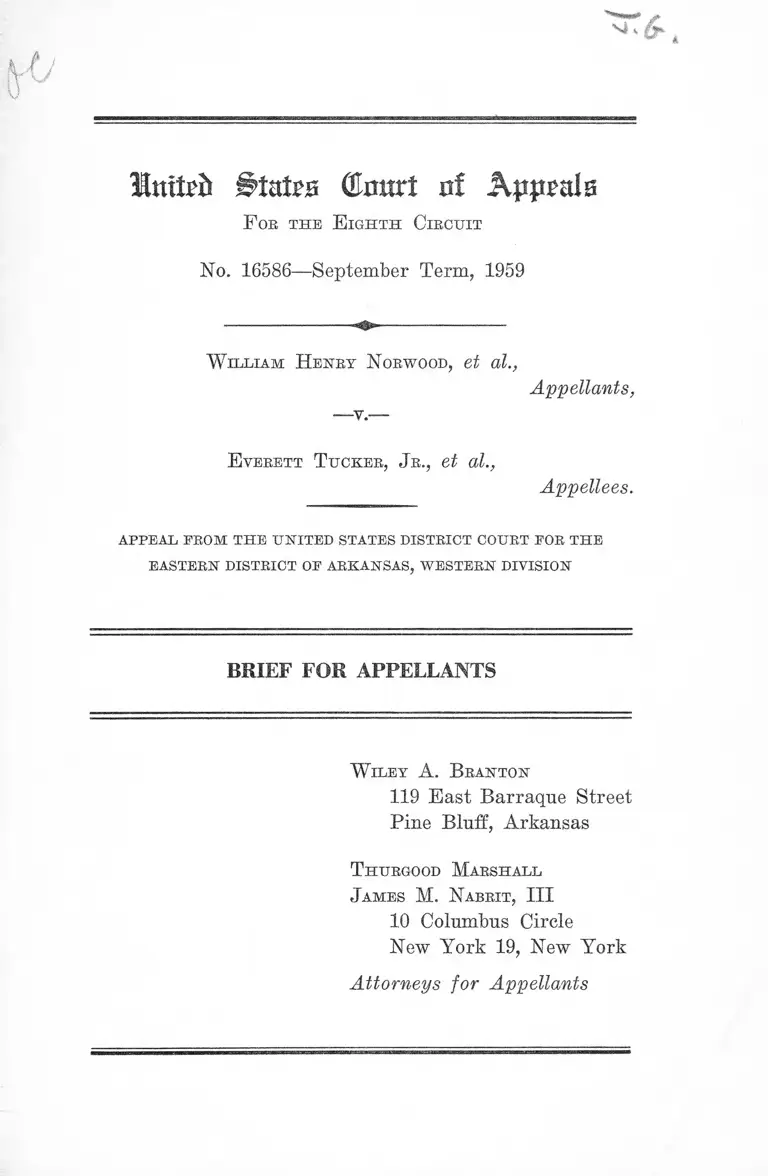

Norwood v. Tucker Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Norwood v. Tucker Brief for Appellants, 1959. d469d108-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9817be07-313b-4d6b-ad15-d063087daca7/norwood-v-tucker-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

llxnti'h Butts (Cmtrt u! Appals

F or th e E ig h t h Circu it

No. 16586—September Term, 1959

W il l ia m H en ry N orwood, et al.,

Appellants,

-v.—

E verett T u cker , Jr., et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OE ARKANSAS, WESTERN DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

W iley A. B ranton

119 East Barraque Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

T hurgood M arshall

J am es M . N abrit , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

S tatem en t of t h e Ca s e ................................................................ 1

Introduction ............................................................... 1

I. Partial History of tlxe Case .................. 2

A. The 1956-1957 Proceedings .............. 2

B. Proceedings from 1957 until June

1959 ...................................................... 3

C. Proceedings Resulting in the Order

of September 2, 1960 ........................ 4

II. Facts About the Original Plan as Indi

cated in the 1956-57 Proceedings ........... 7

III. The Facts at the 1960 Trial Indicating

Current Placement Procedures.............. 13

A. General Organization of Schools;

the Pattern of Continued Segrega

tion ................. 13

B. The Beginning of the Placement Pro

cedures; Preliminary Student Regis

tration and Administrative Proced

ure ........................................................ 17

C. The Board Meeting of July 29, 1959:

Adoption of Local Placement Regula

tion ; Initial Assignment of Students;

Board’s Reasons for Its Actions .... 19

D. Actions and Procedures on Requests

for Change of Assignments; Special

Tests and Interviews; Board Hear

ings

PAGE

24

11

P oints a n d A u t h o r it ie s ......................................................... 27

A r g u m e n t ................................-........................................................... 30

I. The Denial of Injunctive Relief Permits an

Unjustified Modification of the Court-Approved

Desegregation Plan and Impairs Rights of Ap

pellants Secured by the Plan, the Former De

crees, and the Fourteenth Amendment............. BO

II. The Denial of Injunctive Relief Permits the

Permanent Continuation of Racially Discrimi

natory Policies and Procedures Tending to

Preserve Segregation and Thus Deprives Ap

pellants of Rights Protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment .......................................................... 44

III. The Principles Requiring Exhaustion of Ad

ministrative Remedies and Limiting Parties to

Asserting Personal Rights, Do Not Affect Ap

pellants’ Standing to Litigate the Questions

Presented or Their Right to the Relief Prayed 54

C o n c l u s io n .......................................................................................... 57

PAGE

T a b l e o f C a s e s :

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (1956) ...........3, 7,12, 30,

31, 32

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (1957) .............. 3, 7, 30, 32

Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 33 (1958) ................. 32,39,43

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97 (1958) .......................... 39

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark.

1959) .......... -...............-...........................................17,39,43

Avery v. Wichita Falls, 241 F. 2d 230 (5th Cir. 1957) .. 37

I ll

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1953) .................. 56

Bates v. Little Bock, 361 U. S. 516, 4 L. ed. 2d 480,

486 (1960) ..................... ................................................ 38

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954) ..................... 45

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483 (1954) ....3, 44

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) ....36, 37

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956)........... 55

Cities Service Co. v. Securities & Exchange Comm.,

- 257 F. 2d 926 (3rd Cir. 1958) ..................................... 31

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) .............. 4, 37, 38, 39,

40, 44, 45

Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (4th Cir. 1959) .. 55

Dove v. Parham, —— F. 2 d ------(8th Cir. Aug. 1960)

50, 52, 55

Evans v. Ennis,------F. 2 d ------- (3rd Cir., July 1960),

on rehearing------F. 2 d ------- (Aug. 1960) ...............14, 52

Farley v. Turner,------F. 2d-------(4th Cir., June, 1960) 55

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 763

(5th Cir. 1959) ............................................ * .....35,36,55

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 (1896) ............... 44

Hill v. School Board of City of Norfolk, V a .,------F.

2 d ------ (4th Cir. Sept. 1960) .................. ........ ........ . 52

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730

(5th Cir. 1958) ............ ................... ..... ..................... 55

Hopkins v. Lee, 6 Wheat. 109 (1821) ............................. 40

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, Va.,

276 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir., 1960) .....................................52, 53

PAGE

PAGE

Kelly v. Board of Education, 159 F. Supp. 272 (M'. D.

Tenn. 1958) ...................................................................35,

Kelly v. Board of Education of the City of Nashville,

supra, at 159 F. Supp. 275-277 .................................

McCullough v. Virginia, 172 U. S. 102 (1898) ............

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (4th Cir.,

1951) ............................................................................50,

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637

(1950) ............................................. -..............................

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370

(5th Cir. 1960) .........................................35, 37, 52, 54,

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390 (1923) ......................

N A A CP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958) ...............39,

Oklahoma v. Texas, 256 U. S. 70 (1921) ................. -....—

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156

(5th Cir. 1957) .............................................................

