Triangle Improvement Council v. Ritchie Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Triangle Improvement Council v. Ritchie Brief for Appellants, 1969. 8f32fc7d-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96c81945-0950-471b-b60d-1a45f6aeee93/triangle-improvement-council-v-ritchie-brief-for-appellants. Accessed March 05, 2026.

Copied!

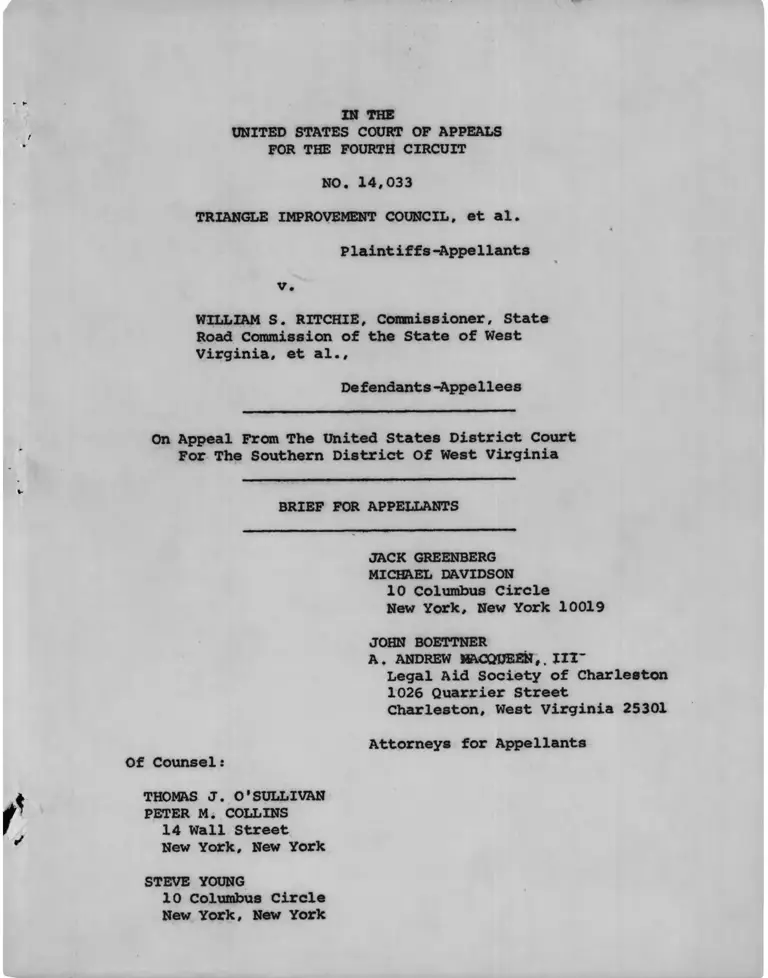

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 14,033

TRIANGLE IMPROVEMENT COUNCIL, et al.

P laint if fs-Appe Hants

v.

WILLIAM S. RITCHIE, Commissioner, State

Road Commission of the State of West

Virginia, et al.,

Defendants -Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of West Virginia

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

MICHAEL DAVIDSON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN BOETTNER

A. ANDREW HACQUEEN,. Ill’

Legal Aid Society of Charleston

1026 Quarrier Street

Charleston, West Virginia 25301

Attorneys for Appellants

Of Counsel:

THOMAS J. O'SULLIVAN

PETER M. COLLINS

14 Wall Street

New York, New York

STEVE YOUNG

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Cases..................................

Statement of Issues Presented for Review........

Statement of the Case ...........................1

Statement of Facts

1. Charleston, West Virginia and

the Triangle.......................... 9

2. The Highway Planning Process .......... 12

3. The Current Status of 1 -77.............. 14

4. The Relocation Amendments to the . . . ;

Federal-Aid Highway Act.................. 17

5. Department Regulations and Inter

pretations Concerning the 1968

Relocation Amendments.................... 18

6. The Decision Not to Require a

Relocation Plan.......................... 21

7. Federal Highway Officials Know

That the Supply of Relocation

Housing is Inadequate.................... 24

8. The Belatedly Contrived "Triangle

Area Relocation Program Plan."

Page

26

Argument

Page.

I. THE 1968 RELOCATION AMENDMENTS

REQUIRE ADEQUATE RELOCATION

HOUSING FOR ALL PERSONS DIS

PLACED AFTER THEIR ENACTMENT.......... 29

1. The Canons of Construction........ 30

2. The 1968 Relocation Amend

ments Are Remedial and Should

Be Liberally Construed............ 31

3 . Any Interpretation Which De

lays the Full and Immediate

Effectiveness of the 1968

Amendments Should be Rejected . . . 37

4. The District Court Erred by

Relying Exclusively on an

Interpretation of a Regula

tion Which Conflicts With The

Remedial Statutory Scheme and

the Regulations.................. 42

5. The State Road Commission Is

Obliged to Assure the Avail

ability of Relocation Housing

For All persons Displaced

After the Enactment of the

1968 Amendments.................. 45

6. The Department of Transporta

tion is Required to Monitor

State Highway Departments And

Assure That No Persons Are

Displaced After the Enactment

of the 1968 Relocation Amend

ments Unless Relocation Housing

is Available 47

Paqe

II. FEDERAL AND STATE HIGHWAY OFFICIALS

HAVE FAILED TO COMPLY WITH THE RE

LOCATION AMENDMENTS TO THE FEDERAL-

AID HIGHWAY ACT AND THE DEPARTMENT

OF TRANSPORTATION'S RELOCATION REG

ULATIONS .............................. 52

1. The District Court Applied

Incorrect Standards of Review . . . 52

2 . The Department Approved the

Srate Road Commission's Assur

ances of the Adequacy of the

State's Relocation program

"Without Observance of Proce

dure Required By Statute" ........ 61

3. The Department Made No Findings

to Support Its Determination

That Relocation Assurances Were

Satisfactory...................... 66

4. The Department's Determination

of the Acceptability of State

Road Commission's Assurances

Was Unsupported by Substantial

Evidence, Arbitrary, and Unlaw

ful.............................. 67

5. Defendants Failed to Consider

Factors, Such as Racial Dis

crimination, Which Are Essential

to a Rational Decision.......... 69

III. THE DISPLACEMENT OF BLACKS IN A DIS

CRIMINATORY HOUSING MARKET WITHOUT

ADEQUATE GOVERNMENTAL MEASURES TO

ASSURE NON-DISCRIMINATORY RELOCATION

HOUSING DEPRIVES DISPLACED BLACKS OF

THE EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAWS . . . 74

Conclusion..................................... 78

TABLE OF CASES

Arr?.ngton v. City of Fairfield,

414 F.2d 687 (5th Cir. 1969) 75, 77

Bowles v. Seminole Rock Co. 325 U.S. 410 30

Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk,

397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968) 76

Charlton v. United States, 412 F.2d 390

(3d Cir. 1969) 56, 58

City of Chicago v. F.P.C.,!38Q F.2d 624

(D.C. Cir. 1967) 71

Michigan Consolidated Gas Co. v. F.P.C.,

283 F.2d 204 (D.C. Cir. i960), cert.

denied, 364 U.S. 913 (1950) 70

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment

Agency, 395 F.2d 920 (2d Cir. 1968) 70, 75, 77

Road Review League v. Boyd 270 F.Supp. 650

(S.D.N.Y. 1967) 60

Saginaw Transfer Co. v. United States,

275 F.Supp. 585 (E.D. Mich. 1967) 67

Scenic Hudson Preservation Conf. v. F.P.C.,

354 F .2d 608 (2d Cir. 1965), cert, denied,

384 U.S. 941 (1966) 70, 73

Scott v. United States 160 Ct. Cl. 152 (1963) 58

S.E.C. v. Chenery Corp., 318 U.S. 80 (1943) 66

Service v. Dulles 354 U.S. 363 (1957) 64

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of

Durham, 393 U.S. 268 (1969) 30

Page

i

Page

Udall v. Taliman, 380 U.S. 1 (1965) 30, 45

Unifcfed States v. Davison Fuel and

Dock Company, 371 F.2d 705 (4th Cir. 1967) 31

United States v. An Article of Drug,

394 U.S. 784 (1969) 31

Western Addition Community Organization

v. Weaver 294 F.Supp. 433, 436 (N.D.

