision that

the person applying must swear that he understood and

believed in certain principles. The words ‘ ‘ understand and’ ’

were later deleted by the Executive Committee of the Demo

cratic Party. There is serious question as to whether or

not the Executive Committee had authority to do so. It is

not clear as to whether or not the words would have been

returned to the oath but for the preliminary injunction in

this case.

The oath required that a person applying to vote must

believe in the “ social and educational separation of the

races” and oppose “ the proposed federal so-called F. E.

P. C. law.” In the brief of appellants it is made clear

that the proposed oath was not only an indefinite and un

reasonable limitation on the right to vote but that it was

aimed at denying Negroes the right to vote. For example,

attorneys for the appellants set forth in their brief the

statutes which they claimed to be included in the phrase,

“ social and educational separation of the races.” Included

among these statutes is one requiring the segregation of

the races in transportation. Such a statute is invalid as

applied to interstate passengers since the decision of the

Supreme Court in the case of Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S.

373, so that it would be impossible for the average voter to

“ understand” the exact meaning of the phrase in the oath

he was required to make. However, the Negro applicant

while having some doubt as to the significance of the pro

visions themselves would have no doubt that he was being

required to swear to oppose fair employment practices

legislation aimed solely at preventing discrimination against

18

him in employment because of race and color. So, it is

clear that the intent of appellants as set forth in their brief,

quoted above, coincides with the actual effect of such a

provision.

Appellants contend that the decision of the Court below

interferes with their right peaceably to assemble and thus

contravenes the First Amendment to the Constitution. This

contention is as spurious as it is novel. The actual ‘4 right ’ ’

which appellants assert is the absolute authority to deprive

Negroes in South Carolina of the effective exercise of their

right to choose members of Congress. The record in this

case shows plainly that in conducting the primary election

in the State of South Carolina the Democratic Party is not

a group of individual citizens assembling peaceably to

secure redress for grievances. It is an organization carry

ing on a part of the function of the state government to

select representatives and senators to sit in the Congress

of the United States and it is to that activity to which the

Court below applied the Constitutional limitations. In any

event, appellants’ right to assemble cannot be so exercised

so to deprive appellee of his right to vote and this Court

so held in Bice v. Elmore, supra.

Conclusion.

W h er efo r e , it is respectfully submitted that the judg

ment of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of South Carolina should be in all respects affirmed.

H arold R . B oitlware,

Columbia, S. C.,

T hxjrgood M arshall ,

New York, New York,

Counsel for Appellee.

R obert L. Carter,

C onstance B aker M otley ,

New York, New York,

Of Counsel.

A ppendix.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT,

E astern D istrict of S o u th C arolina .

[ s a m e t i t l e ]

Charleston, S. C., July 16, 1948, 10 a. m.

[Tr. 1]

# = * # # # #

The Court: I have read the pleadings. The pleadings

have been served. Have plaintiff’s attorneys read the re

turns?

Mr. Marshall: We have read every return. We wish

to make a motion as to certain—

The Court: As to individual returns first you wish to

make a motion?

Mr. Marshall: Yes, sir.

The Court: I ’d like to hear it.

[Tr. 3]

Mr. Marshall: As to the return of C. Victor Pyle,

County Chairman of the Democratic Party of Greenville

County; as to the return of the defendant, James P. Sloan,

Laurens County, and, if your Honor please, as to particu

larly Laurens County, the affidavit was not attached, with

the understanding between us, and we have no objection, to

its being filed and it being considered.

The Court: That will be done, Mr. Price?

Mr. Price: Yes, sir.

The Court: Very good.

2a

Discussion

Mr. Marshall: The other one, the defendant, Julian I).

Wyatt, Chairman of the Democratic Party of Pickens

County.

As to these three defendants, if in order, we move that

the temporary injunction as to them be resolved and vacated

and they be dismissed from this action. The reason for this

is that we consider these returns to be full and complete.

As far as we can see, they answer each of the allegations in

the case.

As to the return of the defendant, Mr. Purdy, it does not

have any allegation at all concerning the oath. For that

reason we cannot move to dismiss concerning this. As to

the other three, we move, if in order—

The Court: Anything to say in regard to that, Mr.