Parham v. Dove, 271 F. 2d 132 (8th Cir. 1959) .......... 40,

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925) ....51,

Public Utilities Comm. v. United States, 355 U. S. 534

(1958) ............................................................................

Rippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690 (5th Cir. 1957) ..........

School Bd. of City of Newport News v. Atkins, 246 F. 2d

325 (4th Cir. 1957) ............ -.................................... - -

School Bd. of City of Norfolk v. Beckett, 260 F. 2d

18 (4th Cir. 1958) ...........................................................

Slaughterhouse Cases, 16 Wall. 36 (1873) ......................

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 (1940) .............................

36

36

40

51

50

55

51

56

31

55

,55

,56

56

36

55

51

44

44

V

PAGE

United States v. Johnson County, 6 Wall. 166 (1867) .... 40

United States v. Peters, 5 Cranch 115 (1809)................ 40

United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U. S. 106 (1932) ....41, 42

O t h e b A u t h o b i t i e s :

^ Appellees Brief, p. 7, 243 F. 2d 361.......... ...................... 11

>( Appellees Brief, p. 45, 257 F. 2d 33................................. 40

Arkansas Pupil Assignment Law of 1956 (Initiated Act

No. 2 of 1956) ............................................................... 40

Arkansas Pupil Placement Law of 1959 (Act No. 461

of 1959) .........................................................................39, 40

—-'Civil Eights Act of 1960, Title I, 62 Stat. 769 (1960),

18 U. S. C. §1509 ........................................................... 38

Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence (Symons 5th Ed.)

Vol. 1, Sec. I V ............................................................... 57

Eule 23(a)(3) Federal Eules Civil Procedure ...........56,57

Black, The Lawfulness of the Segregation Decisions,

69 Yale L. J. 421 (1959) 51

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Introduction

This appeal involves another phase of litigation com

menced in February 1956 in which appellants, Negro school

children and parents, have challenged racial segregation in

the public schools of Little Rock, Arkansas. Different

phases of this cause have been before this Court on five

occasions, and twice have been decided by the Supreme

Court of the United States.* 1 2 3 4 5 6

While familiarity with the entire history is helpful in

understanding the matter now before the Court, a descrip

tion of all previous proceedings would unduly lengthen this

statement. Therefore the statement is confined to prior

proceedings directly related to the issues now presented.

This is an appeal from an order dated September 2, 1960,

denying appellants’ motion seeking further relief to re

strain certain actions of the Board of Directors of the

Little Rock School District. The opinion below, dated

September 2, 1960, also expressly declined to further retain

jurisdiction.

1 Previous decisions in this litigation are reported as follows:

1. Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E. D. Ark. 1956), aff’d 243

F. 2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957).

2. Aaron v. Cooper, 2 Eace Eel. Law B. 935 (E. E>. Ark. 1957), aff’d

sub nom. Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F. 2d 808 (8th Gir. 1958).

3. Aaron v. Cooper, 156 F. Supp. 220 (E. D. Ark. 1957), aff’d sub mm.

Faubus v. United States, 254 F. 2d 797 (8th Cir. 1958), cert. den.

358 U. S. 829 (1958).

4. Aaron v. Cooper, 163 F. Supp. 13 (E. D. Ark. 1958), cert, before

judgment of Court of Appeals denied 357 U. S. 566, rev’d 257 F. 2d

33 (8th Cir. 1958), aff’d Cooper v. Aaron, 358 TJ. S. 1 (1958).

5. Aaron v. Cooper, 3 Eace Eel. Law E. 882 (E. D. Ark. 1958), vacated

and remanded 261 F. 2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958), opinion on remand, 169

F. Supp. 325 (E. D. Ark. 1959).

6. Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark. 1959), aff’d sub

nom. Faubus v. Aaron,------ IX. S .------- ■, 4 L. ed. 2d 237 (1959).

2

The opinion and order followed a trial held March 22nd

and March 23rd, 1960, which involved actions, policies and

regulations of the Board under a pupil assignment pro

gram instituted prior to the 1959-60 school term. One

issue was whether the Board’s pupil assignment actions

and regulations improperly modified a plan for desegre

gation approved by the trial court in 1956; this has neces

sitated review of matters involved in the trial of August

15, 1956 (143 F. Supp. 855), and the subsequent appeal

(243 F. 2d 361). (See Tr.8 pp. 262-269, and Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibits 8 and 9.)

This statement is divided into three parts. Part I is a

partial history of the litigation describing the 1956 pro

ceedings in the trial court and proceedings immediately

preceding the present appeal. Part II is a detailed state

ment of facts about the 1955 plan. Part III describes facts

developed at the 1960 trial.

I.

Partial History of the Case

A. The 1956-1957 Proceedings (143 F. Supp. 855 and 243

F. 2d 261).

This case was commenced in February 1956 when Negro

school children and parents sued to restrain the practice

of compulsory racial segregation in the public school sys

tem of Little Rock, Arkansas. This was a class action (Rule

23(a)(3) Federal Rules of Civil Procedure) pursuant to

28 U. S. C. *§1331,1343. 2

2 The typewritten transcript of the hearing held on March 22-28, 1960

is cited herein as “ Tr.” followed by the page number. The 1956 Transcript is

eited as “ 1956 Tr.” ; see note 5 infra.

3

At the first trial, August 15, 1956, the Board admitted

compulsory segregation and acknowledged violating prin

ciples set forth in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483 (1954). However, it interposed as a defense a plan

of procedures for gradual systematic desegregation of the

schools—a plan the Board adopted voluntarily on May

24, 1955. This plan provided for delay until September

1957 in starting desegregation in high schools, and for

even longer delays in ending segregation in junior high and

elementary schools. Plaintiffs objected. The Board under

took to establish that administrative obstacles to desegre

gation resulting from local school problems justified delay

in starting the plan and further delay incident to its three-

phase character.

On the basis of the Board’s showing of administrative

problems and representations as to results which would be

obtained, the trial court held that plaintiffs’ enjoyment of

their constitutional right to non-segregated public educa

tion could be delayed, and that the plan was “adequate” ,

in that it would “ultimately bring about a school system

not based on color distinctions” , 143 P. Supp. 855, 866. The

Court also ordered that jurisdiction be retained during

the period of transition. Plaintiffs appealed, and this

Court affirmed, 243 P. 2d 261. No review was sought in

the Supreme Court.

B. Proceedings From 1957 Until June 1959.

For present purposes, it is important to note that every

proceeding from 1957 until 1959 involved attempts by the

Board, various state officials, and others, to suspend, aban

don, or frustrate the 1955 plan or to prevent any desegre

gation of the Little Rock public schools. The Board three

times applied for permission to “ suspend” the plan, once

attempted to lease school property for racially segregated

operation by “private” persons, and subsequently sought

4

permission to “abandon” the plan and operate segregated

schools pending formulation of a new plan.

In 1958, the Supreme Court met in special session to hear

this case and affirmed this Court’s reversal of an order

granting a suspension in the face of opposition to, and

unlawful interference with, desegregation of the Little

Rock schools, Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1.

In November 1958 the proclivity of the Board and other

state officials for activities interfering with desegregation

caused this Court to direct issuance of an injunction re

straining the Board in broad terms:

. . . from engaging in any other acts, whether in

dependently or in participation with anyone else, which

are capable of serving to impede, thwart or frustrate

the execution of the integration plan mandated against

them (261 F. 2d 97,108; 169 F. Supp. 325, 337).

The Board’s request for permission to “abandon” the

plan and operate the schools on a segregated basis pend

ing submission of a new plan occurred after the above-

quoted injunction, and was participated in by three of its

present members. (The opinion of September 2, 1960

mentions this unreported order at page 10.)

No litigation between 1957 and 1959 necessitated a re

view of the meaning of the 1955 plan, or involved a claim,

such as is now made, that the plan was not being admin

istered in accordance with the representations made to

secure initial approval of the plan.

