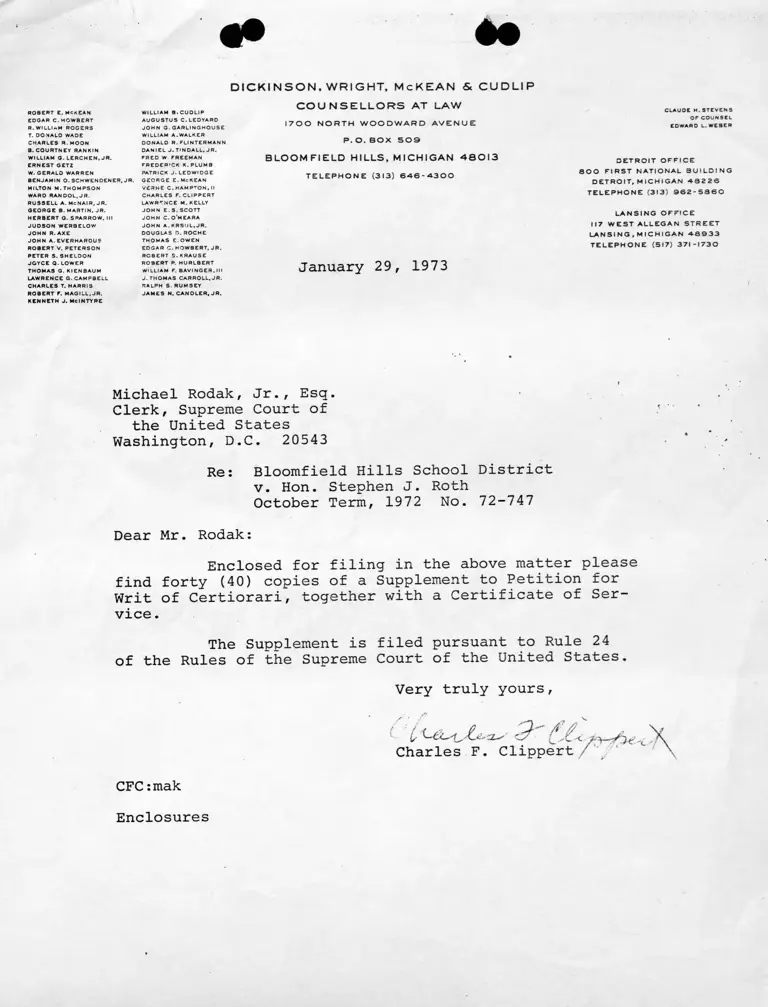

Letter from Clippert to Rodak RE: Supplement to Petition for Writ of Certiorari with Certificate of Service

Public Court Documents

January 29, 1973

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Letter from Clippert to Rodak RE: Supplement to Petition for Writ of Certiorari with Certificate of Service, 1973. 3424392c-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/98023ab7-f35d-49d6-b2dc-d2e60137e263/letter-from-clippert-to-rodak-re-supplement-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-with-certificate-of-service. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

«•

D I C K I N S O N , W R I G H T , M c K E A N & C U D L I P

R O B E R T E. MCKEAN

E D G A R C. H O W B E R T

R .W IL L IA M R O G E R S

T. O O N A L D WAD E

C H A R L E S R .M O O N

3. C O U R T N E Y RA N K IN

WILLIAM G. L E R C H E N , J R .

E R N E S T G E T Z

W . G E R A L D W A R R E N

B E N J A M IN O. S C H W E N D E N E R , J R .

M ILTO N M . T H O M P S O N

W AR D RAN DO L, J R .

R U S S E L L A. McNA IR , J R .

G E O R G E B. M A R TIN , J R .

H E R B E R T G. S P A R RO W , III

J U D S O N W E R B E L O W

J O H N R. A X E

J O H N A . E V E R H A R D U S

R O B E R T V. P E T E R S O N

P E T E R S. S H E L D O N

J O Y C E Q . LO W E R

T H O M A S G. Kl EN BAUM

L A W R E N C E G. C A M P B E L L

C H A R L E S T. H A R R IS

R O B E R T F. MAG ILL, J R .

K E N N E T H J . Me IN T Y P E

WIL LIAM B . C U D L I P

A U G U S T U S C . L E D Y A R D

J O H N G - G A R L I N G H O U S E

WILLIAM A .W A L K E R

D O N A L D R. F L I N T E R M A N N

D A N I E L J . T I N D A L L , J R .

F R E D W F R E E M A N

F R E D E R I C K K. P LUM B

PATRICK J . L E D W ID G E

G E O R G E E. McKEAN

V E R N E C . H A M P T O N , I I

C H A R L E S F. C L I P P E R T

L A W R E N C E M. KELLY

J O H N E . S . S C O T T

J O H N C . O ’ME A R A

J O H N A . K R S U L , J R .

D O U G L A S D. R O C H E

T H O M A S E . O W E N

E D G A R C . H O W B E R T , J R .

R O B E R T S. K R A U S E

R O B E R T P. H U R L B E R T

WILLIAM F. B A V I N G E R , III

J . T H O M A S C A R R O L L , J R.

RALPH S. R U M S E Y

J A M E S N. C A N D L E R , J R .

C O U N S E L L O R S AT LAW

1 7 0 0 N O R T H W O O D W A R D A V E N U E

P . O . B O X 5 0 9

B L O O M F I E L D HI L L S , M I C H I G A N 4 8 0 1 3

T E L E P H O N E ( 3 1 3 ) 6 4 6 - 4 3 0 0

January 29, 1973

C L A U D E H. S T E V E N S

O F C O U N S E L

E D W A R D L . W E 3 E R

D E T R O I T O F F I C E

8 0 0 F I R S T N A T I O N A L B U I L D I N G

D E T R O I T , M I C H I G A N 4 3 2 2 6

T E L E P H O N E ( 313) 9 6 2 - 5 8 6 0

L A N S I N G O F F I C E

117 W E S T A L L E G A N S T R E E T

L A N S I N G , M I C H I G A N - 4 8 9 3 3

T E L E P H O N E ( S I 7 ) 3 7 1 - 1 7 3 0

Michael Kodak, Jr., Esq.

Clerk, Supreme Court of

the United States

Washington, D.C. 20543

Re: Bloomfield Hills School District

v. Hon. Stephen J. Roth

October Term, 1972 No. 72-747

Dear Mr. Kodak:

Enclosed for filing in the above matter please

find forty (40) copies of a Supplement to Petition for

Writ of Certiorari, together with a Certificate of Ser

vice .

The Supplement is filed pursuant to Rule 24

of the Rules of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Very truly yours,

-7

Charles F. Clipperti X - c L

CFC:mak

Enclosures