Hall v. Holder Reply Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 27, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hall v. Holder Reply Brief of Appellants, 1991. 324f9221-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/973fcf93-9677-46ef-9cbf-07dd4d2d64cc/hall-v-holder-reply-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

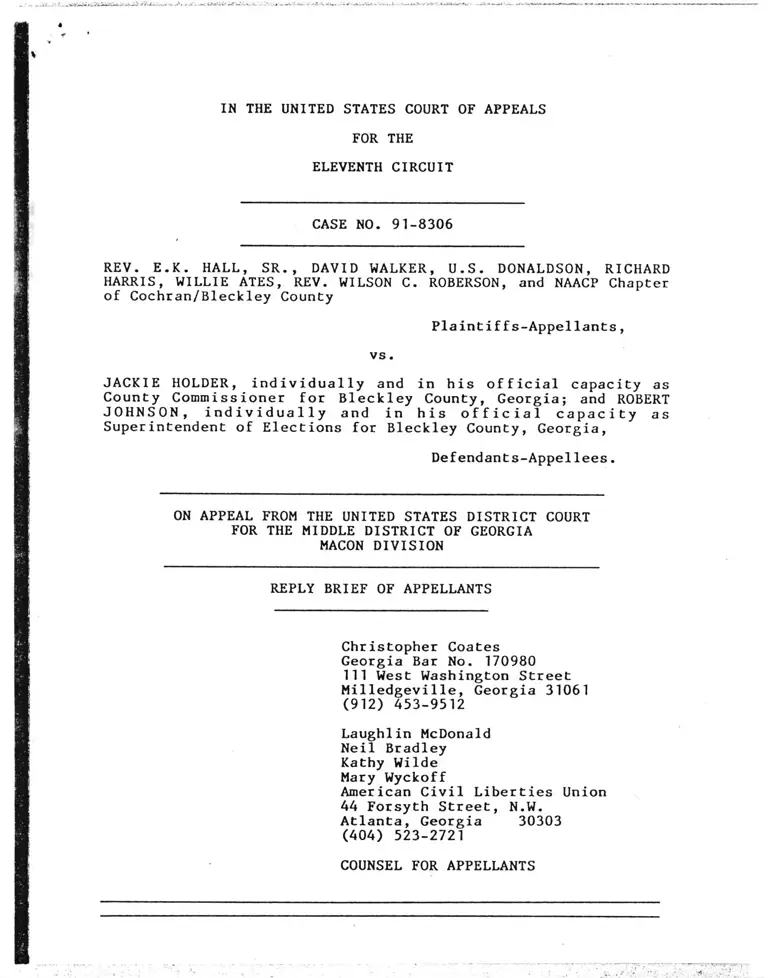

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE

ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

CASE NO. 91-8306

REV. E.K. HALL, SR., DAVID WALKER, U.S. DONALDSON, RICHARD

HARRIS, WILLIE ATES, REV. WILSON C. ROBERSON, and NAACP Chapter

of Cochran/Bleckley County

vs.

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

JACKIE HOLDER, individually and in his official capacity as

County Commissioner for Bleckley County, Georgia; and ROBERT

JOHNSON, individually and in his official capacity as

Superintendent of Elections for Bleckley County, Georgia,

Defendants-Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

MACON DIVISION

REPLY BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Christopher Coates

Georgia Bar No. 170980

111 West Washington Street

Milledgeville, Georgia 31061

(912) 453-9512

Laughlin McDonald

Neil Bradley

Kathy Wilde

Mary Wyckoff

American Civil Liberties Union

44 Forsyth Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 523-2721

COUNSEL FOR APPELLANTS

t ab le of c o n t e n t s

TABLE OF CONTENTS....................................... 1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................... 11

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES................................. 1

ARGUMENT AND CITATIONS OF AUTHORITY.................... 3

CONCLUSION.............................................. 25

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Avery v . Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953)................. 6

Anderson v . Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964)............... 6

Bell v^ Southwell, 376 F.2d 659 (5th Cir. 1967) ..... 6

Campos v. City of Baytownj Texas, 840 F.2d 1240 (5th

Cir. 1988) ......................................... 13> 24

'^Carrollton Branch NAACP v. Stallings, 829 F . 2d 1547

(11th Cir. 1987) . ................................ 9, 10, 14

Citizens for a Better Gretna v . City of Gretna, 636

F.Supp 1113 (E.D.La. 1986) . ........................ 13, 14

Gingles v . Edmisten, 590 F.Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C. 1984).. 18

Harris v. S iegelman, 695 F.Supp. 517 (M.D. Ala.

1988) ................................................ 7 > 8

Harris v. Graddic_k, 593 F. Supp. 128 (M.D. Ala.

1984) ................................................ 7 > 8

Jackson v. Edge field County, South Carolina School

District,~~650 F. Supp. 1176 (D.S .C. 1986)............. 18

Lodge v . Buxton, 639 F.2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1981) ..... 18

Lucas v. Townsend, 908 F .2d 851 (11th Cir. 1990).... 7

NAACP of Cochran/Bleckley County v . Bleckley County,

Civ. No. 88-32-MAC (M. D . Ga . ) . . . ........................ 5

Over ton v . Austin, 871 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1989)...... 10

*Rodger s v . Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)....... 18, 21, 22

*Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) ...............

