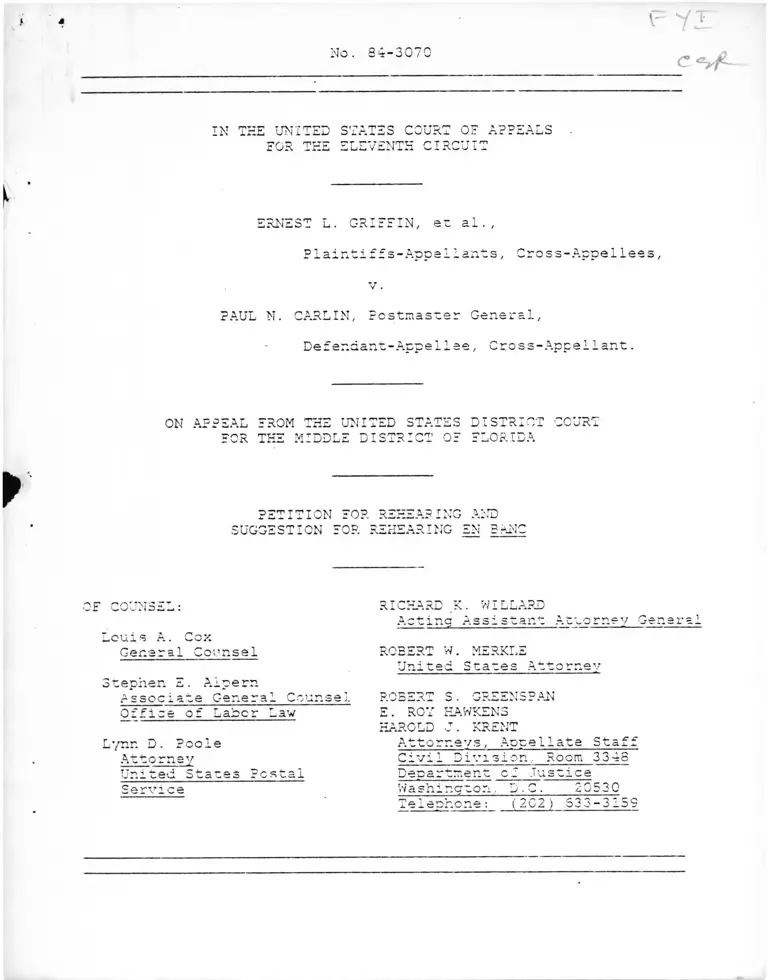

Griffin v. Carlin Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

May 17, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Griffin v. Carlin Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc, 1985. de71f9ac-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/990d221b-a57f-4617-9542-7df467cac7e7/griffin-v-carlin-petition-for-rehearing-and-suggestion-for-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

J v-

No. 84-3070 c < ^ f ~

IN THE UNITED

FOE THE

STATES COURT OF APPEALS

ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

ERNEST L. GRIFFIN, e: al . ,

Plaintiffs-Appallants, Cross-Appellees,

v .

PAUL N. CARLIN, Postmaster General,

De f endant-Appellee, Cross-App e11 ant.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

PETITION

SUGGESTION

FOR REHEARING AND

OR REHEARING SN BANC

OF COUNSEL:

tour s A . Cox

General Counsel

Stephen E. Aipern

Associate General Counsel

Office of Labor Law

Lynn D. Poole

Attorney

United Stares Postal

Service

RICHARD K. WILLARD

Actinq Assistant Attorney Ge

ROEERT W. MERKLE

United Stares Attorney

ROBERT 3. GREENSPAN

E . ROY HAWKENS

HAROLD J . KRENT

Atto m e vs, Appellate Staff

Civil Divi sion. Room 3348

Department cl Justice

Washington . D.C. 20530

TeIeohcne: (202) S33-315S

- 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

STATEMENT OF COUNSEL REGARDING EN BANC SUGGESTION..............

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES.............................................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE COURSE OF PROCEEDINGS AND

DISPOSITION OF THE CASE............................................ 2

FACTS.................................................................... 2

ARGUMENT................................................................ 6

T. THE PANEL SUBVERTED ACCEPTED TITLE VTI

PRINCIPLES BY TRANSFORMING A DISPARATE TREATMENT

CASE INTO A DISPARATE IMPACT CASE, THEREBY SHIFTING

THE BURDEN TO THE EMPLOYER TO DEMONSTRATE THE

VALIDITY OF ALL FACETS OF ITS EMPLOYMENT

PRACTICES......................................................... 6

II. THE PANEL ERRED BY RULING THAT THE DISPARATE

MODEL CAN BE USED TO CHALLENGE SUBJECTIVE PROMOTION PROCEDURES AND THE FINAL RESULT OF THE

OVERALL PROMOTION PROCESS.............................. .11

CONCLUSION............................................................. 15

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE.............................................. 15

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases :

Allen v. Prince George's County, 7 37 F.2d

] 2 99 (4 th C ir . 19S4 .............................................. 4

Anderson v. City of Bessemer, 105 S. Ct. 1504

( 1985 ............................................................... 4

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 ( 19821.................... 12

Contreras v. City of Los Angeles, 656 F . 2d

1267 (9th Cir. 1981), cert. denied , 455

U.S. 1021 (1982 )................................................ 14

Dot ha rd '7. Raw 1 i ns o n , 433 U.S. 321 ( 19 7 7).................6,12

Furnco Construction Co. v. Waters, 4 3 8 U.S. 567

. ................................................................ 14

General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125

( ................................................................... 1 2

'* Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971 )..........5,6 , 12

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977 )........................ 6,1 2

* McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792( 19 7 3 ................................ 2 ,7 , 1 3

Pope v. City of Hickory, 679 F.2d 20 (4th Cir.

198 2 )............................................................... q

Porter v . Adams, 639 F.2d 273 (5 th Cir. 1981).............. 10

* Pouncy v. Prudential Insurance Co., 668 F .2d 795

(5th Cir. 19«2)............................................... 9 '13

* Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (198 2).............. 4

Robinson v. Polaroid Corp., 732 F .2d 1010

( 1 st Cir. 1984 ).................................................. 9

Segar v. Smith, 7 38 F.2d 1249 (D.C. Cir. 1984),

petit ion for c e r t . filed ................................. 5,8,11

* Texas Department of Community Affairs v.

Bu rd i ne , 450 U.S. 248 (1Q81).......................... 2,6,8,14

Statute and Regulation:

Title v x i ............ pass lm

* Cases and authorities chiefly relied upon are rnarked by

asterisks.

- i i i -

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-3070

ERNEST L. GRIFFIN, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants, Cross-Appellees,

v.

PAUL N. CARLIN, Postmaster General,

Defendant-Appellee, Cross-Appellant.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLQRIDA

PETITION FOR REHEARING .AND

SUGGESTION FOR REHEARING SN BANC

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1) Whether an employer in a Title VII disparate treatment

class action, to rebut plaintiffs' claim of purposeful

discrimination based on a statistical disparity, must bear the

burden of identifying and then validating all practices which

conceivably might explain the statistical disparity even though

plaintiffs have not alleged that any specific practice

violates Title VII under a disparate impact theory.

2) Whether under the disparate impact model, the employer

must bear the burden of validating both subjective promotion

procedures and the final results of the overall promotion

process.

STATEMENT OF THE COURSE OF PROCEEDINGS

AND DISPOSITION OF THE CASE

At stake in this case is the orderly and just administration

of Title VII litigation. Complex, class-wide suits require

courts to engage in careful analysis and evaluation of the

evidence in accord with the substantive principles of law

underlying the statute. The panel in this case departed from

these principles in ways that not only caused it to reach the

wrong result in this case, but also will have seriously harmful

effects on the conduct of future Title VII litigation. The-

oanel simply ignored the method of-proof for disparate treatment

cases prescribed in Texas Department of Community Afiairs v.

Burdine, 450 U.S. 248 (1381), and McDonnell Douglas Coro, v.

Green, 411 U.S. 732 (1373), and formulated insread a conflicting

analytical framework that automatically converts a disparate

treatment case into a disparate impact case whenever plaintiffs

base their allegations of purposeful discrimination on a

statistical disparity in the workforce.

