Brief for Appellant -- Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City County

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1967

20 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Green v. New Kent County School Board Working files. Brief for Appellant -- Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City County, 1967. a79417f4-6c31-f011-8c4e-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96a76eca-fcef-4694-9cd4-830217376960/brief-for-appellant-bowman-v-county-school-board-of-charles-city-county. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

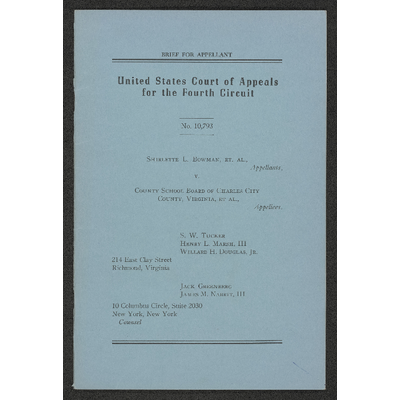

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 10,793

SHIRLETTE L. BowMAN, ET. AL.

Appellants,

V.

County ScHO00L BoArD oF CHARLES CITY

CouNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL.,

Appellees.

SW. TUCKER

HexNry L. Marsh, 111

WiLrLarp H. DoucLas, Jr.

214 East Clay Street :

Richmond, Virginia

JAck GREENBERG

James M. Nasgrir, 111

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York

Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

STATEMENT OR TRE CIABR 0 Es 1

TaE QUESTIONS INVOLVED

SramseENr or HME FACTS | 0 a i 3

ARGUMENT

I. The Court Must Enjoin The School Board’s Operation Of

Separate Schools For Negro, White And Indian Pupils

II. The Faculties Should Be Desegregated Immediately

III. The Reluctance Of The Individual Teachers To Transfer To

A School Staffed With Teachers Of The Opposite Race Can-

not Be Permitted To Defeat The Right Of The Plaintiffs

That Teachers Be Assigned On A Non-Racial Basis

ONCLUSION 12

TABLE OF CASES

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965)

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1935)

Buckner v. Greene County, 332 F. 2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964)

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)

Dowell v. Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W. D. Okla. 1965) .... 8

Kier v. Augusta County, 249 F. Supp. 239 (W. D. Va. 1966)

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965)

Wheeler v. Durham, . (4th Cir. July 5, 1966)

Wright v. Greensville, 252 F. Supp. 378 (E.D. Va. 1966)

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No: 10,793

SHIRLETTE L. BowMAN, ET AL.,

Appellants,

Vv.

County ScHOoOL Board oF CHARLES CITY

CouUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL.,

Appellees.

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The complaint filed on March 15, 1965, prayed, inter alia,

that the defendants be required to bring in a plan requiring

the prompt and efficient elimination of racial segregation

in the county schools, including the elimination of any and

all forms of racial discrimination with respect to adminis-

trative personnel, teachers, clerical, custodial and other em-

ployees, transportation and other facilities, and the assign-

ment of pupils to schools and classrooms. (A. 1)

On May 10, 1966, the school board filed its plan for school

desegregation and on June 9, the plaintiffs filed their ex-

|

|

|

i

¥

|

'

|

| j

J

2

ceptions to said plan. (A. 24) On May 17, the District

Court ordered the defendants to amend their plan to pro-

vide for allocation of faculty on a non-racial basis. (A. 20)

After a hearing on June 10, 1966, the District Court de-

clined to accept the defendants’ amended plan. (A. 27)

The defendants filed the second amendment to their de-

segregation plan on June 30, 1966. (A. 33) On July 27th,

the plaintiffs filed their notice of appeal challenging the

July 15, 1966 order which approved the defendants’ plan.

(A. 36)

THE QUESTIONS INVOLVED

I

Where Separate Schools Are Staffed And Operated For

Negro, White, And Indian Pupils, And No Administrative

Obstacles Are Shown To Justify Any Further Delay In The

Immediate Desegregation Of The System, Can The School

Board Discharge Its Obligation To Dis-establish Its Segre-

gated System By Adopting A Freedom Of Choice Plan,

Where Such Plan Is Demonstrated To Be The Least Likely

Means To Accomplish Meaningful Desegregation?

II

In The Absence Of Administrative Obstacles To Justify

Any Further Delay, Should The Faculties Of The County’s

Four Schools Be Desegregated Immediately?

ITI

Can The Reluctance Of The Individual Teachers To

Transfer To A School Staffed With Teachers Of The Oppo-

site Race Defeat The Right Of The Plaintiffs That The

Teachers Be Assigned On A Non-Racial Basis?

