Steward v. Stanton Independent School District Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Steward v. Stanton Independent School District Brief for Appellants, 1966. 617aa235-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/975b67ac-5834-4e55-876d-1059e7485b59/steward-v-stanton-independent-school-district-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

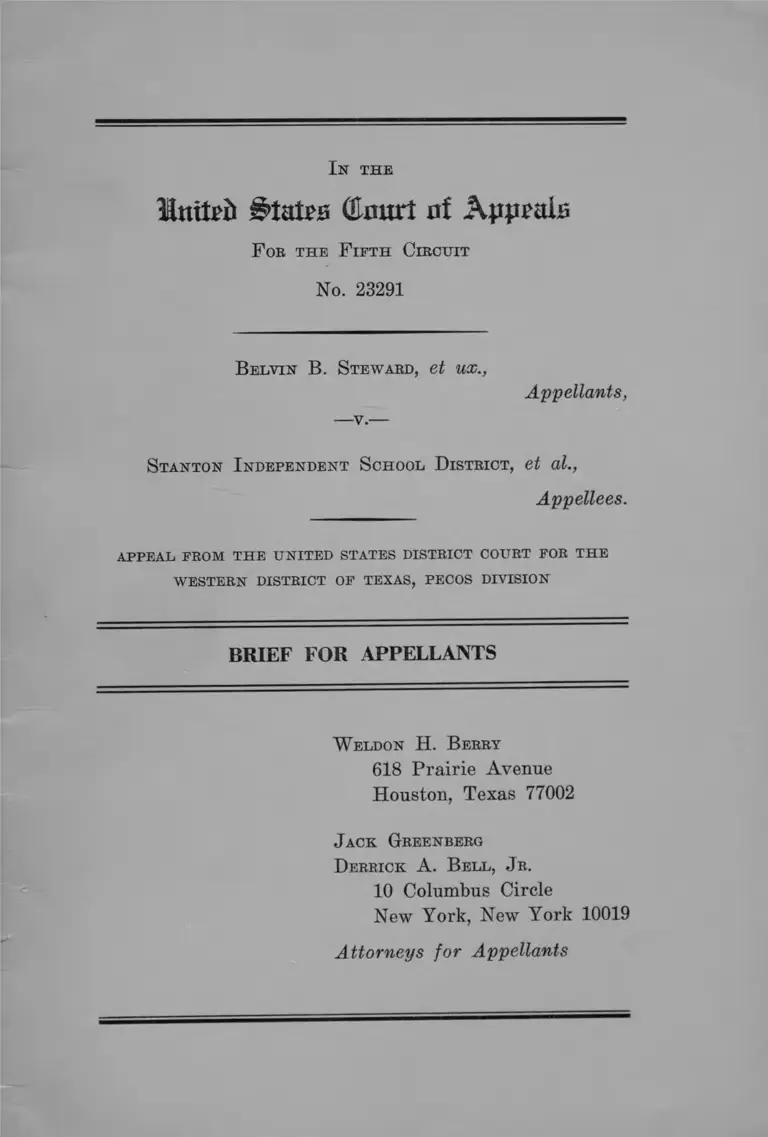

I n THE

llmteii States Court of Appeals

F oe t h e F if t h C ir c u it

No. 23291

B e l v in B . S t e w a r d , et ux.,

Appellants,

S t a n t o n I n d e p e n d e n t S c h o o l D is t r ic t , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS, PECOS DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

W e ld o n H . B e rr y

618 Prairie Avenue

Houston, Texas 77002

J a c k G r e e n be r g

D e r r ic k A . B e l l , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement .......................................................................... 1

Specification of Error .................................................... 8

A r g u m e n t —

Preliminary Statement .................................................... 9

I. Appellants, Under Generally-Applied Rules of

Proof in Racial Discrimination Cases, Sufficiently

Proved Their Dismissal by the Board Was Racially

Motivated and Violated Constitutionally-Protected

Rights ......................................................................... 13

II. School Boards Effecting Faculty Reductions Re

quired by Desegregation Must Evaluate All

Teachers, Both Incumbent and Applicants, by

Valid, Objective and Ascertainable Standards .... 20

C o n c l u s io n ....................................................................... 22

T able of C ases

Adler v. Board of Education, 342 U.S. 485 (1952) ....... 13

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F.2d

992 (4th Cir. 1940), cert, den., 311 U.S. 693 .............. 13

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) ........................... 17

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F.2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963) ....... 18

Bonner v. Texas City Independent School District, Civ.

No. 65-G-56 (S.D. Tex. 1965) ..................................... 11

Bradley, et al. v. School Board of City of Richmond,

317 F.2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963) ......................................... 20

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103

(1965)

PAGE

9

Brooks v. School District of Moberly, Mo., 267 F.2d

733 (8th Cir. 1959) .........................................11,13,14,

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ....

Bryan v. Alston, 148 F.Supp. 563 (E.D.S.C. 1957) ....

Buford v. Morganton City Board of Education, 244

F.Supp. 437 (W.D.N.C. 1965) .....................................

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F.2d 302 (5th Cir. 1963)

vacated 377 U.S. 263 (1964) ................................. 20,

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

245 F.Supp. 759 (W.D.N.C. 1965), on appeal to

Fourth Circuit (No. 10,379) .....................................

Christmas v. Board of Education of Harford County,

Md., 231 F.Supp. 331 (D.Md. 1964) ..................11,13,

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) .............................

