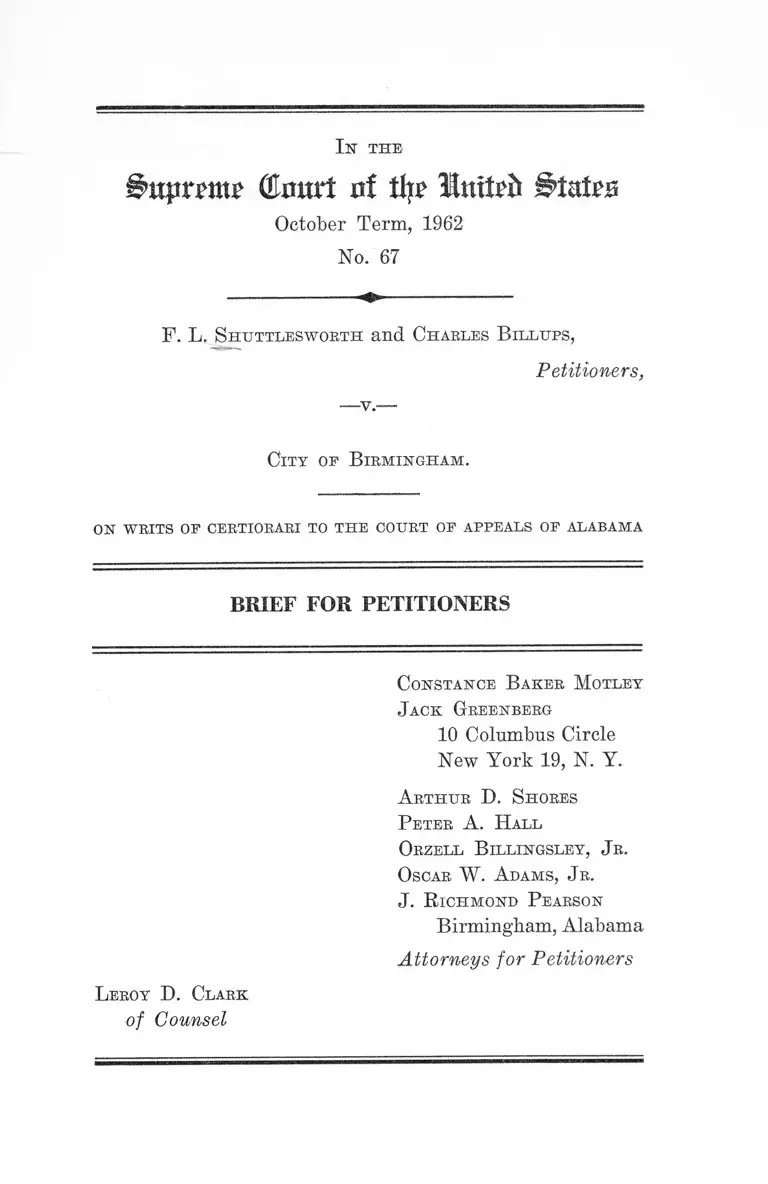

Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1962

17 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Brief for Petitioner, 1962. 67bb8654-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/97d3865d-07ae-4e59-b91d-351b57c730d5/shuttlesworth-v-birmingham-al-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Glmtrt of % lotted

October Term, 1962

No. 67

F. L, S hu ttlesw orth and Charles B illu ps ,

Petitioners,

Cit y op B ir m in g h a m .

ON -WRITS OP CERTIORARI TO T H E COURT OP APPEALS OP ALABAM A

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

C onstance B aker M otley

J ack G reenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

A rth u r D . S hores

P eter A . H all

O rzell B illingsley , Jr.

Oscar W . A dams, Jr.

