Lytle v. Household Manufacturing Inc. Reply Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

November 30, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lytle v. Household Manufacturing Inc. Reply Brief for Petitioner, 1989. e1141929-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96c1e600-ef94-4862-8203-d8545259a68a/lytle-v-household-manufacturing-inc-reply-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

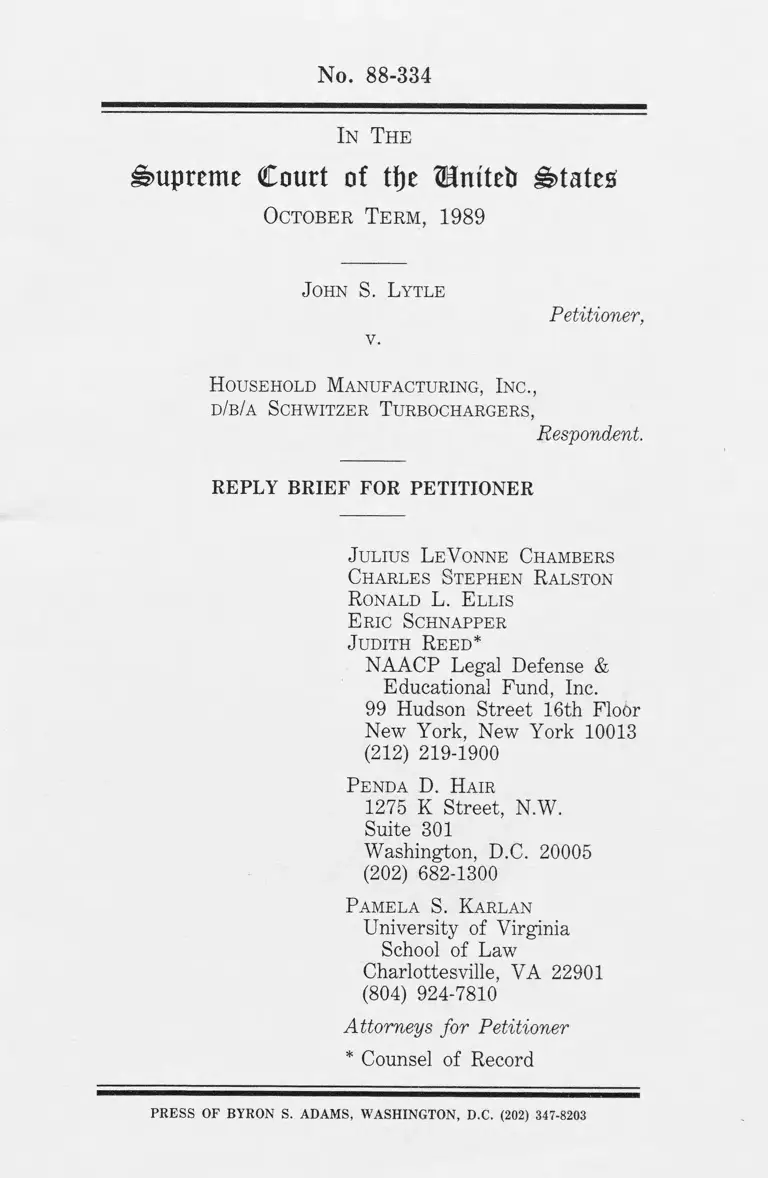

No. 88-334

In The

Supreme Court of tf)e 3Umteti s ta tes

October Term, 1989

J ohn S. Lytle

v.

Petitioner,

Household Manufacturing, Inc.,

d/b/a Schwitzer Turbochargers,

Respondent.

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Ronald L. E llis

E ric Schnapper

J udith Reed*

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

P enda D. Hair

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Pamela S. Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

Attorneys for Petitioner

* Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

CONTENTS

I. The Seventh Amendment Compels Reversal of

the Court of Appeals’ Judgment . . . . . . . . . 1

II. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Does Not

Preclude Petitioner From Maintaining This

Action ................................................................ 10

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc.,

477 U.S. 242 (1986)...................... ........................ .. . 5, 6

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley

Authority, 297 U.S. 288 (1936) . .................................... 16

Bhandari v. First National Bank of

Commerce, 106 L. Ed. 2d 558 (1989) _____ _______ 15

Birdwhistle v. Kansas Power and

Light Co., 51 FEP Cases (D. Kan. 1989) . ............. .. 18

Booth v. Terminix International,

1989 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 10618

(D. Kan. 1989) .......................................................... 18

Brady v. Allstate Insurance Co.,

683 F.2d 86 (4th Cir.), cert, denied,

459 U.S. 1038 (1 9 8 2 ).......... ......................................... 11

Cardinale v. Louisiana,

394 U.S. 437 (1969) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ____. . . . . 14

Carella v. California,

105 L.Ed.2d 218 (1989) ................ 1

Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18 (1 9 6 7 ).........................2

ii

Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson,

404 U.S. 97 (1971)......................................................... 30

Choudhury v. Polytechnic

Institute of New York,

735 F.2d 38 (2d Cir. 1984) .......................................... 13

Coates v. Johnson & Johnson,

756 F.2d 524 (7th Cir. 1985)....................................... 11

Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41 (1957) ......................... 23, 28

Conner v. Fort Gordon Bus Co.,

761 F.2d 1495 (11th Cir. 1985) .................................... 11

Continental Casualty Co. v. DHL Services,

752 F.2d 353 (8th Cir. 1985).......................................... 4

Delaware State College v. Ricks,

449 U.S. 250 (1980) ..................................... ................ 21

DeMatteis v. Eastman Kodak Co.,

511 F.2d 306 (2d Cir. 1975),

modified on other grounds,

520 F.2d 409 (2d Cir. 1975) ........................................ 13

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968)........................... 2