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278

(1961) .............................................................................

Dean v. Gray-Supt. Wagoner Okla. Public Schools, Civ.

No. 5833 (E.D. Okla. 1965) .........................................

Dobbins v. County Board of Education of Decatur Co.,

Civ. No. 1608 (E.D. Tenn. 1965) .............................

Dowell v. School Board of City of Oklahoma, 244

F.Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) .............................

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958) ..............

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

328 F.2d 408 (5th Cir., 1964) .....................................

Fayne v. County Board of Education of Tipton Co.,

Civ. No. C-65-274 (W.D. Tenn. 1965) ..........................

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

242 F.Supp. 371 (W.D. Va. 1965) on appeal to Fourth

Circuit (No. 10,214) ............................. 11,13,17,18, 20,

,20

9

9

13

11

21

11

18

20

13

11

11

9

17

18

11

21

Ill

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, Va., 304

F.2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) ............................................ 20

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) .............. 9

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 (1963) .............. 19

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343 (5th Cir. 1962) ........... 18

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 428 (1963) .......... 2

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) ...................... 17

North Carolina Teacher Association v. City of Ashe-

boro Board of Education, Civ. No. C-102-G-65 (M.D.

N.C. 1965) ..................................................................... 11

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963) ....... 19

Price v. Denison Independent School District, 348

F.2d 1010 (5th Cir., 1965) ........................................... 10

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955) ......................... 17

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153 (1964) .................. 19

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) .......................... 9

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191, 196 (5th Cir. 1953) .......16, 26

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232

(1957) ...........................................................................13,14

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) ...................... 13

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir., 1965) ............................ 9

Slochower v. Board of Higher Education, 350 U.S.

551 (1956) ................................................................... 13,14

PAGE

Smith v. Morrilton School District No. 3, Civ. No. L.R.-

65-C-103, E.D. Ark. Oct. 8, 1965, on appeal to Eighth

Circuit (No. 18,243) .................................................... 11

PAGE

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 (1961) .................. 13

Wall v. Stanley County Board of Education, Civ. No.

140-S-65 (M.D. N.C. 1965) ......................................... 11

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) ....... 19

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 (1952) .................. 13

S t a t u t e

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. Section 2000(d),

et seq. ............................................................................. 9

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

Georgia Teachers and Education Association, Atlanta,

Georgia, Selected Cases Involving Subjective Per

sonnel Practices Utilized in Dismissing Educators .... 11

H.E.W., General Statement of Policies Under Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Respecting Desegre

gation of Elementary and Secondary Schools, April

1965 ................................................................................. 10

H.E.W., Revised Statement of Policies for School

Desegregation Plans under Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 ........................................................ 10

National Education Association, Report of Task Force

Appointed to Study the Problem of Displaced School

Personnel Related to School Desegregation and the

Employment Studies of Recently Prepared Negro

College Graduates Certified to Teach in 17 States,

December 1965 ............................................................11,12

North Carolina Teachers Association, Raleigh, North

Carolina, Teacher Dismissals 11

V

Memorandum of U.S. Commissioner of Education,

June 9, 1965 ................................................................. 10

Ozmon, The Plight of the Negro Teacher, The Ameri

can School Board Journal, pp. 13-14, September

1965 ................................................................................ 11

President’s Speech, N.E.A. Convention, July 2, 1965,

New York ...................................................................... 0

Southern Education Reporting Service, Statistical

Summary of School Segregation—Desegregation in

Southern and Border States (1965-66) .................... 9

PAGE

I n the

United States (tort of Appeals

F or t h e F if t h C ir c u it

No. 23291

B e l v in B . S t e w a r d , et ux.,

Appellants,

— y .—

S t a n t o n I n d e p e n d e n t S c h o o l D is t r ic t , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS, PECOS DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement

This is an appeal from a judgment (R. 34) of the United

States District Court for the Western District of Texas,

Pecos Division, denying relief to plaintiffs who were dis

missed as teachers after the only Negro school in the

Stanton Independent School District was closed.

On June 7, 1965, appellants Belvin B. Steward and

Christine S. Steward, Negro citizens of Stanton, Texas,

instituted this action against the Stanton Independent

School District of Stanton, Texas, Beryl D. Clinton, Super

intendent, and School hoard members Coats Bentley, A. P.

Harrell, Neil Fryar, Fred Holder and Stanton White

(R. 1, 39, 165). The complaint sought injunctive relief

2

against the School District’s hiring and assignment policy

under which appellants were refused contracts and dis

missed to prevent their teaching white children during

the school year 1965-66 (E. 4, 7, 8).

The School District filed an answer admitting appellants

had been employed in the district and had not been re

employed for the 1965-66 school year, and denying that

the School District’s refusal to re-employ appellants con

stituted a violation of constitutional rights (E. 14-15).

Plaintiff Belvin B. Steward is 32 years old, has a B.A.

degree in Political Science and Education from Prairie

View A. & M. College in Prairie View, Texas, and a M.A.

degree in Education and Administration from the same

college (E. 38, 44). Mr. Steward served in the Army for

three years after receiving his B.A. degree in 1955. He

was a substitute teacher for grades three through twelve

in the San Antonio Independent School District from the

fall of 1958 through May, 1959, before going to the Stanton

Elementary Colored School as a regular teacher in Sep

tember, 1959. He was appointed as the school’s head

teacher in 1961, received his M.A. degree in 1962. His

dismissal was effective in May, 1965 (E. 44, 48, 55, 58).