J. R ichm ond P earson

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioners

L eroy D . Clark

of Counsel

INDEX

PAGE

Opinions Below .............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction.......................... 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved......... 2

Question Presented........................................................... 3

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 3

A rgument .................................................................... 7

I. Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Imperatives

Require Reversal of These Convictions ................. 7

A. There Is No Evidence in This Record on

Which These Convictions May Be Affirmed 7

B. This Record Discloses Only an Exercise of

Constitutionally Protected Freedom of As

sembly and Speech.......................................... 9

C. The Ordinance for Violation of Which Peti

tioners Were Convicted Is Constitutionally

Vulnerable on the Grounds of Vagueness .... 12

Co n c l u s io n ........................................................................................ 13

T able oe Cases

Briscoe v. State of Texas, 341 S. W. 2d 432 .................. 8

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 ................................ 13

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 ............... 13

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 .... 13

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 H. S. 569 .......................... 11

11

PAGE

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315.................................. 11

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 .......................8, 9,10,12

Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U. S. 325 .................................. 11

Johnson v. State of Texas, 341 So. 2d 434 ................... 8

King v. City of Montgomery,------A la .------- , 128 So. 2d

341....................................................................................... 8

Kovaes v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77 .......................................... 11

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 .................................. 10

National Labor Relations Board v. Fansteel Metallurgi

cal Corp., 306 U. S. 240 .................................................. 8

Rucker v. State of Texas, 341 So. 2d 434.......................... 8

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 ...................................... 13

Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 4 7 .......................... 12

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, 4 .......................... 11,12

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199............... 9

Tucker v. State of Texas, 341 So. 2d 433 ....................... 8

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 ................... 9

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 .................................. 13

O thek A uthorities

Pollitt, Duke L. J., Dime Store Demonstrations: Events

and Legal Problems of First Sixty Days, 315 (1960) .. 7, 8

In the

(&nmt nt % l u t t ^

October Term, 1962

No. 67

F. L. S hu ttlesw orth and Chables B illu ps ,

Petitioners,

— v.—

C ity of B ir m in g h a m .

ON W HITS OF CERTIORARI TO T H E COURT OF APPEALS OF ALABAM A

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The opinions of the Court of Appeals of Alabama are

reported at 134 So. 2d 213 (Shuttlesworth, R. 43) and 134

So. 2d 215 (Billups, R. 67).

Jurisdiction

The judgments of the Alabama Court of Appeals were

entered on May 30, 1961 (Shuttlesworth, R. 44; Billups,

R. 67).

Application for rehearing before the Court of Appeals

of Alabama was denied on June 20, 1961 (Shuttlesworth,

R. 45; Billups, R. 68). A petition to the Supreme Court of

Alabama for Writ of Certiorari was denied on September

25, 1961, and application for rehearing was overruled on

November 16, 1961 (Shuttlesworth, R. 46, 51; Billups,

2

R. 68). The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant

to 28 United States Code, §1257 (3), petitioners having

asserted below, and asserting here, the deprivation of his

rights, privileges and immunities secured by the Consti

tution of the United States.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the followTing constitutional provision:

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States.

The case also involves the following provisions of the

General Code of Birmingham of 1944:

“ Section 824. It shall be unlawful for any person to

incite, or aid or abet in, the violation of any law or

ordinance of the city, or any provision of state law,

the violation of which is a misdemeanor.”

“ Section 1436 (1944), A fter Warning. Any person who

enters into the dwelling house, or goes or remains on

the premises of another, after being warned not to do

so, shall on conviction, be punished as provided in

Section 4, provided, that this Section shall not apply

to police officers in the discharge of official duties.”

“ Section 369 (1944), Separation of races. It shall be

unlawful to conduct a restaurant or other place for the

serving of food in the city, at which white and colored

people are served in the same room, unless such white

and colored persons are effectually separated by a

solid partition extending from the floor upward to a

distance of seven feet or higher, and unless a separate

entrance from the street is provided for each compart

ment” (1930, Section 5288).

3

Question Presented

Alabama has convicted petitioners of “ inciting] or

aid[ing] or abet [ting] another person to go or remain on

the premises of another after being warned . . . ” The

record showed essentially that petitioner Shuttlesworth

“asked for volunteers to participate in the sit-down dem

onstrations” and that petitioner Billups was present at

this request. There was no evidence that either persuaded

anyone to violate any law, or that anyone following peti

tioners’ suggestions did violate any law, valid under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

A Birmingham ordinance requires racial segregation in

restaurants.