3

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Charles City County is a rural county in Eastern Vir-

ginia. The county school system accommodates approxi-

mately 1,800 pupils, of which 1,300 are Negroes, 300 are

white and 200 are Indians.

For the 1964-65 session, eight (8) Negro children were

assigned to grades 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11 at the formerly

all-white Charles City High and Elementary School. Other-

wise, the facts and figures shown in the following tables pic-

ture the school system of Charles City County as of the close

of that term:

Race of Planned Estimated

School Grades Pupils Capacity Enrollment

Ruthville 1-12 Negro 832 830

Barnetts 1-7 Negro 600 560

Charles City 1-12 White 250 255

Samaria 1-12 Indian 212 175

Totals 1894 1820

Average Teaching Pupil- Average

Trans- Personnel Teacher Class

School ported By Race Ratio Size

Ruthville 1985 35 Negro 25 27.3

Barnetts : 23 Negro 25.5 28

Charles City 195 16 White 17 18

Samaria 145 8 Indian 16.5 18

3 White —

—- 22.4

Totals 85

“The Negro elementary schools serve geographical areas.

The other schools serve the entire county.” (A. 19) Home

Economics, Vocational Agriculture, Shop and General Me-

chanics are offered only at the all-Negro Ruthville High

|

|

|

l

|

|

i

i

i

!

|

4

School. Academic, commercial and general high school sub-

jects are offered in each high school. However, the commer-

cial teacher at Samaria (Indian) School had but 36 pupils;

the commercial teacher at Charles City (white) School had

but 45 pupils; and their counterpart at Ruthville (Negro)

School had 135 pupils.

The bus routes demonstrate that Negroes and whites live

in all sections of Charles City County. The buses transport-

ing the Indian pupils to the Indian School travel some of the

same routes utilized by the other buses. (See plaintiff ex-

hibits numbers C, D, E, and F.)

Prior to and during the 1964-65 school year, the county

operated under the Virginia Pupil Placement Act, §§ 22-

232.1 et seq., Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended.

In executing its power or purported power of enrollment

or placement of pupils in and determination of school dis-

tricts for the public schools of the county, the Pupil Place-

ment Board followed or approved the recommendations of

the county school board, except that the Pupil Placement

Board would refuse to deny the application of a Negro

parent for the assignment of his child to a white school and

would refuse to deny the application of a white parent for

the assignment of his child to a Negro school. (Complaint,

paragraph 10 and Answer, paragraph 7.) :

On August 6, 1965, the county school board adopted a

freedom of choice plan to comply with Title VI of the 1964

Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000.d-1, et seq. The first

registration under the plan was scheduled for the spring of

1966.

The plan provides in part as follows:

“VI. OVERCROWDING

“A. No choice will be denied for any reason other

than overcrowding. Where a school would become over-

5

crowded if all choices for that school were granted,

pupils choosing that school will be assigned so that they

may attend the school of their choice nearest to their

homes. No preference will be given for prior attend-

ance at the school.

“B. The Board does not anticipate overcrowding. All

requests have been granted during the past three years.

(The Board will make provisions to take care of all

requests for transfers. )”

Letters to parents implementing the plan provide in part

as follows:

“The desegregation plan provides that each pupil

and his parent or guardian has the absolute right to

choose each year the school the pupil will attend. * * *

“Attached is a Choice of School Form listing the

names and locations of all schools in our system and the

grades they include. Please mark a cross beside the

school you choose, and return the form in the enclosed

envelope or bring it to any school or the Superinten-

dent’s office by May 31, 1966.

“No choice will be denied for any reason other than

overcrowding. Any one whose choice is denied because

of overcrowding will be offered his choice from among

all other schools in the system where space is available

in his grade.

* * *

“For pupils entering grades one (1) and eight (8) a

Choice of School Form must be filled out as a require-

ment for enrollment. Children in other grades for

whom no choice is made will be assigned to the school

they are presently attending.”

The principal at Charles City (white) was employed in

1960. Since that date only 8 of the 16 professional positions

in that school have been filled by initial employment; 2 in

|

|

i

|

6

1963, 4 in 1964, 1 in 1965, and 1 for the 1966-67 school

session.

The principal at Samaria (Indian) School was employed

in 1961. Since 1960 only 4 of the 11 professional positions

in that school have been filled through initial employment;

1 in 1962, 1 in 1963 and 2 in 1964.

The principal at Ruthville (Negro) School was em-

ployed in 1945. Since 1960 only 12 of the 35 professional

positions in that school have been filled through initial em-

ployment; 4 in 1962, 2 in 1963, and 6 in 1964.

