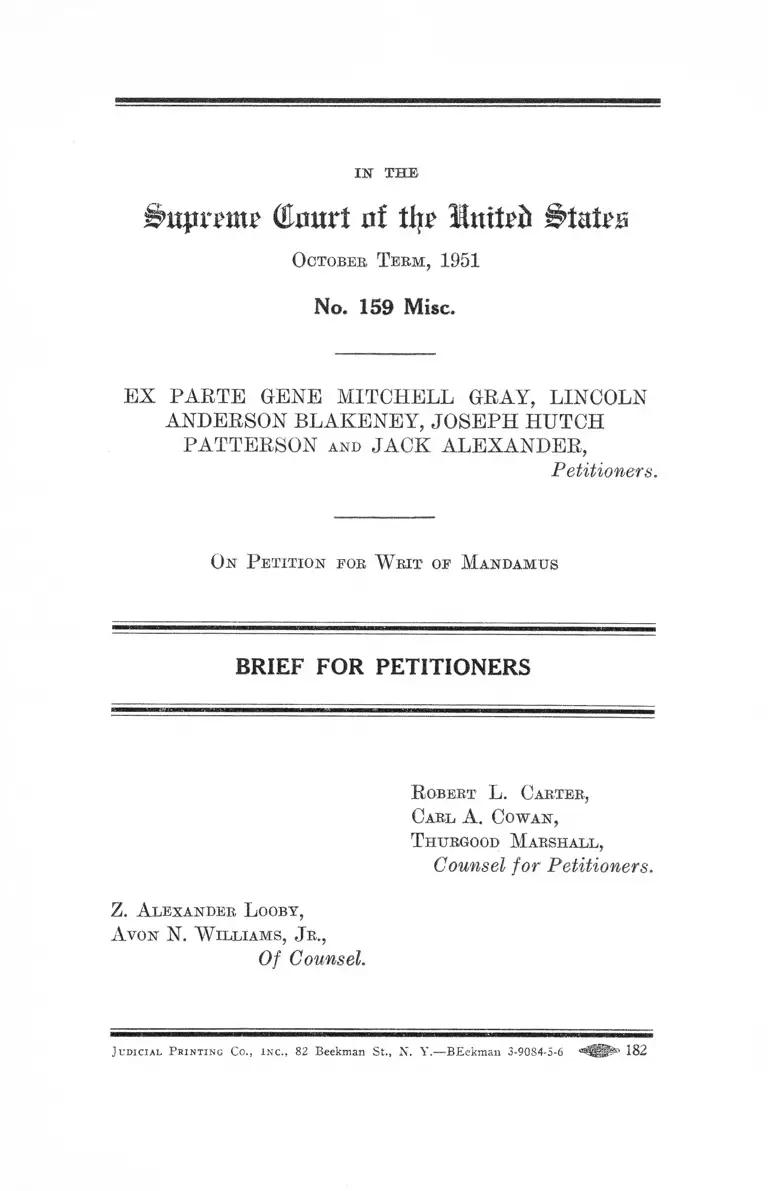

Ex Parte Gene Mitchell Gray Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ex Parte Gene Mitchell Gray Brief for Petitioners, 1951. 3df5fe14-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/985b83a4-f018-409b-8f81-ff22f76ce0fa/ex-parte-gene-mitchell-gray-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

ujinw ( ta r t ni tip Mniteft States

October T erm, 1951

No. 159 Misc.

IN THE

EX PAETE GENE MITCHELL GEAY, LINCOLN

ANDERSON BLAKENEY, JOSEPH HUTCH

PATTERSON a n d JACK ALEXANDEE,

Petitioners.

On P etition fob W rit of Mandamus

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

B obert L. Carter,

Carl A. Cowan,

T hurgood Marshall,

Counsel for Petitioners.

Z. Alexander L ooby,

Avon N. W illiams, J r.,

Of Counsel.