In convicting and sentencing petitioners respectively to

180 and 30 days hard labor, plus fines, has Alabama denied

liberty, including freedom of speech, secured by the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Statement of the Case

Petitioners, Rev. F. L. Shuttlesworth and Rev. Charles

Billups, were convicted by the Recorder’s Court of the City

of Birmingham, Alabama and, upon a trial de novo, by an

Alabama Circuit Court of a violation of Section 824, Gen

eral City Code of Birmingham, 1944 (R. 8, 59).1 The City’s

complaint alleged that petitioners, in violation of Section

824, “ did incite or aid or abet” the violation of another

City ordinance, Section 1436, which defines the crime of

trespass after warning (R. 2, 53).2 Petitioner Shuttles-

1 See page 2, supra, for text of ordinance.

2 See page 2, supra, for text of ordinance.

4

worth was fined $100 and sentenced to 180 days hard labor

for the City while lesser penalties, $25 and 30 days, were

imposed on Billups (R. 8, 59).

The convictions, appealed to the Alabama Court of Ap

peals, were affirmed, followed by unsuccessful attempts to

secure review by the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 43-45,

46-51, 66-68, 69).

The City undertook to sustain its burden of proof on

the testimony of a single witness who did not personally

witness any of the facts to which he testified but which the

Circuit Court found sufficient for conviction. The witness,

Charles L. Pierce, a Birmingham City detective, testified,

over the repeated objections of petitioners’ counsel, that he

was present at petitioners’ trial in Recorder’s Court when

two of the persons whom petitioners allegedly incited to

violate a City ordinance, students James Gober and James

Albert Davis, testified concerning the instant charge (R.

20-23).

The testimony Detective Pierce heard, and which forms

the sole basis upon which the convictions were sustained,

follows:

Gober testified that on March 30,1960 he went to the home

of Rev. Shuttlesworth where several others, including peti

tioners, were present and discussed sit-in demonstrations

by Negro students (R. 27-28). Rev. Shuttlesworth partici

pated in the discussion (R. 28). He then asked for “ volun

teers” for sit-in demonstrations (R. 29). Gober referred

to a “ list” but didn’t know who had made it (R. 29-30).

James Albert Davis testified that petitioner Billups came

to Daniel Payne College, where Davis and Gober were

students, and took Davis in his car to Shuttlesworth’s house

(R. 31). When Davis arrived, several persons were there,

including Shuttlesworth, his wife, and a number of other

5

students from the College (R. 31). Rev. Shuttlesworth

asked for “volunteers” and he (Davis) “ volunteered” to

go to Pizitz at 10:30 and take part in a sit-in demonstration

(R. 31). Davis testified a list was made, hut he, also, did

not know who made the list (R. 31). Finally, Davis testified

that Rev. Shuttlesworth “ told him or made the announce

ment at that time that he would get them, out of jail”

(R. 31-32). To this testimony the detective added that he

knew it was a fact that Gober and Davis did participate

in a sit-in demonstration on March 31, 1960 (R. 33).

Upon the foregoing, petitioners were adjudged guilty of

having incited or aided or abetted Gober, Davis, and other

students to violate the trespass after warning ordinance

(R. 40).

At every opportunity, petitioners urged the Fourteenth

Amendment due process claim now before this Court. They

first moved to strike the complaint (R. 3), then demurred

(R. 4), moved to exclude the testimony (R. 6) and for new

trial (R. 11). Again, in assignment of errors in the Court

of Appeals (R. 41-42) and petition for certiorari in the

Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 47-50) a violation of due

process guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Federal Constitution was urged.