Plaintiff Christine S. Steward, 27 years old, obtained

a B.A. degree from Prairie View in English and Elemen

tary Education in 1959 and obtained a M.A. degree in

Elementary Education, Counselling and Guidance from the

same college in 1962. From 1959 to 1961 she taught all

subjects in the fifth grade and ninth grade English in the

Centerville Independent School District. She taught grades

three, four and five in the Stanton Elementary Colored

School from 1961 to 1965 (E. 131, 133-35, 137).

The record reveals the following facts. During the

school year 1964-65, Stanton Elementary Colored School,

3

an all-Negro school having three Negro faculty members,

two of whom are appellants, had 48 pupils. All-white

Stanton Elementary School had 557 pupils and 15 or 16

white faculty members during 1964-65. All-white Courtney

Elementary School had 70 pupils and 6 white faculty

members during the same period (R. 58, 209-10, 265).

The School District’s President, James N. Biggs, testi

fied that because “the law of the land had changed,”

Stanton High School was desegregated for the first time

during the school year 1964-65 (R. 172). Mr. Biggs also

testified that the federal Department of Health, Education

and Welfare was denying the School District money for

classes in home economics and vocational agriculture be

cause this suit challenges the School District’s desegrega

tion plan (R. 206-207).

Mr. Biggs also testified that all elementary schools were

consolidated for the school year 1965-66 in order to effect

integration and reduce expenditures. Because of the con

solidation, he reported, six teachers including all three

Negroes in the system were “dropped” (R. 202-203).1

1 Mrs. Ludora Preciphs, the third Negro teacher at the Stanton Colored

Elementary School, was not rehired for 1965-66 even though she has

thirteen years of teaching experience, and her grades were generally better

than those of the three white teachers transferred from Courtney Elemen

tary to Stanton and generally better than those of the newly hired white

teachers ( compare Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 12-b with Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 4-b,

5-b, 6-b, 7-b, 8-b, 9-b, 10-b, 11-b, 15-b, 16-b, 17-b, 18-b, 19-b, 20-b, 28-b,

29-b, 30-b). Superintendent Clinton testified, however, that in March,

1965, he had determined there were other teachers more qualified than

Mrs. Preciphs and that because she did not desire a new teaching con

tract, he did not offer her one (R. 292). Significantly, only one of the

thirteen newly hired white teachers had submitted an application to the

School District before March 11, 1965, the date of Superintendent Clin

ton’s letter of dismissal to Mrs. Preciphs and to appellants (see Plaintiffs’

Exhibits 4 through 20 excluding numbers 12, 13, 14; R. 87). Mrs.

Preciphs taught during the summer of 1965 in the Midland, Texas Head

Start Project (R. 144).

4

On March 11, 1965, Superintendent Clinton wrote a

letter thanking appellants for their “magnificent job” but

expressing his sadness that consolidation of the schools

would eliminate their jobs (R. 221-22). Consolidation of

the schools in fact eliminated no jobs. The Superintendent

admitted that some thirteen new, white teachers were

hired for the school year 1965-66, bringing the total num

ber of teachers in Stanton to the same number, i.e., 44,

that it was during 1964-65 (R. 212-13, 254, 290).

Mr. Clinton testified unequivocally that he considered

the “better grades, better transcripts, better college rec

ords” of the new white teachers in making recommenda

tions to the school board regarding Mr. Steward (R. 277).

Inexplicably, however, only one of the thirteen newly

hired white teachers had submitted an application for

employment to the School District before March 11, 1965,

the date of Mr. Clinton’s letter of dismissal to appellants

(see Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 4 through 20, excluding numbers

12, 13, 14; R. 87, 221-22). Furthermore, there was no

showing that appellants were the least qualified teachers

then employed by the School District. On May 10, 1965,

Mr. Steward and counsel appeared before the school board

in an effort to have appellants’ contract renewed (R. 96).

They were unsuccessful. The next day, May 11, Mr.

Steward met with Superintendent Clinton in another un

successful effort to secure re-employment (R. 113-18).

In response to questions from appellees’ counsel, Mr.

Steward testified that on May 11, 1965, Superintendent

Clinton said that the school board and white people did

not want Negroes teaching white children (R. 113). The

Superintendent sought to convince appellant that for the

sake of community peace and stability, he should accept

his dismissal and leave rather than file suit (R. 115-117).

5

Appellant rejected the suggestion and told the Super

intendent :

A. I asked him how did he think that I could face

the children that I had been teaching—would they

really think I was a teacher or just something else

because of the fact that I could teach them in a Negro

school but I still couldn’t take to an integrated situa

tion and work as I had been over there at the Colored

school. He said, “Just tell them that you haven’t—

they didn’t hire you and just take the easy way out.”