C. Proceedings Resulting in the Order of September 2, 1960.

On August 8, 1959, the appellants filed a motion for

further injunctive relief, and a motion to substitute as

5

defendants three new members of the Board. The motion

for further relief alleged that the Board had taken certain

actions in initially assigning the plaintiffs and other

Negroes entitled to the benefit of the judgments in this

case, which were inconsistent with, impeded, and frustrated

the effectuation of the court-approved plan for desegre

gation, thereby depriving Negro children of rights pro

tected by the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment and of the benefits of the prior

orders in the case.

The motion alleged that Negro pupils were deprived of

the right to attend the schools in their attendance areas

and had instead been assigned on the basis of race to an

all-Negro school located outside their attendance areas.

It was alleged that this was an impermissible modification

of the court-approved desegregation plan. The plaintiffs

prayed for an injunction

“restraining the defendants from refusing to admit,

enroll and educate the named plaintiffs and intervenors,

and all other Negro students who present themselves

for admission to such of the Little Rock senior high

schools as they may be entitled to enter pursuant to

the prescribed school zones, at normal admission and

enrollment periods conducted during the forthcoming

1959-60 school term and thereafter.”

The defendants responded to the motion for further

relief, on August 21, 1959, alleging: (1) that they were

operating the schools on a nondiscriminatory basis; (2)

that Negro plaintiffs had not completed administrative

procedures established by the Board for obtaining re

assignments; (3) that the plaintiffs could no longer main

tain a class action in this case; (4) that the Board was

entitled to consider many criteria other than residence in

determining school assignments; and (5) that the defen

dants’ actions and assignment procedures were “within

the framework of the governing court orders and decisions.”

The Board prayed that the motion for further relief be

dismissed, and that the trial court “ specifically approve”

the assignment procedures adopted and followed by the

Board.

September 19, 1959, several Negro students and parents

filed a motion to intervene as plaintiffs, adopting the al

legations of the motion for further relief. The court al

lowed intervention by order dated September 24, 1959, and

the response to the motion for further relief was treated as

a response to the intervention.

The cause came on for hearing before the Court on

March 22 and 23, 1960. The motion to substitute defen

dants was granted. The opinion and order of the court

denying plaintiffs’ request for injunctive relief were en

tered September 2,1960.

The court below held that plaintiffs were not entitled

to any relief and concluded that the Board’s assignment

procedures were consistent with the 1955 plan; that the

assignment procedures employed by the Board did not

discriminate racially; that the Board acted in good faith;

and that there was no reason for the court to retain juris

diction.

Plaintiffs filed notice of appeal on September 3, 1960.

This Court on September 13, 1960, directed that the cause

be set for oral argument at the November 1960 session,

the appeal to be heard on the original files of the District

Court.

6

7

Facts About the Original Plan as Indicated in the

1956-1957 Proceedings

It is undisputed and generally known that only nine

Negro students attended Central High School during 1957-

58 (1960 Tr. 272-273), and as stated by this Court in one

of its opinions, 257 F. 2d 33, 34 (8th Cir. 1958)3 the Super

intendent did conduct a “ screening” of Negro pupils prior

to the 1957-58 school term.

But contrary to the conclusions of the court below in its

September 2, 1960 opinion, which repeats the undocumented

and unsupported claims made in the Board’s brief below,4

there was no mention of “ screening” Negro or any students

and no mention of an intention to use any assignment

criteria changing the general attendance area rule in either

the text of the plan, the pleadings, the testimony, or the

exhibits when the plan was presented and approved. There

was no mention of such a policy in either the opinion of

the District Court (143 F. Supp. 855) or the opinion of

this Court (243 F. 2d 361). Likewise there was no mention

of a policy (nowT held to be a part of the plan), permitting

“A child who was assigned to a school wherein his race

was in the minority to transfer to a school wherein his

3 This opinion reversed a ruling allowing a 2 ^ year suspension of de

segregation.

4 The Court wrote, at p. 14:

‘‘One provision of the plan was to permit any child who was as

signed to a school wherein his race was in the minority to transfer

to a school wherein his race was in a majority. It is clear that

there was a re-districting in that attendance areas were fixed. It

is equally clear that student assignment (at that time called “ screen

ing” ) was provided for and permitted by the plan. In fact, at that

time there were approximately as many Negro students eligible for

assignment solely on the basis of attendance areas to formerly all

white schools in 1957 as there are now. The screening then em

ployed under the plan reduced the number to 17, and only 9 at

tended predominantly white schools.” (Emphasis supplied.)

II.

8

race was in a majority.” In fact, contrary representations

were made to the trial court and to this Court in 1956-57.

The facts are as follows:

At the 1956 trial5 the Board represented that each child

in the desegregated grades would have the “basic right”

to attend the school in his attendance area. The Super

intendent testified as follows on direct examination while

explaining the plan, at 1956 Tr. pp. 68-69:

Q. I wanted you to tell us, Mr. Blossom, with concrete

ness, those of the fourteen points that you consid

ered at the time that you drew up the plans that

have been put into practice in connection with the

plan?

A. All right. We have developed attendance areas.

Q. All right?

A. That would give every child the basic right to at

tend school in the area of the legal residents (sic)

of his parents or legal guardian. That’s a concrete

step we have taken. All right. We have made the

studies that reflect the achievement and the ability

of individual children to show us the job we have to

provide the educational development in the school

system of Little Rock School District. (Emphasis

supplied.)

At the 1956 trial the Superintendent testified to a general

policy of assigning students to schools in the areas where

they lived,6 and stated that the areas would be applied as

5 The typewritten transcript of the August 15, 1956 trial was considered

by the court below and has been certified to this court on the instant appeal

(see 1960 Tr. 267-269). In addition excerpts from that transcript are included

in Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 9. In this brief citations to the 1956 transcript are

indicated as “ 1956 Tr.” followed by a page number.

6 The Superintendent testified at 1956 Tr. pp. 106-107:

A. All right, the estimated date, as we have told heTe is to begin in

1957. Now we said two things in that statement— (1) that we

9

generally restrictive boundaries, within which pupils would

be assigned without regard to race.7 It was explained that

were going to follow the general principles laid down; that we

were going to hold the standards of our educational program.

Now our plans call for a grouping o f the children in the at

tendance areas for educational purposes in grades 10, 11, and

IS. That’s estimated ’57. (Emphasis supplied.)

The Superintendent further testified at 1956 Tr. pp. 125-126:

Q. It is the policy of your School District to require that children

attend the school in the school area, attendance area, that they

live, is that true?

A. There are exceptions to it, hut that’s the general policy.

Q. That is your general policy. Your Point 11 here says “ To Pro

vide an Opportunity for All Children of Attending School in the

Attendance Area Where the Residence of Their Parents or Legal

Guardian Is Located.” Now, since that is already your policy,

why do you need time to enforce that?

A. To develop these maps that are in the individual program, it’s

all related.

Q. But you got your maps already?

A. Yes but we don’t have the program completed. It takes more

than maps and just buildings. You can create your area and you

can put them in a seat, but that’s a far-ery different than edu

cating them. The job just begins when you get them in the seats.

Q. But that is true under all circumstances?

A. Yes sir, but each set of circumstances are different and you

can’t just apply one general principle and say that’s it (126), and

have an educational program.

Q. Well when do you think you’ll get that problem solved?

A. Now which particular problem are you talking about?

Q. The problem of getting your program ready for—

A. We have told you that it’s ready at the Senior High School level;

that the Junior High School attendance areas are tentative; at

the time in this phase program there will, in all likelihood have

to be another Junior High School. Now i f we have to bring in

another junior high school to house the number of children be

cause of growth, then those areas will have to be revised. Now if

the growth does not cause the revision of the attendance areas,

they will stand as they are; but i f the children justify an addi

tional school, additional seats, facilities, instructors and so on,

then the necessary changes will be made under the principles as

outlined. (Emphasis supplied.)

7 The Superintendent testified at 1956 Tr. pp. 62-63:

Q. Now, integration can not be commenced until the West End

High School is completed?