Petitioners’ due process claim is that: 1) Section 824,

General Code of Birmingham, as applied to them, deprives

them of freedom of assembly and speech; 2) there is no

evidence at all that petitioners incited, aided or abetted any

violation of law or that a violation of law in fact occurred;

and 3) Section 824 as applied is so vague as to constitute

a denial of due process of law in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

The only court which rendered an opinion was the Ala

bama Court of Appeals (R. 43-44, 67). It limited review to

6

considering the sufficiency of the evidence to support a

conviction for violation of Section 824. In Rev. Shuttle s-

worth’s case that court found it sufficient that “ . . . ‘Shuttles-

worth asked for volunteers, and that there were some

volunteers to take part in sit-down demonstrations’ and

that Shuttlesworth promised to get them (the students) out

of jail” (R. 44). The court then held that, “A sit-down

demonstration being a form of trespass after warning,

denotes a violation of both state law and especially of Sec

tion 1436 of the City Code” (R. 44). Having found that

the evidence was sufficient to sustain the conviction on the

ground of incitement, the court then ruled that no Four

teenth Amendment free speech rights were involved. It

held that petitioners “ counseled the college students not

merely to ask service in a restaurant, but urged, convinced

and arranged for them to remain on the premises pre

sumably for an indefinite period of time” (R. 44). The

court found the situation here analogous to illegal sit-down

strikes in the automobile industry (R. 44).

Rev. Billups’ conviction was upheld on the authority of

the Shuttlesworth case, except for the following addition:

On March 30, 1960 Rev. Billups went to Daniel Payne Col

lege in a car where he picked up one of the students, Davis,

and drove him to the home of Rev. Shuttlesworth where

several people had gathered and where Rev. Billups also

was present (R. 67).

7

A R G U M E N T

I.

Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Imperatives Re

quire Reversal of These Convictions.

A. There Is No Evidence in This Record on Which

These Convictions May Be Affirmed.

The Alabama courts have held the facts set forth above

sufficient to convict petitioners of inciting a violation of an

ordinance which provides that, “ Any person who . . . goes

or remains on the premises of another, after being warned

not to do so, shall on conviction, be punished. . . . ”

Petitioner Shuttlesworth asked for “volunteers” to par

ticipate in a sit-in demonstration.3 But there is no evidence

that he incited these volunteers to “ remain on the premises

of another, after being warned not to do so.” Moreover,

there is no evidence in this record to sustain a finding that

these volunteers did in fact remain on the premises of

another after being duly warned not to do so.

Even the Alabama Court of Appeals recognized that

there was no evidence to support the charge and so it

surmised that petitioners “ counseled the college students

not merely to ask service in a restaurant, but urged, eon-

3 See, Pollitt, Duke L. J., Dime Store Demonstrations: Events

and Legal Problems of First Sixty Days, 315 (1960).

Prior to February 1960, lunch counters throughout the South

denied normal service to Negroes. Six months later, lunch counters

in 69 cities had ended their discriminatory practices (N. Y. Times,

Aug. 11, 1960, p. 14, col. 5). By September 1961, desegregation

had occurred in business establishments located in more than 100

cities in fourteen states (The Student Protest Movement: A Re

capitulation, Southern Regional Council, Sept. 1961); and since

then the number has continued to increase without apparent inci

dent.

8

vinced and arranged for them to remain on the premises

presumably for an indefinite period of time” (R. 44).

(Emphasis added.)

The Alabama Court then rationalized that, “ There is a

great deal of analogy to the sit-down strikes in the auto

mobile industry referred to in National Labor Relations

Board v. Fansteel Metallurgical Corp., 306 U. S. 240”

(R. 44). This may very well be true, but this record is

devoid of any proof of the analogy. There is not a scintilla

of evidence in this record that petitioners urged, suggested,

or intended the sit-in demonstrators engage in any unlawful

conduct. What petitioners in fact urged is simply and

plainly not shown by this record. All the record shows as

to petitioner Billups is that he drove one of the students

to Rev. Shuttlesworth’s home and was present during the

discussion. For all that the record shows, this petitioner

remained silent.

Sit-down demonstrations have taken many forms.4 And

many of these convictions have been reversed as not having

been evidence of a crime. See Garner v. Louisiana, 368

U. S. 157; see Pollitt, op. cit. supra, at p. 350 (trespass

convictions of students convicted in Raleigh, N. C. dis

missed) ; King v. City of Montgomery,------ A la .------ , 128

So. 2d 341 (trespass convictions for sit-in in private hotel

reversed); Briscoe v. State of Texas, 341 S. W. 2d 432;

Rucker v. State of Texas, 341 So. 2d 434; Tucker v. State

of Texas, 341 So. 2d 433; Johnson v. State of Texas, 341

So. 2d 434 (convictions of sit-ins for unlawful assembly

reversed). Moreover, the students who sought service at

the lunch counters in the Birmingham cases before this

Court for review did not violate any valid ordinance by

peacefully seeking such food service since the Birmingham

Ibid.