........ 7.77.. 6, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20

^United States v. Marengo County Commission, 731 F.2d_

1546 (1 1th Cir. 1984) . 777......................... 5, 7, 8

ii

Wh i tus v . Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967)................ °

Upqtweeo Citizens for Better Government Westwego, 906

F . 2d 1042 (5th Cir . 1990) . .......................... 17

OTHER AUTHORITIES

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 28-9 (1982).... 5, 24

H.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. 30 (1981)..... 24

Wildgen, "Adding Thornburg to the Thicket: The Ecological

Fallacy and Parameter Control in Vote Dilution Cases,

20 Urban Lawyer 155, 169 (1988).......................... 15

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Whether the district court erred as a matter of law by

refusing to consider evidence other than that drawn from prior

elections, such as socio-economic or other barriers to voting and

political participation, the history of segregation, racial

campaign appeals, and the testimony of experienced local politi

cians, in holding that plaintiffs' failed to prove that voting in

Bleckley County, Georgia was racially polarized?

2. Whether the district court was clearly erroneous in

finding that plaintiffs failed to prove the existence of racially

polarized voting?

3. Whether the district court erred as a matter of law in

holding that plaintiffs failed to prove that the black community

was politically cohesive because election returns did not show "a

pattern of bloc voting" or "a pattern of unified support" for black

candidates, and by failing to consider other evidence of cohesive

ness, such as a distinctive socio-economic status and a history of

segregation and discriminatory treatment of the black community?

4. Whether the district court was clearly erroneous in

holding that plaintiffs failed to prove that the black community

was politically cohesive?

5. Whether the district court erred as a matter of law in

holding that the issue of whether the majority vote requirement for

the Bleckley County Commissioner had a discriminatory purpose or

effect was not properly before the court because (a) the majority

1

vote statute was a part of state law which the county lacked power

to change, and (b) the claim that the majority vote statute

violated the Voting Rights Act was the subject of pending litiga

tion in another district?

6. Whether the district court erred as a matter of law in

holding that plaintiffs failed to produce "any evidence" that the

at-large elected, sole commissioner form of government was adopted

or was being maintained with a racially discriminatory purpose

because they failed to present specific, smoking gun evidence, and

in refusing to consider circumstantial evidence of. racial purpose?

7. Whether the district court was clearly erroneous in

finding that the at-large elected, sole commissioner form of

government was not adopted or being maintained with a racially

discriminatory purpose?

8. Whether the district court erred in concluding that black

voters were not denied the equal opportunity to participate in the

political process and elect candidates of their choice by the at-

large elected, sole commissioner form of government in violation of

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act?

2

ARGUMENT AND CITATIONS OF AUTHORITY

I. Past Discrimination and Its Continuing Effects

The defendants argue that "any alleged past discrimination in

Bleckley County or disparities in education, housing or income does

[sic ] not presently hinder blacks from registering and

participating in Bleckley County politics." Brief of Appellees, p.

9. First, this argument is expressly contrary to the findings of

the district court, findings which the defendants do not contend

are clearly erroneous.

According to the district court, the depressed socio-economic

status of blacks hinders their ability "to participate in the

Bleckley County political process because... less educated people

are more difficult to mobilize to vote even if they are registered

to vote." (R2-59-5) The court further found that socio-economic

barriers to minority participation in the political process "are

today compounded by the fact that Bleckley County now has only one

voting precinct for the entire 219 square-mile area." (R2-59-6

n.3) Given the facts that blacks are poorer than whites and own

fewer automobiles and telephones, and because of the lack of public

transportation, it is much more difficult to organize and mobilize

the black community for effective political activity, including

campaigning, soliciting contributions, and get-out-the-vote drives.

Second, the defendants are incorrect that plaintiffs'

witnesses established "there have been no barriers to

3

blacks... voting in Bleckley County from at least 1964 to the

present." Brief of Appellees, p. 8. To the contrary, registration

was permitted only at the courthouse until 1984, which discouraged

many blacks from registering. (R4-334, 338) In addition,

plaintiff Roberson testified that because voting in the county is

conducted at the Jaycee Barn, a facility owned by an all white

organization, "a lot of people will not go there to vote." (R3-83)

Third, the defendants ignore the fact that black voter turn

out is consistently lower than white voter turn out.^ For

example, at the 1986 referendum election concerning whether the at-

large elected sole commissioner system would be retained, black

participation therein was "a small percentage of participation."

(R4-321) The depressed level- of black voter participation is

further reflected in the 1988 . exit poll conducted by the

plaintiffs. A total of 794 whites (13% of age eligibles and 19% of

registered voters) participated in the exit poll, but only 164

blacks (11% of age eligibles and 17% of registered voters). (P.

Exh. 390) Socio-economic factors continue to have a present day

1 While blacks and whites are registered at approximately the

same rates, the defendants are incorrect that blacks are registered

at a higher rate than whites in Bleckley County. Brief of

Appellees, p. 8. As of 1988, there were 5,327 registered voters in

Bleckley County, 4,303 (81%) white and 1,024 (19%) black.

According to the 1990 Census, there are 7,719 residents of voting

age in the county, 6,245 (81%) white and other, and 1,474 (19%)

black. Thus, 69% of the age eligible white population is

registered, and 69% of the age eligible black population.

4

effect on minority political participation in Bleckley County 2

II. Discrimination in the Appointment Of Election Officials Is

Injury in Fact and Law

The defendants breezily dismiss plaintiffs' evidence of

discrimination in the appointment of poll workers and managers on

the grounds that "[n]o evidence whatsoever was presented that

indicated black citizens have had a problem voting due to the

number of black poll workers and managers or that the number of

black workers and managers is attributable to race discrimination.