And I said, “No. I am not going to do that because

I don’t feel that I would be doing them any good

or anything, and I wasn’t going to sell the Negro

race out, even if I did lose a job and never be able

to get another job teaching school because of your

recommendation” (R. 116-17).2

At the trial, Superintendent Clinton sought to justify

the dismissal of Mr. Steward on what he deemed the

2 The Superintendent told appellant that Martin County Sheriff Saun

ders had taken guns away from white men downtown because “ they

wanted to do something.” He also asked Mr. Steward to reconsider his

position; otherwise the superintendent threatened he would so muddy

Steward’s name that it would be almost impossible for him to get another

job in Texas. Clinton also asked Steward not to file suit because Clinton

would lose his Job. Clinton said he had just built a nice home and thought

he could offer something to the community, but that Steward should leave

because Steward was not a homeowner and did not have anything for

which to remain. Clinton said if Steward did win the suit that the two

of them could not work together, that possibly Steward would remain

only one year but that was sufficient time for Clinton “ to get what he

wanted on” Steward. Clinton also asked Steward i f Steward realized

that “ people would blow up or have a fight” if Steward were allowed to

teach (R. 113-17). Steward further testified that “ he [Clinton] told me

that— what he said wouldn’t make any difference because it wasn’t any

body there but the two o f us and that I couldn’t swear to it, because if I

did, all he would have to do was deny it” (R. 115). Although Mr. Clinton

subsequently denied that appellants were dismissed because of race (R.

232, 268), Mr. Steward’s summary of the May 11, 1965 conversation has

never been questioned, qualified or denied.

6

latter’s undistinguished undergraduate transcript although

the superintendent admitted that Mr. Steward’s marks as

a graduate student were “far better” than his under

graduate marks (R. 269-70, 287). Superintendent Clinton

also felt it proper not to rehire Mrs. Steward because she

was to have a baby in the summer of 1965 (R. 293), and

because of her undergraduate “D’s” in English (R. 285).3

As in the case of Mr. Steward, the superintendent gave

“preference” to Mrs. Steward’s undergraduate work over

her graduate marks (R. 285). The superintendent testi

fied that Mr. Steward had “ indicated” that after the baby

came, Mrs. Steward’s place would be at home (R. 293).

Mrs. Steward testified that she intended to teach during

the 1965-66 school year and that neither she nor her hus

band had ever told anyone the contrary (R. 136).

Despite their years of teaching experience in Stanton

and the possession of master’s degrees, appellants were

not rehired for 1965-66 whereas none of the newly hired

white teachers has a master’s degree and most have less

teaching experience than appellants (see Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibits numbered 4 through 20, cf. R. 187-89). Mr. Steward’s

undergraduate grades tended to be lower than those of

the new white teachers (R. 277), but Mrs. Steward’s under

graduate grades compared favorably with those of the

new white teachers (see Plaintiffs’ Exhibits marked 4

through 20, excluding 12-a-b-c, 14-a-b-c). Both appellants

are licensed in Texas to teach grades one through twelve

under professional teaching certificates. None of the three

white teachers transferred from Courtney Elementary to

Stanton Elementary, and thus retained in the District,

3 Paradoxically, Superintendent Clinton’s letter of dismissal to plaintiffs

contained a singular subject and a plural predicate, viz., “ Certainly I

wish to extend to you sincere thanks, and congratulations for the mag

nificent job each of you have done for our community” (R. 221-22).

7

has such a professional teaching certificate (compare Plain

tiffs’ exhibits 13-a-b-c and 14-a-b-c with 28-a-b-c-d, 29-b

and 30-a-b-c). The record supplies little information as

to the qualifications of the three white teachers who were

dismissed because of consolidation except to reveal that

one, Mrs. Janelle Britton, did not have a bachelor’s degree;

another, Mr. Christian, was a new teacher; the third, Mrs.

Beryl Clinton was apparently the superintendent’s wife

(R. 154, 174-75).

As the School District President, James N. Biggs, ad

mitted, Negro teachers traditionally were given only one-

year tenure each year, but white teachers ordinarily

worked one year on probation and then received three-

year tenure (R. 181-83). While Superintendent Clinton

denied its existence (R. 221), this racial policy was also

reflected in the school board minutes (R. 255, 257-58)

and in the testimony of Mr. Steward (R. 123, 130). On

May 25, 1965, after appellants had been notified that

they would not be rehired for 1965-66, the school board

changed its racial policy so that upon the expiration

of teacher contracts then in force, all future teacher con

tracts would be limited to one year (R. 258). Superin

tendent Clinton, though conceding that the rehiring of

appellants would have subjected them to “pressures,” said

that appllants’ race was not a factor in refusing to rehire

them (R. 191, 218, 267-68); but had appellants been white,

they would have had the benefit of the three-year tenure

rule and thus could not have been summarily dismissed.

On November 30, 1965, the district court filed an opinion

finding that neither the school board nor Superintendent

Clinton had “any rule, practice or custom of refusing

employment to Negro teachers because of their race”

(R, 25) and that the school board and Superintendent

Clinton in good faith determined that the School District

8

had better qualified teachers than plaintiffs (R. 28-29).

The district court further found that the school board

hired and rehired teachers without racial discrimination

(R. 29-30) and that there was insufficient evidence to find

that plaintiffs were not rehired because of race or color

(R. 30-31). The district court made no finding, however,

regarding the racial policy of granting Negro teachers

one-year tenure and white teachers three-year tenure. The

district court concluded that, “Plaintiffs have the burden

of proof to satisfy the court from the evidence and by

its greater weight that they failed re-employment by rea

son of their color or race, and plaintiffs have failed to

discharge this burden” (R. 33).

Prom the November 30, 1965 judgment in favor of

appellees (R. 34) appellants noticed an appeal on Decem

ber 8, 1965 (R. 35).

Specification of Error

The district court erred in failing to find that appellants

were not rehired as teachers by appellees because of race

or color in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution.