The principal at Barnetts Elementary (Negro) School

was employed in 1946. Since 1960 only 2 of the 23 pro-

{essional positions in that school have been filled by initial

employment; both in 1964.

As of June 30, 1966 the school board had sought and

failed to secure white teachers for the 9 position vacancies

then existing in the two last named Negro schools and had

assigned one Negro to teach in the predominantly white

Charles City School.

Prior to March 15, 1965, several Negro citizens filed peti-

tions with the school board asking the school board to end

racial segregation in the public school system and urging the

Board to make announcement of its purpose to do so at its

next regular meeting and promptly thereafter to adopt and

publish a plan by which racial discrimination will be termi-

nated with respect to administrative personnel, teachers,

clerical, custodial and other employees, transportation and

other facilities, and the assignment of pupils to schools and

classrooms.

On March 15, 1965, several of the plaintiffs filed this ac-

tion in the District Court.

7

ARGUMENT

I

The Court Must Enjoin The School Board’s Operation of Separate

Schools for Negro, White and Indian Pupils

This record reveals the remarkable spectacle of a school

board, more than 11 years after the 1954 Brown decision,

operating what is in effect three distinct school systems—

each organized along racial lines—with hardly enough

pupils for one system! The sacrifice of recognized educa-

tional principles to maintain the segregated character of the

schools is apparent from a comparison of the average class

sizes and the pupil-teacher ratios (see chart on page 3) and

from the operation of three separate high school depart-

ments serving a combined total of approximately 600 pupils,

437 of which are in one school.

The thousands of children—Negro, white and Indian—

who have graduated from the Charles City County Schools

since 1954 could read about the Brown decision in their

classes or discover the changes it had wrought in other com-

munities from the various media, but they could never ex-

perience in their school life a tangible reason to believe that

our Constitution is color blind or that it is the supreme law

of the land.

The petition and accompanying letter from Negro citi-

zens of Charles City County had pointed out to the school

board its clear duty to desegregate the County’s schools.

When this petition was ignored, this litigation was instituted.

The school board sought to avoid its duty to disestablish

the ‘triple’ school system it had created, by adopting during

the pendency of the suit, a so called “freedom of choice”

plan.

It is obvious from the history of this case that the school

board’s plan will not operate to desegregate the schools in

Charles City County. Under the Pupil Placement Board

8

procedure, the parents of white, Negro and Indian pupils

had been afforded an unrestricted choice between having

their children attend white, Negro or Indian schools. Since

1956, however, only a handful of pupils had ever attended

school with members of another race. Notwithstanding the

apparent ease with which the system could be desegregated

by the adoption of a geographical zoning plan, the board se-

lected the means least likely to bring about the desegregation

of the schools in Charles City County. Cf. Dowell v. Okla-

homa City, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965).

When the school board failed to show any administrative

obstacles which would justify a delay in the immediate total

desegregation of its school system, the Court was obligated

to require a plan which would forthwith accomplish the

total desegregation of the school system. Buckner v. Greene

County, 332 F. 2d 452, (4th Cir. 1964); Kier v. Augusta

County, 248 F. Supp. 239, (W.D. Va, 1966).

I

The Faculties Should Be Desegregated Immediately

One thing obviously essential to elimination of racial

segregation from the Charles City County School system is

the desegregation of the teaching staffs of the two schools.

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103, (1965) ; Rogers v.

Poul, 382 11.8, 193, (1965) Wheeler v. Durham, .. F. 2d

...., (4th Cir. July 3, 1966) ; Kier v. Augusta County, 249 F.

Supp. 239, (W.D. Va. 1966) and Wright v. Greensville, 252

P. Supp. 378, (E.D. Va, 1966).

In Kier v. Augusta County, supra, the District Court, after

enjoining the board to desegregate the faculties and admini-

strative staffs completely for the following (1965-66) school

year, stated:

g

“Some guideline must be established for the School

Board in carrying out the Court’s mandate. Insofar as

possible, the percentage of Negro teachers in each

school in the system should approximate the percentage

of the Negro teachers in the entire system for the 1965-

66 school session. Such a guideline can not be rigorously

adhered to, of course, but the existence of some stand-

ard is necessary in order for the Court to evaluate the

sufficiency of the steps taken by the school authorities

pursuant to the Court’s order. A similar standard was

adopted by the District Court in deciding the school de-

segregation suit involving Oklahoma City. Dowell v.

School Bd., 244 F. Supp. 971, 977-78 (W.D. Okla.

1065).

