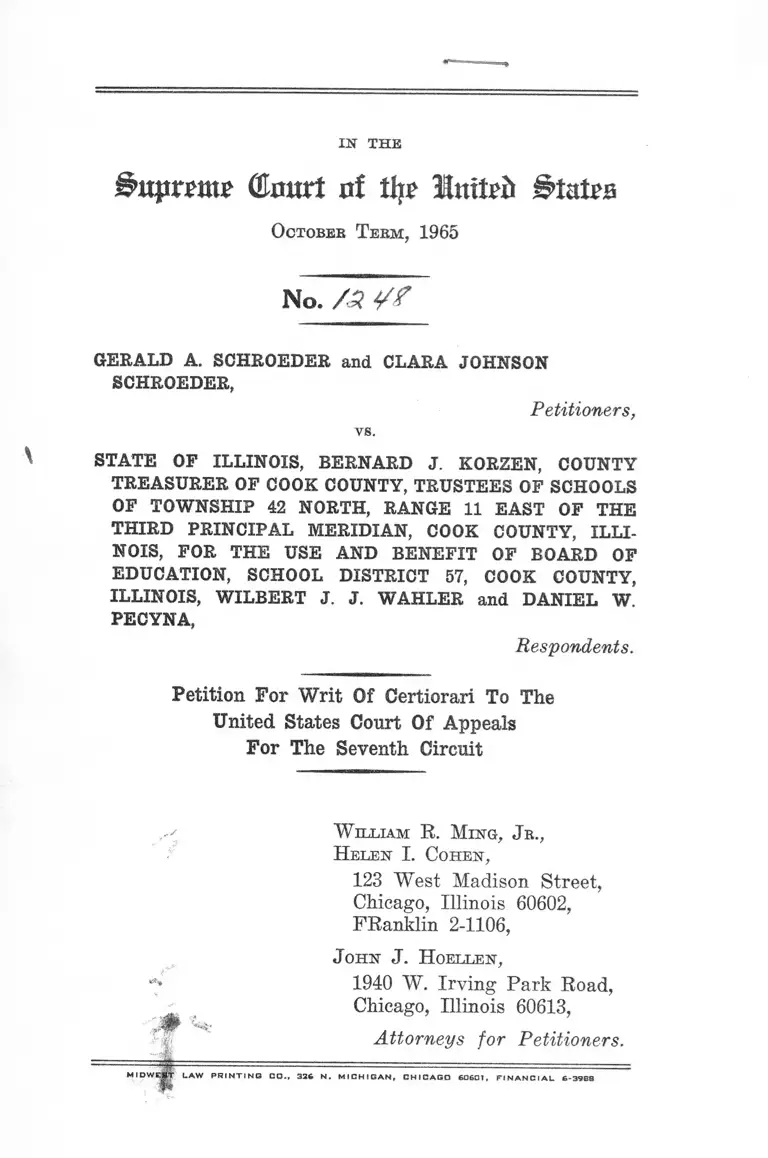

Schroeder v IL Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1965

41 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Schroeder v IL Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1965. 561c8cc8-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/987fac33-97d7-4a1a-a40f-c705ce6db290/schroeder-v-il-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

^uprrmr Court nf thr Hlnttri l t̂atra

Octobeb Tebm, 1965

No. / ? ¥ ?

V

GERALD A. SCHROEDER and CLARA JOHNSON

SCHROEDER,

Petitioners,

vs.

STATE OF ILLINOIS, BERNARD J. KORZEN, COUNTY

TREASURER OF COOK COUNTY, TRUSTEES OF SCHOOLS

OF TOWNSHIP 42 NORTH, RANGE 11 EAST OF THE

THIRD PRINCIPAL MERIDIAN, COOK COUNTY, ILLI

NOIS, FOR THE USE AND BENEFIT OF BOARD OF

EDUCATION, SCHOOL DISTRICT 57, COOK COUNTY,

ILLINOIS, WILBERT J. J. WAHLER and DANIEL W

PECYNA,

Respondents.

Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The

United States Court Of Appeals

For The Seventh Circuit

W illiam R. Ming, J r.,

H elen I. Cohen,

123 West Madison Street,

Chicago, Illinois 60602,

FRanklin 2-1106,

J ohn J . H oellen,

1940 W. Irving Park Road,

Chicago, Illinois 60613,

Attorneys for Petitioners.

= = ^i ——=-------= =========^^

M I D W W L A W P R I N T I N G C O . , 3 2 6 N . M I C H I G A N , C H I C A G O 6 0 6 0 1 , F I N A N C I A L 6 - 3 9 B S

INDEX

PAGE

Opinion Below ..............................................................

Grounds on Which the Jurisdiction of this Court

Is Invoked .................................................................

Question Presented for Review...................................

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ....

Statement of Facts ......................................................

Reasons Relied On for Allowance of a Writ of Cer

tiorari ........................................................................

Argument ........ ............................................................

Conclusion ............... .......... .............. ............................

2

2

3

3

4

11

12

19

Appendices:

A—Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Seventh Circuit.............. la-6a

B—Constitutional Provisions Involved ................. 7a

C—Statutes Involved .......................................... 8a-lla

D—Traverse ...................................................... 12a-18a

11

L ist Or Authorities Cited.

Cases:

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953) .............. 16

City of Cincinnati v. Vester, 281 U.S. 439 (1930) .... 14

County of Allegheny v. Frank Mashuda Company,

360 U.S. 185 (1959) ..................... ......... ......... ..... 15

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940) ................. . 16

Kelly, et al. v. Bowman, et al., 104 F. Supp. 973

(E.D. 111. 1952); aff’d 202 F. 2d 275 (C.A. 7th

1953) ......................................................... ............. 12

McGuire v. Sadler, 337 F. 2d 902 (C.A. 5th 1964) .... 17

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ..................... 18

People ex rel White v. Busenhart, 29 111. 2d 156

(1963) ................. ......... .. ................................... 8, 13

Shelly v. Kramer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ............... ..... 16

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293 (1963) ................ 19

Trustees of Schools, etc. v. Schroeder, 23 111. 2d

74 (1961) and 25 111. 2d 289 (1962) ...... 5, 6, 7, 10, 13

United States v. Price,.....U.S........ , 86 S. Ct. 1152

(1966)...................... .......... ........ ........ .......... ........ 18

Statutes :

28 U.S.C. Sec. 1331(a) .............................. 16, 18, 8a

28 U.S.C. Sec. 1343(3) ................................... 16, 18, 8a

42 U.S.C. Secs. 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985 ................. 8a-lla

Constitution of the United States:

Fifth Amendment ........................ ............................ 7a

Fourteenth Amendment ........................................... 17

IN T H E

Supreme (tart at % Inttrd Stairs

Octobeb Teem, 1965

No.