FACTS

Plaintiffs, black employees of the United States Postal

Service at Jacksonville, Florida, commenced the instant Title

VII action on July 7, 1372. They alleged that the Postal

Service discriminated in making assignments and promotions,

although they did not specify any employment practice in

particular which adversely affected the opportunities for blacks

to advance in the Postal Service hierarchy. The district court

certified a class consisting of black employees at the

Jacksonville Post Office and all black applicants and

2

Afterprospective applicants for employment at that office.

much discovery and intervening events not directly relevant to

this petition, a consolidated amended complaint was filed on

November 12, 1931. Slip op. at 2770.^

On September 8, 1982, the district court dismissed

plaintiffs' disparate impact claims on the ground that

plaintiffs’ pleadings had failed to apprise the Postal Service

as to which employment practices would be challenged on this

theory. The court reasoned chat

none of plaintiffs' pleadings have put

defendants on notice as to which employment

practices will be challenged on this theory.

Sven plaintiffs' resoor.se to the pending

Morion to Dismiss does not allege which

practices would be so challenged * * *.

Plainriffs have had ample opportunity to give

defendants such notice and yet they have not

done so. There is no question but than

defendants would be grossly prejudiced if

plaintiffs were allowed to proceed under this

theory [(emphasis supplied) (R.E. 141).]

The court also held that in any event, only objective, facially

neutral employment practices could be challenged on a disparate

impact theory. The case thus proceeded to trial under a

disparate treatment theory. Slip op. at 2771.

In the same order, the district court dismissed the portion

of plaintiffs' complaint that challenged use of written tests in

the promotion process because plaintiffs had failed to exhaust

administrative remedies as to the testing issue. The panel has

reversed the district court on that issue. Slip op. at 2774.

2 Before trial, the Postal Service made a continuing effort to

understand the nature of plaintiffs' disparate impact claims.

It filed an interrogatory requesting detailed information on

these impact claims, and plaintiffs responded that they would

answer when they had more information (R. at 2292). Defendants

consequently filed objections to this answer, but withdrew that

objection on plaintiffs' assurance that they would respond "when

they have the information available to do so." R. at 2303.

Plaintiffs never responded.

The district court ultimately found that the Postal Service

did not discriminate systematically against blacks seeking

supervisory positions. The Court found the Postal Service's

statistical evidence to be more credible than plaintiffs', and

it discounted plaintiffs' anecdotal evidence of purposeful

discrimination.

A panel of this Court reversed in part. With respect to

plaintiffs' disparate treatment claim, the panel held that the

district court erred in discrediting plaintiffs' statistics

3 _concerning promotional decisions. Slip op. at 2777-2778.

The panel's disparate treatment holding gave little or no

weight to the careful findings of the district court in its 302

page opinion. See R.E. at 148-449. The district court, in

weighing the probative value of two sets of statistics with

respect to the appropriate labor pool, necessarily made

credibility judgments in ruling for the Postal Service. It was

for the trial court to decide, given the availability of "other,

better, evidence in the form of applicant flow analyses," what

weight to give the testimony proffered by both sides. Allen v.

Prince George's County, 737 F.2d 1299, 1305 (4th Cir. 1984).

As the Supreme Court has made clear:

[D ]iscriminatory intent is a finding of fact

to be made by the trial court; it is not a

question of law and not a mixed question of

law and fact * * *.

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 289-290 (1982).

See also Anderson v. City of Bessemer, 105 S. Ct. 1504

(1985). But the panel viewed the conflicting testimony on

statistics as presenting "a matter of law," slip op. at 2778,

and thus made a de novo finding as to the appropriate labor

pool. The panel, therefore, clearly erred under Pullman-

Standard in supplanting the trial court's evaluation of the

evidence presented. This manifest abuse of the "clearly

erroneous" standard presents an additional ground for en banc

review.

In fact, the panel seemingly ignored the findings of the

district court when it remanded the disparate treatment claim

(CONTINUED)

The panel instructed the district court on remand to apply the

analysis that was recently formulated by the D.C. Circuit in

Seqar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249 (D.C. Cir. 1934), petition for

cert. filed. Specifically, if plaintiffs on remand establish a

prima facie case of disparate treatment, the burden will shift

to the Postal Service not only to explain ohe disparity by

reference to facially neutral business procedures, but to

demonstrate the validity of those practices under a disparate

impact analysis. Slip op. at 2778-2781.

Finally, the panel held that the disparate impact model

could be used to challenge not only objective standards but also

subjective promotion procedures, such as interviewing,

recommendations, and the like. The panel emphasized that Title

VII requires the elimination of all "artificial, arbitrary, and

unnecessary barriers to employment." Slip op. at 2775-2773.

Because either subjective selection procedures or the

interaction of multi-component selection procedures may create

arbitrary and unnecessary barriers to employment, the Court

concluded than such procedures’ should be subject to disparate

impact challenges. Id.

J (FOOTNOTE CONTINUED)

for the district court to consider the craft work force

statistics. Slip op. at 2773. The district court had already

concluded that "[e]ven if plaintiffs' statistical study were

reliable and credible * * * the Court could draw no inference of

intent to racially discriminate in promotions by the

Jacksonville Post Office from the results." R.E. at 436.

5

ARGUMENT

I. THE PANEL SUBVERTED ACCEPTED TITLE VII PRINCIPLES

BY TRANSFORMING A DISPARATE TREATMENT CASE INTO A

DISPARATE IMPACT CASE, THEREBY SHIFTING THE BURDEN

TO THE EMPLOYER TO DEMONSTRATE THE VALIDITY OF ALL

FACETS OF ITS EMPLOYMENT PRA.CTICSS.

The substantive principles of law underlying Title VII

recruire that disoarate treatment claims and disparate impact

claims be analyzed differently. When class-wide claims of

disparate treatment are in issue, "[p]roof of discriminatory

motive is critical." International Brotherhood or Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324, 335 n.15 (1977). In contrast,

the employer's motive is irrelevant in a disparate impact case.

Id. at 335. Once plaintiffs have shown that a particular

employment practice has a disparate impact, thereby establishing

a prima facie case, the employer will be held liable unless it

can justify that practice on the basis of business necessity.

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321, 329 (1977); Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 430 (1971). The panel, by

automatically converting a disparate treatment case into a

disparate impact case and then placing the burden on the

employer to prove the business necessity of facially-neutral

employment practices, has seriously distorted well-established

Title VII analysis.

The panel's ruling conflicts with the Supreme Court's

careful description of the method and order of proof to be

followed in disparate treatment cases. In 3urdine, the Court

explained that the burden on the defendant is "to rebut the

presumption of discrimination [raised by plaintiffs' prima facie

case] by producing evidence that the plaintiff was rejected, or

6

someone else was preferred, for a legitimate, nondiscriminatory

reason." 450 U.S. at 254. The Court then held that if the

employer presents "a legitimate reason for the action" the

burden shifts back to the plaintiff to show that the proffered

reason was not the true reason for the employment decision, but

was a pretext for discrimination. 450 U.S. at 255-256; see also

McDonnell Douglas Coro, v. Green, supra. This method of proof

nowhere contemplates a remairenien'c that the employer show the

business necessity of the legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason

for the employment decision. Indeed, the panel's decision

effectively eliminates the burden placed upon plaintiffs by

McDonnell Douglas to prove pretext.

In determining whether a practice asserted by an employer as

a defense to a disparate treatment charge is a legitimate,

nondiscriminatory reason for the observed disparity, the court

may properly evaluate the reasonableness of the practice. But

the purpose of that inquiry is simply to determine whether the

employer had, in fact, intentionally discriminated against

plaintiff -- i.e., whether the asserted practice was legitimate,

or merely a pretext for discrimination. Under the panel's

ruling, however, the evaluation of the asserted employment

practice is not limited to this inquiry. Instead, it wrongly

changes the focus of the inquiry from whether purposeful

discrimination occurred to whether there is a business necessity

for the practice. Without the foundation of a disparate impact

case -- in which plaintiffs identify, plead, and present

evidence that a particular employment practice has a disparate

impact on a protected class -- there is no legal basis for

7

requiring the employer to prove the business necessity of a

A.facially neutral practice.*

The panel's revision of the Surdine analysis, as even it

acknowledged, slip op. at 2774, conflicts with the rule in most

other circuits. See Pouncy v. Prudential Insurance Co., 668

F.2d 795 (5th Cir. 1982); Robinson v. Polaroid Corn., 732 F.2d

1010, 1014 (1st Cir. 1934); Pose v. City of Hickory, 679 F.2d

20, 22 (4th Cir. 1982). These circuits recognize that "[t]he

discriminatory impact model of proof in an employment discrimina

tion case is not * * * the appropriate vehicle from which to

launch a wide ranging attack on the cumulative effect of a

’ Indeed, the burden imposed upon the employer in this case is

greater than that imposed by the D.C. Circuit in Segar v.

