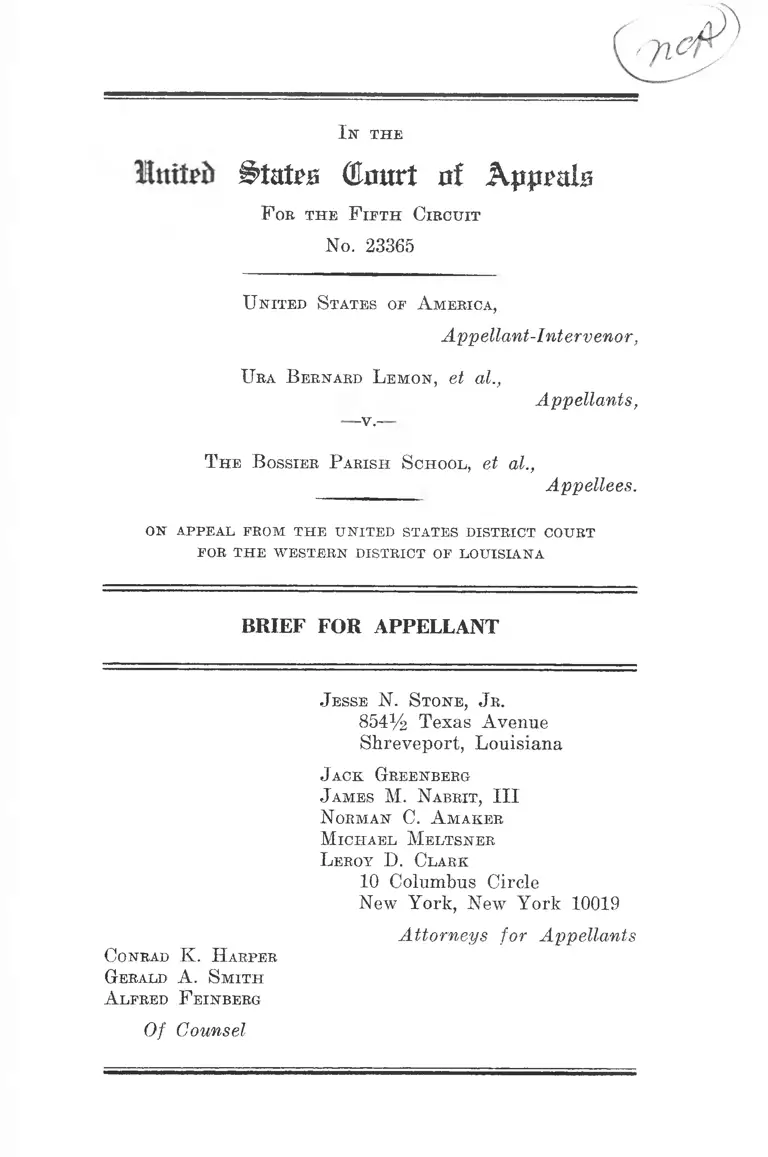

United States v. The Bossier Parish School Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

April 23, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. The Bossier Parish School Brief for Appellant, 1966. 0067404b-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/97da4ef4-99b9-4d6d-9eb5-e6614f863870/united-states-v-the-bossier-parish-school-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

t̂afejs (daurt af Appî als

F ob the F ifth Ciecuit

No. 23365

U nited S tates of A mebica,

AppellanUlntervenor,

U ea B ebnaed Lemon, et al.,

Appellants,

-V .-

The B ossieb P akish S chool, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FEOM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOB THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Conrad K. H aepeb

Gerald A. S mith

A lfred F einbeeg

Of Counsel

J esse N. S tone, J b .

854% Texas Avenue

Shreveport, Louisiana

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abbit, III

N orman C. A maker

Michael Meltsneb

Leroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement ........................................................................ 1

The Present Method of Initial Assignment .......... 5

Teacher and Staff Segregation .......................... 6

School Transportation ........ —............. .................. 6

Unequal Negro Schools ........................................... 7

Specifications of Error ................... 9

A r g u m e n t :

I. The Bossier Parish Plan Ordered by the Dis

trict Court Palls Short of This Court’s

Standards With Regard Both to Pupil and

Staff Desegregation ....................................... 11

II. The Inferiority of Negro Schools (1) Entitles

Negro Students to a Right of Immediate

Transfer in All Grades and (2) Requires the

School Board to Devise a Plan Which Max

imizes Desegregation ....................................... 22

Conclusion...................................................................... 25

Certificate of Service ....................... ........... ................... 27

Appendix ..................... la

Table op Cases:

Beckett v. School Board of Norfolk, Civ. No. 2214

(E.D. Va.) ............. ........................... ...... ..................18,19

Boson V. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) ............. . 15

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103 ....11,15

11

PAGE

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

Civ. No. 3353 (E.D. Va., March 30, 1966) ................. 19

Brooks V. County School Board of Arlington, Virginia,

324 F.2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963) ....................................... 15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....14, 22

Carr, et al. v. Montgomery Board of Education, Civ.