Rivers!

Mr. Rivers: The position of Mr. Purdy is that he is not

interested in supporting the oath. His committee has not

[Tr. 4]

met, but, of course, whatever your Honor rules on that will

be followed by the executive committee—

The Court: Well, but the question here is that plaintiff

is moving for dismissal as to the three counties that have

completely conformed—like Richland, that is not a party to

the cause—and I ’m uncertain whether Mr. Purdy’s county

should be kept within the cause or also dismissed. Is Mr.

Purdy present?

Mr. Rivers: Mr. Purdy is present.

The Court: Does Mr. Purdy desire to amend his return

by saying that this oath or form of oath, whether in original

or amended form, that is prescribed by the state party will be

administered in the primary to be held on the second Tues-

3a

Discussion

day in August of this year, or whether people will be al

lowed to vote without taking that oath?

Mr. Purdy: I belong to the executive committee, and

we haven’t got that. We’ve been trying to cross bridges

as we came to them. I don’t think I would have the au

thority to say we would or wouldn’t. The only thing I

have authority to say is I know we are not concerned about

oaths, and anything that the Court sees fit—about the oath,

it doesn’t concern us, but for me to say they’ll virtually

knock the oath out, I ’m afraid I ’m without authority.

The Court: A great many people feel as you do about

the oath—it doesn’t concern anybody—but, as a matter of

fact, the governing board of the State Democratic Party

[Tr. 5]

has put it in. I expect I ’ll have to keep that county in the

case.

Mr. Rivers: If your Honor please, could not the rule

be dismissed except as to the question of the oath?

The Court: That wouldn’t be dismissal. I ’ll take care

of it in the opinion, and prescribe that they’ll have to wait

in to see what the others will be ordered to do.

Mr. Rivers: Then, as I understand, our return is suf

ficient and satisfactory to the Court except as to the oath?

The Court: That’s true. As far as Greenville, Pickens

and Laurens Counties are concerned, I want to say, gen

tlemen, that i t ’s extremely gratifying to me to have these

representatives, though there are only three, and I feel

quite ashamed that there are only three counties in this

state that recognize not only the meaning of the decision

made by me, because there is no private opinion in this,

but the decision made by the Circuit Court of Appeals and

the Supreme Court of the United States, but much further

4a

Discussion

the supreme law of the land as true Americans. I ’m glad to

see that the governing boards of three counties in this state

are determined to run them, irrespective of any court

action or any coercion or any proceedings or anybody tell

ing them what to do—that they’ve got sense enough, they’ve

got nerve enough, and they’ve got patriotism enough to

make a true, fair and just decision.

Mr. Price, I thank you for your returns, not person

ally, on behalf of the government—on behalf of the Amer-

[Tr. 6]

ican people. I ’m glad to see that some of our citizens re

alize that this country is an American country; that it is

not a country of persecution; that it is not a country of

minorities or parties, groups or religious creeds, races. I

hope that the press will publish the whole or excerpts of

the returns made by these three counties, and my brief re

marks in regard to them.

The County Chairmen of Greenville County, Laurens

County, and Pickens County are dismissed from this cause

and the rule.

In regard to Jasper County, I think i t’s unnecessary to

go further into the matter at this time. The Jasper County

Committee apparently has not met and passed upon all the

issues here. It has, however, taken a unique and perfectly

fair position as far as race is concerned to date. The

Jasper County Committee doesn’t have any enrollment

books. It, in effect, is out of the government of the state

party. As to those internal matters, I have no concern

with them, and they’ll have to be adjudicated in the state

party or in the state courts perhaps as to what effect it

has on their primary election, but they have conformed to

the spirit of the proceedings of the courts, of all the courts

5a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

of this country, in that they are making no discrimination

by reason of race. They are not having any enrollment

books. They are allowing anyone who is a registered

elector to vote. I retain jurisdiction of that county, or

rather the representatives of that county, only for the pur-

[Tr. 7]

pose of seeing that any order issued by this Court in re

gard to the matter of the oath applies to Jasper County as

well as to the others.

