Hunter v. Underwood Joint Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hunter v. Underwood Joint Appendix, 1984. a1dcedaf-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/985534d4-16a8-40f4-847a-70a0479e3d16/hunter-v-underwood-joint-appendix. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

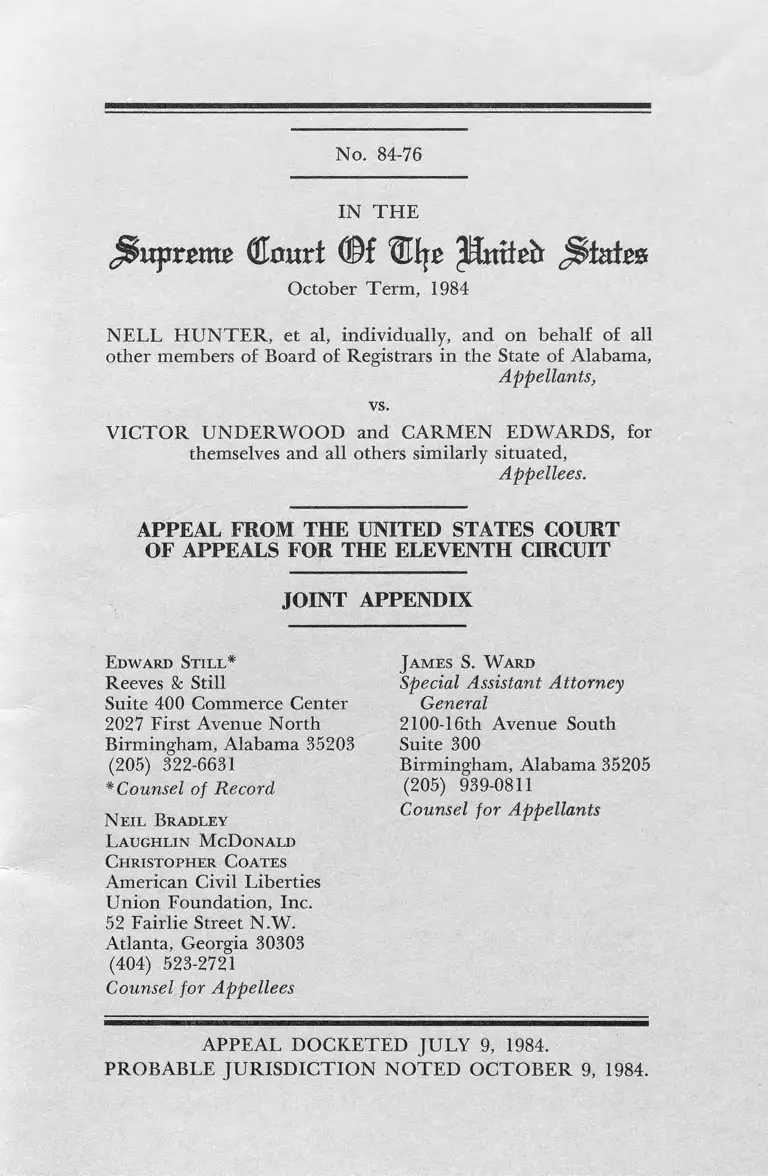

No. 84-76

IN T H E

jlispmus (SLonxi ©f Wc\t pmiefr jiia te

October Term , 1984

N ELL H U N T E R , et al, individually, and on behalf of all

other members of Board of Registrars in the State of Alabama,

Appellants,

vs.

V IC T O R UN D ERW O O D and CARM EN EDWARDS, for

themselves and all others similarly situated,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

JOINT APPENDIX

Edward St il l *

Reeves & Still

Suite 400 Commerce Center

2027 First Avenue N orth

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

(205) 322-6631

* Counsel of Record

N e il Bradley

L a u ghlin M cD onald

C h risto ph er C oates

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

52 Fairlie Street N.W .

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 523-2721

Counsel for Appellees

J am es S. W ard

Special Assistant Attorney

General

2100-16th Avenue South

Suite 300

Birmingham, Alabama 35205

(205) 939-0811

Counsel for Appellants

APPEAL DO CKETED JULY 9, 1984.

PROBABLE JU R ISD IC T IO N N O TED O C TO B ER 9, 1984.

1

TA BLE OF C O N TEN TS

Page

Com plaint ___________________________________________A-l

Answer ________________________________________—------ A-6

M otion to Amend A nsw er____ __l___1___________ __.. A-9

Judgment of U nited States District Court

for the Fifth Circuit, July 15, 1980 ___________ _-A l l

Excerpts from Testimony of J. Mills T hornton _________ A -l6

Excerpts from Deposition of J. Morgan Kousser __ r____ A-28

Certificate of Service ________________________________ A-33

Affidavit of Service ________________ ___________ ___ A-35

Opinion of the U nited States Court of Appeals

for the Eleventh Circuit, April 10, 1984, which

is the judgm ent in question, is printed in the

Appellants’ Jurisdictional Statement heretofore

filed, at Appendix A.

M emorandum Opinion of the U nited States District

Court for the N orthern District of Alabama,

August 11, 1978, a relevant opinion, is printed in

the Appellants’ Jurisdictional Statement heretofore

filed, at Appendix D.

M emorandum Opinion of the U nited States District

Court for the N orthern District of Alabama,

December 23, 1981, a relevant opinion, is printed

in the Appellants’ Jurisdictional Statement heretofore

filed, at Appendix E.

11

R E L E V A N T D O C K E T E N T R IE S

Com plaint filed ____________________________ _June 21, 1978

M otion of plaintiffs for preliminary

injunction filed _______ ____________________ June 21, 1978

On hearing on motion of plffs for preliminary injunction

before the Hon. Frank H. M cFadden — Oral m otion

of plffs to adm it Neil Bradley Pro Hac Vice —

Granted — Testimony of plaintiffs — Plffs rest — Oral

m otion of defts for directed verdict — R uling re

served — Testimony of defts — Defts rest — Rebuttal

testimony of plffs — Plffs rest — Argum ent of counsel

on m otion of deft to dismiss — All matters taken

under advisement __________________________ July 19, 1978

Clerk’s Court M inutes that m atter of preliminary in

junction is taken under advisement and m otion of

defts to dismiss is taken under advisement; written

findings of fact, conclusions of law and judgm ent

to be entered by the court —

filed and e n te re d ___________________________ July 19, 1978

M emorandum Opinion — filed and entered — August 11, 1978

O R D ER that plffs’ m otion for preliminary injunction

is overruled; further that defts’ motion to dismiss is

granted in part and causes of action num bered I,

II and III are dismissed; further that defts’ motion

for stay is granted; further that plffs’ m otion for ad

mission of additional exhibits is granted; ru ling on

the m otion to dismiss as to the fourth cause of action

is held in abeyance pending further briefs; any such

briefs should be subm itted w ithin 20 days of the

Date

date of this order — filed and e n te re d ______August 11, 1978

M emorandum opinion dated February 2, 1979

filed and entered _________ ____________ _. February 5, 1979

O RD ER dated February 2, 1979 in accordance with

the m em orandum opinion entered contemporaneously

Ill

that defendants’s m otion to dismiss is granted with

respect to plaintiffs’ fourth cause of action; further

that the other causes of action having been hereto

fore dismissed, the case is dismissed, with costs taxed

against the plaintiffs filed and entered ___ February 5, 1979

Notice of appeal of plaintiffs from the final

judgm ent entered on February 2,

1979 filed ______ _______________ _______ February 23, 1979

Transcript of proceedings had before the Honorable

Frank H. McFadden in Birmingham, Alabama on

July 19, 1978 filed _________________________ April 2, 1979

M otion of defendants for summary

judgment, filed _________________________October 15, 1979

Opposition of plffs to defendants’ m otion for

summary judgm ent, filed ______ 1________ October 19, 1979

M otion of plffs to certify the class action

allegation, filed ________________________October 25, 1979

Certified copy of judgment, USCA, issued as and for

the mandate on Oct. 29, 1979, that the judgm ent

of the District Court is VACATED in part and

REVERSED in part; and the same is REMANDED

to the District Court in accordance with the opinion

of Court; it is further ORDERED that the defts-

appellees pay to the plffs-appellants the costs on

appeal, to be taxed by the Clerk

of Court — f i le d _______________________ November 2, 1979

M otion of plffs for preliminary

injunction, filed __________________________January 5, 1980

Response of defendants to plff’s m otion for

preliminary injunction, filed ________ ........January 16, 1980

N O T IC E OF IN T E R L O C U T O R Y APPEAL given by

Plaintiffs from the denial de facto of the m otion for

preliminary injunction filed in this action on the

15th day of January, 1980 — filed ________ February 7, 1980

Date

IV

M emorandum Opinion, filed _____________February 14, 1980

O R D ER in accordance with the M emorandum

Opinion entered contemporaneously that plffs’

