Motion to Dismiss or Alternatively to Affirm

Public Court Documents

July 3, 1978

17 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Motion to Dismiss or Alternatively to Affirm, 1978. 0a15ffb3-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96b36b48-8678-46b1-86c1-54d269173d68/motion-to-dismiss-or-alternatively-to-affirm. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

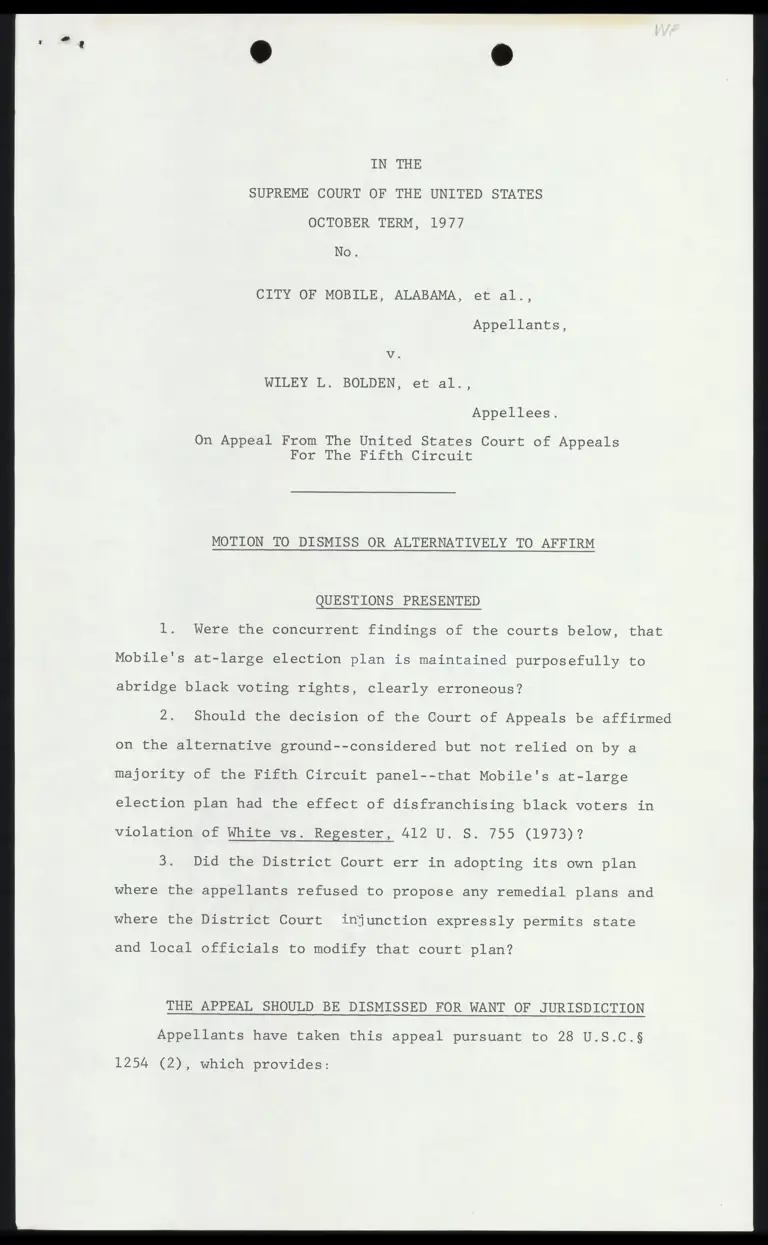

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1977

No.

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Appellants,

Vv.

WILEY 1.. BOLDEN, et al,,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States Court of Appeals

Por The Fifth Circult

MOTION TO DISMISS OR ALTERNATIVELY TO AFFIRM

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Were the concurrent findings of the courts below, that

Mobile's at-large election plan is maintained purposefully to

abridge black voting rights, clearly erroneous?