No. 2072-N (N.D. Ala., March 22, 1966) .................. 25

Dove V. Parham, 282 E.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) .......... 15

Dowell V. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 244 E. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) ...... 16,17,

19, 21, 22

Goss V. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 ................. 15,19

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U.S. 218 ............................................... 15

Houston Independent School District v. Ross, 282 E.2d

95 (5th Cir. 1960) ...................................................... 15

Kemp V. Beasley, 352 P.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) .......... 21

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County,

249 F.2d 239 (W.D. Va. 1966) ......................16,17,19, 22

Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) 22

Price V. Denison Independent School District, 348 F.2d

1010 (5th Cir. 1965) ........................................... 2, 4,11, 21

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198....................................... 12, 22

Ross V. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1963) ................. 15

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ............. .11,12,14,15

Ill

PAGE

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) .............. 1,2,4,14,21

Sipuel V. Board of Regents, 332 TJ.S. 631 (1948) .......... 22

Sweat! v. Painter, 339 TJ.S. 629 (1950) ........... ............. 22

Statutes:

Title VI, Civil Eights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C.A.

2000d) .......................................................................... 20

Other Authorities:

§181.13 Revised Statement of Policies for School

Desegregation (1966), Office of Education, Depart

ment of Health, Education and Welfare ................16, 20

§181.15 Revised Statement of Policies for School

Desegregation (1966), Office of Education, Depart

ment of Health, Education, and Welfare ................. 25

I n the

IkixUh tomrt of Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 23365

U nited S tates of A merica,

Appellant-Intervenor,

U ra B ernard Lemon, et al.,

----V.—

The B ossier P arish S chool, et al.,

Appellants,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OP LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement

This is an appeal from the August 20, 1965, decree

(R. Vol. II, 261-263), as clarified August 23, 1965 (Ap

pendix, infra, la)^ of the court below purporting to

adequately amend and modify a school desegregation plan

adopted by the district court on July 28, 1965 (R. Vol. II,

251-258). The modifications of the district court were pur

suant to an order of remand from this Court (R. Vol. II,

260-261) to reconsider the July 28, 1965, order in the light

of Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis-

̂Original order filed in the district court, August 23, 1965.

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5tli Cir. 1965), and Price v. Denison

Independent School District, 348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965).

On December 2, 1964, plaintiffs, Negro parents and their

children residing at Barksdale Air Force Base in Bossier

Parish, Louisiana, filed a complaint in the United States

District Court for the Western District of Louisiana seek

ing an injunction requiring* appellees. The Bossier Parish

School Board, and its Superintendent, Emmett Cope, to

desegregate the school system (E. Vol. 1 ,1-12). The United

States filed a Motion to Intervene on January 4, 1965

(R. Vol. I, 19-20).

Subesquently, plaintiffs and intervenor filed Motions

for Summary Judgment (R. Vol. I, 62, 65). On April 13,

1965, the district court entered an order granting the

government’s Motion to Intervene and granting plaintiffs’

and intervenor’s Motions for Summary Judgment (R. Vol.

I, 100-113). At that time the court further ordered the

appellees to submit a plan for desegregation (R. Vol. I,

113-116). The school board appealed from that order

(R. Vol. I, 125). That appeal is presently pending before

this Court. On July 28, 1965, the court adopted a some

what modified plan (R. Vol. II, 251-258) submitted by the

school board (R. Vol. II, 2-12). Plaintiffs and intervenor

objected to the plan as modified. That plan provided

for free transfer privileges for the school year 1965-66

for pupils in the first and twelfth grades to the first or

twelfth grade of any school of their choice within the

Bossier Parish School Board jurisdiction (R. Vol. II, 252).

All other grades were to remain totally segregated. The

free transfer privilege was superimposed on the already

existing system of initial student assignment based on race.

“All initial pupil assignments made for the school year

1965 through 1966 . . . [were] . . . considered adequate

. . (E. Vol. II, 251).

Twelfth grade pupils were to be advised by mail of their

right to transfer and of procedures attendant thereto.

Notification of pupils in the first grade was to be given

by publication in the Shreveport Times for a period of

three (3) consecutive days (R. Vol. II, 252). Requests

for transfers were not to be unreasonably denied hut were

to be considered in light of the desire of the parents, the

availability of space in the requested school, the age of

the transferring pupil compared to the age of pupils in

the chosen school, and the availability of requested courses

(R. Vol. II, 253-255). As a further condition, an applicant

could be assigned to a “comparable school closest to the

pupil’s residence rather than to the school to which the

transfer or assignment was requested” (R. Vol. II, 254).

While the order specifically provided that applications

for transfer from the twelfth and first grades must be

made between August 9 and 12, 1965, and August 16 and

20, 1965, respectively, it also provided that transfers

would be made in accordance with current transfer pro

cedures (R. Vol. II, 252-253). These procedures permit

applications to be made within fifteen (15) days from the

date of official assignment with certain exceptions for

hardship cases (R. Vol. I, 59). Students entering the sys

tem for the first time, regardless of grade, were to be

accorded their choice of school, Negro or white, closest

to their home (R. Vol. II, 255).

A different plan for desegregating the first, second,

eleventh and twelfth grades in the school year 1966-67

was contemplated. Desegregation of all grades under this

plan was to be completed by September 1968 (R. Vol. II,

256). The desegregation plan for 1966 through 1968 pro

vided that school assignments were to be made “purely

and simply on the basis of individual choice,” however,

the above described transfer provisions were to be re

tained as well as the right of the school board to assign

an applicant to “a comparable school closer to the pupil’s

residence than is the school of Ms choice” (R. Vol. II, 256).

It was further provided that the system of dual zones

was to be abolished contemporaneously with the progress

of grade desegregation (R. Vol. II, 256).

On August 5, 1965, appellant-intervenor appealed the

order of July 28, 1965, which approved the school board’s

plan (R. Vol. II, 258). On August 17, 1965, this Court

vacated the July 28th order and remanded to the district

court for consideration in the light of Singleton and Price,

supra.

