St. Peter v Alexander Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 11, 1980

16 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. St. Peter v Alexander Brief Amicus Curiae, 1980. 5da83786-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96813a16-c396-466c-b0d2-d8532bb84d88/st-peter-v-alexander-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

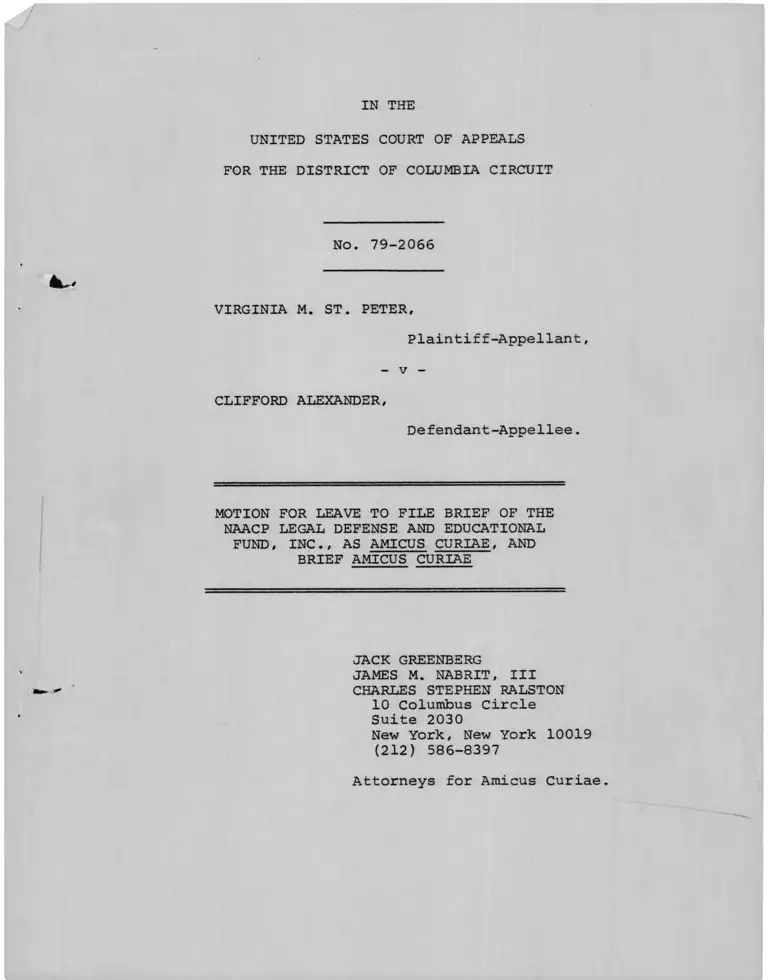

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 79-2066

VIRGINIA M. ST. PETER,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

- v -

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER,

Defendant-Appellee.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF OF THE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE, AND

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae.

INDEX

Page

Motion For Leave To File Brief

Amicus Curiae ....................... 1

Argument:

The District Court Failed To Follow

Properly The Decisions Of The Supreme

Court In McDonnell Douglas v. Green

and Furnco Construction Co. v. Waters 1

Conclusion .............................. 9

Certificate of Service ................. 10

Table of Cases

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972) 6

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Authority, 429 U.S. 252 (1977) 6

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) 6

Davis v. Califano, ___F.2d ___, 21 F.E.P.

Cases 272 (D.C. Cir. 1979) 8

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977) 5

Furnco Construction Co. v. Waters, 438

U.S. 567 (1978) passim

Page

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971) ............................

McDonnel Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411

U.S. 792 (1973) .................

Olson v. Philco-Ford, 531 F.2d 474

(10th Cir. 1974) ................

Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts

v. Feeney, U.S. , 600

L. Ed. 2d 870 (1979) ............

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324

(1977) ...........................

4

passim

5

8

2, 3

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 79-2066

VIRGINIA M. ST. PETER,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

- v -

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER,

Defendant-Appellee.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE ON BEHALF OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Movant NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., respectfully move^ the Court, pursuant to Rule 29 F.R.A.

Proc., for permission to file the attached brief amicus curiae,

for the following reasons. ( The reasons assigned also disclose

the interest of the amicus.