2. Should the decision of the Court of Appeals be affirmed

on the alternative ground--considered but not relied on by a

majority of the Fifth Circuit panel--that Mobile's at-large

election plan had the effect of disfranchising black voters in

violation of White vs. Regester, 412 U. S. 755 (1973)?

3... Did the District Court err in adopting its own plan

where the appellants refused to propose any remedial plans and

where the District Court injunction expressly permits state

and local officials to modify that court plan?

THE APPEAL SHOULD BE DISMISSED FOR WANT OF JURISDICTION

Appellants have taken this appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C.§

1254 (2), which provides:

Cases in the courts of appeals maybe

reviewed by the Supreme Court by the

following method:

(2) By appeal by a party relying on

a State Statute held by a court of appeals

to be invalid as repugnant to the Consti-

tution, treaties or laws OF the United

States, but such appeal shall preclude re-

view by writ of certiorari at the instance

of such appellant, and the review on ap-

peal shall be restricted to the Federal

questions presented....

In the instance case, the courts below have not held any

State statutes to be invalid. The statutes named on page

Jurisdictional Statement ..

5 -of the A” and set out in ppendices F and G thereto

are general laws of the State of Alabama, which remain in

full force and effect. It is one of the several optional

forms of municipal government authorized by Alabama law.

Mobile elected this particular form by referendum ballot in

1911. The decree affirmed below merely enjoins the City of

Mobile from continuing to use this optional form of municipal

government because of its at-large election feature. Every

other city in Alabama is free to adopt or continue using the

statutes in question. Therefore, jurisdiction of this appeal

is wanting under 28 U. 8. C.§ 1254(2).

This jurisdictional deficiency actually goes to the heart

of appellants' arguments supporting review by this Court and

reveals why they are insubstantial. It simply is not so that

the rulings below have ''created a constitutional guarantee

of certain political victory" for winority groups. J.S5.,

p.138. This case does not threaten any other city using the

commission form of government, id, nor does it impose "an

affirmative duty of racially-conscious electoral restructur-

ing upon legislatures." J. S., p.26. The courts below deter-

mined that Mobile was using the at large system authorized

by general law as a vehicle for intentional debasement of

blacks' voting rights. This finding is based on an exhaus-

1."Any city or town may adopt and become organized under

the commission form of government provided in this article by

proceeding as hereinafter provided." Ala. Code §11-44-71(1975).

J.8., p.iE.

tive analysis of the legislative, political and governmental

record unique to Mobile, Alabama. As the District Court points

out, quoting White vs. Regester, supra 412 U. S. at 769-70,

its opinion represents "a blend of history and an intensely

local appraisal of the design and impact of the ... multi-

n light ,¢ past and present member district [under scrutiny] i

reality, political and otherwise." J.8., p.41lb. This Court

could not reach the sweeping legal issues appellants had

sought to construct from the decisionsbelow without first re-

viewing all the svidenty and rejecting as clearly erroneous

a long list of purely factual findings.

support

The case is cited by appellants in of this Court's

jurisdiction provide them no help. In Dusch vs. Davis, 337

U. S. 112 (1967), this Court accepted a $1254 (2) appeal from

the decision of a Court of Appeals invalidating a municipal

charter for the City of Virginia Beach, Va., that had been

specifically approved by the legislature. Clark vs. Peters, 422

U. 8. 1031(1975), and Dallas County vs. Reese, 421 U. 8S. 477

(1975), were §1254 (2) appeals to this Court from federal ap-

pellatg/udgments invalidating local acts of the Alabama Legis-

lature adopting malapportioned district boundaries for local

government in specific counties. By contrast, the general law

relied on by the City of Mobile in the instant case has not

been declared invalid, and the Alabama Legislature has not by

some special or local enactment singled out Mobile's election

of a form of government for specific approval.

