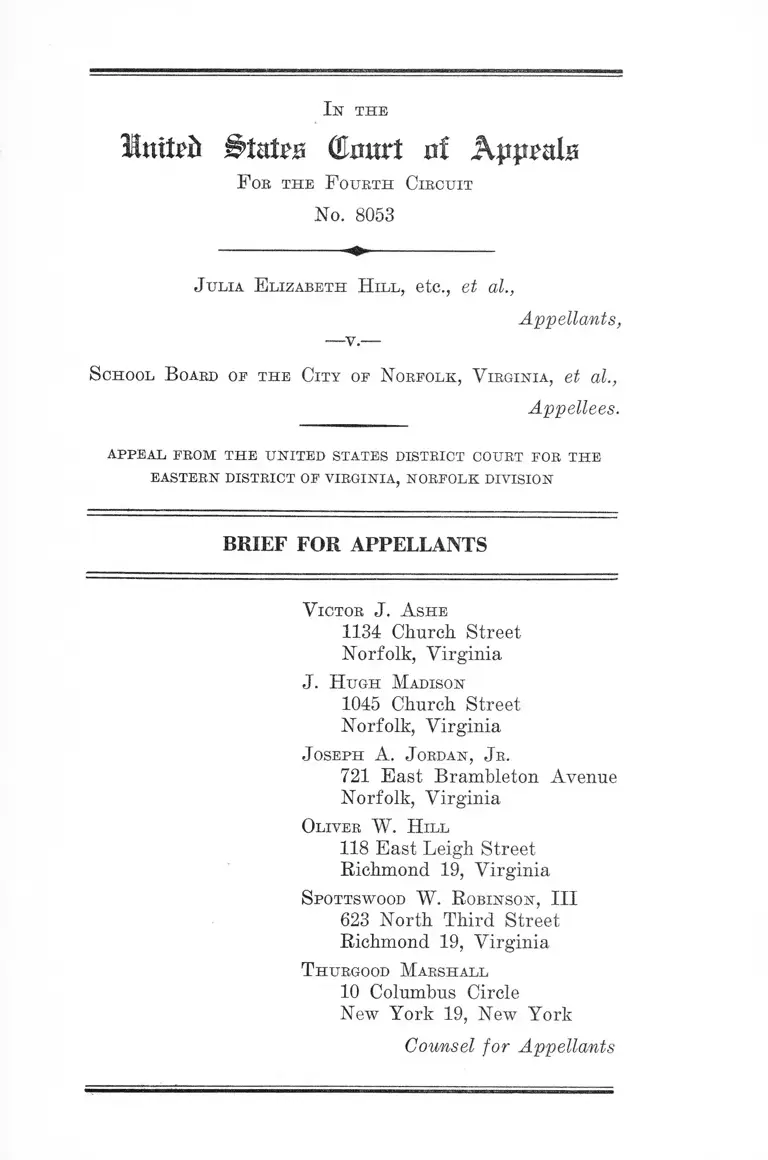

Hill v. City of Norfolk, VA School Board Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hill v. City of Norfolk, VA School Board Brief for Appellants, 1959. 2bd56e36-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9891bca3-6539-4689-b68a-048aba3d80eb/hill-v-city-of-norfolk-va-school-board-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I s r t h e

Imtpft States four! nf Apppalu

F oe t h e F ou rth C ir c u it

No. 8053

J u l ia E l iz a b e t h H il l , etc., et al.,

-v.—

Appellants,

S chool B oard of t h e C it y of N o rfo lk , V ir g in ia , et al.,

Appellees.

a ppe a l from t h e u n it ed states district court for t h e

EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, NORFOLK DIVISION

BR IEF FO R APPELLANTS

V ictor J. A sh e

1134 Church Street

Norfolk, Virginia

J. H u gh M adison

1045 Church Street

Norfolk, Virginia

J oseph A. J ordan, J r .