Pursuant to the order of remand, the district court, on

August 20, 1965, issued an order limiting the modification

of its decree solely to increasing the rate of annual de

segregation so that all grades would be under the desegre

gation plan by the fall of 1967 (R. Vol. II, 261-263).

Notification of the newly included grades 2 and 11 for

1965 w'as to be by a three (3) day newspaper advertise

ment. “Otherwise, all the terms and conditions of the

original order of July 28, 1965 . . . [were] . . . reinstated

. . . [to] . . . remain in full force and effect” (R. Vol. II,

262). On August 23, 1965, the district court further

clarified the August 20th order by denying the motion

of the nominal plaintiffs to attend a formerly all-white

school, notwithstanding the fact that the desegregation

plan had not as yet reached their grades (Appendix la).

Under the orders of the court below the following de

segregation has occurred: Bossier Parish school system

consists of 23 schools and about 4,400 Negro students and

11,000 whites (E. Vol. I, 45). The system is divided into

six (6) school districts (R. Vol. II, 48) ̂ and serves all

children residing in Bossier Parish (R. Vol. II, 66). Pres

ently only 31 Negro pupils are enrolled in formerly all-

white schools.®

The Present M ethod of Initial Assignm ent

Except as qualified by the free choice plan to go into

effect in the years subsequent to the 1965-66 school year,

initial assignment of pupils in Bossier Parish schools con

tinues, as in the past, to be based on race. Students are

segregated on the basis of dual attendance zones (R. Vol.

II, 43-45, 75). Mr. Cope, the School Superintendent, con

cedes that a redrawing of attendance areas based upon

residence rather than upon race would result in “a possi

bility” that white students who presently attend distant

schools would go to schools closer to their homes (R. Vol.

II, 78). Indeed, he admits that maintaining a dual school

system has created substantial administrative problems (R.

Vol. II, 76). Testimony by Mr. Cope indicates that the

desegregation plan, at least as originally conceived, does

̂Bossier Parish is divided into taxing districts used as a rough esti

mate of attendance areas for schools contained therein (E. Vol. II, 45-50,

52, 110-111). However, theoretic legal restrictions imposed by district

lines (R. Vol. II, 54-55) do not in fact limit the discretion of the board

in the initial assignment of pupils to schools within the Parish (E. Vol

II, 61, 73-74, 109-110).

Consolidation of school districts has resulted in the present distribution

of school Districts 1, 2, 3, 13, 26 and 27 of the original 27 districts (R.

Vol. II, 45-49).

2 Afhdavit of St. John Barrett, attached to the Motion to Consolidate

and Expedite Appeals (Nos. 23173, 23192, 23274, 23331, 23335, 23345

and 23365) filed by the United States in this Court April 4, 1966.

not contemplate any change in the method of initial assign

ment even in those grades reached by the plan.^

Teacher and Staff Segregation

Notwithstanding that Negro and white teachers are com

parably qualified to teach in the Bossier Parish School

System (E. Vol. II, 85-87) teaching staffs remain completely

segregated (R. Vol. II, 179). While it is true that three

years of service gives a teacher tenure providing a certain

amount of protection against an undesired transfer to

another school, of the some seven hundred (700) teachers

in the school system, two hundred (200) to two hundred

and fifty (250) have either not been employed for three

years or have just come into the ŝ ŝtem. These teachers

have no legal option to determine where they will be as

signed to teach (R. Vol. II, 175-178). Negi’o and white

supervisory personnel not only have different jurisdictions,

they also are segregated from each other; thus white per

sonnel work at the central office in Benton and Negro

personnel are located at Butler Elementary School in Bos

sier City (R. Vol. I, 51).

School Transportation

Negro and white children in Bossier Parish are trans

ported separately to their respective schools (R. Vol. I,

52). There are only six (6) Negro schools out of a total of

twenty-three (23) schools (R. Vol. I, 45-46) and only about

Q. How does this plan change the method of assignment currently

existing under the dual system? A. Maybe I can answer the question by

this method; From May 1 to May 15 every student we have in the Bossier

Parish School System is assigned to the particular school which he attends.

Q. In the ease of a Negro student it is a Negro school and in the ease

of a white student it is a white school? A. Yes.

Q. Isn't that the system you are operating under now? A. Yes. (R.

Vol. II, 88-89.)

4,000 Negro pupils out of a total of nearly 15,000 (E. Vol. I,

45), yet forty-one (41) buses are needed to transport Negro

children and fifty-two (52) buses are required for white

children (R. Vol. I, 52). Although testimony in the record

indicates that buses going to formerly all-white schools

would carry Negroes who had integrated into those schools

(E. Vol. II, 101), the integration of buses is neither offered

by appellees’ desegregation plan (R. Vol. II, 101), nor

incorporated by the district court in its desegregation order

(R. Vol. II, 251-258).

Unequal ISegro Schools

The schools operated for white and Negro children in

Bossier Parish show considerable disparity in a number

of qualitative aspects. The white high school (Bossier)

for one district offers 53% courses over a four year period,

including two years of Latin, two years of French, two

years of Spanish, and three years of art (R. Vol. II, 184-

185). However, the Negro high school (Stikes) for the

same district offers only 28 courses, and offers no Latin,

French, or Spanish (E. Vol. II, 186). Another district’s

white high school (Airline) offers 43.5 courses, while the

Negro high school (Mitchell) offers 30.5 (R. Vol. II, 189).