m otion for preliminary injunction is OVER

RULED, filed; entered 02-14-80 _______February 14, 1980

Certified copy of O R D ER from U. S. Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit that the m otion of appellants

for an injunction pending appeal is DENIED, filed,

filed February 19, 1980 ______ __________ .March 28, 1980

O R D ER dated April 17, 1980, that Counts one, two

and three of the com plaint are dismissed in accord

ance with the M emorandum Opinion entered by the

Court August 11, 1978—further that the rem aining

Count in this action, Count four, be m aintained by

plffs as a class action on behalf of persons as set out

in this order—further that the suit may be m aintained

against the defts as a class representing all members

of the sixty-seven county boards of registrars in the

State of Alabama, filed; entered 04-18-80 ____April 18, 1980

Certified copy of judgment, U. S. Court of Appeals,

dated July 15, 1980, and issued as mandate Septem

ber 11, 1980, affirming the order of the District

Court and ordering that plaintiffs-appellants pay to

defendants-appellees the costs on appeal to be taxed

by the Clerk, USCA, with certified copy of opinion,

bill of costs, original record and two supplemental

records attached (Kravitch, Henderson and Reavley,

Circuit Judges) — filed ______________ September 15, 1980

M otion of the plffs for leave to amend the complaint

with am endm ent thereon, filed — 05-15-81

GRAN TED; Entered 05-15-81 _____________ April 24, 1981

ANSW ER of the defts to the complaint, filed ___ May 6, 1981

M otion of the defts to dismiss or in the alternative,

M otion to strike plffs’ m otion to amend complaint

Date

V

Date

by adding a fifth cause of action, filed —

05-15-81 OVERRULED; Entered 05-15-81 _____May 8, 1981

Request of the plffs for admission by the defts with

exhibits attached, f i le d ___________ ___ ____ May 12, 1981

M otion of the defts to dismiss fifth cause of

action, filed ____ _____________ _____ _______-_June 5, 1981

O R D ER ON PR E-TR IA L H EA RIN G held May 11,

1981, dated July 2, 1981, that Joseph J. Trucks is

DISMISSED as pty deft, filed;

Entered 07-08-81 ____________________________ July 6, 1981

On trial before the Hon. Frank H. McFadden —

Argument of counsel on m otion of defendants for

summary judgment — oral order overruling motion

of defendant for summary judgm ent for failure to

exhaust administrative remedies and holding motion

of defendant to dismiss fifth cause of action in avey-

ance entered — M otion of defendants to amend

answer to fourth cause of action filed — Oral order

granting m otion to amend answer entered — Evidence

of plaintiffs presented (no testimony) —- Plaintiffs

rest — Oral m otion — Oral motion of defendants to

dismiss — R uling reserved — Testimony of defend

ants — Defendants rest — Taken

under advisement ________________ ________-Ju ly 21, 1981

Clerk’s Court M inutes dated July 21, 1981 that this

case is taken under advisement; w ritten findings of

fact, conclusions of law and judgm ent to be entered

by the court; filed; Entered 07-22-81 ______ _-Ju ly 22, 1981

ORD ER (N O T IC E OF A C TIO N RAISING T H E

QU ESTIO N OF C O N ST IT U T IO N A L IT Y OF A

ST A T U T E OF T H E U N IT E D STATES) that pur

suant to 28:2403 the court certified the Attorney

General that there is drawn in question in this case

the constitutionality of the Act of June 25, 1868,

ch. 70, 15 Stat. 73, filed; Entered 07-29-81 ____July 29, 1981

VI

M emorandum Opinion filed;

entered 12/23/81 _____________________December 23, 1981

O R D ER in accordance with the m em orandum of

opinion that judgm ent is granted in favor of the

defendants and that the complaint is DISMISSED;

costs taxed to the plaintiffs, filed;

entered 12/23/81 ------------------------------- December 23, 1981

Notice of appeal of plffs from the final judgm ent

entered on 4/18/80 and

12/23/81 filed _______ _____________ _ December 29, 1981

Date

A-l

IN T H E U N IT E D STATES D IST R IC T C O U R T

FO R T H E N O R T H E R N D IS T R IC T OF ALABAMA

SO U TH ER N DIVISION

V IC T O R UN DERW OOD and )

CARM EN EDWARDS, for them- )

selves and all others similarly )

situated )

)

PLA IN TIFFS, )

)

vs. )

)

N ELL H U N T E R , JOSEPH J. )

TRUCKS, individually and as mem- )

bers of the Board of Registrars of )

Jefferson Co., and TH O M A S A. )

JER N IG N A N , CLARICE B. )

ALLEN, CLEO F. CHAMBERS, )

individually and as members of )

the Board of Registrars of Mont- )

gomery Co., on behalf of all other )

members of Boards of Registrars )

in the State of Alabama )

)

DEFENDANTS. )

CA78 M0704S

CO M PLA IN T

1. This action arises under the First, Fifth, T hirteenth ,

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of the Constitution of

the U nited States and 42 U.S.C. §§1971, 1973, 1981 and 1983.

Jurisdiction is vested in this Court by 28 U.S.C. §§1331 (a ) ,

1343 (3) and (4), and 2201. T he m atter in controversy ex

ceeds, exclusive of interests and costs, the sum of ten thousand

dollars. This is an action for appropriate equitable relief and

declaratory judgm ent of the unconstitutionality of Ala. Const.,

Art. VIII, §182 (1901) , to the extent that it disqualifies from

A-2

being registered or voting persons convicted of certain offenses,

and to prevent deprivation under color of state law, statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom or usage of rights, privileges and

imm unities secured to plaintiff, including the rights to due

process, equal protection, and the unabridged participation in

the electoral process protected by the First, Fifth, T hirteenth ,

Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments of the Constitution of

the U nited States and by T itle 42 of the U nited States Code,

§§1971, 1973, 1981 and 1983.

2. Plaintiff Victor Underwood is a white citizen of Ala

bama, over the age of 21 years, and a resident of Jefferson

County.

3. P laintiff Carmen Edwards is a black citizen of Alabama,

over the age of 19 years, and a resident of Montgomery County.

4. Defendants Nell H un ter and Joseph J. Trucks are mem

bers of the Board of Registrars of Jefferson County. T here is

presently a vacancy on said board. Defendants Thom as A.

Jernignan, Clarice B. Allen, and Cleo F. Chambers are mem

bers of the Board of Registrars of Montgomery County. All

defendants are sued individually and in their official capaci

ties as members of the Boards of Registrars, and as representa

tives of the class of all members of the Boards of Registrars of

the counties of the State of Alabama.