9

ordinance requiring racial segregation in restaurants or

other places serving food is unconstitutional on its face.5

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U. S. 350.

The due process criterion applied by this Court in Garner,

supra, and Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199,

must be invoked here to void these convictions on records

barren of evidence.

B. This Record Discloses Only an Exercise of Constitutionally

Protected Freedom of Assembly and Speech.

Protest demonstrations against racial discrimination in

places of public accommodation in the United States ante

date by almost a century the current wave of Negro student

“ sit-in” or “ sit-down” demonstrations which commenced in

Greensboro, North Carolina on February 1, I960.6

The more recent Negro student sit-in demonstrations

have been viewed from their inception as the exercise of

5 “ ‘Sec. 369. Separation of Races.

It shall be unlawful to conduct a restaurant or other place

for serving of food in the city, at which white and colored peo

ple are served in the same room, unless such white and colored

persons are effectually separated by a solid partition extending

from the floor upward to a distance of seven feet or higher,

and unless a separate entrance from the street is provided for

each compartment’ ” (1930, §5288).

This ordinance is judicially noticeable by the Alabama courts,

Ala. Code Ann. Tit. 7, §429 (1) (1940). See Shell Oil v. Edwards,

263 Ala. 4, 9, 81 So. 2d 535, 539 (1955) ; Smiley v. City of Bir

mingham, 255 Ala. 604, 605, 52 So. 2d 710, 711 (1951). “ ‘The act

approved June 18, 1943, requires that all courts of the State take

judicial knowledge of the ordinances of the City of Birmingham.’ ”

Monk v. Birmingham, 87 F. Supp. 538 (N. D, Ala. 1949), aff’d

185 F. 2d 859, cert, denied 341 U. S. 940. And this Court takes

judicial notice of laws which the highest court of a state may

notice. Junction B.B. Co. v. Ashland Bank, 12 Wall. (U. S.) 226,

230; Ahie State Bank v. Bryan, 282 U. S. 765, 777, 778; Adams v.

Saenger, 303 U. S. 59; Owings v. Hull, 9 Peters (U. S.) 607, 625.

6 Westin, “Bide-In,” American Heritage, Vol. XIII, No. 5, p.

57 (1962).

10

constitutionally guaranteed free speech under at least some

circumstances. Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157. (Con

curring Opinion of Mr. Justice Harlan.) They are, by their

inherent and manifest nature, a protest against racial

discrimination.7

The record here discloses only that these petitioners met

with Negro students shortly after these protests began on

February 1, 1960 and discussed these demonstrations. The

sole witness in this case testified that he heard one of the

students testify that “ . . . the meeting was in the living

room of Reverend Shuttlesworth’s house and that Reverend

Shuttlesworth participated in the discussion about the sit-

down demonstrations” (R. 28). Petitioner Shuttlesworth

asked for “volunteers” to participate in a “ sit-in” or “ sit-

down” demonstration. At one point, petitioner Shuttles

worth told one of the students that he would get him out

of jail. Beyond this, there is no evidence in this record

concerning precisely the activities petitioners are supposed

to have counseled and no evidence concerning the “ sit-in”

or “ sit-down” demonstrations themselves which followed

this counsel.

The Birmingham city ordinance requiring racial segrega

tion in public restaurants makes clear that the City’s policy

was one of racial segregation in this area and that the sit-in

demonstrations here as in other communities across the

South were designed as a protest against this state policy.

The due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

guarantees the right to make a peaceful protest against

state enforced racial segregation. NAACP v. Alabama, 357

U. S. 449. The evidence in the students’ cases before this

Court is uncontradicted that the students were at all times

7 Note, Lunch Counter Demonstrations; State Action and the

Fourteenth Amendment, 47 Virginia Law Review 105.