Brief of Appellees, p. 14. Plaintiffs do, of course, have a

"problem" with discrimination in the appointment of poll workers

and managers in Bleckley County and are attempting to remedy that

problem now in Federal District Court. See, NAACP of

Cochran/Bleckley County v. Bleckley County, Civ. No. 88-32-MAC

(M.D.Ga.). More to the present point, the failure to appoint

blacks as poll workers and managers is a "problem" as a matter of

fact and law, while plaintiffs are not required under the results

test of Section 2 to prove that a challenged voting practice is

^While the district court found as a matter of fact that there

was a causal connection between the depressed socio-economic status

of blacks and their depressed political participation, where such

disparities are found a causal connection is presumed as a matter

of law. S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 29 n.114 (1982);

United States v. Marengo County Commission, 731 F.2d 1546, 1568-69

(11th Cir. 1984).

5

motivated by a discriminatory purpose. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478

U.S. 30, 50-1 (1986).

The courts have frequently held that some forms of

discrimination are so egregious that they are invalid apart from

any injury they may inflict. Thus, in jury discrimination cases

once a significant statistical racial disparity is shown, the law

requires relief even though the accused is unable to show any

injury in fact. Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, 552 & n.2 (1967).

It is not even necessary to prove actual discrimination if a

racially conscious selection system affords a ready opportunity for

its practice. Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953). In cases

involving the electoral process, the courts have fully applied the

rationale of these decisions.

In Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964), the Court struck

down a Louisiana law requiring the designation of the race of each

candidate on the ballot. In reaching its decision the Court held

that the "vice-lies not in the resulting injury but in the placing

of the power of the State behind a racial classification that

induces racial prejudice at the polls." 375 U.S. at 456. Applying

the reasoning of Anderson, the Fifth Circuit invalidated local

elections in Sumter County, Georgia because they had been held on

a racially segregated basis and without requiring the plaintiffs to

show that the outcome would have been different. According to the

court, "there are certain discriminatory practices which, apart

from demonstrated injury or the inability to do so, so infect the

processes of the law as to be stricken down as invalid. Bell v .

6

Southwell, 376 F.2d 659, 662 (5th Cir. 1967). The exclusionary

practices of Bleckley County in this case are stark and flagrant,

and they induce racial prejudice at the polls and in the elective

process. Plaintiffs are injured by these practices as a matter of

law, and their voting strength as a consequence is diluted.

In addition, Congress expressly provided when it amended

Section 2 in 1982 that whether or not a minority can register and

vote does not end the statutory inquiry. Section 2 can also be

violated "if a protected class has 'less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the political

process.'" United States v. Marengo County Commission, 731 F.2d

1546, 1556 (11th Cir. 1984)(quoting 42 U.S.C. 1973 (b)).

According to the senate report that accompanied the 1982

amendments, "Section 2...also prohibits practices which, while

episodic and not involving permanent structural barriers, result in

the denial of equal access to any phase of the electoral process

for minority group members." S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.

30 (1982). The house report is even more specific and provides

that Section 2 extends to the "refusal to appoint minority

registration and election officials." H.R. Rep. No. 227 , 97th

Cong., 1st Sess. 14 (1981). The courts have, accordingly,

consistently held that the results standard of Section 2 can be

violated by the refusal to appoint minority election officials.

Harris v. Graddick, 593 F.Supp. 128, 133 (M.D.Ala. 1984); Harr is v .

Siegelman, 695 F.Supp. 517, 526 (M.D.Ala. 1988); United States v.

Marengo County Commission, supra, 731 F.2d at 1570; Lucas v.

7

Townsend. 908 F.2d 851, 857 (lUh C i, 1990)C".a 'standard,

practice, or procedure' within the meaning of section 2 can include

the appointment of poll officials ).

The legal injury to black citizens caused by their exclusion

from poll manager and worker positions is not limited to the mere

act of casting a ballot, although the lower turn out rate of blacks

indicates that they are in fact intimidated or deterred from voting

by the county's discriminatory practices, just as they are deterred

from voting at the "all white" Jaycee Barn. The actions of the

county also deny blacks the equal opportunity to serve as election

officials and participate in the electoral process. They

stigmatize blacks by stamping them as inferior and not worthy to

participate in the conduct of elections. They erode the confidence

blacks have in the system's fairness. See, llnited States n

M-reneo County Commission, supra, 731 F.2d at 1570 ("lb]y having

few black poll officials...county officials impaired black access

to the political system and the confidence of blacks in the

system's openness ).

The courts have recognized that discrimination in the

appointment of poll workers and managers has a direct impact

-political socialization." Harris v. Siegelman, su£ra, 695 F.Supp.

at 526. That is, such discrimination fosters an official attitud

that minority voters cannot participate in the electoral process on

the same terms and to the same extent as non-minority voters.

HarriS v. Graddick, supra, 593 F.Supp. at 133. This attitude in

turn has a far reaching impact on political behavior by enhancing

8

polarized

■ r. if/tf jfvi S ^ L ^ * /v 3 » 5 X .i i

racial isolation, exacerbating racially

depressing black political participation.

Blacks in Bleckley County are injured by

exclusion as poll managers and workers. Such

evidence of racial polarization and that the

elections dilutes minority voting strength.

voting and

their discriminatory

exclusion is strong

existing system of'

III. Blacks Are Geographically Compact

The defendants acknowledge, as they must, that Carroll ton

Branch of NAACP v. Stallings, 829 F.2d 1547 (11th Cir. 1987), is

controlling, and that an at-large elected sole commissioner system

of county government can be challenged under the vote dilution

principles of Section 2. Brief of Appellees, pp. 18, 21. In

Carrollton Branch of NAACP, a challenge to the sole commissioner

system in Carroll County, Georgia, the district court rejected the

plaintiffs' evidence of geographic compactness in proposed three

member and five member forms of commission government. The court

of appeals reversed, holding that the exclusion of such evidence

was error. According to the court:

The demographic evidence proffered by plaintiffs is

highly relevant to a showing under Gingles: whether black

voters in Carroll County are sufficiently numerous and

compact to constitute a majority in a single member

district, if single member districts were created out of

the one county district. In this case, it is the at-

large nature of the districting'scheme which is alleged

to operate in the same fashion, as multi-member districts

in diluting black voting strength. Clearly, the district

court erred in disallowing such evidence under the

Supreme Court's approach in Gingles. On remand, such

evidence should be admitted on the question of the

geographic concentration of the voters by race.