STATEMENT

Black citizens of Mobile, Alabama, brought this action in

June 1975 challenging the at - large system of electing mem-

bers of the Mobile City Commission. Following a 6-day trial,

in which 37 witnesses testified and 153 documentary exhibits

were introduced, and following a half-day tour of the City by

the District Judge, the trial court determined that the at-

large elections were being used purposefully and invidiously

to discriminate against black voters. The salient findings of

fact, affirmed in all respects by the Court of Appeals, are as

follows:

The Long History Of Voting Discrimination

Against Blacks In Mobile

The "Redemption'" of Alabama by the Bourbon Democrats from

Federal Reconstruction policies culminated with the enactment

of various so-called Progressive reforms. In Alabama, the Pro-

gressive movement included disfranchisement of blacks, because

they were considered a corrupting influence. The 1901 Alabama

Constitutional Convention was called for the primary purpose of

disfranchising blacks. The cumulative poll tax and grandfather

clause were the primary devices used to accomplish this. Dele-

gates from Mobile led the efforts to remove blacks from politics

in 1901, and some of these same white Mobilians promoted the

adoption of an at-large elected city commission for Mobile in

1911. Only token numbers of blacks were allowed to register and

vote until passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. J.S., pp. 19b-

20b 29b. Alabama operated an all-white Democratic primary until

well after it was outlawed by this Court in Smith vs. Allright,

321 U. S. 649 (1944). A white State legislator from Mobile was

chiefly responsible for the enactment of interpretation tests

as a device to prevent blacks from voting after the white primary

was struck down. The interpretation tests were declared unconsti-

tutional by the Federal Court in Mobile. Davis vs. Schnell

8L FF. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala. 1948), aff'd; 336 U. 8. 933 (1949).

In 1964, The Mobile County Legislative Delegation enacted

a special law to enable Mobile to change to a Mayor-Council,

form of government after a referendum election. A former State

Senator from Mobile| participated in the law's passage testified

that the local delegation chose to provide for at-large election

of the proposed council, rather than a single-member districts,

because of racial considerations:

Q. Why was the opposition to single-mem-

ber districts so strong?

A. At that time, the reason argued in

the legislative delegation, very simply, was

this, that if you do that, then the public

is going to come out and say that the Mobile

Legislative Delegation has just passed a bill

that would put blacks in City office. Which

it would have done had the City voters adopted

the Mayor-Council form of government.

The District Court found, as a matter of fact, that "[tlhese

factors prevented any effective redistricting which would

result in any benefit to the black voters passing until the

State was redistricted by a Federal Court order." J. S., p30b.

The Present Denial Of Effective Participation

In The Political Process

In the opinion of the court below, the total absence of

black elected officials in Mobile was only "[o]nlyzThdication

that local political processes are not equally open [to blacks]."

J. S., p. 7b. The District Judge also relied upon evidence pre-

senting a thorough analysis of racial politics in Mobile.

Expert statisticians and political scientists analyzedfmost

of the local elections in the city and county over the past 15

years. The unsuccessful candidacies of 4 black citizens who

1. The City of Mobile contains approximately two-thirds of

the population of Mobile County. The District Court considered

the election experiences of black candidates in county-wide races

to be relevant as well to an analysis of city politics. J. S. pp.6b-

10h,..13b n.

. “ »

sought school board seats, 3 blacks who ran for city commission

and 2 black candidates for at-large legislative seats were

thoroughly explored, as were the racial campaign tactics used to

stir up white backlash and defeat several candidates who dared

to espouse some interests of the black community. While most

white candidates actively seek black votes as well as white

votes, there was uniform agreement among the experts and poli-

ticians that, to be successful, a candi-

date must be careful not to be tagged with the "bloc [black]

vote," which is tantamount to the "kiss of death," according to

the City's own expert political scientist . All of the witnesses

(except one defendant city commissioner) agreed that it would be

difficult if not impossible for a black candidate to overcome the

solid racially polarized voting patterns in Mobile and win an at-

large election. Most of the prominent leaders and politicians in

the black community testified at trial, and without exception they

agreed that the futility of the effort prevented them from even

considering running for city commission under the at-large system.

The District Court accepted the opinion of plaintiffs’ expert

political scientist that black voting strength is "basically

cancelled or negated in the at-large structure in the Mobile City

elections."