J u d ic ia l P r in t in g Co., in c ., 82 Beekman St., N. Y.— BEekman 3-9084-5-6 182

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 2

Statement of the Case................................................... 3

Error Relied On.............................................................. 6

Summary of Argument.................................................. 6

Argument ........................................................................ 8

I— This cause is one in which a three-judge court

has jurisdiction ...................................... 8

II— If Review is not available on direct appeal

mandamus will lie to require the Court below to

assume jurisdiction ................................................ 10

Conclusion....................................................................... 12

Cases Cited

Bd. of Supervisors, La. State University v. Wilson,

340 U. S. 9 0 9 ..:......................................................... 8

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 IJ. S. 45.................... 8

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U. S. 315....... ................. 10

Chicago v. Fieldcrest Dairies, Inc., 316 U. S. 168........ 10

Ex parte Bradstreet, 32 U. S. 64, 8 L. ed. 577............. 12

Ex parte Bransford, 310 U. S. 354, 355...................... 10

Ex parte Collins, 277 U. S. 565....... ............................ 10

Ex parte Fahey, 332 U. S. 258, 260................................. 12

Ex parte Hobbs, 280 U. S. 168....................................... 9

Ex parte Metropolitan Water Co., 220 U. S. 5 3 9 ..... 10

Ex parte Northern Pacific Ry. Co., 280 U. S. 142........ 10

Ex parte Poresky, 290 U. S. 30.................................... 10

Ex parte Public Nat’l Bank, 278 U. S. 101................ 11

Ex parte Simmons, 247 U. S. 231, 239.......................... 12

Ex parte Skinner & Eddy Corp., 265 U. S. 86............. 12

11 I N D E X

PAGE

Ex parte United States, 287 U. S. 241.......................... 12

Ex parte United States, 319 U. S. 730.......................... 12

Ex parte Williams, 277 U. S. 267................................... 10

Gong Lnm v. Bice, 275 U. S. 78..................................... 8

Gully v. Interstate Natural Gas Co., 292 U. S. 16......... 10

In re Buder, 271 U. S. 461...................................... . 10

International Garment Workers Union v. Donnelly

Garment Co., 304 U. S. 243........................................ 9

Jameson & Co. v. Morgenthau, 307 U. S. 171.............. 10

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1................................... 12

McCabe v. A. T. & S. P. By. Co., 235 U. S. 151......... 8

McCullough Tool Co. v. Cosgrove, 309 U. S. 634....... 12

McLaurin v. Board of Begents, 339 U. S. 637...............8,10

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337......... 8, 9

Moore v. Fidelity & Deposit Co., 272 U. S. 317............. 9

Oklahoma Gas & Electric Co. v. Oklahoma Packing

Co., 292 U. S. 386.......................................................9,10

Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Bussell, 261 U. S. 290.. . 10

Osage Tribe of Indians v. Ickes, 45 E. Supp. 179, 186,

187 (D. D. C. 1942)............................................. 11

Phillips v. United States, 312 U. S. 246................ 9

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537................................. 8

Public Service Commission of Missouri v. Brashear

Freight Lines, Inc., 312 U. S. 621............................. 10

Boche v. Evaporated Milk Ass’n, 319 U. S. 21, 32... 12

Sipuel v. Board of Begents, 332 U. S. 631.................... 8

Smith v. Wilson, 273 U. S. 388......... ............................ 9

Spector Motor Service v. McLaughlin, 323 U. S. 101. . 10

Stratton v. St. Louis S. W. By. Co., 282 U. S. 10......... 9,10

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629..................................... 8

Virginia v. Paul, 148 U. S. 107.

Virginia v. Bives, 100 U. S. 313

12

11

I N D E X 111

Statutes Cited

p a g e

Tennessee Code, Sections 11395, 11396, 11397. . .2, 4, 5, 6, 8

Tennessee Constitution, Article 11, Section 12.. .2, 4, 5, 6, 8

United States Code, Title 28, Sections 1651(a) and 1253 2

United States Code, Title 28, Sections 2281 and 2284. .1, 5, 8

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment. .2,5, 8

Treatise

Bowen, When are Three Federal Judges Enquired

(1931), 16 Minn. L. Rev. 1, 39-42................ ............ Un

IN THE

B n p x m x x (Hour! of % Mxxxtxb States

O ctober T e r m , 1951

No. 159 Misc.

-------------- — » — ■ --------------

Ex P arte Gene Mitchell Gray, L incoln A nderson

Blakeney, J oseph H utch P atterson

and J ack Alexander,

Petitioners.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

After notice and hearing, the statutory three-judge

District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee con

vened pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Section

2281 disclaimed jurisdiction and remanded the cause for

proceedings before the District Judge in the District peti

tioners had filed their complaint. An opinion setting forth

the reasons for their action was filed on April 13, 1951.