GERALD A. SCHROEDER and CLARA JOHNSON

SCHROEDER,

Petitioners,

vs.

STATE OF ILLINOIS, BERNARD J. KORZEN, COUNTY

TREASURER OF COOK COUNTY, TRUSTEES OF SCHOOLS

OF TOWNSHIP 42 NORTH, RANGE 11 EAST OF THE

THIRD PRINCIPAL MERIDIAN, COOK COUNTY, ILLI

NOIS, FOR THE USE AND BENEFIT OF BOARD OF

EDUCATION, SCHOOL DISTRICT 57, COOK COUNTY,

ILLINOIS, WILBERT J. J. WAHLER and DANIEL W.

PECYNA,

Respondents.

Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The

United States Court Of Appeals

For The Seventh Circuit

To: The Honorable Chief Justice and Associate Justices

of the Supreme Court of the United States

Your petitioners, Gerald A. Schroeder and Clara John

son Schroeder, respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari

be issued from this Court to review the judgment of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

entered in the above-entitled cause.

—2—

OPINION BELOW.

No formal opinion was rendered by the District Court

for the Northern District of Illinois.

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Seventh Circuit is reported at 354 F. 2d 561 (1965),

and is attached hereto as Appendix A, pp. la-6a.

GROUNDS ON WHICH THE JURISDICTION

OF THIS COURT IS INVOKED.

1. The date of the judgment sought to be reviewed is

November 2, 1965.

2. A timely petition for rehearing was filed. The court

denied the petition for rehearing on February 7, 1966.

3. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

—3—

QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW.

Did a complaint for declaratory judgment and an in

junction which invoked the jurisdiction of the district

court under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343(3), state a cause

of action when the complaint alleged that in violation

of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982 and 1983, defendant public

school district purports to have taken fee simple title to

an entire tract of land owned by petitioners by means of

a state court judgment in an eminent domain proceeding

where the state court had no jurisdiction in such a pro

ceeding to do more than award an easement for use for

school purposes on so much of the land as was needed

for those purposes; that petitioners were denied due

process in the state court proceeding; and the complaint

further alleged that all of the defendants have conspired

in violation of 42 U.S.C. $ 1985 to deprive petitioners of

title to their land by means of a void state court judg

ment and have conspired to deny petitioners equal pro

tection of the laws.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED.

Involved here are the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States (Appendix B,

p. 7a); 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331(a) and 1343(3); and 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981, 1982, 1983 and 1985 (Appendix C, pp. 8a-lla).

STATEMENT OF FACTS.

On or about January 17, 1964, Gerald A. Schroeder and

his wife, Clara Johnson Schroeder, filed a complaint in

the United States District Court for the Northern Dis

trict of Illinois against the State of Illinois; Bernard

J. Korzen, County Treasurer of Cook County, Illinois;

the Trustees of Schools of Township 42 North, Bange 11,

East of the Third Principal Meridian, Cook County,

Illinois, for the use and benefit of the Board of Education

of School District 57 of Cook County, Illinois; Wilbert

J. J. Wahler and Daniel W. Pecyna. The last twm named

defendants are members of the bar of the State of Illinois,

who represented the petitioners in certain proceedings in

the courts of Illinois.

In that complaint petitioners invoked the jurisdiction

of the district court under 28 U.S.C., §§ 1331(a) and

1343(3), and charged the defendant state officers with vio

lating the provisions of 42 U.S.C., §§ 1981, 1982 and 1983

by taking land belonging to petitioners through a void state

court judgment in an eminent domain proceeding. The

complaint further charged all of the defendants with con

spiring to deprive petitioners of title to their land by

means of that void state court judgment and further

conspiring to deny petitioners equal protection of the

laws all in violation of 42 U.S.C., § 1985. Each of the

defendants moved to dismiss the complaint. The district

court dismissed the complaint without a formal opinion

but stated its grounds (Appendix, pp. 149-155), and the

Court of Appeals affirmed.

—5—

In substance, the allegations of the petitioners, which

stand admitted by the several motions to dismiss, are

that petitioners owned, lived on and farmed, and had

done so for some years, approximately 18 acres of land

with frontage of about 1800 feet on a widely traveled

highway in Mt. Prospect, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.

That land AÂas described by the Supreme Court of Illi

nois in Trustees of Schools, etc. v. Schroeder, 23 111. 2d

74, 76, 177 N.E. 2d 178, 179 (1961) as follows:

“The property, Avhich is presently used as a truck

farm, is in many ways unique, making comparison

sales a difficult and inconclusive criterion. It is lo

cated in the heart of a thriving area of shopping-

center development. A short distance to the south

east on Rand Road a 40-acre shopping center for

chain store tenants is under construction and one-

half mile to the northAvest on Rand Road a 60-acre

shopping center is under construction. The subject

property itself is adjacent to the village of Mount

Prospect, being six blocks from the business district

of the village. It is within easy access of schools,

parks, churches, toll roads, expressways and public

transportation. Water and sewers are available at

the property and the surrounding area is building

up rapidly. Rand Road, upon which the tract has

extensive frontage, is United States Route 12 and is

a heavily traveled thoroughfare.”

In 1959 the respondent school district filed a petition in

the Circuit Court of Cook County seeking fee simple title

to the whole 18 acre tract allegedly for school purposes.

The petitioners, then represented by respondents Wahler

and Pecyna, filed an elaborate traverse, later expanded

by amendment with leave of court, inter alia, denying

that the school district sought to take the property for

public purposes and denying that the school district had

—6—

the power to take fee simple title to the land for public

purposes.

After hearing evidence on the issues made by it the

Circuit Court of Cook County denied the traverse. The

question of the value of the property was then presented

to a jury which returned a verdict that the value of the

property was $267,083.33. On a post-trial motion by the

school district the court ruled that unless there was a

remittitur by petitioners to reduce the award to $225,000,

a new trial would be granted. When petitioners refused

to agree to the remittitur the court ordered a new trial.

On appeal from that order the Supreme Court of Illi

nois reversed it in Trustees of Schools, etc. v. Schroeder,

23 111. 2d 74, 177 N.E. 2d 178 (1961), holding that the

trial court had no power to require a remittitur in an

eminent domain proceeding. The Supreme Court, how

ever, though the petitioners raised the issues on the

appeal, refused to pass on the merits of the traverse be

cause the appeal was from an order granting a new trial.

On remand of the proceedings to the Circuit Court of

Cook County, that court entered a judgment awarding

fee simple title in the whole tract to the respondent school

district on condition that it pay petitioners the amount

of the jury’s verdict plus interest. A few days later the

trial court found that the requisite amount had been

deposited with the respondent county treasurer to be paid

to petitioners and entered an order vesting the fee simple

title to the whole tract in the school district.