Cal. 1968) 47, 59, 60

Wirtz v. T.T. Peat Humus Co., 373 F.2d

(4th Cir.), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 834

(1967) 31

STATUTES

5 U.S.C. <5701 et seq. 6, 56t57, 62

23 U.S.C. <S101 et seq. 2, 6, 12-13,

17-18, 34, 36,

39-42, 47, 49, 62

42 U.S .C. §1455 (c) (2) 47

42 U.S.C. §3608(c)

REGULATIONS

71-72

IM 80-1-68 18-20, 22, 28,

42-44, 61, 73

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental

Relations, Relocation: Unequal Treat

ment of People and Businesses D.i?'.placed

by Government (1965) 33

Highway Relocation Assistance Study,

90th Cong. 1st Sees. (1957) 34, 38

Jaffa, judicial Control of Administrative

Action (1965) 45

Progress and Protest, The Architectural

Forum, Vol. 131, No. 4

Select Committee on Real Property Acquisi-

tion, Study of Compensation and Assistance

for Persons Affected by Real property

Acquisition in Federal end Federally As

sisted Programs, 88th Cong., 2nd Seas.(1964) 33

Note, The Federal Courts and Urban Renewal,

69 Colum. L. Rev. 472 (.1969)

Page

58

Statement of Issues presented for Review

1. Whether the district court erred in deciding

that families and individuals who are dis

placed, after August 23, 1968, by the con

struction of a federally aided interstate

highway are not entitled to the full pro

tection of the 1968 relocation amendments

to the Federal-Aid Highway Act, 23 U.S.C.

§501 et seq., simply because federal author

ization to acqiiire their residences preceded

August 23, 1968, the effective date of the

relocation amendments.

2. Whether, assuming that the first issue is

decided in favor of plaintiffs-appellants,

defendant federal and state highway offi

cials have failed to comply with the re

location amendments to the Federal-Ard

Highway Act, 23 U.S.C. §501 et_seg.., the

affirmative action requirements of the

Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. 3608(c), and

the relocation regulations of the Depart

ment of Transportation.

iv

3. Whether defendant federal and state

highway officials are denying the

equal protection of the laws to poor

black residents of Charleston, West

Virginia, by removing them from their

homes and forcing them to find re

placement housing in a racially dis

criminatory housing market without

adequately assuring that suitable

relocation housing is available on a

non-discriminatory basis.

v

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 14,033

TRIANGLE IMPROVEMENT COUNCIL, et al.

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

WILLIAM S. RITCHIE, Commissioner, State

Road Commission of the State of West

Virginia, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

The Triangle Improvement Council, an organization

representing residents of Charleston, West Virginia's

1/

black ghetto, the Triangle, and individual residents

of this ghetto, initiated this class action to protect

themselves and their neighborhood against the destructive

effects of an interstate highway which defendant federal

and state highway officials plan to construct through

the Triangle. The principal defendants are federal offi

cials responsible for the administration of the federal

I/ One plaintiff is white. In accordance with Rule 22(d)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, plaintiffs-

appellants will be referred to by the name of the

organizational plaintiff, the Triangle Improvement

Council.

aid highway program, and state officials responsible for

the planning and construction of highways in We3t Virginia.

As neither federal nor state highway officials

have established procedures of receiving, investigating,

and resolving administrative complaints, the Triangle

Improvement Council began this action directly in federal

2/

court. The complaint, filed December 3, 1968, alleged

that: (1) the public hearing on the highway t?as inade

quate; (2) defendants failed to consider, as required,

the adverse social effects of the highway; (3) the impact

of the highway on Charleston's black community is dis

criminatory? and (4) defendants are failing to comply

with the relocation requirements of the Federal-Aid

Highway Act, 23 U.S.C. §501 et seq. (R.V.I, pp. 5-18).

In response, federal and state defendants objected

to both the standing of the Triangle Improvement Council

and the individual complainants to raise the claims in

this lawsuit, and the district court’s jurisdication to

review the actions of the Department of Transportation

2 / At trial, a Department of Transportation official

testified that he kn&w of no complaint procedure.

All he could recommend to anyone with a complaint

is that he write to hi? Congressman or the Presi

dent (R.V.II, p. 139).

-2

and the West Virginia State Road Commission. They also

denied the complaint * a specific factual allegations

3/

(R.V.I, pp. 19-30).

At first, federal and state defendants voluntarily

agreed to halt displacement activities in the Triangle.

When it appeared that the agreement was no longer opera

tive, the Triangle Improvement Council moved for a tem

porary restraining order halting work on the highway

pending a final determination of the action. Relevant

documents were subpoenaed to the hearing on the temporary

restraining order. On March 10, 1969 the district court

quashed the subpoenas and denied the motion for a tem

porary restraining order (R.V.I, p. 35).

The district court then scheduled am April 1,

1959 hearing on the Triangle Improvement Council's

motion for a preliminary injunction. To prepare for the

hearing, the Triangle Improvement Council promptly noticed

the depositions of federal and state highway officials.

Both federal and state officials moved to quash the depo

sition subpoenas and the district court granted the motions

to quash on March 17, 1969. (Ibid). Still seeking the

3/ The federal and state answers were filed May 5 and 8,

1969, respectively, after the April 2-3, 1959 eviden

tiary hearing.

-3-

opportunity for some discovery prior to the hearing, the

Triangle Improvement Council filed motions to produce

and inspect documents (R.V.I, p. 36). These motions were

denied on March 23, 1969, at which time the district

court also quashed subpoenas isstiad on March 26, 1S6S for

the purpose of requiring production of documents at the

hearing itself. (Ibid) The district court did instruct

defendants to bring "all relevant material" to the hearing

which was set over until April 2, 1969 (Ibid.). Apparently,

the definition of relevancy was left to defendants to

determine. At the evidentiary hearing on April 2-3, 1969,

the district court, presumably satirically but nevertheless

accurately, characterized his denial of discovery as "?in-

oori3cionable" (R.V.II, p. 58). In advance of trial, the

district court also restricted the evidence • the consti

tutional and statutory issues concerning relocation (R.V.

I, p. 35).

A hostile environment pervaded the April 2-3

hearing. Throughout the hearing the district court in

quired into the livelihood of counsel and witnesses for

the Triangle Improvement Council (e.g., F..V.II, pp. 3-7).

As local counsel for the Triangle Improvement Council are

employed by a legal aid society which the Office of Economic

-4-

Opportunity funds, and as they are challenging the legality

of the administration of a federally aided program, the

district court felt prompted to disparage the litigation

as a "looking glass war" (R.V.XX, pp» 3, 7). The court

unrestrainedly commented that federal financing of legal

challenges to federally aided programs is "frightening",

" a matter of concern to me not only as a judge but as

an individual", "bureaucracy gone mad", and "ridiculous"

(R.V.II, pp. 427-28). He termed the litigation a "gambit"

tJX.V.II, p. 50), and called upon the local bar association

to reconsider its support of the Legal Aid Society because

the Society, in the court's opinion, was "not fulfilling

its classic role and responsibility" (R.V.II, p. 428).

At the conclusion of the hearing, and in response

to the court * s suggestion, the Triangle Improvement Couxicil

agreed to submit the case for a decision on the merits

without a further evidentiary hearing (R.V.II, pp. 424-25).

This was done simply because the Council had no confidence

that the district court would allow any more latitude for

discovery prior to a final evidentiary hearing than the

coiirt allowed prior to the preliminary evidentiary hearing.

