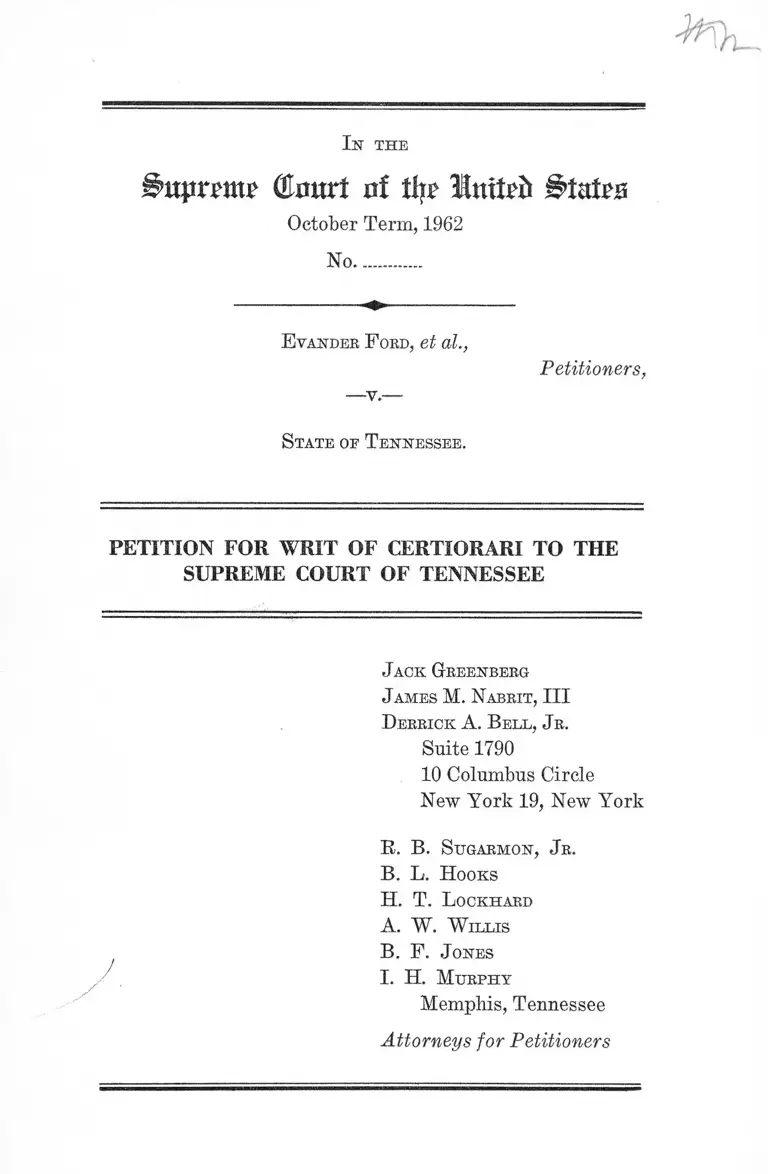

Ford v. Tennessee Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Tennessee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. Tennessee Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Tennessee, 1962. 21d29d27-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96e3a8e9-04ad-4889-9f6e-ab6427677212/ford-v-tennessee-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-tennessee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(Enurt of % Imtpft States

October Term, 1962

No............

E vander F ord, et al.,

—v.—

State oe T ennessee.

Petitioners,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, I I I

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

Suite 1790

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R. B. S itgarmon, J r.

B. L. H ooks

H. T. L ockhard

A. W. W illis

B. F . J ones

I. H. Murphy

Memphis, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinions Below ........................................... 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 1

Questions Presented............................. ............ .............. 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved........ 2

Statement ........................................................................ 3

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided 6

Reasons for Granting the Writ .................................... 9

I—The Judgment of the Court Below Conflicts

With the Principles Established by This

Court That It Is a Denial of Due Process to

Convict Persons of Crimes Without Evidence

of Their Guilt....................................... .......... 9

II—The Conviction of Petitioners Denied Their

Rights of Freedom From State Enforced Ra

cial Segregation Protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United

S tates................................................................. 12

III—If This Court Should Determine That the

Court Below Improperly Decided the Consti

tutional Issues, Justice Requires That an

Order Be Entered Vacating the Judgment

Against Petitioner Katie Jean Robertson .... 13

Conclusion 15

11

T able oe Cases

page

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ................................ 13

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 294 .................. 12

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715 12

Garner v. Louisville, 368 U. S. 157................................9,11

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S, 903 .................................... 12

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 ................................ 12

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association, 202 F.

