Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education Brief for Petitioners, 1969. 6f87dd85-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/98aad1d4-3f91-4aaf-8d30-dda63c452f6f/alexander-v-holmes-county-board-of-education-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

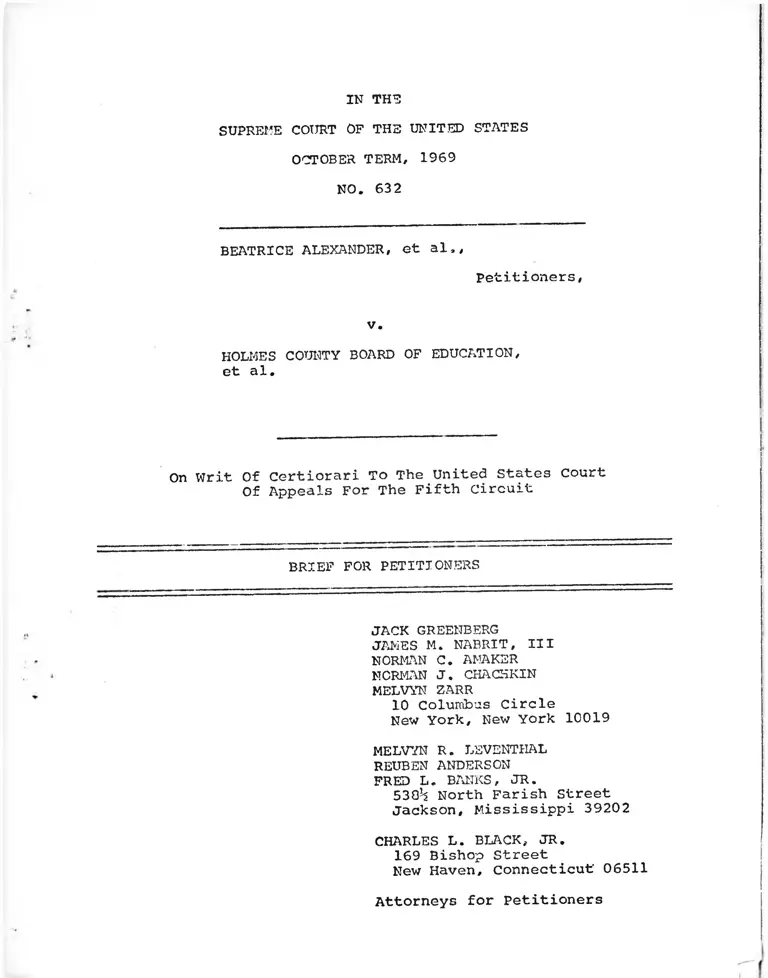

in t h e

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

NO. 632

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et al,,

Petitioners,

v.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court

Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN C. AMAKER

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

MELVYN ZARR10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

REUBEN ANDERSON

FRED L. BANKS, JR.530^ North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

CHARLES L. BLACK, JR.

169 Bishop StreetNew Haven, Connecticut" 06511

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Page

1

Opinions Below ................

jurisdiction ....................

Constitutional Provision Involved • • * ........

Questions Presented • • • • * * * * ------

Statement ......................

Summary of Argument ..............

Argument

I.

II,

The Time for Delay of School Desegregation

Has Run Out......................

Effective Relief Requires the Immediate

Suhmitte^Office^of*1 Education^ Plans______

Pendente Lite................

Conclusion

1

2

2

3

18

19

26

34

Table of Cases: .

Adan,s v. Mathews. 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968) . . .

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . 4.

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (195S)

Coffey v. State Educational ^ ^ 9" ^ ' ------ 8

296 F. Supp. 13«y ko.u.

Dowell v. Board of Education °f Oklahoma exty^

Schools 344 F. Supp. °1967), cert.

affirmed 375 F«2d^ y . ^ .............. 32denied, 387 U.S. 931 (1967) . •s srs.’sss...... *

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ........

Page

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School • ..

District, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969) * • • • • *

in re R. Jess Brown, 346 F.2d 903 (5th Cir. 1965) . . 20

Leake County School Board v. Hudson, 357 F.2d 653

(5th Cir. 1966) ................................

McLaurin v. Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950)............ ^

Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968) . . . 20

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965).......... 5,11

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966).......... 3

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950).............. 19

United States v. Barnett, 330 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1963) 4

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969) ........

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

District, 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cxr. 1969) ..........

U. S. and Danita Hampton v. Choctaw County Boardof Education, 5th Cir. No. 27297, June 26, 196

Statutes; : 1 • -•

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ................ .. 1

28 U.S.C. § 1343(3)! ........

342 U.S.C. § 1981.............................. * ‘ ‘

----- ' r 342 U.S.C. § 1983 ....................................

Other Authority;

United States Commission on Civil Rights FederalEnforcement of School Desegregation (September

11, 1969) ............................ .. * * 11.13,20

• •- ii -

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

NO. 632

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et al..

Petitioners,

v.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court

Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The order of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit under review is unreported and is set forth in

Appendix E to the Petition. Earlier opinions of the Court of

Appeals and of the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Mississippi are unreported and are set forth in

Appendices A through D to the Petition.

jurisdiction

jurisdiction of this Court is based upon 28 U.S.C. §1254(1)

to review the Court of Appeals' order delaying the implementation

of school desegregation plans in 14 school districts in

Mississippi.

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit was entered August 28, 1969 (Appendix E to

the Petition, p. 71a). Petitioners' petition for writ of

certiorari was filed September 23, 1969 and granted October

9, 1969.

Constitutional Provision involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of Section

1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

Questions Presented

1. Should this Court permit any further delay, for

whatever reason, in implementing plans to convert dual school

systems into unitary systems?

2. Should this Court require as a condition of effective

relief that educationally sound plans developed by the United

States Office of Education be implemented immediately pendente

lite?