Smith, supra. There, the Court held that:

[W]hen an employer defends a disparate

treatment challenge by claiming that a

specific employment practice causes the

observed disparity, and this defense

sufficiently rebuts the plaintiffs' initial

case of disparate treatment, the defendant

should at this point face a burden of proving

the business necessity of the practice.

[Emphasis supplied. 738 F.2a at 1270.]

In Griffin, unlike Segar, defendants never relied on any

specific employment practice to explain the statistical

imbalance. The Postal Service chose instead to rebut

plaintiffs' claims of intentional, systematic discrimination by

analyzing those aspects of the promotion process most completely

subject to the control of the Jacksonville Post Office, that is,

promotion after employees attained the hiring register. When

defendants demonstrated that there was no discrimination in that

area, they rested, and did not attempt to identify a cause or

causes for the disparities identified by plaintiffs. In

applying the Segar analysis to the circumstances of this case,

the panel therefore is requiring the Postal Service not only to

justify the employment practices that caused the statistical

disparity, but to identify those practices that conceivably

could have contributed to the disparity. In essence, the panel

is requiring the Postal Service to make a prima facie disparate

impact case for plaintiffs, and then rebut it.

8

company's employment practices. Pouncy, supra, 668 F.2d a

800. If plaintiffs wish to use the disparate impact model, they

must identify a particular practice and present evidence showing

that it has a disproportionate, adverse effect on them or

members of their class. See Pope v. City of Hickory,

5sunra.

The panel's ruling also undercuts an important goal of Title

VII by virtually eliminating the possibility for conciliation

between plaintiffs and employers. Porter v. Adams, 639 F.2d

273, 277 (5th Cir. 1981) ("conciliation, rather than litigation,

is a recognized goal of Title VII"). A carefully constructed

administrative process has been made a prerequisite to bringing

suit so that, to the extent possible, differences can be worked

D Moreover, the practical difficulties that this rule would

cause in other federal employment cases are enormous. Virtually

all employment qualification determinations in the federal civil

service, whether for initial placement, promotion, or entry into

training programs, are based on minimum qualification standards

published by OPM. The panel's ruling could place at issue the

validity of innumerable qualification standards, with the

consequent staggering expense of validation of such standards,

even in the absence of any challenge to those standards under a

disparate impact theory. Litigation against any individual

agency would threaten the employment practices of the entire

government, because the Court's ruling could require a federal

agency to show the business necessity of a standard prescribed

government-wide by OPM. When objective employment

qualifications are published, and thus readily available to

plaintiffs, and plaintiffs have not charged or proved that any

such practice violates Title VII under a disparate impact

theory, there is no justification for imposing such burdens on

the government as an employer.

So, here, too, the Postal Service publishes employment

qualifications, and they are readily available to plaintiffs.

The expense of validating these qualifications would be

substantial, see infra, and the mere expense could very well

serve as a disincentive to the Postal Service to derend Title

VII actions even when such course of action is in the public

interest.

9

out informally between employer and employee without resort'to

litigation. The panel's theory, allowing conversion of a

disparate treatment case to a disparate impact case in mid

trial, circumvents the administrative process and the

possibility of conciliation between employee and employer prior

to trial. Indeed, because the panel's opinion does not require

plaintiffs to identify any particular employment practice at

all, it renders the exhaustion requirement all but

superfluous. See Brown v. General Services Administration,

425 U.S. 320, 332 (1976).

Thus, the court of appeals' ruling automatically converting

a disparate treatment case into a disparate impact case in the

midst of litigation will have an immediate and crippling effect

on orderly procedure and fair resolution of Title VII .cases.

Here, for instance, the Postal Service will have the cumbersome

task of determining what led to the statistical disparity and

then validating all potential factors, even though plaintiffs

have reoearedly failed to identify any practices as violative of

Title VII. This would require the Postal Service to ascertain

which of its numerous tests and/or registers, or other possible

qualification standards, interview processes, considerations

regarding experience, seniority, discipline or attendance might

be responsible for the statistical imbalance.

There is no need to speculate about the added burden that

the Postal Service would have to bear in defending this lawsuit

if, as the panel held, plaintiffs could convert the disparate

treatment case into a disparate impact case. The district court

specifically found that "defendants would be grossly prejudiced

10

if plaintiffs were allowed to proceed under [a disparate impact]

£theory." R.E. at 141. But under the panel's analysis,

"gross prejudice" is apparently irrelevant to the inquiry. In

the face of a statistical disparity, employers must as a matter

of course identify and validate all employment practices which

conceivably contribute to the disparity, despite the possible

prejudice. That plaintiffs in this case repeatedly failed to

identify which practices they were challenging is of no concern

to the panel. Thus, the enormous expense and difficulties for

employers, and particularly the federal government, that will be

caused by the rule announced by the panel argues scrongly for en

banc review.^

II. THE PANEL ERRED BY RULING THAT THE DISPARATE IMPACT

MODEL CAN BE USED TO CHALLENGE SUBJECTIVE PROMOTION

PROCEDURES AND THE FINAL RESULT OF THE OVERALL

PROMOTION PROCESS.

The

applies

greater

panel's holding that the disparate impact analysis

to subjective promotion procedures places an even

burden upon the employer. According to the panel, upon

The expense of validating tests and procedures long since

abandoned will be an enormous financial burden, one which may

well chill the Postal Service's litigation efforts. The Postal

Service informs us that it reported to the court in Contreras v.

Carlin, Mo. C-82-560S (C.D. Cal.), that the expense of

validating three tests alone amounted to approximately two

million dollars. By imposing such a burden on employers, the

panel's decision unfairly skews the course of the litigation.

7 A petition for certiorari is currently pending m Segar. We

will inform the Court of any further action raken in that

case. While we believe that the weighty issues implicated in

the panel's decision warrant further review, at a minimum, this

Court should hold the instant petition pending the Supreme

Court's disposition of the Segar petition.

11

plaintiffs' presentation of a prima facie case based upon

statistical disparity, the defendant must not only identify and

defend the validity of all pertinent objactive'promotion

practices, it must identify and validate subjective practices as

well. That burden is not only contrary to Supreme Court

precedent, but it simply is unworkable.

The Supreme Court first developed a discriminatory impact

analysis in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra■ There an

employer used objective personnel selection devices — an

education requirement and standardized tests — to select

employees. Similarly, every other Supreme Court disparate

impact case of which we are aware has involved an objective

selection device, or rule, used to classify applicants or

employees for the purpose of making personnel decisions. See,

e.g., Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982) (written

examination); General Electric Co. v. GiIbert, 429 U.S. 125, 137

140 (1976) (exclusion of disabilities due to pregnancies from

disability plan); Doth'ard v. Rawlinson, supra, 433 U.S. at 328-

332 (height and weight requirements). Conversely, where

subjective decisions are involved, the Court has employed the

disparate treatment model. See, e.g., International Srotnernood

of Teamsters v. United States, supra.

Indeed, the Supreme Court has stressed that subjective

factors simply cannot be analyzed within the disparate impact

framework. In McDonnell Douglas Coro, v. Green, supra, 411

U.S. at 806, an employee alleged that the employer refused to

hire him because of his prior involvement in civil rights

activities, and he alleged that the employer structured its

12

hiring policies so

vacating the court

that the disparate

subjective busines

as to exclude qualified black applicants,

of appeals decision, the Court emphasized

impact analysis is not applicable to

s decisions:

In

But Griggs differs from the instant case in

important respects. It dealt with

standardized testing devices which, however

neutral on their face, operated to exclude

many blacks who were capable of performing

effectively in the desired positions. * * *

[Here, the employer] does not seek [the

applicant's] exclusion on the basis of a

testing device which overstates what is

necessary for competent performance * * *

and,.in'the absence of proof of pretext or

discriminatory application of such a reason,

this cannot be thought the kind of

"artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary

barriers to employment" which the Court found

to be the intention of Congress to remove.