Cases Page

English v. General Development Corp.,

50 FEP Cases 825 (N.D.I11. 1989) . 14, 25

Cases Page

Fong v. American Airlines, Inc.,

626 F.2d 759 (9th Cir. 1980) ......................... .............. 11

Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC,

458 U.S. 219 (1982) ..................................... ................ 19

Gairola v. Commonwealth of Virginia

Dept, of General Services,

753 F,2d 1281 (4th Cir. 1 9 8 5 )........................................5

Galloway v. United States,

319 U.S. 372 (1943) . ...................................................... 2

Goff v. Continental Oil Co.,

678 F.2d 593 (5th Cir. 1982)........................................ 13

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.,

482 U.S. 656 (1987) ........................................... 21, 29, 32

Granfinanciera S.A. v. Nordberg,

109 S.Ct. 2782 (1989) ....................................................... 1

Greenwood v. Ross, 778 F.2d 448

(8th Cir. 1985) . . . . . . . ....................................... 13

Gunning v. Cooley, 281 U.S. 90 (1930)................................ 6

Hannah v. The Philadelphia

Coca-Cola Bottling Co.,

1989 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 7200 (E.D.Pa. 1989) ............... 14

IV

Cases Page

Harris v. Richards Mfg. Co.,

675 F.2d 811 (6th Cir. 1982)........................................ 13

Jackson v. University of Pittsburgh,

826 F.2d 230 (3d Cir. 1988) ........................................ 11

Johnson v. Yellow Freight System, Inc.,

734 F.2d 1304 (8th Cir.),

cert, denied, 469 U.S. 1041 (1984).............................. 11

Jones v. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers,

1989 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 10307

(W.D.Mo. 1989)................................ ................... 19, 20

Leroy v. Great Western United Corp.,

443 U.S. 173 (1979) ....................................................... 16

London v. Coopers & Lybrand,

644 F.2d 811 (9th Cir. 1981) . ......................................13

Long v. Laramie County

Community College Disk,

840 F.2d 743 (10th Cir. 1 9 8 8 )................................ .. . 13

Lopez v. S.B. Thomas, Inc.,

831 F.2d 1184 (2d Cir. 1987) ..................................... 11

Malhotra v. Cotter & Co.,

50 FEP Cases 1474 (7th Cir. 1989)...................... 15, 25

v

Cases Page

Martin v. New York Life Ins. Co.,

148 N.Y. 117, 42 N.E. 416 (1895) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail

Transportation Co., 427 U.S. 273 (1976) . . . . . . . . . 21

McDonnell Douglas v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1978) . ..................................................... 20

Meeker Oil v. Ambassador Oil Corp.,

375 U.S. 160 (1963) .................................................. . . . 1

Padilla v. United Air Lines,

716 F. Supp. 485 (D. Colo. 1989)................................ 20

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

105 L. Ed. 2d 132 (1989) ................................... passim

Pinkard v. Pullman-Standard,

678 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1982),

cert, denied,

459 U.S. 1105 (1 9 8 3 ).................................................... 13

Pope v. City of Hickory, N.C.,

679 F.2d 20 (4th Cir. 1982)............................................. 33

Prather v. Dayton Power &

Light Co., 1989 U.S. Dist.

LEXIS 10756 (S.D.Ohio 1989)..................................... 14

vi

Cases Page

Pullman Standard v. Swint,

58 U.S.L.W. 3288 (1989)............................................... 15

Ramsey v. United Mine Workers,

401 U.S. 302 (1971)....................................................... 12

Rowlett v. Anheuser-Busch, Inc.,

832 F.2d 194 (1st Cir. 1 9 8 7 )........................................ 11

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc.,

431 F.2d 1097 (5th Cir. 1970),

cert, denied, 401 U.S. 948 (1971)................................ 11

Setser v. Novack Investment Co.,

638 F.2d 1137 (8th Cir.),

modified, 657 F.2d 932, cert, denied,

102 S.Ct. 615 (1981) ....................................................... 13

Sisco v. J.S. Alberici Const. Co.,

655 F.2d 146 (8th Cir. 1981),

cert, denied, 455 U.S. 976 (1982).......... ..................... 13

St. Francis College v. Al-Khazraji,

481 U.S. 604 (1987) . ................................... 21, 31, 33

Stearns v. Beckman Instruments, Inc.,

737 F.2d 1565 (Fed.Cir. 1984).........................................4

Strickland v. Washington,

466 U.S. 668 (1984)........................................................... 2

vii

Swint v. Pullman Standard,

58 U.S.L.W. 3288 (1989)............... ..................... .. 15

Tacon v. Arizona, 410 U.S. 351 (1973) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Thomas v. Beech Aircraft Corp.,

1989 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 11284 (D. Kan. 1989) . . . . . 32

Tull v. United States,

481 U.S. 412 (1987)............................................................1

United States v. Lane,

474 U.S. 438 (1 986 ).............. 2

Whiting v. Jackson State University,

616 F.2d 116 (5th Cir. 1980)............................. 13

Wilson v. Garcia, 471 U.S. 261 (1985) ................................31

Wilson v. United States,

645 F.2d 728 (9th Cir. 1981) .................... ................... 5

Winston v. Lear-Siegler Inc.,

558 F.2d 1266 (6th Cir. 1977) . . . . . . . . . . . . ____13

Cases Page

viii

Constitutional Provisions.