2

Statement

These cases test how much longer Negro schoolchildren

in 14 substantially segregated school districts in Mississippi

must wait to realize their right to an education in a unitary

1/ These cases were filed in the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Mississippi between the years

1963 and 1967. Jurisdiction was predicated upon 28 U.S.C.

§1343(3) and 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1983 and the Due Process and

Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. Plain

tiffs in school desegregation cases in Mississippi often sue

several school boards located within the same geographical area

under one civil action number; the nine cases brought here by

this petition involve fourteen separate school districts.

First, there are three cases wherein suit was brought by

Negro schoolchildren against six separate school districts:

Harris v. Yazoo Counts Board of Education, Yazoo City Board

of Education and Holly Bluff Line consolidated School District?

Alexander v. Holmes Countv Board of Education; Kiilingswortn

v# The Enterprise consolidated School District and Quitman

Consolidated School District.

Second, there are four cases wherein suit was brought by

Negro schoolchildren against six school districts and the Unite:.

States subsequently intervened: Hudson and United _ States v.

Leake County School Board; Blackwell and United States v.

Isseguena County Board of Education and Anguilla Line__gcns_g_li

dated School District; Anderson and United States v. Canton

Municipal Separate School District and Madison county School.

District-; Barnhardt and United States v. Meridian separate

School District.

Third, there are two cases which were filed by the United

States wherein Negro schoolchildren subsequently intervened:

United States and George Williams v. Wilkinson County Board

of Education; United States and George Magee, Jr. v. North

Pike Countv Consolidated School District.

This petition formally embraces only school desegregation

suits involving private plaintiffs. But the disposition of

this petition will govern an additional 16 suits involving 19

school districts against whom the United States is the sole

plaintiff in companion cases below.

3

school system decreed by this Court more than 15 years ago in

2/

Brown v. Board of Education.

For 10 years after Brown v. Board of Education, the public

schools of Mississippi remained totally segregated. Although

Mississippi state officials had initially experimented with

open defiance to defeat this Court's ruling, see United States,

v. Barnett, 330 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1963), they soon turned to

less obvious — and sometimes ingenious — devices for delay.

A pupil placement law was passed, which established a

labyrinth of administrative procedures to ensnare those Negro

students hardy enough to attempt to desegregate white schools.

For a season that worked. The first public school desegregation

suits brought in federal court in Mississippi were dismissed

for failure to exhaust administrative remedies under the Pupil

Placement Law. So it was that while this Court, in 1964, was

holding that "the time for mere 'deliberate speed' has run

out" (Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218, 234 (1964)), not a

single child in Mississippi attended an integrated school.

That year, the Court of Appeals reversed the district

court's dismissal of the first school desegregation suits.

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 328 F.2d

408 (5th Cir. 1964). Upon remand, the school boards and white

intervenors delayed the trials with voluminous testimony as

to the innate inferiority of Negroes as a rational basis for

continued segregation. The district court, after further delay,

entered findings of fact supporting the defendants' theories

2/ 347 U.S. 483 (1954)(Brown I); 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown

II) •

4

of racial superiority, but held that it was compelled by the

Court of Appeals to require a grade-a-year plan — thus seeking

to insure that the time for "deliberate speed" would run until

1976. That decision was overturned in Singleton v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir.

1965)(injunction pending appeal); 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966).

The school boards involved in this litigation next turned

to "freedom of choice" plans to delay real desegregation. Then

came this Court's decision in Green v. County School Eoard of

New Kent County. 391 U.S. 430 (1968). The petitioners moved

the district court to require each respondent school board to

adopt a new desegregation plan which "promises realistically

to work, and promises realistically to work now" (Green, supra,

391 U.S. at 439 (1968)(Emphasis Court's)). Petitioners were

prepared to show that these freedom of choice plans did not

work to disestablish the dual school systems-. Indeed,

petitioners were prepared to show that the token results

achieved by these plans were even less than the results held

5

3/ But the district court refused toinsufficient in Green,

schedule an early hearing on petitioners' motions, thus allowing

the 19G8-69 school year to start under these defective freedom

Of choice plans.

3/ The extent of student desegregation in the school districts

at bar is shown in the following table:

District Percentage of Negroes Percentage of Negroes

in All-Negro Schools in Predominantly

White Schools

1968-69* 1969-70** 1968-69* 1969-70**

(Projected) (Projected)

Anguilla 94.4% 96.1% 5.6% 3.9%

Canton 99.5% 99.9% 0.5% 0.1%

Enterprise 84% 16%

Holly Bluff 98.9% 1.1%

Holmes County 95.5% 4.5%

Leake County 97.1% 95.7% 2.9% 4.3%

Madison County 99.1% 99.1% 0.9% 0.9%

Meridian 91.4% 84.8% 8.6% 15.2%

North Pike County 99.2% 99.7% 0.8% 0.3%

Quitman 96.1% 3.9%

Sharkey-Issaquena 94.6% 93.6% 5.4% 6.4%

Wilkinson County 981% 97.3% 1.9% 2.7%

Yazoo 91.2% 8.8%

Yazoo County 93.3% 6.7%

* These figures are based upon the school districts’ reports

to the district court.

** The projections are based for the most part upon the freedom

of choice forms completed during the Spring of 1969, as

compiled by the United States and submitted to the Court of

Appeals.

6

Accordingly, petitioners moved the Court of Appeals for

summary reversal of the district court's refusal to grant

expeditious relief for the 1968-69 school year. On August 20,

1968, the Court of Appeals ordered the district court to

conduct hearings no later than November 4, 1968 and to provide

relief effective with the 1968-69 school year. Adams v.

Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968).