Petitioners appealed from that order but, without their

knowledge, their counsel, respondents Wahler and Pecyna,

on that appeal, despite the other issues raised in the

■7-

traverse, contended only that a school district of this class

conld not take land by eminent domain within 40 rods of

the owners’ dwelling. That issue was decided against peti

tioners in Trustees of Schools of Township 42, etc. v.

Schroeder, 25 111. 2d 289, 184 N.E. 2d 872 (1962).

When petitioners learned that the various issues raised

by the traverse as to the authority of the school district

to take all of the tract and to take title in fee simple to

the tract had not been raised on the appeal they retained

other counsel, Alfred M. Loeser and Stephen Lee of the

Illinois bar, who immediately filed a petition for rehearing

with the Illinois Supreme Court reasserting the issues

raised on the traverse and asserting that the taking of

petitioners’ property by virtue of the judgment of the

Circuit Court of Cook County in eminent domain under

these circumstances deprived petitioners of their land in

violation of rights protected by the Constitution of the

United States. That petition for rehearing was denied

on September 27, 1962, without opinion.

Mr. Loeser and Mr. Lee continued to represent peti

tioners in these matters until each died while the instant

case was pending in the Court of Appeals for the Seventh

Circuit.

Immediately upon the denial of their petition for re

hearing petitioners sought in the Circuit Court of Cook

County to vacate the condemnation judgment and to stay

the proceedings in condemnation. In that petition it was

reasserted that the school district Avas not taking the land

for public purposes and that the court did not have power

to award more than an easement for school purposes to

so much of the land as might be necessary for those pur

poses. Petitioners sought to present evidence in support

—8—

of that petition but the court refused to hear any such

evidence.

As soon as the deposit had been made with the County

Treasurer the school district sought by various means to

obtain possession of petitioners’ land. As early as De

cember 13, 1961, while the second appeal was pending in

the Illinois Supreme Court, the school district forcibly

took possession of the land, ousted petitioners and de

stroyed their produce business at the height of the season

of Christmas sales. After the opinion on that appeal was

issued but while the petition for rehearing was pending

in the Supreme Court of Illinois, the school district sought

in the Circuit Court of Cook County a supplemental writ

of possession to the land. After the petition for rehearing

was denied, that writ issued and the Circuit Court denied

the petition to vacate its judgment on October 4, 1962.

Petitioners appealed from that order.

Meanwhile, petitioners and 12 other taxpayers, resi

dents of the school district, sought leave to file a tax

payers’ complaint for an injunction restraining the school

district from taking petitioners’ land charging, on a

number of grounds, that the school district was proceed

ing in violation of the law. The Circuit Court of Cook

County denied leave to file the taxpayers’ suit. An appeal

was taken from that order. That appeal and the appeal

of the petitioners from the order of October 4, 1962, were

consolidated. In People ex rel. White, et al. v. Busenhart,

et al., 29 111. 2d 156, 193 N.E. 2d 850 (1963), the Circuit

Court of Cook County was affirmed in both cases. With

respect to the appeal of petitioners, the Illinois Supreme

Court said, 29 111. 2d 156, 159, 193 N.E. 2d 850, 853 (1963):

- 9 -

* # # # #

“In the eminent domain feature of this appeal the

Sehroeders seek to raise the following issues: (1)

That the court had no ‘jurisdiction’ to enter judgment

for the taking of a fee-simple title; (2) that the

property is exempt from condemnation because of its

location within 40 rods of the owners’ dwelling; (3)

that the ordinance (resolution) authorizing condem

nation was void for lack of a quorum at the time of

its passage; (4) that there was abandonment of the

project by failure to pay the award within 150 days

of October 27, 1960, as directed; and (5) that the

appeal bond was void.

“ [1-7] All of these points could have been raised

in the second appeal, in fact (2) above was conclu

sively adjudicated against the Sehroeders, and they

are now barred. The rule has long been recognized

that no point which was raised, or could have been

raised in a prior appeal on the merits, can be urged

on a subsequent appeal, and those not raised are

considered as waived. (Semple v. Anderson, 4 Gilm.

546; Union Mutual Life Ins. Co. v. Kirchoff, 149 111.

536, 36 N.E. 1031; Jackson v. Glos, 249 111. 388, 94

N.E. 502.) ‘Where an order or decree is reversed and

the cause is remanded by this court, with specific

directions as to the action to be taken by the trial

court, the only question properly presented on appeal

is whether the order or decree is in accordance with

the mandate and directions of this court.’ (People v.

National Builders Bank of Chicago, 12 111. 2d 473,

476-477, 147 N.E. 2d 42, 44.) Despite the rule, the

prayer of the petition for the taking of a fee-simple

title, and the failure to even include the question in

the traverse, the Sehroeders contend that it goes to

the jurisdiction of the court and can be raised either

directly or collaterally. In Chicago Housing Authority

v. Berkson, 415 111. 159, 112 N.E. 2d 620, the right of

the condemnor to acquire property by eminent domain

was questioned and alleged to be jurisdictional. It

—10—

was there said, 415 111. at pages 161 and 162, 112 N.E.

2d at page 621: * * (T)he objection was waived

by failure to raise it at the appropriate time. The

objection goes only to the right of the condemnor to

acquire property by eminent domain. It does not

affect the general jurisdiction of the court over the

subject matter of an eminent domain action.’ There,

the condemnor’s right to acquire by eminent domain

was attacked, while here only the extent of the estate

to be taken is alleged to be grounds for going behind

the judgment. We are of the opinion that the fee-

simple-title question is barred.” (Emphasis supplied.)

* * * * *

In light of the emphasized portion of the opinion of

the Supreme Court of Illinois a copy of the traverse and

the amendment thereto taken from the Abstract of Record

in the second appeal, Trustees of Schools of Township 42

v. Schroeder, supra, is appended hereto as Appendix D,

and this Court is respectfully urged to take judicial notice

of that traverse.

No petition for certiorari to this Court was filed seeking

review of either of the two decisions by the Supreme

Court of Illinois adverse to petitioners. Instead the com

plaint in the instant case was filed about two months

after the denial of a petition for rehearing by the Illinois

Supreme Court in that last appeal.

In the fall of 1962 the school district built a small inter

mediate grade school on one-quarter acre of the 18 acre

tract taken from petitioners. The school building is lo

cated the maximum distance from the Rand Road front

age which is not being used for a school or school

purposes.

- 1 1 -

In their complaint in this cause petitioners sought a

declaratory judgment that the taking of a fee simple title

to their land denied due process of law to petitioners and

that the judgments of the Circuit Court of Cook County

awarding the land to the school district were void and

that the mandate of the Supreme Court of Illinois in the

last appeal was void. In addition, the petitioners prayed

an injunction restraining the respondents and their agents,

etc., from claiming ownership of the land or interfering

with the petitioners as the rightful owners and restraining

defendants from interfering with the fund in the custody

of the county treasurer.