A. Under this plan, that is correct.

10

the Board would not be ready to make the change from the

old system of city-wide attendance areas with separate

schools for whites and Negroes until September 1957 at

the high school level.8 It was said that the change to the

new system could not be made until September 1957 when

a high school would be ready at the west end of the city

(Hall High),9 and because the high schools’ curricula had

to be adjusted to provide for the specific needs of all chil

dren living within the newly established attendance areas.

Q. Now why is that, specifically, Mr. Blossom?

A. That is specifically correct so far as I ’m concerned in the prob

lem of dealing with curricula. Now we have three attendance

area at the present time that affect senior high school children—

Central High School, Horace Mann High School and Little Hock

Technical High School. The attendance area for Little Bock

Tech High is city-wide; the attendance area for Little Bock

Central High School is city-wide; the attendance area for Horace

Mann High School is city-wide. Now when we change from city

wide attendance areas to geographical areas within the city, that

restrict a certain group of youngsters to one area— to one build

ing, we create problems that deal with our curriculum of planning

the curriculum for the needs of those specific children. . . .

(Emphasis supplied.)

At 1956 Tr. p. 91 the Superintendent testified:

A. I am saying that the putting of the races together in different

attendance areas because of different children, as reflected on

these exhibits here, on the attendance areas, that the fact that

under our present system at the senior high school area our pro

gram is city-wide. So, all of the white children are embraced in

that program, all of the colored children are embraced in another.

When we restrict the geographic areas we restrict that to a cer

tain group of youngsters. Now, it is justified, reasonable and

sensible to take the time to plan the basic program for the in

dividual group of youngsters in a specific area and to try to at

tain the second educational objective of providing the program

that serves the specific needs o f the individual children. Now

when you do that, you concentrate a different type of program

for a specific set of needs and—

8 See note 7 supra.

9 See note 7 supra. The statement that the plan could not be started

until the city had 3 high schools is contained in the text of the plan; see

143 E. Supp. 855, 859 (paragraph called “ Time for integration” ).

10 See notes 6 and 7 supra. See also 1956 Tr. pp. 45-50, passim.

11

The attendance areas system of assignment was the matrix

of the plan, and the areas were first established in connec

tion with the plan by locating* all pupils—colored and

white—on spot maps and then drawing the zone lines with

reference to the residences of all pupils and the capacities

of the school buildings.11

The Board represented during the 1957 appeal that

under the plan pupils would be assigned to the schools in

their attendance areas without regard to race. In its brief

in this Court the Board made the following statement

(Appellees’ Brief, p. 7, 243 F. 2d 361, 8th Cir., No. 15,675):

“ Integration will start in the high schools as of

September, 1957. At that time 582 Negro pupils will

receive education in an integrated school system (R.

63). In 1958, 292 Negro pupils who will graduate from

junior high schools will have the same opportunity

(R. 62). In 1959 355 will move into the integrated sys

tem, and in 1960 406 will be admitted (R. 62). By that

time the junior high schools will be integrated, and that

means that all pupils presently in the top three grades

of elementary schools will also be in integrated schools

by 1960. All Negro pupils now attending Little Rock

schools as of September, 1957, will be bound to ex

perience education under the integrated system before

finishing their courses.” 12

The record references in the above quote are to the pages

of the printed record which summarize exhibits,13 indicat

ing the numbers of pupils attending the various grades,

11 See 1956 Tr. pp. 31-38. See also Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 8 from the 1960

trial— a summary of the contents of Exhibits C, D, E, F, G, and H from the

1956 trial. The original 1956 exhibits are no longer available in the court

records as indicated at 1960 Tr. pp. 262-264.

12 This representation was brought to the attention of the court below;

Tr. 264-266.

13 The same information is now contained in Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 8.

12

and the numbers of colored and white pupils in each at

tendance area (see note 11 above). The testimony and

the manner in which the enrollment figures were presented

in the Board’s 1957 brief in this Court make it plain that

the plan contemplated a “ general policy” (1956 Tr. 125-

126) of assigning both Negro and white pupils to high

schools on the basis of residence in the areas. For ex

ample, one figure mentioned in the quotation is “ 582”

Negro pupils. It was said that “582 Negro pupils will re

ceive an education in an integrated school system” in 1957.

The “582” pupils mentioned were all of the Negro high

school students in the system. Thus it was represented

that white students would be assigned to Mann High and

Negro students to Central if they lived within the zones

prescribed for those schools. This is clear in light of the

testimony about the “ restrictive” nature of the boundaries.

Mann, presently an all-Negro high school, was not an

old “Negro” school established under the “ separate but

equal” system. Rather, Mann was a new building opened

in February 1956, which had been originally planned as

a junior high school, and which was said to have been

redesigned as a high school “ to fit into this [desegregation]

plan . . . in order . . . [to do] . . . the job of providing

adequate attendance areas that would serve the needs of

the children.. . . ” 14

The texts of the Board’s public announcement of May

20, 1954, and the plan approved May 24, 1955, both advert

to attendance areas (143 F. Supp. 855, 858-59). The rea

son stated in the plan for the long period of delay neces

sary before elementary schools could be desegregated was

the fact that attendance areas were more difficult to estab

14 See 1956 Tr. p, 53.

13

lish at the elementary level.15 Likewise, the delay in de

segregating the high schools from the adoption of the plan

in May 1955 until September 1957 was justified by the

need to build additional high schools (including Mann,

completed in 1956, and the west end (Hall) school which

was completed in 1957), in light of the proposed attendance

area system of pupil assignment.16

III.

The Facts at the 1960 Trial Indicating Current

Placement Procedures

Appellants’ general factual claims are: (1) that the

Board’s present actions and procedures governing the

placement of pupils constitute a substantial modification

of the assignment policies set forth to obtain approval of

the 1955 plan, and (2) that its actions and procedures

governing both initial assignments and changes of assign

ments subject Negro pupils and parents seeking desegre

gated assignments to different and unequal treatment, and

operate to allow a small “token” number of Negro children

to attend predominantly white schools while perpetuating

the general rule of compulsory racial segregation.

A. General Organisation of Schools; the Pattern of Continued

Segregation.

It is undisputed that all elementary schools (grades 1-6)

and junior high schools (grades 7-9) in Little Rock are

still operated under a policy of complete and compulsory

15 143 F. Supp. at 860:

“ 6. The establishment of attendance areas at the elementary level

(grades 1-6) is most difficult due to the large number of both

students and buildings involved. Because of this fact it should

be the last step in the process.”

16 See notes 7 and 14 supra.

14

racial segregation.17 Four senior high schools (grades 10-

12) are maintained in the system (Tr. 40): Technical High,

which has a city-wide attendance area, specializes in “trade”

education, and in 1959-60 served 175 white male students

(Tr. 42, 77, 41); Mann, Central, and Hall offer general

high school curricula (Tr. 77-78), and have the same at

tendance areas established as a part of the 1955 plan, ex

cept for one change in the Hall-Central boundary;18 Mann

is an all-Negro school which had an enrollment during the

1959- 60 term estimated at 700 students,19 Hall enrolled an

estimated 700 students, only three of whom were Negroes

(Tr. 41), and, during the 1959-60 term, Central enrolled

around 1600 students, including only five Negroes (Tr. 41).

The record does not indicate enrollment figures for the

1960- 61 term,20 but press reports indicate that the racial

distribution remains generally the same with 12 Negro

pupils now assigned to the two predominantly white high

schools.21

During the 1959-60 school term the residence statistics

for pupils in the three high school attendance areas were

(Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1) :

17 See Defendants’ Exhibit 5, a resolution stating the board’s intention

not to extend desegregation to the junior high school level in 1960-61.

18 Tr. 43. See plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1 (map). None of the high schools are

overcrowded; 1960 Tr. 89. See note 36, infra, about “ registration” areas.

