Gulf Oil Company v. Bernard Brief of Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

March 5, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gulf Oil Company v. Bernard Brief of Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1981. 63d6dcf5-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96475119-0aad-4937-a09e-ef632b57f31d/gulf-oil-company-v-bernard-brief-of-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 09, 2026.

Copied!

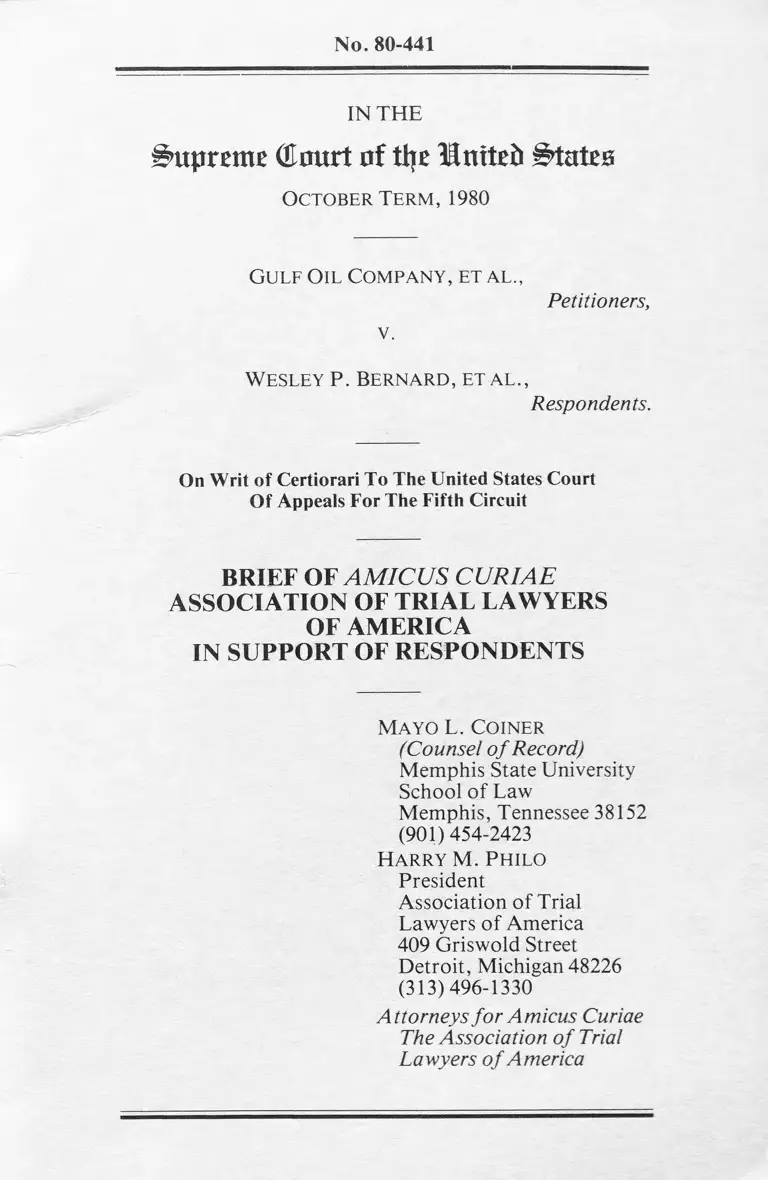

No. 80-441

IN THE

Supreme (ta rt of tijr Btritrd Stairs

October Term , 1980

Gulf Oil Company, et al„

Petitioners,

v.

Wesley P. Bernard , et a l .,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari To The United States Court

Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit

BRIEF OF A M IC U S CU RIAE

ASSOCIATION OF TRIAL LAWYERS

OF AMERICA

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Mayo L. Coiner

(Counsel o f Record)

Memphis State University

School of Law

Memphis, Tennessee 38152

(901)454-2423

HARRY M. PHILO

President

Association of Trial

Lawyers of America

409 Griswold Street

Detroit, Michigan 48226

(313)496-1330

Attorneys fo r Amicus Curiae

The Association o f Trial

Lawyers o f America

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

Page

Table of Authorities................................................. i

Statement of In ter est .............................................. l

Summary of Argum ent.............................................. 3

Argument

I. The District Court’s Order Is an Unconstitu

tional “ Prior Restraint’’ on Speech and Con

duct ........................... 4

II. The District Court’s Order is Unconstitution

ally Vague............................................................ 10

III. The District Court’s Order is Unconstitution

ally Overbroad and Ignores Reasonable Alter

natives...................................................................12

IV. The Purported Exclusion from the District

Court’s Order of One Asserting a Constitu

tional Right to Communicate With a Class

Member Is Not a Sufficient Protection of

First Amendment Rights.................................. 16

VI. There is No Conflict Between Circuits as to the

Validity of the District Court’s Order...............19

Co nclusio n ................................................................... 22

T A B L E O F A U T H O R IT IE S

Cases: Page

Arnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S. 134 (1974)........................ 15

Baggett v. Bullitt, i l l U.S. 360 (1964)........................... 11

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58

(1968)......................................................................... 4

Bernard v. Gulf Oil Co., 619 F.2d 459 (5th

Cir. 1980) ............................................ 3, 10, 17, 18, 19

Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 (1941)....................13

Brotherhood o f Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia

ex rel State Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964)........................... 8

Carroll v. Commissioners o f Princess Anne,

393 U.S. 175 (1968)............................................... 6, 12

Chicago Council o f Lawyers v. Bauer, 522

F.2d 242 (7th Cir. 1975).................. 5, 7, 12, 13,18,19

Coles v. Marsh, 560 F.2D 196 (3d Cir. 1975).......... 19, 20

Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367 (1947) ........................... 13