9 -

829 F .2d at 1563.

Despite the ruling in Carrollton Branch of NAACP, and without

arguing that the decision was wrongly decided or should be

overruled, defendants nevertheless claim that plaintiffs failed to

meet the geographic compactness requirement of Gingles because

"Bleckley County is itself a single-member district. Brief of

Appellees, p. 21 n.21. The argument is not only foreclosed by

Carrollton Branch of NAACP, but it is also undercut by Overton,̂

Austin, 871 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1989), the only authority cited by

the defendants in support_of their contention.

In Over ton, the district court held that Gingles permitted it

to order an expansion of the Austin city council from six to eight,

members to satisfy the geographic compactness standard. The

findings by the district court, including the finding on other-

grounds of no Section 2 violation, were affirmed by a majority of

the panel on appeal. The opinion of the majority, rather than the

concurring opinion of a single judge, establishes the meaning and

precedential value of Overton. Sole commissioner systems are

challengeable under Section 2.

^The geographic compactness requirement of Gingles, moreover,

arose in the context of a complaint that alleged a Section 2

violation based on "the legislative decision to^employ multimember

rather than single-member, districts in the contes e

jurisdictions." 478 U.S. at 46 (emphasis added) . Under the

circumstances, it was appropriate to require plaintiffs to PJ-0 e

geographic compactness, i.e. that single member districts could

indeed be created. But where, as here and in Carroll County, the

violation is alleged to be the use of an at-large elected sole

commissioner form of government, the imposition of a geographic

compactness requirement based on the county as a whole would be

nonsensical. The vote dilution in this case could be easily and

reasonably remedied by the creation of a five member board of

10

; -t.'-.j-u. 'J: - S v .. sA J*. •' . . . . . . . . . . , . -:u * ........ I r v . . - - . '™ I ' . v .....g

IV. Voting Is Racially Polarized

Defendants make various claims regarding the evidence of

racially polarized voting in Bleckley County. They are discussed

below.

A . Plaintiffs Analyzed all the Relevant Elections

Defendants say that plaintiffs "did not analyze the results of

any county commissioner elections or any other state or local

elections to determine if there was evidence of racial bloc voting

for the challenged mechanism." Brief of Appellees, p. 9 (emphasis

in original). Although they could not always conduct a regression

or other statistical analysis, plaintiffs did in fact "analyze"

state, county and municipal elections in Bleckley County to

determine the existence of racially polarized voting. That

analysis, which is recited in Brief of Appellants, pp. 7-13, and is

summarized in Exhibit A attached hereto, showed: few minority

elected officials; the consistent defeat of minority candidates; a

depressed level of black candidates for at-large elected, county

wide offices; racial bloc voting in county wide contests involving

viable black candidates;̂ the strong showing of candidates (Lester

commissioners similar to those which exist in the majority of

Georgia counties today.

4 One of the elections, the 1984 Democratic presidential

preference primary, could be analyzed by ecological regression.

The regression estimates, which were virtually identical to the

results reported state wide by CBS News/New York Times exit polls,

showed whites voting white, i.e. for white candidates, at the level

of 991, and blacks voting black at the rate of 61%. Plaintiffs

11

Maddox, George Wallace and J. B. Stoner) identified with white

supremacy; and an increased level, and success, of black candidates

in non or less dilutive election systems utilizing majority black

districts (board of education and city council), and in elections

with no majority vote requirement (city council). 5

Plaintiffs did not "chose not to comment" on the results of

the four statewide elections involving C. B. King, Hosea Williams,

Mildred Glover and Otis Smith. .Brief of Appellees, p. 26. To the

contrary, plaintiffs discussed the contests in their brief, Brief

of Appellants, p. 12, noted that they involved minor black

candidates who received little support from either black or white

voters, and agreed with the district court that the elections were

"simply a nullity." (R2-59-39)

County wide elections involving all white candidates are

similarly of little probative value in this case. While Gingles

conducted an exit poll at a second election, the 1988 Democratic

presidential preference primary, which showed 98% of whites voting

white, and 90% of blacks voting black. In a third election for

judge of probate, in which blacks were 13.5% of actual voters,

plaintiff Hall lost, getting 15% of the total vote. In a fourth

contest involving two black candidates, plaintiff Hall was elected

to the board of education from a 66% black district.

5 For example, during the time elections were conducted at-

large for the city council of Cochran, in which blacks are 38% of

the population, black candidates regularly got 30-40% of the vote.

(R3-85-87, R4-304, P. Exh. 26, 27, 28, 170, 174, 183, 205, 215,

227, 317, 354) However, with the exception of Basby, who was

elected initially by a plurality (39%) in a contest with two

whites, and who subsequently ran with the advantages of incumbency

or having been an incumbent, no black was ever able to win a seat

on the city council. After the method of elections was changed to

district voting, blacks were regularly elected to the two majority

black seats, a scenario strongly indicating polarized voting among

both black and white voters.