2d 275 (6th Cir. 1953), judgment vacated and re

manded 347 U. S. 971 (1954) .................................... 12

Patterson v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 600 ............................ 2,14

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ................................... 13

Taylor v. Louisiana, 7 L. ed. 2d 395............................... 9,11

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199..............9,11

Turner v. Memphis, 369 IJ. S. 350 ............................. . 12

Statutes

Tennessee Code Annotated §39-1204 ..................... 2

28 U. S. C. §1257(3).................................................. 1

I s THE

#uprm* (to rt ni % MnxUb States

October Term, 1962

No............

E vander F ord, et al.,

—v.

State oe T ennessee.

Petitioners,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Tennessee entered

in the above entitled case on March 7, 1962, rehearing of

which was denied on May 4, 1962.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Tennessee is re

ported in 355 S. W. 2d 102 (1962), rehearing denied 356

S. W. 2d 726 (1962), and is set forth in the Appendix here

to, infra, pp. 17-23.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Tennessee was

entered March 7, 1962, infra, pp. 24-27. Petition for rehear

ing was denied by the Supreme Court of Tennessee on May

4,1962, infra, p. 28.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, U. S. C. 1257(3), petitioners having asserted below

2

and asserting here deprivation of rights, privileges and

immunities secured by the Constitution of the Tjnited States.

Questions Presented

Whether petitioners were denied their rights under the

due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States:

1. When convictions of willfully disturbing a religious

assembly were based on a record containing no evidence of

their guilt.

2. When convicted of disturbing a religious assembly

for merely peacefully taking seats on a non-segregated

basis at a church youth rally held at a city-owned audi

torium opened to the public.

3. Whether, if this Court should determine that the court

below improperly decided the federal constitutional ques

tions stated above, the doctrine of Patterson v. Alabama,

294 U. S. 600, requires that an order be entered vacating

the judgment against petitioner Katie Jean Robertson.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States.

2. The Tennessee statutory provision involved is §39-

1204, Tennessee Code Annotated, which provides:

If any person willfully disturb or disquiet any as

semblage of persons met for religious worship, or for

educational or literary purposes, or as a lodge or for

the purpose of engaging in or promoting the cause

of temperance, by noise, profane discourse, rude or

3

indecent behavior, or any other act, at or near the

place of meeting, he shall be fined not less than twenty

dollars ($20.00) nor more than two hundred dollars

($200), and may also be imprisoned not exceeding

six (6) months in the county jail.

Statement

On August 30, 1960 (E. 71), the Assembly of God Church

in Memphis, Tennessee (R. 69) held a city-wide Youth

Rally at Overton Park Shell (R. 70) an open air auditorium

located in a publicly owned park (R. 125). The church

group had leased the auditorium from the City of Memphis

(R. 71, 122) and had published advertisements of the ser

vices which were to consist of singing, devotions and a

special film (R. 78-79). Negroes were not excluded from

the public invitation because, according to a church official,

there are no Negro members in the Assembly of God

Church and none were expected to attend (R. 78, 82, 276).

The services began at 7 :30 P.M. with from 400 to 700

people present (R. 72).

About 15 minutes after the service began (R. 73), and

while the group was singing hymns (R. 75), a group of 13

or 14 Negroes including the petitioners (R, 76) entered

and was greeted by the head usher for the group who

testified: “I asked them out of courtesy if he would not

remain, since this was a segregated meeting, featuring the

young people of the Assembly of God” (R. 91). When

the Negroes failed to leave, the usher noting that there

were some 20 rows vacant behind the audience (R. 92),

“got a plan” (R. 92), and suggested that they sit at the

rear of the building since the services were already in

progress (R. 285, 293). At this request, petitioner Ford

replied, “No, we are certainly not going to do that, . . . ”

4

(R. 308), and according to the usher directed the group to

“scatter out” (R. 91).

The Negroes proceeded down into the audience, and

seated themselves in couples among the gathering (R. 92).

They were quiet, properly dressed (R. 80), and made no

noise while talcing seats (R. 277, 293). Nevertheless, ac

cording to State witnesses, as the Negroes moved in, white

people began to move, and some left (R. 93, 288) because

a church official reported “they were not accustomed to

attending services with Negroes” (R. 79-80). This moving

and shifting created some disturbance (R. 276-296).

At this point, the minister in charge of the group, Rev.

Scruggs, testified that the service continued, but that he

called the police and also sent word to assistants that

the film which was scheduled to start should be held up

until the disturbance could be quieted (R. 268). Neverthe

less, when the police arrived about five or ten minutes

later (R. 268, 297), most of the white people had settled

down (R. 298), an offering may have been received (R. 83),

the lights had been lowered (R. 298), and the movie was

in progress (R. 114, 310).