REASONS RELIED ON FOR ALLOWANCE

OF A WRIT OF CERTIORARI.

In this cause the Court of Appeals has decided a fed

eral question in a way which is in conflict with applicable

decisions of this Court and has so far sanctioned such a

departure by the district court from the usual and ac

cepted course of judicial proceedings as to call for an

exercise of this Court’s power of supervision.

- 1 2 -

ARGUMENT.

It is fundamental to our system of private ownership

of property that government, neither federal, state nor

local, may take private property save for public use and

then, only upon payment of just compensation. It is equally

fundamental to our system of ordered liberty that the

courts, both state and federal, provide protection for

those rights of private property. In this case, despite

their continuous efforts, petitioners have been denied that

protection by both state and federal courts. Indeed, in

this case the courts, both state and federal, have refused

to hear petitioners assertions as to their property rights.

Basically petitioners contend, and have sought to do so

throughout tortuous litigation, that the school district has

taken their property but not for public use and that, in

any event, the school district has taken more of their

property, both in quantity and in extent of title, than

was justified for any public use. Petitioners owned 18

acres of highly valuable, well-located, land in a rapidly

developing suburban area. Without contradiction, the

record here shows that nearly five years after the school

district took fee simple title to all 18 acres, the school

district has used only one-quarter of one acre of the tract

at the back end leaving untouched and unused the remain

ing 17 acres including the obviously more valuable Rand

Road frontage (App., pp. 78-80). The law of Illinois is

clear that this school district had no power to take fee

simple title by eminent domain. See Kelly, et al. v.

Bowman, et al., 104 F. Supp. 973 (E.D. 111. 1952); aff’d

202 F. 2d 275, 276 (C.A. 7th 1953). In that case, the Court

of Appeals flatly stated:

“Judge Casper Platt, by whom the case was tried,

filed an opinion, Kelly v. Bowman, D.C., 104 F. Supp.

973, which contains an adequate statement of the

facts, as well as a thorough analysis of the appli

cable Illinois law. Inasmuch as we agree with the

result which he reached, as well as the reasoning

upon which it is predicated, we think no good pur

pose could be served in writing an opinion. We there

fore adopt the opinion of Judge Platt as that of this

court.” # # # # #

Significantly, in none of its opinions involving this

land has the Illinois Supreme Court questioned the propo

sition that the school district had no power to take a

fee simple title. Instead the Illinois Supreme Court has

steadfastly refused even to consider the question. The

only justification which that Court has offered for its

refusal to consider this deprivation of petitioners’ rights

is found in People ex rel White v. Busenhart, supra. That

justification, strangely enough, is that the issue was not

raised in the traverse. Obviously the Illinois Supreme

Court was mistaken with respect to that fact (see Ap

pendix D, this petition). Equally, the Illinois Supreme

Court was mistaken in its assertion that the issue was

not raised on the so-called second appeal. It was raised

by the petition for rehearing and apparently ignoredJ1)

(x) It is the practice of the Illinois Supreme Court

to issue printed copies of its opinion to the parties upon

the filing of the opinion with the Clerk of that Court.

If a petition for rehearing is filed the Court may with

draw the opinion, modify the opinion, or leave it un

changed if the rehearing is denied. In Trustees of Schools

of Township 42, etc. v. Schroeder, supra, the second ap

peal, the original opinion issued May 25, 1962, remained

•14—

Thus, in the instant case, petitioners sought to present

to the district court a plea for federal remedy in a case

where it was alleged and uncontradicted, that state offi

cials had taken more of petitioners’ land than the state

officials had any authority so to do and that they had

taken more of the title than they had any authority so

to do.

It seems never to have been doubted in this Court that

the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits state officers from

expropriating privately-owned land just as the Fifth

Amendment prohibits federal officers from taking land

from private owners. In City of Cincinnati v. Vester, 281

U.S. 439, 446-447 (1930), then Chief Justice Hughes, in

an “excessive condemnation” case pointed out:

■u. O -V- -*1*7T W W W W

“It is well established that, in considering the ap

plication of the Fourteenth Amendment to cases of

expropriation of private property, the question what

is a public use is a judicial one. In deciding such a

question, the Court has appropriate regard to the

diversity of local conditions and considers with great

respect legislative declarations and in particular the

judgments of state courts as to the uses considered

to be public in the light of local exigencies. But the

question remains a judicial one which this Court

must decide in performing its duty of enforcing the

provisions of the Federal ConstitutionJ1) In the pres

ent instance, we have no legislative declaration, apart

unchanged and the petition for rehearing was denied

on September 27, 1962. It thus appears that while the

Illinois Supreme Court had before it the issue of the

power of the school district to take title by eminent do

main to the whole of the 18 acres, that Court never in

dicated its ruling as to the issue or any basis for such

a ruling.

—15—

from the statement of the city council, and no judg

ment of the state court as to the particular matter

before us. Under the provision of the Constitution of

Ohio for excess condemnation when a city acquires

property for public use, it would seem to be clear

that a mere statement by the council that the excess

condemnation is in furtherance of such use would

not be conclusive. Otherwise, the taking of any land

in excess condemnation, although in reality wholly

unrelated to the immediate improvement, would be

sustained on a bare recital. This would be to treat the

constitutional provision as giving such a sweeping

authority to municipalities as to make nugatory the

express condition upon which the authority is

granted.” (Footnote omitted.)

# * # * *

The cases cited in the omitted footnote are all to the

same effect.

More recently in County of Allegheny v. Frank Ma-

shuda Company, 360 U.S. 185 (1959), this Court affirmed

a decision of the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

that a district court was in error in dismissing a com

plaint by a land owner who contended that his land had

been taken by a county board for private not public use.

In that case, just as in this one, the district court had

refused to exercise the jurisdiction vested in it by the

Judiciary Act because the district court believed that

there was a threat to state-federal relationships in the

exercise of such jurisdiction. This Court, however, found

no justification for “abstention” from the exercise of

federal jurisdiction in the suit of the land owner who

complained that his property was taken for private use.

Ironically, in the Mashuda case, supra, it was agreed

that the land owner had a remedy in the Pennsylvania

state courts to raise the issue which he sought to raise

—16-

in the federal court. In the instant case petitioners have

no such remedy in the state court. In fact, despite their

unremitting efforts to secure a state court remedy, the

Illinois courts have emphatically refused to provide a

remedy.

This Court has repeatedly made it clear that state judi

cial action may itself violate the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. Appropriately,

the leading decisions in that respect involve the rights

of land owners. See Shelly v. Kramer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948);

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953), and Hansberry

v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940). The Hansberry case, supra,

makes it clear that where the state court, as here, has

refused to consider the merits of constitutional claims,

property owners are denied procedural due process as

well as substantive due process.