19 Tr. 41. The total was probably closer to 600 pupils; cf. Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit 1 indicating a total of 638 Negro high school students.

20 The trial took place before the assignments. 1960 Tr. 204.

21 New York Times, September 7, 1960, p. 29, col. 6. I f the Board desires,

appellants would readily stipulate that it could supply the current enrollment

statistics to the District Court by affidavit and certify them to this Court, as

was suggested recently in Evans v. Ennis (3rd Cir., Aug. 29, 1960),------ E. 2d

------ (on rehearing).

15

White Negro

Pupils Pupils Totals

Mann H. S. Area ......... ..... 202 277 579

Central H. S. A rea ...... ...... 1412 349 1761

Hall H. S. Area .......... ..... 677 12 689

Total ________ ..... 2291 638 3029

These figures indicate only the residence pattern, not the

placements.

The pattern of high school placements can be explained

in terms of two general principles,22 with exceptions as

indicated:

1. White pupils were generally placed in schools where

they registered in accordance with the attendance areas,23 24

except that all of the 200 white pupils living in the Mann

area were placed at Central under racial “ options” for

registrants.24. No white pupils who registered at the school

in their attendance areas were refused assignment at that

school.25

Exceptions: A small number of white students were

permitted to move from Hall to Central and vice versa:

Twenty white students registered outside their areas and

were initially assigned where they registered; 26 27 about

twenty-four others were granted transfers outside their

areas after applying for reassignments.37

22 See generally Tr. 200-203.

23 As indicated in the sources cited in notes 26 and 27 below, only 20

white students were not assigned on an area basis initially, and only 24 others

obtained changes of the initial assignments.

24 Defendants’ Answer to Interrogatory No. 6, pp. 3-10. See also Plain

tiffs’ Exhibit 2.

25 Defendants’ Answer to Interrogatory No. 4.

26 Defendants’ Answer to Interrogatory No. 6, pp. 1-2.

27 Defendants’ Answer to Interrogatory No. 2, part A, indicates that 24

of 32 white applicants were granted changes of initial assignments.

16

2. Generally Negro students were placed at Mann High

School without regard to area of residence, or place of reg

istration.™ Although, fifty of the 349 Negro pupils living

in the Central area registered at Central, most were placed

at the all-Negro Mann High.

Exceptions: Three Negroes initially assigned to Hall,

and three to Central;28 29 three other Negroes admitted to

Central after reassignment hearings.30 All of these students

lived in areas where admitted. (One of nine Negroes ad

mitted to Central did not attend in 1959-60, having re

ceived a diploma.)

The manner in which the Board accomplished the pat

tern described above was complicated and can be explained

only by the detailed description of the Board’s actions,

policies and procedures which appears below.

The school district has continued the policy of hiring

and assigning teachers on the basis of race at all grade

levels.31

Each of the three general high schools in the system

serves pupils with varied levels of ability and academic

achievement.32 There is no program of homogeneous abil

ity-grouping by high schools, but only within each school.33

28 As indicated in Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1, more Negro pupils lived outside

the Mann area than within that area. Only 9 Negroes were assigned to Hall

and Central and only 8 actually attended. See notes 29 and 30 below.

29 The names of these six students are included in Defendants’ Answer to

Interrogatory No. 1.

30 These three students are indicated in Defendants’ Answer to Interroga

tory No. 3.

31 Tr. 47, 319-20; see: Minutes Beg. Mtg., June 25, 1959, Defendants’ Ex

hibit 2.

32 See generally Tr. 73-86.

33 The exception is Technical High— recommended for students with me

chanical aptitude; Tr. 80. Each of the three general schools has the same basic

school program.

17

That is to say, there is no school building set aside solely

for slow-learners or fast-learners or solely for advanced

students or retarded students (Tr. 75-76), hut each school

has classes in which students are grouped by ability or

achievement level.34 The basic qualification for admission

to the three general high schools is simply successful com

pletion of the lower grades and promotion to the 10th grade

(Tr. 78, 79).

B. The Beginning of the Placement Procedures; Preliminary

Student Registration and Administrative Procedures.

Throughout the 1958-59 school year the high schools

were closed pursuant to state laws operating to prevent

desegregation, which were held invalid on June 15, 1959,

in Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark.). (See

Tr. 43.) One week after the McKinley decision the Board

resolved to reopen the schools and to use the Arkansas

Pupil Assignment Law (Act No. 461 of 1959).35

On July 14, 1959, the Board issued a pre-registration

announcement for all high school students, and also pub

lished amended attendance area boundaries for Hall and

Central High Schools (Defendants’ Ex. 2—Minutes Spec.

Mtg., July 14, 1959). The change added a small part of

the Central area to the Hall area (Tr. 43). The registration

announcement directed high school students to register

during the period July 21-24, 1959 (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2).36

The announcement expressly referred to the race of stu

34 Tr. 78. In addition, there are “ special education” classes for handicapped

children; Tr. 73.

35 Defendants’ Exhibit 2— Minutes Spec. Mtg., June 25, 1959.

36 It should be observed that while the Board now insists upon using the

term “ registration areas” instead of “ attendance areas” (of. Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit 6— Defendants’ Answers to Interrogatories), the Board’s registration an

nouncement of July 14, 1959, used the phrase “ attendance areas” (Tr. 50) ;

and “geographically” the areas are the same (Tr. 51).

18

dents, providing optional places of registration based on

race.37

During the prescribed period the majority of the high

school students in the system registered (Tr. 54). Fifty-

nine Negro students (including all the plaintiffs) regis

tered as follows: Central—50 pupils; Hall—6 pupils;

Technical—3 pupils.38

The registration procedure operated as follows:

1. Each student was given a mimeographed notice which

admonished him to be certain that he was “ eligible” to

register at that school (Defendants’ Exhibit 21, Tr. 362-63).

2. Each student completed a form called “Request for

Admission to the Little Rock Public School System”

(Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3 is a specimen). The form contained

questions about the pupil’s residence, past school atten

dance, courses desired, and other details. A space was

provided for the registrars to indicate the pupil’s atten

dance area on the form. No space was provided for a

student to indicate a choice of schools, and the only pro

cedure for a student to indicate his desire was to appear in

person at his chosen school (Tr. 52-53).

37 Superintendent Powell read this provision at Tr. 50:

A. (Beading) “Place of Registration: Tech. High. All students de

siring to attend Tech High will register there. Hall High School:

All students in the Hall High attendance area will register at

Hall High except that the Negro students in the Hall High at

tendance area, who elect to do so, may register at Horace Mann

High School. Central High: All students in the Central High

attendance area will register at Central High, except that Negro

students in the Central High attendance area, who elect to do so,

may register at Horace Mann High School. Horace Mann High

School: AH students in the Horace Mann High School attendance

area will register at Horace Mann High School, except that white

students in the Horace Mann attendance area, who elect to do so,

may register at Central High School.”

38 See Defendants’ Answer to Interrogatory No. 1— Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 6.

19

3. Each student wrote his name and address on a postal

card, later used to give notice of his assignment (Tr. 52-53;

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 4 is a specimen card).

4. School registrars marked the letters “ C-PP”—an

abbreviation for the words “colored, pupil placement”—on

the “Request for Admission” forms of Negro students who

registered at Central (Tr. 138-139).

5. The “ request for admission” forms (which contained

all of the information) were retained at the several schools,

but the postal cards (which contained only names and ad

dresses) were forwarded to the Superintendent’s office in

bundles from each school (Tr. 131).

6. The individual record folders of the 59 Negro stu

dents who registered at Central, Technical and Hall, were

gathered at the Superintendent’s office at the request of

the School Board; also forwarded to the central office were

the files of white students who lived in the Hall area but

registered at Central, and those who lived in the Central

area but registered at Hall (Tr. 115-116; 120-121).

C. The Board Meeting of July 29 , 1 9 5 9 : Adoption of Local

Placement Regulations; Initial Assignment of Students;

Board’s Reasons for Its Actions.