When the police arrived, the lights were turned on again

and the movie was stopped so that the police could find

the petitioners (R. 298). The police were instructed to

locate colored people in the Shell, inform them they were

under arrest and bring them outside (R. 109, 329). Police

officers testified that fourteen Negroes, male and female

were arrested (R. 109). All were seated quietly when the

police arrived, were properly dressed, used no loud or

profane language, engaged in no boisterous or indecent

conduct, and offered no resistance to arrest (R. 112, 326).

Rev. Scruggs contended that he arrested petitioners not

because they were Negroes, but because they created a

5

disturbance when they refused to take seats in the rear

and “decided to slide in and take seats and intermingle

with the crowd” (R. 86, 296). He admitted that “the thing

that caused the disturbance was that they intermingled”

(R. 86), and surmised that the disturbance grew out of

the fact that the white people were not accustomed to

attending services with Negroes (R. 79-80).

“Q. And this disturbed the gathering, in this sense

of the word because they were Negroes? A. I sup

pose that’s true; yes” (R. 80).

Additional indications that it was petitioners’ color and

not their actions that created the disturbance is seen in the

testimony of the head usher who indicated that all white

latecomers (10 to 20 persons) had taken seats among the

audience without incident (R. 291).

“Q. Did any of them enter into a row of seats where

anybody else was sitting, where they would have to

pass over anyone? A. Most of them, we directed

them how to be seated behind others or to where there

were seats vacant on the aisle.

Q. Did any of the persons who came in after the

services began go into a row of seats where it was

necessary for them to pass by another person who

was seated? A. I imagine so. That has been a year

and a half. I am sure that there were some that did

that. I did not pay exactly that close attention as to

where they were sitting. I am sure that there was

some who did that.

Q. Now, did they create any disturbance? A. No,

sir.

Q. It did not. In fact, you hardly noticed it, is that

correct? A. That’s right” (R. 291-292).

6

Following their arrest, the petitioners were tried and

convicted of violating Section 39-1204, Tennessee Code

Annotated.

The petitioners, with the exception of Katie Jean Robert

son, were tried on June 19th and 20th, 1961, and were

sentenced to serve 60 days in the Shelby County Penal

Farm, and fined $200. Petitioner Katie Jean Robertson

was tried on September 25, 1961 and was sentenced to

serve 60 days and fined $175.00.

The Supreme Court of Tennessee affirmed the convic

tions finding that the actions of the defendants created a

disturbance in the religious service and therefore violated

the statute. Moreover, they found that such actions were

willful and designed to created an incident. The Court

stated that the issue of whether Negroes could be segregated

at the service held in a public facility was not present in

this case and the convictions did not violate any constitu

tional rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to

the petitioners.

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

The petitioners were tried before the criminal court of

Shelby County, Tennessee in two separate trials on June

19th and 20th, 1961 and September 25, 1961 (R. 258).

At the conclusion of the testimony in the trial of June

19th, petitioners Evander Ford, Jr., Alford O. Gross, James

Harrison Smith, Ernestine Hill, Johnnie May Rogers,

Charles Edward Patterson and Edgar Lee James, made a

motion to dismiss the charges, maintaining therein that the

arrests followed petitioners’ peaceful efforts to attend a

public meeting in a publicly owned facility leased to a

private group who sought to operate it on a racially segre

gated basis, and therefore such arrest deprived petitioners

7

of their rights under the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 131-136). This

motion was denied (R. 137).

Petitioners were convicted and filed a motion for new

trial on August 7, 1961 (R. 229), relying inter alia on a

denial of their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment to

be admitted on a nonsegregated basis to publicly owned

facilities leased by private lessees for functions to which

the public is invited. The motion was denied on August

15,1961 (E. 231).

In the second trial, in which judgment of conviction was

returned on September 25, 1961, against petitioner Katie

Jean Robertson (R. 251), a motion for new trial raising

federal issues similar to those contained in the motion

filed in the first trial, was overruled on November 3, 1961

(R. 254).

The Supreme Court of Tennessee consolidated the appeal

of Evander Ford, Jr., et al., with that of Katie Jean Robert

son (R. 359). In their Assignment of Error filed with the

Supreme Court of Tennessee on January 15, 1962 (R. 360),

petitioners contended:

1. ‘‘Plaintiffs in Error contention is that the record con

tains no evidence to support a finding that the defen

dants disturbed a religious assembly in violation of

Section 39-1204 of the Tennessee Code Annotated,

and that a conviction of such violation violates the

defendants’ rights to due process of the law guaran

teed to them by the Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution of the United States. (Thompson v.