Statutes, and Rules Page

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ........................................................... passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b)............................................................26

Rule 41(b), Fed. R. Civ. P..............................................3-7, 10

Rule 50, Fed. R. Civ. P....................................................... 3, 5

Rule 52(a), Fed. R. Civ. P........................................................4

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, as amended, 1972 ................. 12, 26-28, 33, 34

U.S. Const. Amend. V I I ................. ......................1, 2, 10, 16

Other Authorities

Corbin on Contracts (1952).................................................. 18

5 Moore’s Federal Practice (2d ed. 1 9 8 8 )........................... 5

9 Wright & Miller,

Federal Practice and Procedure (1971) .........................5

ix

I. The Seventh Amendment Compels Reversal

of the Court of Appeals’ Judgment

Respondent raises two analytically independent

reasons why the denial of a jury trial in this case does not

compel reversal of the dismissal of petitioner’s claims.

First, respondent claims that no denial of petitioner’s

Seventh Amendment rights ever occurred. Second,

respondent argues that this Court should sanction the

total disregard of the Seventh Amendment by lower

courts.1 Neither argument is supported by either this

1 This latter argument has two parts. The first concerns the

application of collateral estoppel to deny a jury trial. As we

explained in our opening brief, the Fourth Circuit’s approach - to

ignore Seventh Amendment violations as insignificant procedural

mishaps, and ask only whether the trial judge’s findings were clearly

erroneous -- would effectively write the Seventh Amendment out of

the Constitution. Brief for Petitioner (Pet. Br. 47-50).

The second, that the denial of a jury in this case was

harmless error, also fails. This Court’s traditional practice when

confronted with Seventh Amendment violations is a rejection of that

approach. See Pet. Br. 35-38, discussing, e.g., Granfinanciera S.A. v.

Nordberg. 109 S.Ct. 2782 (1989); Tull v. United States. 481 U.S. 412

(1987); Meeker Oil v. Ambassador Oil Corp.. 375 U.S. 160 (1963).

Moreover, that approach ignores the fundamental nature of the right

to a jury trial. "The constitutional right to a jury trial embodies ’a

profound judgment about the way in which the law should be

(continued...)

Court’s prior decisions or by logic.

Respondent concedes, as it must, that the Court of

Appeals found that petitioner’s Seventh Amendment

rights had been denied. But it seeks to support the

Court of Appeals’ judgment by arguing that the result «

affirmance of the district court - was right even though 1

1 (...continued)

enforced and justice administered.’" Carella v. California. 105 L.Ed.

2d 218, 223 (1989) (Scalia, J. concurring in the judgment) (quoting

Duncan v. Louisiana. 391 U.S. 145, 155 (1968)). "It is a structural

guarantee that ’reflect[s] a fundamental decision about the exercise

of official power -- a reluctance to entrust plenary powers over the

life and liberty of the citizen to one judge or to a group of judges.’"

Id. (emphasis added). It is only after that constitutionally mandated

structure is in place that a court may even begin to conduct a

harmless-error analysis.

In any event, application of the appropriate harmless-error

standard (i.e., Chapman v. California. 386 U.S. 18, 24 (1967) and

United States v. Lane, 474 U.S. 438, 446 n. 8 (1986)), to the instant

case would require reversal, if this Court concludes that a properly

impaneled and instructed jury could have found for Lytle. Galloway

v. United States, 319 U.S. 372, 396 (1943). Given the evidence in

this case, it is clear beyond any doubt that a jury that believed

petitioner’s testimony could have found for him on both his

discharge and retaliation claims. Since there is a reasonable

possibility that the outcome would have been different had the error

not occurred — the standard used in constitutional harmless error

cases - reversal is required. See, e.g., Strickland v. Washington. 466

U.S. 668, 694 (1984).

2

the entire analysis used to support that result was wrong.

Respondent’s argument, however, substantially distorts the

case law and Federal Rules of Civil Procedure on which

it relies.

Put simply, respondent claims that since the

evidence in this case would have compelled a directed

verdict, the district court should have taken the case from

the jury at some point, there was no error in never

empaneling a jury to begin with. That argument

bespeaks both a critical misunderstanding of the

relationship between Rule 41 dismissals in bench trials

and Rule 50 directed verdicts in jury trials and a critical

mischaracterization of the evidence at issue in this case.

The district court dismissed petitioner’s

discriminatory discharge claim at the close of his case,

pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(b). Contrary to

respondent’s suggestion, that dismissal was not equivalent

3

to the ruling the district court would have been called

upon to make had it been faced with a motion for a

directed verdict in a jury case. Rule 41(b) applies by its

own terms only "in an action tried before the court

without a jury." It directs the judge to determine whether

"upon the facts and the law the plaintiff has shown no

right to relief' (emphasis added). It explicitly provides

that "the court as trier of the facts may determine them."

Id. If the court enters a Rule 41(b) dismissal against the

plaintiff, it "shall make findings as provided in Rule

52(a)." Id-2

2 As recently explained by the Court of Appeals for the

Eighth Circuit: "In ruling on a motion for directed verdict, the judge

must determine if the evidence is such that reasonable minds could

differ on the resolution of the questions presented in the trial,

viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the plaintiff.

On a motion for directed verdict, the court may not decide the facts

itself. In deciding a Rule 41(b) motion, however, the trial court in

rendering judgment against the plaintiff is free to assess the

credibility of witnesses and the evidence and to determine that the

plaintiff has not made out a case." Continental Casualty Co. v. DHL

Services, 752 F.2d 353, 355-56 (8th Cir. 1985). Accord Stearns v.

Beckman Instruments. Inc.. 737 F.2d 1565, 1567 (Fed.Cir. 1984)

(judgment under Rule 41(b) "need not be entered in accordance with

(continued...)

4

In a case tried before a jury, of course, these

functions are the exclusive province of the jury, not the

judge. Thus, there are a number of fundamental

distinctions between dismissals pursuant to Rule 41(b)

and granting of directed verdicts pursuant to Rule 50(a).