In the instant case petitioners invoked the jurisdiction

of the district court on dual grounds. The complaint relied

upon 28 U.S.C., §§ 1331(a) and 1343(3). By amendment,

with leave of court (App., p. 35), the complaint alleged that

the amount involved exceeds $10,000 and that federal and

constitutional questions were involved. Accordingly, the

complaint plainly stated a cause of action under 28 U.S.C.,

§ 1331(a). The Court of Appeals, however, was apparently

of the opinion that no federal question could be presented

because “the state court admittedly had jurisdiction over

the parties and the subject matter. * * That holding,

we respectfully submit is entirely inconsistent with the

views expressed by this Court in Shelly v. Kramer, supra,

Barrows v. Jackson, supra, and Hansberry v. Lee, supra.

In all of those cases the state court also had jurisdiction

of the parties and of the subject matter. Nevertheless this

Court ruled that the state judicial action itself violated

■17

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States. We respectfully suggest that this is pre

cisely the situation here.

The view of the Court of Appeals in the instant case

is plainly inconsistent with respect to the scope of federal

jurisdiction voiced in McGuire v. Sadler, 337 F. 2d 902,

906 (C.A. 5th 1964). In that case the court observed:

-SI.~7' 'A' W

“Quite apart from the question of impairment of

contract, the plaintiff’s Fourteenth Amendment claim

stands on its own feet. There is no question that

there was state action for the purpose of invoking

the Fourteenth Amendment. Monroe v. Pape, 1961,

365 U.S. 167, 81 S.Ct. 473, 5 L.Ed. 2d 492; Hornsby

v. Allen, 5 Cir. 1964, 326 F. 2d 605. And there is de

privation of property—if we accept plaintiff’s allega

tions. The fraud of the Commissioner, if a fact, would

be enough to require the nullification of his findings

and subsequent action. In addition, the plaintiff al

leges various procedural shortcomings in the state

proceedings. He alleges that he was denied the time

and access to information needed in order to defend

his interest; that the Commissioner and the co-con

spirators used various unfair stratagems during the

hearing in order to prevent his being heard; that the

Commissioner was present at the hearing for only

a few minutes, which resulted in a clerk’s (the Chief

Clerk’s) conducting the hearing. If such procedural

shortcomings are found to have existed and if indeed

they deprived the plaintiff of a fair and adequate

hearing, these findings wTould seem sufficient for a

showing of a Fourteenth Amendment violation.

“ [9] The plaintiff also invokes the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. He em

ploys the words ‘fraudulent’ and ‘wilful’ not just op-

probriously but to show allegedly purposeful discrim

ination. The allegations of fraudulent and diserim-

— 18—

inatory official action are made with specificity so as

to bring the plaintiff within even the conservative

definition of equal protection announced in Snowden

v. Hughes, 1944, 321 U.S. 1, 64 S.Ct. 397, 88 L.Ed.

497. See also Hornsby v. Allen, 5 Cir. 1964, 326 F. 2d

605.”

# # * # #

Both that decision and Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167

(1961), make it clear that in addition to invoking the

jurisdiction of the district court in this cause under

§ 1331, petitioners also properly invoked the jurisdiction

of the district court under 28 U.S.C., § 1343(3). Peti

tioners alleged both acts of state officials, the school dis

trict, state courts and the county treasurer in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment. They also charged a con

spiracy between those state officers and private persons,

petitioners’ former counsel, to deprive them of equal pro

tection of the laws as well as other rights guaranteed by

the Constitution of the United States. At this term this

Court in United States v. Price, ..... U.S....... , 86 S. Ct.

1152 (1966), made it clear that joint participation of

private persons and state officials in prohibited conduct

is action “under color” of law within the meaning of the

Civil Rights Act.

Thus, the dismissal of the complaint in this cause denied

to petitioners access to the federal courts provided for

under two sections of the Judicial Act.

The real ground for denying a federal remedy to peti

tioners appears to have been the state court decisions.

It is clear from the record in this case, however, that the

state courts have never considered the federal issues in

volved here. It is equally clear that the decisions of this

Court do not warrant denial of federal protection for

federal constitutional rights because a state court has

— 19—

refused to consider the questions. Ironically, the leading

cases on this point are cases in which this Court has re

quired lower federal courts to consider claims of federal

constitutional rights in criminal cases. See e.g., Town

send v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293 (1963). We respectfully submit

that the rights of land owners are entitled to the same

protection from unlawful acts by state officials as is the

liberty of persons charged with crime.

CONCLUSION.

For all of the foregoing reasons we respectfully urge

this Court to issue its writ of certiorari to review the

decision of the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

in this matter. In this period of wide-spread use of the

power of eminent domain by federal, state and local offi

cials, it is imperative for the protection of all persons in

the United States that it be made clear that the law of

the United States does not permit unconscionable abuse

of the power of eminent domain by government officers.

Respectfully submitted,

W illiam R. Ming, J r.,

H elen I. Cohen,

123 West Madison Street,

Chicago, Illinois 60602,

FRanklin 2-1106,

J ohn J . H oellen,

1940 W. Irving Park Road,

Chicago, Illinois 60613,

Attorneys for Petitioners.

APPENDIX A

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the Seventh Circuit

September T eem, 1965—September Session, 1965

No. 14920

Gerald A. Schroeder and

Clara J ohnson Schroeder,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

State op I llinois, Bernard J.

K orzen, County Treasurer of

Cook County, T rustees of

Schools of Township 42 North,

Range 11, East of the Third

Principal Meridian, Cook

County, Illinois, for the use and

benefit of Board of E ducation,

School District 57, Cook County,

Illinois, W ilbert J. J. W ahler

and Daniel W. P ecyna,

Defendants-Appellees. _

>

A p p e a l from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Northern District

of Illinois, Eastern

Division.

November 2, 1965

-2 a -

Before H astings, Chief Judge, K noch and K iley,

Circuit Judges.

K iley, Circuit Judge. This suit invoked the district

court’s jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. $ 1331 and § 1343(3) l1 * 3)

for declaratory judgment and injunctive relief based on

alleged violation of the Reconstruction era Civil Rights

Act, presently sections 1981 to 1985 of Title 42, United

States Code. The district court dismissed for want of

jurisdiction. We affirm.

Plaintiffs, Gerald and Clara Sehroeder, were owners of

17.78 acres of land in Mount Prospect, Illinois, in Novem

ber, 1959, when defendant-Trustees filed suit in the Cir

cuit Court of Cook County to condemn the property for

school purposes. A jury’s verdict awarded the Sehroeders

$267,083.33, and judgment was entered on the verdict. The

Circuit Court ordered a new trial, but this order was

reversed on appeal. Trustees of Schools v. Sehroeder, 23

111. 2d 74, 177 N.E. 2d 178 (1961). On remand the Circuit

Court entered judgment in the amount of the jury’s ver

dict, plus interest and costs, for a total of $280,956.10, and

(U. 8. Court of Appeals Opinion)

(1) 28 U.S.C. § 1331 provides for federal question juris

diction.