Similarly, the white high school (Haughton) for a third

district offers 40.5 courses, while the Negro high school

(Princeton) offers 34 (R. Vol. II, 192). The Superintend

ent stated that the criterion for offering a course was:

if a course is requested on the senior high level by

as many as ten students we attempt to offer that course

in that particular school. Yet, at the same time, there

are other factors where maybe ten students have not

applied as far as conditions are concerned in the other

schools and I think that situation has to be taken into

consideration (R. Vol. II, 100).

8

Disparities are found in other respects in addition to the

number of course offerings. While there are two full time

guidance counselors at Airline (white), there are none at

Mitchell (Negro) (R. Vol. II, 190). In fact, while there

generally are guidance counselors at the schools for whites

in the parish, there are none at any of the Negro schools

(R. Vol. II, 187, 194). At the Princeton school (Negro),

there are 3.8 volumes of “approved books in good condi

tion” per pupil, while at Haughton (white) in the same

district there are 6.3 per pupil (R. Vol. II, 190-191).

At the hearing on the objections to the plan, Mr. William

Stormer, Specialist, School Housing Statistics, United

States Office of Education, Department of Health, Educa

tion, and Welfare, an expert in the evaluation of the qual

ity of school plants, testified on his findings during an

inspection of the Bossier Parish schools in the summer of

1965 (R. Vol. II, 195-198). Using the Lynn-McCormick

Rating System developed at Teachers College of Columbia

University which combines a number of weighted ratings

of different aspects into an overall rating which allows

numerical comparisons between schools, he determined

that the highest white school (Airline) ranked at 82 on the

scale, while the highest Negro school (Mitchell) ranked

at 16 (R. Vol. II, 199, 202). Fifteen of the seventeen white

schools rated above the first Negro school (R. Vol. II, 202).

When challenged upon cross-examination that there was

really no dramatic difference between the Negro and white

schools, he responded: “Yes, there is. I beg your pardon.

For example, the Avooden structures used at Stikes for

what I presume to be elementary classrooms . . . there are

no wooden structures at Curtis” (R. Vol. II, 209). Simi

larly, the structures used for elementary grades at Irion

(Negro) are wooden, while those used for the same purpose

at Benton (white) are not (R. Vol. II, 209). The home

economics facilities at Stikes high school (Negro) are in

a wooden frame two story structure, whereas similar

facilities at Bossier high school (white) are in a modern

main building (R. Vol. II, 200). All of the Negro schools

must use their gymnasiums as auditoriums, while Airline,

Bossier, Benton, and Haughton schools which are all white

have separate auditorium facilities (R. Vol. II, 200-201).

The gymnasium floors in all of the Negro high schools are

constructed of cement or asphalt tile surface, compared to

wooden floors in all of the vdiite high schools (E. Vol. II,

200).

Specifications o f E rro r

The district court erred in;

1. Refusing to find that the Bossier Parish School

Board, having established and maintained a racially segre

gated school system, is constitutionally obligated to submit

a desegregation plan which, in fact, completely disestab

lishes segregated patterns and eradicates Negro and white

schools.

2. Approving the so-called free choice provisions con

tained in the district court’s desegregation plan over ob

jections that such provisions failed to disestablish racial

segregation and despite undisputable evidence that:

a. Approval of the plan retains virtually intact Negro

and white schools;

b. The alleged free choice provisions are in reality a

transfer scheme perpetuating dual zone lines;

c. The plan fails to permit students attending inferior

schools, whether in the segregated or desegregated grades,

10

to transfer to schools from which they have been excluded

because of race;

d. The plan fails to provide for desegregation of facili

ties such as bus transportation;

e. The plan fails to provide notice of its provisions

other than in a newspaper of general circulation for the

years subsequent to the 1965-66 school year;

f. The plan fails to provide for the upgrading of Negro

schools so as to make transfers a realistic consideration

for all pupils;

g. The plan fails to provide for alternative assignment

criteria where facts reveal that it would lead to significant

desegregation.

3. Approving a gradual so-called free choice desegrega

tion plan despite the absence of valid administrative fac

tors justifying such delay and despite the fact that Negro

educational facilities are clearly inferior.

4. Refusing to find that staff desegregation is a pre

requisite for effective school desegregation requiring the

immediate submission of a specific plan providing for both

(a) nonracial hiring and assignment of staff personnel to

effect desegregation, and (b) assignment of staff personnel

based on race in order to correct the past effects of segrega

tion and discrimination.

11

ARGUMENT

I.

T he B ossier P a rish P lan O rd ered by th e D istric t C ourt

Falls S hort o f T his C ourt’s S tandards W ith R egard B oth

to P u p il and Staff D esegregation.

In Price v. Denison Independent School District, 348

F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965), this Court adopted the United

States Office of Education’s Statement of Policies for

School Desegregation under Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (April 1965) as its minimum desegregation

standards. In March 1966, a Revised Statement of Policies

for School Desegregation was issued, which revised state

ment is no less appropriate to current school desegrega

tion questions than was the statement issued in April 1965.

See, Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103

and Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 P.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966).

The minimum standards for school desegregation plans

were set out in extenso in Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, 355 F.2d 865, 870-871 (5th Cir.

1966). Those standards briefly are as follows:

1. All grades must be desegregated by September 1967;

2. Individuals in segregated grades are permitted to

transfer to schools from which they were originally ex

cluded or would have been excluded because of their race;

3. Services, programs and activities, including buses,

shall be available without discrimination on the basis of

race;

12

4. An adequate start must be made toward elimination

of race as a basis for staff employment so that school

systems will be totally desegregated by September 1967;

5. Proper notice, including use of newspapers, radio

and television facilities, must be given to children and their

parents of the desegregation plan;

6. Dual geographic zones must be abolished as a basis

for assignment;

7. Additional choices of schools must be made available

where the first choice is unavailable.