On July 29, 1959, the Board met and adopted regulations

“ for the assignment of pupils, for the reassignment of

pupils, and for the processing and hearing of applications

for reassignment of pupils.” 39 The regulations provided,

inter alia, for the assignment of high school students by

the Board, upon the recommendation of the Superintendent

(Article I ; Art. 11(a)(3); Art. 11(b)(1)). Parents who

object to assignments are required to do so on written

notarized forms within 10 days after initial assignments;

39 These regulations are set out in full in footnote 2 of the opinion below.

20

to appear in person at hearings before the Board; and to

submit to the Board’s investigations (Art. III). Article Y

of the regulations provides standards for initial assign

ments and reassignment requests, which incorporate the

sixteen criteria listed in the Arkansas pupil assignment

law (Act No. 461 of 1959), and “all relevant matters” . The

regulations contain no prohibition against consideration

of race in assigning pupils.

After adopting the regulations, the Board proceeded

to assign “around 2600” high school students en masse

(Tr. 119). The Superintendent did not attend this meet

ing (being absent from the city), and the Assistant Super

intendent insists that he did not make recommendations

for assignments (Tr. 128). But it is clear that the Board

assigned most students by merely adopting long lists com

piled by the staff from the postal cards mentioned above.40

The Board made no attempt to apply its “ assignment

criteria” to the two thousand or more students initially

assigned on July 29th.41 The criteria were applied only to

eleven Negro students on initial assignment.42 The Board

assigned the balance of the students to what the Board

called their “normal schools” .43 These “ normal” assign

ments effected placements in accordance with the “ two

general principles” used to analyze the placement pattern

in this brief, supra, at pages 16-17. Of the eleven Negroes

40 Tr. 132. The lists are attached to the minutes of the July 29, 1959

meeting—Defendants’ Exhibit 2.

41 Tr. 166-168; 184-185. See generally Tr. 143-148; 156-57, 162; 1955—

198; 200-203. See also Defendants’ Answers to Interrogatories 6 and 7

(Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 6).

42 Ibid. These eleven students were five Negroes who had attended Cen

tral during the 1957-58 term; and six Negroes who sought admission to Hail

High.

43 With regard to “ normal” assignments see: Tr. 195-198, 200-203 and

156-157.

21

“ screened” , three were admitted to Hall and three to Cen

tral. The rest were relegated to Mann High (Tr. 184).

At the initial assignment meeting the Board did not

apply its assignment “ criteria” by studying the individual

files of any other students (Tr. 167)—not even to the 48

other Negroes44 who had sought admission to Central and

Technical or to the twenty-odd white students45 who regis

tered outside their attendance areas. These forty-eight

Negroes were also relegated to the segregated Mann school46

although only one47 of them lived in the Mann area; but

the 20 white students were allowed to attend schools out

side their areas48 without the application of any criteria

or review of their files.

In summary, students were generally initially assigned to

the schools in accordance with the registration announce

ment, except for 53 of the 59 Negroes who registered at

previously all-white schools.

Students were notified by post cards of their initial as

signments after the June 29,1959 meeting.

On August 4, 1959, the Board decided to open the high

schools three weeks early and announced that August 12,

1959, would be the first day of school (Minutes of Regular

Mtg., Aug. 4, 1959—Defendants’ Exhibit 3; of. Tr. 209).

The Board’s reasons for its initial assignments were

set forth in the answers to Interrogatories 6 and 7, quoted

44 The names are listed in Defendants’ Answer to Interrogatory No. 1.

45 The names are listed on pages 1 and 2 of Defendants’ Answer to In

terrogatory No. 6.

46 See note 44 supra.

47 See Defendants’ Answer to Interrogatory No. 5 (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 6).

48 See note 45 supra.

22

in the margin below.49 The reasons are expressly related

to the racial pattern of school enrollments and the theory

that it would be detrimental to the Negro students and the

school program if they were “ assigned to a school where

their race was in the minority during a crucial time of the

transition period.” The Board contended that it was to

the advantage of the Negro students not to be assigned

to predominantly white schools where they were “isolated” ,

49 Answer to Interrogatory No. 6:

“ These students had previously attended the school at which they

registered and/or had registered at a school where their race was in

a majority, and the registrations were generally consistent with a

balanced teacher, classroom and school capacity for the high schools

of the District. Therefore, due to the multitude of problems and

details confronting the Board requiring practically around-the-clock

attention in getting the closed schools open, the Board had no al

ternative but to make the initial assignments that appear on the

attached schedule to this Interrogatory and Interrogatory No. 7.”

Answer to Interrogatory No. 7:

“ With regard to the 59 students listed in answer to Interrogatory

No. 1, six were assigned to the school at which they registered.

Thelma Mothershed and Melba J. Patillo were assigned to Mann

High School due to a determination by the Board in the case of

Melba J. Patillo that she had been unable to make the necessary

adjustment to pursue her educational studies at Central High School

where she had previously been in attendance. The assignment of

Thelma Mothershed was based upon the Board’s determination,

from information available to it, that due to an impairment in her

health it would be to her best interest to be in a one-storied school

building instead of a multi-storied school building. With regard

to the remaining 51 students listed in Interrogatory No. 1, their

assignments were based upon a determination by the Board that it

had insufficient information, and insufficient time in which to obtain

the necessary information, with regard to those individual stu

dents to justify initial assignment to a school where their race was

in the minority during a crucial time of the transition period. The

extreme pressures of time and problems have been referred to in

the answer to Interrogatory No. 6, and the Board knew there would

be adjustment problems for the Negro students and the white

students which could be detrimental to both the individuals and the

educational program. Thus, for these reasons and in view o f the

publicized procedure for reassignment and the opportunity aiforded

thereby for the Board to obtain sufficient facts and give proper at

tention to the matter, it was determined that the proper procedure

was to assign the remaining 51 Negro students to Horace Mann.”

23

unless they were “ screened,” because they might have ad

justment problems.50

One Board member candidly acknowledged the difference

between the pupil placement procedure and the court-

approved plan, stating that pupil placement gave the

Board “a little bit of leeway” (Tr. 148-49); but another

member said that he did not recognize that a child had the

basic right to attend the school within his attendance area

under the court-approved plan (Tr. 188-89).

A Board member acknowledged a statement attributed

to him by the press that: “The Board’s most troublesome

problem has been to integrate a large enough number of

Negroes to satisfy the Federal Courts and a small enough

number to satisfy the reluctant white residents of Little

Rock”, (Tr. 163-164) and asserted his view that five Negroes

at Central High was “ enough for this year” (Tr. 164, 152-

155).

The Board members said that the administrative staff

was new; that the Board was also new and inexperienced

in running the schools; that they spent a great deal of time

in meeting to plan for the opening of schools, and in making

arrangements for the physical security of the schools. The

Board chairman explained that the Board thought it would

be on “ safer ground to assign [Negro children] to a school

where their race was in the majority” (Tr. 323), and that

the Board “ did not want to get in a position or approach

the question of having the schools in turmoil or confusion

or the possibility of having them closed or having a special

session of the Legislature called that would pass additional

Acts that would create more confusion” (Tr. 325).

50 Testimony of Psychiatrist, Dr. Peters, 1960 Tr. 336-349. This witness

did not examine any of the pupils involved in the ease, did not consult with

the school board in making its decisions (Tr. 345), and had conducted no

formal research relating to psychological problems connected with segregation

or desegregation (Tr. 347).

24

D. Actions and Procedures on Requests for Change of Assign

ments; Special Tests and Interviews; Board Hearings.

Seventy-six students (19 Negro and 57 white pupils)

filed requests for changes of assignment under the place

ment regulations. Seventeen Negroes and thirty-two white

students actually attended reassignment hearings (An

swers to Interrogatories 2 and 3). Ten of the Negro

students who attended hearings were plaintiffs in this case,

while four of the plaintiffs did not file re-assignment re

quests (Tr. 10).