On July 2, 1969, the district court rendered judg

ment on the merits. The court decided two issues favorably

-5-

for the Triangle Improvement Council:standing and review-

ability. The court concluded that the relocation amend

ments to the Federal Aid Highway Act, 23 U.S.C. §501

et seg., "clearly were intended to protect persons such

as the plaintiffs in this matter," and that the Triangle

Improvement Council and individual residents have standing

to challenge the failure to comply with these amendments

(R.V.I, pp. 43-44). The court also concluded that the

administrative decisions involved in this litigation are

reviewable under the Administrative procedure Act, 5 U.S.C.

§701 et seg. (R.V.I, pp. 42-43).

On the merits, however, the district court ordered

dismissal of the complaint (R.V.I, p. 51). The court sus

tained federal and state defendants* interpretation of

the 1968 relocation amendments to the Federal Aid Highway

Act, 23 U.S.C. 501 et seg. That interpretation excludes

from the Act's protection persons displaced after the en-

iP

actment of the 1968 amendments the Department's "auth

orization" to acquire their homes preceded August 23,

1968.

Consequently, residents of Triangle, most of whom

had not been displaced and most of whose homes had not

even been acquired as of August 23, 1968 were not entitled

-6-

to the protection of the relocation amendments simply

because "authorization” to acquire their homes preceded

August 23, 1968 (R.V.I, pp. 46-47).

The district court also agreed with the Depart

ment's and State Road Commission's contention that —

even though they are not required to comply with the 1968

relocation amendments - they were nsJcing "a sincere ef

fort" to comply (R.V.I, p. 48). Beyond expressing con

fidence in defendants' sincerity, the court limited its

review to determining whether federal and state highway

officials were in "substantial compliance" with the

governing statutes and regulations (Ibid). In deciding

whether or not "substantial compliance" was present, the

court relied heavily on defendants' oral assurances to

the court during the course of the trial that relocation

activities would be lawfully conducted. The court simply

"assumed" that these assurances were given "in good faith"

(R.V.I, p. 49). The only specific evidentiary finding

which the court made concerning the availability of re

location housing was that "there is ample public housing

in the Charleston area tc accomodate the limited number

of individuals remaining in the 1̂ -77 corridor in the

Triangle area (R.V.I, p. 50).

-7

The court also dismissed the Triangle Improve

ment Council's constitutional claim that the Fifth and

Fourteenth Amendments prohibit displacing poor blacks in

a discriminatory housing market without assuring that

non-discriminatory relocation housing is available.

Again the court relied on "representations" and "assur

ances" to the court by state and federal highway officials

that they would not discriminate (R.V.I, p. 49). The

court also declared that it was "satisified from the evi

dence that the subject displacees from the 1-77 corridor

in the Triangle ar&a can obtain housing within the range

of their economic means without racial discrimination

which would be of such a nature as to raise federal con

stitutional problems" (R.V.I, pp. 49-50). In the court's

view, the problem was poverty and not race (R.V.I, p. 50).

An order dismissing the complaint was entered

July 18, 1969 (R.V.I, p. 52). On August 25, 1969 the

Triangle Improvement Council filed a notice of appeal

(R.V.I, p. 54), and received permission to appeal in

forma pauperis.

-8-

Statement of Facts

1. Charleston. West Virginia and the Triangle

Charleston, West Virginia has much in common with

other American cities. It is a city in crisis. This

case concerns two aspects of this crisislj race and

housing and the way in which highway planners by

slighting federal law and regulations exacerbate the

crisis.

According to studies undertaken for Charleston's

± yCommunity Renewal Program, a substantial number of

Charleston’s residents live in housing which is struc

turally substandard, beyond their economic means, or

overcrowded (Pit. Exh. No. 14, p. I-C-8). Approximately

4800 of Charleston's 26000 housing units require major

rehabilitation or clearance (Ibid). Over 8000 of these

households pay over 25% of their incomes for rent (Pit.

Exh. No. 16, p. 1-23). Even with excessive rent payments

approximately 3800 households are unable to rent stand

ard housing (Ibid). Typically, this burden falls most

heavily on the very poor (Ibid).

4 / The Community Renewal Report in evidence is a "final

draft report" prepared by the Charleston Municipal

Planning Commission and a planning and development

consultant firm pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1453(d).

The Report analyzes, inter alia. Charleston’s

housing problem.

-9-

While these conditions have victimized both

poor whites and blacks in Charleston, as a group blacks

have suffered most of all (Pit. Exh. Mo. 14, I-D-25),

for the simple reason that blacks are poorer as a

jl/group than whites. Income differentials however,

alone do not account for all of the difficulties which

blacks have in obtaining decent housing. Racial dis

crimination in housing also seriously impedes their

ability to find standard housing (Pit. Exch. No. 19,

pp I-D-25-27).

The result of these forces is the creation of

black ghettoes. One such ghetto is the Triangle,

an area of Charleston which, as described by the

district court, "is populated predominantly by low-

income families of the negro race." (R.V.I. p. 33).

Charleston's housing problems, and especially

the housing problems of Charleston's blacks, have

been getting worse, not better. The major reason for

5 / in 1966, the average annual household income for

blacks was more than $3,000 below the average

income of-white:.households, a factor resulting

largely from job discrimination (Pit. Exh. No. 14,

p. I-D-6).6 / in the words of the final draft report for the Com

munity Renewal Program: "Negroes have established

a foothold in several of Charleston’s older, run

down neighborhoods and with a segregated pattern

being effectively enforced,new Negro households

are forced to locate on the ever-expandingrfrigge

of these neighborhoods." (Pit. Exh. No. 14,

I-D-25).

-10-

this change is the massive demoliton of homes and

displacement of persons by public projects.

The Community Renewal Program estimated that

total displacements in Charleston between 1S6S-71 will

Highway Construction 1,0S4

Urban Renewal 755

State Capital Expansion 280

Disaster, Condemnation and

Conversion 750

Total Displacements 2,879

Pit. Exh. No. 14, p. I-D-14. Since these figures are

for family units the number of persons displaced is far

greater.

Although blacks form less than 10% of Charleston's

population, nearly 20% of the households to be displaced

are black. Further, most of the black displacees are

Upoor. With the joint handicaps of poverty and race

they must find alternative housing in a market which has

already forced them into substandard, excessively costly,

and overcrowded housing.

Of all the neighborhoods in Charleston, the total^ ^

impact of these projects is most severe in the Triangle.

2 y Nearly 60% of all'black households to be displaced

earn less than $3000 annually. (Pit. Exh. No. 14,

I-D-14-15).

_§_/ An informative account of the Triangle's problems

entitled Progress and Protest has recently been

published in The Architectural Forum, Vol. 131,

No. 4, November issue.

-11-

The West Virginia Water Company has acquired land in

the Triangle, displacing 243 people (R.V.I., p. 73).

An urban renewal project will displace 1500 persons

(R.V.I. p. 74). The highways, 1-77 the subject of

this litigation will displace 300 more people in the

Triangle. There are approximately 2000 residents in

the Triangle (R.V.I., p. ). Obviously not many will

be left in what was West Virginia's largest black com

munity, when displacement activities are completed.

2. The Highway Planning Process

1-77 is being constructed as part of the inter-

state highway system. The first statutory step m

highway planning is a State's submission to the

Secretary of Transportation of general programs for

highway projects. 23 U.S.C. §105. Following program

approval by the Secretary the route selection process

begins. During this phase, the public hearing required

by 23 U.S.C. §128 is held, the state highway department

selects a route and a request is made for federal route

q / The responsible federal agency is the Department of

Transportation (acting through the Federal Highway

Administration and the Bureau of Public Roads),

;and the governing federal statute is the Federal

Aid Highway Act, 23 U.S.C. §101 et seg. The reg

ulations are found partly in 23 C.F.R., but mostly

in policy and procedure memoranda and circular

memoranda issued by the Department of Transporta

tion.

-12-

approval. Neither program approval nor route approval

constitutes a contractual obligation by the Federal

government to finance right of way acquisition cr

actual construction.