Gompers v. Buck Stoves & Range Co., 221

U.S. 418(1911)........................................ 17

Hirschkop v. Snead, 594 F.2d 356

(4th Cir. 1979).................................. 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 19

In re Norton, 622 F.2d 917 (5th Cir. 1980)........... .........20

In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978)............................. 7, 17

In re Timmons, 607 F.2d 120 (5th Cir. 1979)................ 17

NAACPv. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963)...................... 7, 8

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931)....................... 4

Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart, 427

U.S. 539(1976).........................................4 ,5 ,6 , 10, 12

New York Times Co. v. United States, 403

U .S .713(1971).........................................................5,6

I ll

Table of Authorities Continued

Cases: Page

Ohralik v. Ohio State Bar Association, 436

U.S. 447 (1978)................ ......................................... 17

Organization fo r a Better Austin v. Keefe,

402 U.S. 415 (1971).................................................... 5

Pan American World Airways, Inc. v. United

States District Court fo r Central District

o f California, 523 F.2d 1073 (9th Cir. 1975)........... 10

Peals v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., Case

No. 78-68-C5, Slip opinion, (D.C. Kan. 1977)........ 21

Pennekamp v. Florida, 318 U.S. 331 (1946).................. 13

Rodgers v. United States Steel Corporation,

508 F.2d 152 (3d Cir. 1975).................................... 19, 20

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960)................... 13

Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1966)................... 6

Shuttlesworth v. City o f Birmingham, 394

U.S. 147 (1969)........................................................... 5

Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad,

420 U.S. 546(1975).............................................. 4 ,5 ,6

United Mine Workers v. Illinois State Bar

Association, 389 U.S. 217 (1967)............................. 8

United Transportation Union v. State Bar o f

Michigan, 401 U.S. 576 (1971).................................. 8

U.S. v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc.,

497 f .2d 102 (5th Cir. 1974)..................................... 10

Waldo v. Lakeshore Estates, Inc. 433 F.

Supp. 782 (E.D. La. 1977).......................................... 21

Walker v. City o f Birmingham, 388 U.S. 307

(1967) 5

IV

Table of Authorities Continued

Weight Watchers o f Philadelphia, Inc. v. Weight

Watchers International, Inc., 455 F.2d

770 (2d Cir. 1972)................................................ 19, 20

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375 (1962).......................... 13

Zarate v. Younglove, 86F.R.D. 80(C.D.

Calif. 1980)...................................... 7, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS, STATUTES, RULES

AND REGULATIONS:

United States Constitution, First

Amendment......................................................... Passim

Fed R.Civ.P., Rule 23....................................... 8, 11, 14

42 U.S.C. §2000e et. seq., Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended......................

28 U.S.C. §1291 ......................................................... 20

28 U.S.C. §1292 ................... 20

28 U.S.C. §1651 ......................................................... 20

Other Authorities:

Manual fo r Complex Litigation

(1 Pt. 2, Moores Federal Practice, Pt. II,

§1.41 [1979])......................................... 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 19

No. 80-441

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfye Buttrfi States

October Term , 1980

Gulf Oil Company, et al .,

Petitioners

v.

Wesley p . Bernard , et al .,

Respondents.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court

Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit

BRIEF OF A M IC U S CU RIAE

ASSOCIATION OF TRIAL LAWYERS

OF AMERICA

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

The Association of Trial Lawyers of America is a na

tional association composed of lawyers regularly engaged

in the trial and appeal of all types of contested matters, as

well as judges, professors of law, lawyer-administrators,

and other lawyers. The membership of the Association

numbers approximately 40,000. The Association, through

its appropriate officers and committees, has authorized its

participation in this cause as amicus curiae. This brief is

filed with the written consent of all parties.

This appeal involves the use of and the interpretation

of Sample Pretrial Order No. 15—Prevention o f Potential

2

Abuses o f Class Actions as set forth in the Manual for Com

plex Litigation, Part II, §1.41 and as explained in Part I,

§1.41.

At the invitation of the Board of Editors of the Man

ual, the Association has participated in the preparation of

recent revisions of the Manual through an ad hoc commit

tee appointed by the President of the Association. In both

1976 and 1980, the Association expressed to the Board of

Editors their concern with the procedures recommended

in §1.41 and with the chilling effect on precious First Amend

ment rights.

The most recent of those expressions of concern was

contained in the Memorandum Report of the Association

of Trial Lawyers of America to the Board of Editors of

the Manual for Complex Litigation and was dated July 30,

1980:

Preventing Potential Abuse of Class Actions

The Potential abuses recounted in §1.41 of the Man

ual are a source of continuing concern to ATLA. The

types of communications referred to appear not to be

as common as the Board might fear. Perhaps our ex

perience is jaded, however, by naivety or by the possi

bility that these communications are difficult to detect

and often escape exposure. Particularly difficult to

detect are communications which defendants direct

toward class members since, in the usual case, the de

fendant has superior knowledge of the identities and

whereabouts of class members and often has a con

tinuing relationship which lends itself to frequent con

tacts or communications.

The danger perceived in this area, however, is not

with the necessity for preventing potential abuses, but

with the procedures to be utilized to accomplish that

end. In its 1976 Report, ATLA expressed concern over

the potential chilling effect of non-communication

orders and rules on precious First Amendment rights.

We reiterate that concern here and urge the Board to

consider §1.41 in light of the June 19, 1980, en banc

decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the

3

Fifth Circuit in Bernard v. Gulf Oil Co., 619 F.2d 459

(5th Cir. 1980). That decision, which was not rendered

until after preparation of the Tentative Draft, reversed

the very case referred to in the Draft and cited at Foot

note 42c. The potential for inadvertent abuse of con

stitutionally protected freedoms may outweigh the

potential for abuse of the class action process.

