Rizzo v Goode Tate v Council of Organization on Philadelphia Polica Accountability and Responsibility Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

July 1, 1975

27 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rizzo v Goode Tate v Council of Organization on Philadelphia Polica Accountability and Responsibility Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1975. d622e392-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9667449f-4d8f-4f35-9216-335e78a019ba/rizzo-v-goode-tate-v-council-of-organization-on-philadelphia-polica-accountability-and-responsibility-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed March 05, 2026.

Copied!

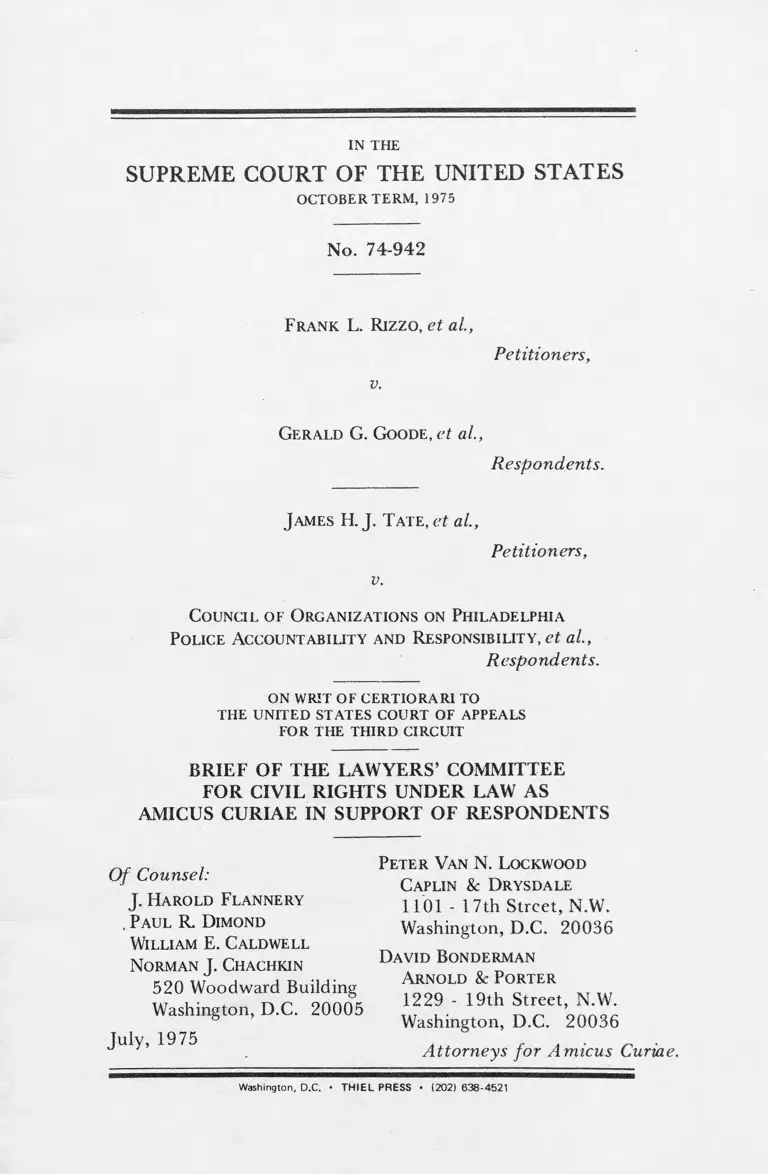

IN THE

SU PR EM E C O U R T O F T H E U N IT E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1975

N o. 74-942

Frank L. Rizzo , et al.,

P etitioners,

v.

Gerald G. Goode, e t al.,

R esp o n d en ts .

J ames H. J. 'Fate, e t al.,

P etitioners,

v.

Council of O rganizations on Philadelphia

Police Account ability and Responsibility, e t al.,

R esp o n d en ts .

on writ of certiorari to

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

B R IE F O F TH E LA W Y ER S’ CO M M ITTEE

FO R C IV IL R IG H T S U N D E R LAW AS

AM ICUS C U R IA E IN SU PPO R T O F R E SPO N D EN TS

O f Counsel:

J. Harold Flannery

, Paul R. Dimond

William E. Caldwell

Norman J. Chachkin

520 Woodward Building

Washington, D.C. 20005

July, 1975

Peter Van N. Lockwood

Caplin & D rysdale

1101-1 7th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

David Bonderman

Arnold & Porter

1229 - 19th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

A tto r n e y s fo r A m ic u s Curiae.

Washington, D.C. • T H IE L PRESS • (202) 638-4521

TABLE OF CONTENTS ^

CONSENT TO FILING ....................................................................... 1

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE .................................................... 2

STATUTE INVOLVED ........................................................................ 2

QUESTION P R E S E N T E D ........................................................................ 3

STATEMENT OF FACTS ..................................................................... 3

ARGUMENT:

The District C ourt’s Order Was Based on Ade

quate Evidence and Is an A ppropriate Form of

Equitable R e l i e f .....................................................................................7

A. The Evidence o f R ecord Shows a Pattern of

Police M isconduct for Which Petitioners Are

Legally Responsible Under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 7

1. Petitioners’ Responsibility ................................................... 8

2. Relief Against Petitioners ................................................... 9

B. The Order o f the D istrict C ourt Is a Wholly

A ppropriate Rem edy for the Violations

F o u n d .............................................................................................. 10