City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 99; Garner v. Louisiana,

26, 27, 28 Oct. Term 1961, Supreme Court, U. S. A.)”

(R. 366).

8

2. “The Jury and the Court failed to consider the fact

that the defendants were members of the public,

peacefully assembled and worshiping God at public

meeting held at a publicly owned facility namely the

Shell in Overton Park, and that they were peace

fully worshiping and using said public facility in

the same manner as white persons similarly situated;

and that they were arrested, indicted and convicted

solely because of the color of their skin” (R, 366).

The Supreme Court of Tennessee ruled that the appeal

of Katie Jean Robertson must be affirmed for failure to

timely file the Bill of Exceptions and that no reversible

error was found in the technical record before the Court

(R. 393-2).

As to the appeals of Evander Ford, Jr., et al., the Su

preme Court of Tennessee construed petitioners’ acts as

violative of Section 39-1204, Tennessee Code Annotated,

in that they refused to be seated where requested and

dispersed themselves throughout the Audience, which ac

tions the court below concluded were planned and “com

pletely interrupted the service.”

The court below then summarized petitioners’ constitu

tional objections as follows:

The Defendants next argue that their constitutional

rights are being violated by this conviction because

this is a publicly owned facility and they could not

be excluded. First, it must be noted that the Defen

dants were tendered seats at this meeting even though

they had been denied admission at the outset. Second,

this is not a suit to enjoin a discriminatory practice,

nor is it a damage suit based upon the violation of

civil rights, but rather a criminal action charging the

Defendants with willfully disturbing a religious as

9

sembly. Whether these Defendants had a right to be

at the place where this religions meeting was being

conducted is not an issue in this lawsuit. The sole

issue here is whether or not these Defendants willfully

disturbed the meeting that was being held there and

we have hereinbefore determined this question ad

versely to the Defendants’ contention.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I

The Judgment of the Court Below Conflicts With the

Principles Established by This Court That It Is a Denial

of Due Process to Convict Persons of Crimes Without

Evidence of Their Guilt.

The principle that the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

forbids criminal convictions based upon no evidence of

guilt was set forth by this Court in Thompson v. City of

Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, and has been applied and reaffirmed

in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, and Taylor v. Loui

siana, 7 L. ed. 2d 395. This record presents another occa

sion for the application of this principle.

The petitioners were convicted under a State statute pro

hibiting willful disturbance of a religious assembly “by

noise, profane discourse, rude or indecent behavior, or any

other act.” There was no claim or evidence that petitioners

engaged in any noise, profane discourse or rude or in

decent behavior. The indictment charging them alleged

that they disturbed and disquieted an assemblage of per

sons met for religious worship in that “after being refused

admittance to the services therein, did force their way into

the said assemblage, seat themselves among the worshipers

10

and by this act did cause the disruption of said religious

assemblage.” However, the record shows that petitioners

entered the open air auditorium owned by the City of Mem

phis and leased to a religious group and merely peacefully

took seats therein during the services. When they first

entered an usher told them that the meeting was racially

segregated and asked them to leave but, subsequently of

fered them seats at the rear of the auditorium some twenty

rows behind the audience. Petitioners declined this offer

and proceeded down into the auditorium where they quietly

seated themselves among the audience. In this regard, there

is no evidence that petitioners conducted themselves any

differently from ten to twenty white persons who, according

to testimony of the ushers, also entered after the services

had started. The evidence is clear that if there was any

disturbance of the meeting it was caused by white persons

in the audience who began to change their seats after the

Negroes entered because “they were not accustomed to

attending services with Negroes” (E. 78-80).

The services which were in progress continued and were

not halted until the police, having been summoned by the

minister in charge of the meeting, arrived at the audi

torium and halted the proceedings in order to locate and

arrest all Negro persons in the audience. The police re

ported that the Negroes were properly dressed, used no

rude or profane language, were engaging in no boisterous

or indecent conduct and offered no resistance to arrest.

It is apparent that the disturbance of the service resulted,

as the minister in charge indicated, from the fact that the

petitioners “intermingled” with whites instead of segregat

ing themselves to the rear of the gathering as directed.

Thus, it is also apparent that the arrest of the petitioners

was based upon their color and the fact that they failed to

racially segregate themselves when taking seats in the audi

11

ence. As this Court held in Garner v. Louisiana, supra, the

mere refusal to obey a segregation custom cannot by itself

be made the equivalent of a breach of the peace. It should

be noted that petitioners had a plain legal right to be present

in the auditorium and not to be racially segregated therein

because the premises were owned and operated by the City

of Memphis for the use of the public, as is argued below

in Part II of this Petition.