Upon remand, the district court consolidated these school

desegregation cases brought by the Negro plaintiffs with those

brought by the United States and conducted hearings, en banc,

4 /

starting in October, 1968. At these hearings, the respond

ent school boards presented extended testimony to the effect

that achievement test results justified the continued use of

free choice assignments and concomitant token integration of5/

white schools and perpetuation of all-Negro schools. Indeed,

4/ The consolidated cases proceeded under the caption United

States v. Hinas County Board of Education and Alexander v.

Holmes Countv Board cf Education. They embraced 19 districts

against whom the United States was the sole plaintiff, plus

the 14 districts at bar. See note 1, supra.

5/ This position was urged by Mississippi school districts

and white parent intervenors in 1964 to retain totally segre

gated schools. Lengthy expert testimony was presented and the

district court entered findings of fact supporting the pro-^

position that Negroes were innately inferior; but the district

court felt bound by Court of Appeals' rulings to deny defend

ants' request that Brown v. Board of Education be overruled.

The defendants appealed and the Court of Appeals ordered an

end to such efforts to justify segregation. Jackson Municipal.

Separate School Districts v. Evers; Biloxi Municipal Separate

School District v. Mason; and Leake County School Board v.

Hudson, 357 F.2d 653 (5th Cir. 1966). The last case cited,

Hudson, is the same case before the Court in this petition.

7

the cases were consolidated primarily to permit the school

boards to join in this "expert" testimony. The respondent

school boards also resisted any alteration of the free choice

plans on the ground that more than token integration would

be followed by withdrawal of white children from the public6/

schools and the proliferation of private schools.

The hearings dragged on into December, well past the

Court of Appeals' hearing deadline of November 4, 1968.

Thereafter, the district court waited until May 13, 1969 to

rule, notwithstanding the Court of Appeals had directed it

to treat the cases "as entitled to the highest priority"

and to provide relief effective with the 1968-69 school

year (403 F.2d at 188) . It approved freedom of choice plans

7/

for all the respondent school districts.

6/ Mississippi's first effort to retain segregated schools

through tuition grant legislation was held unconstitutional

on the ground that the legislation's purpose and effect was

to perpetuate segregation. Coffey v. State Educational

Commission, 296 F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. Miss., 1969)(3-judge court)-

The Mississippi legislature recently enacted a new tuition

grant program, in the nature of student loans, to enable white

students to attend private schools (House Bill No. 67). Also

passed by the House of Representatives (under consideration by

the Senate) is a bill which would grant up to $500 in credits

toward Mississippi income taxes for all payments or donations

to schools, "public or private."

2/ The opinion and orders of the district court are set forth

in Appendix A to the Petition. The order in Alexander v.

Holmes County Board of Education is set forth at p. 20a and is

representative of the orders entered in eight of these nine

cases. The ninth order, entered in Killingsworth v. Enterprise

Consolidated School District is set forth at p. 21a. It

differed from the others in that it dismissed the petitioners'

motion on the ground, later held erroneous by the Court of

Appeals, that the petitioners had not explicitly authorized

their attorney to file the motion.

8

Promptly thereafter, in June, 1969, the petitioners

and the United States moved the Court of Appeals for summary8/

reversal or expedited consideration of the cases. On June

25, 1969, the Court of Appeals entered a 3.etter directive

expediting consideration of the cases, see Appendix B to

Petition, pp. 24a-27a.

On July 3, 1969, the court of Appeals held that the

freedom of choice plans were not working to disestablish

the dual school systems at bar and directed the district

court to require from the school boards plans of desegrega

tion other than freedom of choice, Appendix B to the Petition,

pp. 28a-37a. The Court found:

(a) that not a single white child attended

a Negro school in any of the districts;

(b) that the percentage of Negro children

attending white schools ranged from

zero to 16 per cent;9/

(c) that token faculty integration continued

in force; and,

(d) that school activities continued sub

stantially segregated.

Quoting Adams v. Mathews, supra, the Court held that "as a

matter of law, the existing plan fails to meet constitu

tional standards as established in Green" (Appendix B to

8/ petitioners moved for summary reversal on June 10, 1969;

the United States moved for summary reversal or, in the

alternative, for expedited consideration on June 23, 1969.

9/ in the districts at bar, the percentages ranged from

0.1% to 8.8%, with the lone exception of Meridian, which had

a projected percentage of 15.2%. See note 3, supra.

9

Petition, p. 32a). The Court of Appeals directed that the

respondent school boards be required to collaborate with the

United States Office of Education in formulating new desegre

gation plans effective for the 1969-70 school year (Appendix

B to Petition, pp. 35a-36a). A precise timetable for the

submission and implementation of the plans was established

to protect petitioners' right to relief effective for the

1969-70 school year (Appendix B to Petition, pp. 36a~37a).

The Court directed that the mandate^be issued forthwith

(Appendix B to Petition, p. 37a).

The collaboration with the Office of Education was

required because the court "deem[ed] it appropriate for the

Court to require these school boards to enlist the assistance

of experts in education as well as desegregation? and to

require the school boards to cooperate with them in the

disestablishment of their dual school system" (Appendix B

to Petition, p. 32a).

Collaboration with the Office of Education was especially

appropriate because the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, pursuant to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, fixed minimum administrative standards to be applied

in determining the qualifications of schools applying for

federal financial aid. This administrative enforcement by

HEW had, since 1964, produced a dramatic increase in the level

of desegregation in the South. See United States Commission

10/ The respondent school boards filed a petition for

rehearing en banc, which was denied on October 9, 1969.

10

on civil Rights, Federal Enforcement of School Desegregation,

p. 31 (September 11, 1959). The courts accorded "great

weight" to those minimum standards and established "a close

correlation , , . between the judicial's standards in

enforcing the national policy requiring desegregation of

public schools and the executive department's standards in

administering this policy" (Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729, 731 (5th Cir. 1965).