1. The Present Case Presents a Justiciable

Controversy .......................................................................... 11

2. Respondents Have No Adequate Remedy

at Law .............. 15

3. The District C ourt Was Justified in O rder

ing the D epartm ent to Improve its Han

dling of Citizens’ Complaints ........................................ 16

4. Petitioners’ Objections to the Precise

Form of the Trial C ourt’s Decree Are

Wholly U nsupported by Any Evidence of

R e c o r d ........................................................... 19

CONCLUSION ........................................................................................... 21

(0

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page

Cases

Adickes v. S.H. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970) ....................... 19

Alexander v. Rizzo, (E.D. Pa., C.A. No. 70-992) . . . . . . . . 6, 18

Allee v. M edrano, 416 U.S. 802 (1974) ............... 9 ,1 0 ,1 2 ,1 5 ,1 8

Bivens v. Six U nknow n Fed. Narcotics Agents, 403

U.S. 388 (1971) 15

Dom browski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 ( 1 9 6 5 ) .................................. 15

Doran v. Salem Inn, Inc., 43 U.S.L.W. 5039 (June 30,

1975) . ............................................. 14

General M otors Corp. v. W ashington, 377 U.S. 436

(1964) .................................................................................................... 19

Gilligan v. Morgan, 413 U.S. 1 (1973) .............................................. 12

Hague v. CIO, 307 U.S. 496 ( 1 9 3 9 ) ..................................... 9 ,1 4 ,1 5

Laird v. Tatum , 408 U.S. 1 (1972) .................................................... 14

Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F.2d 197 (4th Cir. 1966) .................... 12

M onroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ........................................ 9, 10

O’Shea v. L ittle ton , 414 U.S. 488 (1974) ............................ . 11, 13

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974) ........................................ 15

Schnell v. City of Chicago, 407 F.2d 1084 (7th Cir.

1969) .............................................................................................. 9 ,1 1

Smith v. Ross, 482 F.2d 33 (6th Cir. 1973) ............................ 9

Steffel v. Thom pson, 415 U.S. 452 (1974) ..................................... 14

U nited States v. Spector, 343 U.S. 169 (1952) .............................19

W itherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) ................................ 19

Wood v. Strickland, 95 S. Ct. 992 (1975) ........................................ 15

Wright v. McMann, 460 F.2d 126 (2d Cir.), cert.

denied, 409 U.S. 885 (1972) ......................................................... 9

Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 ( 1 9 7 1 ) ..............................................13

( Hi)

Statutes: ^age

Civil Rights Act of 1 8 7 1 ,4 2 U.S.C. §1983 .............................passim

Other Authorities:

American Bar Association, Standards Relating to the

Urban Police Function (1973) 17

Com m ent, The Federal Injunction as a R em edy fo r

Unconstitutional Police Conduct, 78 Yale L J . 143

( 1 9 6 8 ) ................................................................................................... 10

National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice

Standards and Goals, R eport on Police, M odel

Standards fo r Police Internal Discipline (1973) .............. 17, 20

Note, The Adm inistration o f Complaints by Civilians

Against the Police, 77 Harv. L. Rev. 499 (1964) .................... 17

Note, Developments in the Law —Injunctions, 78

Harv. L. Rev. 994 (1965) 18

The President’s Commission on Law Enforcem ent

and A dm inistration o f Justice, The Challenge o f

Crime in a Free Society (1967) 17

The President’s Commission on Law Enforcem ent

and A dm inistration of Justice, Task Force Report:

The Police (1967) 17

Ruchelman, Models o f Police Politics—New York

City, Chicago, Philadelphia, reprinted in L.

Ruchelman, Who Rules the Police! (1973) ............................... . 8

Schwartz, Complaints Against the Police: Experience

o f the C om m unity Rights Division o f the Philadel

phia District A tto rn e y ’s Office, 118 U. Pa. L. Rev.

1023 (1970) .................................................................................. .9

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1975

No. 74-942

Frank L. Rizzo, et a l,

Petitioners,

v.

Gerald G. Goode, et al.,

Respondents.

J ames H. J. Tate, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Council of Organizations on Philadelphia

Police Accountability and Responsibility, et a l,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS

AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

CONSENT TO FILING

This amicus brief is filed, pursuant to Supreme Court

Rule 42(2), w ith the w ritten consent o f all parties to the

case.

1

2

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Com m ittee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized on June 21, 1963, following a conference

of lawyers called at the White House by the President of

the U nited States. The Lawyers’ Com m ittee is a n on

profit private corporation whose principal purpose is to

involve private lawyers throughout the country in the

struggle to assure all citizens of their civil rights through

the legal process. The Com m ittee includes three form er

A ttorneys General, tw o form er Solicitors General, th ir

teen past presidents o f the American Bar Association, a

num ber of law school deans, and m any of the n a tio n ’s

leading lawyers.

The Lawyers’ Com m ittee and its local com m ittees,

affiliates, and volunteer lawyers have been actively

engaged in providing legal representation to those seeking

relief under federal and state civil rights legislation and

the R econstruction A m endm ents to the C onstitution. As

part of these efforts, the Law yers’ Com m ittee is particu

larly concerned w ith ensuring th a t institutions of govern

m ent at every level in the U nited States are responsive to

the need to p ro tec t and preserve the constitutional rights

of individual citizens. Because the lower courts in this

case properly enforced the constitutional requirem ent

tha t police n o t violate the rights of citizens and entered

an order which will n o t interfere w ith the legitimate

operations of the police, the Lawyers’ Com m ittee files

this amicus brief to urge th a t the decision be affirmed.