The approvals which commit the federal government

to pay 90% of the costs of interstate highway construc

tion are approvals of plans, specifications, and estim-

in /ates for proposed projects. 23 U.S.C. §106(a).

These approvals are significant to the relocation ques

tion, as the Secretary is obliged to require"satisfac-

tory assurances" of the availability of adequate reloca

tion before he may approve projects under Section 10S.

23 U.S.C. §502.

In the past "plans, specifications and estimates"

11/were required for actual construction only since

costs of acquiring right of way were ineligible for

federal contributions. 42 Stat. 212. Thereafter when

acquisition costs became eligible for federal contribu

tions, 58 Stat. 838, the submission and approval of plans

specifications, and estimates were administratively

'{777 The term "project"means an undertaking to construct

a particular portion of a highway. 23 U.S.C.§101.

1 1 / The phrase "plans, specifications, and estimates"

appears in the first federal highway act, the

Federal Aid Road Act of 1916. 39 Stat. 357.

-13-

divided into two major stages: the right of way ac-

quisition stage and the construction stage.

Policy and Procedure Memorandum 21-5. Following the

approval of plans, specifications, and estimates for

a given stage, federal and state highway officials

enter into project agreements limited to such stage.

Policy and Procedure Memorandum 21-7. The approval of

the construction stage is the final approval given

by the Department of Transportation.

3• The Current Status of 1-77.

The West Virginia State Road Commission selected

the route of 1-77 which received federal approval on

TuL/August 31, 1964.

The portion of 1-77 routed through the Triangle

consists of two"projects". In 1966 and 1967 federal

highway officials approved state plans, specifications,

and estimates for right of way acquisition and author

ized acquisition of right of way for these projects.

These federal authorizations completed the first stage

of federal approvals required for the two projects in

the Triangle.

] 2 / Right of way clearance is considered part of theconstruction stage. Policy and Procedure Memorandum

21- 12 .

1 3 / As stated above, the approval of route location

did not commit the federal government to pay

right of way and construction costs.

-14-

Further federal approvals remain, however, before

1-77 is actually constructed through the Triangle. As

of the time of trial, the State Road Commission had not

submitted plans, specifications, and estimates for con

struction. (R.V.I. p. 19). Until these are submitted

and approved, the federal government is under no con

tractual obligation to pay for the construction of

1-77. The administrative process of approving 1-77

has begun; it has not been completed.

Within the Triangle, the acquisition program

had barely begun by August 23, 1968, the effective date

of the 1968 relocation amendments. Of the 65 parcels

to be acquired within the Triangle, only ftibe had been

optioned to the State Road Commission prior to that

date. Thereafter, nine additional parcels have been

ootioned to the State Road Commission and one condemna

tion action begun (Pit. Exh. No. 4).

Outside the Triangle, the acquisition program

appears to have been more extensive. On one project

several hundred properties had been acquired over the

two-mile length of the project as of the time of trial

(R.V. Ill, p. 28). It was estimated that 200 properties

had been acquired on the other project. The state right

of way official could not recall the number of parcels

acquired as of August 23, 1968.

Concerning the displacement of people, the

-15-

state's right of way officer testified as to the num

ber of persons remaining to be relocated as of February

28, 1369. In one project 913 persons had already been

displaced and 380 persons remained to be displaced. In

the other project 401 persons had already been dis

placed and 496 persons remained to be displaced. The

federal right of way officer admitted that the remain

ing displacement on that project was "substantial"

(R.V. II, p. 133). Neither federal nor state right of

way officers were able to testify as to the extent of

l A /displacement as of August 23, 1968.

In the Triangle, a substantially smaller prop

ortion of people had been displaced as of February 28,

1969. Some 284 persons remained to be dislocated

(R.V.I, p. 41) and only 17 households had moved prior

to the trial (R.V.I. p. 72 ).

The Triangle Improvement Council requested that

defendants furnish information about the number

of persons dislocated as of August 23, 1968, and

the number of persons remaining to be dislocated

as of that date. The court took the request

under advisement, saying that "if I think it is

an operative factor we can do that to supple

ment the record." (R.V. II, p* 130). Apparently,

the district court concluded that the extent of

displacement as of August 23, 1968 was ttofopera-

tive as the court took no action to require

defendants to supplement the record.

-16-

4. The Relocation Amendments to the Federal”

Aid Highway Act.

The first federal highway relocation la\̂ enacted

in 1962; merely required states to provide relocation

information to displacees. However, it did not require

that housing actually be available for dispxaced per

sons. Even if a state knew that relocation resources

1 5 / .were insufficient, neither federal nor state high

way officials were obliged to curtail their displace

ment activities.

(Tbhgress remedied this deficiency in the Federal

Aid Highway Act of 1968. The 1968 amendments not only

required the payment of a variety of relocation allow

ances, 23 U.S.C. §§505-507, but also a program which

assures the actual availability of adequate relocation

housing for displaced persons. 23 U.S.C. §502 and

i i /§508.

15/ The regulations under the 1962 amendment re

quired state highway departments to compile

information about available public and private

housing opportunities. Policy and Procedure

Memorandum 80-5(3)(f)4 and 5.

16/ to satisfy the statute, the supply of "decent,

safe, and sanitary" relocation housing units must

be "equal in number to the number of and avail

able to . . . displaced families* and individuals."

Relocation housing must also be within the fin

ancial means of displaced persons, in areas in

which public and commercial facilities are at least comparable to the facilities previously en

joyed by displacees, and reasonably accessible

to places of employment. 23 U.S.C. §502(3) and

§508 (a) (2) .

-17-

The statute imposes the obligation to assure the

availability of relocation housing on both state and

federal highway officials. Section 508 requires each

state highway department to establish a relocation ad

visory assistance program which must include assur

ances of the availability of adequate relocation hous

ing. Section 502 requires the Secretary of Transportation

to police the adequacy of state highway relocation

programs. That section bars him from approving any

project unless he receives "satisfactory assurances"

from the state highway department that the required

relocation assistance program and adequate relocation

housing will be available. 23 U.S.C. §502.

5. Department Regulations and Interpretations.

Concerning the 1908 Relocation .Amendments

The Department's regulations detail the kind of

assurances which are required before a state highway

department shall be authorized to proceed tfith "any

phase of any project which will cause the displacement

1 2 /of any person . . . IM 80-1-68(5)(a).

Specific, not general, assurances are required.

The key requirement is that state highway departments

TT7 shortly after the enactment of the 1968 amendment

the Department issued Instructional Memoranaum

80-1-68 to govern the administration of the lybo

amendments. The IM was issued pursuant to the

Secretary's rule-making power. 23 U.S.C. §biu.

-18-

prepare relocation plans which present relevant factual

data pertaining to relocation housing problems and

their solution. IM 80-1-68(7).

On the basis of the information in the plan,

federal highway officials must determine whether "the

State's relocation program is realistic and is adequate

to provide orderly, timely, and efficient relocation

of displaced individuals and familifes^to decent, safe

and sanitary housing available to persons without re

gard to race, color, religion or national origin with

minimum hardship on those affected." IM 80-l-68.(2J_.

Although the Department of Transportation's reg

ulations clearly set forth the kind of relocation

assurances required by the Department, the regulations

are an uncertain guide to their applicability to pro

jects authorized prior to the enactment of the 1968

amendments. On the one hand, the regulations state that

they are applicable to "all Federal-aid highway projects

authorized on or before August 23, 1968, on which in

dividuals, [and] families '. . . have not been displaced."

TM 80-1-68(2)(b)(2). On the other hand, paragraph 5(b)

of the regulations states that "(relocation) assur

ances are not required where authorization to acquire

right of way or to commence construction has been given

prior to the issuance of this memorandum." IM 80-1-69 (5j_Jb).

-19-

This latter statement is immediately qualified by

the following proviso in Paragraph 5(b) that "the

State will pick up the sequence at whatever point it

may be in the acquisition program at the time of issu

ance of this memorandum." IM 80-1-58(5? (b)

On February 12, 1959, the Department issued a

circular memorandum ("CM") presumably to clarify re

location procedures on active projects. Federal of

ficials relied extensively in this CM to support

their interpretation of the statute and regulations that

the state was not required to submit a relocation plan.