9

ARGUMENT

Preliminary Statement

The ever increasing reluctance of the federal judiciary

to condone further delay in the complete desegregation of

public school systems as mandated more than a decade ago

in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483; 349 U.S.

294 ;4 together with increasing implementation of the 1964

Civil Rights Act,5 have resulted in a small, but noticeable

increase in pupil desegregation6 and, as a result, increasing

attention on faculty desegregation. As Negro students ob

tain transfers from all-Negro to formerly all-white schools,

and the formerly all-Negro schools are closed or integrated,

Negro teachers in Texas as elsewhere in the South

have been summarily dismissed rather than trans

ferred along with Negro students or employed and as

signed without regard to race. This policy has alarmed the

President of the United States,7 concerned the United

4 Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965); Bradley v. School Board of

Richmond, 382 U.S. 103 (1965); Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir.,

1965) ; Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d

729 (5th Cir., 1965); Dowell v. School Board o f Oklahoma City, 244

F. Supp. 971 (W.D.Okla. 1965).

6 42 U.S.C. Section 2000(d), et seq.

6 See Southern Education Reporting Service, Statistical Summary of

School Segregation— Desegregation in Southern and Border States (1965-

66) .

7 Speech, N.E.A. Convention, July 2, 1965, New York. The President

said:

“ For you and I are both concerned about the problem of the dis

missal of Negro teachers as we move forward— as we move forward

with the desegregation of the schools of America. I applaud the

action that you have already taken.

“ For my part, I have directed the Commissioner o f Education to

pay very special attention in reviewing the desegregation plans, to

guard against any pattern of teacher dismissal based on race or

national origin.”

10

States Department of Health, Education and Welfare,8

been the subject of intensive studies by national teacher

8 The Department’s General Statement o f Policies Under Title VI of

the Civil Eights Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation o f Elementary

and Secondary Schools, published in April 1965, inter alia, requires the

desegregation of school faculties (the H.E.W. Policies were adopted by

the Fifth Circuit as minimum school desegregation standards and pub

lished as an appendix to Price v. Denison Independent School District,

348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965)). The United States Commissioner of

Education in response to numerous complaints that Negro teachers were

being dismissed or released by school boards seeking to avoid faculty

desegregation, published a memorandum on June 9, 1965, and distributed

same to his staff and to the chief school officers in every State. He re

ported that the complaints were being investigated, that the policies or

practices complained of were in direct violation o f Title V I of the 1964

Civil Rights Act, and the General Statement and Policies published in

April 1965. The memorandum concluded:

“ The statement of policies, as you know, requires desegregation

plans to contain provisions concerning desegregation of school facul

ties. A school district cannot avoid the requirement that it desegregate

its faculties by discriminatorily dismissing or releasing its Negro

teachers. Nor can a freedom of choice plan be deemed ‘free’ if in

direct pressure is placed on Negro students to forego rights under

such a plan by threatening Negro teachers with loss of their jobs,

should Negro students leave Negro schools to attend desegregated

schools.”

In March, 1966, the Department issued its Revised Statement o f Policies

for School Desegregation Plans under Title V I of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, which provides in §181.13 that the effects of past discriminatory

practices in staff assignments must be corrected; that staff may not be

dismissed or not rehired on racial grounds; that patterns of staff assign

ments should reflect desegregated staff where the student body is desegre

gated; that staff o f closed schools should be reassigned to other schools

where their race is in the minority. Most pertinently, §181.13(c) stated

inter alia:

In any instance where one or more teachers or other professional

staff members are to be displaced as a result of desegregation, no staff

vacancy in the school system may be filled through recruitment from

outside the system unless the school officials can show that no such

displaced staff member is qualified to fill the vacancy. I f as a result

of desegregation, there is to be a reduction in the total professional

staff o f the school system, the qualifications o f all staff members in

the system must be evaluated in selecting the staff members to be

released.

11

groups,9 and generated a growing number of lawsuits.10

This process of pupil desegregation and teacher dis

missal has recently been reported on in great detail by

the National Education Association, which reviewed the

problem in the following terms:

“ Concern with faculty integration is becoming acute

because of current practices. Typically, whenever

twenty or twenty-five Negro pupils are transferred

from a segregated school, the Negro teacher left

without a class is in many cases dismissed rather

than being transferred to another school with a

vacancy. When all the pupils attending small Negro

9 National Education Association, Washington, D. C., “ Report o f Task

Force Appointed to Study the Problem of Displaced School Personnel

Related to School Desegregation and the Employment Studies of Recently

Prepared Negro College Graduates Certified to Teach in 17 States” De

cember 1965; North Carolina Teachers Association, Raleigh, North Caro

lina “ Teacher Dismissals” ; Georgia Teachers and Education Association,

Atlanta, Georgia, “ Selected Cases Involving Subjective Personnel Prac

tices Utilized in Dismissing Educators.” See also, Ozmon, “ The Plight

o f the Negro Teacher” , The American School Board Journal, pp. 13-14,

September, 1965.

10 Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, 242 P. Supp. 371

(W.D. Va. 1965) on appeal to Fourth Circuit (No. 10,214); Christmas

v. Board of Education o f Harford County, Md., 231 F. Supp. 331 (D.C.

Md. 1964); Buford v. Morganton City Board o f Education, 244 F. Supp.

