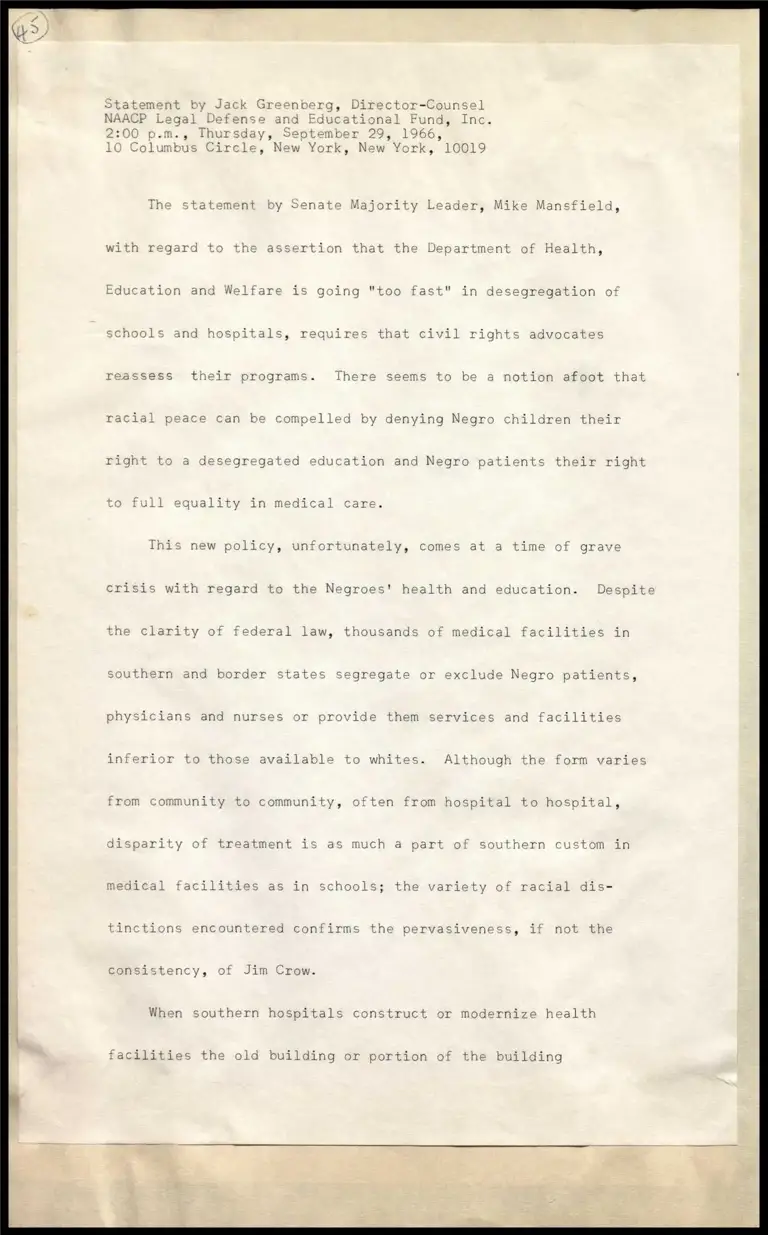

J. Greenberg Statement on School and Hospital Desegregation

Press Release

September 29, 1966

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 4. J. Greenberg Statement on School and Hospital Desegregation, 1966. 89a1003f-b792-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96b7577c-ff80-4635-9006-d6f260b130e3/j-greenberg-statement-on-school-and-hospital-desegregation. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

t

cP

ector-Counsel

ducational Fund, Inc

r 29, 1966,

ew York, 10019

a

NAA

NAA\

Majority Leader, Mike Mansfield,

assertion that the Departm 2alth,

segregation of

by denying Negro ldren their

their right

new policy, unfortunately, comes at a time of grave

with regard to th ' health and ucation. Despite

medical faciliti

or services and facilities

.« Although the form varies

of

When southern hospitals construct or modernize health

facilities the old building or portion of the building

conventionally becomes a restricted area, Where a building

or floor is shared, a hospital may maintain separate wards,

private or semi-private rooms, lavatories, eating facilities,

entrance ways, emergency rooms, maternity wards or nurseries.

Some hospitals provide one ambulance service for whites,

another for Negroes; others schedule out-patient clinics on

"Negro" and "white" days or segregate thermometers.

A Florida hospital developed the practice of placing Negroes

in the basement unless they were "prominent" and one

Mississippi facility has refused to permit Negroes to visit

"white" wards. At many hospitals, when a Negro seeks ad-

mission he is required to show greater financial security

than a white and is turned away if he does not demonstrate

ability to pay. Although refusal to admit Negro emergency

patients is said to be a thing of the past, an alarming

number of seriously ill Negroes are refused hospital admission

until a guarantor of their fees can be found. Segregation

also means a gross disparity in physical conditions and pro-

fessional services; a surprising number of southern hospitals

force Negro patients--male and female--to use a single lava-

tory; and a common method of obtaining rooms for whites is

($6

JACK GREENBERG

to move Negro beds into hallways when the white section of

the hospital has been filled. Negro patients complain of

antiquated facilities, poor service and outright discourtesy

from hospital personnel.

Discrimination against Negro professionals is also preva-

lent. Negro physicians and dentists encounter difficulty in

gaining free access to hospital staffs, forcing them to turn

patients over to white physicians for hospitalization, much

to their financial detriment, or to offer treatment in private

clinics which cannot offer the facilities or services of

government or community hospitals. The numerous professional

and educational benefits of affiliation with the American

Medical Association and American Dental Association are often

privileges restricted to white practitioners. If a hospital

employs Negro nurses (and many do not), they are rarely promoted

to supervisory positions and are often paid less than white

nurses for the same work, Despite a pressing national need,

hospital-affiliated nursing schools still exclude Negroes or

minimize their numbers and few southern hospitals train Negroes

for expanding job opportunities in technical fields, such as

Operation of X-ray machines and occupational and vocational

therapy.

JACK GREENBERG

There is a strong correlation between the consequences of

racial discrimination in health facilities and services

and the depressed status of Negro health.

The Negro American, in comparison with his white

fellow citizen, has more diseases and disabilities; one-third

more days when he is unable to function at full physical

capacity; is sick enough to require bed rest on twice as many

days; loses one and one-third times more days from work due

to disease and disability; has a higher mortality rate, in-

cluding a 90 per cent differential in infant mortality and

seven years shorter life expectancy.

To summarize: mm of every 1,000 white Americans in

their late forties, five will die in the coming year. If

they are Negro, ten will die.

The Legal Defense Fund has filed hundreds of complaints

of hospital discrimination with the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare. We are now litigating 15 cases against

Seas

in numerous southern sta

lic aware-

the news m has held back federal funds only

al are locate

Yet majority’ lead 4 Mansfield concludes that o fea

i i) Q Q 8

has come to the

donsibility

right in our lap. the prece we assumed

the government would compel to the law. We are moving

to rearrange our present cas

We had un Gu

a a 3) =

the

numerous requests from representative

organiz to file litigation with regards to

schools. made a policy to hold down the number

of cases we were carrying in this area because we were laboring

a

nberg

under the impression that the federal government was

what it promised and we wanted to expand programs in

will noW acc for additional lawsuits in the

health and education. This will cause a realignment in ths

of our New York based attorneys and our more than

the south.

We will, » continue to

our program and will, of necessity, prog to

finan ility.