The CM required the State to undertake relocation plan

ning "on all active projects to the extent that is

reasonable and px*oper." It instructed federal highway

officials to review active projects before issuing

additional authorizations to acquire right-of-way or

begin construction and"to assure himself that the State

has or will make the necessary relocations without un-

l J E t / 1 " -U.' *due hardship to the relocatees." If "a substantial

number" of people remain to be relocated the division

engineer is instructed to require a relocation plan

before issuing an authorization v/hich will result in

displacement.

IQ_/ The text of the February 12, 1969 memorandum is

included in the Statutory Appendix,

-20-

Finally, the circular memorandum concluded by

stating that whether or not a federal obligation exists

to police a state highway department's relocation pro

gram on an active on-going project, "it is the respon

sibility of the State to furnish relocation assistance,

and payments where authorized by State law, in accord

ance with the requirements of the law and the IM".

6. The Decision Not to Require a Relocation Plan.

From this morass of conflicting regulations and

interpretations officials within the Department had to

determine whether to require the State Road Commission

to submit a plan of relocation. The State Road Com

mission submitted general assurances for all of West

Virginia, which the Department of Transportation approved

that displacees from all highway projects will be adequat

ely rehoused (R.V.II, pp. 39-40). However, the federal

officials decided not to require the submission of a

relocation plan to substantiate the State Road Commis

sion's "assurances" for the two projects in the Triangle

or indeed for any interstate projects in Charleston

(R.V.II, p. 358).

The determination by federal officials that the

State need not submit a relocation plan for the 1-77

projects was based iii part upon this interpretation

of Department regulations. Thus the chief federal road

-21-

official in West Virginia testified that "tt)he

specific language of this IM (80-1-68) and the attach

ments thereto preclude the necessity of a requirement

for a relocation plan”. (R.V. I‘i, p* 400). The

federal right of way officer in West Virginia found his

legal support in the provisions of the February 12, 1969

C.M. (R.V. II, pp. 102). While admitting that a "sub

stantial” number of persons remained to be dislocated

(R.V.II, p. 138), the federal right of way officer

nevertheless concluded that a relocation plan was not

required. He interpreted the CM as providing that no

relocation plan was necessary if authorizations to ac

quire right of way had already been issued (R.V.II,p.139).

However, Federal highway officials did not

place sole reliance on their interpretations of law to

justify their failure to require a relocation plan.

The federal right of way officer testified that he was

"satisfied" that the state maintained close surveill

ance of relocation on all projects in Charleston; that

the State at least had "half of a relocation plan ;

that the state had provided general assurances under

paragraph 5a of IM 80-1-63, "so we had a certain amount

of protection here" (R.V.II, pp. 73-74); that his observa

tions of the State's prior experience (under the weaker

1962 relocation amendment)" satisfied me that they can

-22-

relocate the people in the Triangle and other areas"

(Id. at 75); and that he had previously studied re

location problems in Charleston (.Id. at 75-77) ,

though he did not mention that his studies had

demonstrated the "depletion"of housing and "critical”

shortage of relocation housing in Charleston (R.V.I,

pp.67, 70).

-23-

7. Federal Highway Officials Know That The

Supply of Relocation Housing Is Inadequate.

Federal highway officials' expression of satis

faction with state relocation capabilities is strictly

contrary to their own acknowledgment that the supply of

relocation housing in Charleston is inadequate. Early

in 1968, federal officials uncovered serious deficiencies

in the supply of relocation housing. Anticipating the

adoption of the 1969 relocation amendments federal

officials were instructed to review relocation programs

of states within their jurisdiction.

In Charleston, the federal division engineer

requested information from the State Road Commission,

and, independently, the federal right of way officer

mode his own inquiries into the availability of re

location housing. Neither approach revealed the presence

of adequate relocation housing. Indeed, three perceptive

memoranda by the federal right of way officer candidly

reported deficiencies in the supply of relocation housing.

fc.V.I. pp. 60-70). On February 20, 1968, he reported:

It is my opinion that our major area of concern

lies with those people who have incomes over and

above that which would qualify them for public

housing and desire to rent. More specifically,

this area would be defined as families with

average annual incomes of from $5000 to $7500

a year and who do not want to, or cannot, buy

their own home. Urban renewal and public housing

as of little value to our relocation problem in

these cases, and I have reason to believe that

the private housing market is about saturated

presently. (R.V.I. p. 62) # [Emphasis added]

-24-

He underscored his concerns again on February 26, 1968:

It appears that the relocation problem in the

Charleston area, insofar as the State Road

Commission is concerned, could become critieal

in the not too distant future due primarily

to the apparent lack of rental property in the

$60-$90 per month price range. The available

replacement housing in this area is being

depleted and no new sources are available at

this time. (R.V.I. p. 67).

Less than 10 days later, on March 16, 1968 after meeting

with State Road Commission, Federal Housing Administra

tion and Urban Renewal officials, the division right of

way officer again expressed his alarm.

It appears that the Federal Housing Administra

tion programs will provide the only source of

replacement housing in the area. The existing

private market, particularly in low to moderate

priced rentals, is being depleted primarily by

Interstate acquisition. (R.V.I. p. 70).

In Contrast to the federal official's candid and

critical analysis of Charleston's housing problem, the

State Road Commission produced no detailed findings.

Indeed, the federal division engineer so concluded when

he expressed his dissatisfaction with information pro

vided by the State:

In the Charleston area the State did secure

valuable information relative to persons to

be dislocated by a survey which was a valuable

assist in defining the overall problem involved.

It would not be considered, in our opinion, a

complete relocation plan since it did not pro

vide information either factual, estimated or

projected as to the availability of replacement

housing. (R.V.I. p. 58).

Nevertheless, no remedial action was required because, as

— 25-

the federal right of way officer testified, "it was

not considered in our opinion required that they have

a complete one" (Ibid).

At trial, the division engineer was asked whether

the facts described in the right of way officer's

February and March 1968 evaluations had changed during

the year (R.V. II, p. 412). The only change he could

, L9/cite was the availability of rent supplements.

8. The Belatedly Contrived "Triangle Area

Relocation Program Plan" ._____________

Solely in response to this lawsuit, the State

2 Q _ /Road Commission prepared a "relocation plan" for

the Triangle (R.V. II, p. 359). Although the Department

requested and obtained a copy of the completed plan,

the Department oddly enough did not review it (R.V. II,

pp. 389, 116). When the federal right of way official

was asked whether he had "seen" it, he answered only:

Without rent supplements, he testified, "I’m not

at all sure they could have gone through with the

relocation program in the area" (R.V. II, p. 414).

When asked what families who were unable to afford

the housing into which they had been relocated would

do after their limited two year rent supplements

expired, the federal division engineer had no answer.

All he could say was that "there are many other government programs," "I am not a social worker,"

and "I assume you are asking a question which is up

to Congress to answer" (R.V. II, p. 415).

20/ The entire plan is reproduced in the appendix R.V.I.

pp. 71-99. The plan was prepared in late February

1969, nearly three months after this action

began.

-26-

"I have seen it. That's about all" (R.V. II, p.

116).

The plan provides some useful information

about the Triangle residents: the overwhelming

numbers are tenants and poor. Information in the

plan about their ability to obtain relocation housing

is far less adequate. The plan only vaguely asserts

that the majority of Triangle displacees "appear" to be

eligible for public housing.

With respect to private housing the plan

shows that the average monthly rent of the units

available was $90, approximately double the $45-$50

monthly rental now paid by Triangle residents. The

plan was silent on room size of the units and space

needs of Triangle displacees. Though the plan stated

that some 80 rental units are available, no effort was

made to determine whether such units are available to

?l /blacks. When a community worker did survey a 50

unit list furnished by the State Road Commission, she

discovered, upon simple inquiry, that there were landlords

2V The State Road Commission takes the position

that no inquiries concerning racial avail

ability were necessary because Charleston

has a fair housing ordinance. The fair

housing ordinance does not, however, cover

all units (R.V.II, p. 368).