437 (W.D.N.C. 1965) ; Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board o f Educa

tion, 245 F. Supp. 759 (W.D.N.C. 1965), on appeal to Fourth Circuit

(No. 10,379); Smith v. Morrilton School District, No. 3, Civ. No. LR.-65-

C-103, E.D. Ark., Oct. 8, 1965, on appeal to Eighth Circuit (No. 18243);

Dean v. Gray— Supt. Wagoner Oklah. Public Schs., Civ. No. 5833 (E.D.

Okla. 1965); Brooks v. School District of City o f Moberly, Mo., 267 F.2d

733 (8th Cir. 1959).

The following cases have been filed, North Carolina Teacher Associa

tion v. City o f Asheboro Board of Education, Civ. No. C-102-G-65 (M.D.

N.C. 1965); Wall v. Stanley County Board of Education, Civ. No. 140-

S-65 (M.D.N.C. 1965) ; Dobbins V. County Board of Education of

Decatur Co., Civ. No. 1608 (E.D. Tenn. 1965) ; Fayne v. County Board

o f Education of Tipton Co., Civ. No. C-65-274 (W.D. Tenn. 1965);

Bonner v. Texas City Independent School District, Civ. No. 65-G-56

(S.D. Tex. 1965).

12

schools are reassigned to previously white schools,

principals as well as an increased number of teachers

are often faced with the problem of relocation. The

1964 summer crisis caused by the growing threat and

the actual loss of positions brought a stream of pro

tests and calls for assistance to the NEA’s Commis

sion on Professional Eights and Responsibilities”

(P- 7).

“As has been demonstrated, ‘white schools’ are

viewed as having no place for Negro teachers. As

a result, when Negro pupils in any number transfer

out of Negro schools, Negro teachers become surplus

and lose their jobs. It matters not whether they

are as well qualified as, or even better qualified than,

other teachers in the school system who are retained.

Nor does it matter whether they have more seniority.

They were never employed as teachers for the school

system—as the law would maintain—but rather as

teachers for Negro schools” (p. 13).11

The deprivation of constitutional rights threatened by

these dismissals warrants careful scrutiny by this Court

for only by such inquiry can the constitutional rights of

Negro teachers be assured. It is from this perspective

that the issues raised by this case must be viewed. It

is with this background that the contested dismissals

must be examined. * 9

11 “ Report of Task Force Appointed to Study the Problems of Dis

placed School Personnel Related to School Desegregation,” see note

9, supra. The study was conducted under the auspices o f the National

Education Association and financed jointly by the Association and a grant

from the United States Office o f Education, Department o f Health, Edu

cation and Welfare.

13

I.

Appellants, Under Generally-Applied Rules of Proof

in Racial Discrimination Cases, Sufficiently Proved Their

Dismissal by the Board Was Racially Motivated and Vio

lated Constitutionally-Protected Rights.

The law is clearly established that public servants or

employees may not, consistent with the Constitution, be

deprived of the right to pursue their profession on the

basis of some frivolous, arbitrary or racially discrimina

tory ground. Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368

U.S. 278 (1961); Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488, 495-96

(1961); Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232

(1957); Slochower v. Board of Education, 350 U.S. 551

(1956); Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 (1952). Negro

teachers seeking relief against interference with their pro

fessional careers based on race frequently have been in

cluded within the protection of these rights. Shelton v.

Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960); Alston v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 112 F.2d 992 (4th Cir. 1940); Bryan v.

Alston, 148 F. Supp. 563, 567 (E.D.S.C. 1957) (dissent).

The Eighth Circuit has clearly indicated that the scope

of constitutional protection encompasses Negro teachers,

protecting them from arbitrary, unreasonable, or racially

motivated dismissal during the transition to desegregated

schools. Brooks v. School District of City of Moberly, Mo.,

267 F.2d 733, 740 (8th Cir. 1959). See also, Franklin v.

County School Board of Giles County, 242 F. Supp. 371

(W.D.Va. 1965); Christmas v. Board of Education of

Harford County, 231 F. Supp. 331 (D.Md. 1964).

Conceding that certain definite standards or criteria

are permissible, Adler v. Board of Education, 342 U.S. 485,

493 (1952), officers of a state, in applying such standards,

14

“cannot exclude an applicant when there is no basis for

their finding that he fails to meet these standards or when

their action is invidiously discriminatory.” Schware v.

Board of Bar Examiners, supra, at 239.

Thus, having the affirmative burden to accord equal

protection and due process to Negro teachers, a school

board which, in the process of desegregating its system,

closes a Negro school and dismisses the whole faculty

should carry the affirmative burden of showing this result

was not racially motivated and that the Negro teachers

dismissed were replaced by teachers judged superior by

objective and readily measurable standards. Cf. Schware

v. Board of Bar Examiners, supra; Slochower v. Board

of Education, supra; Brooks v. School District of City of

Moberly, Mo., supra at 740.

On this record, however, it is evident that appellants

and the third Negro faculty member of the abandoned

Negro elementary school were dismissed without any

thought of offering them teaching positions in the deseg

regated elementary school. Superintendent Clinton testi

fied unequivocally (1) that he considered the “better

grades, better transcripts, better college records” of the

new white teachers in making recommendations to the

school board regarding Mr. Steward and (2) that he had

determined in March, 1965 that there were more qualified

teachers than Mrs. Preciphs, the third Negro faculty mem

ber (pp. 277, 292). Since only one of the thirteen newly

hired white teachers had submitted an application to the

School District before March 11, 1965, the date of super

intendent’s letter of dismissal to appellants and Mrs.