411 U.S. at 306. Therefore, in

subjective practices, the Court

impact model is inappropriate.

evaluating an employer's

has held that the disparate

See also Bouncy, supra, 668 F.2d

at 800-801.

Moreover, because there is no accepted method of validating

subjective business practices, the panel's decision is simply

unworkable. The employer would presumably be forced to identify

each component of the promotion process -- interviewing,

recommendations, private encouragement -- and then demonstrate

the business necessity of each step along the way. The panel

nowhere explains how interview evaluations can possibly be

validated. The panel's rule therefore invites courts to second

guess managerial discretion. See generally Burnco Construction

Co. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567, 576-578 (1978). Subjective

standards and practices, which by their nature leave much

discretion to expert personnel judgments are not susceptible of

validation in the same way that test scores, or height or weight

limitations are, and in some instances may not be susceptible to

validation at all. As the Supreme Court counselled in Burdine,

supra, Title VII was "not intended to 'diminish traditional

management prerogatives.'" 450 U.S. at 259 (creation omitted).

See also Contreras v. City of Los Angeles, 656 F.2d 1267, 1278

(9th Cir. 1981) ("[t]he legislative history, of Title VII

clearly reveals that Congress was concerned about preserving

employer freedom, and that it acted eo mandats employer color

blindness with as little intrusion into the free enterprise

system as possible"), cert. denied, 455 U.S. 1021 (1982).

In sum, the panel has drastically shifted the allocation of

burdens in Title VII cases and, in so doing, has effectively

abolished the well-established distinction beteween the

disparate treament and disparate impact models. Pursuant to the

panel's decision, whenever plaintiffs assert a statistical

disparity, the employer must identify all factors, both

objective and subjective, which may have contributed to that

disparity, and then sustain an additional burden of validating

each factor identified. Under the panel's analysis, a

conclusion of discrimination may in essence reflect no more than

an employer's failure to prove business necessity for each step

of the promotion process.

14

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the Court should grant rehearing

or rehearing en banc.

Respectfully submitted,

OF COUNSEL:

Louis A. Cox

General Counsel

Stephen E. Alpern

Associate General Counsel

Office of Labor Lav

.Lynn D. Poole

Attorney

United States Postal

Service

RICHARD K . WILLARD

Acting Assistant Attorney General

ROBERT W. MERKLE

United States Attorney

ROBERT S. GREENSPAN

E . ROY HAWKENS

HAROLD J . KRENT

Attorneys, Appellate Staff

Civil Division, Room 3348

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

Telephone: (202) 633-3159

MAY 1985 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 17th day of May, 1985 I served

a copy of the foregoing Fetition for Rehearing and Suggestion

for Rehearing En Banc upon Plaintiffs-Appellants, Cross-

Appellees by causing copies to be mailed, postage prepaid, to:

Charles S. Ralston, Esquire

Gail J. Wright, Esquire

Penda Hair, Esquire

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013-2815

B. Walter Kyle, Esquire

1248 West Edgewood Avenue

Jacksonville, Florida 32208-2768

f HAROLD J. KRENT

Attorney

15

STATEMENT OF COUNSEL REGARDING EN 3ANC SUGGESTION

1. I express a belief, based on a reasoned and studied

professional judgment, that the panel decision is contrary to

the following precedents of. the Supreme Court: Texas Department

of Community Affairs v. Surdine, 450 U.S. 248 (1981), and

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v . Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973).

2. I further express a belief, based on a reasoned and

studied professional judgment, that this appeal involves

questions of exceptional importance:

a) .Whether an employer in a Title VII

disparate treatment, class action, to rebut

plaintiffs' claim of purposeful

discrimination based on a statistical

disparity, must bear the burden of

identifying and then validating all practices

which conceivably might explain the

statistical disparity even though plaintiffs

have not alleged that any specific practice

violates Title VII under a disparate impact

theory.

b) Whether the disparate impact model can be

used to challenge subjective promotion

procedures and the final results of the

overall promotion process.

■HAROLD JV KRENT

Attorney of Record

for the United States

GRIFFIN v. CARLIN 2767

Ernest L. GRIFFIN, et al„

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Cross-Appel lees,

v.

Carl CARLIN. Postmaster General.

Defendant-Appellee,

Cross-Appellant.

No. 84—3070.

United States Court of Appeals,

Eleventh Circuit.

March 28, 1985.

Black employees and former employ

ees of certain post office brought Title VII

action alleging, inter alia, discrimination in

promotions. The United States District

Court for the Middle District of Florida,

Susan H. Black, J., certified the suit as a

class action, dismissed plaintiffs’ challenge

to written tests used in promotion process,

and all disparate impact claims and found

no disparate treatment in promotions,

awards, discipline and details, and cross

anpeals were taken. The Court of Appeais,

Tuttle, Senior Circuit Judge, held that: (1)

disparate impact theory could be used to

challenge end result of multicomponent

promotion process and to challenge subjec

tive elements of that process; (2) craft

work force was the appropriate labor pool

rather than supervisory register for pur

poses of determining whether plaintiffs’

statistics established a prima facie case of

disparate treatment; furthermore, if, on

remand, plaintiffs were able to establish

prima facie case, defendants could not re

but the presumption of discrimination by

reliance on the supervisory registers or

written tests unless those procedures had

been validated as required under a dispar

ate impact analysis; (3) third-party com

plaint couid serve as administrative basis

for the suit; and (4) district court did not

abuse its discretion in certifying the suit as

a class action.

Reversed in part, affirmed in part, and

remanded.

1. Civil Rights ®=>38

Judicial complaint in Title VII action is

limited to scope of the administrative inves

tigation which could reasonably be expect

ed to grow out of the charge of discrimina

tion. Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 701 et

seq., as amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e et

seq.

2. Civil Rights <5=38

Postal Service employee’s administra

tive complaint, which charged that quali

fied blacks were being systematically ex

cluded in training and development and op

portunities for advancements, challenged

aspects of Postal Service's employment

practices which would reasonably include

testing; thus, trial court erred in dismiss

ing portion of employee’s complaint chal

lenging use of written tests as a condition

of promotion for failure to exhaust admin

istrative remedies. Civil Rights Act of

1964, § 701 et seq., as amended. 42 U.S.

C.A. § 2000e et seq.

3. Civil Rights 3=9.10

Disparate impact theory could be used

to challenge end result of multicomponent

promotion process and to challenge subjec

tive elements of that process. Civil Rights

Act of 1964, § 701 et seq., as amended, 42

U.S.C.A. § 2000e et seq.

Synopsis. Syllabi and Key Number Classification

COPYRIGHT D 1985 by WEST PUBLISHING CO.

The Synopsis. Syllabi and Key Number Classifi

cation constitute no part of the opinion of the court.

2768 GRIFFIN v. CARLIN

4. Civil Rights <2=43

In a disparate treatment case proof of

discriminatory motive or intent is essential.

Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 701 et seq., as

amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e et seq.

5. Civil Rights <5=43. 44(1)

Prima facie case of disparate treat

ment may be established by statistics alone

if they are sufficiently compelling and the

prima facie case is enhanced if plaintiff

offers anecdotal evidence to bring the cold

numbers convincingly to life; once plaintiff

establishes prima facie case of disparate

treatment, burden shifts to defendant to

rebut the inference of discrimination by

showing plaintiffs statistics are misleading

or by presenting legitimate nondiscrimina-

tory reasons for the disparity and if de

fendant carries that burden, presumption

raised by prima facie case is rebutted and

plaintiff must prove that the reasons of

fered by employer were pretextual. Civil

Rights Act of 1964, § 701 et seq., as

amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e et seq.

6. Federal Courts <5=850

Reviewing court may not reverse deci

sion of district court unless court's findings

of fact, whether subsidiary or ultimate

fact, are clearly erroneous or court erred

as a matter of law.