5. Attorney General W illiam Baxley shall be served a copy

of this complaint so that he may defend the constitutionality

of the State Constitution provision challenged herein. 28

U.S.C. §2403 (b ); Ala. Code, §6-6-227 (1975).

6. T he plaintiffs bring this action on their own behalf and

on behalf of all others similarly situated and against the de

fendants in their official capacities, as individuals and as rep

resentatives of their class pursuant to Rule 23 of the F.R.Civ.P.

T he plaintiffs’ class includes all persons disqualified from be

ing registered or voting by operation of Ala. Const., Art. VIII,

§182 (1901) . T he defendants’ class includes members of

boards of registrars of Alabama. T he prerequisites of subsec

tions (a) and (b) (2) of Rule 23 are satisfied. T here are

common questions of law and fact affecting the several rights

A-3

of citizens to register and to vote. T he members of the classes

are so numerous as to make it impracticable to bring them all

before this Court. T he claims or defenses of the parties are

typical of the claims or defenses of the classes as a whole. A

common relief is sought. T he interests of each class are ade

quately represented by the named parties, and the parties op

posing each class have acted or refused to act on grounds gen

erally applicable to the class, thereby m aking appropriate final

injunctive and declaratory relief with respect to the class as a

whole.

7. Ala. Const., Art. V III, §182 (1901) , disenfranchises per

sons who have been convicted of certain named offenses, any

crime punishable by im prisonm ent in the penitentiary, or any

infamous crime or crime involving moral turpitude. Because

any crim e carrying a maximum penalty of more than one year

is “punishable by imprisonm ent in the penitentiary,” only cer

tain offenses carrying a penalty of 12 m onths or less, or a fine

(hereinafter referred to as misdemeanors and m inor felonies)

are disenfranchising offenses, namely, the ones listed in §182

and those “involving moral turpitude."

8. Victor Underwood was a duly qualified and registered

voter in Jefferson County. Because of a conviction for issuing

a worthless check, his name was purged from the registration

rolls by the Jefferson County Board of Registrars. Carmen

Edwards is otherwise qualified to register to vote in Montgom

ery County bu t has been denied registration by the Montgom

ery County Board of Registrars because of her conviction for

issuing a worthless check, an offense which is considered to be

a “crime involving moral tu rp itude.”

9. There is between the parties an actual controversy as

herein set forth. T he plaintiffs and others similarly situated

and affected on whose behalf this suit is brought suffer irrep

arable injury by reason of the acts herein complained of. Plain

tiffs have no plain, adequate or complete remedy to redress the

wrongs and unlawful acts herein complained of other than this

action for a declaration of rights and an injunction. Any rem

edy to which plaintiffs and those similarly situated could be

A-4

rem itted would be attended with such uncertainties and delays

as to deny substantial relief, would involve m ultiplicity of suits

and cause them further irreparable injury, damage and incon

venience.

FIR ST CAUSE OF A C TIO N

10. T he misdemeanors and m inor felonies listed in §182 as

disenfranchising offenses unconstitutionally impinge upon the

franchise because they deny the franchise without a compelling

state interest in violation of the First, Fifth, and Fourteenth

Amendments of the Constitution of the U nited States.

SECOND CAUSE OF A C TIO N

11. T he misdemeanors and m inor felonies listed in §182 as

disenfranchising offenses deny plaintiffs and the class they rep

resent the equal protection of the laws as guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Am endment of the Constitution of the U nited

States because more serious offenses are not disabling.

T H IR D CAUSE OF A C TIO N

12. Disfranchisement for conviction of a “crime involving

moral tu rp itude” is based on a definition that is vague and in

definite and denies plaintiffs and the class they represent the

right to register and to vote in violation of the First, Fifth, and

Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution of the U nited

States.

F O U R T H CAUSE OF A CTIO N

13. T he list contained in §182 was specifically adopted be

cause of its supposed disproportionate impact on blacks, with

the in tent to disfranchise blacks.

14. T he disfranchising provisions of §182 abridge the right

to vote on the basis of race, in violation of the First, Fifth,

T hirteenth , Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of the

Constitution of the U nited States, and 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and

1983.

A-5

RELIEF

W H ER EFO RE, Plaintiffs respectfully pray that this Court

will take jurisdiction of this cause and do the following:

A. Find that the named plaintiffs and defendants are ade

quate representatives of their respective classes and allow this

cause to proceed as a class action;

B. G rant the plaintiffs a prelim inary injunction, to be made

perm anent later, requiring that they and the class they repre

sent be restored to the rolls of those registered to vote or be

allowed to register without regard to Ala. Const., Art. VIII,

§182 (1901);

C. Declare Ala. Const., Art. VIII, §182 (1901), to be un

constitutional insofar as it applies to offenses carrying a penalty

of one year or less, and enjoin its further application;

D. G rant the plaintiffs their costs and reasonable attorneys’

fees and expenses.

Subm itted by,

/ s / E dward St il l

Edward Still

601 T itle Building

Birmingham, AL 35203

205/322-1694

Of Counsel

Laughlin McDonald

Neil Bradley

Christopher Coates

52 Fairlie Street, NW

Atlanta, GA 30303

A-6

IN T H E U N IT E D STATES D IS T R IC T C O U R T

FO R T H E N O R T H E R N D IST R IC T OF ALABAMA

SO U TH ER N DIVISION

V IC T O R U N DERW OO D and )

CARMEN EDWARDS, for them- )

selves and all others similarly )

situated )

>

Plaintiffs )

)

v ) CASE NO.

) CA 78 MO 704S

N ELL H U N T E R , JOSEPH J. )

TRUCKS, individually and as )

members of the Board of Registrars )

of Jefferson Co., and TH O M A S A. )

JERN IG A N , CLARICE B. )

ALLEN, CLEO F. CHAMBERS, )

individually and as members of the )

Board of Registrars of Montgomery )

Co., on behalf of all other members )

of Board of Registrars in the State )

of Alabama )

)

Defendants )

ANSWER.

Come now the Defendants in the above captioned case and

for answer to Fourth Cause of Action in the Com plaint say as

follows:

F O U R T H CAUSE OF A CTION

1. Defendants deny all the averments and allegations con

tained in paragraph 13 of the Fourth Cause of Action.

2. Defendants deny all the averments and allegations con

tained in paragraph 14 of the Fourth Cause of Action.

A-7

3. Defendants deny that the Plaintiffs are entitled to any

relief.

AFFIRM A TIV E DEFENSES

1. For that the Fourth Cause of Action fails to state a claim

or cause of action against the Defendants upon which relief

can be granted.

2. For that the State of Alabama may constitutionally ex

clude from the franchise felons or individuals who have com

m itted crimes involving moral turpitude.

3. For that the State of Alabama has a compelling state in

terest in excluding from the franchise felons or those indi

viduals who have been convicted of crimes involving moral

turpitude.

4. For that the disinfranchisement of those convicted of fel

onies or crimes involving moral turpitude bears a rational re

lationship to the achieving of a legitimate state interest.

5. Based on an opinion rendered by the Attorney General

of the State of Alabama which holds that conviction of a m u

nicipal ordinance will not disqualify a person from voting even

if such conviction would constitute a crime involving moral

tu rp itude if prosecuted under state law, the Plaintiffs have no

standing to bring this action or to serve as class representatives.

Respectfully submitted

/s/ J am es S. W ard

James S. W ard

Special Assistant Attorney General

for Defendants

1933 Montgomery Highway

Birmingham, Alabama 35209

939-0275

C E R TIFIC A T E OF SERVICE

I certify that I have served a copy of the above and fore

going Answer upon the Honorable Edward Still, Commerce

A-8

Center, Suite 400, 2027 1st Avenue North, Birmingham, Ala

bama 35203, by placing a copy of same in the U nited States

mail, postage prepaid and properly addressed on the 6 day of

May, 1981.