Unresponsiveness Of Elected Officials

To Black Community Interests

Much of the long trial was devoted to evidence of how un-

fairly Mobile's all-white government has treated black citizens.

The District Court found that "[t]he at-large elected city

commissioners have not been responsive to the minorities' needs."

J.S8., p. 11b. To support this finding, the court's opinion re~-

fers first to continuing racial discrimination by the city in

employment. The Court still monitors compliance with its earlier

decree ordering desegregation of the Mobile Police Department.

Id. other Federal Court orders were required to desegregate public

facilities in the City of Mobile. J.S., p.12b. Blacks have been

Tap

appointed to important governmental boards and committees

only token numbers. J.S., pp.l12b-14b. Black residential areas

have suffered inequitable neglect with respect to such vital

services as drainage control, paving and resurfacing streets

and the placement of sidewalks. J.S., pp.l15b-17b.

Perhaps most importantly, the court found that city com-

missioners have been insensitive to long-standing complaints

of police brutality directed against blacks and the continuing

reoccurrence of cross burnings. In particular, the trial judge

was critical of the "timid and slow reaction' of city govern-

ment to investigate and discipline 7 white Mobile police offi-

cers who actually carried out a'mock lynching" of a black

suspect on a downtown street corner. It was confirmed, finally

that these officers placed a rope around the suspect's neck,

threw it over a live oak branch, and pulled the black man to his

tiptoes. The court found that the "sluggish and timid response"

of elected city officials to the lynching incident "is another

manifestation of the low priority given to the needs of black

citizens and of the political fear of a white backlash vote

when black citizens' needs are at stake." J. S. p.1l9%.

ARGUMENT

1. Notwithstanding appellants' extensive discussion

of the meaning and application of the dilution rule of

White v. Regester, 412 U. 8. 755 (1973), the decisions below

rest, in the first instance, not merely on the discriminatory

impact of the at-large election system, but on a finding of

fact that Mobile's system of electing Commissioners is motiva-

ted by an unconstitutional desire to discriminate against blacks.

J..8.,pp. 12a, :30b.. This case thus. presents, not just another

application of White v. Regester, but, primarily, an applica-

tion of Gomillion Vv, Lightfoor, 364 U. 8. 339 (1960), and Village

of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development

Corp., 429 0. 8.252 (1977).

The district court made a finding of discriminatory

intent after an exhaustive analysis of the evidence presented

at a six-day trial. J. S., pp. 286b ~ 31b. : The court of appeals

carefully scrutinized the record and concluded that the district

judge's detailed findings of fact were not clearly erroneous

and that they compelled a finding of discriminatory intent. J. S.

Pp. 12a. This Court does not ordinarily ''undertake to review

concurrent findings of fact by two courts below in the absence

of a very obvious and exceptional showing of error." Graver

Mfz. Co. Vv. Linde Co., 336 'U. 8S. 271, 275 (1961). No such

unusual circumstances are present here.

The record contains ample evidence to support the finding

that discriminatory intent lay behind the decision of the legis-

lature to maintain the at-large election of Commissioners in

Mobile. Until 1965 blacks were largely unable to register in

Mobile or elsewhere in Alabama, and racial discrimination in

voting had been the announced state policy since at least 1901.

The district court found, based on the direct testimony of

several state legislators who participated in consideration of

redistricting bills for Mobile, that the legislature would not

-

® »

pass "any effective redistricting which would result in any bene-

fit to black voters." J. S., p.30b. At-large elections were found

to effectively disenfranchise blacks in Mobile because of a parti-

cularly virulent hostility by white voters, who have not only

voted as a bloc against any black candidate for any office in

Mobile, but have also repeatedly defeated white candidates

who have been notably responsive to black needs. J. S., p./b-

10b. The decision below did not, as appellants claim, revolve

around some unstated premise that local governmental bodies

should reflect proportional minority representation, but rested

on the inability of black voters to have their electoral

choices -- whether whites or blacks -- registered through the

political process. J. S. pp. 9b - 10b. After detailed analysis

of all the election vetutng, the district court considered and

rejected appellants’ contention at trial that, just because

blacks sometimes vote for winners in elections that are not

racially polarized, they wield an effective ''swing vote."