This united action of the courts and the executive in

advancing toward their common objective of school desegrega

tion made it possible for the Court of Appeals to set the

constitutional deadline for compliance at the 1969-70 school

year. See Adams v. Mathews, supra; United States v. Greenwood

Municipal Separate School District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir.

1969); Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School District,

409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969); United States v. Indianola

Municipal Separate School District, 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir.

1969).

Accordingly, in its modified order of July 25, 1969, the

Court of Appeals made clear that September 1, 1969 was to be

the final date of implementation of plans "to immediately

disestablish the dual school system[s] in question" (Appendix

B to Petition, p. 39a).

On August 11, 1969, the deadline established for sub

mission of the new desegregation plans, the Office of Education

submitted plans of desegregation for the 33 school districts

11

t

to the district court.'W Thirty of the 33 plans provided

for implementation of pairing and/or zoning plans of desegre

gation to be effective with the commencement of the 1969-70

school year.-7 In his transmittal letter of August 11 (See

Appendix C to Petition, pp. 40a-42a), Dr. Anrig. the (then)

Director of the Equal Educational Opportunities Division of

the Office of Education — the educational expert responsible

for the final review of the plans - stated to the district

H i o n Y o ^£ * ! £ > “ Theseplans fall loughly into 3 categorxes.

First some boards proposed the implementation of a

"tracking" system, ^ ef ^ J ^ ud^ 3?gned1?ob? n r o f t ^ schools

students. The beards proposed t 1969-70 school yearto implement the plans, so that during the 1969 ™ school ye

only grades 1-4 would be "desegregated1 through achievement

testing, while freedom of choice remained m ef.ect *n th

grades not yet reached.

Second, some boards proposed geographic zoning or pairing

plans, with achievement test results being used for stude

assignments within each school. Thus, . , one forgrades in each school: one for bright students and one for

the others. _ __

Third, some boards proposed plans provided for continued

of freedom of choice, but assuring that a substantial

-percentage of the enrollment of formerly all-white schools

would be Neqro through administrative assignments. These

p?ais did n o r Providl for the assignment of whites to Negro

schools.

!•>/ The exceptions were for Hinds County, Holmes County and

Meridian in which it was asserted that problems peculiar t

those districts required postponing full implementation until

the beginning of the 1970-71 school year.

12

court (Appendix C to Petition, p. 44a) :

I believe that each of the enclosed plans

is educationally and administratively sound,

both in terms of substance and in terms of

timing. In the cases of Hinds County,

Holmes County and Meridian, the plans that

we recommend provide for full implementation

with the beginning of the 1970-71 school year.

The principal reasons for this delay are con

struction, and the numbers of pupils and

schools involved. In all other cases, the

plans that we have prepared and that we

recommend to the court provide for complete

disestablishment of the dual school system

at the beginning of the 1969-70 school year.

But on August 19, 1969, there occurred 11 a major retreat

in the struggle to achieve meaningful school desegregation

(Statement of the United States Commission on Civil Rights,

p. 2, September 11, 1969).

On that day, the Secretary of the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare sent a letter to the Chief Judge of

the Court of Appeals and the judges of the district court

requesting that the plans submitted by the Office of Education

be withdrawn and that the 1969—70 deadline for implementation

of plans be rescinded (Appendix C to Petition, p. 54a)• The

Secretary did not dispute Dr. Anrig's view that the plans

were "educationally and administratively sound." Instead,

the Secretary noted that he had reviewed these plans "as the

Cabinet officer of our Government charged with the ultimate

responsibility for the education of the people of our Nation"

(Appendix C to Petition, p. 52a). He continued (Appendix C

13

to Petition, p. 54a) :

In this came capacity, and bearing in mind

the great trust reposed in me, together with

the ultimate responsibility for the education

of the people of our Nation, I am gravely con

cerned that the time allowed for the develop

ment of these terminal plans has been much too

short for the educators of the Office of

Education to develop terminal plans which can

be implemented this year. The administrative

and logistical difficulties which must be

encountered and met in the terribly short

space of time remaining must surely in my

judgment produce chaos, confusion, and a

catastrophic educational setback to the 135,700

children, black and white alike, who must look

to the 222 schools of these 33 Mississippi dis

tricts for their only available educational

opportunity.

The Secretary requested that the Office of Education and

the respondent school boards be given until December 1, 1969

to formulate new plans for desegregation, with implementation

of those plans to be left to an unspecified future time

(Appendix C to Petition, p. 52a).

The next day, August 20, 1969, the Court of Appeals

entered an order acknowledging receipt of the Secretary's

letter (Appendix C to Petition, p. 55a). August 21, 1969,

the Department of Justice filed a motion in the Court of

Appeals requesting modification of the Court's order of

July 3, 1969, based upon the Secretary's letter, and

petitioners filed their opposition thereto. The next day,

the Court of Appeals orally granted leave to the district

court "to receive, consider and hear the Government's motion

for extension time until December 1, 1969" (see order of

the Court of Appeals of August 28, 1969, Appendix E to Petition,

14

13/p. 75a). On August 25, 1969, the district court held a

hearing on the Government's request.

At the hearing, the Government presented testimony of

two of Dr. Anrig's subordinates at the Office of Education.

They testified "that the HEW plans in question are basically

sound" (Opinion of the district court of August 26, 1969,

Appendix D to petition, p. 64a; Tr. 96, 142, 173, 180-82).

Moreover, they testified that these would likely be the plans

submitted if the submission date was delayed until December 1,

1969 (Tr. 113-14, 122, 142) .

The delay was to be used for "the in depth peripheral

studies such as curricular studies and financial studies

required to implement these new plans" (Opinion of the dis

trict court of August 26, 1969, Appendix D to Petition, pp.