(1) Movant NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a non-profit corporation, incorporated

under the laws of the State of New York in 1939.

It was formed to assist Blacks to secure their

constitutional rights by the prosecution of lawsuits.

Its charter declares that its purposes include render

ing legal aid gratuitously to Blacks suffering in

justice by reason of race who are unable, on account

or poverty, to employ legal counsel on their own

behalf. The charter was approved by a New York

Court, authorizing the organization to serve as a

legal aid society. The NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF), is independent of

other organizations and is supported by contributions

from the public. For many years its attorneys have

represented parties and has participated as amicus

curiae in the federal courts in cases involving many

facets of the law.

(2) Attorneys employed by movant have represented plaintiffs

in many cases arising under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 in both individual cases, e .g .,

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973);

Furnco Constitution Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567

(1978); and in class actions, e.g., Albermarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Franks v. Bowman

Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976). They have

appeared before this Court in a variety of Title VII

cases involving agencies of the federal government

both as counsel for plaintiffs, e.g., Foster v.

Boorstin, 561 F.2d 340 (D.C. Cir. 1977), and as

2

amicus curiae, Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d

108 (D.C. Cir. 1975); Davis v. Califano, ____

F - 2d ______ , 21 F.R.P. Cases 272 (D.C. Cir.1979).

(3) Through their extensive participation in Title VII

cases, attorneys for amicus have acquired substantial

expertise in issues concerning the burden of proof

and the application of the standards for deciding

individual Title VII class actions, the issues in

the present case addressed by the attached brief.

Therefore, we believe that our views on the

important questions before the Court will be help

ful in their resolution.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons we move that the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. be given leave

to file the attached brief amicus curiae.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

3

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 79-2066

VIRGINIA M. ST. PETER,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-v-

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER,

Defendant-Appellee.

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

ARGUMENT

The District Court Failed to Follow Properly The

Decisions of the Supreme Court in McDonnell Douglas

v. Green and Furnco Construction Co. v. Waters.

As indicated in the motion of leave to file this

Brief, the Legal Defense Fund is concerned that the proper

legal standards be applied to the decision of Title VII cases,

whether individual or class action, so that the district courts

are consistent in their treatment of these important cases.

Only in this way will Title VII continue to be a meaningful

remedy against employment discrimination. Simply put, the

decision of the district court in the present case, if allowed

to stand, would emasculate Title VII by erecting an absolute

defense in virtually all hiring or promotion cases. Moreover,

the decision fails to properly apply the standards developed

by the Supreme Court in McDonnell Douglas Corp, v. Green, 411

U.S. 792 (1973), and Furnco Construction Company v. Waters,

438 U.S. 567 (1978), by which employment discrimination cases

are to be decided.

Although the district court cited McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v. Green, it totally failed to apply that case properly

by confusing the making of a prima facie case of discrimination

with what constitutes a valid rebuttal to such a case. McDonnell

Douglas established basic principles for deciding an individual

case of discrimination in a Title VII case involving a claim of

disparate treatment, as opposed to disparate impact. As explained

by the Court in Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 335,

n.15 (1977), a disparate treatment case requires proof of dis-

1/criminatory motive, while a disparate impact case does not.

1/ 'Disparate treatment* * such as alleged in the present

case is the most easily understood type of discrimina

tion. The employer simply treats some people less

favorably than others because of their race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin. Proof of discrimi

natory motive is critical, although it can in some

situations be inferred from the mere fact of differences

in treatment. See, e.g., Village of Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp. 429 U.S. 252, 265-

266.

* * * *

Claims of disparate treatment may be distinguished

from claims that stress 'disparate impact.' The latter

involve employment practices that are facially neutral

in their treatment of different groups but that in fact

2

The Court has also made clear, however, that a finding of a

discriminatory motive does not require evidence of overt or

subjective racism or sexism. Rather, it can be based on

objective evidence from which an inference of discrimination

2/

may be drawn.

McDonnell Douglas used these principles to establish

a method for analyzing individual disparate treatment cases.