28 U.S.C. § 1343(3):

The district courts shall have original jurisdiction

of any civil action authorized by law to be commenced

by any person: # # #

(3) To redress the deprivation, under color of any

state law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or

usage, of any right, privilege or immunity secured by

the Constitution of the United States or by any Act

of Congress providing for equal rights of citizens or

of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States; * * *

— 3a-

ordered that upon payment or deposit of that sum with

the Cook County Treasurer, fee simple title would vest in

the Trustees. The sum being deposited, the court declared

fee simple title to be in the Trustees and authorized them

to take possession. An appeal from this judgment resulted

in affirmance, Trustees of Schools v. Schroeder, 25 111. 2d

289, 184 N.E. 2d 872 (1962), and rehearing was denied.

Schroeders then filed in the Circuit Court motions to

vacate the judgment vesting title in the Trustees, and

Schroeders and others moved for leave to file a taxpayers’

suit to enjoin execution on the condemnation judgment.

The motions were denied and the Illinois Supreme Court

affirmed these rulings. People ex rel White v. Busenhart,

29 111. 2d 156, 193 N.E. 2d 850 (1963). Rehearing was

denied and no petition for certiorari to the United States

Supreme Court was filed. The suit before us followed.

We see no necessity of discussing sections 1981 and

1982 of Title 42, which are plainly designed to implement

the fourteenth amendment by providing equal rights for

negroes. Agnew v. City of Compton, 239 F. 2d 226, 230 (9th

Cir. 1956). This case rests upon allegations of individual

violations of section 1983 <2) and conspiratorial violations

of section 1985(2).

(U. 8. Court of Appeals Opinion)

(2> 42 U.S.C. § 1983:

Every person who, under color of any statute, or

dinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State

or Territory, subjects, or causes to he subjected, any

citizen of the United States or other person within

the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Con

stitution and laws, shall be liable to the party in

jured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other

proper proceeding for redress.

---- 4 U ’

The complaint alleges that the defendant-Trustees and

their attorneys conspired, at the hearing upon the motion

to vacate the condemnation judgment, to deprive Schroe-

ders of their “rights and privileges” and due process in

violation of section 1985(2). The only facts alleged to

support the general allegations are that plaintiffs, by vir

tue of the conspiracy, were deprived of their “right to

present evidence consisting of oral testimony, exhibits and

written documents ’ ’ in support of their petition in the Cir

cuit Court to vacate the judgment entered against them.

It appears from the record that the Circuit Court denied

them this “right” after the Illinois Supreme Court in the

second appeal, opinion at 25 111. 2d 289, 184 N.E. 2d 872,

had affirmed the very judgment the petitioners sought to

have the Circuit Court vacate. There is no allegation of

(U. 8. Court of Appeals Opinion)

(3) 42 U.S.C. § 1985(2):

If two or more persons in any State or Territory

conspire to deter, by force, intimidation, or threat,

any party or witness in any court of the United States

from attending such court, or from testifying to any

matter pending therein, freely, fully, and truthfully,

or to injure such party or witness in his person or

property on account of his having so attended or

testified, or to influence the verdict, presentment, or

indictment . . .; or if two or more persons conspire

for the purpose of impeding, hindering, obstructing,

or defeating, in any manner, the due course of jus

tice in any State . . ., with intent to deny to any

citizen the equal protection of the laws, or to injure

him or his property for lawfully enforcing, or at

tempting to enforce, the right of any person, or class

of persons, to the equal protection of the laws; * * *

We presume Schroeders are relying on § 1985(2) in

this respect since it is clear that § 1985(1) and (3) have

no application to their suit.

-5 a-

conspiracy to interfere with, or injure any Sehroeder wit

ness; none of deprivation of equal protection of the law;

and none that these defendants were acting under color

of state law. Thus no claim was presented under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1985(2) and 28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) upon which jurisdiction

could be based, and no federal question arises under the

fourteenth amendment to confer § 1331 jurisdiction.

Most of the complaint is devoted to the claim that the

Schroeders were deprived of their fee title without due

process because the Circuit Court at the trial ordered that

the Trustees acquired a fee simple title in Schroeders’

property, and the Illinois Supreme Court affirmed the

order, all allegedly without authority in law. They allege

that Illinois statutory and decisional law limited the au

thority of the courts, on the facts of the condemnation

case, to transferring of an easement for school purposes,

leaving Schroeders a reversionary interest. The claim

is that the Illinois court decisions in this ease deprived

them of due process under the fifth and fourteenth amend

ments, and that if execution upon the condemnation judg

ment is made and if defendants are permitted to take and

hold possession of the fee title Schroeders will further

be denied due process.

The relief sought is a declaration that the Illinois court

decisions, in proceedings at trial and on review, are void

even though the courts had jurisdiction of the subject

matter and parties. These allegations, even if true, do not

present either a ground for federal question jurisdiction

under 28 U.S.C. § 1331, since the state court admittedly

had jurisdiction over the parties and the subject matter,

Chance v. County Board of School Trustees, 332 F. 2d 971,

(TJ. 8. Court of Appeals Opinion)

— 6a—

974 (7th Cir. 1964); or a ground upon which to obtain

review of the state court proceedings by a federal district

court under 28 U.S.C. § 1343 through invocation of 42

U.S.C. § 1983, Goss v. State of Illinois, 312 F. 2d 257, 259

(7th Cir. 1963). Schroeders attempt “to thwart” the final

state court judgments by relitigating in a trial de novo the

very issues wdiieh were, or should have been, raised in

the state courts concerning state law, and upon which cer

tiorari to the United States Supreme Court might have

been sought. To paraphrase what was said in Goss about

permitting such “appellate procedure,” if it were done

many state court judgments would be faced with chaos

and unenforceability. 312 F. 2d at 259. Thus there is also

no independent ground for jurisdiction to enter a declara

tory judgment under 28 U.S.C. ■§ 2201.

The injunctive relief sought against state officials from

enforcing the condemnation judgment, and against the

Trustees from taking possession under their fee title, pre

supposes a declaration that the decisions of the Illinois

judges in the Schroeder condemnation ease are void. The

same is true of the relief sought against defendant Kor-

zen, County Treasurer, custodian of the funds due Schroe

ders. And no allegation of any violation of Schroeders’

civil rights is made against defendants Wahler and Pe-

cyna, their former attorneys.

For the reasons given, the judgment is affirmed.

A true Copy:

Teste:

(U. S. Court of Appeals Opinion)

Clerk of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

A PPEN D IX B

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS INVOLVED.