The Bossier plan fails to meet these criteria. Although

it provides for complete pupil desegregation by Septem

ber, 1967, the plan has no provision permitting individuals

in segregated grades to transfer to schools from which

they were originally excluded or would have been excluded

because of their race. Thus the plan, in this regard, is not

only deficient under the criteria of the second Singleton

decision, but also under Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198. The

plan makes no provision for the desegregation of services,

programs, and activities, such as bus transportation.

The plan fails to provide for proper notice of the plan’s

contents to children and parents. The second Singleton

decision found notice adequate where radio and television

facilities were used in addition to newspaper announce

ments. The Bossier Parish plan provides for notification

to twelfth grade pupils by mail but merely provides for

three newspaper announcements to pupils in grades two,

eleven, and those entering grade one in the fall of 1965.

The plan also provides that applications for transfer from

the twelfth and first graders must be made between August

9 and 12, 1965 and August 16 and 20, 1965, respectively.

13

Transfers for the 1965-66 school year were subject to

“current” transfer procedures, i.e., applications could gen

erally be made within fifteen days from the date of official

assignment to a particular school. In short, parents seek

ing to obtain transfers for their children for the fall of

1965 were, except for the twelfth-grade students, forced to

rely upon a three-day newspaper announcement and a com

parably short period of time for filing applications. What

ever the defects of the fall 1965 procedure may be, they

are slight in view of the complexity and obscurity of the

plan’s notice provisions regarding the school years 1966-67

and 1967-68.

The plan grandly declared that school assignments from

1966 through 1968 were to be made “purely and simply

upon the basis of individual choice” and that dual racial

zones are to be abolished contemporaneously with the

progress of grade desegregation. Nonetheless, for the

school years subsequent to 1965-66, the plan provides no

procedures whereby the alleged free choice option is to be

processed and provides no indication that any publicity

will be given to the fact that freedom of choice is possible.

Furthermore, students, in accordance Avith the usual school

board procedures,^ will be assigned on a racial basis to

their respective schools betAveen May 1 and May 15 of 1966

and 1967.

Incontrovertibl}', therefore, the plan at best envisions an

unpublicized transfer procedure from an initial racial as

signment masquerading as “pure” free choice.

The plan fails to specify that additional choices of schools

are available where pupils’ first choices are not. Indeed,

5 The court-ordered plan was quite explicit in providing that “All

initial pupil assignments [based on race] made for the school year 1965

through 1966 . . . [are] . , . considered adequate . . . ” (R. Vol. II, 251).

14

the plan specifically provides that a pupil’s request to

transfer is subject to the school board’s discretion to assign

the applicant to a “comparable school” closer to the stu

dent’s residence than the student’s chosen school. Thus the

plan, rather than seeking to give its transfer provisions

wide latitude by vesting discretion in the student applicant,

affirmatively looks toward school board actions which might

well perpetuate segregation by pupil assignment. Such

perpetuation would, of course, insure the immortality of

dual zoning. This Court has now clearly held that school

boards operating a dual system are constitutionally re

quired not merely to eliminate the formal application of

racial criteria to school administration, but must also by

affirmative action seek the complete disestablishment of

segregation in the public schools. Singleton v. Jackson

Micnicipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir.

196o), 3o5 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966). As succinctly stated

in the first Singleton opinion, “ . . . the second Brown

decision clearly imposes on public school authorities the

duty to provide an integrated school system.” 348 F 2d at

730, n. 5.

The Bossiei Parish plan does not effectively desegregate

its pupil population. Presently, only thirty-one Negro

pupils are enrolled in formerly all-white schools in the

school system which has nearly 15,000 pupils, of whom

some 4,000 are Negroes.® The record reveals that many

of the board’s assignment policies have as their sole justi

fication the perpetuation of segregation. Thus, for example,

Negro children residing in District No. 26, where

the only school is one for whites, attend school in other

Districts where Negro schools are located (R. Vol. II, 51-

® Affidavit of St. John Barrett, attached to the Motion to Consolidate

and Expedite Appeals (in Nos. 23173, 23192, 23274, 23331, 23335, 23345

and 23365) filed by the United States in this Court April 4, 1966.

15

52, 109-110). The School Siipermtendent frankly admitted

that dual zoning was an administratively difficult proce

dure (E, Vol. II, 76). These facts demonstrate that the

so-called freedom of choice plan has not worked and that

either extensive revision of it is needed, or another method

of desegregation should be adopted, e.g., assignment on

the basis of race to effect desegregation, unitary non-racial

geographic zoning. This Court and other courts have fre

quently held that if the application of educational prin

ciples and theories results in the preservation of an existing

system of imposed segregation, the necessity of vindicat

ing constitutional rights will prevent their use. Ross v.

Dyer, 312 F.2d 191, 196 (5th Gir. 1963); Dove v. Parham,

282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. I960); Brooks v. County School

Board of Arlington, Virginia, 324 F.2d 303, 308 (4th Cir

1963).

The district court’s desegregation order reflects its fail

ure to grasp the considered principle that schemes which

technically approve desegregation but retain the school

s3̂ stem in its dual form must be struck down. Goss v.

Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683; Griffin v. County School

Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218; Boson v.

Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (oth Cir. 1960); Houston Independent

School District v. Ross, 282 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1960).