64a-65a). Moreover, the delay "would allow collaboration

between the Office of Education and the defendant school

districts to prepare for implementation of the terminal plans,

thus resulting in better education and better community

relations and consequently, an effective, workable desegrega

tion of the defendant school districts and the conversion from

a dual to a unitary system" (Appendix D to Petition, p. 65a).

Although the letter of the Secretary of the Department

of Health, Education and Welfare had referred to "adminis

trative and logistical difficulties" requiring delay (Appendix

C to Petition, p. 54a), no particular difficulty with respect

13/ Circuit Judge Gevin indicated his disagreement with this

procedure and voted to grant the respondent school boards'

petition for rehearing en banc in order to review it.

15

to any particular school system was presented to, or found by,

the district court. Instead, the district court found only

the generalized and long anticipated need to redraw bus routes,

reassign teachers, convert classrooms, adjust curricula and

engage in "faculty and student preparation, including various

meetings and discussions and the solutions therefor" (Opinion

of the district court of August 26, 1S69, Appendix D to

14/

Petition, p. 65a).

The Government recommended to the district court, in

addition to the delayed submission date of December 1, 1969,

that each school district, in conjunction with the Office of

Education, develop a program for this preparatory work and

report to the Court no later than October 1, 1969.

The next day, August 26, 1969, the district court entered

its findings of fact and conclusions of law, recommending that

the Government's motion be granted (see Appendix D to Petition,

pp. 56a-70a).

Two days later, on August 28, 1969, the Court of Appeals

granted the Government's request for delay (Appendix E to

Petition, pp. 71a-78a). Specifically, the court of Appeals

withdrew the firm implementation date of September 1, 196915/

"to immediately disestablish the dual school system[s]" and

substituted in its place the date of December 1, 1969, for

14/ The petitioners' education expert testified that this

type of in-service training program "is often much more helpful

to people who are actually grappling with any problems, if there

are any that occur, than something that may happen a year from

now or for all they know, may not happen. So . . . there are

educational advantages of that nature to implementing the plans

immediately" (Transcript 221).

15/ Order of Court of Appeals of July 25, 1969 (Appendix B

to Petition, pp. 38a-39a).- 16 -

submission of the Office of Education plans, with implementa

tion to be left to a later date. All the Court of Appeals

required of these plans for the school year 1969-70 was some

significant action toward disestablishment of the dual school

system" (Appendix E to Petition, p. 78a). it also required

reports by October 1, 1969 of the school boards' programs to

"prepare its faculty and staff for the conversion from the

dual to the unitary system" (Appendix E to Petition, p. 77a).

On August 30, 1969, petitioners applied to Mr. Justice

Black for an order vacating the Court of Appeals' suspension

of its July 3rd order. On September 5, 1969, Mr. Justice

Black denied the application, but stated that his disposition

did not "comport with my ideas of what ought to be done in

this case when it comes before the entire Court. I hope

these applicants will present the issue to the full Court

at the earliest possible opportunity" (Appendix F to Petition,

p. 83a).

Petitioners' petition for writ of certiorari was filed

September 23, 1969, and granted by the Court on October 9.16/1969.

Respondents' cross—petition for writ of certiorari was filed October 8, 1969, and denied October 9, 1969.

17

Summary of Argument

The respondent school districts have had 15 years to solve

the administrative problems which this Court foresaw might

require the granting of "additional time" to those districts

which made a "prompt and reasonable start toward full

compliance" (Brown II, 349 U.S. at 300). But these districts

have done nothing but resist. This resistance has not been

in the form of open defiance? rather, it has been in the form

of adopting the trappings of desegregation rather than the

substance, and in implementing successful tactics for delay.

In this, they have been materially assisted by the district

court. Now, for the first time, the Government has become

an apologist for delay.

If the dual school systems in question are ever to be

successfully disestablished, this court must make it

unmistakably clear that there can be no more delays. But not

only must the Court make the law of the Constitution clear

beyond peradventure, it must also adapt federal equity procedure

to that end: it must act to discourage recalcitrant school

boards from seeking refuge from desegregation in protracted

litigation. In other words, integration, not segregation,

must be the status quo pendente lite.

18

Argument

I

The Time For Delay Of School

Desegregation Has Run Out.

For the past 15 years, each of the respondent school dis

tricts has been on notice that it would have to convert classrooms.

redraw bus routes, and prepare its faculty and staff for the

disestablishment of its dual school system. But for 15 years

these school boards have done nothing but resist disestablish

ment, while Negro school children have waited to realize what,

but for Brown II, would have been their "personal and present"

right to equal protection of the laws. Sweatt v. Painter, 339

U.S. 629, 635 (1950); McLaurin v. Regents, 339 U.S. 637, 642

(1950).

During roughly the first 10 years after Brown I, there was

no litigation pending against these districts, and they did not

see fit to take any steps on their own toward disestablishment

of their dual systems. Once litigation began, they evaded dis

establishment through one delaying tactic after another; from

the pupil placement scheme through grade-a-year plans to "freedom

of choice."

In this, they were materially aided by the district court,

which repeatedly took unwarranted delays in hearing and determin

ing the cases, approved obviously inadequate plans of desegrega

tion, and went so far as to persistently harass civil rights

19

lawyers. In the latest round of litigation, following this

Court’s decision in Green, supra, requiring plans which promise

realistically to work "now” (391 U.S. at 439 (emphasis Court’s)),

the district court refused to schedule an early hearing on peti

tioners’ motions for the adoption of such plans, required the

Court of Appeals to set a deadline for it for hearing the motions,

failed to meet that deadline and then took another 5 months to

uphold the same old, obviously inadequate freedom of choice plans,

insuring that no relief would be possible during the 1968-69

19/

school year.

In this sorry chronicle of footdragging by these school

boards and the district court, the last thing that was needed was

the federal government’s own initiative for delay. Up to August

19, 1969, that had never occurred. But with the letter from the

Secretary of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare of

August 19, 1969, there occurred "a major retreat in the struggle

to achieve meaningful school desegregation" (Statement of the

United States Commission on Civil Rights, p. 2, September 11,

1969) .