12

. .. - -' .~ ■

indicated that "only the race of the voter, not the race of the

candidate, is relevant to vote dilution analysis," 478 U.S. at 68,

that portion of the opinion was joined by only a plurality of the

Court. In addition, all the elections relied upon by the Gingles

Court in finding racially polarized voting were in fact black-white

contests. 478 U.S. at 80-3. Accordingly, courts have interpreted

Gingles as meaning that "the race of the candidate is in general of

less significance than the race of the voter - but only within the

context of an election that offers voters the choice of supporting

a viable minority candidate." Citizens for a Better Gretna v, City

_Gretna , La . , 834 F.2d 496, 502 (5th Cir. 1987). Accord, Campos

v. City of Baytown, Texas. 840 F.2d 1240, 1245 (5th Cir. 1988)("the

district court properly focused only on those races that had a

minority member as a candidate"). The all white contests in

Bleckley county that did not offer voters the choice of supporting

a viable minority candidate are simply of little use in determining

the existence of racially polarized voting.

B. Plaintiffs' Methodology Was Standard and Has Been

Approved by the Courts

The defendants, relying upon the testimony of their expert Dr.

Wildgen, claim that plaintiffs' regression analysis of the 1984

Democratic presidential primary was defective because plaintiffs'

expert Dr. Engstrom failed to apply "confidence bands." Brief of

i

- 13 -

• ? r .

Appellees, p. 28.6 It should be noted that Dr. Wildgen did the

same analysis as Dr. Engstrom - and got the same results. (R5-674)

The defendants' real quarrel, apparently, is not with the numbers

Dr. Engstrom computed but with the ecological regression method of

analysis he used. As the defendants' counsel advised the court,

"[w]e're challenging the validity...of using the ecological

regression analysis...I do not challenge the figures." (R5-464)

Also— see, the testimony of Dr. Wildgen that "I don't think it's

[ecological regression analysis] the best approach." (R5-664)

The defendants challenge to plaintiffs' methodology cannot be

seriously credited, for regression analysis has been approved as a

technique for showing racially polarized voting by both the Supreme

Court in Gingles, and this court in Carrollton Branch of NAACP.7

Moreover, Dr. Wildgen has himself used regression analysis in

concluding that racial polarization existed among voters in New

Orleans. See, Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna, La..

• ^9?t}fidence bands are a technique for determining the

reliability of regression estimates. Another test for reliability

is statistical significance.^ See, e.g. Thornburg v. Gingles,

supra, 478 U.S. at 53. In this case Dr. Engstrom found that "the

[between the race of voters and the race of

candidates] is so consistent and pronounced that it is

statistically significant at the .0001 level, meaning that there's

one in ten thousand chances that a relationship that consistent and

pronounced would occur by chance." (R4-430) The reliability of

the regression ̂ estimates was further supported by homogeneous

P^fcinct: analysis, which showed whites voting white at the level of

y/X. These estimates were also virtually identical to those

reported^state wide by CBS News/New York Times exit polls. Dr.

refill111 S est:‘'mat:es voting behavior were in fact extremely

" ^Ecological regression and homogeneous precinct analysis are

standard in the literature for the analysis of racially polarized

voting. Thornburg v. Gingles, supra, 478 U.S. at 53 n.20.

- 14 -

!»

I

& J 5

636 F.Supp. 1113, 1130 (E.D.La. 1986). Dr. Wildgen also previously

published a study on ecological regression in which he stated that

significance tests, and therefore confidence bands, "are just plain

insignificant" when applied to ecological regression analysis based

upon a population of precincts, as in this case, as distinguished

from a sample of precincts. See, Wildgen, "Adding Thornburg to

the Thicket: The Ecological Fallacy and Parameter Control in Vote

Dilution Cases," 20 Urban Lawyer 155, 169 (1988). Dr. Wildgen's

testimony in this case is contradicted by his previous publications

and testimony, Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna. La..

supr a, 663 F.Supp. at 1130, and is inherently unreliable. It is

nothing more than a red herring and should simply be ignored.

The defendants' attack on plaintiffs' homogenous precinct

analysis is also off the mark. Brief of Appellees, p. 29. While

there may be no homogeneous (90% or more) black precincts in the

county, there have been five homogeneous white precincts, and they

clearly reveal significant polarized voting by whites. In the 1984

Democratic presidential preference primary, the black candidate got

at most only 3.4% of the white vote in the five homogeneous white

precincts. The fact that whites vote as a bloc at such a high

level is extremely relevant to the Gingles formulation.

C. Plaintiffs' Exit Poll Is Reliable

The defendants claim that the exit poll conducted by

plaintiffs was unreliable because it overestimated the votes

15

received by Rev. Jesse Jackson. Brief of Appellees, p. 30-1.8

While it is true that proportionately more Jackson supporters

participated in the poll, the poll was extremely reliable in that

it virtually mirrored the order of finish of the candidates in the

election. The only differences were that the poll listed Gephardt

7th and Robertson 6th, and Haigh 13th and DuPont 12th, while

Gephart finished 6th in the election and Robertson 7th, and Haigh

12th and DuPont 13th. (P.Exh. 390) The poll is reliable and very

relevant evidence of voting patterns in Bleckley County, and it was

error for the district court to discount it.

D . A Trial Court Can Consider Evidence other than

Election Data

The defendants erroneously contend that Gingles prohibits a

trial court from considering evidence other than election data in

determining the existence of racial bloc voting. Brief of

Appellees, p. 22-3. Gingles held that polarized voting and the

extent of minority electoral success were "primary" evidence of

vote dilution, and that proof of other factors identified in the

legislative history of amended Section 2, such as the effects of

past discrimination, racial appeals in campaigns and the use of

electoral devices which enhance the opportunity for discrimination,

are supportive of, but not essential to, a minority voter's

claim. 478 U.S. at 48 n.15. Whatever the relevance of the

®The defendants claim that the poll overestimated Jackson

support by 150%. To the contrary, the absolute disparity between

the percent of the vote for Jackson in the election and in the poll

was only 7.5%. r

16

effects of past discrimination, etc. in proving a Section 2

violation, the Court never said or implied that they could not be

considered in proving polarized voting or that polarized voting

could only be proved through election data. Indeed, the Court

expressly held to the contrary.