Anything further on behalf now—in regard to the re

turns of all the other counties as to the issues that have

been raised here?

I ’ll hear from the plaintiff.

Mr. Eivers: Would it be in order for Mr. Purdy and

me to be excused?

The Court: Unless you desire to remain as interested

spectators.

Mr. Eivers: If your Honor will excuse me, sir.

The Court: You are not required to remain.

[Tr. 8]

W. P. B a s k in , sw orn .

Direct examination by Mr. Marshall.

Q. Mr. Baskin, you are one of the defendants in this

case? A. I am.

Q. You are also chairman of the Democratic Party of

South Carolina? A. I ’m chairman of the State Executive

Committee.

6a

IF. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff-Direct

Q. You are chairman of the State Executive Committee?

[Tr. 19]

A. Yes.

Q. Of the Democratic Party of South Carolina? A.

Correct. Yes, sir.

Q. How long have you held that position? A. Since

April of 1947.

Q. The rules of the Democratic Party of South Carolina,

attached to the return filed by you and other defendants,

are the correct rules of the Democratic Party of South

Carolina? A. They are.

Q. Are they in full force and effect as of this date? A.

They have been in full force and effect. Still are, sir.

Q. Is the printed copy of the rules—have you compared

them with the rules as they were adopted? A. I have not

compared them, but they were compared by the secretary

of the convention, and he told me they were correct. My

reading of them, apparently they are absolutely correct. I

don’t know of any others.

Q. Senator Baskin, will you briefly, merely for the pur

pose of the record, give the procedure by which these rules

are adopted? A. The Democratic Party of South Caro

lina, every general election year, reorganizes by the calling

of precinct club meetings. They elect precinct officers and

delegates to the county Democratic conventions; and there

after, on the first Monday in May, the county Democratic

conventions are held in the forty-six counties of the state.

Those conventions elect their officers and elect a chairman

[Tr. 20]

of the county executive committee, and elect delegates to

the state convention and a member of the state executive

committee, Democratic Party. Thereafter, and on the third

7a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

Wednesday in May, the state convention of the Democratic

Party of South Carolina is held, and at that convention the

delegates from the various county conventions, elected by

the various county conventions, participate in that conven

tion, appoint a rules committee, credentials committee, and

proceed to organize the state convention, by the election of

first temporary president and secretaries and then by

permanent president and permanent secretaries, and the

election of a state chairman of the State Democratic Exec

utive Committee and vice chairman and national committee

man and national eommitteewoman, and adopt the rules of

the party.

Q. Do you not prior to the adopting of the rules, change

the former rules, declare the former ones null and void!

A. Well, the adoption of the rules themselves say in lieu of

the rules previously in force, they are declared to be the

rules of the party—I think that’s the wording of it.

Q. As to the former rules of the Democratic Party as

adopted in 1946, 1944, what changes were made in the pres

ent rules as to the qualifications for club membership? A.

I ’m not quite in a position to answer that, I ’d have to take

the two and compare—I think the—

Q. Club memberships are still restricted to white Demo

crats, which is substantially the same as before? A. Yes,

[Tr. 21]

sir; before, I believe the rules provided for club membership

and voting; that rule was put in two rules, I believe.

Q. And was there not the rule 7, as to the qualifications

for voting in the primaries, which requires that a Negro

present an election certificate, general election certificate,

that rule is in full force and effect? A. That is the rule

adopted by the party.

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

Q. And will be enforced on primary day? A. That rule

adopted by the party, of course, is administered by the

executive committee. I ’m only its chairman, and have no

right to vote except in case of a tie. Those rules, of course,

are the rules of the party, but they, of course, as affected

by any decisions of the courts, would be tempered to that

extent.

Q. Well, absent a decision of some court—in the absence

of a decision of some court, the executive committee and

you as chairman intend to enforce this rule? A. I have no

authority to enforce any rule, no method whereby it can be

enforced.

Q. What is your authority limited to? A. To presiding

over the state executive committee.