All of the Negro students who had reassignment hearings

lived in the areas of the schools which they sought to at

tend while none of the white students who had reassign

ment hearings lived in the areas of the schools which they

sought to attend (Tr. 87; Answers to Interrogatories 2 and

3).

The procedures established by the Board included social

worker interviews of pupils and parents, special intelli

gence tests, and hearings.

Of the 49 students who had hearings before the Board,

all of the 17 Negroes and their parents were summoned to

attend social worker interviews, while only 3 of the 32

white students were summoned to interviews (Tr. 225-26

and Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 7). Among the same group of 49

students, all 17 Negroes were required to take the Stanford-

Binet Intelligence test, while only 6 of the 32 white students

were summoned to the tests (Tr. 240-241), and three of the

six white students tested were handicapped students at

tending “ special education” classes.51

51 “ Special education” pupils are regularly tested when they enter the

special program or when the staff feels they need a new evaluation (Tr. 241-

42).

25

The Stanford-Binet test requires about one and one-half

hours per pupil to administer, and must be given by a

skilled tester (Tr. 243). The Stanford-Binet test is not

a part of the system’s “general testing program” which

consists of standardized “group” tests of intelligence

and achievement routinely administered by teachers to all

pupils (Tr. 235-237). Likewise, the social worker inter

views and case-studies are routinely used only for stu

dents having attendance or truancy problems, and occa

sionally with “tuition” pupils and those who move (Tr.

231-32).

With respect to the 23 pupils tested, detailed reports

were made by the school psychologist summarizing the

Stanford-Binet results, and each pupil’s complete school

record (Tr. 242-43), and the psychologist also made oral

reports to the Board in executive session prior to the hear

ings of some students, outside the presence of the pupils

and parents (Tr. 110-111. See, for example, Minutes of

Hearings Held September 8, 1959—Defendants’ Exhibit

4).

Among ten plaintiffs tested, eight of them obtained IQ

scores within the normal range and two scored slightly

above the normal range (Tr. 246-47). Although the Stan

ford-Binet test is not given to all students, the school psy

chologist stated that she was sure that there were students

at Hall and Central High Schools with IQ scores lower

than any of the plaintiffs (Tr. 248).

No standard objective personality tests, primarily de

signed to gain information about emotional development

and personality, were administered as a part of the pupil

placement procedure (Tr. 236-37), but teacher comments

were included in the written reports.

The hearings conducted by the Board were held on

August 4, and September 2, 4, 8, and 9, 1959 (see Minutes,

26

Defendants’ Exhibits 3 and 4). At the hearings the chil

dren and parents were asked to make statements and were

then questioned and cross-questioned by the Board mem

bers, staff, and school board attorneys (Tr. 70-72). The

Board chairman testified that an effort was made to make

the hearings “ informal.” However, even a cursory exam

ination of the hearing minutes reveals that the hearings of

white children were typically brief and perfunctory,52 while

the hearings of Negro children involved lengthy and de

tailed interrogations of students and parents. For ex

ample the minutes of the special meeting on September 2,

1959, contain the hearings of six white students and one

Negro student, and the reporter’s notes of the Negro stu

dent’s hearing fill as many (or more) pages than the hear

ings of the six white pupils combined. Compare also the

Minutes of the August 28th hearings (13 white students)

with the Minutes of the September 8th hearings (7 Negro

and 2 white students).

The hearing of one Negro student became a long ani

mated debate between the parent and the Board on issues

such as segregation, the Board’s “good faith” , and the

reason for the present lawsuit (see Hearing of William

Massey—September 9, 1959). Subsequently, this pupil was

rejected by the Board on the theory that: “While an atti

tude of ‘sticking up for one’s rights’ is normally to be

commended, this attitude could create an unbearable prob

lem from the standpoint of the Board’s efficient and effec

tive operation of the schools in an extremely difficult transi

tion period” (Defendants’ Exhibit 6-AA).

After the hearings the Board acted on the requests.

Twenty-four of the thirty-two white applicants were

granted transfers out of their attendance areas, while

52 Despite this, one white child burst into tears during a hearing. The

Board chairman opined that there was “ no provocation whatever” , Tr. 331-332.

27

only three Negro applicants were permitted to attend the

schools in their areas and the other fourteen Negroes were

required to remain in Horace Mann School (see Answer to

Interrogatories 2 and 3). The fourteen rejected Negro

applicants included all reassignment applicants who had

intervened in this case.

POINTS AND AUTHORITIES

I.

The denial of injunctive relief permits an unjustified

modification of the Court-approved desegregation plan

and impairs rights of appellants secured by the plan, the

former decrees, and the Fourteenth Amendment.

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (1956);

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (1957);

Oklahoma v. Texas, 256 U. S. 70 (1921);

Cities Service Co. v. Securities & Exchange Comm.,

257 F. 2d 926 (3rd Cir. 1958);

Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 33 (1958);

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d

763 (5th Cir. 1959);

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d

370 (5th Cir. 1960);

Kelly v. Board of Education, 159 F. Supp. 272

(M. D, Tenn. 1958);

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955);

Rippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690 (5th Cir. 1957);

Avery v. Wichita Falls, 241 F. 2d 230 (5th Cir.

1957);

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958);

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516, 4 L. ed. 2d 480

(1960);

28

Civil Rights Act of I960, Title I, 62 Stat. 769

(1960), 18 U.S.C. §1509;

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958);

1959).

Arkansas Pupil Placement Law of 1959 (Act No.

461 of 1959);

Hopkins v. Lee, 6 Wheat. 109 (1821);

McCullough v. Virginia, 172 U. S. 102 (1898);

United States v. Peters, 5 Cranch 115 (1809);

United States v. Johnson County, 6 Wall. 166

(1867);

Arkansas Pupil Assignment Law of 1956 (Initiated

Act No. 2 of 1956) ;

Parham v. Dove, 271 F. 2d 132 (8th Cir. 1959);

United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U. S. 106 (1932);

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark.

1959);

II.

The denial of injunctive relief permits the permanent

continuation of racially discriminatory policies and pro

cedures tending to preserve segregation and thus de

prives appellants of rights protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954);

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954);

Cooper v. Aaron, supra;

Dove v. Parham, ------ F. 2d ------ (8th Cir. Ang.

1960);

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S.

637 (1950);

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (4th Cir.

1951) ;

29

School Board of City of Norfolk v. Beckett, 260 F.

2d 18 (4th Cir. 1958);

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390 (1923);

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925);

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, Va.,

278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960);

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, supra;

Evans v. Ennis, ------ F. 2d ------ (3rd Cir. July

1960);

Hill v. School Board of City of Norfolk, V a.,------

F. 2d------(4th Cir. Sept. 1960).

III.

The principles requiring exhaustion of administrative

remedies and limiting parties to asserting personal

rights, do not affect appellants’ standing to litigate the

questions presented or their right to the relief prayed.

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, supra;

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, supra;

Farley v. Turner,------F. 2d ------ (4th Cir. June

1960);

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d

730 (5th Cir. 1958);

Dove v. Parham, supra;

Parham v. Dove, supra;

Public Utilities Comm. v. United States, 355 U. S.

534 (1958);

Carson v. War lick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956);

Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (4th Cir.

1959);

School Board of City of Newport News v. Atkins,

246 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1957);

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d

156 (5th Cir. 1957).

30

A R G U M E N T

I.

The denial of injunctive relief permits an unjustified

modification of the Court-approved desegregation plan

and impairs rights of appellants secured by the plan, the

former decrees, and the Fourteenth Amendment.

The 1955 plan was presented in 1956 as the Board’s

defense to the prayer for immediate injunctive relief, and

was judicially approved upon a determination that admin

istrative obstacles to desegregation justified delay in the

enforcement of Negro children’s constitutional rights. The

plan was held “ adequate” in that it would “ultimately

bring about a school system not based on color distinctions” ,

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855, 866 (1956). The effect

of that decree was to delay all relief until September, 1957,

and to delay further the enforcement of Negroes’ rights in

junior high and elementary school grades. This Court af

firmed, rejecting the appeal of the Negro pupils, Aaron

v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (1957).