Gingles recognized that in some cases a minority group may

never have been able to sponsor a candidate. Under such

circumstances, "courts must rely on other factors [than elections]

that tend to prove unequal access to the electoral process. 478

U.S. at 57 n .25. And, where the minority has begun just recently

to sponsor candidates, "the fact that statistics from only one or

a few elections are available for examination does not foreclose a

vote dilution claim." Id. Accord, Westwego Citizens for Be11er

Government v. Westwego, 906 F.2d 1042, 1045 (5th Cir. 1990).

Moreover, the district court in Gingles, in determining the extent

to which voting in the challenged districts was racially polarized,

considered, among other things, "the testimony of lay witnesses.

478 U.S. at 41. The district court's analysis, as well as its

findings of polarized voting (with the exception of one district),

were affirmed by the Supreme Court. There is no basis for

contending that Gingles precludes a court from considering evidence

other than election data in determining the existence of polarized

voting.

E . Testimony of Experienced Local Politicians Is Very

Relevant Evidence of Polarized Voting

The defendants are simply wrong in saying that no case law

17

~ c *£ 5 . i r . f k ^ _ r.

provides that polarized voting can be shown by the testimony of

experienced local politicians or lay witnesses. Brief of

Appellees, p. 32. Plaintiffs have cited numerous such cases in

their brief, Brief of Appellants, p. 34, e .g . , Gingles v. Edmisten,

590 F.Supp. 345, 367 (E.D.N.C. 1984), aff'd sub nom. Thornburg v.

Gingles, supra; Jackson v. Edgefield County, South Carolina School

District, 650 F.Supp. 1 176, 1 198 (D.S.C. 1986)("[e ]ven more

persuasive to the Court than the experts' quantitative analysis of

polarization on voting behavior is the testimony by the local

politicians who, through their participation in the political

processes, have the direct observation and are familiar with the

voting practices and voting patterns in Edgefield County").

The defendants' error is in thinking that polarized voting can

only be shown through statistical analysis and that evidence of how

elections actually work is irrelevant. The fact that blacks

consistently lose in county and city at-large elections but win in

county and city elections from majority black single member

districts is highly relevant evidence that voting is along racial

lines and that at-large elections dilute minority voting strength.

See, e .g . , Lodge v. Buxton, 639 F.2d 1358, 1378 (5th Cir.

1981)(finding racially polarized voting and "of particular

signi f icance. . . the fact that in the one city election in which city

councilmen were elected from single-member districts, a Black was

elected"), aff'd sub nom. Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 623

(1982); and Jackson v. Edgefield County, South Carolina, supra, 650

F.Supp. at 1198 (the success of black candidates in related single

- 18 -

member district elections "confirmed the political unity of each

racial group and the cohesiveness of its voting behavior"). To

conclude otherwise would be to ignore common sense and experience.

F . The District Court Considered only Election Data in

Determining if Voting Was Polarized

The defendants claim that plaintiffs are wrong in saying that

the district court refused to consider evidence other than election

data in determining the question of polarized voting, and that the

court in fact considered whether "'additional' evidence established

a violation of Section 2." Brief of Appellees, p. 24. The

defendants are in errot on two counts. First, plaintiffs d id point

out in their brief that the district court considered "brief[ly ] "

(the court's phrase) the various factors listed in the senate

report that were probative of vote dilution, such as the socio

economic status of blacks, etc., in connection with its

determination of Section 2 liability. Brief of Appellants, p. 28.

Second, the plaintiffs' claim was not that the district court

refused to consider the additional senate factors in connection

with Section 2 liability, but that the court refused to consider

them as evidence of racially polarized voting. The distinction is

critical, for having concluded that there was no polarized voting,

the court's consideration of the additional senate factors on the

issue of liability was an empty and meaningless exercise.

19

G. Plaintiffs are not: Required to Replicate the

Data Base and Statistical Analysis in Gingles

The data base and statistical analysis- in Gingles cannot,

and need not, be replicated in a case such as this involving a

small rural county in which the political participation of the

minority has been substantially repressed by a highly restrictive

system of elections.

The district court found "insufficient available

evidence" of polarized voting to meet the conditions for relief set

out by Gingles. (R2-59-46 n.48) Gingles, it should be remembered,

was a challenge to six multimember house and senate districts for

the North Carolina general assembly and involved 14 counties,

including the major metropolitan counties of Mecklenburg, Durham

and Wake. Given the large populations and number of jurisdictions

involved, the plaintiffs were able to collect and evaluate data

from 53 general assembly primary and general elections involving

black candidacies held over a period of three different election

years. 478 U.S. at 35 ns.1 & 2, 52-3. Because of the number of

jurisdictions and precincts, the Gingles plaintiffs were also able

to make extensive use of homogeneous precinct and ecological

regression analysis in examining the elections for polarized

voting.

By contrast, in a small rural county such as Bleckley,

election data and the opportunities for purely statistical analysis

are simply not available on the same scale as in Gingles. But that

does not foreclose a vote dilution challenge. As Gingles provides,

where election data is sparse or unavailable, a court is required

20

to look at other factors in determining the existence of polarized

voting and unequal access to the electoral process. 487 U.S. at 57

n.25. To hold otherwise would be to impose a dual standard for

Section 2 liability - one for large counties, or collections of

counties, where data was abundant and statistical analysis was

readily available, which would be subject to the statute, and

another for small counties, where data and the opportunities for

statistical analysis were less abundant or where minority political

participation had been particularly stiffled, which would be

exempted from the statute. Neither Congress nor the courts

envisioned or have sanctioned such a result.