Preciphs (see Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 4 through 20, excluding

numbers 12, 13, 14; R. 4-5, 87, 221-22), it is patently clear

that no comparison between the new white teachers and

the Negro teachers was ever made before the dismissals.

15

Furthermore, the dismissals resulted in no reduction in

the number of teachers employed by appellees in that the

same number, i.e. 44, are employed for 1965-66 as were

employed during 1964-65 (E. 212-13, 254, 290). Appellants

are more experienced teachers than most of the thirteen

newly hired white teachers; both appellants have master’s

degrees but none of the new white teachers has one (see

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits numbers 4 through 20; cf. E. 187-89).

Appellants possess Texas professional teaching certificates

to teach grades one through twelve but none of three

white teachers transferred from Courtney Elementary to

Stanton Elementary, and thus still employed by appellees,

has such a certificate (compare Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 13-a-b-c

and 14-a-b-c with 28-a-b-c-d, 29-b and 30-a-b-c). Of the

three white teachers dismissed because of consolidation,

one did not have a bachelor’s degree and another was the

superintendent’s wife (E. 174-75).

Although the superintendent admitted that Mr. Steward’s

marks as a graduate student were “ far better” than the

latter’s undergraduate marks, the superintendent sought

to justify the dismissal on what he deemed to be Steward’s

undistinguished undergraduate transcript (E. 269-70, 287).

The superintendent also felt it proper not to rehire Mrs.

Steward on the basis of her undergraduate transcript and

because she was to have a baby in the summer of 1965

(E. 285, 293). Mr. Steward’s undergraduate grades tended

to be lower than those of the newly hired white teachers

(E. 277), but Mrs. Steward’s undergraduate marks com

pared favorably with those of the new teachers (see Plain

tiffs’ Exhibits marked 4 through 20, excluding 12-a-b-c,

14-a-b-c).

Despite the superintendent’s professed concern for eval

uation of appellants’ undergraduate marks vis-a-vis the

undergraduate grades of the new white teachers, it must

16

be emphasized that not only did such an evaluation not take

place prior to appellants’ dismissal (R. 87, 221-22, 277,

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 4 through 20, excluding numbers 12,

13, 14) but also that appellants were dismissed in the con

text of a racially discriminatory tenure policy. The School

District President, James N. Biggs, admitted that Negro

teachers traditionally were given only one-year tenure each

year but that white teachers ordinarily worked one year on

probation and then received three-year tenure (R. 181-83).

Expectedly, Superintendent Clinton disputed the existence

of such a policy (R. 221), but the school board minutes

(R. 255, 257-58) and Mr. Steward’s testimony (R. 123, 130)

reflect it. On May 25, 1965, after appellants had been

notified that they were dismissed, the school board changed

its discriminatory racial policy so that upon the expira

tion of teacher contracts then in force, all future teacher

contracts would be limited to one year (R. 258). Had ap

pellants been white they would have been given three-year

contracts after their respective first years of teaching;

thus Mr. Steward would have received a three-year con

tract in 1960, another in 1963 and would have had one

year remaining of his second three-year contract at the

time he was dismissed. Mrs. Steward would have received

her first three-year contract in 1962, after her first year

of teaching, and would have been eligible for her second

three-year contract at the time of her dismissal. Of course,

the superintendent denied that appellants’ race was a fac

tor in their dismissals (R. 267-68) but he conceded that

appellants would have been subject to “pressures” if they

had been rehired (R. 218) and he has never denied making-

threats to ruin Steward if this suit was instituted (see

R. 113-17).

In view of (1) the superintendent’s undenied hostility

toward Mr. Steward; (2) the summary dismissal of appel

lants in the absence of any evidence to show they were the

17

least qualified teachers in the School District; (3) the

superintendent’s callous disregard for truth in that he

stated he had compared Mr. Steward’s grades against those

of the new white teachers before appellants’ dismissals but

in fact only one new white teacher had applied at the

time of appellants’ dismissals; (4) and the racially dis

criminatory teacher tenure policy in force at the time of

appellants’ dismissals, it is submitted that appellants were

the victims of a blatantly racist policy to exclude Negro

teachers from desegregated teaching positions.

Traditionally, where racial discrimination is charged,

courts have required more than mere pious denials of

racial bias to absolve state officials alleged to have violated

Fourteenth Amendment rights. In criminal cases where

racial discrimination in jury selection is alleged, federal

and state courts, upon a showing that Negroes are eligible

but have not been chosen, lay on the State the burden of

proving jury discrimination does not exist. See Eubanks

v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958); Reece v. Georgia, 350

U.S. 85 (1955); Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953);

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935). Without such a

rule, even the most flagrant instances of racial discrimina

tion in jury exclusion would remain beyond the remedy

of the courts and the Constitution. Norris v. Alabama,

supra, at 598.

The court below found that appellants failed to show

racial discrimination by the “greater weight” of proof

(R. 33).

To the extent that the Superintendent’s denials of dis

crimination and the manifestations of bias reflected by the

record are in conflict, the cases indicate that the issue

must be resolved in plaintiffs’ favor.