Q. And is the state executive committee charged with

enforcing these rules? A. The rules provide that the state

executive committee may make such rules and regulations

as may be necessary to enforce and regulate the rules of the

party.

Q. So is the executive committee operating under these

[Tr. 22]

rules? A. Yes. Yes.

Q. Do you as chairman intend to operate under these

rules? A. Subject, of course, to any decision of the courts

which might indicate that changes are necessary.

Q. As I said before, in the absence of such decision, you

intend to enforce these rules? A. I can’t say I intend to

enforce them, because I have no right to enforce them—I

can only advise with someone who asks me what they are.

Q. Under the rules, will there be another convention this

year? A. Under the rules, the state executive committee

could call a special convention.

9a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

Q. Has the executive committee called such a conven

tion? A. It has not so far.

Q. Has the executive committee taken any action to

amend or change these rules? A. The executive committee

has no authority to change the rules.

Q. Well, I understand that, Senator, but I just want to

know as to whether you intend to do anything about these

rules as to changing? A. Well, the committee has talked

about the matter a number of times, and I ’m not sure

whether changes will be made or won’t be made—entirely

possible they will be made.

Q. What I ’m trying to get, Senator, is, has any action

been taken affirmatively looking toward the future change

of these rules? A. Well, shortly after the rules were

[Tr. 23]

adopted, the executive committee unanimously suggested

that the word “ religious”, I think, that had been objected

to and put in there by inadvertence be eliminated, and it was

eliminated.

The Court: I ’d like to know about that. You

say they suggested—to whom?

The Witness: To me, sir.

The Court: And you changed it?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: Then you have authority to overrule

the convention and change the rules?

The Witness: No, sir; I don’t think so, sir.

The Court: You did it?

The Witness: Yes, sir; I did that.

The Court: By what authority?

The Witness: Under adjournment resolution of

the convention.

10a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

The Court: What does that say?

The Witness: I can’t give it to you word for

word; I can tell you approximately what it says. The

convention adjourned subject to call by the state

chairman, with authority to make such changes as

may be necessary—I believe, such changes—make

such changes as he may deem necessary or for the

best interests of the party—and I construed that to

mean only minor corrections which did not affect ma

terial things.

The Court: Rule 49 says, “ These rules may be

[Tr. 24]

amended or altered at the regular May convention

or any State convention called specially for that pur

pose. Provided notice to amend be given the state

chairman at least five (5) days before the conven

tion. ’ ’

The Witness: Yes, sir. Yes, sir.

The Court: You still think you can change these

rules?

The Witness: We thought so—on the consensus

of opinion, and so long as corrections, inadvertently

done, and did not affect material changes.

The Court: You mean by that you thought you

could change anything that you thought was change

able and you wanted to change ?

The Witness: No, sir; no, I don’t.

The Court: You did make some changes in the

oath, didn’t you?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: You struck out the word “ religious” ?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

-11a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

The Court: You struck out the word “ under

stand” ?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: In other words, the oath read, “ I

further solemnly swear that I understand, believe in

and will support the principles of the Democratic

Party of South Carolina?”

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: You thought it would clarify the

oath to strike out the word “ understand”, so that

[Tr. 25]

the voter would swear he would believe in something

he didn’t understand—was that the object?

The Witness: No, sir.

The Court: Well, what was the object? Why did

you strike out the word “ understand”—a man

swears to something he doesn’t understand—it was

objectionable to swear to something he understands?

The Witness: No, sir.

The Court: Mr. Baskin, just tell me what it

means. I ’m interested in the mentality of these

changes and of the committee-—how did the com

mittee figure out such a thing as that ?

The Witness: Someone in the committee—I

don’t remember who it was—-

The Court: You don’t remember who it was—

it would be interesting ?

The Witness: No, sir. Suggested that the word

“ understand” should be stricken—that it really was

surplus, I think.

The Court: It was surplus for a person to under

stand what he swears to, is that your opinion, too?

12a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

The Witness: No, sir. No, sir. That the word

“ believe” in there was all that was necessary, the

other was simply added to—

The Court: Now, which is the oath that is the

oath of the party now that you intend to enforce, the

[Tr. 26]

one adopted by the convention or the one amended

by you at the suggestion of your committee!