STATUTE INVOLVED

The Civil Rights A ct o f 1871, 42 U.S.C. §1983,

provides:

“ Every person who, under color of any statu te,

ordinance, regulation, custom , or usage, of any State

3

or Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any

citizen of the U nited States or o ther person w ithin

the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or im m unities secured by the

C onstitu tion and laws, shall be liable to the party

injured in an action at law, suit in equity , or other

proper proceeding for redress.”

QUESTION PRESENTED

On the basis o f the evidence presented to them , were

the lower courts in this case justified in concluding tha t

the Philadelphia Police D epartm ent has been engaged in a

pattern of violations of the constitutional rights of

citizens, due in substantial part to inadequate supervision

by superior officials o f the conduct o f police officers, and

that the least intrusive potentially effective rem edy for

this pattern o f unconstitu tional action is to require the

Police D epartm ent to set up an adequate internal system

of handling citizens’ com plaints about m isconduct by

individual police officers?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The full factual background of the case is set ou t in the

opinions of the courts below 1 and in the Brief for

Respondents. In brief, the facts are as follows:

Two separate civil rights class actions were brought in

1970 by groups of unrelated plaintiffs against officials of

the City of Philadelphia, including the M ayor, the

Commissioner of Police and various o ther high-ranking

lrThe opinion o f the D istrict C ourt is reported at 357 F. Supp.

1289 and is reproduced beginning at page 65a o f the A ppendix

(hereinafter cited as App.). The opinion of the Court of Appeals is

reported at 506 F.2d 542 and is reproduced beginning at page 4a

of the A ppendix to the Petition for Certiorari (hereinafter cited as

App. Pet. Cert.).

4

police officials, claiming widespread violations of the

constitu tional rights o f Philadelphia citizens by members

of the Philadelphia Police D epartm ent. The tw o actions

were ultim ately consolidated for disposition by the

D istrict Court, and, accordingly, were treated as a single

litigation by the C ourt of Appeals.

A t trial, the plaintiffs presented evidence o f approxi

m ately 40 specific instances of alleged police m isconduct.

The trial judge entered extensive findings of fact with

respect to each incident. With respect to the incidents

presented in Goode, the trial judge found at least seven

instances of m isconduct by the police tow ard these

plaintiffs (principally involving one officer DeFazio)

consisting of illegal arrests (Shaw, Goode), unnecessary

force (Shaw, Goode, Brown, Sisco and Reas), racial slurs

(Brown, Reed) and antisem itic remarks. The trial judge

further found tha t, despite the num erous justifiable

com plaints relating to D eFazio’s conduct, his superiors

never meaningfully disciplined him ,2 no records were

kept of the com plaints, and D eFazio’s repeated record of

m isconduct and the com plaints thereof had no effect

upon D eFazio’s official fitness ratings.3

With respect to the 28 incidents in COPPAR, the trial

judge described in detail the conduct of the police and

found tha t the evidence showed “ widespread” violations

of citizens’ legal and constitutional rights, principally:

(1) arrests “ for investigation” ;

2D eFazio’s tw o short suspensions were bo th w ith pay, i.e.,

unscheduled vacations.

3In fact, as the num ber of instances of m isconduct increased,

D eFazio’s official rating improved.

5

(2) m istreatm ent—including bo th unlawful arrests

and beatings—of citizens who question the

propriety of police conduct in specific cases;

(3) im proper charges of resisting arrest when the

arrest was unlawful to begin w ith; and

(4) extrem e overreaction, frequently including use

of unnecessary force and assaults and beatings

of civilians, in connection w ith actual or re

ported assaults on police.

The trial court concluded tha t this repeated m iscon

duct was the natural and foreseeable result o f the

institutional failure o f the D epartm ent to supervise police

officers’ conduct or to discipline or otherwise control

officers who act unlawfully or unconstitutionally . Thus,

the court found tha t where police officers act unlawfully

“ little or nothing is done [by the D epartm ent] to punish

such infractions, or to prevent their recurrence.” (App. at

126a, 357 F. Supp. at 1319). The court also found tha t it

is “ the policy of the departm ent . . . to avoid or minimize

the consequences of proven police m isconduct . . . .”

(App. at 124a, 357 F. Supp. at 1318).

In this regard, the court found tha t the D epartm ent

fails to m aintain adequate records o f incidents of

m isconduct (particularly ones involving racial bias) in

connection w ith perform ance ratings o f individual offi

cers, and tha t it is “ the policy o f the departm ent to

d isc o u ra g e the filing o f such [citizens’] com

plaints . . . and to resist disclosure of the final disposition

of such com plaints.” (App. a t 124a, 357 F. Supp. at

1318). As a result o f its refusal to m aintain records or

process com plaints, the D epartm ent has no m ethod of

identifying officers w ho engage in conduct o f the type

found by the court to be unlawful. Thus, the D epartm ent

is in no position to evaluate or supervise those officers.