17/ See In re R. Jess Brown, 346 F. 2d 903 (5th Cir. 1965); Sand£^.

77 Russell, 401 F.2d 24l"T b th Cir. 1968); United States Commission

on Civil~Rights, Federal Enforcement of School Desegregation,

pp. 39-41, 45-46 (September 11, 1969).

18/ That the district court is capable of moving swiftly is

attested bv the fact that, with the prospects of remaining unre-

^ersed substantial at last, the district court was able to produce

a lengthy opinion in one day — a devastating hurricane n°twith

standing. See opinion of August 26, 1969, Appendix E to Petitio .

19/ For overall progress in school desegregation following this

Court's decision in Green, supra, see Federal Enforcement_of

School Desegregation, supra, p. 36, Chart A.

20

Although the Secretary's letter cited "administrative and

logistical difficulties” requiring delay (Appendix C to Petition,

p. 54a), the Government's witnesses before the district court did

not cite a single specific difficulty with respect to any specific

school system. Rather, they cited, and the district court found,

only the long anticipated need to conduct "the in depth peripheral

studies such as curricular studies and financial studies required

to implement these new plans" (Opinion of the district court of

August 26, 1969, Appendix D to Petition, pp. 64a-65a). Moreover,

the district court found that the delay "would allow collaboration

between the Office of Education and the defendant school districts

to prepare for implementation of the terminal plan, thus result

ing in better education and better community relations and conse

quently, an effective, workable desegregation of the defendant

school districts and the conversion from a dual to a unitary

system" (ibid.).

The following significant colloquy occurred between the

Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Civil Rights Division

and the chief Government witness (Tr. 122):

_ BY MR. LEONARD:

Q. Mr. Jordan, I want to clarify to be sure the

Court and Counsel all understand your position

with respect to the delay. Should the Court

grant a delay, am I clear that it is your posi

tion that even with the delay that in all

likelihood the plans will be very much similar

and that these officials of the school boards

should start to work with the Office of Educa

tion now, in fact by October 1st, to prepare

for the movement from a dual to a unitary

system, is that your position?

21

A. That is correct.

Q. Thank you, that is all.

On or about October 1, 1969, the local school boards reported

to the district court on their progress toward devising programs

to prepare faculty and staff for disestablishment of the dual

systems. These reports indicate that the Government's initiativ

for delay has not failed to produce the predictable effect of ^

inspiring the local boards to adopt a more resistant position.

Moreover, they show that the delay has produced nothing of educa

tional significance. For example, the report of the Sharkey-

Issaquena Line Consolidated School District gives the following

"personalized In-Service Training Program for Staff and Faculty

With Activities To Pectin October 16, 1969, To Prepare Them To

Work or Teach With Those of a Different Race :

District faculty meetings will be held for the

purpose of discussing the problem. Teachers who have

had experience in working in schools and classes

where they were of the minority race will share experiences and ideas with their fellow teachers.

Small discussion group meetings will be held in

each school within the district to afford staff

members time and opportunities for free discussion

and to ask questions. Teachers of both races w n l

continue to work on preparation and ^ i s i o n ° .courses of study. These activities will contribute

to overcoming and removing language barriers among

teachers, students and parents.

90/ For example, in its report to the Court of its program for

libult? preparation? as required by the Court of Appeals' order

of August Is? ?96?? see PP? 16-17, su^ra, the Yazoo County Board

of Education stated that the policies which it ^ l ^ v e s now aovern the elimination of its dual school system are. [F]irot,

9 tSe quaJity of education offered to all of the children in

i ^ d i ^ i c t ; second, ... staff backgrounds and ““ itudes; and

third, and most important, ... community mores and attitudes.

- 22

It is hard to see why these meetings could not have been

conducted in the context of ongoing significant desegregation.

See note 14, suora.

This record therefore reveals that, notwithstanding the

Solicitor General's statement to the Court that the law is clear

that "school boards today are constitutionally obligated to devise

and implement plans that will accomplish [disestablishment] now"

(Memorandum for the United States, p. 4), the law is apparently

not clear to the respondent school boards, the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare, the Department of Justice, the

district court and the Court of Appeals. This Court must there

fore make unmistakably clear that there are to be no more delays:

No more delays to solve "administrative and

logistical difficulties";

No more delays to promote "better community rela-21/

tions";

No more delays for "faculty and student prepara

tion, including various meetings and discussions of

the problems to be presented and the solutions therefor."

This Court should hold "that there is no longer the slightest

excuse, reason, or justification for further postponement of the

time when every public school system in the United States will be

a unitary one" (Opinion in Chambers of Mr. Justice Black, Appendix

F to Petition, p. 81a).

22/ As the Brief Amicus Curiae of the Lawyers' Committee for

Rights Under Law has pointed out, "better community relations often means community resistance.

- 23

This is the only rule of law which will effectively dis

establish the dual school systems: 15 years is enough to solve

administrative problems.

This is the only rule of law which will effectively deal

with the problem of evasion: 15 years is enough to tolerate

defiance of the Constitution.

Petitioners are advertent to the statements ascribed to

the Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Civil Rights

Division that such a declaration by this Court would change

nothing because "Somebody would have to enforce that order.

There just are not enough bodies and people [in the Civil Rights

Division of the Justice Department] to enforce that kind of a

decision" (see Appendix A to Brief Amicus Curiae of the

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law).

There is no little irony in this, for the Government's

initiative for delay has intensified the very resistance it

professes to seek to overcome.

