Legal Defense Fund Intervenes on Behalf of 4,000 Watts Rioters

Press Release

October 8, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 3. Legal Defense Fund Intervenes on Behalf of 4,000 Watts Rioters, 1965. a361084d-b692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9674c9d7-b49c-4c98-9bab-ac95d84beae9/legal-defense-fund-intervenes-on-behalf-of-4-000-watts-rioters. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

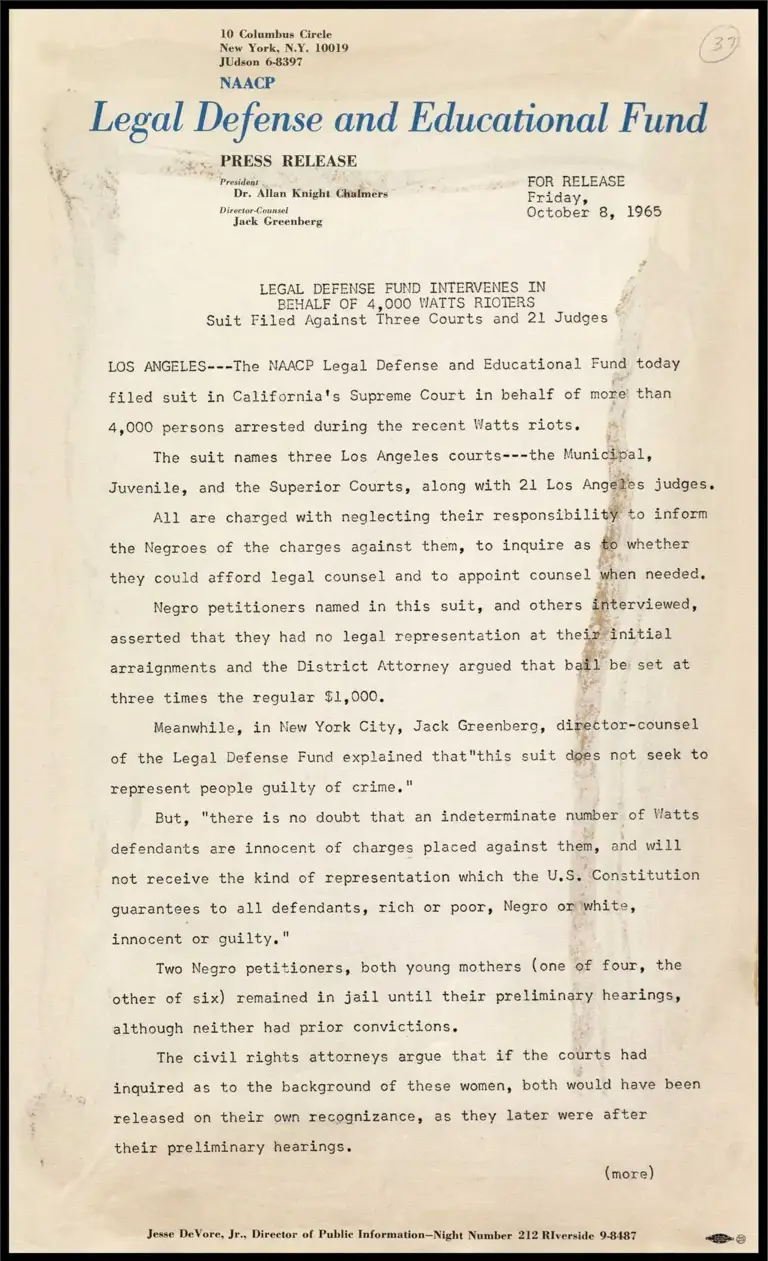

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

JUdson 6-8397

NAACP

Legal ee and Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE

“President

:

Dr. Allan Knight Chalmers ie eee a

aYs

Director-Counse

a jack Gresabery October 8, 1965

LEGAL DEFENSE FUND INTERVENES IN

BEHALF OF 4,000 WATTS RIOTERS

Suit Filed Against Three Courts and 21 Judges

LOS ANGELES---The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund today

filed suit in California's Supreme Court in behalf of more’ than

4,000 persons arrested during the recent Watts riots.

The suit names three Los Angeles courts---the Municipal,

Juvenile, and the Superior Courts, along with 21 Los Angekes judges.

All are charged with neglecting their responsibility to inform

the Negroes of the charges against them, to inquire as fo whether

they could afford legal counsel and to appoint counsel when needed.

Negro petitioners named in this suit, and others interviewed,

asserted that they had no legal representation at theiz initial

arraignments and the District Attorney argued that pail be; set at

three times the regular $1,000.

Meanwhile, in New York City, Jack Greenberg, director-counsel

of the Legal Defense Fund explained that"this suit dies not seek to

represent people guilty of crime."

But, "there is no doubt that an indeterminate number of Watts

defendants are innocent of charges placed against them, and will

not receive the kind of representation which the U.S. Constitution

guarantees to all defendants, rich or poor, Negro or white,

innocent or guilty."

Two Negro petitioners, both young mothers (one of four, the

other of six) remained in jail until their preliminary hearings,

although neither had prior convictions.

The civil rights attorneys argue that if the courts had

inquired as to the background of these women, both would have been

released on their own recognizance, as they later were after

their preliminary hearings.

(more)

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Information—Night Number 212 Riverside 9-8487 So

Legal Defense Fund Intervenes In-2-

Behalf of 4,000 Watts Rioters

More specifically, the suit states that the judicial

officials cited “have failed and refused to appoint private

counsel not associated with the Public Defender's office."

It was noted that the Public Defender's staff had not beens

expanded sufficiently to "give adequate time for preparation ani ¥

investigation to defend petitioners." hae s

The suit further asserts that "none of the petitionses has

been continuously represented by one Public Defender through

successive proceedings, resulting in each Public Defender having

to freshly acquaint himself with the cases."

Moreover, “the Public Defender's office has never been

required to handle over 4,000 defendants with multiple charges

during a six week period such as occurred after the riots began.

Legal Defense Fund Assistant Counsel Leroy Clark, joined by |

aed

local NAACP attorneys Raymond L, Johnson and Herman T. Smith,

pointed out that lists of attorneys willing to represent indigent

persons were given to judicial officials cited in the sui

However, the officials still failed to appoint private lawyers

from this list in sufficient number to relieve the over-extended

case load of the Public Defender's office. re

The Legal Defense Fund, which entered the case upon request

of the local NAACP chapter, filed the case in California's Supreme

Court rather than a lower court "because it is a mathesvor grave

public importance and raises serious questions of constitutionality

and authority of respondent officials to continue with criminal

prosecutions of over 4,000 persons," according to Mr, Clark.

The civil rights attorneys ask that the courts:

1. appoint lawyers with adequate preparation, investigation

and counseling before conducting further proceedings

2. nullify any prior proceedings in which petitioners or

members of their class, after securing adequate counsel,

can demonstrate that they were disadvantaged by lack of

counsel

3. furnish petitioners with names of private counsel if the

Public Defender's office is found to have an inordinate

case load (and to pay such attorneys) (more)

Legal Defense Fund Intervenes In-3-

Behalf of 4,000 Watts Rioters

And, in the alternative, the civil rights lawyers ask that

the cited courts be enjoined from taking further proceedings until

there is a hearing.

-30-

EDITOR'S NOTE: *Complete text of Mr. Greenberg's statement is

rF attached,

*"The "NAACP Legal Defense Fund" is not ithe NAACP,

The two were separated in 1939 and now-function

in close cooperation as two separate entities,