The Association appears in this cause as amicus curiae

to express its continuing concern with the effect upon First

Amendment freedoms of the imposition of the order and

rule in §1.41 of the Manual in a non-selective manner and

based upon anticipation of abuse of class action procedures.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This appeal involves the constitutionality of Sample

Pretrial Order No. 15 as recommended and published in

the Manual for Complex Litigation, §1.41 of Parts I and II.

The order purports to prevent potential abuses of class

actions by prohibiting all communication by parties in the

class action and their counsel with actual or potential class

members who are not formal parties in the action. The

Manual recommends that the order be issued pretrial in

all class actions in anticipation of potential abuses. The

order was, in fact, imposed upon counsel and parties in

this Title VII class action when they openly opposed a con

ciliation agreement between the defendants and the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission.

The conduct of plaintiffs and their counsel, which re

sulted in the imposition of this order, was protected activity

under the First Amendment as interpreted and applied by

this Court. Further, the imposition of the order as recom

mended by the Manual and as issued herein is inherently

unconstitutional as a prior restraint on free speech. The

district court was not faced with a threat of “ direct, im

mediate, and irreparable damage” to the judicial process

and the Manual does not contemplate such a threat as the

basis for issuing the order.

4

Apart from the unconstitutional circumstances under

which the order was issued, it is unconstitutionally vague

and overbroad. Its terms are such that no reasonably in

telligent person, lawyer or lay person, could be expected to

understand and abide by the order. Its reach is far beyond

that required by the situation confronting the district court—

and the Manual would not require any threat to the judi

cial process, it would “ anticipate” abuse. No consideration

was given to reasonable, available, less severe alternatives.

The order purports to exclude First Amendment rights

asserted by the parties or counsel. However, the order ob

viously “ chills” the assertion of one’s constitutional rights,

as one would assert them at peril of being held in criminal

contempt of court. Any communication is a per se viola

tion of the order.

No Circuit Court has upheld the validity of the order

issued herein. The Fifth Circuit, sitting en banc, held it to

be unconstitutional in this action. That decision should be

affirmed by the Court.

ARGUMENT

I

THE DISTRICT COURT’S ORDER IS AN

UNCONSTITUTIONAL “ PRIOR RESTRAINT”

ON SPEECH AND CONDUCT

Prior restraints have been viewed with great displeasure

in the American Legal system, due largely to the severe

impact they place on judicially guarded First Amendment

rights. Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931). Though

prior restraints on speech are not regarded as unconstitu

tional per se, this Court has repeatedly stated that “ any

system of prior restraints comes to this court bearing a heavy

presumption against its constitutional validity.” Bantam

Books, Inc. v Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58, 70 (1968). See also Ne

braska Press Association v. Stuart, A ll U.S. 539, 556-59

5

(1976); Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad, 420 U.S.

546, 558-59 (1975); New York Times Co. v. United States,

403 U.S. 713, 714 (1971); Organization fo r a Better Austin

v. Keefe, 402 U.S. 415, 419 (1971). The burden of justifi

cation for a prior restraint is, therefore, far greater than

that imposed in cases dealing only with subsequent restric

tions on freedom of speech.

It is generally accepted that a prior restraint of speech

is a “ predetermined judicial prohibition restraining spe

cified expression . . . ” imposed by a judicial decree, the

violation of which is punishable by a contempt citation.

Hirschkop v. Snead, 594 F.2d 356, 368 (4th Cir. 1979);

Chicago Council o f Lawyers v. Bauer, 522 F.2d 242, 248

(7th Cir. 1975). This punishment of contempt is the prime

distinguishing feature between a “ prior restraint” and a

criminal statute that prohibits certain expression. In a pros

ecution for the violation of the latter an individual is pro

tected by the full panoply of criminal procedural safeguards,

and is free to assert the unconstitutionality of the statute as

a defense. See Shuttlesworth v. City o f Birmingham, 394

U.S. 147 (1969). In contrast, an individual who violates an

injunction is precluded from attacking its constitutional

validity in a subsequent contempt proceeding. Walker v.

City o f Birmingham, 388 U.S. 307 (1967). The proper meth

od of challenge to an injunction lies in a prior application

to the court for modification or dissolution, or in a direct

appeal, not in a constitutional attack after its violation.

Walker, supra, 388 U.S. at 317. As this Court noted in Ne

braska Press Association v. Stuart, supra, a prior restraint

has “ an immediate and irreversible sanction,” the threat

of which doesn’t merely “ chill” speech but rather “ freezes

it.” 427 U.S. at 559.

For a prior restraint to be lawful it “ must fit within

one of the narrowly defined exceptions to the prohibition

against prior restraints.” Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v

Conrad, supra, 420 U.S. at 559. The general rule is that

such restraint is justified only if the expression to be re

6

strained will “ surely result in direct, immediate, and irre

parable damage.” New York Times Co. v. United States,

supra, 403 U.S. at 730. As this Court stated in New York

Times, it is not a question of probabilities or mere specu

lation of harm, but rather a question of whether there was

a substantial certainty of harm, i.e., the “ publication must

inevitably, directly, and immediately, cause an occurrence

of an event kindred to the imperiling of a transport already

at sea. . .” 403 U.S. at 726-27.

There are two additional prerequisites to a constitu

tionally permissible prior restraint. First, the restraint must

be the least restrictive means of preventing the threatened

harm. It must be drawn as narrowly as possible, and it can

not be sustained if reasonable alternatives exist that would

impact less severely on First Amendment rights. Nebraska

Press Association v. Stuart, supra; Carroll v. Commis

sioners o f Princess Anne, 393 U.S. 175 (1968). Second, the

restraint “ must have been accomplished with procedural

safeguards that reduce the danger of suppressing constitu

tionally protected speech.” Southeastern Promotions, Ltd.

v. Conrad, supra, 420 U.S. at 559.