First, in deciding a motion for a directed verdict,

the court may neither make credibility judgments adverse

to the nonmoving party nor weigh the evidence.2 3 Second,

in deciding whether to grant a directed verdict, the court

must view all the evidence and make all the factual

inferences in the light most favorable to the nonmoving

2(...continued)

a directed verdict standard"); Wilson v. United States. 645 F.2d 728,

730 (9th Cir. 1981) ("The Rule 41(b) dismissal must be distinguished

from a directed verdict under Rule 50(a)"). See generally 5 Moore’s

Federal Practice 1 41.13[4] at 41-175 to 41-179 (2d ed. 1988).

3 Anderson v. Liberty Lobby. Inc.. 477 U.S. 242, 255 (1986)

("[credibility determinations, the weighing of the evidence, and the

drawing of legitimate inferences from the facts are jury functions, not

those of a judge"). Gairola v. Commonwealth of Virginia Dept, of

General Services. 753 F.2d 1281, 1285 (4th Cir. 1985); 9 Wright &

Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure: Civil § 2524 at 541-42; §

2536 at 593-95 (1971).

5

party.4 Finally, a court may not weigh conflicting

evidence.5

By contrast, in deciding a Rule 41(b) motion, the

judge is not required to afford these burden-shifting and

burden-heightening rules. Thus, when a judge decides a

Rule 41(b) motion, he decides which side he believes, and

not whether all reasonable people would be compelled to

favor that side. In short, the standard in a Rule 41(b)

case more nearly resembles the standard used in de novo

review (i.e., "which side should win?") rather than the

standard used in directed verdict determinations (i.e.,

"could any jury find for the other side?").

4 Anderson v. Liberty Lobby. Inc.. 477 U.S. at 255; see also.

cased cited Pet. Br. 31 n. 18.

5 Where there is any "uncertainty” as to the issue before the

jury which "arises from a conflict in testimony or because, the facts

being undisputed, fair-minded men will honestly draw different

conclusions from them, the question is not one of law but of fact to

be settled by the jury." Gunning v. Cooley. 281 U.S. 90, 94 (1930).

6

The district court’s approach in this case provides

a paradigmatic illustration of this general principle.

Three examples will suffice. First, the district court’s

finding that plaintiff had 9.8 hours of excessive unexcused

absence was crucial to its dismissal of the discharge claim.

That finding necessarily rejected petitioner’s testimony

that his absences were due to his doctor’s appointment

and his physical inability to work, and that respondent’s

policy treated absences due to these kinds of reasons as

excused absences granted as a matter of course. It might

well be that a jury could disbelieve Lytle. But on a

directed verdict motion, the judge could not have made

that determination. Indeed, he would have been required

to assume that the jury would find for Lytle if any

reasonable jury could do so. And so the judge’s Rule

41(b) finding reflects an issue that would have had to go

to the jury in a jury case.

7

Second, the court declined to find that white

employees charged with lateness or absence were treated

more leniently that Lytle had been. Again, while a jury

might have been entitled to reject Lytle’s claim, that

rejection would have depended on an assessment of

Lytle’s credibility as well as that of any of respondent’s

supervisory personnel who might have testified that

Lytle’s situation was distinguishable. That rejection would

not have been within the judge’s province in a jury trial

case.

Finally, the district court expressly recognized that

it was making findings of fact about issues on which

reasonable individuals could differ. Lytle’s trial counsel

suggested that "the only reason Mr. Lytle is being charged

with unexcused absence . . . is because of Mr. Larry

Miller’s decision not to consider Friday a vacation day

and to make Saturday a mandatory 8-hour overtime work

8

period. And the misunderstanding that Mr. Lytle had

about that is the only reason he didn’t call in." Tr. 252-

53. In response to an objection that the argument was

"not necessarily supported by the evidence here" the

Court stated: "It’s a reasonable interpretation of the

evidence." Tr. 253. Ultimately, however, the district

judge rejected this "reasonable interpretation," presumably

in favor of one he found more "reasonable." But,

importantly, the court’s statement acknowledges that a

jury could have found for Lytle.6 In light of this

acknowledgement, it is simply wrong to contend that the

6 Similarly, with regard to Lytle’s claim of retaliation, a jury

might well have concluded that the letter of reference given a white

employee discharged during the same year was not inadvertent as the

district judge found, but that no such reference was given to Lytle

because he had taken action to redress an alleged violation of his

federally granted rights.

9

Rule 41(b) dismissal was equivalent to a directed verdict,

and thus that no Seventh Amendment violation occurred.7

II. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union

Does Not Preclude Petitioner From

Maintaining This Action

Respondent urges as an alternative ground for

affirmance that petitioner’s section 1981 claims are

precluded by this Court’s recent decision in Patterson v.

McLean Credit Union. 105 L. Ed. 2d 132 (1989). Brief

for Respondent (R. Br.) 1-18. We agree that, if this case

is remanded for a jury trial, respondent could seek to

invoke Patterson in any subsequent litigation regarding

the scope of section 1981. There is no denying that

7 Respondent’s reliance on the Miller and Lane affidavits

regarding petitioner’s discharge claim (presumably as a proxy for the

testimony they would have offered had they actually testified at trial

- which they did not) necessarily means that they are not claiming

that a directed verdict would have been appropriate at the end of

petitioner’s case in chief - since the evidence on which respondents

rely would not have been in the record at that time ~ but rather at

the end of respondent’s case.

10

Patterson raises a wide variety of complex and novel

issues about the interpretation of section 1981. But we

believe that this Court should not undertake to address

those issues in the context of the instant case.

