Order Approving Etowah County Settlement on Interim Basis

Public Court Documents

October 14, 1986

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Order Approving Etowah County Settlement on Interim Basis, 1986. 0eaf6cad-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/988358a4-273d-49b1-9795-aa54cbb78785/order-approving-etowah-county-settlement-on-interim-basis. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

% SS ; / 7 2

~D [ / / Ly / <<) /

\ = ny /) ‘7 £2 f

0 Xe / 5 ef Zz / 7/7 CC «

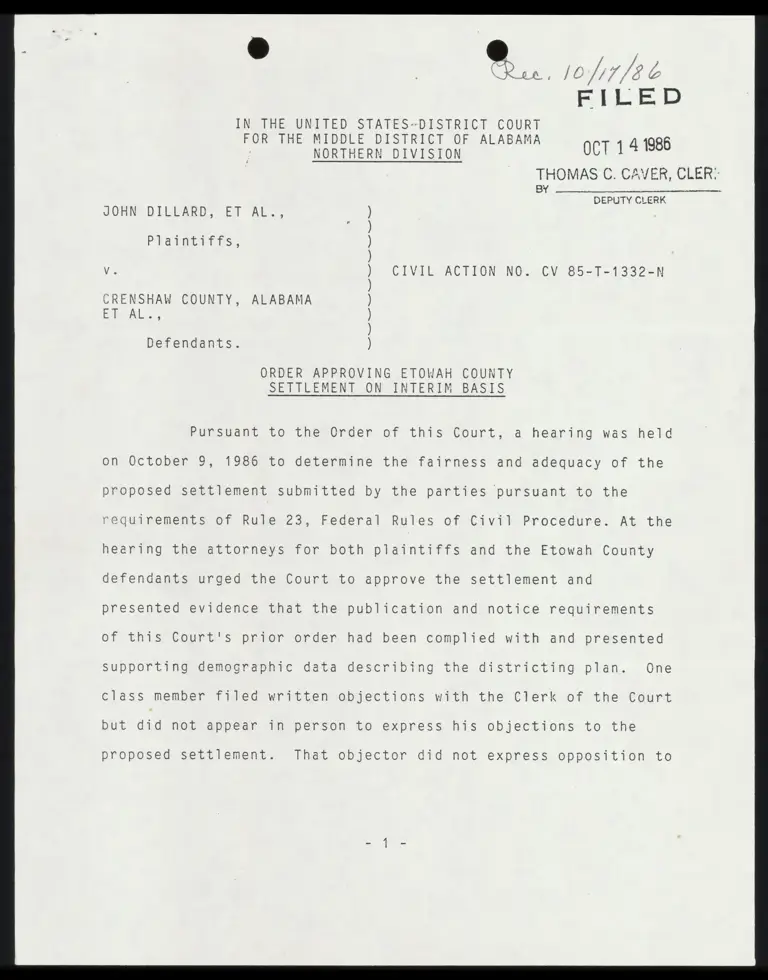

IN THE UNITED STATES-DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION OCT 141986

BY

DEPUTY CLERK

JOHN DILLARD, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

vs CIVIL ACTION NO. CV 85-T-1332-M

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA

ET- AL .,

N

a

a

t

?

N

e

a

t

N

a

a

t

?

e

e

e

?

e

e

t

?

a

a

c

e

e

e

e

t

?

e

e

?

Defendants.

ORDER APPROVING ETOWAH COUNTY

SETTLEMENT ON INTERIM BASIS

Pursuant to the Order of this Court, a hearing was held

on October 9, 1986 to determine the fairness and adequacy of the

proposed settlement submitted by the parties pursuant to the

requirements of Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. At the

hearing the attorneys for both plaintiffs and the Etowah County

defendants urged the Court to approve the settlement and

presented evidence that the publication and notice requirements

of this Court's prior order had been complied with and presented

supporting demographic data describing the districting plan. One

class member filed written objections with the Clerk of the Court

but did not appear in person to express his objections to the

proposed settlement. That objector did not express opposition to

the relief afforded the class but dished that the district dines

be changed to include his home in a.-different commission

district. The objector does not contend the proposed settlement

is not fair for the class. There is no basis in law or fact for

making a change to accomodate such an objection.

The Court finds that the requirements of Rule 23,

Fed.R.Civ.P., concerning notice to the class have been met and

that the proposed settlement is fair, Just and equitable. Cotton

Vv... Ainion, 55% F.2d 1326 (5th Cir. 19772): Holmes v,. Lontinental

Can Co., 706 F.2d 4144 {1%th Civ, 1983): Lurns v. Russell Lorp.,

607. F. Supp. 9338 (N.B. Ala. 1884). However, the Court will not,

at this time, give final approval to the proposed settlement

since it has not yet been precleared by the Department of

Justice, pursuant to ‘the. provisions of Section sb of the Yotling

Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.L. section. .1973¢c. McDaniel v.

Sanchez, 452 Y4.S. 130 (1981. The defendant Etowah County has

submitted the settlement for preclearance to the Department of

Justice but has not yet received a response. The defendant

Etowah County is cairected to request expedited consideration from

the Department of Justice and the Court expresses its desire that

the Department of Justice reach a determination on this matter at

the earliest practicable date.

The defendant Etowah County shall promptly notify this

Court of the determination of the Department of Jutice. If this

~ E

plan is precleared by the Department of Justice, the Court will

Issue an order finally approving the settlement. In the event

that the Department of Justice objects to the proposed plan, the

Court will allow the parties an opportunity to make a further

submission to the Department of Justice in an attempt to cure the

objections.

Party primary elections are scheduled for November 4,

1986, with any necessary runoffs to be held on November 25, 10986.

A special general election will be held December 16, 1986.

Election officials are in the process of arranging for the

conduct of party primary elections. The Court determines that

even though this plan should not be approved as a final plan

until the Department of Justice has precleared the plan, the

Court determines that the plan should be implemented as the

Court's own interim plan for the conduct of the imminent primary

glections. Unham v. Seanon, 456 U.S. 37 (1882): Burton v,.

Hobbie, "543s fF, Supp. 235 (M.D. Ala, 1882), aff'd 4.8.7"

103 S.0t., 286 (Nov. 1, 19827},

Therefore, the Court hereby enjoins Etowah County,

Alabama, Lee Wofford, in his official capacity as Probate Judge

of Etowah County, Billy Yates, in his official capacity as

Circuit Clerk of Etowah County and Roy McDowell, in his official

capacity as Sheriff of Etowah County, their agents, servants,

attorneys and those acting in concert with them from failing or

iD

refusing to conduct primary and general elections for the Etowah

County Commission in accordance with the plan submitted by the

parties to this Court.

DONE this MH day of Oc lher

UNIJED STATES DISTRTCT~UPOE