It appears at pages 35-40 of the record and is not officially

reported.1 District Judge T aylor, without further hear

ing or notice to the parties, on April 20, 1951, filed an

opinion in which he found that; petitioners had been denied

the equal protection of the laws, but refused to grant in

junctive relief. The cause was retained “ for such orders

1 All record citations are to the record filed in the appeal phase of these

proceedings, now pending before this Court as Case #120.

2

as may be proper when it appears that the appropriate law

has been finally declared.” His opinion is reported in 97

F. Snpp. 463 and may be found at pages 40-47 of the

record.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1651(a) since the ordinary

remedy of appeal and certiorari may be unavailable and in

adequate, and petitioners’ right to take an appeal in this

case, pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Section

1253 is beclouded with doubt.

Petitioners made application in the court below for a

preliminary and permanent injunction to restrain the en

forcement of certain constitutional and statutory pro

visions of the State of Tennessee, and a December 4,

1950 order of the Board of Trustees of the University

of Tennessee, on the grounds that these aforesaid pro

visions and order deny to petitioners the equal protection

of the laws as secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States (R. 1-20). In its

answer, the state defended its refusal to admit petitioners

to the University of Tennessee on the grounds that it had

no other recourse under Article 11, Section 12 of the Con

stitution and under Sections 11395, 11396 and 11397 of the

Code of Tennessee (R. 25-27). Thus, the issue of the con

stitutionality of the order of an administrative agency and

of the laws of the State of Tennessee were squarely in

issue in these proceedings, and since injunctive relief is

sought, determination by a three judge court is made man

datory under federal statutes.

3

Statement of the Case

Petitioners, having met all lawful requirements, made

due and timely application for admission to the graduate

school and the law school of the University of Tennessee.

Gene Mitchell Gray sought permission to enroll in the

graduate school commencing in the fall quarter of 1950,

and Jack Alexander desired approval of his application

for enrollment in the graduate school beginning in the win

ter quarter of 1951. Both Lincoln Anderson Blakeney and

Joseph Hutch Patterson desired to enroll in the first-year

class of the law school in the winter quarter of 1951 (E. 9).

The University of Tennessee is the only state institution

offering the courses petitioners desire to pursue, and they

would have been admitted except for the fact that they are

Negroes (E. 6). On December 4, 1950, the Board of

Trustees of the University of Tennessee met and denied

petitioners’ application solely because of their color (E.

14). Its action was embodied in the following formal

order:

“ Whereas, the Constitution and the Statutes of

the State of Tennessee expressly provide that there

shall be segregation in the education of the races in

schools and colleges in the State and that a viola

tion of the laws of the State in this regard subjects

the violator to prosecution, conviction, and punish

ment as therein provided; and,

“ Whereas, this Board is bound by the Consti

tutional provision and acts referred to;

“ Be it therefore resolved, that the applications

by members of the Negro race for admission as

students into The University of Tennessee be and

the same are hereby denied” (E. 14).

The applicable constitutional and statutory provisions

on which this order was based are:

4

Article 11, Section 12 of Constitution of Tennessee:

” . . . And the fund called the common school

fund, and all the lands and proceeds thereof . . .

heretofore by law appropriated by the General As

sembly of this State for the use of common schools,

and all such as shall hereafter be appropriated, shall

remain a perpetual fund, . . . and the interest thereof

shall be inviolably appropriated to the support and

encouragement of common schools throughout the

State, and for the equal benefit of all the people

thereof. . . . No school established or aided under

this section shall allow white and negro children

to be received as scholars together in the same

school. . . . ”

Section 11395 of the Code of Tennessee:

“ . • . It shall be unlawful for any school, acad

emy, college, or other place of learning to allow

white and colored persons to attend the same school,

academy, college, or other place of learning.”

Section 11396 of the Code:

“ . . . It shall be unlawful for any teacher, pro

fessor, or educator in any college, academy, or school

of learning, to allow the white and colored races to

attend the same school, or for any teacher or edu

cator or other person to instruct or teach both the

white and colored races in the same class, school, or

colleg-e building, or in any other place or places of

learning, or allow or permit the same to be done with

their knowledge, consent or procurement.”

and

Section 11397 of the Code:

” . . . Any person violating any of the provisions

of this article, shall be guilty of misdemeanor, and,

upon conviction, shall be fined for each offense fifty

dollars, and imprisonment not less than thirty days

nor more than six months.”