A. The Conduct of a Lawyer in the Course of a

Legal Action is Constitutionally Protected.

The right, indeed, the duty of courts to protect their

procedures and to take all reasonable means of ensuring a

fair trial to every litigant is beyond question; and, clearly,

the courts have the inherent power to take appropriate

remedial measures “ to protect their processes from preju

dicial outside interferences.” Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384

U.S. 333, 363 (1966). When a lawyer engages in conduct

which interferes with those processes, that lawyer is subject

to censure. Id. As an officer of the court, a lawyer has a

higher duty than a lay person to protect the judicial process

and to ensure its fairness; certainly, they are subject to more

disciplinary sanctions. Hirschkop v. Snead, supra, 594 F.2d

7

at 366. So, when the right of a lawyer to free speech con

flicts with the right of litigants to a fair trial, the rights of

litigants must take precedence. Chicago Council o f Lawyers

v. Bauer, supra, 522 F2d at 248.

However, lawyers do enjoy the right of free speech and

an order which denies those First Amendment rights to a

lawyer must be measured against and protected by constitu

tional requirements. The Seventh Circuit has suggested that

we should be even more reluctant to silence attorneys repre

senting a plaintiff class in an action such as this action.

Sometimes a class of poor or powerless citizens chal

lenges, by way of a civil suit, actions taken by our es

tablished private or semi private institutions or govern

mental entities. . . . The lawyer representing the class

plaintiffs may be the only articulate voice for that side

of the case. Therefore, we should be extremely skepti

cal about any rule that silences that voice.

Chicago Council o f Lawyers v. Bauer, supra, 522 F.2d

at 258.

No lawyer could competently prepare a class action for

trial under the restrictions of the district court’s order. They

are prohibited from initiating any contact with potential

or actual class members not a formal party—an essential

source of testimony in a Title VII class action. They may

not even inform those persons that the class action has been

filed on their behalf. Plaintiffs’ lawyers were effectively cut

off from the market place in which free speech should be

tested. Quite possibly, it is a violation of due process to

deny an attorney access to witnesses. Zarate v. Younglove,

86 F.R.D. 80, 97-8 (C.D. Calif. 1980).

To the extent that plaintiff’s lawyers were employed

by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, their First Amend

ment right to contact aggrieved citizens and to counsel them

as to their legal rights, including litigation, has been pre

viously litigated and firmly established by this Court in

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) and the line of cases

following it. See In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978); United

8

Transportation Union v. State Bar o f Michigan, 401 U.S.

576 (1971); United Mine Workers v. Illinois State Bar As

sociation, 389 U.S. 217 (1967); Brotherhood o f Railroad

Trainmen v. Virginia ex rel State Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964).

As in Button, the subject matter of the case at bar is

racial discrimination. The only difference is that in the in

stant case the employees had a choice between a conciliation

offer and a lawsuit, whereas in Button there was no con

ciliation offer and the choice was whether or not to partici

pate in a lawsuit.

On authority of the Button line of cases, the communi

cations between formal parties to the suit and potential

class members, also forbidden by the plenary order, is at

least equally protected activity under the First Amendment.

See United Transportation Union v. State Bar o f Michigan,

supra; United Mine Workers v. Illinois State Bar Associa

tion, supra; Brotherhood o f Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia

ex rel State Bar, supra. As this Court stated in United Trans

portation Union, “ The common thread running through

our decision in NAACP v. Button, Trainmen, and United

Mine Workers is that collective activity undertaken to ob

tain meaningful access to the courts is a federal right with

in the protection of the First Amendment.” 401 U.S. at 585.

B. The District Court’s Order Was Constitutionally

Infirm in Its Genesis.

The order imposed upon counsel and parties by the dis

trict court, hereafter referred to as the “Bernard order,”

was taken verbatim from the Manual fo r Complex Litiga

tion, Part II, §1.41, Sample Pretrial Order No. 15. The

accompanying text, Part I, §1.41, exhorts trial judges “ to

anticipate abuse” in class actions under Rule 23, sets forth

“ potential abuses,” and recommends “ timely action” by

local rule, by order, or by both means. Clearly, the thrust

of the text is that the district courts should apply the recom

mended restrictions on communications with class members

9

prior to the occurrence of, or even the threat of, any abuse

of the class action process. Obviously that approach can

not meet the “ direct, immediate, and irreparable damage”

test. Far from protecting an imperiled “ transport already

at sea,” the Manual recommends issuance of the order when

the vessel is still at the dock, “ anticipating” the voyage.

Inconsistently, the Manual acknowledges that these

“ potential abuses” occur rarely:

It must be noted however, that generally, the experience

of the courts in class actions has been favorable. The

aforementioned abuses are the exceptions in class ac

tion litigation rather than the rule. Nevertheless, they

support the idea that it is appropriate to guard against

the occurrence of these relatively rare abuses by local

rule or order. Manual, Part I, §1.41, pgs. 36-37 (em

phasis supplied).

“ Support” hardly rises to a threat of “ direct, immediate,

and irreparable damage” to the judicial process.

The Manual does caution that the recommended order

“ is not intended to be either a permanent or an absolute

prohibition of contact with actual or potential class mem

bers,” and proceeds to recommend a prompt hearing after

entering the order for the purpose of relaxing the order and

for the presentation of proposed communications with class

members. The final paragraph of the recommended order

provides for that hearing. Interestingly, this was the one

paragraph of the recommended order omitted by the trial

court in the Bernard order.