,/s/ J am es S. W ard

Of Counsel

A-9

IN T H E U N IT E D STATES D IS T R IC T C O U R T

FO R T H E N O R T H E R N D IST R IC T OF ALABAMA

SO U TH ER N DIVISION

V IC T O R UN DERW OO D and )

CARM EN EDWARDS, for them- )

selves, et al )

)

Plaintiffs )

)

v ) CA 78-M-0704

)

NELL H U N T E R , et al )

)

Defendants )

M O TIO N T O AMEND ANSW ER

Come now the Defendants in the above styled cause, by and

through their attorney of record, and respectfully move this

Court for an O rder allowing Defendants to amend the answer

previously filed by them to Plaintiffs’ Fourth Cause of Action

by adding the following affirmative defenses:

1. For that the Plaintiffs have failed to exhaust available

and existing state or city administrative remedies which would

restore to them the right to vote.

Respectfully submitted

Stuart & W ard

/s/ J am es S. W ard

Special Assistant Attorney General

for Defendants

1933 Montgomery Highway

Birmingham, Alabama 35209

939-0276

A-10

C E R T IFIC A T E OF SERVICE

I certify that I have served a copy of the above and fore

going M otion to Amend Answer upon the Honorable Edward

Still, by hand delivering a copy of same to him in open Court

on this the 21 day of July, 1981.

/s/ J am es S. W ard

Of Counsel

A -ll

U N IT E D STATES C O U R T OF APPEALS

FO R T H E F IF T H C IR C U IT

October Term , 19

No. 80-7084

D. C. Docket No. CA 78-M-704-S

V IC T O R UNDERW OO D, and CARMEN EDWARDS,

for themselves and all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

N ELL H U N T E R , JOSEPH J. TRUCKS, Individually

and as members of the Board of Registrars

of Jefferson County, E T AL.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the U nited States District Court for the

N orthern District of Alabama

Before KRAV ITCH, HENDERSON and REAVLEY, Circuit

Judges.

JU D G M EN T

This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of the rec

ord from the U nited States District Court for the Northern-

District of Alabama, and was argued by counsel;

ON CO N SID ERA TIO N W HEREOF, It is now here o r

dered and adjudged by this Court that the order of the District

Court appealed from, in this cause be, and the same is hereby,

affirmed;

IT IS FU R T H E R ORDERED that plaintiffs-appellants pay

to defendants-appellees, the costs on appeal to be taxed by the

Clerk of this Court.

JULY 15, 1980

ISSUED AS M ANDATE: SEP 11 1980

A-12

IN T H E U N IT E D STATES C O U R T OF APPEALS

FO R T H E F IF T H C IR C U IT

No, 80-7084

V IC T O R UN DERW OOD, and CARMEN EDWARDS,

for themselves and all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

N ELL H U N T E R , JOSEPH J. TRUCKS, individually

and as members of the Board of Registrars of

Jefferson County, Et Al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the U nited States District Court for

the N orthern District of Alabama

(JULY 15, 1980)

Before KRAV ITCH, HENDERSON and REAVLEY, Circuit

Judges.

PER CURIAM :

Plaintiffs appeal the denial of their preliminary injunction

attacking the constitutionality of the Alabama Constitution,

Art. V III, § 182 (1901), as it operates to disenfranchise them.

We affirm.

Procedural History

T he confusing route through which this case reached this

court for the second time requires a brief digression. On June

21, 1978, plaintiffs filed a complaint seeking a declaratory judg

m ent that § 182 is unconstitutional. Plaintiffs asserted four

grounds for relief: (1) that the misdemeanors and m inor fel

onies listed in § 182 as disenfranchising offenses unconstitu

tionally impinge upon the franchise because they deny the

franchise without a compelling state interest in violation of the

First, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments; (2) that the disen

franchising offenses deny plaintiffs the equal protection of the

A-13

laws because more serious offenses are not disabling; (3) that

disenfranchisement for conviction of a “crime involving moral

tu rp itude” is based on a definition that is unconstitutionally

vague; and (4) that the list of offenses was specifically adopted

with the intent to disenfranchise blacks and, in fact, abridges

the right to vote on the basis of race. Defendants moved to

dismiss the complaint for failure to state a claim upon which

relief could be granted.

Plaintiffs also sought a preliminary injunction restoring

them to the voting rolls which was premised on the first three

causes of action, bu t not the fourth. On July 19, 1978 the court

conducted a hearing on the preliminary injunction, bu t subse

quently expanded it to include arguments on the m otion to

dismiss and was presented with evidence outside the pleadings.

T he court denied the preliminary injunction and granted the

m otion to dismiss on August 11, 1978 with respect to the first

three causes of action, stating that “if the motion to dismiss is

treated as motion for summary judgm ent under Rule 56, it is

due to be granted with respect to the first three causes of ac

tion.” This court reversed because the district court failed to

comply with F.R.Civ.P. 56 by providing a 10-day notice period

required when a motion to dismiss is treated as a m otion for

summary judgm ent. Underwood v. H unter, 604 F.2d 307 (5th

Cir. 1979).

T he district court had also denied the fourth cause of action

as failing to state a claim upon which relief could be granted.

This court reversed, stating that plaintiffs’ allegations, if sup

ported by facts developed in a later proceeding, did state a

claim. Id.

On remand, plaintiffs again moved for a preliminary injunc

tion in the district court, which was denied in a memorandum

opinion on February' 14, 1980.1 T he present case is plaintiffs’

appeal from that order.

iO n A pril 18, 1980, the tria l court again reviewed p lain tiffs’ first three

causes of action, and again dismissed on the basis of its August 11, 1978

m em orandum opinion. W ith respect to count four, the court gran ted

p lain tiffs’ m otion for class certification w ith regard to both p la in tiff and

defendant classes.

A-14

Merits

A prelim inary injunction is an extraordinary remedy and its

denial will be overturned only for an abuse of discretion.

Compact Van Equipm ent Co. v. Leggett & Platt, Inc., 566 F.2d

952 (5th Cir. 1978) . T o be entitled to a preliminary injunc

tion, a movant must establish each of four prerequisites: (1) a

substantial likelihood of ultimately prevailing on the merits;

(2) a showing of irreparable injury unless the injunction is

sues; (3) proof that the threatened injury to the movant ou t

weighs whatever damage the proposed injunction may cause

the opposing party; and (4) a showing that the injunction, if

issued, would not be adverse to the public interest. Id.;

Comerisch v. University of Texas, 616 F.2d 127, 130 (5th Cir.

1980).

Plaintiffs fail to meet the second element, a showing of ir

reparable harm. Although each had been disenfranchised for

conviction of a crime involving moral turpitude, an individual

in Alabama can have his right to vote restored if pardoned.

ALA. CODE § 12-14-15, see § 17-3-5. Victor Underwood was

purged from the voting list in Jefferson County on April 30,

1977 for conviction for issuing a worthless check 2.\/2 to 3 years

prior to the July 19, 1978 hearing on the initial preliminary

injunction. Although officials of the Jefferson County Board

of Registrars informed Underwood of the procedure for having

his voting rights restored, he has made no effort to comply, nor

has he alleged any difficulty in complying with this procedure.

Carmen Edwards was purged from the voting list of Montgom

ery County pursuant to her conviction for the crime of issuing

a worthless check in May 1978. Although she attem pted to re

ceive a pardon, for purposes of restoration of her voting rights,

from the Mayor of Montgomery, she was told that she must

wait at least a year. She has not sought a pardon since the wait

ing period has elapsed.