721 East Brambleton Avenue

Norfolk, Virginia

O liver W . H il l

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

S pottswood W. R obin son , III

623 North Third Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

T hurgood M ar sh all

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Counsel for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case..................... -.......... .......... -....... 1

Questions Presented on Appeal ...................... ............. 3

Statement of Facts ................................-...................... 5

A rg u m en t

I. As applied to appellants denied transfers to desig

nated “all-white” or “predominantly all-white”

schools for failure to qualify therefor under the

academic achievement criterion, appellees’ plan

off ends the equal protection and due process guar

antees of the Fourteenth Amendment in that ap

pellants were subjected to terms and conditions not

similarly applied to white pupils admitted to and

enrolled in such schools............................ .......-...... 10

A. Uncontroverted evidence with respect to appel

lees’ application of the “academic achievement”

criterion conclusively demonstrates that it was

impermissibly discriminatory .......................... 10

B. The difference between the treatment accorded

appellants and others similarly situated is

based upon considerations which invoke the

condemnation of the due process and equal pro

tection guarantees of the Fourteenth Amend

ment ...................................................-................ 13

II. As applied to appellants denied transfers to desig

nated “all-white” schools for failure to qualify

therefor under the geographical criterion, appel

lees’ plan contravenes the due process and equal

11

protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment in

that appellants were subjected to factors and con

siderations not similarly applied to white pupils

resident in the area districted to such schools or

already attending them ......................................... 16

The uncontroverted evidence with respect to

appellees’ application of the “geographic boun

daries” or “residence” criterion conclusively

demonstrates a pattern of different treatment

PAGE

was accorded appellants .................................. 16

C o n clu sio n ............................................................................. ....... 19

T a b l e o p C a s e s :

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954) ..................... 14

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954),

349 U. S. 294 (1955) ..................................................13,14

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917).....................14,16

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 (1950) ....................... 16

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ............................ 14

Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 (1944) ......................... 13

Hill v. Texas, 316 II. S. 400 (1942) .............................. 16

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939) ........................ 13,15

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637

(1950) ......................................................................... 13

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 (1927) ..................... 13

Ill

PAGE

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ........................ 15

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 (1948) ...... 13

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 (1942) ................. 13

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U. S. 553 (1931) ................ ........ 13

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 (1940) ............................ 16

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 IT. S. 629 (1950) ..................... 13

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County, Virginia, 159 F. Supp. 567 (E. D. Va. 1957),

affirmed 252 F. 2d 929 (4th Cir. 1958) ..................... 15

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 IT. S. 356 (1886) 13,14

In t h e

TiUmtvb Court of A^pralo

F ob t h e F ourth C ir c u it

No. 8053

J u lia E liza bet h H il l , etc., et al.,

Appellants,

S chool B oard of th e C it y of N orfo lk , V irg in ia , et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statem ent o f the Case

This case is here on appeal for the third time. In the

first phase of the litigation the District Court passed an

order on February 23, 1957, enjoining appellee school au

thorities of the City of Norfolk, Virginia, from refusing

solely on account of race or color to admit, enroll or edu

cate in any school operated by them any child otherwise

qualified. That order was affirmed by this Court, 246 F. 2d

325, and certiorari was denied by the Supreme Court of

the United States, 355 U. S. 855 (1957). In the next phase

of this litigation the District Court entered an order on

September 18, 1958, approving appellees’ action granting

the applications of certain Negro pupils for transfers to

“white” schools and also upholding appellees’ denial of

enrollment to other applicants. The order as the former

was affirmed by this Court, but the cross-appeal presented

2

on behalf of the latter was dismissed as premature since

the District Court’s order indicated that it had reserved

for further consideration questions as to the validity of

the standards, criteria and procedures promulgated and

applied by appellees. 260 F. 2d 18.

Thereafter, the District Court reconsidered the previ

ously rejected applications which this Court remanded to

it and on May 8, 1959, it entered a memorandum opinion

and an order which sustained appellees’ action in denying

these requests for transfers and held that the standards,

criteria and procedures adopted by appellees’ amended

resolution passed on September 5, 1958, were not uncon

stitutional on their face (App. 17-27; R. 157).