First, the plaintiff has the burden of establishing a prima

facie case of discrimination. Second, the burden then shifts

to the employer to prove "that he based his employment decision

on a legitimate consideration, and not an illegitimate one such

as race " (Furnco Constrution Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. at 577),

or, in other words, the employer must "articulate some legitimate,

nondiscriminatory reason for the . . . rejection " (McDonnell

Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. at 802). Third, if this burden is

met, the plaintiff then has the opportunity to show that the

1/ (cont'd)

fall more harshly on one group than another and cannot

be justified by business necessity. Proof of discri

minatory motive, we have held, is not required under

a disparate impact theory. Compare, e.g., Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, with McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 802-806.

2/ As the Supreme Court said in Teamsters:

Although the McDonnell Douglas formula does not

require direct proof of discrimination,it does demand

that the alleged discriminatee demonstrate at least

that his rejection did not result from the two most

common legitimate reasons on which an employer might

rely to reject a job applicant: an absolute or relative

lack of qualifications or the absence of a vacancy in

3

proffered reason is a pretext for discrimination.

McDonnell Douglas further articulated the elements

of a prima facie case in the context of the facts of that

37hiring case. The plaintiff must show that: (1) he belongs

to a minority; (2) he applied for an available job for which

he was qualified; (3) he was rejected; and (4) the position

remained open and the employer continued to seek applicants.

The present case is basically a disparate treatment

4/

case, and therefore should be analyzed under McDonnell Douglas

-Furnco standards. As noted in Teamsters, the plaintiff was

required only to show that there was a position for which she

2/ (cont'd)

The job sought. Elimination of these reasons for

the refusal to hire is sufficient, absent other

explanation, to create an inference that the

decision was discriminatory.

431 U.S. at 458, n.44.

3/ The Court was careful to point out that:

The facts necessarily will vary in Title VII

cases, and the specification above of the

prima facie proof required ... is not necessarily

applicable in every respect to differing factual

situations.

411 U.S. at 802, n.13.

4/ Teamsters notes that either a disparate treatment or

disparate impact theory "may ... be applied to a particular

set of facts." 431 U.S. 335 n.15. The present case has

elements of a disparate impact case. The original requirement

that the selectee be a West Point graduate would clearly have

had a disparate impact on women, making the case like Griggs

v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) and Dothard v. Rawlinson,

4

applied, and that she had the basic qualifications necessary

for the job and was not less qualified than the male selectee,

i.e., that there was not "an absolute or relative lack of

5/

qualifications" (431 U.S. 358, n.44). Put in McDonnell

Douglas terms, once plaintiff showed that: (1) she belonged

to a protected class; (2) she applied and was qualified for

an available job; (3) she was rejected; and (4) a male was

chosen, the burden to come forward with a legitimate, nondis-

criminatory reason shifted to defendant. Indeed, plaintiff

did more than required, since she demonstrated, and the dis

trict court so held, that she was more qualified than the

male selected.

Thus, the district court was in clear error when it

held that a prima facie case had not been made. As a result

it failed to apply the proper standard for evaluating the

defendant's explanation for its action. As stated in Furnco

4/ (cont'd)

433 U.S. 321 (1977). Moreover, the selecting officials'

criteria that the selectee be "clean-cut" and be able to

deal with Congressmen "buddy-to-buddy" would necessarily

favor men over women.

5/ Thus, the holding of the decision relied upon by the

Court below, Olson v. Philco-Ford, 531 F.2d 474 (10th Cir.

1974),holding that it is not enough for the woman to show that

she was equally qualified as the male selectee is inconsistent

with McDonnell Douglas as explained by Teamsters.

5

there must be "proof of a justification which is reasonably-

related to the achievement of some legitimate goal." 438 U.S.

6/

at 578. The employer-defendant here totally failed to meet

this burden. The district court itself found that there was

a failure to follow proper procedures and that "the selection

process . . . resembled nothing so much as the game of "enie,

meenie, minie, moe; with the results being of about that qua

lity." Certainly, the arbitrary selection of the least quali

fied person for an important position can hardly be related to

any "legitimate goal" of an employer.

The district court's failure to apply a proper

McDonnell Douglas analysis led it to a number of incorrect

conclusions. First, it failed to recognize that a failure to

follow proper procedures and a bad substantive result are in

themselves indicia of discriminatory intent. See, Arlington

6/ The test for evaluating the sufficiency of a rebuttal of a

prima facie case has been stated in a variety of contexts.