7. Civil Rights <5=44(4)

Federal Courts <£=955

Where’ promotions to supervisory posi

tions in Postal Service were made almost

exclusively from internal work force based

in part on craft work force experience craft

work force was the appropriate labor pool

rather than supervisory register for pur

poses of determining whether plaintiffs’

statistics establish a prima facie case of

disparate treatment; furthermore, if, on

remand, plaintiffs were able to establish

prima facie case, defendants could not re

but the presumption of discrimination by

reliance on the supervisory registers or

written tests unless those procedures had

been validated as required under a dispar

ate impact analysis. Civil Rights Act of

1964, § 701 et sea., as amended, 42 U.S.

C.A. § 2000e et seq.

8. Civil Rights <£=44(4)

In disparate treatment case alleging

discrimination in Postal Service’s system

for promotions to higher, level supervisory

positions and to nonsupervisory positions,

trial court’s findings that plaintiffs’ statis

tics and those promotions showed a mix of

positive and negative deviations and that

such results were typical of nondiscrimina-

tory environment were not clearly errone

ous; furthermore, trial court’s findings

that blacks were not discriminated against

in giving of awards and that race was not a

statistically significant factor in the imposi

tion of discipline were not dearly errone

ous. Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 701 et

seq., as amended. 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e et

seq.

9. Federal Courts <s=951

If, on remand, district court found a

pattern or practice of discrimination

against class of black employees and for

mer employees of Postal Service, that

should be taken into consideration in

court's evaluation of individual claims.

Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 701 et seq., as

amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e et seq.

10. Civil Rights <5=32(1)

Prerequisite to filing of Title VII law

suit is the exhaustion of administrative

remedies. Civil Rights Act of 1964,

GRIFFIN v. CARLIN 2769

§ 717(c), as amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-

16(c).

11. Civil Rights ®=32(1)

Inasmuch as the confusing Civil Ser

vice Commission regulations in existence in

1971 provided no clear means by which

class action claims could be raised at the

administrative level and that the adminis

trative complaint filed by the Postal Ser

vice employee satisfied the purpose of the

administrative exhaustion requirement, em

ployee’s third-party complaint satisfied re

quirement of exhaustion of administrative

remedies and could serve as the basis for

Title VII class action suit. Civil Rights Act

of 1964, § 717(c), as amended, 42 U.S.C.A.

§ 2000e-16(c).

12. Federal Civil Procedure <3= 162

Federal Courts <£=>317

Questions concerning class certifica

tion are left to sound discretion of district

court; assuming district court's determina

tion is made within parameters of class

action rule, its decision on class certifica

tion will be upheld absent an abuse of

discretion. Fed.Rules Civ.Proc.Rule 23, 23

U.S.C.A.

13. Federal Civil Procedure <£=134.10

Named plaintiffs raised claims within

periphery of claims raised by one plaintiff’s

administrative complaint and therefore

were proper named plaintiffs and the

claims raised by those 22 plaintiffs satis

fied the commonality and typicality require

ments of class action rule and those plain

tiffs also satistied adequacy of representa

tion requirement; thus, district court did

not abuse its discretion in certifying class

consisting of all past, present, and future

black employees of certain post office in

Title ’VII suit alleging discrimination in pro

motions. Fed.Rules Civ.Proc.Rule 23(a), 28

U.S.C.A.; Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 701 et

seq., as amended. 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e et

seq.

14. Civil Rights <t=38

Only issues that may be raised in a

Title VII class action suit are those issues

that were raised by representative parties

in their administrative complaints, together

with those issues that may reasonably be

expected to grow out of the administrative

investigation of their claims. Civil Rights

Act of 1964, § 701 et seq., as amended, 42

U.S.C.A. § 2000e et seq.

15. Federal Civil Procedure C=1S4.10

In a Title VII suit, it is not necessary

that members of the class bring an admin

istrative charge as the prerequisite for join

ing as coplaintiffs in the litigation; it is

sufficient if they are in a class and assert

the same or some of the same issues. Civil

Rights Act of 1964, § 701 et seq., as

amended, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e et seq.

16. Federal Civil Procedure <S=164

Adequate representation requirement

of class action rule involves questions of

whether plaintiffs’ counsel are qualified,

experienced, and generally able to conduct

a proposed litigation, and whether plain

tiffs have interests antagonistic to those of

the rest of the class. Fed.Rules Civ.Proc.

Rule 23(a), 28 U.S.C.A.

Appeals from the United States District

Court for the Middle District of Florida.

Before KRAVITCH and JOHNSON, Cir

cuit Judges, and TUTTLE, Senior Circuit

Judge.

2770 GRIFFIN v. CARLIN

TUTTLE, Senior Circuit Judge:

Ernest Griffin and 21 other black em

ployees and former employees ' of the

United btates Postal service ac Jackson

ville, Florida, appeal from a decision of the

district court finding no classwide or indi

vidual discrimination under Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-16. Appellants contend

that tne district court erred in excluding

their challenge to written tests used in the

promotion process, in excluding all dispar

ate impact claims, and in finding no dispar

ate treatment in promotions, awards, disci

pline, and details. On cross-appeal, the

Postal Service argues that the district

court erred in allowing a third-party com

plaint to serve as the administrative basis

for this suit and in certifying this suit as a

class action.

On August 29, 1971, Griffin filed with

the United States Civil Service Commission

a complaint under the third-party compiaint

procedure authorized by then-current regu

lations of the Commission and of the Postal

Service. 5 C.F.R. § 713.204(d)(6) (1971); 39

C.F.R. § 747.5(a) (1971). The compiaint

stated:

Please accept this letter as a third par

ty discrimination complaint against Post

master J.E. Workman of the Jackson

ville, Florida Post Office. This discrimi

natory complaint is based on race since

qualified blacks were and are still being

systematically excluded in training and 1

1. (1) D'Alver L. Wilson, Distribution Clerk; (2)

Charles C. .McRae, Clerk: (3) Richard Deloney,

Mailhandler; (4) Samuel George, Clerk: (3) Al-

phonso West, Clerk; (6) Erno Denefield. Mail-

handler; (7) Thaddeus E. Raysor, Clerk; (S)

Margie L. Raysor, Distribution Clerk: (9) Joe

Bailey, Jr., Clerk: (10) Andrew Edwards, Carri

er; (11) Claude L. Smith, Clerk Technician; (12)

development and opportunities for ad

vancements.

The Postal Service investigated the com

plaint and found no discrimination.

On July 7, 1972, plaintiffs filed a class

action suit in federal district court chal

lenging defendant's use of discriminatory

assignment and promotion methods and

other discriminatory employment practices.

On January 9, 1973, the district court en

tered an order authorizing plaintiffs to pro

ceed as representatives of a class and dis

missing that portion of the plaintiffs’ com

plaint which challenged the use of written

tests in the promotion process. The dis

missal was based on the court’s finding

that plaintiffs had failed to exhaust admin

istrative remedies as to the testing issue.

In 1976, plaintiff Griffin was fired from

the Postal Service. He appealed the dis

charge under the then-existing regulatory

scheme to the United States Civil Service

Commission. In that appeal, he raised the

claim that he had been discriminated

against because of his race and that the

action was part of a pattern and practice of

racial discrimination and reprisal against

those persons challenging discrimination.

Griffin timely filed a supplemental com

plaint in the present action raising .those

claims. On the district court's order, a

consolidated amended complaint was filed

on November 12, 1981. This complaint

again alleged discrimination against blacks

in defendant s assignment and promotion

methods and other employment practices.

Smith M. Morgan. Clerk Technician; (13) Jesse

L. Wilcox. Clerk; (14) Harvev J. Harper, Clerk-

da) Joyce A. Scales, Clerk; (16) Albert Jackson.

Jr., Mailhandler; (17) Kenneth A. Rosier, Distri-

uiition Clerk; (18) Andrew D. Martin, Jr., Clerk;

(19) James Williams, Clerk; (20) John H. Fowl

er, Mechanic; (21) Dons D. Galvin, Relief Win

dow Clerk.

GRIFFIN v. CARLIN 2771

On September 8, 1982. the district court

dismissed plaintiffs’ disparate impact

claims on the grounds that plaintiffs’ plead

ings had failed to put defendants on notice

as to which employment practices would be

challenged on this theory and that only

objective, facially neutral employment prac

tices could be challenged on a disparate

impact theory. Thus, the case proceeded to

trial on a disparate treatment theory.