It is submitted that the 1955 plan has now been modified

by the adoption of policies discarding the very aspects of

the plan used to justify the original delay, and which for

merly insured that the plan would “ultimately bring about

a school system not based on color distinctions.” The de

termination requires a comparison of the two plans.

The inquiry with respect to the original plan is similar

to that made when res judicata is urged as a defense to a

claim, in that—“What was involved and determined in the

former suit is to be decided by an examination of the record

and proceedings therein, including the pleadings, the evi

dence submitted, the respective contentions of the parties,

31

and the findings and opinion of the court . . . ” , Oklahoma

v. Texas, 256 U. S. 70, 88 (1921); Cities Service Co. v.

Securities & Exchange Comm., 257 F. 2d 926, 930 (3rd Cir.

1958). There is no conflicting evidence about the meaning

of the 1955 plan; no extrinsic evidence was offered at the

1960 trial to explain the prior proceedings. The records of

the 1956 proceedings are the only relevant sources on this

issue, and this Court now has the same documentary record

made available to the District Court.

When viewed as a whole the 1956 proceedings make it

plain that the original plan contemplated the assignment

of students without regard to race on the basis of non-

racial attendance areas.53 True the text of the plan does

not explicitly state this, though it does indicate that prob

lems related to the attendance areas were reasons offered

for delay.54 But the Board’s own presentation in 1956 was

unequivocal. The Superintendent, flatly stated that all

pupils would have the “basic right” to attend the schools

in their areas;55 that pupils would be generally restricted

in their areas by the new system ;56 that the “general policy”

would be to require students to attend the school in their

areas ;57 and that curricula would be planned to implement

the attendance area grouping.58

The 1956 opinion (143 F. Supp. 855) did not recite all

of the evidence, but it was clear that the uncontradieted

presentation of the Board was accepted by the Court when

it found that an objective of the plan was “ to provide the

opportunity for children to attend school in the attendance

area where they reside” (at 860). That opinion quoted the

53 See generally Statement of the Case, part II,

54 143 F. Supp. 855, 859, 860.

55 1956 Tr. 68-69.

56 1956 Tr. 62-63; 91.

57 1956 Tr. 125-126.

58 1956 Tr. 106-107.

32

Board’s plan and its provision that desegregation could

not be started until completion of an additional high school

(at 859), and that desegregation of junior high and ele

mentary schools must be deferred even longer (at 860).

These delays were justified on the ground that time was

needed for establishment of attendance areas, which was

more difficult at the lower levels due to the greater num

bers of pupils and buildings involved. Both the District

Court and this Court held, on the representations made

by the Board, that the plan was one which would accom

plish desegregation of the high schools in 1957, and the

eventual complete desegregation of the entire system “not

later than 1963” (143 F. Supp. at 861; 243 F. 2d at 362).

The Board’s present position is that it is bound only

to end total segregation by some procedure, while appel

lants urge that the Board must completely eliminate segre

gation as proposed in the 1956 proceedings and must do

more than break the pattern of total segregation by “token”

desegregation. To support the position that it is operat

ing “ on a non-discriminatory basis” within the “general

framework” of the plan, the Board points to the well-

known fact that only nine Negro pupils attended Central

High School in 1957-58. However, the record of what the

Board represented in 1956 is still clear. The fact that all

Negro children did not receive the benefits promised can

not eradicate the promise of the plan or the decrees which

confirmed that promise.

The argument that a statement by this Court, subsequent

to approval of the plan, Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 33, 34

(1958),59 concludes the matter, is founded upon identical

59 In the opinion considering the 2% year suspension request this Court’s

summary of the facts included this sentence:

“In conformity with the plan, and under the direction of the Superintendent

of Schools of the Little Kock School District (hereinafter called “ Dis

trict” ), approximately 60 Negro students were meticulously screened prior

to the opening of schools in September, 1957.”

33

reasoning. While this Court in August 1958 used the words

“ in conformity with the plan”, the issue now presented—

the meaning of the plan—was not an issue before this

Court in 1958. The Court’s statement indicated only the

facts about what was done after the Board secured ap

proval of the plan. Nothing in the 1958 opinion lends

credence to the theory that this Court determined the

propriety of screening in 1958 when that was not in issue.

The matter of “ screening” had not been mentioned in the

opinion of Judge Lemley which preceded the 1958 appeal

(163 F. Supp. 13). Decisively, the record and opinions in

the 1956 trial and ensuing appeal—when the meaning of

the plan was in issue—contain not one mention of “ screen

ing” .

The conclusions of the Court below with regard to the

1955 plan were that: “One provision of the plan was to

permit any child who was assigned to a school wherein his

race was in the minority to transfer to a school wherein

his race was in a majority” (p. 14) ;eo and that “ It is

equally clear that student assignment (at that time called

“ screening” ) was provided for and permitted by the plan”

(p. 14). It is respectfully submitted that both quoted con

clusions rest upon nothing in the 1956 record, which indeed

conclusively demonstrates the contrary. The Board has

not documented them by any reference to the 1956 record.

As to the present pupil placement policies and proce

dures, there is also no conflict in the evidence, which is de

rived entirely from the records and testimony of the Board

and its employees. The Board has not followed the prac

tice of assigning all students without regard to racial con

siderations and on the basis of attendance areas. Indeed,

appellants do not understand that the Board even contends

that its present policies: (a) give pupils the “basic right”

60 References are to pages of the typewritten opinion below.

34

to attend the schools in their attendance areas; (b) re

strict students to their areas; or (c) disregard race in the

assignment of pupils. The evidence assembled in part III

of the Statement of the Case, supra, is overwhelmingly to

the contrary.

One or two examples are sufficient to demonstrate the

point. Documentary evidence makes it plain that the

Board’s preregistration announcement, which served as

the preliminary administrative step and ultimately de

termined most pupils’ initial assignments, makes express

reference to race and establishes optional registration

places based on race.61 The record is equally clear that only

Negro pupils wishing to attend formerly all white schools

were subjected to “ screening” to obtain initial assignment

in the area of their residence, and that no white child was

“ screened” when merely seeking initial assignment in his

attendance area.62 Further differences in the treatment

of Negro and white pupils during the initial assignment

and re-assignment stages are documented in detail in part

III of the Statement of the Case, supra. These differences

in treatment change the original plan for non-racial at

tendance area grouping.

In several ways the approval of the pupil placement prac

tices substantially impairs rights of Negro children pro

tected by the 1955 plan and the decree approving the plan.

The Board is now permitted to abandon policies, volun

tarily adopted and confirmed by judicial decree, which

guaranteed to all Negro students the eventual opportunity

to attend desegregated schools. The guarantee of complete

desegregation is replaced by a plan which does not guar

antee systematic elimination of segregation at any time.

The extent of desegregation now depends entirely upon

61 See note 37, supra.

62 See note 41, supra.

35

the will of the Board acting under a broad grant of dis

cretion. The pupil placement regulations do not even pro

hibit the use of race as an assignment standard; they merely

make no mention of race. While the regulations have oper

ated thus far to effect “ token” desegregation within the

overall segregated system, nothing in the regulations re

quires even this. Nothing in the pupil placement plan is

even inconsistent with a return to complete segregation.

Several opinions have pointed out that pupil placement

laws were not incompatible with continued segregation,

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 272 F. 2d 763, 766

(5th Cir. 1959); Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction,

277 F. 2d 370, 372 (5th Cir. 1960); Kelly v. Board of Edu

cation, 159 F. Supp. 272, 277 (M. D. Tenn. 1958).

The change from a plan which guaranteed eventual “ com

plete” desegregation to one which does not insure a sys

tematic approach to the elimination of discrimination is

now permitted after enforcement of Negro children’s con

stitutional right has been long delayed in deference to the