The Witness: The oath in these rules.

The Courts: The amended will be presented at

the primary?

The Witness: That will be presented unless it is

changed or unless some—

The Court: It has been your intention up to this

time to do that?

The Witness: I ’ve made the statement before,

we are still considering changes of the oath, and the

committee has not foreclosed that possibility, and if

we were to suggest changes that were material, why

the convention of course would have to be called.

The Court: You don’t think it’s material for a

man to say whether he understands an oath or not?

The understanding of an oath is not, to your mind,

or the mind of your committee, a material thing?

I t ’s all right for a man to say “ I believe” without

understanding—you think that’s a wholly immaterial

matter, don’t you?

The Witness: Judge, I don’t quite agree.

The Court: You don’t care to commit yourself

on that?

The Witness: Sir, anything I believe, I under

stand, I think, sir.

13a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

The Court: But you are going to make people

[Tr. 27]

generally swear to what they believe without under

standing?

The Witness: No, sir, it was not that intention.

The Court: Well, leave it as it is. Proceed.

Q. Do you or the committee, while contemplating the

changing of the oath, contemplate the changing of the bot

tom: “ I further solemnly swear that I believe in and will

support the principles of the Democratic Party of South

Carolina, and that I believe in and will support the social

and educational separation of races.

“ I further solemnly swear that I believe in the prin

ciples of States’ Eights, and that I am opposed to the pro

posed Federal so-called F. E. P. C. law.” Any discussion

about changing that? A. There has been some discussion—

yes.

Q. Do you consider that material or not? A. That is a

debatable question.

Q. That is a debatable question — you don’t know

whether i t’s material or not? A. Debatable question.

Q. As the matter stands, it will be required as a pre

requisite to voting in the August primary, is that correct?

A. Unless the committee changes, or an order of the Court

directs us otherwise. The party intends to comply with all

orders of the Court.

Q. The same as to the rule as to enrolling? . A. Yes, sir.

Q. In other words, unless a temporary injunction is

[Tr. 28]

granted, Negroes will be prevented from enrolling solely

because of their race? A. I wouldn’t say that; no, sir.

14a

IF. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

Q. Well, are yon going to follow the rules or not? A.

That enrollment provision has been construed in a number

of different ways. In various counties they have construed

it in different ways. In some of the counties Negroes have

been allowed to enroll and they have not been purged.

The Court: That was a construction that was

disobedience, wasn’t it—I mean Greenville County

says, “ I won’t follow this rule” ?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: They didn’t construe white to mean

Negroes?

The Witness: I mean the rules and decisions of

the Court together.

The Court: How do you construe the decision of

the Court—by the way, let me ask you this: The

procedure by which the precinct clubs meet, county

and state conventions, as you described, were sub

stantially as you described them in the case of El

more versus Rice?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: You are familiar with that case?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: You are familiar with the opinion in

that case?

[Tr. 29]

The Witness: Fairly so, yes, sir.

The Court: Well, you read it?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: What do you think this means: “ The

prayer of the complaint for a declaratory judgment

will therefore be granted by which it will be adjudged

that the plaintiff and others similarly situated are

15a

TV. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

entitled to be enrolled and to vote in the primaries,”

you don’t consider that in any way binding upon

you? Did you know that was in there?

The Witness: Yes, sir; I ’ll have to—

The Court: Then you went and joined with your

conferees and colleagues in adopting Rule 6, which

says the qualifications for club membership shall be

a white Democrat; and then in Rule 7 you provide

for a dual system of voting, one for enrolled voters—

that is, whites—and one for Negro voters with a

registration certificate? Yon knowingly did that?

The Witness: The rules as adopted, Judge, were

not unanimous by any means.

The Court: I don’t ask if the rules as adopted

were unanimous; I asked you if you had a part in it,

and you were a part of the committee of the drafters

of that kind of a resolution?

Mr. Tison: Now, your Honor—

The Court: I ’m going to ask this witness what

I want. Sit down.