The Jacksonville Post Office employed an

average of 1,880 persons during the period

covered by this lawsuit. Approximately 32

percent of these employees were black.

The employees included clerks, mail han

dlers, city carriers, window clerks, and mo

tor vehicle operators.

The Jacksonville Post Office promotes

persons to supervisory positions almost en

tirely from within its work force. The pro

cess for promotion to initial supervisory-

positions has undergone some changes dur

ing the period covered by the lawsuit. In

1968, the Post Office used two written ex

aminations, one for vehicle services and

one for the post office branch. In order to

be placed on the supervisory register and

be eligible for promotion, employees had to

attain a particular score on the examina

tion. The top 15 percent of the employees

on the register were placed in the “zone of

c o n s i d e r a t i o n ’’ a n d w e r e n o t i f i e d o f s u p e r -

2 .

Year Pace Levels l —6 Levels 7 & Above H at 7 -

1969 Black 720 10 1 %

Other 1131 171 13%

1970 Black 711 12 2%

Other 1133 171 13%

1971 Black 666 11 2%

Other 1134 166 13%

1972 Black 647 11 2 %

Other 1063 166 13%

1973 Black 756 17 2%

Other 1230 162 12%

1974 Black 753 23 3%

Other 1221 177 13%

1975 Slack 744 27 4%

Other 1213 185 13%

visory vacancies. In 1972, the zone of con

sideration standard was eliminated and per

sons who had attained a passing score on

the examination were evaluated and graded

by- their supervisors. Those receiving an

“A” rating were eligible for immediate pro

motion. In 1976, the examination was elim

inated and employees were instead re

quired to complete a training program as a

precondition for promotion. In 1978, the

Postal Service initiated the Profile Assess

ment System for Supervisors (PASS) which

made eligibility for the supervisory regis

ters dependent on both supervisory assess

ment and self-assessment. No written ex

amination was used under the PASS pro

gram. Under all of these promotion sys

tems, promotion advisory boards inter

viewed and recommended eligible candi

dates for promotion, and the final selection

was made by the Postmaster.

Both plaintiffs and defendants relied

heavily on statistical data. Plaintiffs’ sta

tistics showed that blacks are far more

likely to noid jobs at level 4 or lower and

far less likely to hold jobs at or above level

7, the initial supervisor/ level.,2 According

to plaintiffs, the probabilities that the

grade distributions shown in their tables

would occur by chance are one in 10,000.

Plaintiffs' statistics showed that while 35

Year Race Levels 1-6 Lcveis 7 4 Above H a l 7*

1976 Black 723 23 4%

Other 1159 186 14%

1977 3lack 712 23 4% .

Other 1122 131 14%

1973 3lack 702 43 6%

Other 1103 133 14%

1979 3lack 680 63 9%

Other 1106 227 17%

1980 3!ack 734 51 6%

Other 1189 195 14%

1981 Black 723 46 6%

Other 1225 185 13%

Source: Table 12. Plaintiffs' Exhibit ■*!.

GRIFFIN v. CARLIN

percent of the work force is biack, blacks

held only 5 percent of all supervisor/ jobs

in 1969 and only 21 percent in 1981. These

statistics also indicated that blacks were

promoted to supervisory positions in num

bers far lower than expected from 1964

through 1976. Plaintiffs contend that the

kev to the under-representation of blacks in

supervisory positions is their under-repre

sentation on the supervisory registers.

Their statistics indicated that the probabili

ties that the number of blacks on the regis

ters could have occurred by chance ranged

from 15 in one hundred trillion in 1968 to

67 in 100,000 in 1977.3

Plaintiffs’ statistics were based on the

use of the entire craft work force of the

Jacksonville Post Office as the applicant

pool for supervisory positions. The

government contends that the appropriate

pool is those individuals on the supervisory-

registers. Using this pool, the govern

ment’s statistics showed no evidence of

systemic discrimination against blacks

seeking supervisory positions.

Plaintiffs’ statistics showed a consistent

statistically significant over-disciplining of

3.

Craft Reij!isters Probability

Register White Black White Black

1968 1084 583 86 3 .1481 D-12’

1970 1070 580 123 16 .4160 D— 10

1973 1053 617 216 49 .1206 D-i 1

1974 1055 652 155 71 .1399 D-Ol

1975 982 627 220 34 .32-16 D-06

Mav '77 949 641 81 26 .2436 D-03

Dec. 77 949 641 39 32 .6700 D-03

1978 PM 933 611 14 5 .1708

Vab 933 611 16 9 .4413

CS 933 611 105 59 .1811

MP 933 611 116 93 .9492

*D-12 indicates that in the number to the left the decimal point

shouid be followed by 12 zeroes, and so on.

Source: Tabie 2. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit *1.

blacks in comparison to their numbers in

the relevant work force. Blacks, who con

stitute 35 percent of the work force, re

ceived between 52 and 67 percent of the

discipline.4 The government concedes that

blacks are disciplined more often than

whites, but argues that factors other than

race explain the disparity. Defendants’

statistics illustrated that black employees

at the Jacksonville Post Office are. on the

average, younger than white employees

and take more time off from work. The

Postal Service statistics also demonstrated

that, controlling for the number of previ

ous offenses, black employees did not re

ceive more severe punishment than white

employees.

In finding no discrimination, the district

court held that plaintiffs' statistical tables

had negligible probative value. This find

ing was based in part on the court’s deter

mination that plaintiffs’ expert had failed

to control for relevant variables, such as

the fact that promotions were made only

from those on the supervisor/ registers.

In addition, the court noted that defendants

were able to point out errors in many of

4.

Incidences of Disciplinary Action by Race. Percentage of

Discipline and Year.

Year 3iack Other Total Probability

* % 4 %

1969 66 54% 57 46% 123 .001

1970 77 66% 39 34% 116 .COl

1971 63 65% 34 35% 97 001

1972 51 65% 23 35% 79 .001

1973 38 55% 31 45% 69 COl

1974 100 51% 98 49% 198 .001

1975 324 64% 182 36% 36 .001

1976 161 56% 124 44% 235 .001

1977 22 •67% 11 33% 33 .001

1973 204 53% 144 41% 348 .001

1979 154 55% 124 45% 278 .001

1980 178 52% 165 48% 343 001

1981 305 52% 235 48% 590 .001

Source: Table 9.1. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit *1.

GRIFFIN v. CARLIN 2773

plaintiffs tables, that many of plaintiffs’

tables provided no raw data, and that the

credibility of plaintiffs' expert was under

cut by his presentation at the last minute

of a substantially new statistical report.

The court found the report prepared by

defendant’s expert to be a reliable and

credible analysis of the promotion practices

at the Post Office. The court also found

that, based upon the government's statis

tics, it is likely that there were different

characteristics, patterns of conduct, or re

actions to circumstance which explain the

different levels of discipline.

Appellants introduced the testimony of

24 black class members to bring their sta

tistical evidence to life. The district court

concluded that appellants had not produced

a single witness who had demonstrated a

claim of discrimination. The court found

that many of plaintiffs’ witnesses were not

believable, that others were mistaken that

they were eligible for promotion, that oth

ers were not as qualified as the employee

selected, that some of the promotions chal

lenged had gone to black employees, and

that there were other non-discriminator/

reasons to explain the other alleged in

stances of discrimination. I.

I. DISMISSAL OF PLAINTIFFS'

■ CHALLENGE TO THE WRITTEN

TESTS

The district court's order of January 9,

1973, dismissed that portion of plaintiffs’

complaint challenging the use of written

tests as a condition of promotion. The

court noted that the requirement of ex

haustion of administrative remedies is sat

isfied when the issues .(a) are expressly

raised in the pleadings before the adminis

trative agency, (b) might reasonably be ex

pected to be considered in a diligent investi

gation of those expressly raised issues, or

(c) were in fact considered during the inves

tigation. The court held, however, that the

Postal Service had not had an opportunity

to consider the issue of the written test.