This Court has never spoken on the question of what

degree of consideration should be given to the recommenda

tions of the Manual fo r Complex Litigation. We would

acknowledge that the Manual is entitled to great respect;

however, we would also contend that it is not entitled to the

deference of regulations issued by agencies charged with

the enforcement of Acts of Congress. The Ninth Circuit

has limited the role of the Manual as a source of judicial

authority, “ . . .in any case, the Manual cannot serve as a

10

source of judicial power because the committee that drafted

it possessed authority only to issue recommendations. See

Manual fo r Complex Litigation, Xiii - X ix (1973).” Pan

American World Airways, Inc. v. United States District

Court fo r Central District o f California, 523 F.2d 1073,

1078 (9th Cir. 1975).

The fact that the Bernard order involves the judicial

administration of justice does not bring it within a recog

nized exception permitting prior restraints. In fact, quite

the opposite is true. Even in the context of a criminal de

fendant’s right to a fair trial “ the barriers to prior restraint

remain high and the presumption against its use continues

intact.” Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart, supra, 427

U.S. at 570. Our courts have articulated standards for judg

ing when a prior restraint will be constitutionally permissi

ble in the context of the fair administration of justice. The

Fifth Circuit and others have held that “ [Bjefore a prior

restraint may be imposed by a judge, even in the interest of

assuring a fair trial, there must be an imminent, not merely

a likely, threat to the administraiton of justice. The danger

must not be remote or even probable; it must immediately

imperil.” U.S. v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc.,

497 F.2d 102, 104 (5th Cir. 1974). This standard comports

with the New York Times test of substantial certainty of

“ direct, immediate, and irreparable harm.” Clearly, the

Bernard order fails to meet the requisite standard both in

its conception and by reason of the complete absence of

findings by the trial court indicating any imminent threat

to the administration of justice. Bernard v. Gulf Oil Com

pany, supra, 619 F. 2d at 466.

II

THE DISTRICT COURT’S ORDER IS

UNCONSTITUTIONALLY VAGUE

The order imposed in this action is also unconstitu

tional because it is impermissibly vague.

11

Vague rules that restrict expression also offend the

first amendment because they chill freedom of speech.

Their uncertain meanings require those persons who

are subject to the rule to “ steer far wider of the unlaw

ful zone, . . . than if the boundaries of the forbidden

areas were clearly marked.” Baggett v. Bullitt, 377

U.S. 360, 372, 84 S.Ct. 1316, 1323, 12 L.Ed.2d 377

(1964).

Hirschkop v. Snead, supra, 594 F.2d at 371.

The order sets forth four specific areas of communi

cation with class members which are prohibited to both

lawyers and lay parties:

(a) solicitation directly or indirectly of legal represen

tation of potential and actual class members who are

not formal parties to the class action; (b) solicitation

of fees and expenses and agreements to pay fees and

expenses from potential and actual class members who

are not formal parties to the class action; (c) solicita

tion by formal parties to the class action of requests

by class members to opt out in class actions under sub-

paragraph (b) (3) of Rule 23, F.R.Civ.P. and (d) com

munications from counsel or a party which may tend

to misrepresent the status, purposes and effects of the

class action, and of any actual or potential Court orders

therein which may create impressions tending, without

cause, to reflect adversely on any party, any counsel,

this Court, or the administraiton of justice.

But, these four prohibitions are introduced with the

statement, “ The communications forbidden by this order

include, but are not limited to . . . .” What other communi

cations are forbidden? The only clue within the order fol

lows the recitation of the four forbidden areas: “ The obli

gations and prohibitions of this order are not exclusive. All

other ethical, legal and equitable obligations are unaffected

by this order.”

No lawyer, far less a lay party, could determine with

any certainty from the above language what they may or

may not do thereafter in the preparation of the action for

trial.

12

“ All other ethical, legal and equitable obligations”

might be meaningful to a lawyer. It should mean, “ Conduct

yourself as an ethical lawyer.” If so, it is superfluous; if

not, it is unconstitutionally vague. But what does it mean

to a lay party?1

Paragraph (d), above, prohibits communications

“ which may tend to misrepresent.” It would be difficult,

but feasible, to abide by an order which prohibited com

munications “ which misrepresent;” it is impossible to in

terpret safely “ which may tend to misrepresent.” This

phrase was found to be both unconstitutionally vague and

overbroad in Zarate v. Younglove, supra, 86 F.R.D. at 103.

And, how does one comply with the prohibition against

misrepresenting “ potential Court orders?” That requires

a prescience which few trial lawyers, or judges, possess!

These vague provisions would certainly “ chill” the

activities of parties and counsel. The wise person seeing a

sign, “ Danger—Thin Ice,” will give it a wide berth; the

cautious will not go ice skating.

I ll

THE DISTRICT COURT’S ORDER IS

UNCONSTITUTIONALLY OVERBROAD AND

IGNORES REASONABLE ALTERNATIVES

A constitutional prior restraint must be carefully drafted.

It must be drawn as narrowly as possible and it will not be

sustained if there are reasonable alternatives which will have

a less severe impact on First Amendment rights. Nebraska

Press Association v. Stuart, supra; Carroll v. Commissioners

o f Princess Anne, supra.

‘Compare, Chicago Council o f Lawyers v. Bauer, 522 F.2d 242,

255-56 (7th Cir. 1975) holding unconstitutionally vague the phrase,

“ or other matters that are reasonably likely to interfere with a fair

trial.” Accord, Hirschkop v. Snead, 594 F.2d 356, 373 (4th Cir. 1979).