Mr. Tison: I demand the right to—

[Tr. 30]

The Court: Sit down.

Mr. Tison: Object as a member of the bar.

The Court: I passed an order in this case. I

gave a decision. This witness is head of the Demo

cratic Party of South Carolina. I wanted to know

why—

Mr. Tison: I suggest to your Honor that he has

the right to refuse to answer your question.

The Court: All right. If he refuses to answer,

let him do it. You refuse to answer, Mr. Baskin?

16a

IF. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

The Witness: No, sir.

The Court: Do you answer it?

The Witness: Yes, sir; I ’ll answer any question

you ask, Judge.

The Court: Answer it then.

The Witness: In the preparation of the rules, I

had serious disagreement with some members of the

committee, sir, serious disagreement, on question of

policy that the party should follow, and I was over

ruled in it.

The Court: Well, I want to be fair to you. I ’m

asking you the question in the face of your attor

ney’s objection, not—

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: Not to show you devised this. I

want to give you the opportunity to say you didn’t

do it—that’s my understanding?

[Tr. 31]

The Witness: I have disagreed with some of the

rules, yes, sir.

The Court: You bowed to the vote of the major

ity?

The Witness: The vote of the majority put that

on us, sir. The rules as they have come out, while

I have made certain statements, I have never made

a statement, sir, that a Negro could not be enrolled,

and I have never made a statement he should be

purged. I have been requested for statements along

that line, but I have never made one, sir.

The Court: In other words, the rules are the rules

of the convention and the executive committee and

not your rules?

17a

TV. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

The Witness: They are not my rules; yes, sir.

The Court: Very good. Proceed.

Q. As to your county, what about your county, Senator

Baskin? A. My county had several Negroes to offer to

enroll and were enrolled and not purged.

Q. When was that? A. Before the books closed on the

22nd of June.

Q. About how many, if you know? A. I don’t know—

some several—those who did apply is what I understand.

The Court: I didn’t quite catch that. Did he

say some Negroes had enrolled in his county prior

to the closing of the books?

The Witness: Yes, sir; prior to the closing of

the books and were not purged.

[Tr. 32]

The Court: Your county is what—for the record?

The Witness: Lee County.

The Court: In Lee County, the custodian of the

books—

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: I assume with the acquiescence of the

county committee?

The Witness: I don’t know.

The Court: In Lee County they allowed some

Negroes to enroll.

Mr. Marshall: And, sir, they were not purged?

The Court: They have not been purged ?

The Witness: No, sir; they have not been.

The Court: After enrolling.

Mr. Marshall: If your Honor please, for the bene

fit of the record, as to the material facts necessary

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Direct

for the Elmore case, I could develop them again from

Senator Baskin, but I would assume the other side

would not contest the testimony of Senator Baskin

and the stipulations in the Elmore case are accurate

and correct for the purpose of this or any other case1?

The Court: What parts of them are pertinent?

He’s described—they are very pertinent there—he

doesn’t know whether the organization was a private

club or exercising a public function—we know that

now. That was the only issue in that case. I don’t

think anybody in that case ever attempted to say

the primary as conducted under state law had a dual

[Tr. 33]

system of enrollment, white or black. They said it

was a private club, and the laws didn’t apply to it.

That’s been decided now. If there’s anything in there

material, you might call my attention to this.

Q. The only thing—you remember your testimony in the

Elmore ease ? A. I don’t recall it right now.

Q. You recall it in general? A. Oh, yes.

Q. About how the party operated? A. Oh, yes.

Q. Has there been any fundamental difference in the

way the party operates this year from your prior testi

mony? A. No, sir; not generally. Operates the same as

before.

The Court: Practically the same, with the excep

tion of the new enrollment, designation of whites and

Negroes, and the oath—those are about the material

things ?

The Witness: Yes, sir; those are what I re

member.

19a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Cross

The Court: Dates and time—not material things?

The Witness: That’s correct.

Q. Since this time is it true that Democractic candidates

have continued to be elected to office in that election? A.

I am not in a position to tell you.

Q. Were any Republicans elected in 1946? A. No, none

in the actual primary. Of course, there have been primaries

since then, I think—at least elections—no primaries since

then.