[1,2] The starting point for determin

ing the permissible scope of a judicial com

plaint is the administrative charge and in

vestigation. The judicial complaint is limit

ed to the scope of the administrative inves

tigation which could reasonably be expect

ed to grow out of the charge of discrimina

tion. . Evans v. L.S. Pipe & Foundry Co.,

696 F.2d 925, 929 (11th Cir.1983); Eastland

v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 714 F.2d

1066. 106< (11th Cir.1983), cert, denied sub

nom., James v. Tennessee Valley Authori

ty’ — U.S. -----, 104 S.Ct. 1415, 79

L.Ed.2d 741 (1984). Griffin’s administra

tive complaint charged racial discrimination

in that “qualified blacks were and are still

being systematically excluded in training

and development and opportunities for ad

vancements.” We hold that Griffin’s com

plaint clearly challenged aspects of defend

ant’s employment practices which would

reasonably include testing. The written

examinations were an integral part of the

promotional scheme from 1968 through

1976 because employees became eligible for

promotion to supervisory positions only by

attaining a passing score on the examina

tion. Thus, the impact of the written tests

should have been encompassed in a reason

able investigation of this charge of system

ic discrimination in promotions.

In fact, the investigative report prepared

by the Postal Service at the conclusion of

its investigation contains numerous refer

ences to the written tests. The report con

tains copies of both the 1968 and 1971

supervisory registers, and indicates that

only one black was in the zone of consider-

2774

GRIFFIN v. CARLIN

ation for promotion. The investigator’s re

port indicates that almost half or" the 31

black employees interviewed referred to

the- supervisory register or the written ex

amination. Several of these specifically in

dicated that they were ineligible for super

visory positions because they had failed the

written examination.

e find that the testing issue was or

should have been included in a reasonable

investigation of the administrative com

plaint. We therefore reverse the order of

the district court dismissing plaintiffs' chal

lenge to the written tests and remand for

consideration of that claim.

II. DISMISSAL OF DISPARAGE IM

PACT CLAIMS

[3] In the court below plaintiffs sought

to reiy on a disparate impact theory as well

as on a disparate treatment theorv. Plain

tiffs sought to apply the disparate impact

theory both to the final results of the mul

ti-component promotion process and to sev

eral component parts of that process, in-

c.udmg promotion advisory boards, awards,

A1" 6' In 'tS °rder of September S,’

the district court granted defendant's

motion to dismiss all claims by plaintiff

based on a disparate impact theory. The

court found that disparate impact analysis

is appropriate only to challenge objective,

facially neutral employment practices, and

not to challenge either the cumulative ef

fect of employment practices or subjective

decision-making. The court further found

that plaintiffs' pleadings had failed to put

deie.niants on notice as to which employ

ment practices would be challenged on a

disparate impact theory.

The district court relied on Pouncy v.

Prudential Insurance Company o f Amer

ica, 668 F.2d 795 (5th Cir 1982). and on

tirarns v■ Ford Motor Co., 651 F.2d 609

(8th Cir.1981). In Harris, the Eighth Cir

cuit neid that a subjective decision-making

system.cannot alone form the foundation

tor a disparate impact case. Id. at 611 In

Pouncy, the Fifth Circuit stated:

The discriminatory impact mode! of

proor in an employment discrimination

case is not, however, the appropriate ve

hicle from which to launch a wide rang

ing attack on the cumulative effect of a

company's employment practices

We require proof that a specific practice

results m a discriminatory impact on a

c.ass in an employer's work force in or

der to allocate fairly the parties' resoec-

tive burdens of proof at trial.. . . Identi

fication by the aggrieved partv of the '

specific employment practice responsible

for the disparate impact is necessary so

that the employer can respond by offer-

mg proof of its legitimacy.

Id. at 300-01.

, A recent Eleventh Circuit decision re-

ierrea to the Pouncy case and indicated

that use of the disparate impact model to

attack the excessive subjectivity 0f a per

sonnel system is “troublesome.” The court

stated, however:

Former Fifth Circuit precedent, how

ever, indicates that subjective selection

and promotion procedures may be at

tacked under the disparate impact theo-

7oq ^ Johnson v. Uncle Ben's, Inc.,

628 F._d 419, 426-27 (5th Cir.1980) va-

catea 451 U.S. 902. 101 S.Ct. 1967, 68

L.£d.2d 290 (1981), modified and a ffd

m part rev’d in part. 657 F.2d 750 (5th

tir.1981), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 967 103

S.Ct. 293, 74 L.Ed.2d 277 (1982).

^ o TenneSSee VaLley Authority,<04 F d 613, 619-20 (11th Cir.1983), cert,

denied suo nom., James v. Tennessee Val-

GRIFFIN v. CARLIN

ley Authority, — U.S. -----, 104 S.Ct.

1415. 79 L.Ed.2d 741 (1984). In Eastland.

the Court declined to decide whether the

prior Fifth Circuit case law was distin

guishable because the Court found that

plaintiffs had failed to prove discrimination

under the disparate impact theory.

In this case the issues of whether the

disparate impact model can be used to chal

lenge the final results of a multi-component

selection process and whether the disparate

impact model can be used to challenge sub

jective elements of a selection process are

squarely before us.' We find that we are

bound by former Fifth Circuit precedent to

allow disparate impact challenges to the

end result of multi-component selection

procedures and to subjective selection pro

cedures.5 6 Further, we hold that even if

these prior Fifth Circuit cases were not

binding, use of the disparate impact theory

to challenge the end result of multi-compo

nent selection processes and to challenge

subjective elements of those processes is

appropriate. We therefore reverse the or

der of the district court dismissing plain

tiffs’ disparate impact claims.

Several decisions of the former Fifth Cir

cuit, binding on this panel, applied a dispar

5. Fifth Circuit decisions prior to October 1.

1981, are binding in this Circuit and cannot be

overruled except by the court acting en banc.

Bonner v. Citv of Prichard, 661 F.2d 1206, 1207

(11th Cir.1981).

6. We note that while many subseo.uent Fifth

Circuit cases have followed Pouncy, see e.g.,

Carroll v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 70S F.2d 183,

138 (5th Cir. 1983) ("The use of subjective crite

ria to evaluate employees in hiring and job

placement decisions is not within the category

of facially neutral procedures to which the dis

parate impact modei is applied."), at least one

posi-Pouncy Fifth Circuit decision has applied

disparate impact analysis to a subjective promo

tional system. Page v. U.S. Industries, Inc., 726

F.2d 1038 (5th Cir.1984). In Page, the Court

noted the Pouncy decision but stated:

ate impact analysis to the end result of

multi-component selection processes con

taining subjective elements. For example,

in Johnson v. Uncle Ben's, Inc., 628 F.2d

419, 426-27 (oth Cir. 1980), vacated, 451

U.S. 902, 101 S.Ct 1967, 68 L.Ed.2d 290

(1981), modified and affid in part, rev'd

in part, 657 F.2d 750 (5th Cir. 1981), cert,

denied. 459 U.S. 967, 103 S.Ct. 293, 74

L.Ed.2d 277 (1982), the court applied a dis

parate impact analysis to a promotion sys

tem based on the use of subjective supervi

sory evaluations. See also, •Crawford v.

Western Electric Co., Inc., 614 F.2d 1300,

1318 (5th Cir.1980) (applying disparate im

pact analysis to index review system in

volving subjective elements); Rowe v. Gen

eral Motors Corp.. 457 F.2d 348, 354-55

(5th Cir.1972) (applying disparate impact

analysis to promotion system involving

foreman’s recommendations).

Even if we were not bound by these

decisions to allow application of disparate

impact analysis to the end result of a multi-

component promotion process and to pro

cesses involving subjective elements, we

would still be inclined not to follow the

decision of the current Fifth Circuit in

Pouncy.* The Supreme Court first articu-

It is clear that a promotional system which

is based upon subjective seiection criteria is

not discriminatory per se. Consequently,

such a system can be facially neutral but vet

be discriminatorily applied so that it impacts

adversely on one group. In using a disparate

impact analysis, the district court pointed out

that many of this Court's decisions examine

the classwide impact of a subjective promo

tional system. See. e.g„ dames v. Slockham

Valves di Fittings Co., 559 F.2d 310 (5th Cir.

1977), cert, dented. 434 U.S. 1034, 98 S.Ct. 767,

54 L.Ed.2d 731 (1973); Ro-.ve v. General .'do-

tors Corp.. 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir.1972). We

agree with the district court’s assessment that

the subjective promotional system in this case

indeed may have had a classwide impact.