The latest phase of the litigation began on August 13,

1959, when appellees, not in response to any order, but

apparently by reason of a conflict not material on this ap

peal, filed two reports relating to action taken by them on

the applications of certain Negro children for admission

into designated “white” public schools for the 1959-60 school

year (R. 160-161, 164-166). The District Court convened

a pre-trial conference on August 14, 1959, and, following

the same, entered an order which, inter alia, allowed ap

propriate pleadings to be filed by August 19, 1959, on

behalf of the children referred to in the above reports of

appellees (R. 167-168). Within the time prescribed by said

order appellants filed a motion to intervene together with

a complaint in intervention and motions for further relief,

claiming that they satisfied all reasonable requirements for

admission in the schools to which they sought transfers

and that the refusal of their applications by appellees were

based upon considerations of race or color in violation of

law and in contravention of appellants’ rights (R. 169, 174,

178, 190). Appellees filed responsive pleadings which con

troverted the claims of appellants (R. 184, 187, 194, 197);

3

and, after extensive hearings held on August 27-28, 1959,

the District Court entered a memorandum opinion (App.

2-13) and an order (App. 14-16) on September 8, 1959,

which ordered the above pleadings filed as of August 27,

1959, and approved appellees’ rejection of appellants’ ap

plications as based upon a valid application of appellees’

standards, criteria and procedures untainted by considera

tions of race or color.1

The instant appeal in this case is from so much of the

said order as approved appellees’ action as to these appel

lants.

Q uestions Presented

The questions presented on this appeal are as follows:

1. May appellee school authorities’ rejection of a Negro

pupil’s application for transfer to a designated “white”

school on the ground that he failed to qualify under their

criterion

4. The assignment shall be made after consideration

of the applicant’s academic achievement and the

academic achievement of pupils already in the

school to which he is applying

be upheld without offending the due process and equal

protection guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment where

white children whose academic achievement is less or no

better than his are admitted to, enrolled in or assigned to

such school?

2. May appellee school authorities’ rejection of a Negro

pupil’s application for transfer to a designated “white”

1 The order also granted transfers to seven infant plaintiffs not appel

lants here.

4

school on the ground that his performance on certain

achievement tests disqualified him under the foregoing cri

terion be sustained without violating the applicant’s rights

to due process and equal protection of the laws under the

Fourteenth Amendment where the school authorities estab

lish and apply to him a standard of performance or norm

not similarly used with white children who are admitted

to, enrolled in or assigned to such school!

3. May appellee school authorities’ rejection of a Negro

pupil’s application for transfer to a designated “white”

school on the ground that he failed to qualify under their

criterion

5. The assignment shall be made with consideration

for the residence of the applicant

be approved without contravening the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

where the school authorities specifically designated schools

as “Negro” and “white”, maintain overlapping boundaries

for contiguous “Negro” and “white” schools, maintain, de

lineate attendance areas for “Negro” schools located within

the attendance area of a white school, and enroll or assign

white children living in the attendance area served by such

“Negro” school to the “white” school regardless of their

residential proximity to the former?

5

Statem ent o f Facts

Appellee school authorities on March 6, 1959, in compli

ance with an order entered by the court below on February

17, 1959 (R. 140), filed a resolution passed on September 5,

1958, amending the “procedures” prescribed and re-adopt

ing the “standards and criteria” formulated by a prior

resolution passed on July 17, 1958, in relation to the as

signment of pupils to public schools (App. 143 et seq.).

This “plan” (App. 23), in sum, requires all children whose

applications for transfers or initial enrollments involve

“unusual circumstances” to submit to achievement tests

and personal interviews and, in addition, provide that they

must qualify under or satisfy ten standards or criteria.

Appellants, some of whom sought transfers to or initial

enrollment in schools theretofore designated as “all-white”

while the others applied for transfers to schools designated

as “predominantly all white” (R. 158-166, at 164), properly

completed the prescribed procedures. On August 13, 1959,

appellee school authorities voluntarily reported to the

court below on the action taken by them on the applica

tions of certain Negro children, including appellants’, for

transfers or initial enrollment in schools designated “all-

white” or “predominantly all-white” (R. 158 et seq. ) ; ap

pellants’ applications were denied (R. 161, 165).