Against this background of historical discrimination

against black voters in Alabama, and in light of a present leg-

islative practice of refusing to adopt redistricting measures

that might result in the election of blacks, the courts below

were entirely justified in concluding that the maintenance of

at-large voting in this particular case was racially motivated.

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp., supra, 429 U. S.

at 266-68. The lower courts did not ignore appellants' asser-

tion that the at-large elections have been used for over half

a century because they discourage the alleged corruption of

"ward-heeling"; they merely made a factual determination that that

somewhat implausible explanation was not the reason for main-

taining the present method of election.

, The decisions below express no preference for single-mem-

a political science standpoint. Beyond ]

Jodlidls ber districts as opposed at-large elections fromythe issue

a — Ee —— tia

a

of racial discrimination, political commentators disagree

whether the purported greater "efficiency" of at-large elected

local governments can offset their high price of political con-

-/0-

trol by strong financial interests and the loss of grass-roots

See Kendrick v. Walder, 527 P. 24 44.,51-54 (7th Cir.

input.

1975). (3. Pell Yispenring)

Ge ——— ea pape ETE————————— —— a car

Appellants suggest the courts below adopted a rule of law

that discriminatory intent must be inferred whenever a legis-

lature fails to adopt a districting plan it knows is favorable

to blacks. J. S., pp- 7, 24-26. Appellants point to no lan-

guage in either opinion adopting such a rule, and none is to

be found. On the contrary, the same panel of the Fifth Circuit

i

i

:

tf

”

.

i

.

i

i

Vd

a

a

fe

Ps

[

—

-

A

¢

Vv,

oe

‘

-

¢

-

—

~

[

3

-

i

:

pos

\

~

~

\

pe

~y

ry

"a

&

ay

+

§

”

3

|

p

-

J

pe)

J

ot

jd

A

3

’

i

|

:

g

l

y

PN

:

A

»

»

y

d

2

ad

rt

4

.

~

’

fod

f

vi

‘

-

.

:

»

Te

.

Ld

will

4

-

od

-

.

4.

.

43

r

n

5)

.

t

~

.

+’

J

A

ast

dt

Le

=

I

4

f

§

-

..

o

-

™

3

}

«

v

3

:

SE)

i

4

/

{

‘

ore

t

”

Oo

Sa

Ct

3

2

2

¢

-

x

’

a

7

i

-

pond

r

3

:

L

tr

§

8

4

™

.

Ca

{

§

v

J

®

peed

tld

r

c

d

fi

~

MN

i

.

1

,

:

4

Gd

~

£5

J

.

;

1

s

%

>

7

mf

w~

§

A

ig

i»

oo

*

¢

H

ih

1

po

’

Li

§

C

1

:

bo?

®

{

JJ

15

)

;

F

y

-

r

t

P

e

e

A

o

{

}

:

.

.

’

®

33

or

£

;

he

’

.

!

{

.

i

.

;

o

a

4

df

>

"

U

-

od

od a

1

£

wena)

.

r

a

p

}

cr

y

hd

¢

Jd

I

t

“

—

A

x

{

~

Le

py

>

4

f

s

“

-

:

:

N

-

4

ge

{

H

¥

eo

J

q

d

po

i

pot

_

fot

-

+

pe

-

v

-

£4

I

he

J

LW

hs

.

b

}

7

~

4

)

{

»

isd

*

=.

|

»

N

y

g

l

p-

peord

¥

:

i

t

n

d

é

“

\z

a!

q

[

a

y

i

Bou

J

\/

:

wp

owed

wd

\

a

y

-

/

.

o

{

fod

pod

bs

pr.

SS

i ;

J

*

{

a

’

Eh

¥

4

=

"

§

«pom

.