13

A. The District Court’s Order Is

Unconstitutionally Overbroad

In a series of decisions this court has held that, even

though the governmental purpose be legitimate and

substantial, that purpose cannot be pursued by means

that broadly stifle fundamental personal liberties when

the end can be more narrowly achieved. The breadth

of legislative abridgement must be viewed in the light

of less drastic means for achieving the same basic pur

pose. Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479, 488 (1960)

(footnotes omitted).

With the above constitutional guidelines from this

Court, the lower courts have adopted varying standards to

determine to what extent judicial orders may curtail the

First Amendment rights of litigants and counsel to com

ment on pending litigation. In Hirschkop v. Snead, supra,

the Fourth Circuit held that rules proscribing comments on

pending litigation are constitutionally prohibited unless

there is a “ reasonable likelihood” that such dissemination

will interfere with the administration of justice. 495 F.2d

at 370. In Chicago Council o f Lawyers v. Bauer, supra, the

Seventh Circuit adopted a narrower and more restrictive

standard, holding that comments on pending litigation can

be constitutionally restrained only if they pose a “ serious

and imminent threat of interference with the fair admini

stration of justice.” 522 F.2d at 249. The two courts agreed

that rules prohibiting lawyers’ comments about civil trials

were unconstitutional and the Fourth Circuit included all

bench trials in their ruling. 594 F.2d at 371-72, 373; 522

F.2d at 257-59. Of course, being a Title VII action, the ac

tion here involved was a civil action which should have

resulted in a bench trial. The courts are in unanimous agree

ment that the interest of the judiciary in the proper admini

stration of justice does not license a blanket exception to

the First Amendment. See Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375

(1962); Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367 (1847); Pennekamp

v. Florida, 318 U.S. 331 (1946); Bridges v. California, 314

U.S. 252 (1941).

14

The order at issue is inherently overbroad as published

in the Manual and unconstitutionally overbroad as issued.

It was taken verbatim from the Manual with no attempt to

apply it specifically to the alleged abuses. Consequently,

the order prohibits abuses which could not occur in this

action and it authorizes conduct which could not occur in

this action.

For example, paragraph 2 (c) of the Bernard order

forbids solicitation of requests to opt out under Rule 23

(b) (3). This conduct could not occur in this action. First,

Rule 23 (b) (3) contains no provision for a class member to

opt out; one opts out under Rule 23 (c) (2) (A). Secondly,

Title VII class actions are (b) (2) class actions. Rule 23 con

tains no provision for opting out of a (b) (2) class action.

The Bernard order also contains an exception “ in the

performance of the duties of a public office or agency (such

as the Attorney General) . . . .’’ Of course, neither the At

torney General nor any other government attorney was in

volved in this action.

Far from being “ no greater than is necessary or essen

tial,” the Bernard order reached out to forbid all communi

cation “ concerning this action with any potential or actual

class member not a formal party to the action without the

consent and approval of the proposed communication and

proposed addressees by order of this Court.” Simply, the

order established a “ permit” system. Zarate v. Younglove,

supra, 86 F.R.D. at 104.

The alleged threat to the court’s management of this

class action is described by Petitioner as follows:

On May 22, 1976, four days after this action was

filed, attorneys for Respondents attended a meeting

of actual and potential class members (J.A. 115, 118),

and according to affidavits filed in this case, discussed

with the potential class members the issues involved in

this action, answered questions from the audience, and

explained the administrative and legal problems in

herent in fair employment litigation. (J.A. 115, 116,

118).

15

After the meeting, Gulf’s counsel, by emergency

motion, represented to the district court that it had

learned that an attorney for Respondents advised the

participants at the meeting to mail back the checks they

had received from Gulf, since by prosecuting the pres

ent action Respondent’s attorney could recover at least

double the amount which was paid under the concilia

tion agreement. (J.A. 22, 23, 24). Gulf’s emergency

motion sought an interim order limiting communica

tions between potential class members and all parties

and their counsel to this lawsuit. (J.A. 21, 25). On May

28, 1976, District Judge Steger, ruling in Chief Judge

Fisher’s absence, granted Gulf’s motion and entered

the interim order. (J.A. 44).

Brief fo r the Petitioners, pg. 5.

These allegations describe an attack on the conciliation

agreement negotiated between Petitioner and the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission. Even assuming

that the conciliation agreement was entitled to the court’s

protection (J.A. 71-80), a highly debatable issue in itself, or

that Respondents has misrepresented the context and effect

of that agreement, the Bernard order does not specifically

address that issue in any manner. If this issue was intended

to be included in the prohibition of communications “which

may tend to misrepresent the status, purposes and effects”

of the action or “ actual or potential Court orders” or to

reflect adversely on the parties or the court (paragraph 2

(d) of the order, supra), it is unconstitutionally vague and

broad as discussed above.

Indeed, the order in question “ hangs over [people’s]

heads like a Sword of Damocles.” Arnett v. Kennedy, 416

U.S. 134, 231 (1974). Counsel’s decision to seek prior ap

proval of the court before attempting to communicate with

potential class members aptly demonstrates that “ the value

of the sword of Damocles is that it hangs—not that it drops.”

Id.

16

B. The District Court’s Order Ignores the

Reasonable Alternatives.

There was no showing in the district court that reason

able alternatives with lesser impact on the right to free speech

were unavailable. In fact, such alternatives were available.

In Zarate v. Younglove, supra, the district court refused to

issue a restraining order, identical to the one at issue in the

case at bar, on the grounds that it was an unconstitutional

prior restraint on speech, as well as unconstitutionally vague

and overbroad. In doing so, the court delineated what it

considered to be a constitutionally permissible order re

stricting communications between plaintiffs and potential

class members. The court held that the only permissible

order would be one narrowly prohibiting communications

from attorneys who misrepresent the status, purposes, or

effects of the action or any court orders, and which repre

sent a serious and imminent threat to the administration of

justice. 86 F.R.D. at 105. The trial court in the instant case

could have issued such an order, but instead chose a pro

vision that is unconstitutionally broad as a prior restraint

of speech.