N either plaintiff, then, has presented any evidence which in

dicates that a proper application for a pardon would not have

been granted. Under these circumstances, we cannot find that

A-15

granting a m otion for a prelim inary injunction is either neces

sary or appropriate. By affirm ing the district court’s denial of

a prelim inary injunction, we intim ate no view as to the merits

of plaintiffs’ allegation attacking the constitutionality of § 182

of the Alabama Constitution.

AFFIRMED.

A-16

DR. J. MILLS T H O R N T O N ,

[49] having been first duly sworn, was examined and testified

as follows:

Q. Dr. Thorn ton , what do you teach and where?

A. I teach the History of the South at the University of Mich

igan in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Q. In addition to the resume which has been received as De

fendant’s Exhibit 16, have you conducted your own research

into the history of the south around the period of time 1901?

[50] A. Yes, I have.

Q. And what has that research consisted of, please, sir?

A. Well, I have worked in the post-bellum period generally

on a num ber of research projects, bu t in particular the Con

stitutional Convention of 1901. I did a thesis as an undergrad

uate centering on the origins of disfranchisement in Alabama.

Q. And that was your Ph.D.?

A. No, that was not, that was a B.A. thesis.

Q. B.A.?

A. Yes.

Q. W here was that?

A. At Princeton University.

Q. Based on your reading and your research and your educa

tion that you received, are you fam iliar with the period of time

up to and including the Convention of 1901 in this State?

A. Yes, I am.

Q. And are you fam iliar with the Constitutional Convention

of 1901?

A. Yes, I am.

Q. And I will ask you, Dr. T hornton, in your opinion, is

it necessary in talking about the 1901 Convention to examine

it and look at it as a whole as opposed to any pieces?

[51] A. Yes, absolutely.

Q. And is it necessary then, in order to determine what the

in tent of the drafters of Section 182 might have been, to exam

ine the Convention as a whole and the suffrage article which

was passed as a whole?

A. Yes.

A-17

MR. STILL: Objection, leading.

T H E C O U R T: Overruled.

Q. (By Mr. Ward) Doctor, what, in your opinion, is the pur

pose or was the purpose of the Alabama Constitutional Con

vention of 1901?

A. T he Alabama Constitutional Convention of 1901 was

called to prevent a recrudescence of the Populist Revolt which

had convulsed Alabama politics throughout the 1890’s,

throughout the period of 1890 and the Spanish American War.

It was intended to lim it the franchise in Alabama in such a way

that it would be impossible for the rule of the Democratic

Party, the hegemony of the Democratic Party in the State again

to be effectively challenged.

Q. W hat are you saying then, Dr. T hornton, is there were

political reasons for calling the Convention?

A. T h a t is correct.

Q. And was the eventual passage of 182 part of this purpose

or this scheme, this political scheme?

A. Yes, it was.

[52] Q. Doctor, what if anything did the Convention do in

order to accomplish this purpose? W hat did they pass, if any

thing?

A. Well, there are two halves of the scheme, as you would call

it. T he first is the Suffrage Article, and the second is the a rti

cle apportioning the State Legislature. But the Suffrage Article

is the primary element in the effort to structure Alabama poli

tics the way they wished.

Q. Could you explain to the Court, please, sir, what even

tually passed as you were calling the Suffrage Article? If I un

derstand, there is a perm anent part and a temporary part. If

you could explain that to the Court, please, sir.

A. All right. T he Suffrage Article as it finally comes from

the Convention has several parts to it. T here is a set of re

quirem ents that are applicable from the beginning on all

voters. Those include residency requirements, two years in the

State and one year in the county and six months in the pre

cinct, a poll tax and the crimes section, which is at issue here.

A-18

T hen in addition to those requirem ents which take effect from

the ratification and proclamation of the Constitution, there

are two separate suffrage plans known as the temporary plan

and the perm anent plan. U nder the temporary plan which was

in effect un til January 1st of 1903, that is for a year and one

m onth because the Constitution was proclaimed in effect at the

end of November [53] of 1901, so for the m onth of December of

1901 and then the calendar year 1902, the temporary plan is in

effect. U nder the temporary plan, all persons, all adult males

who can meet the residency requirem ent and the crimes dis

franchisement requirem ent may register, if they have served

honorably in the armed forces, in the armed forces in any

war — I started to say the armed forces of the U nited States,

bu t it is not just the armed forces of the U nited States, because

it includes the Confederate Army as well. So the armed forces

in any of the wars of the U nited States, or if they are direct

descendants of any person who did so, or if they are of good

character and understand the obligation and duties of a citizen.

T h a t temporary plan goes out of effect on January 1st, 1903,

and the perm anent plan comes into operation. U nder the per

m anent plan, any person may register who is an adult male

meeting the other requirem ents, and who either can read and

write the English language and has been employed for 12

months preceding the time he offers to register, or who owns

40 acres of land on which he resides, or owns an am ount of

either real estate or personal property assessed for taxes at $300

on which the taxes have been paid.

Q. Dr. T hornton, was the poll tax part of the suffrage plan

that was passed?

A. T he poll tax is a part of the suffrage plan that is enacted.

On the other hand, the poll tax is not an element in registra

tion. T he poll tax is an element in voting.

# # # #

[54] Q. Did Section 182, which is the crime provision, apply

to those people who were to be registered under the temporary

plan?

A-19

A. Yes, it did, just as does residency.

Q. Any others?

A. It would be residency and crimes, and then that you be

over the age of 21 and a male.

# # # #

[56] Q. Dr. Thorn ton , based on your study and your research

and your reading, in your opinion, I will ask you whether [57]

or not disfranchisement of poor whites was an im portant — as

im portant intention and motive of the delegates to the Conven

tion of 1901 as was the disfranchisement of blacks?

A. Absolutely. T he two halves of the threat that Populism

has posed during the 1890’s are that poor whites have left the

Democratic Party and thus have made general elections m atter

in the State politics, and that they are appealing to black voters

and turning black voters into the balance of power. Conse

quently, the way to prevent a recrudescence of Populism must

involve dealing with the threat on both levels. Both in elim i

nating the black vote that had — the courting of which had

represented the principal threat from the point of view of con

servative white democrats, and the elim ination of poor white

voters who had been the backbone of the Populist Party, the

members of the Farm er’s Alliance and the people who had

bolted the Democratic Party in the first place.

Q. W ould it be fair to say, in your opinion, that Section 182

was part of the plan to prevent and disfranchise the poor whites

as well as any blacks?

A. Yes, that’s right. T he entire Suffrage Article has that aim

in Section 182, as much as other sections.

Q. Doctor, can we then look at some things that you have

brought in support of that opinion? Can you tell the Court

who John Knox was, very briefly?

[58] A. John Knox was the President of the 1901 Convention,

a lawyer from Anniston.

Q. Did he make any statement a few years after the Conven

tion of 1901 concerning what the motives of the people there

were?

A-20

A. Yes. In 1905, he wrote an article for Outlook Magazine.

Outlook was a national magazine comparable to T im e or News

week today, describing the motives of the delegates to the Con

vention of 1901.

# # # #

[59] Q. (By Mr. W ard) I will ask you, Dr. Thorn ton , in read

ing that article, what, if anything, John Knox said concerning

the intention of the delegates of the 1901 Convention.

A. Well, he makes the point that whereas he concedes that

the temporary plan has on its face the in tention of enfranchis

ing whites and not blacks, he makes the point that that is the

only possible way that the Constitution could have been rati

fied. They had to get it past the voters. But he says the p rin

cipal goal of the delegates was to place the Suffrage, as he says,

on a high plane, and that they lim ited the time of the applica

tion of the temporary plan quite severely to one year, 13

months, and that as soon as the perm anent plan went into

effect, that it would apply across the board to the standard

phrase from the Convention, from the delegates as to all the

ignorant and the vicious.