Respondent asks this Court to hold that section

1981 does not apply to racially motivated discharges.8

But as respondent implicitly concedes (R. Br. 12),

respondent did not raise that issue in the district court or

the court of appeals.9 The respondent in Patterson itself

8 Respondent construes Patterson as overruling the dozens of

circuit decisions holding section 1981 applicable to discharge claims.

See, e.g., Rowlett v. Anheuser-Busch. Inc.. 832 F.2d 194 (1st Cir.

1987); Lopez v. S.B. Thomas. Inc.. 831 F.2d 1184 (2d Cir. 1987);

Jackson v. University of Pittsburgh. 826 F.2d 230 (3d Cir. 1988);

Brady v. Allstate Insurance Co.. 683 F.2d 86 (4th Cir.), cert, denied.

459 U.S. 1038 (1982); Sanders v. Dobbs Houses. Inc.. 431 F.2d 1097

(5th Cir.) cert, denied. 401 U.S. 948 (1971); Coates v, Johnson &

Johnson. 756 F.2d 524 (7th Cir. 1985); Johnson v. Yellow Freight

System, Inc.. 734 F.2d 1304 (8th Cir.), cert, denied. 469 U.S. 1041

(1984); Fong v. American Airlines. Inc.. 626 F.2d 759 (9th Cir.

1980); Conner v. Fort Gordon Bus Co.. 761 F.2d 1495 (11th Cir.

1985).

9 Respondent agreed in the Fourth Circuit that section 1981

generally "prohibits employment discrimination on the basis of race."

(Brief for Appellee, No. 86-1097, 4th Cir., p. 38). Respondent did

not argue that petitioner could not have maintained an action, based

(continued...)

11

had failed to raise below any argument that section 1981

precluded Patterson’s section 1981 promotion claim; for

that reason the Court declined to resolve the sufficiency

of that particular claim. 105 L. Ed. 2d at 156. Here, as

in Patterson, the Court should adhere to its general

practice of not addressing in the first instance issues not

raised or resolved below. Tacon v. Arizona. 410 U.S.

351, 352-53 (1973); Ramsey v. United Mine Workers. 401

U.S. 302, 312 (1971). Respondent argued in the court of

appeals that section 1981 does not prohibit the particular

form of retaliation alleged by petitioner, but that

argument was based on a theory quite unrelated to the 9

9(...continued)

solely on section 1981, for a racially motivated discharge. Rather,

respondent’s sole contention in the lower courts was that petitioner

forfeited his right to enforce the section 1981 prohibition against

discriminatory discharge when petitioner "combine[d]" that section

1981 claim with a Title VII claim in the same complaint. (Id. at 37).

Respondent denied that "Title VII and § 1981 claims may be brought

together on the same facts," (id. at 40), an argument that would have

been equally applicable to a section 1981 hiring claim. In this Court

respondent has abandoned this contention.

12

holding in Patterson.10 The court of appeals, moreover,

did not resolve any question regarding the applicability of

section 1981 to acts of retaliation.11 Here too it would

be prudent to permit the sufficiency of the retaliation

claim to be addressed in the first instance by the lower

courts on remand. "Questions not raised below are those

on which the record is very likely to be inadequate, since

10 Respondent urged below that the complaint failed to allege

with sufficient specificity that the retaliatory act was racially

motivated. (Brief for Appellee, No. 86-1097, 4th Cir., pp. 37-40).

11 Prior to Patterson, there was a consensus among the

circuits that section 1981 was indeed applicable to retaliation. See,

e.g., Choudhurv v. Polytechnic Institute of New York. 735 F.2d 38

(2d Cir. 1984); DeMatteis v. Eastman Kodak Co.. 511 F.2d 306, 312

(2d Cir. 1975), modified on other grounds. 520 F.2d 409 (2d Cir.

1975); Goff v. Continental Oil Co.. 678 F.2d 593. 598 (5th Cir.

1982); Pinkard v. Pullman-Standard. 678 F.2d 1211, 1229, n.15 (5th

Cir. 1982) (per curiam), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1105 (1983);

Whiting v. Jackson State University. 616 F.2d 116 (5th Cir. 1980);

Harris v. Richards Mfg. Co.. 675 F.2d 811, 812 (6th Cir. 1982);

Winston v. Lear-Siegler Inc., 558 F.2d 1266, 1268-70 (6th Cir. 1977);

Greenwood v. Ross. 778 F.2d 448, 455 (8th Cir. 1985); Sisco v. J.S.

Alberici Const. Co.. 655 F.2d 146, 150 (8th Cir. 1981), cert, denied.

455 U.S. 976 (1982); Setser v. Novack Investment Co.. 638 F.2d 1137,

1146 (8th Cir.), modified. 657 F.2d 932, ceru denied. 102 S.Ct. 615

(1981); London v. Coopers & Lvbrand. 644 F.2d 811 (9th Cir. 1981);

Long v. Laramie County Community College Dist.. 840 F.2d 743

(10th Cir. 1988).

13

it certainly was not compiled with those questions in

mind." Cardinale v. Louisiana. 394 U.S. 437, 439 (1969).

Respondent suggests that its prior failures to

object to the section 1981 claims should be excused

because the recent decision in Patterson was an

"intervening change in controlling law." R. Br. 12. But

the complaint whose sufficiency respondent now seeks to

challenge also predates Patterson. Neither the complaint

nor the answer in this case were or could have been

framed with Patterson "in mind."12 In the wake of

Patterson the lower courts have generally permitted

section 1981 plaintiffs to amend their complaints and

pursue necessary additional discovery,13 sensitive to Judge

12 The section 1981 claims themselves were never tried, having

been dismissed on a ground which the court of appeals held, and

which respondent does not deny, was erroneous. Pet. App. 7a n. 2.