In Wright v. Greensville County, supra, adopted as the

opinion in this case, the Court, after indicating that the

School Board had to provide for the elimination of racially

segregated faculties, set forth the following standard to be

applied by the School Board in desegregating the teaching

staffs:

“Token assignments will not suffice. The elimination

of a racial basis for the employment and assignment of

staff must be achieved at the earliest practicable date.

The plan must contain well defined procedures which

will be put into effect on definite dates.”

In the face of these admonitions, the defendants filed with

the Court a plan, the material parts of which are:

“1. The best person will be sought for each position

without regard to race, and the Board will follow the

policy of assigning new personnel in a manner that

will work toward the desegregation of faculties.”

* * *

“3. The School Board will take affirmative steps in-

cluding personal conferences with members of the pres-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10

ent faculty to allow and encourage teachers presently

employed to accept transfers to schools in which the

majority of the faculty members are of a race different

from that of the teacher to be transferred.”

“4. No new teacher will be hereafter employed who

is not willing to accept assignment to a desegregated

faculty or in a desegregated school.”

* * *%

“10. Arrangements will be made for teachers of one

race to visit and observe a classroom consisting of a

teacher and pupils of another race to promote acquain-

tance and understanding.”

According to the present rate of teacher turnover, it would

take nearly a decade to accomplish the total desegregation of

the faculties by the maximum utilization of provision num-

ber one. Neither of the remaining provisions requires any

reassignment of the existing faculties. These provisions only

serve to transfer the onus of reassigning the teachers from the

school authorities to the individual teachers.

IX

The Reluctance of The Individual Teachers to Transfer to a School

Staffed with Teachers of the Opposite Race Cannot Be Permitted

To Defeat the Right of the Plaintiffs that Teachers Be

Assigned on a Non-Racial Basis.

As of June 30, 1966 the school board had sought and

failed to secure white teachers for the nine position vacan-

cies then existing in the two Negro schools and had assigned

only one Negro to teach in the predominantly white Charles

City School. (A. 35)

This fact, considered in light of the provisions of the plan

which indicated that no teacher would be transferred unless

he is willing to transfer, raised the question of whether the

11

teacher’s preference not to be transferred would justify the

board’s not requiring such transfer.

The District Court stated:

“One of the principal criticisms made by the plain-

tiffs is that faculty desegregation cannot be met without

changing assignments of teachers presently employed.

This problem was considered in Wheeler v. Durham

City Bd. of Education, No. 10,460 (4th Cir., July 5,

1966). There Judge Bryan said:

‘In the absence of the teachers as parties to this

proceeding, we do not think that the order should

require any involuntary assignment or reassign-

ment of a teacher. Vacant teacher positions in the

future, as the plaintiffs suggest, should be opened

to all applicants, and each filled by the best quali-

fied applicant regardless of race. Moreover, the

order should encourage transfers at the next ses-

sion by present members of the faculty to schools in

which pupils are wholly or predominantly of a race

other than such teacher’s.’

The plan complies with the requirements stated by the

Court of Appeals.” (A. 27)

The District Court apparently misconceived this Court’s

dictum in the Wheeler case. In the first place, the statement

in Wheeler has to be read with a background of an adequate

supply of teachers of both races available for the desegrega-

tion process. As stated by the Court:

“The presence in Durham of wives of students and

faculty members of Duke University and North Caro-

lina College who are qualified and available as teachers

provides a ready source of supply to meet any demand

for teachers of both races.” Wheeler v. Durham, supra.

Moreover, in view of the teachings of Brown, II and

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, that opposition to the princi-

12

ples of the Brown decision could not defeat those principles,

the Circuit Court obviously meant that teachers who were

not parties should not be reassigned involuntarily during the

remainder of the school year for which said teachers were

under contract. The extension of this privilege beyond this

period would necessarily mean that a teacher has a right to

contract to teach in schools staffed exclusively with teachers

of his race.

The duty of assigning teachers and administrative staff to

the various schools in the system on a non-racial basis rests

squarely upon the shoulders of the school authorities. The

full power of this Court should insure that this duty is ful-

filled.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, plaintiffs pray that the judgment of the Dis-

trict Court be reversed and that the Court be required to

enter such orders as necessary to insure the total desegrega-

tion of the faculties of the various schools and that the sepa-

rate overlapping attendance areas be merged into a single

unitary school system.

Respectfully submitted,

S. W. Tucker

Henry L. MarsH, III

WiLLarDp H. DoucLas, Jr.

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Jack GREENBERG

James M. Nagrit, 111

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Appellants