Q. And that was referring to the whites?

[60] A. T h a t refers to blacks and whites.

Q. In speaking of the efforts to extend the temporary plan,

what, in your studies, does the leadership of the Democratic

Convention — what was their intention along those lines, along

the extension of the temporary plan beyond January 1, 1903?

A. W ell, there are repeated — let me say this. T here are es

sentially three points of view among the delegates about Suff

rage, or three blocs. This is excluding Republican and Popu

list delegates who are opposed to disfranchisement of any kind.

But among the democratic delegates, there are those who favor

an immediate conversion to a plan which would disfranchise

poor whites and blacks equally and confine the electorate at

once to literate whites. This is a small m inority among the

delegates. T h e ir amendment, in fact, when the test vote comes,

their am endm ent is rejected 109 to 24, I believe is the vote.

A-21

T hen there are delegates chiefly from rural N orth Alabama

counties who are in favor of enfranchising all whites and dis

franchising all blacks, and then there are the delegates who

are actually the majority of the Democratic Party and who con

stitute the leadership of the Convention, who favor the dis

franchisement of poor whites, bu t believe that they cannot get

the Constitution ratified unless they have in something like

the temporary plan, which [61] will leave white voters in the

N orth Alabama counties to vote in favor of ratification. Now

these, this group is defined as a majority of the Convention by

a series of efforts on the part of this group that likes the tempo

rary plan and doesn’t like the perm anent plan, because the per

m anent plan would disfranchise poor whites who want to ex

tend the time of operation of the temporary plan. T here are

no less than three efforts made during the course of the Con

vention to extend the time of the temporary plan. First to Jan

uary 1st, 1906, which is beaten back; then to January 1st, 1905,

which is beaten back, and then to allow persons who might be

come 21 by January 1st, 1905 to register under the temporary'

plan before January 1st, 1903, even though they were not yet

21, bu t to begin voting when they did become 21. All three of

those efforts are beaten back, and those roll call votes define

who in the Convention is in favor of the temporary plan as an

expedient to get the Constitution ratified and who are much

more committed to black disfranchisement and the enfran

chisement of all whites.

Q. T hen I will ask you whether or not the efforts to defeat

the extension of the temporary plan is a factor, in your opin

ion, that the delegates of the Convention were just as con

cerned about disfranchising poor whites as they were blacks?

A. Yes, that’s correct.

* # # #

[62] Q. And if I may, to read you this and to state if that is

your understanding according to McMillan, “In 1905 Francis

G. Caffee, a lawyer who was practicing in Montgomery at the

time of the Alabama Convention, wrote concerning its motives:

A-22

‘It was generally wished by leaders in Alabama to disfranchise

many unworthy white men, to rid the State eventually, so far

as could possibly be done by law, of the corrupt and ignorant

among its electorate, white as well as blacks. T he poll tax and

vagrancy clauses were pu t into the Constitution.’ ” Is that the

reference and quotation to which you refer?

A, Yes.

# * * #

[63] Q. (By Mr. W ard) Dr. T hornton, I believe before you

testified, did you not, that Section 182 of the Constitution, the

crimes provision and the property qualifications and the poll

tax, applied as well to those who registered under the tempo

rary plan?

A. T h a t’s right, both temporary and permanent.

Q. I will ask you whether or not, in your opinion, that would

be another factor in your statement that the intention of the

framers and the people at the Convention of 1901 was to dis

franchise poor whites as well as blacks?

A. Yes. In fact, in the debates at the Convention when there

are allegations that all whites, including as they say, “vicious

whites” will be perm itted to register under the temporary plan,

since it would be essentially impossible for any white man not

to be able to register under the temporary plan, the principal

reliance that the delegates in the majority on the Suffrage Com

m ittee who were defending the Suffrage Committee plan, the

principal reliance that they have in defense of themselves is the

crimes provision. They say, “No, it is not true that the really

vicious whites will be perm itted to register under the tempo

rary plan because they will, if they had been convicted of

crime, they will go out under Section 182.”

# # #

[68] Q. Was 182 discussed very much, Section 182?

A. No.

## # #

A-23

[69] Q. T he Constitution of 1875, Dr. T hornton, already pro

vided that those who were convicted of a crime which resulted

in imprisonm ent in the penitentiary would be disfranchised?

A. T h a t’s correct.

Q. And do you know of the crimes added to Section 182, if

those, what the majority of those crimes were?

A. Well, the Crimes Article is another example of the way in

which public relations is being used to convince the electorate,

the white electorate that it is not voting to disfranchise itself

bu t is voting for a constitution directed explicitly at blacks.

Because as you say, the Constitution of 1875 already disfran

chises anyone who is convicted of a crime for which you might

be sentenced to the penitentiary. W hat the Constitution of

1901 does is repeats that same phrase, bu t before it gets to that

phrase, [70] it goes through a long list of crimes for which you

can be sentenced to the penitentiary. Now all of those are in

cluded in the general phrase, and you could simply have re

peated the general phrase, bu t these crimes are pu t in precisely

because they are associated in the public m ind with the be

havior of blacks. They are drawn by the Suffrage Committee

from a report by a delegate from Dallas County who is named

John Fielding Burns, who had drawn them up precisely be

cause they were crimes which, in his practice as a Justice of the

Peace, he had found to be — he had found blacks to be, as he

thought, peculiarly subject to. But the Suffrage Committee

takes them and puts them into the Article not with any real

effect as it were, because the general clause incorporates them,

but rather as a public relations gesture so that the white elec

torate, as they read this list, will have their m ind focused on

this as an anti-Negro measure.

Q. W hen in fact, if I understand you, the Constitution of

1875, in effect, already had provided the same thing?

A. T h a t’s correct.

Q. Doctor, have you researched between the time of the Con

stitution of 1901, which became effective —

A. W hich was in December of 1-901, that’s right, end of No

vember.

A-24

Q. — until the end of the temporary plan, which was [71] De

cember 31st, 1902?

A. Correct.

Q. W hat percentage of whites were disfranchised with Sec

tion 182 and what percentage of blacks were disfranchised?

A. W ell, give me two seconds and I can give you the figures

on that.

On the census of 1900, there are 229,766 adult white males

in the State, and 181,345 adult black males. We know the

num ber of persons who were registered as a January 1st, 1903,

which —

Q. By looking at the census figures and all the information,

did you arrive at a percentage of whites and blacks disfran

chised between December 1901 and December of 1902?

A. Well, it would appear that 178,365 blacks and 35,294

whites were disfranchised by the operation of the temporary

plan.

Q. W hat percentage of those, then, white to black, were be

cause of Section 182? I believe you told me some percentages

before.

A. Yes. It would appear that possibly — these are extrapolat

ing from figures as to those who have committed crimes taken

from the biannual reports taken from the Board of Convict

Inspectors. It would appear that about 3 percent of whites who

were disfranchised because [72] of the operation of the crimes

clause, and about seven and a half percent of blacks who were

disfranchised were disfranchised because of the operation of the

crimes clause.

* * * *

Q. (By Mr. W ard) Dr. T hornton, one or two last quick ques

tions. In your opinion, I will ask you whether or not the poll

tax, which was passed in the 1901 Convention, had the effect

of disfranchising more whites than blacks?

A. Absolutely, because disfranchisement by the poll tax has

to take place after you are registered. And since so few blacks

were registered and since you have to be a registered voter be

A-25

cause you can be disfranchised would have operated almost ex

clusively on the whites.

Q. And that was part of the scheme, to disfranchise poor

whites as well as blacks?

A. T h a t’s right, it was so understood at the time. On this, I

m ight say, as far as I know, there are no scholars who disagree.