13 English v. General Development Corp.. 50 FEP Cas. 825

(N.D.I11. 1989); Hannah v. The Philadelphia Coca-Cola Bottling Co.

1989 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 7200 (E.D.Pa. 1989); Prather v. Dayton Power

& Light Co.. 1989 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 10756 (S.D.Ohio 1989).

14

Posner’s admonition that judges should recognize that

such plaintiffs often face unusual difficulties when they

are compelled to "negotiate the treacherous and shifting

shoals of present-day federal employment discrimination

law." Malhotra v. Cotter & Co.. 50 FEP Cases 1474,

1480 (7th Cir. 1989). The resolution of any issues raised

by Patterson regarding the claims in this case should

await whatever clarification such amendment or discovery

might bring. Here, as in other cases,14 this Court should

direct that the sufficiency of section 1981 claims after

Patterson be assessed in the first instance by the lower

courts.

Resolution of the Patterson issues in this Court is

not required by the usual practice of deciding cases on

statutory rather than constitutional grounds. As the

14 Bhandari v. First National Bank of Commerce. 106 L. Ed.

2d 558 (1989); Pullman Standard v. Swint, 58 U.S.L.W. 3288 (1989);

Swint v. Pullman Standard. 58 U.S.L.W. 3288 (1989).

15

briefs of the parties make clear, the merits of the

question presented by the petition raise both a non

constitutional and a constitutional issue. We argue, first,

that ordinary principles of collateral estoppel simply do

not apply in this case, that reversal for a jury trial would

be required even if the right to jury trial at issue were

statutory rather than constitutional. (See P. Br. 41-45).

The determination whether collateral estoppel would be

inapplicable to a statutory right to trial by jury, of course,

would not be a constitutional question. We argue,

second, that if collateral estoppel would ordinarily apply

in the procedural posture of this case, its application in

this particular case would be inconsistent with the

Seventh Amendment.15 Although this second contention

15 This may well be one of the admittedly uncommon cases in

which it would be appropriate to address the constitutional issue.

The ordinary rule in favor of avoiding constitutional questions

concerns in particular cases presenting "novel" constitutional issues,

Leroy v. Great Western United Corp., 443 U.S. 173, 181 (1979), or

those involving constitutional challenges to statutes. Ashwander v.

(continued...)

16

is of constitutional dimension, it is an issue the Court

need not reach in order to resolve the jury trial question

in our favor.

(1) Discriminatory Discharge. Respondent urges

this Court to hold that all discriminatory discharges are

not actionable under section 1981. If the application of

section 1981 to claims of this sort necessarily gave rise to

a simple rule, either including or excluding all cases that

might be characterized as "discharges," this might be an

issue that could appropriately be resolved at this

juncture. But because of the widely differing events that

may occur when an employee loses his or her job, the 15

15(...continued)

Tennessee Valley Authority. 297 U.S. 288, 346-48 (1936)(Brandeis, J.,

dissenting). In the instant case the constitutional issue has already

been resolved, and repeatedly so, in petitioner’s favor (P. Br. 34-41),

and involves not a potential conflict with a co-equal branch of

government, but this Court’s special responsibility to supervise

compliance with the Seventh Amendment by the lower federal courts.

On the other hand, the complex statutory questions raised by

respondent regarding the meaning of Patterson are entirely novel,

having their origins in a decision less than six months old.

17

application of Patterson and section 1981 to discharges,

like their application to promotions, is complex and fact-

specific.

The mere announcement that an employee is fired

may by itself do no more than terminate a contractual

relationship; if that were all that occurred when a

particular employee was dismissed, such an event might

arguably constitute pure post-formation conduct.16 But

what actually occurs in a discharge case may in fact be

more complex. Having been formally dismissed, the

16 Several post-Patterson cases hold that all racially motivated

discharges are actionable under section 1981. See, e.g., Birdwhistle

v. Kansas Power and Light Co.. 51 FEP Cases 138 (D. Kan. 1989);

Booth v. Terminix International. 1989 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 10618 (D. Kan.

1989). At least where the discharged worker was an "at will"

employee, this conclusion seems consistent with Patterson, since at-

will employment is commonly regarded as "hiring at will". Corbin on

Contracts. § 70 (1952); Martin v. New York Life Ins. Co.. 148 N.Y.

117, 42 N.E. 416,417 (1895). An employer who fires an at-will

employee is not terminating an existing contract, but refusing to

make new additional unilateral contracts. Since, however, at least

some discharges of at-will or other employees are undeniably still

actionable after Patterson, and the instant complaint thus cannot be

dismissed at this juncture, it is not necessary to decide whether all

discharges are still actionable.

18

potential plaintiff, technically already an ex-employee, at

times seeks to get back his or her job, or, perhaps, some

other position at the firm.17 That a dismissed employee

might immediately seek that old job, or some other

position, is hardly surprising; "the victims of

discrimination want jobs, not lawsuits." Ford Motor Co.

v. EEOC. 458 U.S. 219, 231 (1982).18 Since the

announcement of the dismissal, as respondent itself

argues, ends the old contractual relationship, an ex

employee’s renewed efforts to work at the firm constitute

an attempt to make a new contract. If an employer

spurns these overtures of a newly dismissed employee

because he or she is black, that discriminatory act would

17 See, e.g., Jones v. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers. 1989

U.S.Dist. LEXIS 10307 (W.D.Mo. 1989)(discharge claim actionable

under section 1981 because the employee, after being told he was

fired, "requested a different job, offering to sweep floors if necessary,

to stay employed. Defendant refused.").

18 Indeed, petitioner sought reinstatement herein. Joint

Appendix (JA) 13, par 3.