-27-

on that list who would not rent to blacks. She

also discovered that 28 units on the li3t had

already been ranted (R.V.II, p. 285). Her

testimony was not rebutted.

While the plan acknowledges the drastic and

cumulative impact of public projects on the Triangle,

it treats the Triangle in isolation. Although, as

of the time of trial, several hundred people who

lived outside the Triangle also had yet to be dis

placed by the highway alone, no consideration was given

to their needs for replacement housing or the extent

to which they would compete for the housing which

the State Road Commission's plan asserts will be

available for Triangle displacees. Obviously,

Triangle displacees have no priority over other high

way displacees in their search for public or private

housing. The State Road Commission just did not

consider the competition to be "relevant" (R.V.II,

p. 372). In contrast to the State, the Department

of Transportation considers competition for available

units to be highly relevant. IM 80-1-68(7)(b).

-28-

ARGUMENT

I

THE 1968 RELOCATION AMENDMENTS REQUIRE

ADEQUATE RELOCATION HOUSING FOR ALL

PERSONS DISPLACED AFTER THEIR ENACTMENT

The Department and the state Road Commission

claim though they draw no support from the

that they are not required to assure the availability

of relocation housing to Triangle displaces® because

authorizations to acquire right of way in the Triangle

preceded the enactment of the 1968 amendments. For

this proposition, they rely on their interpretation of

the Department's regulations.

The district court sustained their interpretation,

ruling that the agency's determination had "a rational

basis" and that this was all that was needed (Ibid).

However, the court did not suggest what, if anything,

in the history or language of the 1968 amendments sup

ported the Department's interpretation. In terms of the

Triangle, the district court's holding means that persons

22/

who will not be displaced until mid 1970, two years after

22/ The State Road Commission estimates "lead time" for

the highway project is 16 months from February 28,

1969 (R.V.I, p. 74). Construction is estimated to

begin in late 1970 (R.V.II, p. 389).

-29-

the enactment of the 1968 amendments, are not protected

by the relocation amendments because the Department

authorised the acquisition of their homes prior to the

1938 amendment. We submit that the 1968 amendments do

not permit this interpretation.

1. The Canons of Construction

Generally, the question concerning the validity

of an administrative regulation is whether or not the

regulation is "inconsistent" with its underlying statute.

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Ditrham, 393

U.S. 268, 277 (1969). The test is not an unwaivering

one, however.

On the one hand, there are canons of construction

which urge a reviewing court to limit its inquiry and

show "great deference to the interpretation given the

statute by the officers or agency charged with its ad

ministration". Udall v. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1, 16 (1965).

This is especially so when the issue is the validity of

administrative interpretation of an administrative reg

ulation, and not the validity of the regulation itself.

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham. 39?

U.S. 268, 276 (1969); Udall v. Tallman 380 U.S. 1, 16

; Bowles v. Seminole Rock Co., 325 U.P, 410, 413-14

(1945). 30-

On the other hand, if a statute is remedial then

the general canon of construction is that it should be

liberally construed. United States v. An Artj.c_le_.gf_Drug^

394 U.S. 784, 798 (1959). The task of liberal construc

tion is "to effectuate congressional policy". United^

States v. Davison Fuel And Dock Company, 371 F.2d 705

(4th Cir. 19S7). Moreover, exceptions to remedial statutes

should be narrowly construed. As this Court held in

striking down a claim that workers manufacturing peat

moss are not protected by the Fair Labor Standards Act:

Remedial social legislation of this nature is

to be construed liberally in favor of the

workers whom it was designed to protect and

any exemption form its terms must be narrowly

cons tr xied.

Wirtz v. T. T. Feat Humus Co., 373 F.2d (4th Cir.) cert,

denied., 389 U.S. 834 (1967). Accordingly, a reviewing

court should examine the history and purpose of a re

medial statute and approve only those interpretations

which assure protection for people whom the legislature

intended to protect.

2. The 1968 Relocation Amendments are

Remedial and Should be Liberally _

Construed.

The 1968 relocation amendments resulted from *

decade of efforts to reform the interstate highway

-31-

On the other hand, if a statute is remedial then

the general canon cf construction is that it should be

liberally construed. United States v„ An Article of Prng_>

394 U.S. 734, 793 (1959). The task of liberal construc

tion is "to effectuate congressional policy". United_

States v. Davison Fuel And Dock Company. 371 F.2d 705

(4th Cir. 1957). Moreover, exceptions to remedial statutes

should be narrowly construed. As this Court held zn

striking down a claim that workers manufacturing peat

moss are not protected by the Fair Labor Standards Act:

Remedial social legislation of this nature is

to be construed liberally in favor cf the

workers whom it was designed to protect and

any exemption form its terras must be narrowly

construed.

Wirtz V. T. T . Feat Humus Co., 373 F,2d (4th Cir.) cert,

denied., 389 U.S. S34 (1967). Accordingly, a reviewing

covert should examine the history and purpose of a re

medial statute and approve only those interpretations

which assure protection for people whom the legislature

intended to protect.

2. The 1958 Relocation Amendments are

Remedial and Should be Liberally

Construed.

The 1968 relocation amendments resulted from ?

decade of efforts to reform the interstate highway

-31-

program. The history of this effort clearly demonstrates

that the relocation amendments are designed to remedy a

serious national wrong.

Early in the interstate highway program, members

of Congress recognized that the burdens of displacement

were falling on those least able to reestablish themselves.

In support of a 1957 relocation bill. Senator Javits said:

It is our aim to ease in every way the burdens

of moderate arid low-income families which are

most frequently displaced. . . as a result of

major public improvements in which the United

States participates. . .We should do everything

we can toward this objective of humanitarianism

and justice.

103 Cong. Rec. 5316-7 (1957). Senator Javits' concerns

were soon underscored by three successive government

studies. Each expressed alarm at the effects of displace

ment by government programs, and each called for the kind

of remedial action which the 1968 relocation amendments

provide.

The first study was the work of a Select Congres

sional Committee. Its central findings confirmed that

23/

2?./ Indeed the Senate report noted:

"The problem of providing adequate relocation as

sistance to those persons. . .displaced by highway

construction on the Federal Aid system has long

been a subject of the comm:* tteeb* attention. *

1968 U.S. Code Cong. Ad. News 3487.

-32-

displacement caused by federally assisted programs sev

erely disadvantaged the poor and minority groups:

Most displacements affect low or moderate

income families or individuals, for whom

a forced move is a very difficult experi

ence. The problem i3 aggravated for the

elderly, the large family and the nonwhite

displacee. The lack of standard housing

at prices or rents that low or moderate

income families can afford is the most

serious relocation problem.

The committee1s findings were confirmed in a report of

the Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations

which further emphasized that the burdens of displace

ment fall unevenly on the poor and nonwhite. Its reoody.

was the same as the Select Committee’s: mandatory assur-

25/

ance of an adequate supply of standard housing.

In 1566 Congress responded to the reports and

called for a study to determine what action should be

taken to provide additional assistance to highway dis-

placees. Pub. L. 89-74. The report of the Senate Public

24/ Select Committee on Real Property Acquisition,

Study of Compensation and Assistance.f or.Persons.

Afiected by Real property Acquisition in Federal.

and"Federally Assisted programs, 88th Cong., 2nd

Sess., at 106 (1964).

25/ Advisory Commission Intergovernmental Relation®

Relocation: Unequal Treatment of People and_

Businesses Displaced by Government. (1965).

—33 —

Works Committee accompanying the 19G6 highway hill stated

that the operation of 23 U.S.C.§£L33 "has not been fully

satisfactory and effective. . The report further ex

pressed the Committee's concern that "the situation has

worsened as construction of the Interstate System has

moved into heavily developed urban areas.” 1966 U.S.

Code Cong. & Ad. News 3043-4.