Following a pre-trial conference convened on August 14,

1959, various pleadings were filed by appellants (R. 169,

174, 178, 190) plus appellees’ responses thereto (R. 184,

187, 194, 197); and on August 27-28, 1959, the case was

heard. The pertinent evidence adduced from the stipula

tions of counsel, the exhibits and the testimony of the

Superintendent of Schools (Mr. Brewbaker), the Assistant

Superintendent of Schools for General Administration (Mr.

6

Lamberth) and appellants’ educational expert (Dr. Hender

son) is not in dispute: Each Negro applicant for admission

to a school designated as “all-white” or “predominantly all-

white” creates an unusual circumstance (App. 42, 48-49, 64).

Of the 18 Negro appellants, all of whom were found other

wise qualified, nine were denied the transfers sought be

cause of low academic achievement and the rest because

of geographical boundaries (App. 40; Court Exs. 3-11, 13-

14,16-23).

1. The data employed by appellee school authorities in

connection with the low academic achievement reason for

rejection were the scores made by appellants on a special

test, the California Achievement Test or, at least, some

form of that test different from the form previously ad

ministered to all pupils in the normal system-wide testing

program (App. 46-48). Appellants’ individual scores

thereon were compared with the national norms published

by the authors of the test used and not with the achieve

ment test scores of pupils already in the schools to which

appellants were applying (App. 50, 101).

Appellants otherwise qualified were rejected because

their individual overall or “total” scores fell below the

national norm (Court Exs. 3-11, 13; App. 52, 56, 59); and

some white pupils already in schools to which appellants

sought transfers either scored below the national norm or

the school norm (App. 101, 102, 104-105, 108). The scores

of appellants ranged from 0.4 to 3.8 years below the na

tional norm for the grade level for which application had

been made: James Alfred Tatem, 0.4 years below the

second grade norm (Court Ex. 5); Gladys Lynell Tatem,

0.7 years below the third grade norm (Court Ex. 4);

Marian Scott, 1.1 years below the ninth grade norm (Court

Ex. 8); Eosa Lee Tatem and Calvin Edward Winston, 1.5

years below the sixth grade norm (Court Ex. 3, 6); William

7

Henry Neville, 1.9 years below the ninth grade norm (Court

Ex. 11); Wilhelmina Scott, 2.5 years below the eleventh

grade norm (Court Ex. 10); Julia Elizabeth Hill, 2.6 years

below the ninth grade norm (Court Ex. 7); Dorothy Elaine

Tally, 3.8 years below the twelfth grade norm (Court Ex.

13).

An expert witness called by appellants at a previous

hearing in this case in August 1958, whose testimony in

corporated by reference into this record by stipulation of

counsel with leave to do so granted by the court below

(App. 40-41), testified that the California Achievement

Tests are extremely limited as a means of determining the

proper grade placement of pupils and as a means of pre

dicting the quality of a pupil’s performance at a particular

grade level (App. 125 et seq.); that the national norms pub

lished by the authors of these tests do not represent mini

mum standards of achievement for pupils in particular

grades because fifty percent of all pupils will score above

and fifty percent below the national averages or norms

(App. 125, 126); that appellants’ scores were compared to

norms of the children at the schools which they were seek

ing to enter; that students who score below the national

norm for a particular grade may get along reasonably well

in their grades (App. 126-127); that within any typical

class at any given grade level there would normally be a

variation of scores among the middle sixty percent equiva

lent to two or three years above or belowT the grade norm

(App. 139); that applicants whose scores fall in the middle

and upper thirds of the range could transfer to “all-white”

or “predominantly all-white” schools without academic fail

ures (App. 129); that a fairer standard than the national

norm would be the 30th percentile, i.e., the score of the

pupil who excels or outscores only thirty percent of the

pupils at a particular grade (App. 131, 132-134); and that

the disparity, i.e., that gap between the national norm

8

and test scores, widens with the passage of time and is

larger in the higher grades (App. 142).