B.

The district court’s order failed to require desegregation

of staff personnel and is therefore in conflict with the

settled rule that desegregation plans must make an ade

quate start toward the elimination of teacher and other

staff segregation. Bradley v. School Board of Richmond,

382 U.S. 103; Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 355 F.2d 865, 870 (5th Cir. 1966).

16

Prompt faculty desegregation is also required by revised

school desegregation guidelines, issued by the United States.

Office of Education, which make each school system respon

sible for correcting the effects of all past discriminatory

teacher assignment practices and call for “significant prog

ress” toward teacher desegregation in the 1966-67 school

year. Thus, new assignments must be made on a nonracial

basis “ . . . except to correct the effects of past discrim

inatory assignments.” Revised Statement of Policies for

School Desegregation (March 1966), §181.13(b). The pat

tern of past assignments must be altered so that schools

are not identifiable as intended for students of a particular

race and so that faculty of a particular race are not con

centrated in schools where students are all or prepon

derantly of that race. Id. at Sec. 181.13(d).

In view of the desired goal of desegregation, whether

by free choice or unitary geographic zoning, it is impera

tive that the Bossier Parish School Board be required

promptly to adopt effective faculty desegregation plans.

See Dowell v. School Board of Oklahovia City Public

Schools, 244 P. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), on appeal

to the 9th Circuit, No. 8523; and Kier v. County School

Board of Augusta County, 249 F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Va.

1966).

In the Oklahoma City case, the court, adopting the rec

ommendations of educational experts retained with the

court’s approval by plaintiffs to study the system and pre

pare an integration report, set a goal of 1970 by which

time there should be “ . . . the same approximate percentage

of nonwhite teachers in each school as there now is in the

system. . . . ” The 1970 date was keyed to personnel turn

over figures indicating that approximately 15% of the

total faculty is replaced each year, and to permit the ac-

17

complishment of faculty integregation by replacements to

the faculty as well as by transfers. 244 F. Supp. at 977-78.

In the Augusta County case, the district court noting the

small number of Negro teachers in the system, ordered

faculty desegregation to be completed by the 1966-67 school

term. Referring to the Oklahoma City case, supra, the

court said:

Insofar as possible, the percentage of Negro teachers

in each school in the system should approximate the

percentage of Negro teachers in the entire system for

the 1965-66 school session. Such a guideline can not

be rigorously adhered to, of course, but the existence

of some standard is necessary in order for the Court

to evaluate the sufficiency of the steps taken by the

school authorities pursuant to the Court’s order. 249

F. Supp. at 247.

The court acknowledged that the standard for teacher

assignments is race-conscious, but justified such relief as

necessary to correct discrimination practiced in the past.

Quoting from a 1963 opinion on the subject by the Attorney

General of California, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1303 (1963),

the court held that:

Clearly, defendants may consider race in disestab

lishing their segregated schools without violating the

Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. The

admonition of the first Mr. Justice Harlan in his dis

senting opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537,

559, 16 S.Ct. 1138, 41 L.Ed. 256 (1896) that ‘Our Con

stitution is color-blind’ was directed against the ‘sepa

rate but equal’ doctrine, and its rejection in Brown

V. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 6 8 6 , 98

L.Ed. 873, was an explicit recognition that separate

18

educational facilities are inherently unequal, and did

not convert Justice Harlan’s metaphor into constitu

tional dogma barring affirmative action to accomplish

the purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus,

racial classifications which effect invidious discrimina

tion are forbidden but may be upheld if deemed neces

sary to accomplish an overriding governmental pur

pose.

Recently, in Beckett v. School Board of Norfolk, Civ.

No. 2214 (E.D. Va.) where the faculty is 40% Negro, a

district court entered a consent order on March 17, 1966

approving a plan submitted by the Board containing pro

visions for teacher desegregation which in addition to

recognizing its obligation to take all reasonable steps to

eliminate existing racial segregation of faculty that has

resulted from the past operation of a dual school system

based upon race or color, committed the Board, inter alia,

to the following;

The Superintendent of Schools and his staff will take

affirmative steps to solicit and encourage teachers

presently employed in the System to accept transfers

to schools in which the majority of the faculty mem

bers are of a race different from that of the teacher

to be transferred. Such transfers will be made by

the Superintendent and his staff in all cases in which

the teachers are qualified and suitable, apart from

race or color, for the positions to which they are to

be transferred.

In filling faculty vacancies which occur prior to the

opening of each school year, presently employed

teachers of the race opposite the race that is in the

majority in the faculty at the school where the vacancy

exists at the time of the vacancy will be preferred in

19

filling such a vacancy. Any such vacancy will be

filled by a teacher whose race is the same as the race

of the majority on the faculty only if no qualified

and suitable teacher of the opposite race is available

for transfer from within the System.

Newly employed teachers will he assigned to schools

without regard to their race or color, provided, that

if there is more than one newly employed teacher who

is qualified and suitable for a particular position and

the race of one of these teachers is different from

the race of the majority of the teachers on the faculty

where the vacancy exists, such teacher will be assigned

to the vacancy in preference to one w-hose race is the

same.’

An effective faculty desegregation plan must establish

specific goals to be achieved by affirmative policies ad

ministered with regard to a definite time schedule. The

plans in the Oklahoma City, Augusta County and Norfolh

cases supra, meet these criteria. The Bossier Parish School

Board for valid constitutional and educational reasons

should be required to submit faculty desegregation plans

patterned after those in the Oklahoma City, and Augusta

County cases.