6

The trial court determ ined, therefore, th a t the plaintiffs

had made a sufficient showing o f unconstitu tional con

duct by the D epartm ent to w arrant some form o f relief

under 42 U.S.C. §1983.

The court nex t dealt w ith various forms of relief

proposed by the plaintiffs. A fter carefully considering

both the need to p ro tec t the p lain tiffs’ constitutional

rights and the necessity to avoid undue interference w ith

the workings o f the Philadelphia Police D epartm ent, the

trial court rejected the COPPAR p lain tiffs’ request for

the appoin tm ent of a receiver for the D epartm ent. The

court also determ ined th a t detailed injunctive relief was

unnecessary since m any o f the abuses in this case m ight

well be resolved by a consent injunction entered in to by

the same defendants in another case involving similar

issues, Alexander v. Rizzo, (E.D. Pa., C.A. No. 70-992).

The court found tha t a sufficient rem edy for m ost of

the abuses n o t covered by the Alexander decree would be

the institu tion by the Police D epartm ent of a procedure

for handling and m aintaining records o f citizens’ com

plaints against individual police officers. The trial judge

further determ ined th a t such a rem edy w ould be the least

intrusive feasible mechanism which could provide relief

of the sort to which plaintiffs were entitled. Accordingly,

he directed the parties to prepare and subm it a proposed

form of order setting up a program for police handling of

citizens’ com plaints o f police m isconduct. A fter the

parties were unable to agree on an appropriate form of

order, the judge ultim ately entered an order (App. Pet.

Cert. 20a) setting forth detailed procedures for the

handling of citizens’ com plaints by the Philadelphia

Police D epartm ent.4 As entered, the decree tracked the

4The trial court retained jurisdiction to m odify the procedures

upon application of any party in interest.

7

D epartm ent’s proposal in a num ber of m ajor respects as

to the allocation of responsibility for m aintaining and

processing such com plaints.

The defendants then appealed to the C ourt of Appeals

for the Third Circuit, which affirm ed the judgm ent of the

D istrict Court. The C ourt o f Appeals held, inter alia, tha t

there was adequate evidence to support the District

C ourt’s findings of a pattern o f police m isconduct in

violation of 42 U.S.C. §1983; tha t the pattern of

m isconduct was sufficiently substantial to w arrant the

granting of relief; and tha t the order entered by the

D istrict C ourt was an appropriate form o f relief for the

constitu tional violations found.

ARGUMENT

THE DISTRICT COURT’S ORDER WAS BASED ON

ADEQUATE EVIDENCE AND IS AN APPROPRIATE

FORM OF EQUITABLE RELIEF.

A. The Evidence of R ecord Shows a Pattern of

Tolerance o f Police M isconduct for Which Peti

tioners Are Legally Responsible U nder 42 U.S.C.

§1983.

Although the petitioners have never contested the

specific findings of police m isconduct in this case and

although their Brief purports to be lim ited to the

propriety of the D istrict C ourt’s order, Amicus feels

com pelled to address a t the outset w hat appear to be

suggestions woven in to the petitioners’ o ther arguments

tha t there were no findings below of participation by

them in the constitutional violations and that, therefore,

the entry of any relief under 42 U.S.C. §1983 was

im proper. Petitioners’ contentions in this regard both

misstate the lower courts’ findings and m iscom prehend

the law.

8

1. Petitioners’ Responsibility. As the petitioners as

sert th roughout their Brief, they are the officials charged

by law w ith the supervision and control o f the Philadel

phia Police D epartm ent,5 an organization having almost

7,500 individual police officers at the dates involved in

this case.6 The day-to-day conduct of those officers on

the jo b will inevitably reflect their perception of the

desires and expectations o f their superiors. Indeed, as the

com m entators have uniform ly observed, a police depart

m ent is substantially m ore hierarchical in its organization

(resembling in this regard the military) than m ost other

governmental and private organizations.7 U nder these

circumstances, it hardly needs elaborating to say th a t the

expectations o f a superior m ay be com m unicated by

indirect and tacit means as well as by direct and explicit

ones.

The trial court specifically found, on abundant evi

dence, tha t a principal cause o f the instances of police

m isconduct presented in this case was the failure of

superior officers of the Philadelphia Police D epartm ent

(including the Commissioner and D eputy Commissioner

of Police) and their civilian superiors (the M ayor and the

C ity’s Managing D irector)—the petitioners in this case—to

control and supervise the conduct o f individual members

of the Police D epartm ent. In particular, the D istrict

Court found th a t the Police D epartm ent’s systematic

failure to keep records of citizens’ com plaints; dis

5See also the provisions of the Philadelphia Home Rule

Charter, cited at pages 4-5 of petitioners’ Brief.

6The precise figure was 7,439 officers in 1969. See Ruchel-

man, Models o f Police Politics—New York City, Chicago, Philadel

phia, reprin ted in L. Ruchelm an, Who Rules the Police?, at 254

(1973) (hereinafter cited as Ruchelm an).

7See, e.g., Ruchelm an, supra a t 249.

9

couragem ent of the filing of com plaints by citizens

against policemen; failure to investigate com plaints; and

failure to discipline adequately policem en as to whom

citizens’ com plaints have been shown valid,8 all operated

to encourage or acquiesce in a pattern o f m isconduct by

some police officers. The C ourt of Appeals affirm ed these

findings o f the D istrict Court.