Fifth Amendment, United States Constitution:

“No person shall be held to answer for a capital,

or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a present

ment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases

arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia,

when in actual service in time of War or public dan

ger ; nor shall any person be subject for the same of

fence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor

shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a wit

ness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty,

or property, without due process of law; nor shall

private property be taken for public use, without

just compensation.”

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution provides in pertinent part:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are

citizens of the United States and of the State where

in they reside. No State shall make or enforce any

law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities

of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State

deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, with

out due process of law; nor deny to any person within

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

A PPE N D IX C

STATUTES INVOLVED.

28 U.S.C., § 1331(a). Federal question; amount in con

troversy.

The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of

all civil actions wherein the matter in controversy ex

ceeds the sum or value of $10,000, exclusive of interest

and costs, and arises under the Constitution, laws, or

treaties of the United States.

28 U.S.C., § 1343(3). Civil rights and elective franchise.

To redress the deprivation, under color of any State

law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage, of

any right, privilege or immunity secured by the Consti

tution of the United States or by any Act of Congress

providing for equal rights of citizens or of all persons

within the jurisdiction of the United States.

42 U.S.C., § 1981. Equal rights under the law.

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States

shall have the same right in every State and Territory to

make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evi

dence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and

proceedings for the security of persons and property as

is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like

punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions

of every kind, and to no other. R.S. § 1977.

—9a-

42 U.S.C., § 1982. Property rights of citizens.

All citizens of the United States shall have the same

right, in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white

citizens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and

convey real and personal property. E.S. § 1978.

42 U.S.C., § 1983. Civil action for deprivation of rights.

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Terri

tory, subjects, or cause to be subjected, any citizen of the

United States or other person within the jurisdiction

thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or

immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall

be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit

in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress. R.S.

§ 1979.

42 U.S.C., § 1985. Conspiracy to interfere with civil rights

—Preventing officer from performing duties.

(1) If two or more persons in any State or Territory

conspire to prevent, by force, intimidation, or threat, any

person from accepting or holding any office, trust, or place

of confidence under the United States, or from discharging

any duties thereof; or to induce by like means any officer

of the United States to leave any State, district, or place,

where his duties as an officer are required to be per

formed, or to injure him in his person or property on

account of the lawful discharge of the duties of his office,

or while engaged in the lawful discharge thereof, or to

injure his property so as to molest, interrupt, hinder, or

impede him in the discharge of his official duties;

(Statutes Involved)

— 10a—

Obstructing justice; intimidating party, witness, or juror.

(2) If two or more persons in any State or Territory

conspire to deter, by force, intimidation, or threat, any

party or witness in any court of the United States from

attending such court, or from testifying to any matter

pending therein, freely, fully, and truthfully, or to injure

such party or witness in his person or property on account

of his having so attended or testified, or to influence the

verdict, presentment, or indictment of any grand or petit

juror in any such court, or to injure such juror in his

person or property on account of any verdict, present

ment, or indictment lawfully assented to by him, or of his

being or having been such juror; or if two or more per

sons conspire for the purpose of impeding, hindering,

obstructing, or defeating, in any manner, the due course

of justice in any State or Territory, with intent to deny

to any citizen the equal protection of the laws, or to injure

him or his property for lawfully enforcing, or attempting

to enforce, the right of any person, or class of persons,

to the equal protection of the laws;

Depriving persons of rights or privileges.

(3) If two or more persons in any State or Territory

conspire or go in disguise on the highway or on the prem

ises of another, for the purpose of depriving, either di

rectly or indirectly, any person or class of persons of the

equal protection of the laws, or of equal privileges and

immunities under the laws; or for the purpose of pre

venting or hindering the constituted authorities of any

State or Territory from giving or securing to all persons

within such State or Territory the equal protection of

(Statutes Involved)

■11a

the laws; or if two or more persons conspire to prevent

by force, intimidation, or threat, any citizen who is law

fully entitled to vote, from giving his support or advocacy

in a legal manner, toward or in favor of the election of

any lawfully qualified person as an elector for President

or Vice President, or as a Member of Congress of the

United States; or to injure any citizen in person or prop

erty on account of such support or advocacy; in any case

of conspiracy set forth in this section, if one or more

persons engaged therein do, or cause to be done, any act in

furtherance of the object of such conspiracy, whereby

another is injured in his person or property, or deprived

of having and exercising any right or privilege of a

citizen of the United States, the party so injured or de

prived may have an action for the recovery of damages,

occasioned by such injury or deprivation, against any one

or more of the conspirators. R.S. § 1980.

(Statutes Involved)

— 12a—

APPENDIX D

Traverse filed by Gerald A. Schroeder and Clara John

son Schroeder, respondents, filed December 4, 1959, which

is as follows:

(Title, signatures and verification not abstracted.)

Now comes the respondents, Gerald A. Schroeder, and

Clara Johnson Schroeder, by their attorneys, Wahler &

Pecyna, and traverses, denies and controverts the peti

tioner’s right to condemn, and calls for strict proof of

the following matters alleged in the petition:

1. Denies that the Trustees of Schools of Township

42, North Range 11, East of the Third Principal Me

ridian, Cook County, Illinois, are, by the “School Code”

of the State of Illinois, effective May 1, 1945, and as

subsequently amended, authorized or empowered to ac

quire by eminent domain proceedings, or otherwise, or to

hold for the benefit of the School Districts of said town

ship, lands necessary for school purposes.

2. Denies that School District Number 57, Cook County,

Illinois, is a duly organized or established or an existing

school district located in Township 42, North Range 11,

East of the Third Principal Meridian, Cook County, Illi

nois.

3. Denies that said School District, as alleged in the

petition, is governed by a Board of Education pursuant

to the provisions of the school code of the State of Illinois.

4. Denies that in accordance with the provisions of

the school code of the State of Illinois, that the Board

of Education, School District Number 57, Cook County,

— 1 3 a

( Traverse)

Illinois, passed a resolution to acquire a fee simple title

by purchase or condemnation or otherwise the following

described real estate, to wit:

That part of the South half (y2) of the Southeast

Quarter (1 4 ) of the Northeast quarter (%) of Sec

tion 34, Township 42, North Range 11, East of the

Third Principal Meridian lying Westerly of the

Center line of Rand Road

also

That part of the North half (y2) of the Southeast

Quarter (%) of the Northeast Quarter of Section 34,

Township 42, North Range 11, East of the Third

Principal Meridian lying Westerly of the center line

of Rand Road, except the North 138 feet thereof.

5. Denies that the purpose of acquiring said real

estate is to provide necessary school facilities in connec

tion with the schools of said district.

6. Denies that a fair and reasonable cash offer has

been made for said property to the owners thereof, and

asserts that the offer made was wholly unfair and un

reasonable.