19

quite literally be a "refusal to enter into a contract"

within the very terms of Patterson.19 That would

obviously be so in the case of a dismissed worker who

applied a year later for employment, as occurred in

McDonnell Douglas v. Green. 411 U.S. 792 (1978).

There is no principled basis for treating differently a

dismissed employee who seeks reinstatement, or a new

position, a day, an hour, or a minute after his or her

dismissal. On four occasions prior to Patterson this

Court held actionable under section 1981 the discharge of

a former employee; in each case the employee, after

19 Padilla v. United Air Lines. 716 F. Supp. 485, 490 n. 4 (D.

Colo. 1989)(”Defendant’s refusal to reconsider plaintiff for rehire due

to discriminatory practices is clearly prohibited by § 1981"); Jones

v. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers. 1989 U.S.Dist. LEXIS 10307

(W.D.Mo. 1989)("in refusing on the basis of race to make a new

contract [with the dismissed worker], defendant violated section

1981”).

20

having been told of the dismissal decision, had taken

steps to induce the employer to restore him to his job.20

Section 1981 would also be applicable to the

termination decision itself if the employer, for racial

reasons, fired a black employee for misconduct for which

white employees were or would have been disciplined in

a less harsh manner. Such discriminatory disciplinary

practices would violate the last clause of section 1981, a

provision not at issue in Patterson, which requires that

blacks "shall be subject to like punishment . . . and to no

other" as whites. The equal punishment clause, on the

other hand, would have no application to an employer

who, with no pretense of disciplinary motive, selected

employees for discharge on the basis of race.

20 McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.. 427 U.S.

273, 275 (1976)(grievance); Delaware State College v. Ricks. 449

U.S. 250, 252 (1980)(appeal of termination decision); St. Francis

College v. Al-Khazraji, 481 U.S. 604, 606 (1987)(appeal of

termination decision); Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656,

664 (1987)(grievance).

21

The complaint in this case, filed almost five years

before Patterson, understandably does not address

specifically all of the additional subsidiary facts that may

be relevant, or even critical, after Patterson. The

complaint does allege that respondent, prior to dismissing

petitioner for an alleged violation of company rules, had

chosen not to discharge whites "who have committed

more serious violations of the company’s rules" than had

petitioner. JA 8, par. 15. This claim clearly falls within

the equal punishment clause of section 1981. The

complaint does not indicate, on the other hand, what

petitioner may have said to company officials after the

initial notice to petitioner that he had been dismissed;

affidavits submitted by respondent indicate that there

were at least two subsequent meetings between those

officials and petitioner before petitioner finally left the

22

plant.21 Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

petitioner was not required in his 1984 complaint "to set

forth specific facts to support [his] allegations of

discrimination," or to anticipate any additional

requirements that might follow from this Court’s 1989

decision in Patterson. Conley v. Gibson. 355 U.S. 41, 47-

48 (1957).

(2) Retaliation. Respondent urges this Court to

hold that no form of retaliation is ever prohibited by

section 1981, arguing that all retaliation constitutes post

formation conduct. (P. Br. 17-19). The application of

section 1981 to retaliation claims raises a large number

of different legal issues, because of the wide variety of

circumstances in which some form of race related

21 Petitioner testified that while he was operating his machine

Larry Miller told him of the termination. Tr. 143. Subsequently

petitioner apparently met both with A1 Duquenne, the production

superintendent, and then with the Employee Relations Department.

Affidavit of A1 Duquenne, p. 3.

23

retaliation might occur. We do not undertake to

speculate as to what all those circumstances might be, or

to analyze how section 1981, and Patterson, might be

applied in each. It is sufficient at this juncture to

observe that there are at least several types of retaliatory

actions that would undoubtedly still be actionable in the

wake of Patterson.

Section 1981 would certainly prevent an employer

from punishing employees because they insisted, in

compliance with section 1981 itself, on hiring in a racially

non-discriminatory manner, or because they objected to

discriminatory hiring practices forbidden by section 1981.

The section 1981 prohibition against discrimination in the

making of contracts includes within its penumbra

protection for those who comply with or protest

24

violations of that statutory command.22 Second, as this

Court noted in Patterson, the equal enforcement clause

of section 1981 "covers wholly private efforts to impede

access to the courts or obstruct nonjudicial methods of

adjudicating disputes about the force of binding

obligations." 105 L.Ed. 2d at 151 (emphasis added).

Thus the enforcement clause would be violated if a

racially motivated employer had a practice of retaliating

against any black employees who sought to enforce their

contract rights. Third, section 1981 would by its own

terms apply to racially motivated efforts of a third party

to interfere with efforts by a black to make a contract

with a new employer, including efforts triggered by a

racially based retaliatory motive. Fourth, racially

motivated retaliation against an individual for seeking to

22 Malhotra v. Cotter & Co.. 50 FEP Cases 1474 (7th Cir. 1989)

(Cudahy, J., concurring); English v. General Development Corp., 50

FEP Cas. 825, 826-28 (N.D. 111. 1989).

25

file suit or give evidence would violate the right

guaranteed by section 1981 "to sue, be parties, [or] give

evidence."

Racially motivated retaliation against individuals

who file Title VII charges violates, at the least, the

statutory rights to sue and give evidence. As this Court

stressed in Patterson, the filing of a Title VII charge is a

prerequisite to the commencement of a Title VII lawsuit;

section 1981’s protection of the right to bring that or any

other lawsuit necessarily encompasses protection of the

steps that are legally required in order to maintain such

litigation. In addition, Title VII requires that any

individual filing a Title VII charge submit an allegation

"in writing under oath." 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b). The

submission of such a sworn statement, setting forth the

26

details and basis of a claimant’s charge, is protected by

the section 1981 guarantee of an equal right to give

evidence.