Under these circum stances, the petitioners can hardly

dispute th a t they are indeed responsible for the policies

of the D epartm ent, and tha t these policies are responsible

for the pattern of unconstitu tional police activity found

to exist by the lower courts.

2. R elie f Against Petitioners. As a legal m atter, the

propriety of an injunction against a police departm ent for

unconstitu tional action o f its officers due to the failure

of superiors to exercise proper supervision and control

was settled by this C ourt in Allee v. Medrano, 416 U.S.

802 (1974) (injunction against Texas Rangers proper

where officers violate constitu tional rights of citizens).9

See also Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961); Hague v.

CIO, 307 U.S. 496 (1939).

Furtherm ore, it is particularly compelling to regard the

toleration o f constitu tional violations by superior police

officials as calling for relief under 42 U.S.C. §1983

because it is clear tha t one o f the principal reasons for the

enactm ent of Section 1983 was the toleration by state

g

See also Schwartz, Complaints Against the Police: Experi

ence o f the C om m unity R ights Division o f the Philadelphia D istrict

A tto r n e y ’s Office, 118 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1023 (1970).

9Ten courts of appeals had previously reached the same result.

E.g., Sm ith v. Ross, 482 F.2d 33 (6th Cir. 1973); Wright v.

McMann, 460 F.2d 126 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 885

(1972); Schnell v. City o f Chicago, 407 F.2d 1084 (7th Cir. 1969).

10

officials after the Civil War of abuses o f the constitu tional

rights o f blacks. See Monroe v. Pape, supra, 365 U.S.

at 174-77. Indeed, even the dissenters in Allee v.

Medrano, supra, 416 U.S. at 858 n.20, cited w ith

approval a law review article10 which made the po in t

tha t the critical feature of m any police conduct cases was

the toleration o f m isconduct by superior officers, no t

their direct participation therein.

Accordingly, on the evidence o f record, the lower

courts were am ply justified in finding a violation o f 42

U.S.C. §1983 in the petitioners’ system atic failure to

control m isconduct by their subordinates in the Philadel

phia Police D epartm ent, a t least insofar as the propriety

of equitable relief directed a t them is concerned.

B. The Order of the District Court Is a Wholly

Appropriate Remedy for the Violations Found.

In our view, the D istrict C ourt’s order, as affirm ed by

the C ourt of Appeals, is a m odel of restraint. The courts

below, having found a pa tte rn o f violation o f constitu

tional rights by the Philadelphia Police D epartm ent,

fashioned an order which was specifically tailored to the

particular violations and was designed to be as unintrusive

as possible on the legitimate workings of the D epartm ent.

The petitioners now make a num ber of arguments in

support of their contentions tha t the entry o f any

injunctive relief at all, and of the type o f injunctive relief

chosen by the courts below in particular, was im proper.

We deal w ith these contentions seriatim below.

^C o m m en t, The Federal In junction as a R em edy fo r Unconsti

tutional Police C onduct, 78 Yale L .J. 143 (1968).

11

1. The Present Case Presents a Justiciable Contro

versy.

W ithout precisely saying so, petitioners appear to be

claiming tha t the present case does n o t present a

justiciable controversy because the low er courts did no t

hold th a t the D epartm ent’s com plaint review procedure

was in and o f itself unconstitu tional. Petitioners contend

tha t the lower courts have im properly entered a judgm ent

against them based upon a consideration of the “wisdom,

need, desirability or appropriateness” o f the D epart

m en t’s regulations and th a t courts have no pow er to

inquire in to such m atters. Pet. Br. 18-19.

Petitioners’ claims in this regard are plainly incorrect

because they have confused the wrong (unconstitutional

D epartm ent action) w ith the rem edy adopted to cure

it .11 It goes w ithout saying th a t a person seeking

injunctive relief under 42 U.S.C. §1983 need n o t allege

or show th a t he has a constitu tional right to a particular

type o f relief to present a justiciable controversy. R ather

a p lain tiff m ust allege or show tha t he has been or will be

injured by some violation o f his constitu tional rights. As

this C ourt pu t it recently in O ’Shea v. Littleton:

“Plaintiffs in the federal courts ‘m ust allege some

threatened or actual injury resulting from the

putatively illegal action before a federal court m ay

assume jurisd iction .’ ” 414 U.S. 488, 493 (1974).

^ P e titio n e rs ’ confusion on this po in t is som ew hat difficult to

understand since the District C ourt explicitly sta ted th a t its order

was n o t based on a determ ination th a t the D epartm ent’s p roced

ures were constitutionally defective, b u t tha t revision of those

procedures was “a necessary first step in a ttem pting to prevent

future abuses.” A pp. a t 130a, 357 F. Supp. a t 1321.

12

Where a p lain tiff makes the necessary allegations of

injury and then prevails on the m erits by showing

unconstitu tional action on the defendants’ part and

resultant injury, the court is em powered under 42 U.S.C.

§1983 to fashion appropriate relief. Allee v. Medrano,

supra; Schnell v. City o f Chicago, 407 F .2d 1084 (7th

Cir. 1969); Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F .2d 197 (4th Cir.

1966). Such relief is awarded because it is designed to

cure the dem onstrated unconstitu tional actions of the

defendants, no t because the relief itself is constitutionally

required in the absence of proven unconstitutional

conduct.