In any event, the relevant evidence of polarized voting in

this case, despite the fact that most of it was completely ignored

by the district court, was extensive. In Rogers v. Lodge, supra,

for example, which involved a challenge to at-large elections in

Burke County, Georgia, a rural county comparable in size to

Bleckley, the Supreme Court found racially polarized voting based

upon evidence that was considerably more sparse and less compelling

than here. Unlike as in this case, no regression analysis or exit

polling of any kind was done in Rogers v. Lodge. The evidence of

polarized voting consisted entirely of: one black candidate carried

the four majority black precincts while losing in the others;

another black candidate carried three of the majority black

precincts and lost in the others; a white candidate sympathetic to *

black concerns was defeated; and, a black was elected to the city

council from a heavily black district. See, Brief of Appellants,

21

p. 36. The finding of Che district court in this case that there

was insufficient evidence of polarized voting cannot be squared

with the holding in Rogers v. Lodge, supra, 458 U.S. at 623, that

"[tjhere was overwhelming evidence of bloc voting along racial

lines" in Burke County.

V . Other Erroneous Factual and Legal Assertions

The defendants make a number of other erroneous factual and

legal assertions which are discussed briefly below.

A . Blacks Do not Prefer the Sole Commissioner System

The defendants contend that "the citizens of Bleckley County

prefer the sole commissioner form of government." Brief of

Appellees, p. 5.9 The contention is clearly not true for the

black citizens of the county, whose voting strength is diluted by

the at-large elected sole commissioner system and who seek the

implementation of a board of commissioners elected from districts.

B. The Black Community Is Politically Cohesive

In claiming that blacks in Bleckley County are not politically

cohesive, the defendants cite the testimony of their expert Dr.

Loftin for the proposition that there is "no evidence of political

organization among black citizens." Brief of Appellees, p. 34.

What Dr. Loftin actually said was that she had found no evidence of

"[£] political organization" among black citizens. (R5-

601)(emphasis added) Of course, Dr. Loftin and the defendants are

wrong. There is not only "political organization" among blacks, as

^The defendants' record cite for this proposition, R5-618,

makes no reference at all to the alleged preferences of the

citizens of Bleckley County.

22

this litigation and the record in this case demonstrate, but there

is "a political organization" in the black community - the

Concerned Citizens Committee. (R4-286, 296)

The defendants also take Dr. Engstrom's testimony out of

context when they claim he said "no determination could be made

regarding political cohesiveness in plaintiff Hall's successful

campaign for the school board." Brief of Appellees, p. 35. What

Dr. Engstrom actually said was that "if there are two black

candidates in the race, you can conclude that one is the preference

of black voters." (R4-438) What he could not determine without

"sign-in" data was which one of the blacks was most preferred by

black voters. (R4-439)10

C . Responsiveness Is not an Issue in this Case

The defendants claim that responsiveness of white elected

officials "was a valid consideration for the court" in resolving

the Section 2 claim. Brief of Appellees, p. 37. To the contrary,

the legislative history of Section 2 provides that evidence of

Although it is not possible to do regression analysis, it

is sometimes possible to estimate by simple arithmetic the minimum

level of bloc voting by blacks in the majority black districts and

thus the political cohesiveness of the black community. For

example, in the 1986 election for city council Post II, Roberson,

a black, got 492 (841) of the votes, and his white opponent got 96

(161) of the votes. (R3-85-87) According to Roberson, the

registration in the district was approximately 800 (731) black and

300 (271) white. ■(R3-85-7) A total of 588 votes were cast in the

election, meaning that some 53.51 of the registered voters turned

out (588 - 1100 = 53.51). Assuming the same level of turn out for

black and white voters, approximately 428 blacks (800 x 53.51 =

428) and 161 whites (300 x 53.5 = 161) voted. Further, assuming

that all the white voters voted for Roberson, Roberson got a

minimum of 331 black votes (492 - 161 = 331), or 671 of the black

vote. Even this unrealistically conservative estimate reveals

substantial political cohesion in the black community.

23

i.'' v ’v > . jiV TL-.'i-> i n t u ' .

responsiveness is to be avoided in Section 2 cases because at as a

highly subjective factor which "creates inconsistencies among court

decisions on the same or similar facts and confusion about the law

nr officials and voters.” H.R. Rep. No. 227, su£ra, among government officials

at 30. in addition, evidence of responsiveness cannot rebut a

plaintiffs showing of dilution under Section 2. S. Rep. No. 417,

supra, at 29 n.116. Accord, Campos v. Catv of Baytown, Texa^,

supra. 840 F.2d at 1250. Plaintiffs made no claim that defendants

were unresponsive. Accordingly, responsiveness is not an issue in

this case,

j c t-hflt- the sole commissioner system hasThe claim by defendants that tne

been used without change from the creation of Bleckley County to

the present" is incorrect. Brief of Appellees, p. 39. The

adoption of a majority vote requirement in 1964, first by the

county Democratic party and then by the general assembly, was a

major change in the sole commissioner system.!' It put it beyond

the power of the black minority to elect a candidate of its choice

by a plurality of the votes, and thus insured absolute control by

the bloc voting white majority. The adoption of the majority vote

requirement significantly enhanced the dilution of minority voting

strength, and has deterred or discouraged blacks from running for

county wide office.

” " M le “J ' L°£ m 8teStthereed m V

requirement1 ŵ is u V U to 1964.

24

The defendants also say that plaintiffs' challenge to the use

of the majority vote requirement "makes no sense because

plaintiffs did not state a separate claim that the requirement

violated Section 2 or the Constitution. Brief of Appellees, p. 49.