The resulting study, Highway Relocation Assistance

Study, 90th Cong., 1st Sess (1967), restated problems which

were already well known. Low and moderate income persons

continued to bear the burden of highway displacements.

Prompt federal action tras necessary "to avoid

the human and economic disasters that can be wrought by

26/involuntary displacement." Id. at 36.

The decade of reform efforts resulted in the

relocation provisions of the Federal Aid Highway Act of

i960, 23 U.S.C. §501 et sag. The committee reports,

floor debate, and language of the 1968 amendments all

confirm v,That the history of the previous decade showed —

that the relocation amendments were truly "remedial".

26/ The urgency of federal action was underscored by the

projection that between July 1, 1967 and June 30,

1970, 146,903 residential units will be displaced by

federally aided highway construction while most of

the right of way for the interstate system will have

been acquired (although not necessarily cleared) by

June 30, 1970. Id. at 45.

-34-

During debate on the Federal-Aid Highway Act of

1968, the importance of adequate relocation was continu

ally restated. The relationship of highway displacement

to urban unrest was very much in the forefront of Con

gressional concern. The principal sponsor of the 1SS8

Act, Senator William Jennings Randolph, spoke of the

urgent need for a comprehensive highway relocation pro

gram:

Today wa are in an \irban society. . . These

dislocations and displacements caused by

urban highways have been the source of much

of the discontent avid unrest in our cities.

114 Cong. Rec. 8037. As Senator Randolph continued, im

mediate action was imperative:

We cannot wait any longer for this program.

There is an urgency about it. I think it

is imperative that we move.

114 Cong Rec. 8038.

Finally, in the text of the 1968 Act itself.

Congress unequivocally established the remedial nature

of the relocation amendments. In a "Declaration of

Policy", Congress declared that "the prompt and equitable

relocation" of persons displaced by the construction of

federally aided highways:

. . .is necessary to insure that a few

individuals do not suffer dispropor

tionate injuries as a result of programs

-35-

designed for the benefit of the public

as a whole.

23 U.S.C. §501.

Finally, there are two special considerations

present which call for statutory interpretations which

give full effect to the remedial purposes of the reloca

tion amendments, and call for close scrutiny of Depart

ment interpretations which restrict the application of

the 1968 amendments.

One eonsideraion is that the wrong which the

relocation amendments seek to remedy is often a consti

tutional wrong. The history of the interstate program

(as revealed by government studies) shows the discrimin

atory burdens placed on the poor and racial minorities.

The custernary deference which courts give to interpreta

tions of administrative agencies has no place where

questions of equal protection are involved.

A second somewhat atypical consideration present

in this case is that the wrong which the federal agency

is directed to correct is one which the agency itself

helped to create. This is not the usual situation in

which a federal agency is set up to administer remedial

legislation designed to regulate the activity of private

-36-

or semi-public parties in the public interest. The agency

here is not the "Department of Relocation" (nor is there

even an individual charged with the sole responsibility

of relocation). The Department of Transportationcs primary

function is that of a road builder: to build the inter

state system, and build it fast. In the process, it has

displaced thousands upon thousands of people (mostly poor

and non-white) who have not been adequately rehoused.

Now it is ordered by Congress to reform itself. Its

steps towards reform if hesitant or faltering should be

closely scrutinized, and any decisions which deny reloc

ation assistance should be severely questioned.

In these circumstances, the district court should

not have deferred, as it did, to the agency's interpreta

tion of its obligations.

3. Any Interpretation Which Delays the Full,

and Immediate Effectiveness of the 1968

Amendments Should be Rejected.

The 1968 amendments were enacted after most of

27/

the damage had been done. If the amendments are to pro

vide any meaningful protection then their full force; must'

2 J / By 1968, approximately 26000 miles of the interstate

system had been constructed. Of the remaining 15,000

miles, approximately 6000 were under construction

and 8500 in engineering design or right of way ac

quisition stages. 1968 U.S. Code Cong. ST Ad Newd 4046.

-37-

be felt immediately.

The Department of Transportation projects that

acquisition of right of v/ay for the entire interstate

system will be virtually complete by June 1970. Highway.

Relocation Assistance Study, p. 45. If the time between

nr.thorizations to acquire right of way and the completion

of actual acquisition of right of way in the Tricingle is

characteristic of the interstate system, then it appears

that substantially all authorizations to acquire right

of way throughout the entire system were issued prior to

the enactment of the 1968 amendments. Accordingly, an

interpretation which denies their full protection to pro

jects on which right of way acquisition was authorized

prior to their enactment renders them virtually meaning

less.

Before a reviewing court looks to an agency inter

pretation of a statute, it should first determine whether

Congress considered and resolved the very issue at stake.

Here Congress clearly adverted to the problem of applic

ability. As a general rule, the relocation amendments

"shall take effect on the date of [their] enactment. . ."

P.L. 90-495 §37. This rule of immediate applicability

is emphasized ir the statute’s definition of a "displaced

-38-

person" to mean:

. .any person who moves from real

property on or after the effective

date of this chapter as a result of

the acquisition or reasonable expect

ation of acquisition of such real

property. . . "

23 U.S.C. §511(3).

*

But, to avoid the type of "inflexibility" which

•

concerned the court below, Congress created a specific

exception to the general rule of applicability. Until

Jrily 1, 1970, the relocation provisions of the Act are

applicable to a state highway department "only to the

extent that such State is able under its laws to comply

with such sections" and thereafter the Act becomes fully

applicable 90-495 §37.,Congress permitted this lim

ited delay to allow states to adopt legislation ̂ author

izing their highway departments to pay increased reloc

ation allowances, and the Department has correctly decided

that this limited delay applies only to relocation payments

and not to the requirement that adequate relocation housing

28/

be available.

Moreover, even as to relocation payments. Congress

sought to expedite the implementation of the 1968 amend-

23/ The Department's ruling is contained in a Circular

Memorandum, December 26, 1968, which is reproduced

in the Statutory Appendix.

-39-

taints by providing full federal reimbursement (not just

a ninety percent contribution) of payments to displacses.

29/

fell'JSly.Z*, 1S7Q. 23 U.S.C. §504a.

Furthermore, Congress has explicitly provided a

mechanism to apply the requirements of the 1968 amend

ments to projects approved prior to their enactment.

Project agreements executed prior to the enactment of u

the 1968 relocation amendments are required to be amended

to include federal reimbursement for the costs of reloc

ation services and payments described in 23 U.S.C. §502

"with respect to property which has not been acquired as

of the date of this chapter." 23 U.S.C. §504(b). The

prevision of funds necessarily entails an obligation to

provide the services described. As the report of the

2 9 / The explanation by the Senate Committee on Public

Works is instructive:

Delay in implementing the relocation program

would inevitably result if the States had to

be given time to enact legislation enabling

them to contribute their usual share of these

relocation payments. Since the great majority

of highway displacements will in fact take place

in the years before 1971, the committee feels

that the 100 percent Federal share during this

period is necessary to the success of the pro

gram.

1968 U.S. Code Concr. Ad. News. 4076.

-40-

Senate Committee on Public Works states:

Subsection (b) would require application of

the requirements of this chapter to any

project for which property had not been

acquired before the enactment of this act.

r *30/

1568 U.S. Code Cong, d. News'.'3523.

The 1968 Congressional determination as to the

applicability of the relocation amendments to previously

approved projects stands in marked contrast.-to it3 deter

mination in 1962 on the same subject. Congress specific

ally prohibited the application of the 196? highway relocation

amendment to projects approved prior to its enactment.

23 U.S.C. §133(e). Likewise, in adopting a similar pro

vision for urban renewal law (which requires the Secretary

of Housing and Urban Development to police the relocation

activities of local agencies). Congress explicitly man

dated that new requirements did not apply to projects in

which HUD had already approved planning grants. Pub. L.

88-560, §305(a).