Respondent urges that section 1981 does not apply

to any form of retaliation related to Title VII because

Title VII itself did not exist when section 1981 was first

enacted. (R. Br. 17-18). But the language of section

1981 is not limited to the right to sue under, or give

evidence in connection with, statutes that had been

adopted prior to 1866. The Congress which enacted

section 1981 certainly intended to give blacks a right to

sue under or give evidence relating to whatever new

statutory or common law rights might be established in

the future.

Respondent argues that petitioner failed to allege

that the asserted retaliation was racially motivated. The

supplemental complaint asserted that respondent

27

"retaliated against [petitioner] for filing a charge of

discrimination." (JA 40, par. 29). Respondent contends

that section 1981 would not be violated if an employer

had a practice of retaliating equally against all

individuals, white as well as black, who filed Title VII

charges. That is not a correct interpretation of section

1981, but it would be an extraordinarily strained reading

of the complaint in this case to construe it as asserting

the existence of such a uniform, race-neutral retaliation

policy on the part of respondent. The more plausible

reading of the complaint, which charges respondent with

favoring whites over blacks in a variety of different ways,

is as alleging respondent retaliated because a black had

filed a Title VII charge. If respondent had any doubt

about the precise nature of this claim, liberal pretrial

procedures were available to resolve the matter. Conley

v. Gibson. 355 U.S. at 47-48.

28

(3) Retroactivity. Respondent urges the Court to

adopt a per se rule that Patterson will be applied

retroactively to all cases pending on June 15, 1989.

Whether a civil case should be applied retroactively

depends on a number of different circumstances spelled

out in Chevron Oil Co. v. Huson. 404 U.S. 97, 106-08

(1971).

The criteria set forth in Chevron often do not

yield a single rule applicable to all cases and every

conceivable circumstance. Central to the Chevron

analysis is whether a new decision "overrul[ed] clear past

precedent on which litigants may have relied." 404 U.S.

at 106. Thus the appropriateness of retroactivity in a

given case will often depend, at least in part, on the

precise nature of the claim, on the date when the case

was filed, and on the state of the law on that date in the

relevant circuit or district court. Compare Goodman v.

29

Lukens Steel Co.. 482 U.S. 656, 663 (1987) (retroactive

application of Wilson v, Garcia. 471 U.S. 261 (1985),

appropriate because there was not a clear Third Circuit

rule to the contrary when the suit was filed in 1973) with

St. Francis College v. Al-Khazraii. 481 U.S. 604, 608-09

(1985)(retroactive application of Wilson not appropriate

because there was clear Third Circuit precedent to the

contrary when the suit was filed in 1980).

The appropriateness of retroactive application of

Patterson will thus depend, at least in part, on the

specific circumstances of each case. Defendants have

sought to rely on Patterson in a variety of different types

of cases, including claims alleging racially discriminatory

promotions, demotions, transfers, discharges, and

retaliation. The reigning law in each circuit with regard

to each of these types of claims, and the date on which

any controlling circuit decision was issued, vary widely, as

30

do the dates on which each of the still pending section

1981 actions was filed. The differences among the lower

courts regarding retroactive application of Patterson

reflects differences in the relevant circuit court law at the

times when those various suits were initiated. See, e.g..

Thomas v. Beech Aircraft Corp., 1989 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

11284 (D. Kan. 1989)(denying retroactive application of

Patterson because application of section 1981 to

discharge cases was "universally recognized" by Tenth

Circuit precedent prior to Patterson).

Resolution of the retroactivity issue in this

particular case must begin, at least, with an assessment of

the relevant Fourth Circuit precedent as of December 6,

1984, the date on which the instant action was

commenced. By that point in time the Fourth Circuit

had held that racially motivated discharges were

31

actionable under section 1981;23 the status of precedent

in that circuit regarding section 1981 retaliation claims is

less clear. In any event, St. Francis College and

Goodman indicate that the evaluation of the state of

circuit court precedents on a given date should be made

in the first instance by the particular court of appeals

whose decisions are at issue.

A linchpin of the decision in Patterson was the

majority’s concern that section 1981 not be construed in

a manner that would circumvent or deter resort to the

administrative machinery established by Title VII. But

the petitioner in this case did file a timely Title VII

charge, and thereafter included a Title VII claim in his

complaint. On the other hand, the complaint alleges, the

respondent attempted to prevent utilization of the Title

VII administrative process by retaliating against petitioner

23 Pope v. City of Hickory. N.C.. 679 F. 2d 20 (4th Cir. 1982).

32

for having invoked it. In the courts below respondent

repeatedly argued that a plaintiff could not pursue a

section 1981 claim unless he or she withdrew any related

Title VII claim; respondent actually prevailed on this

theory in the district court. In this Court, respondent

takes the opposite approach, arguing that petitioner’s

section 1981 claims should be dismissed lest a plaintiff

like petitioner voluntarily ignore the "well-crafted

procedures" of Title VII. (R. Br. 15.) But in the courts

below, and, allegedly, when the administrative charge was

filed, it was respondent who attempted, unsuccessfully, to

force petitioner to forsake those very procedures. For

respondent to now prevail by invoking the sanctity of the

Title VII procedures which it previously sought to

33

eviscerate would be a perversion of the rationale of

Patterson.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

RONALD L. ELLIS

ERIC SCHNAPPER

JUDITH REED*

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

PENDA D. HAIR

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

Suite 301

1275 K Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682 1300

PAMELA S. KARLAN

University of Virginia

School of Law

34

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

Attorneys for Petitioner

* Counsel of Record

November 1989

35