# # # #

[73] Q. T he aim of the 1901 Constitution Convention was to

prevent the resurgence of Populism by disenfranchising prac

tically all of the blacks and a large num ber of whites; is that

not correct?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. T he idea was to prevent blacks from becoming a swing

vote and thereby powerful and useful to some group of whites

such as Republicans?

A. Yes, sir, that’s correct.

Q. T he phrase that is quite often used in the Convention is

to, on the one hand lim it the franchise to intelligent and vir

tuous, and on the other hand to disenfranchise those that

Francis Caffee refers to as “corrupt and ignorant,” or some

times referred to as the ignorant and vicious?

A. T h a t’s right.

Q. Was that not interpreted by the people at that Constitu

tional Convention to mean that they wanted to disenfranchise

practically all of the blacks and disenfranchise those people

who were lower class whites?

A. T h a t’s correct.

# * * #

[74] Q. Have you done any research into the relative convic

tion rates of blacks and whites for all crimes?

A. Yes, sir. As of September 1st, 1902, 87 percent of persons,

males who were in State custody were black, and 13 percent

were white. 94 percent of persons who were in county custody

were black, and 6 percent were white.

Q. And the population of the State of Alabama was approxi

mately 40 percent black at that time; is that correct?

A-26

A. Actually, 45. It was 55 percent white, 45 percent black.

Q. And about 45 percent of the male adult population was

also black; is that not correct?

A. Yes, sir, that is correct.

# # # #

[79] Q. And what we come out with is about a ten or eleven

times as many blacks who were disenfranchised by the crimes

provision as whites were; is that correct?

A. Well, that follows statistically from the evidentiary base.

T h a t is to say, the evidentiary base I am using, 1902, shows

80 something percent of blacks in State custody, prisoners in

State custody, and 94 percent of blacks in county custody were

prisoners in county custody were black, and consequently, since

I am extrapolating from those figures, therefore the extrapola

tion is going to show the same relationships, necessarily. T hat

would be about 90 percent.

Q. So all of the evidence that you have found shows that

about ten times as many blacks were disenfranchised by the

crimes provision as whites? We are talking about in raw num

bers.

[80] A. Yes, sir, I do understand exactly what you are saying.

And that is exactly correct, except that I worry slightly about

the way in which you have phrased it. If you will perm it me,

w ithin the perimeters of the prison population as it stands,

the crimes clause, it appears to me, is operating essentially

across the board of the prison population and it is drawing

blacks and whites to disfranchisement in about the same per

centage as the prison population at large. T he crimes clause

would disfranchise all of the persons in State custody and about

two-thirds of the persons in county custody, and it draws from

across the board. But w ithin that lim itation, if you accept that

lim itation, then the answer to your statement is yes.

Q. Near the end of the Convention, John Knox did make a

speech to the Convention in which he summarized the work of

the Convention, and in that speech is it not correct that he said

that the provisions of the Suffrage Article would have a dispro

A-27

portionate impact on blacks, bu t he disputed that that would

be violation of the Fifteenth Amendment?

A. Yes, sir, that is true. Repeatedly through the debates, the

delegates say that they are interested in disfranchising blacks

and not interested in disfranchising whites. And in fact, they go

out of their way to make that point, and it is so startling and

offensive to m odern [81] sensibilities, that we tend to be — that

tends to overwhelm us. If you read the four volumes of the

official proceedings — a fate I wouldn’t wish on anyone — but

if you happen to, you will come away with the sense that race

simply dominates the proceedings of the Convention. But the

point that I am trying to make is that this is really speaking to

the galleries, that it is attem pting to say to the white electorate

that must ratify this constitution what it is necessary for that

white electorate to be convinced of in order to get them to vote

for it, and not merely echoing what a great many delegates say.

Now, I would point out to you that there are occasions in the

debates, particularly in the debate over the motions to extend

the time of the temporary plan, that the desire to disfranchise

poor whites pops out in the words of the majority of the Suff

rage Committee. But in general, the delegates aggressively say

that they are not interested in disfranchising any whites. I

think falsely, bu t that’s what they say.

Q. So they were simply trying to overplay the extent to which

they wanted to disenfranchise blacks, bu t that they did desire

to disenfranchise practically all of the blacks?

A. Oh, absolutely, certainly.

A-28

J. Morgan Kousser, PhD,

called as a witness, having been first duly sworn, was examined

and testified as follows:

Exam ination

[3] By the reporter:

Q. Please state your full name.

A. By name is J. Morgan Kousser, k-o-u-s-s-e-r. My address is

1818 N orth Craig Avenue, Altadena, California.

Q. Please state your educational background beginning with

college. Please include the subjects of your masters thesis and

doctoral dissertation, if any.

A. I received an A.B. at Princeton University in 1965, a M.

Phil, p-h-i-1, at Yale in 1968, and a P.h.D. from Yale in 1971

where I studied under Professor C. Vann W oodward, v-a-n-n.

T he topic of my dissertation was, “T he shaping of southern

politics, suffrage restriction and the establishment of the one

party south, 1880 to 1910.”

* * * *

[5] Q. According to your research, was there much discussion

at the 1901 Alabama Constitutional Convention regarding the

desirability of the disenfranchising blacks?

A. T he Alabama Constitutional Convention of 1901 was

called for the prim e purpose of disfranchising blacks. All

scholars agree upon the subject. T here was considerable dis

cussion on and frank discussion of the subject by delegates to

the convention as well as by newspapers, executive committees

of the political parties and contemporaries in general in the

period leading up to the Constitutional Convention.

Q. W hat was the tenor of the discussions?

A. T h e general tenor of the discussion was that virtually all

Democrats wanted to eliminate virtually all blacks from the

electorate and that white populace of Republicans as well as

blacks, most of whom were Republican, wished to keep free

and im partial suffrage for blacks.

A-29

Q. W hat was the specific source of the crime provision which

was eventually adopted as Section 182 of the Constitution?

[6] A. Let me turn now to the question of the intentions of

the framers of the Section 182 of the Alabama Constitution of

1901. T here is very little direct evidence on the intention of

all of the delegates who voted for Section 182, or even on the

intentions of the Suffrage Committee of the Constitutional

Convention. T he committee did not keep any m inutes or other

records of internal debate, nor did any of its m ajor figures

leave paper collections relevant to this issue.

Newspapers carried a great deal of information and opinion

on suffrage plans and strategies at the time of the 1901 conven

tion, bu t no newspaper reporter seems to have had access to

the committee debates.

T here was almost no debate on the floor of the convention

on Section 182. T h is m ight be taken to imply that the dele

gates did not think the section im portant. I believe that this

would be a m isinterpretation although 1 would not contend

that the delegates thought the section as im portant as Sections

180 and 181.

T he real reason that Sections 180 to 181 were subject to

more debate is that they were more controversial, that the

fighting grandfather clause was more clearly unconstitutional

and unfair, and the poll tax and literacy and property tests

were likely to disfranchise more whites than was Section 182.

A section such as 182, which was, as [7] everyone apparently

knew, aimed chiefly at blacks and which seemed sufficiently

neutral on its face to pass muster before the racist courts of the

day was certain to be less controversial in this all-white con

vention, which was overwhelmingly committed to the disfran

chisement of blacks.

Since direct evidence of the intentions of the delegates on

this section is not available, we must rely on indirect and some

what fragmentary evidence. Fortunately, all the indirect evi

dence points in the same direction.

T he intentions of the delegates on Section 182 must be

viewed in the context of the whole convention. There is no

A-30

question that the overriding issue in calling the convention

was black disfranchisement. T he proponents and delegates ad

m itted this openly and repeatedly, and all scholars agree on

this fact.

See, for example, Alabama Constitutional Convention Jour

nal 1901, pages 1755, et seq, and pages 1776, et seq, and Kous-

ser, The Shaping of Southern Politics, pages 165 to 171 and

250 to 251.