Faculty segregation impedes the progress of pupil de

segregation. Where, as here, students and parents are

given a choice of schools under the Bossier Parish plan,

faculty segregation influences a racially based choice. Ar

rangements which work to promote segregation and hamper

desegregation are not to be tolerated, Goss v. Board of

Education, 373 U.S. 683.

’ A similar plan was approved on March 30, 1966, by the district court

in Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, Civ. No. 3353 (E.D.

Va.) where about 50% of the teachers are Negro.

20

The United States Office of Education has noted the

negative consequences of pupil desegregation without con

current faculty desegregation. Thus, in further implement

ing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C.A.

2000d) the Office of Education in its March, 1966 Revised

Statement of Policies requires school districts submitting

plans for desegregation to comply with the following

policies:

§181.13 Faculty and Staff

(a) Desegregation of Staff. The racial composition

of the professional staff of a school system, and of

the schools in the system, must be considered in

determining whether students are subjected to dis

crimination in educational programs. Each school sys

tem is responsible for correcting the effects of all past

discriminatory practices in the assignment of teachers

and other professional staff.

(b) New Assignments. Race, color, or national

origin may not be a factor in the hiring or assign

ment to schools or within schools of teachers and

other professional staff, including student teachers and

staff serving two or more schools, except to correct the

effects of past discriminatory assignments.

(d) Past Assignments. The pattern of assignment

of teachers and other professional staff among the

various schools of a system may not be such that

schools are identifiable as intended for students of

a particular race, color, or national origin, or such

that teachers or other professional staff of a particular

race are concentrated in those schools where all, or

21

the majority, of the students are of that race. Each

school system has a positive duty to make staff as

signments and reassignments necessary to eliminate

past discriminatory assignment patterns. Staff de

segregation for the 1966-67 school year must include

significant progress beyond what was accomplished

for the 1965-66 school year in the desegregation of

teachers assigned to schools on a regular full-time

basis. Patterns of staff assignment to initiate staff

desegregation might include, for example: (1) Some

desegregation of professional staff in each school in

the system, (2) the assignment of a significant portion

of the professional staff of each race to particular

schools in the system where their race is a minority

and where special staff training programs are estab

lished to help with the process of staff desegregation,

(3) the assignment of a significant portion of the staff

on a desegregated basis to those schools in which the

student body is desegregated, (4) the reassignment

of the staff of schools being closed to other schools in

the system where their race is a minority, or (5) an

alternative pattern of assignment which will make

comparable progress in bringing about staff desegre

gation successfully.

These Office of Education standards for faculty desegre

gation are entitled to great weight. See Singleton v. Jack-

son Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729, 731

(5th Cir. 1965); Price v. Denison Independent School Dis

trict Board of Education, 348 F.2d 1010, 1013 (5th Cir.

1965); Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14, 18-19 (8th Cir. 1965).

Significantly, at least two district courts had fashioned

orders before the Office of Education adopted its Revised

Statement which complement the neAv regulations. Dowell

22

V. School Board of Oklahoma City Public Schools, 244 F.

Supp. 971, 977-78 (W.D. Okla. 1965) (appeal pending),

and Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County,

Virginia, 249 F. Supp. 239, 247 (W.D. Va. 1966), both

require plans under which the percentage of Negro teachers

assigned to each school would result in an equal distribu

tion of Negro teachers throughout the system. This or

similar relief is necessary to eliminate the problem of

faculty segregation in Bossier Parish. The School Board

should be required to submit an administrative plan for

faculty desegregation in accord with such definitive guide

lines.

II.

The Inferiority of Negro Schools (1 ) Entitles Negro

Students to a Right o f Immediate Transfer in All Grades

and (2 ) Requires the School Board to Devise a Plan

Which Maximizes Desegregation.

Well before Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954), it was clear that disparities in educational facilities

required immediate desegregation. Of. Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938), Sipuel v. Board of

Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948), Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S.

629 (1950). Recently in Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198, 199,

200 (1965), the Supreme Court held that pending the com

plete desegregation of Fort Smith, Arkansas, high schools,

Negro students enrolled at schools with less extensive cur

ricula were entitled to “immediate transfer to the high

school that has the most extensive curricula and from Avhich

they are excluded because of their race.”

In Bossier Parish, the Superintendent admitted the sub

stantially smaller number of course offerings at the Negro

23

high schools generally compared to the white high schools

(R. Vol. II, 184-194). It is submitted that the inequality

between Negro and Avhite high schools located in one dis

trict while dismissed by appellees as being caused by the

disparity in enrollment between the schools (R. Vol. II,

186) is, more fundamentally, the result of a decision to

maintain a segregated school system. Furthermore, simi

lar substantial disparities in course offerings are found

in districts in which enrollments in Negro and white high

schools are nearly identical (R. Vol. II, 191).

The Superintendent’s statement that the general rule

for determining whether to offer a course is receipt of

requests by ten students, but that there are “other factors”

which may cause a course to be offered even where ten

students have not so requested (R. Vol. II, 100) strongly

suggests that this “rule” is rigidly applied in Negro schools

to justify the lack of course offerings while generally

waived in white schools. In the latter schools, the board

apparently undertakes its educational responsibility to

stimulate the students by presenting a large variety of

course offerings on the theory that students may not be

aware that a course would be valuable if they don’t know

it exists, but feels no such similar responsibility in the

Negro schools.