2. Eight of the nine appellants rejected on the basis of

geographic boundaries were seeking transfers from Oak-

wood to Norview Elementary School (an “all-white”

school), but they were placed in the all-Negro, new Rose-

mont School (Court Ex. 16-23); the other appellant re

jected for this reason sought initial enrollment in Norview

Elementary, but was placed in Coronado—another recently

completed, all-Negro school (Court Ex. 14). All were other

wise qualified to be educated at Norview Elementary (Court

Ex. 14, 16-23). All save the appellant placed in Coronado

had unsuccessfully challenged appellees’ denial of their re

quests for transfers to Norview prior to the completion of

Rosemont upon the theory of “too frequent transfers”, i.e.,

to grant the requests at that time would make necessary

an “administrative transfer” to Rosemont upon its com

pletion (App. 18-19, 32-33).

The evidence available and pertinent to the instant re

jections on the basis of geographic boundaries is as fol

lows : Up to this time, appellee school authorities maintain

and establish school districts by race (App. 62, 63, 91, 97);

that once children enter this school system and are initially

placed or enrolled by appellees in the area school maintained

exclusively for persons of their race or color, they follow

this “natural stream” until they graduate from high school

unless application is made for an “unusual circumstances”

transfer and until the procedures, criteria and standards

applied to them by appellees are successfully run (App. 88,

89, 91-94, 97-98); that children racially or ethnically in

one “natural stream” but physically or geographically in

another are placed in the former by appellees, notwith

standing geographic boundaries or any other considera

tion for the residence of the child (App. 92, 93, 94, 95, 97,

9

100-101); that children of white families living in the Rose-

mont and Coronado districts are already attending Nor-

view (App. 96, 98) ;2 that these nine appellants live within

the geographic boundaries of Norview, and that school

districts are not perfectedly situated so as to accommodate

people in strictly geographical considerations so that every

child will have the same distance to walk to the school

nearest his residence (App. 98-99).

The variations in mileage between appellants’ residences

and Norview as against their residences and Rosemont,

Coronado and Oakwood were “not deemed pertinent” by

the court below (App. 32) : Phyllis Delores Russell, seven

blocks to Norview and six blocks to Coronado;3 Glenda

Gale Brothers, 1.8 miles to Oakwood and 1.1 miles to

both Norview and Rosemont; Charlene Butts, 0.7 miles

to both Oakwood and Norview and 0.4 miles to Rosemont;

Melvin G. Green, Jr., and Minnie Alice Greene, 1.4 miles

to Oakwood and 0.3 miles to both Norview and Oakwood;

Cloraten Harris and Rosa Mae Harris, 1.3 miles to Oak-

wood and 0.5 miles to Norwood and one block to Rose

mont; Sharon Venita Smith and Edward H. Smith, III,

1.3 miles to Oakwood and 0.7 miles to Norview and 0.6

miles to Rosemont (App. 33).

Whereupon, the court below on September 8, 1959, en

tered the order from which the 18 Negro applicants de

nied the right to attend schools designated “all-white”

or “predominantly all-white” have prosecuted this appeal.

2 See also Tr. Proceedings of August 27-28, 1959, at pp. 263-264, 266-

270, 272-275, 277-278.

3 Id., at 278.

1 0

A R G U M E N T

I.

As applied to appellants den ied transfers to designated

“ all-w hite” or “predom inantly all-w hite” schools for

fa ilu re to qualify th erefor under the academ ic ach ieve

m ent criterion , ap p ellees’ p lan offends the equal p ro

tection and due process guarantees o f the Fourteenth

A m endm ent in that appellants w ere subjected to term s

and cond itions not sim ilarly applied to w hite pup ils

adm itted to and en ro lled in such schools.

The applications of nine of the 18 applicants here were

denied by appellees on the ground that their academic

achievement did not justify the transfers sought; and the

court below approved appellees’ action. These nine ap

pellants respectfully submit that this action was erroneous

and violative of their rights to due process and the equal

protection of the laws.