Thus, in jury discrimination cases it must be shown that "per

missible racially neutral selection criteria and procedures" have

been used. Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625, 632 (1972)

(emphasis added), or by "evidence in the record about the way

in which the commissioners operated and their reasons for

doing so." Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 500 (1977).

However phrased, it is clear that the reasons must be permis

sible and legitimate hs well as nondiscriminatory.

6

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Authority, 429 U.S. 252,,267

(1977), Thus, such factors necessarily cannot rebut a prima

facie case.

Second, and most important, the reasoning that

because some males ware also adversely affected by the defend

ant's arbitrariness, there was no discrimination, would completely

destroy the effectiveness of Title VII. In virtually all hiring

or promotion situations, particularly in the federal government,

white males in addition to the one selected apply for positions.

Under the logic of the district court, in every one of those

cases there would be an absolute defense to a charge of discri

mination since there would be some white males denied the job

along with women or racial minorities. The problem with the

district court's approach is that it failed to focus on the

rights of the members of the protected class. While it is true

that the two white males denied the job were not discriminated

7 / “Departures from the normal procedural sequence also

might afford evidence that improper purposes are

playing a role. Substantive departures too may

be relevant^ particularly if the factors usually

considered important by the decision maker

strongly favor a decision contrary to the one

reached." Ibid.

7

against because of their sex, that in no way leads to the

9/

conclusion that the woman was not.

Finally, the district court's conclusion that there

was nothing wrong with the use of subjective criteria in this

case is completely inconsistent with the recent decision of

this Court in Davis v. Califano, ___ F.2d ____ , 21 F.E.P.

8/

Cases 272, 279 (D.C. Cir. 1979). There, this Court noted that

the employer's:

... promotion procedures are highly suspect and must

be closely scrutinized because of their capacity for

masking unlawful bias. The "lack of meaningful

8/ Another aspect of the case that was overlooked by the dis

trict court indicates that there may indeed have been a discri

minatory reason for the failure to give proper consideration

to one of the highly qualified males. As brought out during

the trial, the original position announcement specified that

the person to fill the position should be a West Point graduate

under 40 years of age. Because those requirements were recog

nized by the Personnel Department to be discriminatory on the

grounds of both sex and age, they were struck from the announce

ment itself. However, the person selected for the position was,

in fact, a male under the age of 40. Ms. St. Peter and one of

the male applicants were both over 40. Thus, it is possible

that his non-selection was also based on a reason that was not

non-discriminatory, and that therefore could not be the basis

for a rebuttal of a prima facie case of discrimination. The

other male applicant testified that he did not have a strong

interest in the position in question.

9/ The district court's reliance in Personnel Administrator of

Massachusetts v. Feeney, U.S. , 60 L.Ed.2d 870 (1979),

is completely misplaced. That case in no way purports to hold

that the simple fact that some whites or males have been adverse

ly affected by an employment practice along with blacks or women

means that there can be no discriminatory intent. To give the

clearest example, if an employee deliberately adopted a college

degree requirement knowing it would prevent a great number of

blacks from obtaining a job, it would be no defense to a Title

VII case to show that some whites were also eliminated.

8

standards to guide the promotion decision,

whereby there is some assurance of objec

tivity ... encourage[s] and foster[s]

discrimination."

Ibid. As the Supreme Court held in McDonnell Douglas, the

overriding purpose of Title VII is:

efficient and trustworthy workmanship

assured through fair and [sexually] neutral

employment personnel decisions. In the

implementation of such decisions, it is

abundantly clear that Title VII tolerates

no ... discrimination [based on sex], subtle

or otherwise.

411 U.S. at 801. The net result of the decision below is to

tolerate discrimination by permitting arbitrary, standardless,

and manifestly unfair personnel decisions that can mask unlawful

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the

bias.

Conclusion

district court should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

9

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have served copies

of the foregoing Brief Amicus Curiae by depositing

copies of the same in the United States mail, first

class postage prepaid, addressed 'to counsel for the

appellant and appellee as follows:

February j

Ronda L. Billig, Esq.

Mark T. Wilson, Esq.

2210 R. Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20008

John A. Terry, Esq.

Assistant United States Attorney

3rd. & Constitution Avenue

Washington, D.C. 20001

1980