There is no evidence to support the conclusion reached

by the court below that petitioners attended the services

for the purpose of intentionally causing a disturbance.

Indeed, there is every indication that any Negro attempting

to attend the services on a nonsegregated basis, regardless

of his intentions, would have caused a similar upset among

those white persons present who were not accustomed to

worshipping with Negroes. Clearly, it was the petitioners’

color and not either their actions or intentions that led

to the disturbance and their arrests. The court below denies

that race was a factor in the arrests. There remains then

no basis on which to sustain the convictions, and the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires that

they be reversed. Thompson v. City of Louisville, supra;

Garner v. Louisiana, supra and Taylor v. Louisiana, supra.

12

II

The Conviction of Petitioners Denied Their Rights

of Freedom from State Enforced Racial Segregation

Protected by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

Petitioners’ convictions were obtained in violation of

their Constitutional rights in that they resulted directly

from efforts by petitioners to attend, on a nonsegregated

basis, a religions youth rally held at a city-owned audito

rium open to, and provided for, the use of the public. If

the convictions were not based upon no evidence of guilt,

as is argued above, the only possible conclusion available

on the record is that the state court equated petitioners’

breach of the segregation custom or policy with a distur

bance of the assembly, and is merely enforcing racial segre

gation under another label. This the State cannot do under

the numerous decisions of this Court. Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 294; Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903;

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879.

The leasing of this open-air auditorium to a private

group does not alter the conclusion that the State is for

bidden to enforce segregation. This Court has repeatedly

held that the enforcement of racial segregation in publicly-

owned facilities cannot legally be accomplished by leasing

such facilities to private persons. Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715; Turner v. City of Mem

phis, 369 U. S. 350; Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical

Association, 202 F. 2d 275 (6th Cir. 1953), judgment vacated

and remanded, 347 U. S. 971.

The State cannot enforce segregation in such facilities

indirectly through the use of its criminal laws any more

than it could do so directly by a segregation law or rule.

The Constitution forbids the courts, as well as other arms

13

of the States, from enforcing racial discriminations. Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249.

The Supreme Court of Tennessee stated in its opinion

that the issue in the case was not whether petitioners had

a right to be at the meeting, but rather whether they will

fully disturbed the meeting. However, the record plainly

indicates that the only claim that petitioners created a

disturbance was based upon the fact that their mere pres

ence as Negroes in a white assembly was in itself a dis

turbance. Thus the State has made the presence of Negroes

in a white assembly a crime just as surely as if it had

directly punished petitioners under a segregation law. It

is submitted that the issues presented by this case deserve

plenary consideration by this Court because the decision

of the court below ignores the principle that States and

other agents may not enforce racial segregation.

Ill

If This Court Should Determine That the Court Below

Improperly Decided the Constitutional Issues, Justice

Requires That an Order Be Entered Vacating the Judg

ment Against Petitioner Katie Jean Robertson.

The petitioner Katie Jean Robertson was indicted in

the same indictment with the other petitioners based upon

the same occurrences. The record reveals that her conduct

was no different from that of the other petitioners. How

ever, because she was unavailable for trial when the other

petitioners were tried, her trial was separate. The same

issues were raised and presented to the trial court in

her case and her case was consolidated with that of the

others on appeal. The cases were decided by the court be

low in one opinion and the record of both trials has been

certified to this Court as one record. The court below ruled

14

that it could not consider the merits of the constitutional

arguments urged for petitioner Katie Jean Robertson

(which were identical to those urged by the other peti

tioners) on the ground that the Bill of Exceptions for

her case was filed in the Supreme Court of Tennessee two

days too late. The court thus determined that it must

affirm the conviction of petitioner Robertson as noted.

In the same opinion the court rejected all of the arguments

urged on behalf of the other petitioners, which were the

same arguments made on behalf of petitioner Robertson.

It is submitted that in accordance with the principles

of Patterson v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 600, if this Court should

determine that the court below improperly decided the

federal constitutional questions presented, this Court should

enter an order vacating the judgment as to petitioner

Robertson in view of that supervening development. It is

submitted that the ends of justice would then require that

the Court vacate the judgment and remand it to the Su

preme Court of Tennessee in order that that court might

reconsider its disposition of the case of Katie Jean Robert

son in light of the properly applicable constitutional prin

ciples. The rule stated in Patterson v. Alabama, 294 U. S.

600, 617, in circumstances very similar to this, was that:

We have frequently held that in the exercise of our

appellate jurisdiction we have power not only to cor

rect error in the judgment under review but to make

such disposition of the case as justice requires. Anri

in determining what justice does require, the Court is

bound to consider any change, either in fact or in law,

which has supervened since the judgment was entered.