A. U n co n tro v e rted ev idence w ith re sp e c t to ap p e llees’

ap p lica tio n o f th e “ academ ic ach iev em en t” c r ite r io n

conclusively d em o n stra te s th a t it was im p erm issib ly

d isc rim in a to ry .

On September 5, 1958, appellee school authorities passed

a resolution amending and adopting a prior resolution

in relation to “all applications for transfers and initial

assignments which involve “unusual circumstances” and

prescribing assignment standards, criteria and procedures”

for processing and considering such applications (App.

143 et seq.). For the present it suffices to point out that

this “plan” requires every Negro child applying for trans

fers to or enrollment in designated “all-white” or “pre

dominantly all-white” schools to submit to special tests,

the score on which is supposed to furnish appellees one

11

factor in the equation necessary for their determination

and “consideration of the applicant’s academic achieve

ment and the academic achievement of pupils already in

the school to which he is applying” (App. 150).

The pattern of “different” treatment meted appellants

by appellees under this aspect of the plan is glaring. For

the record contains unqualified admissions that each ap

pellant’s individual score was “considered” in relation to

the national norms published by the authors of the given

tests rather than in relation to “the academic achievement

of pupils already in the school to which he [was] apply

ing” (App. 50, 101).

The record is replete with additional evidence that ap

pellees applied the “academic achievement” criterion to

appellants under conditions not similarly applied to other

pupils admitted to or enrolled in the schools appellants

sought to enter. First, transfers were refused appellants

because their overall or “total” scores fell below the na

tional norm on “special” tests given only to them (Court

Ex. 3-11; App. 52, 56, 59) whereas there is uneontradicted

evidence that not all children in “all-white” or “predom

inantly all-white” schools achieve test scores above the

national norm. Indeed, it was readily conceded that in

Norfolk, as elsewhere, some white pupils already in such

schools scored below the national norm and others even

scored below the school norm (App. 101, 102, 104-105, 108).

It also appears without contradiction that many of the

rejected Negro children achieved scores on the “special

test” either higher or, at least, no lower than those achieved

on “normal tests” by white children in the grades the

Negro children sought to enter (Ibid.).

It also appears from the evidence that where a white

child is already enrolled in a particular school, or is

seeking admission to that school, he is normally enrolled

12

in or assigned to the grade in that school for which he is

determined to be qualified to enter notwithstanding his

academic achievement score (App. 54, 57-59). On the other

hand, Negro children in the category under consideration,

although considered qualified to enter Negro schools at

the grade level to which he was last promoted, would be

denied admission to any grade in the designated “all-

white” or “predominantly all-white” school to which trans

fers were sought.

Finally, in view of the unchallenged testimony of ap

pellants’ expert witness as to the limited value of the

special achievement tests taken by appellants and that

many pupils who score below the national norm for a

particular grade level often get along reasonably well at

such grade level (App. 125 et seq.), a disqualifying stand

ard not applied to pupils already admitted to or enrolled

in “all-white” or “predominantly all-white” schools has

been imposed on appellants. This appears when one con

siders that most of the rejected applicants scored less

than two years below* grade level and only one scored

over three years wdiereas, almost as documentation for

the expert testimony, some children already attending

schools to which these appellants sought admission were

at least two years below grade level (App. 54, 58, 101,

104).

13

B. T h e d ifference betw een th e tre a tm e n t acco rded

a p p e lla n ts an d o th e rs sim ila rly s itu a ted is b ased

u p o n c o n sid e ra tio n s w hich in v o k e th e co n d em

n a tio n o f th e d u e p rocess an d eq u a l p ro te c tio n

g u a ran tee s of th e F o u r te e n th A m endm en t.

These appellants do not assert a constitutional right to

enter a grade for which they are scholastically unqualified.

Rather, they desire to be admitted to the schools to which

they applied and assigned to the grades in those schools to

which their academic qualifications, if they were white,

would normally justify their admission. In short, their

claim is that, in the way of school assignment and grade

placement, they should have been treated just as similarly

situated white children are normally treated.