Thus, we examine the defendant's promotion-

GRIFFIN v. CARLIN

laced the disparate impact model of discrim

ination, under which proof of discriminato

ry intent is not necessary, in Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.3. 424, 91 S.Ct.

849, 28 L.Ed.2d 158 (1971), In Gnggs, the

Court indicated that Tide VII requires “the

removal of artificial, arbitrary, and unnec

essary barriers to employment” which “op

erate as built-in headwinds' for minority

groups and are unrelated to measuring job

capability.” Id. at 431-32, 91 S.Ct. at 853-

54. The Court in Gnggs did not differenti

ate between objective and subjective barri

ers, and, in tact, the Court made frequent

rerere.nces to “practices” and “proce

dures,” terms that clearly encompass more

than isolated, objective components of the

overall process.7

In the recent case of Connecticut v.

Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 102 S.Ct. 2525, 73

L.Ed.2d 130 (1982), the Supreme Court held

that the “bottom line" result of a promo

tional process could not be used as a de

fense to a disparate impact challenge to a

particular selection procedure used in that

promotion process. The Court emphasised

the holding in Gnggs that Title VII re

quires the elimination of “artificial, arbi

trary, and unnecessary barriers to employ

ment,” and again did not differentiate be

tween objective and subjective criteria nor

give any indication that a disparate impact

challenge could not be made to a promo

tional system as a whole. See 457 U.S. at

448-452, 102 S.Ct. at 2532-2534. The

Court noted the legislative historv of the

1972 amendments to Title VII, 86 Scat.

al system under the disparate impact model

as well.

Id. at 1046. We note also the recent decision of

the D.C. Circuit in Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d

1249, 1288 n. 34 (D.C.Cir.1984) ('Though these

practices arguably encompass some subjective

judgments as to agents performance, we find

103-113, which extended Title VII to feder

al government employees. The Court

pointed out that Congress recognized and

endorsed the disparate impact analysis em

ployed in̂ Griggs. The Court specifically

cited the Senate Report (S.Rep. No. 92-415_,

p. 5 (1971)), which stated:

Employment discrimination as viewed

.oday is a . . . complex and pervasive

phenomenon. Experts familiar with the

subject now generally describe the prob

lem in terms of 'systems’ and ‘effects’

lather than simpiv intentional wrongs.

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 447 n. 8,

102 S.Ct. 2525, 2531 n. 8, 73 L.Ed.2d 130.

The dissenters in Teal, while disagreeing

with the Court’s conclusion that the bottom

line could not be used as a defense, clearly

indicated their understanding that dispar

ate impact challenges could be made to the

t.otai selection process. The dissenters

stated that “our disparate-impact cases

consistently have considered whether the

result of an employer's total selection pro

cess had an adverse impact upon the pro

tected group.” Id. at 458, 102 S.Ct. at 2537

(Powell, J„ dissenting) (emphasis in origi

nal).

We have repeatedly held that subjective

practices such as interviews and supervi

sor}' recommendations are capable of oper

ating as barriers to minority advancement.

See. e.g.. Johnson, 628 F.2d" at 426; Rowe

457 F.2d at 359; Miles v. M.N.C. Corp., 750

F.2d 367, 871 (11th Cir. Jan. 13, 1985).

exclusion of such subjective practices from

the reach of the disparate impact model of

that disparate impact appropriately applies to

them.')

7. Eg., 401 U.S. at 430, 91 S.Ct. at S33 ("prac

tices, procedures, or tests'-); id. at 431, 91 S.Ct.

at 853 ("practices'-); id at 432, 9! S.Ct. at 354

("employment procedures or testing mecha

nisms ); id ("any given requirement”).

GRIFFIN v. CARLIN

analysis is likely to encourage employers to

use subjective, rather than objective, selec

tion criteria. Rather than validate educa

tion and other objective criteria, employers

could simply take such criteria into account

in subjective interviews or review panel

decisions. It could not have been the in

tent of Congress to provide employers with

an incentive to use such devices rather

than validated objective criteria.

Likewise, limiting the disparate impact

model to situations in which a single com

ponent of the process results in an adverse

impact completely exempts the situation in

which an adverse impact is caused by the

interaction of two or more components.

This problem was recognized in the recent

Eighth Circuit decision in Gilbert v. City of

Little Rock, Ark.. 722 F.2d 1390 (8th Cir.

1983), cert, denied, — U.S.----- , 104 S.Ct.

2347, 80 L.Ed.2d 820 (1984). The Court

there held that the district court's finding

of no discrimination under a disparate im

pact theory was incorrect because “the dis

trict court neglected to adequately consider

the interrelationship of the component fac

tors and, more specifically, whether the

oral interview and performance appraisal

factors . . . had a disparate im pact....”

Id. at 1397-98.

Finally, we note that the Uniform Guide

lines on Employee Selection Procedures. 29

C.F.R. § 1607, developed by the four feder

al agencies with responsibility for enforc

ing Title VII, interpret the disparate impact

model to apply to all selection procedures,

whether objective or subjective. The

Guidelines define the selection procedures

to which a disparate impact analysis applies

as follows:

Any measure, combination of meas

ures, or procedure used as a basis for

any employment decision. Selection pro

cedures include the full range of assess

ment techniques from traditional paper

and pencil tests, performance tests, train

ing programs, or probationary periods

and physical, educational, and work expe

rience requirements through informal or

casual interviews and unscored applica

tion forms.

29 C.F.R. § 1607.16(0.).

We therefore reverse the.order of the

district court dismissing plaintiffs’ dispar

ate impact claims and remand to that Court

for consideration of the plaintiffs' disparate

impact challenges to the final result of the

defendants’ overall promotion process and

to specific components of that process

whether subjective or objective.

III. DISPARATE TREATMENT IN

PROMOTIONS, DETAILS, DISCI

PLINE, AND AWARDS

After the district court eliminated plain

tiffs’ disparate impact claims, plaintiffs

proceeded to trial on a disparate treatment

theory. After consideration of plaintiffs’

statistical and anecdotal evidence, the dis

trict court held that plaintiffs had failed to

prove any class-wide discrimination.

[4,5] In a disparate treatment case

proof of discriminatory motive or intent is

essential. International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324,

335-36 n. 15, 97 S.Ct 1843, 1854-55 n. 15,

52 L.Ed.2d 396 (1977). In an action alleg

ing class-wide discrimination plaintiffs

must “establish by a preponderance of the

evidence that racial discrimination was the

company's standard operating procedure—

the regular rather than the unusual prac

tice.” Id. at 336, 97 S.Ct at 1855. A

prima facie case of disparate treatment

may be established by statistics alone if

277S GRIFFIN v. CARLIN

thev are sufficiently compelling. East-

land. 704 F.2d at 613 (11th Cir.1983). The

prima facie case is enhanced if the plaintiff

offers anecdotal evidence to bring "the cold

numbers convincingly to life." Teamsters,

431 U.S. at 339, 97 S.Ct. at 1S56.

Once plaintiff establishes a prima facie

case of disparate treatment, the burden

shifts to defendant to rebut the inference

of discrimination by showing that plain

tiffs’ statistics are misleading or by

presenting legitimate non-discriminatory

reasons for the disparity. The defendant

does not have to persuade the court that it

was actually motivated by the proffered

reasons. It is sufficient if the defendant

raises a genuine issue of fact as to whether

it discriminated. Texas Department of

Community Affairs v. Burdine, 430 U.S.

248, 254, 101 s 'C t 10S9, 1094, 67 L.Ed.2d

207 (1981). If the defendant carries this

burden, the presumption raised by the pri

ma facie case is rebutted, and the plaintiff

must prove that the reasons offered by the

employer were pretextuai. Id. at 256, 101

S.Ct. at 1095.

[6] This Court may not reverse the deci

sion of the district court unless plaintiffs

establish that the court’s findings of fact,

whether of subsidiary or ultimate fact, are

dearly erroneous or that the court erred as

a matter of law. Pullman-Standard v.

Swint. 456 lT.S. 273. 2S5-90, 102 S.Ct 1781.

1788-91, 72 L.Ed.2d 66 (1982); Giles v.

Ireland, 742 F.2d 1366, 1374 (11th Cir.

1984). We now consider the court’s find

ings as to each of the four challenged

practices under this standard.

A. Promotions