Community hostility to desegregation in these districts

has been placated only at an awful cost: the burdening of both

judicial and administrative enforcement, as local school boards

renew their efforts to clog the courts and the administrative

22/

process with excuses for delay. The possibilities for

fashioning such excuses are enormous, and so any judicial or

22/ For example, in U. S. and Danita Hampton v. Choctaw County

Board of Education, 5th Cir. No. 27297, June 26, 1969, the

Choctaw County, Alabama Board was ordered to abandon freedom of

choice and to adopt a zoning plan. But following the Court of

Appeals' decision below, the board moved the district court for

additional time in which to develop a "workable desegregation

plan," with interim reinstatement of freedom of choice, citing

developments in "adjacent counties" (Choctaw County is on the

Mississippi line). 24

administrative recognition of a justification for further delay

is bound to inspire the wholesale production and assertion of

these excuses. In the long view, delay does not obviate

community hostility; it only creates more persistent and

widespread demands for greater concessions. Merely by the

assertion of these newly inspired claims for delay, adminis

trative and judicial enforcement is impeded.

Petitioners do not doubt that the Civil Rights Division

will be burdened in- attempting to turn back the flood of

renewed litigation. So will the attorneys for the private

plaintiffs, who represent Negro schoolchildren in hundreds

of school desegregation cases throughout the South.

This Court can make administrative and judicial enforce

ment of desegregation work:

M) by making unmistakably clear that the time for

23/

delay has run out; and,

(2) by shifting the burden of litigation from Negro

achoolchildren to the school boards, requiring that integration,

not segregation, be the status quo pendente lite, so that

protracted litigation loses its attractiveness as a tactic

for delaying desegregation.

To the matter of shifting the burden of litigation

petitioners now turn.

23/ This will mean dispelling the notion that there is any

longer a "transition period" during which federal courts or

H.e Iw . may continue to grant delays of desegregation (See

Opinion in Chambers of Mr. Justice Black, Appendix F to Petition.

p. 81a).

25

II

Effective Relief Requires The Immediate

Implementation Of The Previously Submitted

Office Of Education Plans Pendente Lite.

The opinion of Mr. Justice Black as Circuit Justice in this

case states the principles we think ought to govern the Court in

fashioning relief in these cases permanently and pendente liter

... I would hold then that there are no longer any

justiciable issues in the question of making effective

not only promptly but at once — now — orders suffi

cient to vindicate the rights of any pupil in the

United States who is effectively excluded from a

public school on account of his race or color.

It has been 15 years since we declared in the two

Brown cases that a law which prevents a child from

going to a public school because of his color violates

the Equal Protection Clause. As this record conclu

sively shows, there are many places still in this

country where the schools are either "white1 or Negro

and not just schools for all children as the Constitu

tion requires. In my opinion there is no reason why

such a wholesale deprivation of constitutional rights

should be tolerated another minute. ...

Applying these principles to the cases at hand, petitioners

urge that the Court enter a decree which would order:

1. That the Court of Appeals order of August 28, 1969, which

amended its order of July 3, 1969, as modified July 25, 1969, be

reversed and vacated, and the order of July 3, 1969, be affirmed

in part and amended to conform to the principles stated below;

2. That the Court of Appeals be directed to amend its

mandate to the District Court for the Southern District of

Mississippi in order to require th&t pending further litigation

the desegregation plans developed by the United States Office of

- 26

Education and filed in the District Court be implemented imme

diately by the school authorities in these cases (with exceptions

noted in paragraph 3 below);

3. That in the cases of Holmes County Board of Education and

the Meridian Separate School District, where the plans submitted

by the United States Office of Education required delay of desegre

gation until the 1970-71 term, the Court of Appeals forthwith

proceed to enter a pendente lite order requiring immediate desegre

gation under such plans as the Court may devise either with the

assistance of the Office of Education or special masters to be

appointed by the Court of Appeals;

4. That the plans now ordered in accordance with 2 and 3

above will remain in effect pending further litigation in the dis

trict court on the parties1 objections, alternate proposals or

other submissions, and will remain in effect pending appellate

review of any amendments or alternate plans ordered by the dis

trict court, except where amendments are agreed to by the parties;

5. That the Court award costs to petitioners and direct that

the courts below award them reasonable counsel fees.

We believe that the pendente lite immediate relief sought by

petitioners is entirely justified in these cases. In this case

the ultimate problem faced by the Court is the administration of

pendente lite relief since it is inherent in the nature of the

judicial process that one side or the other shall be protected

in its position while litigation is going on toward the end of

determining the parties' ultimate rights. What a court of equity

- 27

must ask Itself is whether the one party or the other should be

put at this risk?

in these cases, first of all, the major evil to which the

defendants might be subjected, should this Court decree immediate

implementation of the H.B.W. plans, would be that they might pre

vail either on their claims in the case of some boards that their

new freedom of choice plans are valid notwithstanding Green v.

o-.-ty school Board. 391 U.S. 430 (1968). or the claims in the

cases of other boards that their plans for assigning pupkls on the

basis of achievement or other tests might be found to satisfy the

requirement of plans which completely disestablish the dual school

system. Both proposition- seem entirely unlikely to be sustained

considering the fact that freedom of choice has produced so little

actual desegregation, and the fact that the school boards so

recently urged in these cases that academic achievement tests

proved the need for and rationality of racial segregation and the

validity of freedom of choice plans resulting in such segregation.

It is true that the disestablishment and later reconstitution of

the dual school system now operated in Mississippi would entail

very considerable inconvenience. But this inconvenience must be

assessed against the probability that defendants can actually

prevail in view of Green. This probability is so low as to be

virtually negligible. The practical difficulty of first following

the H.E.W. plans and then reverting to freedom of choice or

assignments by test scores is therefore virtually negligible and

should be discounted by a court of equity.