In so far as unethical solicitation of clients, fees, and

expenses is involved, the district court simply is not the

proper agency for regulating the ethics of the bar. If and

as unethical conduct by lawyers occurs, the district court

should refer such matters to the appropriate state authorities.

IV

THE PURPORTED EXCLUSION FROM THE

DISTRICT COURT’S ORDER OF ONE ASSERTING

A CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT TO COMMUNICATE

WITH A CLASS MEMBER IS NOT A SUFFICIENT

PROTECTION OF FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHTS.

Petitioners argue that under the Bernard order “ all

expressions assertedly protected by the First Amendment

17

may be made by the parties or their counsel free of re

straint.” (Brief for Petitioners, pg. 33.) Petitioner proceeds

to acknowledge that communications by respondent parties

or their counsel would be tested in criminal contempt pro

ceedings and projects that the determination would be based

upon

. . . the applicable constitutional test for solicitation

in effect at the time the violation is charged. Presently,

this would require an analysis by the court of whether

the solicitation was commercial, under the standards

of Ohralik v. Ohio State Bar Association, 436 U.S.

447 (1978) or whether the solicitation was a form of

political expression under the standard of In re Primus,

supra. Thus, the order’s exception allows any court

imposed prohibition on speech to be constitutionally

challenged by the one charged with its violation and

then only after all the safeguards of the criminal justice

system are fulfilled.37

37. Violations of the order would be punished by crimi

nal contempt since the objective would be to vindicate

the authority of the court. See Gompers v. Bucks Stove

& Range Co., 221 U.S. 418, 441 (1911).

The means of enforcing the order in issue, criminal

contempt, are not disputed. Petitioners acknowledged the

means of enforcing this order before the Fifth Circuit:

the appellees accept that the means of enforcement in

intended is the contempt power of the court, and we

agree.14

14. Contempt here would be criminal because used

to punish past misconduct. In re Timmons, 607 F,2d

120, 123-24 (5th Cir. 1979).

Bernard v. Gulf Oil Co., 619 F.2d 459, 468-69 (5th

Cir. 1980).

And, of course, in that criminal contempt proceeding, the

burden would be upon the attorney or party asserting their

First Amendment rights.

The conditional defense is accompanied by a second

chilling effect, the risk of trial on criminal contempt

charges, with guilt or innocence possibly turning on

18

whether one’s assertion of constitutional protection

has been made in “ good faith.” Moreover, the omis

sions and ambiguities of the order and possible dif

fering constructions as to when, if at all, one is pro

tected against contempt, accentuate the chilling effect.21

21. For example, in addition to the general ban on

communications, subparagraph (a) of paragraph (2)

expressly forbids solicitation. Prudent counsel very

well may conclude that he cannot safely rely upon as

serting constitutional protection in the face of this spe

cific ban. If there is a “ good faith” defense can counsel

be in good faith if he does what he is expressly ordered

not to do? As one commentator has noted:

The proviso exempting constitutionally protected

communication does not eliminate, indeed, it high

lights the overbreadth and resultant chilling effect

of the Manual’s proposed rule.

Note, 88 Harv. L. Rev. 1911, 1922 N. 74 (1975). See

also Zarate v. Younglove, 22 FEP Cases 1025, 1042

(C.D. Cal, 1980).

Bernard v. Gulf Oil Co., 619 F.2d 459, 471 (5th Cir.

1980). See also, Chicago Council o f Lawyers v. Bauer,

522 F.2d 242, 251 (7th Cir. 1975) (Burden upon one

“ charged with violating such a rule . . .” )

It is not at all certain that the “ good faith” belief in

the First Amendment status of one’s non-judicially approved

communications would be a defense in criminal contempt

proceedings. Petitioners have so contended;2 but it is at

best a potential defense and hardly security for the assertion

of the First Amendment rights of respondent parties and

their counsel. As one court has observed, this supposed

defense “ simply exchanges overbreadth for vagueness.”

Zarate v. Younglove, supra, 86 F.R.D. at 103-04. No one

has contended that the mere filing of an alleged First Amend

ment communication is a defense.

2Bernard v. Gulf Oil Co., 619 F2d 459, 470 (5th Cir. 1980).

19

V

THERE IS NO CONFLICT BETWEEN CIRCUITS AS

TO THE VALIDITY OF THE

DISTRICT COURT’S ORDER.

Petitioner asserts that there is a conflict between the

Fifth Circuit’s en banc opinion herein and the Second Cir

cuit’s opinion in Weight Watchers o f Philadelphia, Inc. v.

Weight Watchers International, Inc., 455 F.2d 770 (2d

Cir. 1972). Brief fo r Petitioners, pgs. 13, 21-22 n. 15. In

fact, there is no conflict among the Circuits as to the validity

of the substance of the order issued in this action. No Cir

cuit Court has approved the order issued in this action and

recommended in the Manual fo r Complex Litigation, Part

I, §1.41.3

The Fifth Circuit held the challenged order unconstitu

tional in the instant action.4 The Third Circuit has held that

the content of the order is neither authorized as a local dis

trict court rule5 nor as a district court order.6 The Fourth

Circuit and the Seventh Circuit have declared unconstitu

tional bar association rules designed to achieve many of the

same purposes as the challenged order but not aimed spe

cifically at class actions.7

'The Manual cites Weight Watchers as authority for the almost unre-

viewable discretion of the trial court to regulate communications be

tween counsel and class members and potential class members. Manual

for Complex Litigation, Part I, §1.31 n.33. At best, this is an overstate

ment of the holding in Weight Watchers as discussed later in this sec

tion, infra, at pg. 20.