7. Denies that petitioner has any right or power under

and by virtue of the school code of the State of Illinois,

effective May 1, 1945, and as subsequently amended to

condemn said property as alleged in said petition, or

that the said property, as alleged in said petition, lies

wholly within School District Number 57, Cook County,

Illinois.

8. Denies that this proceeding is valid.

9. Denies that the petitioner has taken each and every

one of the necessary steps required to be taken in a con-

— 1 4 a -

(Tr averse J

demnation proceeding of the property described in the

petition filed herein.

10. Denies that the petitioner has any legal right to

condemn the property described in said petition or any

part thereof.

11. Denies that the purpose of acquiring said real

estate is to provide necessary school facilities, in whole

or in part, and asserts that the property described in

said petition is wholly in excess of that which is necessary,

and further asserts that either all or a part thereof is

for purposes or uses other than school facilities.

12. Denies that the petitioner has been authorized to

acquire, hold and use the aforesaid property as described

in the petition for the purposes or uses described in the

petition, and asserts that the petitioner is acquiring said

property by condemnation to hold and use for purposes

other than necessary school facilities and for purposes

and uses which are not authorized by statute.

13. Denies that a lawful and valid resolution was

passed by the Board of Education, School District Num

ber 57, Cook County, Illinois, authorizing the condemna

tion of purchase of the property described in said petition.

14. Denies that any reasonable or fair plan or scheme

has been arrived at, prepared or analyzed by the Board

of Education, School District Number 57, Cook County,

Illinois, regarding the schools in said district; or that a

fair and reasonable plan or scheme as to the future needs

of said district has been presented to it and considered.

15. Denies that the compensation to be paid by the peti

tioner for the said property described in the petition

15a-

( Traverse)

cannot be agreed upon between the petitioner and the

respondents, Gerald A. Schroeder and Clara Johnson

Schroeder, and each of them, since no fair and reasonable

offer had been submitted to them.

16. Denies that the purported use of the property by

the petitioner has been determined upon definitely, and

irrevocably, for the sole and exclusive purpose of provid

ing schools presently or in the future for said district;

and further denies that any degree of certainty exists for

the purported use of property in the future.

17. Respondents further say that the area of land as

described in said petition, sought to be acquired by con

demnation, is grossly excessive for use as a school or

for school purposes, and said taking in whole or in part

is unnecessary.

18. Respondents further say that the action herein is

arbitrary, capricious, unnecessary, and wholly without the

authority of the Board of Education, School District

Number 57, Cook County, Illinois, or the Trustees of

Schools, Township 42, North Range 11, East of the Third

Principal Meridian, Cook County, Illinois.

19. Denies that said tract, described in petitioner’s

Petition to Condemn, is convenient and useful for the

purported intended purposes of schools, and respondents

say that there are other tracts more convenient and use

ful for the purported intended purpose.

20. Respondents say that the land in question is lo

cated in a highly congested area, on a main arterial high

way, which carries tremendous traffic at high speed, and

that placing a school or schools thereon is highly dan-

— 1 6 a —

(Traverse)

gerous to the children in said district, having in mind

the area, location and use of way.

Wherefore, your respondents, Gerald A. Schroeder and

Clara Johnson Schroeder, and each of them, respectfully

pray that said petition be stricken and dismissed, and all

costs be taxed to the petitioner.

Amendment to traverse filed by Gerald A. Schroeder

and Clara Johnson Schroeder, respondents, on May 13,

1960, which is as follows:

Now comes Gerald A. Schroeder and Clara Johnson

Schroeder by Wahler & Pecyna, their attorneys, and by

leave of Court first had and obtained, files their Amend

ment to their Traverse heretofore filed herein by adding

additional Paragraphs thereto numbered 21, 22 and 23,

which are as follows:

21. Respondents further say that the area of land, as

described in said Petition sought to be acquired by con

demnation is farm land and that all of said property lies

outside of the City or Village limits of Mount Prospect

or any incorporated City or Village; Respondents further

say that their dwelling, house, residence and home is

located and situated upon the area of land, as described

in said Petition and that all or at least the majority of

the property sought to be condemned by the petitioners

is within 40 rods of the dwelling of the respondents and

owners of the land mentioned in the Petition and sought

to be condemned by the Petitioners.

And further deny that the petitioners have any right

or power under and by virtue of The School Code of the

State of Illinois, effective May 1, 1945, and as subse-

— 17a-

(Tr averse)

quently amended to condemn all or any part of said prop

erty, as alleged in said Petition by reason of the afore

said facts.

22. The Respondents again specifically deny that the

Petitioners have any right or power under and by virtue

of The School Code of the State of Illinois, effective May

1, 1945 and as subsequently amended to condemn any

part or all of said property, as alleged in said Petition

and affirmatively plead and show unto the Court that

under the facts, as alleged in Paragraph 21 herein, the

area mentioned in whole or in part is, by Statute, ex

cluded from condemnation by virtue of Section 14-7 of

The School Code of Illinois, Chapter 122 of the Smith -

Hurd Illinois Annotated Statutes, which specifically pro

vides that no tract of land outside the limits of any in

corporated City or Village and within 40 rods of the

dwelling of the owner shall be taken by the Board of

Directors without the owner’s consent.

23. Respondents further say that they do not consent

to the condemnation or taking of any part or all of the

area described in the Petition and which they are the

owners of; and further plead and say that Section 14-7

of The School Code specifically denies and controverts

the Petitioners’ right to condemn the area alleged in the

Petition and further by reason of the hereinabove men

tioned facts; Section 14-7 of The School Code of Illinois,

Chapter 122, Smith-Hurd Illinois Annotated Statutes,

provides as follows:

“Whenever any lot or parcel of land is needed by

any university, college, township high school or other

educational institution established and supported by

— 18a-

(Traverse)

this State or by a township therein, or by a school

district, as a site for a building or for any educa

tional purpose, and compensation for the lot or parcel

of land cannot be agreed upon between the owners

thereof and the trustees, board of education, or other

corporate authority of the educational institution or

school district, the corporate authority of the educa

tional institution or school district may have the com

pensation determined in the manner provided by law

for the exercise of the right of eminent domain. In

Class I counties, the school board shall engage counsel,

pay all expenses and institute suit without any au

thorization by the county board of school trustees;

and the proceedings shall be in the name of the county

board of school trustees for the use of the school

district. But no tract of land outside the limits of

any incorporated city or village and within 40 rods

of the dwelling of the owner of the land shall be taken

by the board of directors, created in Article 6, with

out the owner’s consent; provided, however, that a

tract of land outside the limits of any incorporated

city or village lying not less than 200 feet from the

dwelling of the owner of the land, which adjoins

and is adjacent to a school site being used for school

purposes may be taken by the board of directors in

the manner provided by law for the exercise of the

right of eminent domain for the purpose of enlarging

such school site for educational and recreational pur

poses.”