In the present case, the lower court found “ that

violations of legal and constitu tional rights o f citizens by

the police [departm ent] are . . . widespread . . . .” (App.

at 124a, 357 F. Supp. at 1318). These findings were based

upon fully 47 pages of specific discussion and findings

relating to unlawful action by D epartm ent officers and

injury to the respondents and the class they represent.

(App. 73a-119a.) Accordingly, the lower court entered an

injunction designed to rem edy the constitu tional viola

tions it found and bo th its findings and the relief awarded

were affirm ed by the C ourt of Appeals.

There can thus be no doubt tha t respondents’ initial

allegations, and the findings o f the courts below, show

the presence o f a justiciable controversy in the present

case. Indeed, this is clear from a com parison o f the

present case w ith the authorities cited by petitioners.

For exam ple, petitioners cite Gilligan v. Morgan, 413

U.S. 1 (1973), where this C ourt held nonjusticiable a suit

brought by certain students o f K ent State University

seeking, as a result o f one incident of alleged m isconduct

by the Ohio N ational Guard, an order setting standards

for the training, kind of weapons, and scope and kind of

13

orders to control the actions of the National Guard. N ot

only did the case involve a request for broad relief based

on an isolated incident, b u t it also involved the doctrine

of separation o f powers in th a t the regulation o f the

militia has been expressly entrusted by the C onstitu tion

to the Congress and by it, in part, to the Executive

branch. In contrast, in the present case, no separation of

powers question is involved (indeed, 42 U.S.C. §1983 is

expressly aimed at controlling the conduct of State

officials, such as petitioners) and the injunctive relief

ordered below is based on a continuing pa tte rn of

conduct by the petitioners which has been and remains a

substantial contributing cause o f the violations o f the

constitu tional rights o f respondents and their class.

Petitioners’ reliance on O’Shea v. Littleton, 414 U.S.

488 (1974), is equally misplaced. O ’Shea involved the

propriety o f a com plaint for injunctive relief against

allegedly unconstitu tional conduct by a State magistrate

and a State judge. This C ourt held th a t the plaintiffs

there failed to present a case or controversy in th a t there

were insufficient allegations o f continuing conduct which

was likely to affect the plaintiffs, none o f whom was

“identified as him self having suffered any injury in the

m anner specified.” 414 U.S. a t 495. In the present case,

however, the petitioners have n o t even contested the trial

co u rt’s findings of continuing illegal conduct by the

police which directly im pacts on the respondents’ class

and inadequate contro l o f th a t conduct by petitioners.

The alternative ground o f decision in O ’Shea was simply

an application o f the rule established in Younger v.

Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971), against federal court in terfer

ence w ith S tate criminal prosecutions. Here, o f course, no

14

such interference is p resen t.12 Cf. Doran v. Salem Inn,

Inc., 43 U.S.L.W. 5039 (June 30, 1975); Steffel v.

Thompson, 415 U.S. 452 (1974).

In this case, of course, b o th unconstitu tional conduct

by the police and resulting injury to respondents have

been found by the lower courts, and those findings are

not even contested here. Accordingly, this C ourt’s sta te

m ent in Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1 (1972), with

reference to judicial control o f unconstitu tional conduct

by the m ilitary is of particular applicability to the

unconstitu tional police activity involved in this case:

“ [W jhen presented w ith claims o f judicially cog

nizable injury resulting from m ilitary intrusion in to

the civilian sector, federal courts are fully em

pow ered to consider claims of those asserting such

injury; there is nothing in our N ation ’s history or in

this C ourt’s decided cases, including our holding

today, tha t can properly be seen as giving any

indication tha t actual or th reatened injury by reason

of unlawful activities of the m ilitary w ould go

unnoticed or unrem edied.” 408 U.S. a t 15-16.

1 2Petitioners’ reliance on Hague v. CIO, supra, is som ewhat

m ysterious. Petitioners claim th a t this C ourt’s refusal to perm it a

lower court to save a blatantly unconstitu tional ordinance by

rewriting it should be read as a determ ination tha t m andatory relief

against city officials is generally im proper. What petitioners ignore

is tha t the relief ordered by this C ourt was m ore severe than th a t

ordered by the lower court, nam ely, an injunction against

enforcem ent of the ordinance altogether. In fact, Hague stands as

strong support for the lower cou rts’ decisions here in tha t it

recognizes the propriety of equitable relief against unconstitutional

conduct by city officials such as petitioners.

15

2. Respondents Have No Adequate Rem edy at

Law.

Petitioners claim tha t injunctive relief is inappropriate

here because respondents have an adequate rem edy at

law. This con ten tion is wholly w ithout m erit.

First, 42 U.S.C. §1983 specifically authorizes injunc

tive relief against unconstitu tional official action and

“where . . . there is a persistent pattern o f police m iscon

duct, injunctive relief is appropriate.” AUee v. Medrano,

supra, 416 U.S. at 815 (m ajority opinion), 838 (dissent

ing opinion); Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479,

485-89 (1965); Hague v. CIO, supra. This, o f course, is

precisely such a case.