We may recognize such a change, which may affect the

result, by setting aside the judgment and remanding

the case so that the state court may be free to act.

15

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons, it is respect

fully submitted that the petition for a writ of certiorari

should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greekberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Derrick A. B ell, J r.

Suite 1790

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R. B. Sugarmoh, J r.

B. L. H ooks

H. T. L ockhard

A. W. W illis

B. F. J okes

I. H. Murphy

Memphis, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

Opinion of Supreme Court

of Tennessee

OPINION

The Defendants, Evander Ford, Jr., Alfred O’Neil Gross,

James Harrington Smith, Ernestine Hill, Johnnie Mae

Rogers, Charles Edward Patterson, and Edgar Lee James,

were convicted upon the same trial for willfully disturbing

an assemblage of persons meeting for religious purposes

(Section 39-1204, Tennessee Code Annotated), and each was

sentenced to serve sixty days in the Shelby County Penal

Farm, plus a fine of $200.00.

The Defendant, Katie Jean Robertson, was tried sepa

rately, she not being available at the time of the first trial,

and was convicted of the same offense and sentenced to

serve sixty days and fined $175.00. Since these two cases

grew out of the same set of facts and the Defendants were

acting in concert with each other, the cases were joined

for purposes of appeal.

In the case of the Defendant, Katie Jean Robertson, the

conviction must be affirmed for failure to timely file the

bill of exceptions. The Trial Court overruled the Defen

dant’s motion for a new trial on November 3, 1961. On

Friday, December 1, 1961, the Defendant moved the Court

for additional time in which to file and prepare her bill of

exceptions. This motion was granted by the Trial Judge

and the time for filing was extended thirty days from the

3rd day of December, 1961. As a result of this extension

the Defendant had until January 2,1962 in which to prepare

and file the bill of exceptions. However, the bill of excep

tions was not filed until January 4, 1962, which is two days

late. A bill of exceptions which is filed too late does not

become a part of the record in a case and cannot be looked

18

to for any purpose. O’Brien v. State, 193 Tenn. 361. This

leaves only the technical record before the Court and we

are unable to detect any reversible error therein.

Having disposed of Katie Jean Robertson’s case the

Court will now proceed to discuss the appeal as to the re

maining Defendants. At the outset it must be noted that

all of the proof in the record is uncontroverted. These De

fendants are negro youths and their criminal prosecution

resulted from an incident which took place in the City of

Memphis on the evening of August 30,1960. It appears that

the Assembly of God Church on this evening had leased

the “Shell”, a municipally owned amphitheater situated in

Overton Park of that city, for the purpose of conducting

a youth rally as a part of their church activities. This

meeting had received a considerable amount of advertise

ment as to time and place it was to be conducted.

The meeting commenced at 7:30 o’clock, P.M. on this

evening. At approximately 7:45 o’clock, P.M. the Defen

dants herein, and some other negro youths who are not on

trial here, entered the amphitheater. An usher on duty at

this entrance met these Defendants as they entered. The

usher then informed the group that it would be better if

they did not come in, that this was a meeting for the youth

of the Assembly of God Church. When the Defendants

would not leave the usher asked them to take the rear seats.

At this time the Defendant, Evander Ford, Jr., who was

the apparent leader of this group, turned and told his

group to “scatter out”. The Defendants then broke into

groups of two and simultaneously disbursed themselves

throughout the audience. Even though there were seats

available at the ends of the rows, the Defendants for the

most part proceeded to step over the people already seated

and moved to the center of the rows. The people who were

already seated began to move away and in some instances

19

left the meeting. As a result of this mass entrance a gen

eral milling around was caused and an undercurrent went

up throughout the audience which caused a delay in the

service that was in progress. The police were then sum

moned and the Defendants were placed under arrest for

the offense indicated above.

The Defendants stand convicted of Section 39-1204, Ten

nessee Code Annotated, which reads as follows:

“If any person willfully disturb or disquiet any assem

blage of persons met for religious worship, or for

educational or literary purposes, or as a lodge or for

the purpose of engaging in or promoting the cause of

temperance, by noise, profane discourse, rude or in

decent behavior, or any other act, at or near the place

of meeting, he shall be fined not less than twenty dol

lars ($20.00) nor more than two hundred dollars ($200),

and may also be imprisoned not exceeding six (6)

months in the county jail.”

The Defendants first argue that the statute only con

demns acts which are noisy, rude, profane, indecent, or

other similar acts and that their action was none of these,

therefore, the State has failed to make out a case against

them. The State on the other hand insists that the statute

reaches any willful disturbance of a religious assembly

regardless of how it is accomplished. This squarely presents

us with the problem of the construction of this statute.