5

Petitioners thereupon filed a complaint on January 12,

1951, in the court below, in the nature of a class suit in

which application was made for both a preliminary and

permanent injunction seeking to restrain the enforcement

of the December 4 order of the Board of Trustees, and

Article 11, Section 12 of the Constitution and Sections

11395, 11396 and 11397 of the Code of Tennessee on the

grounds that the aforesaid provisions and order under

attack deprived petitioners of rights secured under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States (R. 1-20).

On February 1, 1951, the state filed its answer, in which

no material allegations in petitioners’ complaint was con

troverted and in which the denial of petitioners’ admission

to the University of Tennessee wTas defended on the grounds

that such denial was required by its constitution and stat

utes (R. 25-27).

On February 12,1951, petitioners filed a motion for judg

ment on the pleadings (R. 28). The court below, which had

been convened pursuant to Title 28, United States Code,

Sections 2281 and 2284 (R. 28-29) held a hearing in Knox

ville, Tennessee, on March 13, 1951, and on April 13, 1951,

handed down an opinion in which jurisdiction was dis

claimed; the three-judge court was ordered dissolved; and

the cause remanded to District Judge Robert Taylor, in

whose District the complaint had been fded, for further

proceedings (R. 35-40).

On April 20, 1951, Judge Taylor held that the state’s

refusal to admit petitioners to the University of Tennessee

constituted a denial of the equal protection of the laws but

refused to issue any affirmative order in enforcement of

petitioners’ rights (R. 40-47). The cause was brought here

on direct appeal. Since the right to direct appeal is in

doubt and may be inappropriate, petitioners filed a motion

for leave to file a petition for writ of mandamus to secure

6

the issuance of a mandatory writ from this Court directing

the three judge court to reconvene and to make a final de

termination in this cause. The motion was granted on Octo

ber 15, 1951, and a rule to show cause issued. Response to

the rule was made and on December 3, 1951, this Court

ordered argument on this phase of the case.

E rro r R elied O n

T h e c o u r t b e lo w e r re d in re fu s in g to e x e rc ise its ju r is

d ic tio n w h ich h a d b een p ro p e r ly in v o k ed p u rs u a n t to th e

re q u ire m e n ts o f T itle 28, U n ited S ta te s C ode, S ections 2281

a n d 2284.

Sum m ary of A rgum ent

Petitioners are here seeking the issuance of a writ of

mandamus to require the specially constituted United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee, con

sisting of the Hon. Shackelford Miller, Jr., Judge, United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, L eslie R.

Dabr, and R obert L. Taylor, Judges, United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee to reconvene

in order to finally determine petitioners’ right to a tempo

rary and a permanent injunction as applied for in their

complaint.

Petitioners sought injunctive relief in the court below

against enforcement of a statewide policy, as evidenced in

the December 4th order of the Board of Trustees of the

University of Tennessee, Article 11, Section 12 of Constitu

tion and Sections 11395, 11396 and 11397 of the Code of Ten

nessee, all of which prohibit the admission of Negroes to

the graduate and professional schools of the University

of Tennessee. Because of the nature of the case a hearing

and determination by a three judge court was mandatory.

7

If a single judge had refused to convene a three judge

court, it is settled that petitioners’ proper recourse was

to apply for writ of mandamus in this Court.

Here, however, a three judge court was properly

convened, and after notice and hearing held on March 13,

1951, the court declared itself to he without jurisdiction and

issued an order dissolving the statutory court and remanded

the cause for further proceedings before District Judge

Eobert Taylor. Such proceedings subsequently took place

in accordance wTith this order. The order remanding the

cause to Judge Taylor, sitting alone, could not confer juris

diction which he did not possess. Only a three-judge dis

trict court has jurisdiction to hear and determine peti

tioners’ cause.

This petition has been filed as an alternative remedy in

the event the appeal now pending is held to be procedurally

improper. "Where review by appeal is unavailable, man

damus will lie to require a lower federal court to exercise

jurisdiction in a proper case. In this case, if the order dis

solving the three-judge court cannot be reviewed on ap

peal, a writ of mandamus should issue directing the three

judges who signed the order to reconvene and render a

final decision in this case.