T he fact that the delegates wanted and expected to disfran

chise some whites as well, despite their guarantees to the con

trary before, during and after the convention, does not under

mine an equal protection challenge, even under the doctrines

common in 1901, for they framed the suffrage restrictions to

have a vastly disproportionate [8] effect on blacks.

Many of the delegates were lawyers, and they were familiar

with the reigning, relevant case then; the Chinese laundryman

case, Yick, y-i-c-k, Wo, w-o, versus Hopkins, 181 U.S. 356, 1886;

and knew that barring a few whites would not be a constitu

tional saving grace.

In any event, their intention that the new suffrage regula

tions, as a whole, would have a disproportionate impact on

blacks is very clear.

Another indirect piece of evidence of their intent is present

on the face of the law in what crimes the conventioners defined

as disfranchising, that they added to the 1875 Constitution’s

list, crimes which they thought blacks would be disproportion

ately likely to be convicted of, is especially apparent in their

inclusion of sex-related crimes, living in adultery, assault and

battery on the wife, rape and miscegenation.

Does anyone have to be rem inded about the contemporary

Southern fixation on black men raping white women, or the

fact that whites were never convicted of miscegenation, and

small property crimes, vagrancy and petty theft? Even if we

had no better evidence than this of the in tent of the framers,

the manifestly disproportionate and racially discriminatory im

pact which the enforcement of this extended list would be ex

pected to have would have been sufficient to indicate to me,

A-31

at least, that the [9] framers were aim ing to disfranchise blacks

by this section.

# # # #

[16] T o sum up this point, the Alabama disfranchises closely

studied methods of disfranchisement elsewhere and in every

state which had a petty crimes provision the intent was the

same; to disfranchise blacks. Further, in their own state, they

must have known that it was chiefly blacks who were convicted

of such crimes, and thus could have understood the impact of

the clause qu ite easily.

But, we have more direct evidence of the in tent of the p rin

cipal author of Section 182, John F. Burns, b-u-r-n-s; in his

original draft Burns included:

[17] “. . . all those who are bastards or loafers or who may

be infected with any loathsome or contagious disease.”

I t was, of course, common at the time for whites to think

that these traits were predom inant among blacks.

Burns also believed, in the summary of a recent scholar:

“T he crime of wife beating alone would disqualify 60

percent of the Negroes.”

T he quotation is from Jimmie, j-i-m-m-i-e, Frank Gross,

g-r-o-s-s, Alabama Politics and the Politics and the Negro, 1874

to 1901, unpublished P.h.D. dissertation, University of Geor

gia, 1969, page 244.

Similarly, see McMillan, Constitutional Development in Ala

bama, page 275, footnote 76.

Burns says:

“Actions again demonstrate the connection between

past impact and present in tention.”

For as a long-time justice of the peace in Black-Belt Burns

ville, Burns knew very well what crimes black people were

likely to be convicted of, and therefore was easily able to tailor

Section 182 to cover crimes which [18] would have the maxi

A-32

mum racially discriminatory impact. His position as chief

fram er of the section lends special importance to his clear and

obvious intent.

* * * #

[24] Let me summarize my argum ent as a whole. Most of the

evidence as to the intentions of the framers of Section 182 is in

direct, but all of it points in the same direction. T he section

was designed to have a racially discriminatory disproportionate

impact on blacks, drafted by ingenious lawyers who were try

ing to circumvent the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

while seeming not to violate their letter. Section 182 may be

defended by similarly clever bu t obviously flawed arguments.

Looking at all the evidence, it is my view as a historian that

the intention of the framers was clear.

Subm itted by

tes S. W ard

Special Assistant Attorney General

Attorney for Nell H unter,

et al-Appellants

COUNSEL

C orley , M ongus, Bynum & D e Buys, P .C .

2100 16th Avenue South

Birmingham, Alabama 35205

(205) 939-0811

A-33

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, James S. W ard, a m em ber of the Bar of the Supreme Court

of the U nited States and counsel of record of Nell H unter,

et al, individually and on behalf of all other members of Board

of Registrars in the State of Alabama, appellants herein, hereby

certify that on November 21, 1984, pursuant to Rule 33,

Rules of the Supreme Court, I served three copies of the fore

going Jo in t Appendix on each of the parties herein as follows:

On Victor Underwood and Carmen Edwards, for themselves

and all others similarly situated, appellees herein, by deposit

ing such copies in the U nited States Post Office, Birmingham,

Alabama, with first class postage prepaid, properly addressed

to the post office address of Edward Still and Neil Bradley, the

above named appellees counsel of record, at Edward Still,

Suite 400, Commerce Center, 2027 First Avenue North, Bir

mingham, Alabama 35203 and Neil Bradley, ACLU Founda

tion, 52 Fairlie Street NW , Atlanta, Georgia 30303.

On the Solicitor General, Departm ent of Justice, by deposit

ing such copies in the U nited States Post Office, Birmingham,

Alabama, with first class postage prepaid, properly addressed

to the post office address of T he Solicitor General, Departm ent

of Justice, W ashington, D.C. 20530.

On W illiam Bradford Reynolds, Assistant Attorney General,

Charles J. Cooper, Deputy Assistant Attorney General, and

Brian K. Landsberg, Esquire, by depositing such copies in the

U nited States Post Office, Birmingham, Alabama with first

class postage prepaid, properly addressed to the post office ad

dress of W illiam Bradford Reynolds, Assistant Attorney Gen

eral, Charles J. Cooper, Deputy Assistant Attorney General

and Brian K. Landsberg, Esquire, United States Departm ent of

Justice, W ashington, D.C. 20530.

All parties required to be served have been served.

A-34

Dated: November 21, 1984

lecial Assistant Attorney General

Attorney for Appellants

A-35

AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE

STA TE OF ALABAMA )

JEFFERSON CO UN TY )

I, James S. W ard, depose and say that I am an attorney in the

law firm of Corley, Moncus, Bynum & DeBuys, and I am the

attorney of record for Nell H unter, et al, individually and on

behalf of all other members of Board of Registrars in the State

of Alabama, the appellants herein, and that on the 21st day of

November, 1984, pursuant to Rule 33, Rules of the Supreme

Court, I served three copies of the foregoing Jo in t Appendix on

each of the parties required to be served therein, as follows:

On Victor Underwood and Carmen Edwards, for themselves

and all others similarly situated, appellees herein,‘ by deposit

ing such copies in the U nited States Post Office, B irm ingham ^

Alabama, with first class postage prepaid, properly - addjessecT

to the post office address of Edward Still and N eil Bradley; the

above named appellees counsel of record, at Edward Still,

Suite 400, Commerce Center, 2027 First Avenue North, Bir

mingham, Alabama 35203 and Neil Bradley, ACLU Founda

tion, 52 Fairlie Street NW, Atlanta, Georgia 30303.

On the Solicitor General, Departm ent of Justice, by deposit

ing such copies in the U nited States Post Office, Birmingham,

Alabama, with first class postage prepaid, properly addressed

to the post office address of T he Solicitor General, Departm ent

of Justice, W ashington, D.C. 20530.

On W illiam Bradford Reynolds, Assistant Attorney General,

Charles J. Cooper, Deputy Assistant Attorney General, and

Brian K. Landsberg, Esquire, by depositing such copies in the

U nited States Post Office, Birmingham, Alabama with first

class postage prepaid, properly addressed to the post office ad

dress of W illiam Bradford Reynolds, Assistant Attorney Gen

eral, Charles J. Cooper, Deputy Assistant Attorney General and

Brian K. Landsberg, Esquire, U nited States Departm ent of

Justice, W ashington, D.C. 20530.

A-36

Sworn to and subscribed before

me this the 21st day of November, 1984.