In short, the 1968 amendments strikingly omit

prohibitions (present in previous highway and circular

urban renewal statutes) against applying their beneficial

30/ The provision of the Senate bill (S. 3418) on which

the committee commented was carried over verbatim

into 23 U.S.C. §504(b). See 114 Cong. Rec. 8028.

-41-

provisions to going projects, and indeed create a mechanism

for retroactive applicability in 23 U.S.C. §504(b). In

view of such clear-cut Congressional intent the court below

erred in holding that Congress could not have intended to

subject previously approved projects to the requirements

of the 1968 amendments (R.V.I, p. 48).

4. The District Court Erred by Relying

Exclusively on an Interpretation of

a Regulation which conflicts with

the Remedial Statutory Scheme and

the Regulations.

A careful examination of the Department's regul

ations reveals a pattern generally consistent with the

remedial statutory scheme and the legislative history.

Nevertheless the district court singled out one peculiar

sentence of the IM and interpreted it to deprive persons

not displaced as of the effective date of the Act of its

benefits. (R.V.I, p. 47).

The first sentence of paragraph 5(b) of W' 8Gr-*r68

states:

The above assurances are not required where

authorization to acquire right-of-way or to

commence construction has been given prior

to the issuance of this memorandum.

The court below interpreted that sentence to mean that

if federal authorization for right of way acquisition

-42-

had been given by August 23, 1968, the relocation amend

ments did not apply. However, the regulations set forth

a consistent rational pattern which contradicts the court's

interpretation of that single sentence. Thus paragraph

2(b)(2) of the IM, which states thfct it applies to "all

Federal-aid highway projects authorized on or before

August 23, 1968, on which individuals. . . have not been

displaced," is wholly consistent with the early applic

ability mandated by Congress in Section 511(3)," Likewise

paragraph 5(a) of the IM goes beyond the words "any pro

ject" of Section 502 and bars authorization of "any phase

of any project which“Will cause the displacement of any

person. . (emphasis added).

The interpretation that the first sentence of 5(b)

means that no assurances are required once right of way

authorization has been given is inconsistent with the

above regulations. Moreover it turns the second sentence

of 5(b) into sheer nonsense:

The State will pick up the sequence at

whatever point it may be in the acquisi

tion program at the time of the issuance

of this memorandum .

Obviously if the "acquisition program" had begun, federal

right of authorizations must have been given earlier, and

-43-

hence the regulations do not establish right of way author

ization as the cut-off time. The district judge made no

attempt to reconcile his reading of the first sentence v/ith

31/

the second. Indeed the federal officials were utterly un

able to render the second sentence intelligible (R.V.II, p.94).

A possible explanation is the lame excuse given by one of-

fic al that the IM was hasty "paste-up" (R.V.II, p. 403).

Moreover, federal officials acted as if that was not. the

proper interpretation of paragraph 5 (b), for they inter

preted the IM to apply to the Triangle projects and required

the state to give paragraph 5(a) assurances (R.V.II, p. 53).

The opinion of the court below did not resolve this appar

ent conflict between his interpretation of 5(b) and the

interpretation given that paragraph by the federal offi

cials. The federal official contended that 5(a) applied

but that the February 12, 1969 CM excused the state from

preparation of a relocation plan. His interpretation of the CM

3 1/ it is possible to read the two sentences as consistent:

Thus where an authorization preceded August 23, 1968,

assurances are not required with respect to that auth

orization. Thus the sentence excuses federal officials

£romnr&opening authorizations already approved, nor

such authorizations, new relocation assurances are

not required. The second sentence means that the IM

applies to going projects where persons have not been

displaced and where additional authorizations are

needed.

-44-

was no more warranted by a reading of the whole CM in

light of the Statute and the Regulations than the district

court was in giving a meaning to paragraph 5(b) which was

directly contrary to the interpretation given to it by

the federal officials who felt that it applied and required

assuances from the state.

In Udall v. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1 (1965) the case relied

on by the district court to susta n the Department's in

terpretation of its obligations, the Court stressed that

the regulation in question had been "consistently construed"

in a certain way by the agency. Id. at 17. Here, the

Department's obligations have not been "consistently con

strued". It may be that federal officials arrived at

their interpretation to avoid the imposition of "another

hair shirt" (R.V.II, p. 410) of additional work. In the

words of Professor Jaffe, agency discretion here may have

been J'a facade for inadequate thinking, failure to face

issues, hidden expediencies, or downright dishonesty."

Jaffe, Judicial Control of Administrative Action 588 (1965).

S . The State Road Commission is Obliged to

Assure the Availability of Relocation

Housing gor All Persons Displaced After

the Enactment of the 1968 Amendments.

The State Road Commission is required to assure

relocation housing for each person it displaces after the

-45

enactment of the 1968 relocation amendments. 23 U.S.C.

§508. This obligation is not related to any particular

stage of project approval, and exists independently of

the Department of Transportation obligation under

Section 502 to police the State's relocation program.

To be clear, the State's obligation to assure

adequate relocation housing runs to each person thi&-

State displaces even if the Department authorised the

acquisition of his home prior to the 1968 amendments,

and even if his home was actually acquired prior to these

amendments.

The State's focus is required to be on people,

not technical concepts of property law. As the Federal

Highway Administrator testified earlier this year before

a Congressional committee:

We read the Federal-Aid Highway Act provisions

to require relocation payments if actual dis

placements had not in fact occured as of the

act's effective date. In other words, persons

still lawfully occupying property at the effec

tive date of the act were entitled to its bene

fits. This Approach has several advantages.

It avoided the difficulties inherent in any

attempt to decide when property was technically

"acquired" as a legal concept, it was easy to

32/ See Circular Memorandum, February 12, 1969, which

is reproduced on the Statutory Appendix.

46 -

administer, and was a rational determination

of the point at which benefits should be pro

vided .

The only question which remains is the extent of the

Department's obligation to police the State's relocation

program.

6• The Department of Transportation is

Required to Monitor State Highway

Departments and Assure That. Ho Per

sons Are Displaced After the Enact

ment of the 1568 Pelocation Amend

ments Unless Relocation Hoxising is

Available.

Congress did not leave the administration of its

remedial highway relocation legislation in the unsuper

vised hands of state highway departments. Just as in the

federal urban renewal law. Congress imposed a duty on a

federal agency to "police", Western Addition Community

Organization v. Weaver, 2S4 F. Supp. 433, 436 (N.D. Cal.

1968), the administration of local relocation programs

in order to assure the availability of relocation housing.

Compare, 42 U.S.C. §1455 (c)(2) and 23 U.S.C. §502.

33/ Hearings on S. 1 Before the Subcommittee on Inter

governmental Relations of the Senate Committee on

Governmental Operations, 91st Cong. 1st Sess., p. 300.

Although the A.dministrator at first spoke of reloca

tion payments, he concluded by speaking broadly of

benefits. There is no basis for reading the reloca

tion amendments to provide an earlier date for payments

than the assurance that relocation housing actually

exists. If anything, assurances of the availability

of relocation housing are required even where payments

are not. (Circular Memorandum, December 26, 196S)

•47

This important duty does not both begin and end

at the time of approving authorisations to acquire prop

erty. It applies to the approval of "any project" which

causes displacement of people, 23 U.S.C. §502, and nec

essarily entails continuing supervision of a state's

performance after approvals are given. The Department's

determination that it may absolve itself of its respon

sibility to assure that displacees are adeqtiately rehoused

is inconsistent with the purpose of the 1968 amendments.

To understand the responsibility of federal high

way officials, it's necessary to look beyond the Depart

ment's regulations and interpretations to the statute

itself. As described earlier, the Department's regula

tions and interpretations lend themselves to confusion

and contradiction. Only the statute, viewed in terms of

its remedial purposes, can resolve this conflict.

The phrase "any project" in Section 502 empha

sizes the sweep of applicability of the relocation pro

visions. In the 1962 highway relocation amendment,

Congress argiiably gave the Department a choice. The

Department was obliged to require the assurances called

for by that weaker amendment prior to its approval of

"any project. . . for right-of-way acquisition or actual

-48-