The equal protection of the laws is “a pledge of the pro

tection of equal laws.” Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356,

369 (1886). It does not leave the state free to unjustifiably

impose upon the exercise of rights by one group require

ments not applicable to other groups. Smith v. Cahoon,

283 U. S. 553 (1931). See Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268

(1939). Classifications violate the Constitution when they

unjustifiably increase the group burdens, or depreciate the

group benefits, of public education. Sweatt v. Painter, 339

U. S. 629 (1950); McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents,

339 U. S. 637 (1950); Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S.

631 (1948). And it is hardly necessary to state that the

difference in treatment cannot be justified upon grounds of

race. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954);

Sweatt v. Painter, supra; Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283

(1944); Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 IT. S. 535 (1942), at 541;

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 541 (1927). Where, as

here, such requirements are enforced at all, they must be

enforced without unequal results among groups identically

situated despite difference as to race. Here the “special”

14

requirements contained in the “plan” under consideration

had been imposed only upon Negro children seeking to

enter “all-white” or ‘predominantly all-white” schools and

might be imposed upon white children seeking entry to

“Negro” schools. The single factor determinative of its

operation in particular cases is the difference in race be

tween the appellants and those already in the school. Sub

jection to the “plan” thus depends solely on race—“simply

that and nothing more.” Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S.

60, 73 (1917).

Neither the making of classifications based upon race

nor different treatment (by imposition of burdens or grant

of benefits) to groups defined by racial considerations have

any reasonable relation to any legitimate purpose of the

appellee School Board. Such discriminations by the school

board constitute deprivations of liberty without the due

process of law and denials of the equal protection of the

laws in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954); Bolling v.

Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954); Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S.

1 (1958).

An unjust discrimination not expressly made by the “cri

teria” adopted by appellees, but made possible by them,

is nevertheless a denial of equal protection. Tick Wo v.

Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) is the classic statement of

the rights of persons aggrieved by discriminatory adminis

tration of schemes appearing innocent on the surface,

where, at pp. 373-374, the Court said:

. . . Though the law itself be fair on its face and im

partial in appearance, yet, if it is applied and admin

istered by public authority with an evil eye and an

unequal hand, so as practically to make unjust and

illegal discriminations between persons in similar cir

15

cumstances, material to their rights, the denial of equal

justice is still within the prohibition of the Constitu

tion.

The fact that this different treatment may apply to white

children who seek enrollment in “Negro” schools, as well

as to Negro applicants to “white” schools, is entirely beside

the point. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 21-22 (1948).

In any event, in all of its ramifications the “plan” here in

volved had been applied only to Negroes.

The fact that the “plan” may not absolutely preclude all

Negro children, and that exceptionally gifted children may

survive its operation, does not save it from constitutional

condemnation. Indisputably, it discriminates against the

class that included the Negro appellants here by imposing

greater demands upon them than upon others. This vice

in its operation alone suffices to render it invalid. As the

Court in Lane v. Wilson, supra, at 275, stated in treating

another constitutional right:

The [Fifteenth Amendment] nullifies sophisticated

as well as simple-minded modes of discrimination. It

hits onerous procedural requirements which effectively

handicap exercise of the franchise by the colored race

although the abstract right to vote may remain un

restricted as to race.

Nor is its approval to be affected by the consideration

that the discrimination resulting from the .operation of the

plan may not have been intended by the appellees. “It is

immaterial that the defendants may not have intended to

deny admission on account of race or color. The inquiry is

purely objective. The result, not the intendment, of their

acts is determinative.” Thompson v. County School Board

of Arlington County, 159 F. Supp. 567, 569 (E. D. Va. 1957),

16

aff’d 252 F. 2d 929 (4th Cir. 1958). Non-intentional dis

crimination is nonetheless unconstitutional. Cassell v.

Texas, 339 U. S. 282 (1950); Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400

(1942); Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 (1940). The fact that

appellee School Board sought to achieve, by the means em

ployed, compliance with the previous orders of the court

below is equally impotent. However well intended their

efforts may be, this objective cannot be attained by a de

vice that denies rights created or protected by the Federal

Constitution. Buchanan v. Warley, supra, at 81.