The complete lack of guidance counselors in Negro high

schools compared to their presence at most white high

schools (R. Vol. II, 187-194) is a further illustration of

the general policy of the School Board to regard the

schools intended for Negroes as a separate and second

class school system with whose educational adequacy they

need be only minimally concerned. That this attitude un

derlies virtually all board policies is confirmed by the

extensive testimony offered by Mr. William Stormer, an

24

expert in evaluating school physical plants, that the physi

cal facilities of the Negro schools are generally quite

inferior to those of the white schools (E. Vol. II, 195-209).

The fact that fifteen of the seventeen white schools in the

parish ranked higher on the Columbia Teachers College

scale than the highest Negro school is eloquent testimony

to the situation of Negro students in Bossier Parish.

On the basis of the evidence, plaintiffs were clearly en

titled to a plan which included the right of immediate

transfer out of an inferior Negro school. The failure of

the district court to so order condemns Negro students in

the grades unaffected by the desegregation plan until 1967-

68 to at least another year at clearly inferior schools.

However, even if all students in the still segregated

grades were granted a right of immediate transfer, it is

probable that only token desegregation would occur. The

inferiority of Negro schools turns the desegregation process

approved in Bossier Parish into a one-way process. White

students could hardly be expected to abandon the superior

facilities and instructions available at white schools by

transferring to Negro schools. Thus, Negro students’ right

to transfer under the plan is circumscribed by the amount

of space available at white schools.

In recognizing the Negro students’ right not to be re

stricted to inferior schools, quite apart from their right

to a desegregated education, the Supreme Court clearly

intended school boards to devise plans which maximized

the extent of desegregation. Although a school board is

entitled to devise a desegregation plan which is geared to

the special circumstances of a particular school system, a

school board cannot select a desegregation process which

plainly restricts the amount of desegregation that will

occur.

25

Until Negro schools are brought up to par with white

schools and freedom of choice becomes meaningful to both

white and Negro students, a school board is obligated to

take further steps to maximize desegregation. Indeed,

just recently, unequal Negro schools were closed in three

Alabama counties to protect Negro students’ right to an

equal as well as a desegregated education. In Carr, et al.

V. Montgomery Board of Education, Civ. No. 2072-N (N.D.

Ala. March 22, 1966). Judge Johnson’s order further re

quired :

The Montgomery County Board will design and pro

vide remedial educational programs to eliminate the

effects of past discrimination, particularly, the results

of the unequal and inferior educational opportunities

which have been offered in the past to Negro students

in the Montgomery County School System.

Expansion of existing school plants to accommodate

displaced students will be designed to eliminate the

dual school system.

Similarly, the revised Health, Education and Welfare

school desegregation guidelines now require that “inade

quate” Negro schools be discontinued. §181.15, Eevised

Statement of Policies For School Desegregation Plans

Under Title VI of The Civil Eights Act of 1964.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated in this brief the desegregation

order entered by the lower court should be reversed and

the cause remanded with specific directions to the district

court to enter an order requiring the abolition of separate

zones, the establishment of unitary, geographic attendance

areas or other alternative assignment criteria which would

26

lead to significant desegregation, the desegregation of

faculty and professional staff, integrated bus transporta

tion, and the right of children in grades not yet reached

by the plan or children assigned to inferior schools to

transfer to schools from which they have been excluded

because of race.

Respectfully submitted.

Conrad K. H arper

Gerald A. S mith

A lfred F einberg

Of Counsel

J esse N. S tone, J r.

854% Texas Avenue

Shreveport, Louisiana

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A maker

Michael Meltsner

Leroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, blew York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

27

Certificate o f Service

This is to certify that I have this 23rd day of April,

1966 served one copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellants

upon each of the attorneys for the appellees and the United

States as listed below, by depositing true copies of same

in the United States mail, air mail, postage prepaid.

Hon. Jack P. F. Gremillion

Attorney General

State Capitol

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Hon. William P. Schuler

Assistant Attorney General

201 Trist Building

Arabi, Louisiana 70032

Hon. Louis H. Padgett, Jr.

District Attorney

Bossier Bank Building

Bossier City, Louisiana

Mr. J. Bennett Johnston, Jr.

Special Counsel for Defendants

930 Giddens Lane Building

Shreveport, Louisiana

Hon. John Doar

St. John Barrett

Peter Smith

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

Mr. Edward L. Shaheen

United States Attorney

Federal Building

Shreveport, Louisiana

Attorney for Appellants

la

APPENDIX

Ruling on Motion to Clarify and/or Amend

Previous Order and Decree

[CAPTIOK omitted]

Filed August 23, 1965

B en C. D awkins, J e., Chief Judge.

The named minor plaintiffs have sought to by-pass the

plan of desegregation entered and approved herein by

having the Court declare that they now" are entitled to

attend a formerly all-white school of their choice, even

though the over-all plan has not reached their grade level.

For this Court to rule to that effect w"ould be to give

an unfair advantage to the named minor plaintiffs over

the other members of the class they represent, something

which was never intended by the Court to be done, and

which we cannot do in good conscience even though the

parents of these children took the initiative in instituting

this suit. To do so would disrupt the orderly implementation

of the plan of desegregation, and we cannot allow this

to happen.

For these reasons, sitting as a court of equity of whom

evenhandedness is demanded, w"e must rule that the named

minor plaintiffs must await their turn, as all others in

their class must do, until their grade level is reached,

either in 1966 or 1967, as the case may be, before they

will be entitled to transfer to a formerly all-white school

of their choice.

Thus done and signed, in Chambers, at Shreveport,

Louisiana, on this 23rd day of August, 1965.

Chief Judge

M EILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C.