At the outset it must be noted that this statute is not a

breach of the peace statute as such, but rather it is a statute

which is designed to protect to the citizens of this State the

right to worship their God according to the dictates of their

conscience without interruption. As a general rule these

statutes have been very liberally construed by the Court.

Hollingsworth v. State, 37 Tenn. 518. However, in order to

20

determine the exact boundaries of this statute we feel that

it is necessary to review its historical development.

The first statute upon this subject made any person who

would disturb a religious assembly punishable as a rioter

at common law. Chapter 35 of the Acts of 1801. Then by

Chapter GO of the Acts of 1815, the legislature enacted an

additional statute to supplement Chapter 35 of the Acts of

1801. The part of Chapter 60 of the Acts of 1815 which is

pertinent to our discussion here reads as follows:

“It shall be the duty of all justices of the peace, . . . that

whenever any wicked or disorderly person or persons

shall either by word or gesture or in any other manner

whatsoever disturb any congregation which may have

assembled themselves for the purpose of worshipping

Almighty God, . . . shall immediately cause offender or

offenders to be apprehended and brought before them

or some other justice of the peace for the county in

which such offense may be committed . . . ” (Section 1,

Chapter 60, Acts of 1815) (Emphasis supplied).

Then in 1858 the first Code of this State was adopted

which contained a section that is the same as Section 39-

1204, Tennessee Code Annotated, except that it only cov

ered religious assemblies. By Chapter 85 of the Acts of

1870 this section was extended to cover educational and

literary meetings and by Chapter 209 of the Acts of 1879

the section was placed in its present form.

However, when the Code of 1858 was adopted, Chapter

35 of the Acts of 1801 and Chapter 60 of the Acts of 1815

were brought forward into that Code. Thus, the Code of

1858 contained both Chapter 35 of the Acts of 1801 and

Chapter 60 of the Acts of 1815, along with a section which

was the same as our present Section 39-1204 after the

abovementioned amendments. This remained in this state

21

of affair until 1921 when the Court was called upon to

compare these various sections in Dagley v. State, 144

Tenn. 501. The Court in this case reached the conclusion

that the section which is now Section 39-1204, of our

present Code, embraced the same offense which was set

out in the section containing Chapter 35 of the Acts of

1801 and Chapter 60 of the Acts of 1815.

It will be noted from the quoted part of Chapter 60

of the Acts of 1815 that it constituted an offense to disturb

a religious assembly in any manner whatsoever. There

fore, in the light of the conclusion reached by the Court

in the Dagley case, supra, i.e., the offense set out in Chap

ter 60 of the Acts of 1815 was included in the offense

prescribed in what is now Section 39-1204, Tennessee Code

Annotated, the only logical result to be reached here is

that the phrase “or any other act” which appears in Sec

tion 39-1204, Tennessee Code Annotated, is all encompass

ing and it is unlawful for anyone to willfully disturb a

religious assembly in any manner whatsoever.

In view of the construction which must be placed upon

Section 39-1204, Tennessee Code Annotated, we are of the

opinion that these Defendants violated the statute. Un

questionably the act was willful. These Defendants had

been tendered seats at this meeting even though they were

at first asked not to come in. However, the Defendants

would not take these seats and upon command of their

leader to “scatter out” they disbursed themselves through

out the audience simultaneously. The proof shows that

there were seats available at the ends of the rows where

they could be seated, but they, nevertheless, proceeded

to step over the people already seated in an effort to get

to the center of the rows. These acts are wholly incon

sistent with any theory that these Defendants came with

the intent of joining in the meeting. The very precise

manner in which this maneuver was executed indicates

22

very clearly that these Defendants had planned their

course of action before arriving at the meeting. This

leaves us no choice but to conclude that this was a well

organized scheme designed to create an incident.

This brings us to the question of whether or not their

act disturbed the meeting. The record shows that when

the Defendants descended upon this meeting in mass and

began to step over the persons already seated it caused

these people , to move to let them in and some to move

away, and others to leave the meeting*. Reverend Scruggs,

the official in charge of the meeting, stated that there was

quite a commotion caused by this act with all these people

moving around and further that they had to delay the

service. The Court in the case of Holt v. State, 60 Tenn.

192, ruled that it was only necessary that the act attract

the attention of any part or parts of the assembly to

constitute a violation of the statute. This act undoubtedly

attracted the attention of a great portion of this assembly

if not all of it, but the Defendants’ act even went further

than that which is required under the rule in the Holt case,

supra, because their act completely interrupted the ser

vice. We are, therefore, of the opinion that there is more

than ample proof contained in this record to support the

verdict of the jury.