;

;

je

~™

so

%

i

»

[81

>.

bes

het

He

d

-

n

pod

-

ac

J

bi

’

.

c

5

4

,

oo

+

;

.

Gg

oped

i

=

N

;

.

)

rod

7

»

\

de

)

9

.

—

r

4

—

A

|

pi

:

:

:

5

P

=

1

t

d

{

|

~4

#

—

1)

t

»

«ge

"

MN

~

r

er"

C

{

f

/

"

“

-

“

,

.

py

;

*

i

,

—

|»

~<

+

.

:

-

-_]d~

i 7 X {. £33

4 % 3 . % In § by § ¢

” ce

n 3

4 - ™

$ 1 ER » . ® J

. v - 4 a iL A

" » “4 ¢

4 § 8 - h: wo

a Pz

of 3 ) 3 Y at "TT

5 whe he A Ae bo 4

ho iid

il { 1.8 : ” A

oh on yy en “

p

PERE my, foe

(& \ | 99

fe . - ; "

ne i x wo LS

doe n “ Pho 5 - on

Lad ild Ck i LI 3 ty

ny

!

>

~

)

on IS ad a

LF Sg

=

3

4

: lan re

ds

Ye WJ ux te

Pia Pre > a a

Ners ®) 1

4) ne

4

43

®

3

«

0

by

4

3

1

8

§

+

i

[14]

i

h

~

|

a)

v

i

Q

i

=

i

f

=

. — 15 »

3. The Jurisdictional Statement contains a question re-

garding the remedy fashioned by the district court, and the

history of that issue is delineated, but the matter is not

discussed at length in the body of the Jurisdictional State-

ment. J. S., Dp.4, 15-16.

The appropriateness of the remedy was properly analyzed

by the court of appeals. J. S., pp. 1l5a-17a. Appellants

inexplicably refused in the district court to offer any plan

for the conduct of elections or the creation of single-member

districts. Under that circumstance it was the obligation "of

the federal court to devise and imposé a reapportionment plan."

Wise v. Lipscomb, 46 U.S.1..W. 4777, 4779 (1978). Manifestly

some alteration in Mobile's method of election was required

to remedy the proven violation, and since the plan was ordered

by the district court it was required to prefer single-member

districts. Id. Appellants' recalcitrant refusal to assist: in

the framing of a decree forced the district court to re-

solve the details of a plan which it would have preferred to

leave to state or local authorities; for this reason the court's

decree expressly provides that state and local officials retain

their authority to alter the plan adopted by the court in any

respect other than the reinstitution of at-large seats, J.S.,

pp. 2d-3d {Appellants imply that the trial court abused its

discretion by formulating a ''sErong mayor" plan (based on a

synthesis of special statutes governing Birmingham and Mont-

gomery) instead of utilizing the "weak mayor" option offered

by general law. J.S., p.13n.17. In fact, it was at the instance

of appellants' counsel, who during and after trial pleaded with

the court not to employ the "weak mayor" form as a remedy,

that the district judge appointed a blue-ribbon panel to de-

velop an interim ''strong mayor" plan. Other misleading state-

ments in the Jurisdictional Statement include inferences that

the court-ordered plan calls for partisan elections, J.S., p.22

n. 26, and that Moblle presently has a city charter, J. S.,

PP. 2, 15. Actually, (he district court's injunction retains

the nonpartisan election feature of Mobile's present system.

Na es *

J. 5. %pp. 74 - 9d. And Mobile has never . been governed under

a charter, to the extent that term is popularly understood

as meaning local home rule. For Mobile to be reapportioned

or to change its form of government requires either action by

the state legislature or a referendum election to change to

one of the other optional municipal forms of government pro-

vided by general law. Appellants did not attack this remedy

in the court of appeals, except to argue that no remedy was

possible because at-large elections are an integral part of

commission government. In any event, the appellants, having

failed in 1976 to offer the district court any proposed remedial

plan, cannot now complain in this Court about the details of

the plan actually adopted.

-)7-