28 -

This leaves several questions which the Court in the exercise

of its equitable discretion must take into account in deciding

whether the plaintiffs or the defendants are to suffer in the

interval between the administration of relief at this time and

the final adjudication of all claims. The first concerns the

question whether the present plans are in all practical aspects

the best feasible plans which could be devised. At this point

the issue becomes whether the plans should be put into effect

notwithstanding doubts as to infirmities of this practical

sort with the understanding that these infirmities might be

corrected as time went on or whether, on the other hand, its

putting into effect is to be delayed until such time as they

shall be judged by this Court to be the best plans devisable by

the wit of man. This question seems to answer itself, above

all, for the reason that it lies in the nature of practical

equitable relief that in any event, no matter how carefully a

plan might be devised, from time to time a court of equity,

either by its very nature or by the customary reservation of

discretion to grant further relief at the foot of a decree,

might desire to modify and mold relief to suit circumstances

thatarise subsequent to the awarding of relief, or to answer

difficulties which were not felt when the relief was awarded but

which have subsequently made themselves apparent.

in putting into effect the H.E.W. plans, which are by far

the best validated plans before this Court, the Court would be

doing very little, if anything, more than any court of equity

29

is forced to do when. as in this case, it is ineluctably forced

into the position of administering detailed relief, unless xt

desires to endure the protracted frustration of constitutional

or other established legal rights.

It will be argued that the school boards have not had a full

opportunity to litigate their objections to the H.E.W. plans.

This is true. But the question is whether pending such lxtiga-

tion these plans should be ordered into effect. They carry

with them considerable validation, including testimony by

government witnesses, as to their adequacy. Petitioners will

file sufficient copies of the plans so that all members of the

Court may have copies. The H.E.W. plans indicate how many pupils

of each race will attend each school and it is apparent that sub

stantial desegregation will result. In contrast, the school

boards' plans leave the future of desegregation in each school

district entirely nebulous and the degree of progress, if any,

entirely unpredictable.

There remains the. question of the interruption of the school

year. Here, too, there are extremely important values to balance

by this Court. It is doubtless true, and petxtxoners here con

cede, that the educational process, very narrowly considered,

will be slightly delayed or impeded by the interruption of the

school year for the purpose of bringing about a compliance with

the judgment of this Court which was entered 15 years ago, and of

bringing about the enjoyment by these petitioners of thexr rights

which have been denied to an entire generation of school chxldrea

30 -

But in tailoring and molding its relief, a court of equity is

surely empowered and even obligated to take into account the fact

that there is an educational dimension of another sort, that what

might be learned from this process is that at long last the con

stitutional rights of American children — white and colored —

must be given effect. This is a court of equity. And it is a

court which at the present juncture must, on its own, balance the

factors leading to and detracting from the decision to administer

relief pendente lite in favor of the present petitioners. Surely

such a court in such a position may take into account the educa

tional value just adverted to. On the practical level, it is not

entirely clear how much difference it makes whether a change is

made in September or in October in the total absence of any show

ing in the present record beyond generalized assertions of

difficulty. The decision of this Court ought to be not to deny

the plainly established constitutional rights of these children

on a conjectural basis, both qualitatively and quantitatively,

but rather to insist upon their enforcement until contrary con

siderations are found to justify a suspension of the processes

of enforcement. The assumption up to now has been for 15 years

that every difficulty, conceptual and factual, must be overcome

before these children enjoy their constitutional rights. Peti

tioners submit earnestly that the presumption from now on should

be that those situated as these petitioners now are ought to enjoy

their constitutional rights unless and until convincingly, and

through all the processes of appeal, it is demonstrated and finall

adjudicated that some weighty reason exists why they shall not.

- 31 -

in two of the cases (Meridian and Holmes County) the H.E.W.

plans do not provide for immediate complete relief but embrace the

philosophy of deliberate speed and provide for delay until further

school construction is completed. We urge, for the reasons stated

previously, that all such delays for solution of administrative

obstacles to desegregation be rejected. Such delays urged by

school districts or the Department of H.E.W. are no longer jus

ticiable. In this situation, we urge that this Court remand the

matter with directions that the experienced panel of the Court

of Appeals which is hearing this matter order immediate desegre

gation under plans to be devised with the assistance of H.E.W.,

if it is forthcoming, or without such aid if that is necessary,

by the use of either special masters selected by the court or

2A /experts provided by the petitioners.

Only such delays as are demanded by the time needed for the

judicial process to function should be permitted. The more normal

course of remanding this detail work to the district courts should

be avoided in this instance because of the incredible history of

delay and frustration of the Brown decision which the District

Court for the Southern District of Mississippi has countenanced.

The Court of Appeals itself has felt the need to fashion detailed

decrees to deal with that reality.

24/ Where school authorities refused to provide expert assistance

in developing desegregation arrangements Judge Bohanon accepted

the offer of plaintiffs to furnish an expert educational panel.

See Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public^ Schools,

244 F. supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), affirmed 375 F.2d 158 (10th

Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 387 U.S. 931 (1967). Such expert assist

ance will be provided by petitioners in these cases if needed.

32

We are now at the turning point in the history of school

desegregation. Forceful and decisive action taken now by this

Court can rally the lower courts and the executive to finish the

process of school desegregation begun 15 years ago. Retreat at

this critical juncture would pose a threat to the rule of law this

Nation could ill afford.

Fortunately, the task is amenable to judicial solution. What

is needed is to excise from the law earlier-tolerated justifica

tions for delay and to assert the traditional equity function of

the federal courts in such a way as to discourage, once and for

all, resort to protracted litigation as a safe haven for the dual

school system.

- 33 -

r

Conclusion

Petitioners pray that the judgment below be reversed

and the relief prayed for herein be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN C. AMAKER

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

MELVYN ZARR10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

REUBEN ANDERSON

FRED L. BANKS, JR.538̂ . North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

CHARLES L. BLACK, JR.

169 Bishop Street

New Haven, Connecticut 06511

Attorneys for Petitioners

34