The Defendants next argue that their constitutional

rights are being violated by this conviction because this

is a publicly owned facility and they could not be excluded.

First, it must be noted that the Defendants were tendered

seats at this meeting even though they had been denied

admission at the outset. Second, this is not a suit to

enjoin a discriminatory practice, nor is it a damage suit

based upon the violation of civil rights, but rather a crim

inal action charging the Defendants with willfully disturb

ing a religious assembly. Whether these Defendants had

a right to be at the place where this religious meeting was

23

being conducted is not an issue in this lawsuit. The sole

issue here is whether or not these Defendants willfully

disturbed the meeting that was being held there and we

have hereinbefore determined this question adversely to

the Defendants’ contention.

Lastly, the Defendants contend that the verdict of the

jury is so severe that it evinces passion, prejudice and

caprice and, therefore, is void. The evidence as presented

by the record clearly shows them to be guilty of violating

this particular statute. We have diligently searched this

record and are unable to find any mitigating circumstances

which would warrant us in disturbing the verdict of the

jury.

Judgment affirmed.

P rewitt, C.J.

24

Oi’der of Supreme Court

of Tennessee

No. 37462

E vander F ord, J r., et al.,

-v-

State of T ennessee.

Shelby Criminal.

Affirmed.

Came the plaintiffs in error by counsel, and also came

the Attorney General on behalf of the State, and this

cause was heard on the transcript of the record from the

Criminal Court of Shelby County; and upon consideration

thereof, this Court is of opinion that there is no reversible

error on the record, and that the judgment of the Court

below should he affirmed, and it is accordingly so ordered

and adjudged by the Court.

It is therefore ordered and adjudged by the Court that

the State of Tennessee recover of Evander Ford, J r . ;

Alfred O’Neil Gross; James Harrington Smith; Ernestine

Hill; Johnnie May Rogers; Charles Edward Patterson;

and Edgar Lee James; the plaintiffs in error, for the use

of the County of Shelby, the sum of $200.00 each, the fine

assessed against Evander Ford, Jr. et al. in the Court

below, together with the costs of the cause accrued in this

Court and in the Court below, and execution may issue

from this Court for the cost of the appeal.

It is further ordered by the Court that the plaintiffs

in error be confined in the county jail or workhouse of

25

Shelby Comity, subject to the lawful rules and regulations

thereof, for a term of sixty days each, and that after

expiration of the aforesaid term of imprisonment, they

remain in the custody of the Sheriff of Shelby County until

said fine and costs are paid, secured or worked out as re

quired by law, and this cause is remanded to the Criminal

Court of Shelby County for the execution of this judgment.

The Clerk of this Court will issue duly certified copies

of this judgment to the Sheriff and the Workhouse Com

missioner of Shelby County to the end that this judgment

may be executed.

3/7/62

26

Order of Supreme Court

of Tennessee

K atie J ean R obertson,

—v.—

State op Tennessee.

Shelby Criminal.

Affirmed.

Came the plaintiff in error by counsel, and also came

the Attorney General on behalf of the State, and this

cause was heard on the transcript of the record from the

Criminal Court of Shelby County; and upon consideration

thereof, this Court is of opinion that there is no reversible

error on the record, and that the judgment of the Court

below should be affirmed, and it is accordingly so ordered

and adjudged by the Court.

It is therefore ordered and adjudged by the Court that

the State of Tennessee recover of Katie Jean Robertson,

the plaintiff in error, for the use of the County of Shelby,

the sum of $175.00, the fine assessed against Katie Jean

Robertson in the Court below, together with the costs of

the cause accrued in this Court and in the Court below,

and execution may issue from this Court for the cost of

the appeal.

It is further ordered by the Court that the plaintiff

in error be confined in the county jail or workhouse of

Shelby County, subject to the lawful rules and regulations

thereof, for a term of sixty days, and that after expiration

of the aforesaid term of imprisonment, she remain in the

27

custody of the Sheriff of Shelby County until said fine

and costs are paid, secured or worked out as required by

law, and this cause is remanded to the Criminal Court of

Shelby County for the execution of this judgment.

The Clerk of this Court will issue duly certified copies

of this judgment to the Sheriff and the Workhouse Com

missioner of Shelby County to the end that this judgment

may be executed.

3/7/62

28

Order Denying Rehearing

K atie J ean R obertson, E vander F ord, J r., et al.,

State of T ennessee.

Shelby Criminal.

Petition to Rehear Denied.

This cause coming on further to he heard on a petition

to rehear and reply thereto, upon consideration of all which

and the Court finding no merit in the petition, it is denied

at the cost of the petitioner.

5/4/62

'