4619F.2d at 477-78.

5Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp., 508 F.2d 152, 163-65 (3d Cir.

1975). While declining to hold the rule unconstitutional, the court recog

nized that it was a “ prior restraint.” 508 F.2d at 162, 164.

6Coles v. Marsh, 560 F.2d 186, 189 (3d Cir. 1977). Again declining to

rule on a constitutional basis, the court sets forth a requirement for a

“ specific record” showing the threat to the court, Id., which would

satisfy First Amendment requirements.

1 Hirschkop v. Snead, 594 F.2d 356 (4th Cir. 1979) (en banc); Chicago

Council o f Lawyers v. Bauer, 522 F.2d 252 (7t,h Cir. 1975).

20

The order at issue in Weight Watchers, supra, differed

drastically from the order issued herein. The order chal

lenged there was quite specific and designed to remedy a

specific abuse.8 The Second Circuit held that the order was

not a “ final decision” appealable under 28 U.S.C. § 12919

nor reviewable under a petition for mandamus.10 Thus, the

court did not consider the merits of the order involved here

in. Considering the relatively insignificant effect of the order

before the Second Circuit, we do not challenge that decision.

The only potential conflict among the Circuits is whether

this order, when issued, is subject to review prior to a final

judgment. The Third Circuit has held that the order, coupled

with a local district court rule to the same effect, is not re-

viewable under 28 U.S.C. §1292 (a) (1) but is reviewable

under 28 U.S.C. §1651; therefore, they did not reach the

question of whether the order [rule] is reviewable under 28

U.S.C. §1291. Rodgers v. United States Steel Corporation,

508 F.2d 152, 159-65 (3rd Cir. 1975); Coles v. Marsh, 560

F.2d 196 (3rd Cir. 1975) (order reviewed on petition for

writ of mandamus). The Second Circuit would perhaps re

ject those results under the holding of Weight Watchers,

supra; but the issue is totally different from that which they

decided. Since the en banc decision below in this action,

the Fifth Circuit has reviewed and vacated a local district

court rule embodying the recommendations of the Manual

under a petition for writ of mandamus. In re Norton, 622

F.2d 917 (5th Cir. 1980).

There is a conflict among District Courts as to the va

lidity of the order in issue. In Zarate v. Young love, supra,

8In the absence of the assigned trial judge, another district judge issued

the order at issue herein to preserve the status quo. Upon the return of

the assigned judge, a prompt hearing was held and a modified order

issued which restored communication with class members with the right

of the class members’ counsel to be present. It was only the latter order

which was appealed. 455 F.2d at 772.

9455 F.2d at 722-73.

10455 F.2d at 775.

21

the court found the proposed order to be vague and over

broad and posing an impermissible prior restraint. Absent

a showing of a serious and imminent threat, the court de

clined to issue the order. 86 F.R.D. at 94-106. The constitu

tionality of a local district court rule adopted in accordance

with the Manual’s recommendation was upheld in Waldo

v. Lakeshore Estates, Inc. 433 F. Supp. 782 (E.D. La. 1977)

(that rule would now be invalid under the Fifth Circuit de

cision in this case). Without reaching the constitutional

question, the District of Kansas upheld its authority to issue

this same order. The court noted “ that plaintiff’s attorney

files a very great number of asserted class actions in this

court, and the nature and extent of his requested discovery

becomes a point of contention in almost every one.” Peals

v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Company, Case No. 78-

68-C5, Slip opinion, September 13, 1977. The number and

complexity of discovery requests in prior cases is hardly a

proper subject of judicial notice and would scarcely seem

to justify the imposition of the order in question.

As trial lawyers, we recognize the pressures under which

a trial judge performs; so we do not mean to castigate the

trial judge for issuing the Bernard order and ignoring the

alternatives. He was absent when the original order was

issued. Upon his return, the situation consisted of an exist

ing order prohibiting communication, defense attorneys

requesting far greater relief than the situation required—if

any relief was required, and a recognized publication recom

mending, even urging, that he issue the order and assuring

him that his action was not reviewable.

Unfortunately, the result is unconstitutional.

22

CONCLUSION

Therefore, for the foregoing reasons, amicus curiae

Association of Trial Lawyers of America respectfully sub

mits that the judgment of the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Mayo L. Coiner

Memphis State University

School of Law

Memphis, Tennessee 38152

(901) 454-2423

HARRY M. PHILO

409 Griswold Street

Detroit, Michigan 48226

(313) 496-1330

Attorneys fo r Amicus Curiae

The Association o f

Trial Lawyers o f America

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

23

I hereby certify that on March 5, 1981, true and cor

rect copies of the foregoing Brief for Amicus Curiae, the

Association of Trial Lawyers of America, were deposited

in the United States Post Office with first class postage per-

paid and properly addressed to the following parties to this

action and others required to be served:

Jack Greenberg

Patrick O. Patterson

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Barry L. Goldstein

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

Ulysses Gene Thibodeaux

425 Alamo Street

Lake Charles, Louisiana 70601

William G. Duck

P. O. Box 3725

Houston, Texas 77001

Carl A. Parker

449 Stadium Road

Port Authur, Texas 77640

Leroy D. Clark

Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

2401 E Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20506

Drew S. Days, III

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

24

Solicitor General

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

I also certify that all parties required to be served have

been served.

'

« i

g u m

, ■T-r.v-

-

■

1 -£

\

.

.“• s, '"•, ' ■ j m

' |IIb3̂ S€S

■■

B l s i l

„g*--g -', ' _'■ ̂ -, :

■ -i