8

ARGUMENT

I

This cause is one in which a three-judge court has

jurisdiction.

A preliminary and a permanent injunction to restrain

the enforcement of the December 4th, order of the Board

of Trustees, refusing to admit petitioners to the University

of Tennessee pursuant to Article II, section 12 of the Con

stitution of the State and Sections 11395, 11396 and 11397

of the Code of Tennessee are here being sought on the

grounds that the order, constitutional provision and stat

utes deprive petitioners of their right to equal educational

opportunities as secured under the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States. The University officials are state officers,

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337; and the

Board of Trustees of the University of Tennessee is an

administrative board within the meaning of Title 28,

United States Code, Sections 2281 and 2284. McLaurin

v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637; Board of Supervisors,

La. State University v. Wilson, 340 U. S. 909. Petitioners’

claim that the state has deprived them of the equal pro

tection of the laws presents a substantial federal question.

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629; Sipuel v. Board of

Regents, 332 U. S. 631.

The court below stated that state legislation requiring

segregation was not unconstitutional because of the feature

of segregation. In support of this proposition, Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537; McCabe v. A. T. & S. F. Ry. Co.,

235 U. S. 151; Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 45; and

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 were cited. It is alleged that

Sweatt v. Painter, supra, did not change this rule. It sought

to redefine the issues raised by describing them as allega

tion of unjust discrimination under the equal protection

9

clause rather than of the constitutionality of state segrega

tion statutes (R. 39-40). What we take the court to mean is

that in the light of these decisions, petitioners’ claim that

the denial of their admission to the University of Tennessee,

pursuant to the state’s policy requiring the segregation of

the races in all phases of its educational system including

professional and graduate education, is unconstitutional has

been foreclosed, and that hence that claim does not present

a substantial federal question. Even assuming arguendo

the correctness of the court’s view, we fail to see how it

affects petitioners’ right to have their applications for in

junctive relief heard and determined by a three judge court.

At the very least those cases stand for the proposition that

enforced racial segregation is permissible under the Con

stitution as long as the facilities provided Negroes are

equal to those available to white persons. This is the con

dition which must be satisfied if segregation laws are to be

held constitutional under the separate but equal doctrine.

Ergo, where that condition has not been met such statutes

are necessarily invalid. Certainly where the record shows

that: (1) the University of Tennessee is the only state in

stitution offering the courses petitioners desire to pursue;

(2) that they have been denied admission thereto solely

because of their race, pursuant to state policy; and (3) that

petitioners seek to enjoin enforcement of that policy on the

grounds that it conflicts with the federal constitution, a sub

stantial claim of unconstitutionality has been made. See

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra.

We contend that all the ingredients essential to the

jurisdiction of a three judge federal court have been met.

See Stratton v. St. Louis S. W. Ry. Co., 282 U. S. 10; Smith

v. Wilson, 273 U. S. 388; Moore v. Fidelity & Deposit Co.,

272 U. S. 317; International Garment Workers Union v.

Donnelly Garment Co., 304 IT. S. 243; Ex parte Hobbs, 280

U. S. 168; Phillips v. United States, 312 U. S. 246; Okla

homa Gas & Electric Co. v. Oklahoma Packing Co., 292

10

U. S. 386; Ex parte Poresky, 290 U. S. 30; In re Buder,

271 U. S. 461; Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Russell, 261

U. S. 290. While equity jurisdiction may be withheld in

the public interest in exercise of sound discretion, see Spec-

tor Motor Service v. McLaughlin, 323 IT. S. 101; Chicago r.

Fielderest Dairies, Inc., 316 IT. S. 168; Burford v. Sun Oil

Co., 319 IT. S. 315, the public interest in this case demands

that the chancellor exercise his power. See McLaurin v.

Board of Regents, supra. Jurisdiction of a three judge

district court was properly invoked, and the court below

was in error in refusing to decide this case.

II

If review is not available on direct appeal man

damus will lie to require the court below to assume

jurisdiction.

It is clear that where a single judge refuses to convene

a three judge court, this Court may issue writ of man

damus directing him to do so. Stratton v. St. Louis S. W.