Second, suits for damages by those subjected to

unconstitu tional conduct by the police will no t suffice to

prevent recurrence o f such m isconduct. For instance, the

offending police officers will generally be judgm ent p roof

and their superiors m ay have a partial im m unity to

damage suits though n o t to injunctive action. See Wood

v. Strickland, 95 S. Ct. 992 (1975); Scheuer v. Rhodes,

416 U.S. 232 (1974). Moreover, as the D istrict C ourt

specifically found here, private damage suits are “ inade

quate” because they

“ are expensive, time-consuming, n o t readily availa

ble, and not notably successfu l. . . .” (App. at 126a,

357 F. Supp. a t 1319.)

This conclusion by the D istrict C ourt is in full agreement

with the views o f Chief Justice Burger:

“ The problem s of bo th error and deliberate m iscon

duct by law enforcem ent officials call for a w orka

ble rem edy. Private damage actions against individ

ual police officers concededly have n o t adequately

m et this requirem ent . . . ."B ivens v. Six Unknown

Fed. Narcotics Agents, 403 U.S. 388, 421 (1971).

16

In sum, respondents and o ther citizens of Philadelphia

are entitled to an effective rem edy against the sort o f

police m isconduct shown here and, contrary to peti

tioners’ contentions, a private action for damages is not

such a remedy. As the lower courts have found here,

only injunctive relief offers any hope o f effectively

protecting the constitu tional rights of citizens from

system atic police abuse.

3. The District Court Was Justified in Ordering

the Department To Improve its Handling o f Citi

zens’ Complaints.

Petitioners nex t claim tha t the federal judiciary is

wholly w ithout pow er to order a municipal police

departm ent to establish adequate internal procedures for

handling citizens’ com plaints about police m isconduct

because the determ ination as to the necessity for such

procedures is “ discretionary” and, therefore, the deci

sions of police officials on this isssue m ust be left to the

judgm ent of the electorate. But petitioners wholly fail to

recognize tha t the Fourteenth A m endm ent, and 42

U.S.C. §1983, were enacted for the specific purpose of

limiting the pow er of elected or appointed officials to

engage in unconstitu tional trea tm ent of citizens. The fact

that a m ajority of voters in a city might possibly approve

of the sort o f police violations o f the C onstitu tion shown

in this case does n o t make the evaluation of police

conduct a political question or preclude an injunction

which requires a police departm ent to m odify its existing

citizen com plaint procedure in order to end a pattern of

unconstitu tional conduct.

Moreover, contrary to the contentions of petitioners

tha t a requirem ent th a t a police departm ent establish

some form of internal review and control of the conduct

of its members is a novel and oppressive concept, it can

17

safely be stated tha t every professional evaluator of

police affairs is in agreement tha t an adequate form of

internal control is a necessity for a properly run police

departm ent. See, e.g., S tandard 5.4, and related com m en

tary at pages 164-67, o f the American Bar A ssociation’s

Standards Relating to the Urban Police Function (1973),

which were unanim ously approved by the Executive

Com m ittee o f the International Association o f Chiefs of

Police in December, 1972; National Advisory Commis

sion on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, Report on

Police, Model Standards fo r Police Internal Discipline,

Standards 19.1-19.6 (1973); The President’s Commission

on Law Enforcem ent and A dm inistration of Justice, The

Challenge o f Crime in a Free Society, at 115-16 (1967),

and Task Force Report: The Police, at 193-97 (1967);

Note, The Administration o f Complaints by Civilians

Against the Police, 77 Harv. L. Rev. 499 (1964).

The reason for this general agreement is bo th straight

forward and exem plified by the facts o f this case. As the

President’s Commission on Law Enforcem ent and Adm in

istration of Justice has stated:

“There is no profession whose members are m ore

frequently tem pted to misbehave, or provided w ith

more opportunities to succumb to tem ptation , than

law enforcem ent. The opportunities arise, on the

whole, from the simple physical fact tha t policemen

generally w ork alone or in pairs, ou t o f sight o f their

colleagues and superiors.” The Challenge o f Crime in

a Free Society, a t 115.

In such a contex t, where the basic constitutional rights

of citizens are at stake, it is particularly im portan t tha t

institutional restraints on official m isconduct exist. When

the absence o f an adequate system o f internal control

can, as here, be shown to have contribu ted to an

18

excessive num ber of instances o f unconstitu tional police

conduct, it is well w ithin the pow er o f a federal court to

require tha t effective internal controls be institu ted .

Indeed, in this connection it is m ost revealing to

com pare the injunction entered by the lower courts w ith

tha t approved by this C ourt in Allee v. Medrano, supra.

Thus, in Allee this C ourt approved an injunction which

prohibited specific acts of m isconduct in the carrying out

of their duties by members o f the Texas Rangers on the

ground tha t such an injunction was necessary to p ro tect

the constititu tional rights of the respondents in tha t case.

This C ourt approved such an injunction even though, to

some exten t, the result was to make the Rangers subject

to possible contem pt proceedings for im proper arrest and

similar decisions in the field. Here, in contrast, the

injunction requires only the prom ulgation and m ainte

nance by high-ranking city officials of a system of

internal police procedures for handling citizens’ com

plaints.

It w ould appear self-evident that, as the lower courts

concluded, an order instructing the Philadelphia Police

D epartm ent to institu te procedures aimed at increasing

its ability to discipline its errant members is a far more

innocuous interference w ith the D epartm ent’s operations

and com m and structure than any o ther type o f order

which could provide the relief the lower courts found

necessary.13

1 3

Since the petitioners have consented to the en try of an

injunction prohibiting the police from certain form s of m isconduct

in Alexander v. R izzo , (E.D. Pa., C.A. No. 70-992), it is possible

th a t they believe, as a m atter o f legal principle, tha t prohibitory

injunctions are preferable to m andatory ones. But see Develop

m ents in the Law —Injunctions, 78 Harv. L. Rev. 994, 1061-63

(1965).