Without express mention of the burden of proof prob

lem, the district court in Franklin v. County School Board

18

of Giles County, 242 F. Supp. 371, 374 (W.D.Va. 1965),

carefully scrutinized and rejected the Superintendent’s

basis for selecting teachers, where the teacher force was

reduced from 186 to 179 teachers as a result of the closing

of Negro schools and the 7 teachers released were all

Negroes. Similarly, in Christmas v. Board of Education

of Harford County, 231 F. Supp. 331, 337 (D.Md. 1964)

the court ruled:- “ . . . the failure to hire a single Negro

applicant for the desegregated schools, although the

qualifications of some of these applicants are obvious and

admitted, justified plaintiffs’ skepticism, and requires that

an injunction be issued prohibiting discrimination on the

basis of race in hiring new teachers.”

Significantly, in both the Harford and Giles County de

cisions, supra, the district courts carefully noted that the

abrupt reductions in the ranks of Negro teachers cor

responded with school desegregation efforts. This Court

has considered past racially discriminatory practices and

laws as crucial in Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343 (5th Cir.

1962); Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F.2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963);

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 328

F.2d 408 (5th Cir. 1964); and was particularly appropriate

in the Harford and Giles County cases where the school

board, did not immediately desegregate the schools, but

delayed taking affirmative action until required by court

order. Similar attention is appropriate here where the

Board delayed initiation of school desegregation for more

than a decade until threatened with litigation or the loss

of federal funds.

In summary, the Superintendent’s contention that the

dismissal of all Negro teachers was not based on race is

irreparably compromised by both the record which clearly

evidences the presence of invalid racial considerations in

the School District, and the School Districts maintenance

19

of segregated schools long after it was apparent to all

that the policy irreparably denied Negro pupils their con

stitutional right to a desegregated education. Indeed, the

Superintendent is in no better position than the State

officials who contended that the Negroes arrested and con

victed while seeking desegregated service in privately

owned eating places were not prosecuted because of race.

Reversing such convictions, the Supreme Court noted the

presence of segregation statutes, regulations and policies,

and held that because of the continued presence of State-

sponsored segregation requirements, the officials’ denials

that their actions were racially motivated would not be

heard. Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963).

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 TT.S. 267 (1963); Robinson v.

Florida, 378 U.S. 153 (1964).

The applicability of the rationale of these cases to the

instant case is inescapable. The history of discrimination

by the School Board, particularly in employment and as

signment of teachers and school personnel, warrants here

an affirmative showing that appellants were not denied

employment because of race. Failure of the court below

to require such showing reduced the rights of the Negro

teachers involved to sterile pronouncements without mean

ing or force. Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526

(1963).

20

II.

School Boards Effecting Faculty Reductions Required

by Desegregation Must Evaluate All Teachers, Both In

cumbent and Applicants, by Valid, Objective and Ascer

tainable Standards.

A. To subject appellants to different standards or cri

teria than that required of white teachers in the system

unquestionably denies them equal protection of the laws.

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, supra,

at 374. See also Bradley v. School Board of the City of

Richmond, 317 F.2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963); Green v. School

Board of the City of Roanoke, 304 F.2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962);

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F.2d 302, 304-305 (5th Cir. 1963),

vacated 377 U.S. 263. Here, plaintiffs, unlike their white

counterparts who had taught in the school system during

prior years, were considered as being out of a job and,

assuming they were considered at all, were compared for

vacancies in the Stanton Elementary School along with

new white applicants (R. 277). White teachers already

assigned to the Stanton Elementary School apparently were

not similarly compared.

Where the desegregation process results in no reduc

tion in faculty size (R. 212-13, 254, 290), fundamental con

cepts of fairness require selection of all teachers based

on an objective evaluation of their qualifications. More

over, as the district court noted in Franklin v. County

School Board of Giles County, supra, at 374, “the making

of such an evaluation is strong evidence of good faith,

see Brooks v. School District of City of Moberly, Mo., 267

F.2d 733, 736, . . . ” Teacher morale, no less than law and

order, while desirable, may not be maintained at the sacri

fice of constitutional rights. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1,

16 (1958).

21

B. Appellants were denied due process and equal pro

tection of the laws when required to compete with new

white teachers although other white teachers similarly-

situated as plaintiffs apparently were not similarly ap

praised. Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

supra; Calhoun v. Latimer, supra.

As indicated above, it was the School Board’s failure

to compare the qualifications of all teachers for vacancies

in the school system which was held repugnant to the con

stitutional rights of Negro teachers in Franklin v. County

School Board of Giles County, supra, at 374. It should

also be condemned here. Applying such standards to the

school system required that Negro teachers who formerly

taught in the Stanton Colored School be fairly weighed

and considered with all teachers teaching grades for which

the Negro teachers were qualified rather than being con

sidered as dismissed teachers competing only for vacancies

in the school system.

Failure of the court below to require this comparison

and the same objective appraisal of white teachers simi

larly situated as plaintiffs and members of their class con

stituted an abuse of discretion requiring reversal of the

lower court’s decision.

22

CONCLUSION

Appellants respectfully pray that this Court reverse the

holding of the lower court and remand the case with in

structions requiring the reinstatement of the appellants.

If a reduction in teacher force is required, the same stand

ards or criteria are to be applied to all teachers and ap

plicants, and after such appraisal, should appellants be

refused employment, the Board must come forth with clear

and convincing evidence to show that those denied employ

ment were accorded due process and equal protection of

the laws. Appellants are entitled both to damages for the

economic losses resulting from the Board’s action and to

their costs and attorneys’ fees.

Respectfully submitted,

W e l d o n H . B e r b y

618 Prairie Avenue

Houston, Texas 77002

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

D e b e ic k A. B e l l , J e .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

ME1LEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C.-*S§g»'2'»