II.

As applied to appellants denied transfers to designated

“ all-w hite” schools fo r fa ilu re to qualify th erefor under

the geographical criterion , ap p ellees’ p lan contravenes

the due process and equal protection clauses o f the

F ourteenth A m endm ent in that appellants w ere sub

jected to factors and considerations not sim ilarly ap

p lied to w hite pup ils resident in the area districted to

such schools or already attending them .

The applications of the remaining nine appellants were

for transfer to a designated “all-white” school. Appellees

denied them on the ground that their places of residence

were not only located within the areas zoned for the all-

Negro schools in which they were placed but were physically

nearer; and the court below again approved appellees’ ac

tion. These appellants also respectfully submit that that

action was erroneous and an infringement of the due

process and equal protection provision of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

The uncontroverted evidence with respect to appellees’

application of the “geographic boundaries” or “resi-

17

dence” criterion conclusively demonstrates a pattern

o f different treatment was accorded appellants.

The nine appellants in this category reside in what is

known as the Norview Annex, or section, of Norfolk. Prior

to September, 1959, two elementary schools served this

area, the Norview and Oakwood Elementary Schools. The

former was attended only by white children and the latter

by Negro children. Since the above mentioned date, two

more all-Negro schools have been opened. Appellants first

made application for transfer to or enrollment in Norview

in 1958 while the construction of the new all-Negro elemen

tary schools, Rosemont and Coronado, was pending. All

save one of the present appellants previously prosecuted an

unsuccessful challenge to appellees’ denial of their requests

upon the theory of “too frequent transfers”, i.e., allowance

of such requests at that time would only create a neces

sity for an additional transfer upon the completion of the

new schools (App. 18-19, 32-33).

Those appellants, joined by another Negro child seek

ing initial enrollment in Norview, but now placed in Coro

nado, again sought transfers to Norview. And on this oc

casion they were rejected on the ground that their resi

dences were in the school area served by Rosemont or Coro

nado and these schools were physically closer or more

accessible to their homes (see App. 12-13, 33).

In addition to the evidence previously set forth as avail

able on the record herein and pertinent to these rejections,

see Statement of Facts, supra, at pp. 8-9, the vice under

girding the application of the geographic factor in appel

lees’ plan to these appellants is the fact that appellees

have accentuated and enforced their continuing policy of

maintaining and establishing school districts separated and

denominated in terms of race by playing fast and loose with

18

appellants’ constitutional rights to nonsegregated educa

tion during the period when the Eosemont and Coronado

schools were under construction.

Another salient fact which illustrates and emphasizes

the distinction made by appellees in the application of the

geographic factor to appellants and others is that a white

pupil residing in the same block as appellants would be

assigned notwithstanding the applicable geographic fac

tors and school areas to schools to which appellants sought

and were denied transfers. Finally, indisputable eviden

tiary facts are bared when one recalls that each of the

boundaries or areas served by the three all-Negro schools

is located within the Norview boundaries or zone.

From the foregoing facts, it is submitted that appellees’

application of the “geographic” or “residence” criterion to

appellants has subjected them to restrictions or burdens

not imposed upon all other persons of like age and academic

achievement who reside in the Norview Annex.

19

CONCLUSION

For the reasons h ere in b efore stated, appellants re

sp ectfu lly subm it that the action o f the D istrict Court

should be affirm ed as to the m atters involved in the orig i

nal appeal, and reversed as to the m atters involved in

th e cross-appeal.

Respectfully submitted,

V ictob J . A sh e

1134 Church Street

Norfolk, Virginia

J . H u gh M adison

1045 Church Street

Norfolk, Virginia

J oseph A. J ordan, J r .

721 East Brambleton Avenue

Norfolk, Virginia

Oliver W . H il l

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

S pottswood W. R obin son , III

623 North Third Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

T hurgood M arsh all

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Counsel for Appellants

sa