11

peaceful. At the very least, the constitutional protection ex

tends to a discussion in a private home of sit-ins, especially

where it is not demonstrated that any unlawful action was

discussed or, in fact, taken.

To sustain these convictions would license Alabama to

invade the privacy and freedom of every home where anti-

discrimination discussions take place. Mr. Justice Brandeis’

admonition in his dissenting opinion in Gilbert v. Minnesota,

254 U. S. 325, where this Court had upheld, against a sim

ilar free speech consideration, a statute proscribing the

teaching of pacifism is particularly applicable here. Justice

Brandeis warned that the statute there made it a crime

“ to teach in any place a single person that a citizen should

not aid in carrying on a war, no matter what the relation

of the parties may be. Thus the statute invades the privacy

and freedom of the home. Father and mother may not fol

low the promptings of religious belief, of conscience or of

conviction, and teach son or daughter the doctrine of paci

fism. If they do any police officer may summarily arrest

them” (at pp. 335-336).

Petitioners here need not claim an absolute immunity

from state regulation of their free speech activities, but

they claim that their discussions on the night of March 30,

1960, are protected against the punishment which the state

here seeks to impose, since there has been no showing that

their discussion was “ . . . likely to produce a clear and

present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far

above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest.” Ter-

nvinietto v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, 4. Petitioners are not

charged with having conducted a meeting in an unlawful

manner, e.g., by sound truck, Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77

or without a permit where one was required, Cox v. New

Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569, or under circumstances dangerous

to public safety, e.g., Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315,

12

but cf. Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, or to

have spoken or met in a manner otherwise illegal. Neither

have they been punished for crime for having created a

clear and present danger of a substantive evil which the

state has the power to prevent. Cf. SchencJc v. United

States, 249 U. S. 47.

The Court of Appeals of Alabama rested its free speech

restriction in this case upon the fact that petitioner Shut-

tlesworth had promised to get the students out of jail;

but, as pointed out above, there is no evidence in this

record at all that Shuttlesworth requested any one to

perform an unlawful act. Many of the sit-in demonstrators

have been arrested and their convictions have been re

versed. And, as this Court ruled in the Garner case supra,

such demonstrations are not necessarily a crime.

The convictions of these petitioners under the facts of

this case are so clearly repugnant to our common notions

of rights protected by the constitutional guarantees of

freedom of assembly and speech as to require reversal by

this Court.

C. The Ordinance for Violation of Which Petitioners

Were Convicted Is Constitutionally Vulnerable on

the Grounds of Vagueness.

Petitioners were convicted of inciting students to violate

the trespass after warning ordinance of the City of Bir

mingham. This ordinance, which provides that, “ It shall

be unlawful for any person to incite, or aid or abet in, the

violation of any law or ordinance of the City, or any pro

vision of state law the violation of which is a misdemeanor”,

is constitutionally vague.

The record here shows that these petitioners did no more

than discuss sit-in demonstrations and offer to assist those

who volunteered for such demonstrations if they should

13

become embroiled with the law. The ordinance which con

victs them clearly did not give fair warning that to discuss

such a sit-in protest is a crime. Indeed, as observed, supra,

often the demonstrations have resulted in desegregation;

when criminal prosecution has ensued, frequently it has

failed.

This Court has repeatedly held that a criminal statute

or ordinance of this kind must give fair warning to a defen

dant of what acts are prohibited, Connally v. General Con

struction Co., 269 U. S. 385; and where, as in this case, free

speech encroachments are involved, the statute must be

even more specific. Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507;

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495; Saia v. New York, 334

U. S. 558; Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568.

Consequently, where the law has given no notice that lawful

free speech may be criminal, these convictions cannot be

sustained.

CONCLUSION

For all the foregoing reasons, the petitioners’ convic

tions by the Alabama courts must be reversed.

C onstance B aker M otley

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

A rth u r D. S hores

P eter A . H all

O rzell B illingsley , J r .

Oscar W . A dams, J r .

J. R ichmond P earson

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioners

L eroy D . Clark

of Counsel