Ry. Co., supra at page 16; Ex parte Collins, 277 IT. S. 565,

566; Ex parte Bramsford, 310 U. S. 354, 355; Ex parte

Metropolitan Water Co., 220 IT. S. 539; Ex parte Williams,

277 IT. S. 267; Ex parte Northern Pacific Ry. Co., 280 IT. S.

142. Under such circumstance mandamus is the only ap

propriate procedural remedy, since direct appeal to this

Court lies only from a decision by a properly convened

three judge court. Oklahoma Gas d Electric Co. v. Okla

homa Packing Co., supra; Jameson & Co. v. Morgenthau,

307 U. S. 171; Public Service Commission of Missouri v.

Brashear Freight Lines, Inc., 312 U. S. 621; Gully v. Inter

state Natural Gas Co., 292 U. S. 16. Of course, the pro

ceedings of District Judge T aylor subsequent to the

order dissolving the three judge court are without effect,

and he could be required to again convene a three judge

11

court. That would be an indirect method of indicating to

the court belowr that it must assume jurisdiction of this

cause. The vice, which petitioners seek to correct, how

ever, concerns the refusal of the three judge court which

had been properly convened to exercise jurisdiction which,

we submit, it clearly possessed. We take the position that

the order dissolving the court is appealable in that it was

an effective denial of petitioners’ application for injunc

tive relief. A judgment of dismissal or an express denial

of injunctive relief, however, may be considered essential

for this Court to have jurisdiction on appeal. In that

event, we submit, mandamus will lie.

The only decision by this Court, which counsel for

petitioners have found, on all fours with this case is Ex

parte Public Nat’l Bank, 278 U. S. 101. In that case peti

tioners sought to invoke the jurisdiction of a three-judge

court. That court disclaimed jurisdiction, dissolved the

court and ordered the cause to proceed before a single

district judge on the ground that the requirements essen

tial to a three-judge court had not been met. Motion for

leave to file a petition for writ of mandamus to compel

the reassembling of the court of three judges was granted

by this Court, and a rule to show cause issued. After

hearing and argument the rule was discharged, this Court

finding that petitioners’ cause did not require determina

tion by a three-judge court. Accord, Osage Tribe of In

dians v. I ekes, 45 F. Supp. 179, 186, 187 (D. D. C. 1942).

In that case, however, no attempt was made to invoke the

jurisdiction of this Court on appeal and that phase of

the problem was not considered.2

Mandamus will lie where this Court finds that appeal

may be unavailable or inadequate. Virginia v. Rives, 100

2 For a discussion of the procedural problems incident to this ease, See

Bowen, When are Three Federal Judges Required (1931), 16 Minn. L. Rev. 1,

39-42. The author favors mandamus rather than direct appeal as proper

procedural remedy in a situation of this nature.

12

U. 8. 313; Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1; Virginia v.

Paul, 148 TJ. S. 107; Ex parte Skinner & Eddy Corp., 265

U . S. 86; Ex parte Simmons, 247 U. S. 231, 239; Ex parte

Fahey, 332 U. S. 258, 260. It is used in appropriate cases

in aid of this Court’s supervisory power over lower fed

eral courts. McCullough Tool Co. v. Cosgrove, 309 TJ. S.

634; Ex parte United States, 287 U . S. 241. Improper as

sumption or refusal or jurisdiction on a lower federal

court may be reached by this writ. Ex parte United States,

supra, 287 U. S. 241; Ex parte Skinner & Eddy Corp., supra;

Ex parte Bradstreet, 32 U . S. 64, 8 L. ed. 577; Roche v.

Evaporated Milk A ss’n, 319 U. S. 21, 32; Ex parte United

States, 319 U. S. 730. Thus, in this case, if this Court

finds it does not have jurisdiction on appeal, a writ of

mandamus may appropriately be issued to compel the

three-judge court below to reassemble and determine

whether petitioner is entitled to the injunctive relief

prayed for in her complaint.

Conclusion

For these reasons, it is respectfully submitted that a

writ of mandamus should issue to compel the court below

to reassemble as a specially constituted three-judge federal

court and finally decide whether petitioners are entitled

to injunctive relief in the event this Court holds that

petitioners cannot have the order of the court below re

viewed on direct appeal.

R obert L. Carter,

Carl, A. Cowan,

T hurgood Marshall,

Counsel for Petitioners.

Z. A lexander L ooby,

Avon N. W illiams, J r.,

Of Counsel.

(4582)