19

4. Petitioners’ Objections to the Precise Form o f

the Trial Court’s Decree Are Wholly Unsupported

by A ny Evidence o f Record.

The petitioners devote six pages o f their Brief (pages

29-35) to a litany of horrible consequences which they

assert will follow from the trial co u rt’s judgm ent in this

case. However, petitioners failed to m ake a. single one of

these objections to either the trial court or the C ourt of

Appeals in this case, and there is no evidence a t all in the

record of this case to support any o f these objections.

Indeed, as the Brief for respondents shows in detail,

m any of the objections which petitioners now assert m ost

vigorously relate to m atters which are either existing

practices of the Philadelphia Police D epartm ent or were

suggested initially to the trial court by petitioners in the

proposed form of order subm itted by them . The im pro

priety of such argum ents by petitioners in this Court

should be readily apparent.

Petitioners are asking this Court to serve, in effect,

as a trial court for the purpose o f making factual

determ inations as to issues wholly outside the record.

Such a role contem plates th a t this Court could approp

riately reverse the decisions of the District Court and

the Court o f Appeals in this case on alleged “ facts”

not of record and on grounds never presented to

either of those courts. This Court has invariably

rejected such attem pts to circumvent its appellate func

tions in the past. E.g., Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391

U.S. 510, 516-18 (1968), and General Motors Corp.

v. Washington, 377 U.S. 436, 449 (1964) (Court will

no t reach claims unsupported by evidence in the reco rd );

Adickes v. S.H. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144, 147 n.2

(1970), and United States v. Spector, 343 U.S. 169, 172

(1952) (Court will not decide issues not raised below

by petitioners). And it should do so again in this case.

20

Furtherm ore, petitioners have totally ignored para

graph 7 of the trial co u rt’s order (App. Pet. Cert, at 23a)

which states “ this C ourt reserves jurisdiction to m odify

this Order and the attached procedures and to grant such

further relief as may be appropriate, upon the application

of any party in in terest.’’ In the event th a t petitioners

seriously believe any o f the specific provisions of the

order entered below would unduly interfere w ith the

operations of the Philadelphia Police D epartm ent, they

will be at liberty , after an affirm ance by this Court, to

seek a m odification of those procedures from the D istrict

judge in a proceeding in which their objections m ay be

fully explored and appropriately resolved.14

Finally, petitioners’ predictions of adverse conse

quences from the procedures established by the trial

co u rt’s order are purely speculative and, in fact, contrary

to the judgm ent o f m ost professional police adm inistra

tors. For example, in the Model Standards for Police

Internal Discipline prom ulgated by the National Advisory

Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, it

is stated tha t “ the chief executive o f every police agency

im mediately should insure tha t the investigation o f all

com plaints from the public, and all allegations of criminal

conduct and serious internal m isconduct, are conducted

by a specialized individual or un it of the involved police

14In this connection, the trial court has already recognized the

need to minimize interference w ith the day-to-day operations of

the Police D epartm ent.

“ [D ] eference to the essential role o f the police in our

society does m andate th a t intrusion by the courts into this

sensitive area should be limited, and should be directed

tow ard insuring tha t the police themselves are encouraged

to rem edy the situation .” App. a t 127a, 357 F. Supp. at

1320.

21

agency.” Standard 19.3. Similarly, S tandard 19.5(3)

provides that: “An adm inistrative factfinding trial board

should be available to all police agencies to assist in the

adjudication phase.” Indeed, as the authorities cited at

page 17, supra, uniform ly recognize, there is no serious

disagreement among police professionals (o ther than

petitioners) w ith the proposition th a t any properly run

Police D epartm ent should have an effective internal

mechanism, such as th a t required by the trial c o u rt’s

order in this case, for investigating and adjudicating

claims of m isconduct by police officers.

CONCLUSION

As the foregoing discussion dem onstrates, the tw o

lower courts found, on abundant evidence, tha t the

petitioners herein are responsible for a continuing pattern

of unconstitu tional conduct by the Philadelphia Police

D epartm ent. Taking careful consideration o f the neces

sity for minimal interference w ith Police D epartm ent

procedures, the lower courts entered an injunction which

they found to be the least intrusive relief which could

potentially rem edy the violations found. The petitioners’

legal arguments concerning the lower courts’ asserted lack

of pow er to order the D epartm ent to improve its

22

procedures for handling citizens’ com plaints of police

m isconduct are w ithout m erit and their objections to the

specifics of the order are w ithout foundation in the

record. Accordingly, the lower courts’ decisions should

be affirm ed by this Court.

Respectfully subm itted,

Peter Van N. Lockwood

Caplin & Drysdale

1 101 - 17th Street, N.VV.

Washington, D.C. 20036

David Bonderman

Arnold & Porter

1229 - 19th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Attorneys fo r Amicus Curiae.

O f Counsel:

J. Harold Flannery

Paul R. Dimond

William E. Caldwell

Norman J. Chachkin

520 Woodward Building

Washington, D.C. 20005

Ju ly , 1975

' V