[Tr. 34]

Cross examination by Mr. Tison.

Q. Mr. Baskin, there is attached to the return, which is

verified by you, a copy of the rules. That’s a correct copy?

A. Yes, sir.

The Court: Now, that’s a correct copy as

amended by the executive committee?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

Q. And the oath—

The Court: I just want to get for the record very

definitely what was the oath prescribed by the con

vention and what changes were made.

Mr. Tison: So do I. I want the record to show

definitely and I want the record to show that this

copy attached to the original return is before the

Court in evidence.

The Court: That’s the one as amended?

Mr. Tison: Yes, sir.

The Court: But the original resolution had “ un

derstand” in it and had “ religious” in the places

indicated by Mr. Baskin in his testimony.

20a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Cross

Mr. Tison: I wouldn’t know one thing about that.

I ’m only offering the copy attached to the return.

The Court: Well, I would know; I ’ve gotten it

from Mr. Baskin, and I of course believe him. He

made the statement. I accept his testimony in per

fectly good faith.

[Tr. 35]

Mr. Tison: I offer that in evidence so that there

may be no question about the rules of the party be

ing before the Court.

Q. When was the state convention of the Democratic

party of South Carolina held? A. May 19, 1948.

Q. Where was it held? A. In Columbia.

Q. In the Township Auditorium? A. Yes.

Q. Was the convention open to the press and to the

public? A. It was.

Q. Do you know whether or not it was attended by a

member or representative of the Progressive Democratic

party of this state? A. Do I know the member?

Q. No, do you know whether at that convention there

was in the audience a member of the Progressive Demo

cratic party? A. A member was pointed out to me.

Whether it was a member or not, I don’t know.

Q. Pointed out to you as a member of the Progressive

Democratic party? Was his name given to you? A. I don’t

recall it. I think it was, but I don’t recall it.

Q. All right. Were the rules as adopted at that con

vention made public? A. They were.

[Tr. 36]

Q. Were they printed and distributed to anyone who

asked for them ? A. They were.

21a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Redirect

Q. Is the Progressive Democratic party of South Caro

lina a different party from the Democratic party of South

Carolina? A. We so understand it to be.

The Court: What did you say ?

Mr. Baskin: We do understand it to be.

The Court: Do you know anything about it?

The Witness: The only thing I know about it is

what I see in the paper.

Q. You attended the National Convention at Philadel

phia? A. I did.

Q. When? A. This past week.

Q. Did the Progressive Democratic Party from South

Carolina have representatives seeking to be seated in the

representatives of the Democratic party? A. They did.

Redirect examination by Mr. Marshall.

Q. Senator Baskin, since the Democratic convention

adopted the rules, you say there’s been wide publicity given

to the rules? A. They were published, and people who

wanted them could write in for them.

Q. Since that time, has not the executive committee met

[Tr. 37]

more than once on the question as to what should be done

about three particular rules involved in this case ? A. 1

think they have met twice.

Q. Is it not true that those meetings have been given

wide publicity in the daily press? A. I think the press has

reported.

Q. When was the last meeting—the closed session? A.

I can’t recall the date. I t ’s been about two or three weeks

ago.

22a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Redirect

Q. About two or three weeks ago—in Columbia, was it

not! A. That’s correct.

Q. Was it not called for the express purpose, one of the

express purposes, to consider what should be done about the

three provisions of these rules involved in this case! A. It

was called for the purpose of discussing* together the rules

of the party in the light of various suggestions that have

come to me by letters and otherwise.

Q. Didn’t those suggestions include those three rules?

A. Oh, yes; it included those three and some others.

Q. Involved—have you as chairman of the state com

mittee ever invited a Negro to any of your meetings at any

time at any place? A. No, I have not.

Q. Have you ever had any Negroes at any of your meet

ings at any time any place? A. I don’t recall any, except

at the state convention some were in the audience around.

[Tr. 38]

Q. In the audience you saw some? A. Yes, sir.

Q. For example, have you ever invited any in your own

county? A. No.