Plaintiffs contend that by enacting the majority vote requirement

in 1964, the general assembly reshaped at-large election systems

wherever they existed in the state, including in Bleckley County,

into more secure mechanisms for discrimination. It would be

possible, however, to conduct elections for a board of

commissioners utilizing a majority vote requirement, e _ ^ by using

fairly drawn single member districts. Properly understood,

plaintiffs' challenge to the majority vote requirement makes

perfect sense.

Conclusion

The evidence in this case meets the three part test in

Gingles. It also shows that blacks in Bleckley County are denied

equal access to the electoral process. The judgment below should

be reversed and the case remanded for the implementation of an

appropriate remedy utilizing a board of commissioners elected from

districts, or in a manner that does not dilute minority voting

strength.

ChTfstoph^r Coates

Georgia Bar No. 170980

111 West Washington Street

Milledgeville, Georgia 31061

Laughlin MacDonald, Neil Bradley

Kathleen Wilde, Mary Wyckoff

American Civil Liberties Union

44 Forsyth Street N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Attorneys for Appellants

25

I.

EXHIBIT A

NON-MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS INVOLVING VIABLE BLACK CANDIDATES

CONTEST YEAR CANDIDATE METHOD OF

ELECTION

RESULT ANALYSIS

Judge of

Probate

1984 Hall Countywide L03t Got 15% of vote.

Blacks 13.5% of

actual voters.

Democratic

Pres iden-

tial

Preference

Primary

1984 Jackson Countyvide Finished

fourth in

field of

nine

candidates

Regression and

Homogeneous

Precinct Analysis

showed Jackson got

61 % of black vote

and less than 1%

of white vote.1

Board of

Education

1986 Hall Single

member

district

Won Blacks were 66% of

District

Population.

Democratic

Pres iden

tial

Preference

Primary

1988 Jackson Countywide Finished

second in

field of

seven

candidates

Exit Poll showed

Jackson got 90% of

Black Vote and

less than 8% of

white vote.

1 These estimates

results of the 1984 CBS were virtually identical to the statewide

News/New York Times exit polls.

EXHIBIT A

II. CONTESTS IN WHICH CANDIDATES WERE STRONGLY IDENTIFIED WITH WHITE

SUPREMACY

CONTEST YEAR CANDIDATE METHOD OF

ELECTION

RESULT ANALYSIS

Governor

(Genera 1

election)

1966 Maddox Countyvide Finished

first

Got 69% of

tota 1

vote .

Democratic

Presidential

Preference

Pr imary

1968 Wallace Countyvide Finished

first

Won a

"solid"

majority.

Governor

(Primary

election)

1974 Maddox Countyvide Finished

first in

field of ten

candidates

Got 44% of

total

vote .

Lt. Governor

(Primary

Election)

1974 Stoner Countyvide Finished

second in

field of ten

candldates

Got 20% of

total

vote .

EXHIBIT A

III. MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS INVOLVING BLACK CANDIDATES

YEAR BLACK

CANDIDATE

METHOD OF

ELECTION

RESULT ANALYSIS

1972 Basby At-large Lost Got 39% of vote in contest

with one white.

1973 Basby At-large Won Got a plurality of vote (39%)

in a contest with two whites.

1975 Basby At-large L03t Got 48% of vote in a contest

with one white.

1976 Harris At-large L03t Got 22% of vote in contest

.with three whites.

1976 Howard At-large Lost Got-34% of vote in contest

with one white.

1977 Black3hear At-large L03t Got 40% of vote in contest

with one white.

1977 Basby At-large Won Got 50.5% of vote in contest

with two whites. Ran as

former incumbent.

1978 Pitts At-large Lost Got 32% of vote in contest

with one white.

1978 Hall 'At-large Lost Got 43% of vote in contest

with one white.

1979 Ba3by At-large Won Got 70% of vote in contest

with one white. Was an

incumbent.

1980 Pi t t 3 At-large Lost Got 7% of vote in contest with

two whites.

1980 Walker At-large Lost Got 20% of vote in contest

with two whites.

1981 —Basby At-large Won Unopposed, Incumbent.

1982 Walker At-large Lost Got 23% of vote in contest

with two white3.

1982 McDonald - At-large Lost Got 37% of vote in contest

with one white.

1983 Basby At-large Won Unopposed, incumbent.

YEAR

■

BLACK

CANDIDATE

—

METHOD OF

ELECTION

RESULT ANALYSIS

1984 Harr is At-large Lost Got 39% of vote in contest

vi th one white .

1985 Basby At-large "Won Unopposed, incumbent.

1986 Roberson.__" Single

member

district

Won Got 84% of vote in contest

with one white. District is

71% black.

1987 Basby Single

member

district

Won Unopposed, incumbent.

District is 71% black.

1988 Roberson Single

member

district

Won Unopposed, incumbent.

District is 71% black.

1989 Basby Single

member

district

Won Unopposed, incumbent.

District i3 71% black.

■ «v». U'-.'ris’w . *. j ‘ i O. «i'*- «I x U

!L

t.

f

(

!)

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have this day mailed a true and correct

copy of the Reply Brief of Appellants to counsel for Appellees in

envelopes addressed to them and having affixed thereto sufficient

postage prepaid thereon to ensure delivery as follows:

Mr. R. Napier Murphy

Mr. John C. Daniel, III

240 Third Street

P.0, box 1606

Macon, Georgia 31202-1606

Mr. W. Lonnie Barlow

P.0. Box 515

Cochran, Georgia 31014

This 27th day of August, 1991.

.a. .ChristO/pher Coates

Attorney for Plaintiffs