Q. Have they ever been welcome? A. Well, the party

has had its meetings, and I, for one, don’t know of any that

have ever been turned away.

Q. Have any come to be admitted? A. Come to be ad

mitted ?

Q. Come to be admitted to the meeting? A. I can’t an

swer—I just don’t know.

Q. Have they ever been invited? A. I don’t think they

have ever been invited.

Q. Since or rather just prior to the Democratic Conven

tion, where you say the Progressive party sent delegates

seeking to be seated, had you ever invited a Negro to par-

23a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Redirect

ticipate in your meetings, prior to the National Conven

tion? A. Let me understand you—I want to be perfectly

frank.

Q. What I am trying to get at, Senator Baskin, is it not

true that the Progressive party, the members of that party,

as Democrats, want just as much to be in the regular Demo

cratic party as anybody else! Isn’t that true, of your own

knowledge? A. I don’t know about that.

Q. After the decision in the Elmore case, did not repre-

[Tr. 39]

sentatives of the Progressive party seek to come into the

Democratic party if they could get elected to the county con

ventions and state conventions ? A. I understand in some,

possibly one or two counties, they made some move to get in.

Q. And were they not excluded and prevented from

taking part in those selections ? A. The only one I know of

where they appeared, they took part in it.

Q. In the convention ? A. Took part in the club meeting

organizing for the convention.

Q. Which club was that? A. I think it was Dillon

County.

Q. Dillon County? A. I think so.

Q. Did you attend the meeting in your own county? A.

I did.

Q. Were any Negroes there? A. None were there.

Q. Is it true that Dillon County selected Negroes to at

tend the state convention? A. I can’t answer for you, be

cause I just don’t know. None came.

Q. Isn’t it true you ruled they could not attend it be

cause they were Negroes? A. No, no; I did not.

[Tr. 40]

24a

W. P. Baskin—For Plaintiff—Redirect

Q. Was that done? A. No, that was not done—not be

cause they were Negroes.

Q They happened to be Negroes? A. Someone asked

me for a statement as to what the rules of the party per

mitted at that time, and the reorganization rules permitted

only a member of the party to help reorganize.

Q. Don’t your rules also provide they be white Demo

crats—also provide? A. You mean for membership?

Q. For any action in the party? A. Yes.

Q. Then, under your rules, I ask you again, is a Negro

eligible to take part in any of your deliberations of any

kind? A. Under the rules of the party the membership is

composed of whites, and Negroes are permitted to vote—

that’s under the party rules.

Q. Can they vote in the club meetings? A. Can they

vote in the club meetings?

Q. In the club meetings ? A. They haven’t had any since

then, and no question.

Q. They haven’t had any club meetings since the Elmore

decision? A. Since the convention was reorganized.

Q. Well, prior to this 1948 convention, were Negroes

permitted to take part in the club meetings ? A. I know of

only one instance where they appeared.

[Tr. 41]

Q. That was Dillon? A. And they took part there.

Q. Then when they came to the convention they were

denied seats? A. I can’t answer for you because I just

don’t know.

Q. All right. Did you see any Negroes seated as dele

gates at the state convention ? A. I did not, no.

Q. Well, get back to the other—did Negroes take part

in county conventions this year? A. As far as I know,

25a

W. P. Baskin—-For Plaintiff—-Recross

none did, unless it was at Dillon, and I ’m not just sure

about that. I have no knowledge of it.

Recross examination by Mr. Tison.

Q. Mr. Baskin, the executive committee opened and

closes the book of the party at the time, is that correct?

A. No, Mr. Tison, the rules provide specifically when the

books are to open and close.

Q. All right. According to the rules, the books opened

when? A. On the fourth Tuesday in May.

Q. And closed when? A. I think it’s the last Tuesday

in June, or fourth Tuesday in June, the 22nd.

Mr. Baskin: Anything further ?

Mr. Marshall: Except this question: The books

could be reopened, could they not?

Mr. Baskin: Certainly. They could be reopened

by lawful authority.

[Tr. 42]

By Mr. Tison.

Q. As far as your party is concerned, could anyone re