Richmond v JA Croson Company Brief of Appellant

Public Court Documents

April 21, 1988

55 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Richmond v JA Croson Company Brief of Appellant, 1988. 495bf649-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/991575eb-1891-4777-ba66-ca41bb6b6106/richmond-v-ja-croson-company-brief-of-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

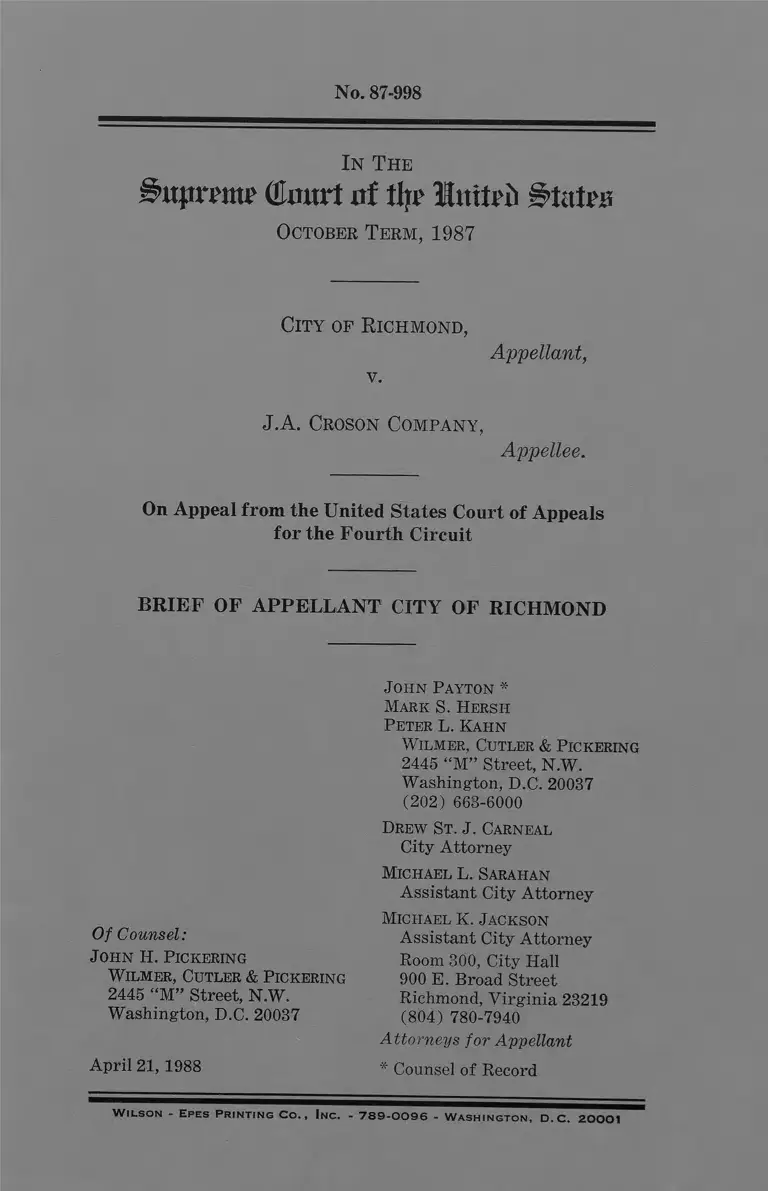

No. 87-998

I n T he

tikutrt of tlyr Huitei) States

October T e r m , 1987

Cit y of R ic h m o n d ,

v.

Appellant,

J.A . Croson Co m p a n y ,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF APPELLANT CITY OF RICHMOND

Of Counsel:

John H. Pickering

Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering

2445 “M” Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037

April 21,1988

John Payton *

Mark S. Hersh

Peter L. Kahn

Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering

2445 “ M” Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037

(202) 663-6000

Drew St . J. Carneal

City Attorney

Michael L. Sarahan

Assistant City Attorney

Michael K. Jackson

Assistant City Attorney

Room 300, City Hall

900 E. Broad Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

(804) 780-7940

Attorneys for Appellant

* Counsel of Record

W i l s o n Ep e s P r i n t i n g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 -0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , D .C . 20001

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether a city, in order to remedy the virtual ab

sence of minority participation in its city construction

contracts caused by racial discrimination in its construc

tion industry, may enact an ordinance that requires prime

construction contractors to subcontract a portion of their

city contracts to minority businesses.

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

OPINIONS BELOW ............................................................ 1

JURISDICTION................... ......... ......................... ................ 2

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION AND ORDI

NANCE INVOLVED ........................................................ 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .... ................................. 3

A. Enactment Of The Minority Business Utiliza

tion Ordinance ......................................... 3

B. The Ordinance’s Provisions_______ _____ 7

C. The Ordinance Applied To Croson ........... ........... 9

D. The Proceedings Below ................ ............ ....... ....... 10

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............................................ 14

ARGUMENT................. 17

I. RICHMOND HAS A COMPELLING INTER

EST IN REMEDYING THE EFFECTS ON

ITS PUBLIC WORKS PROGRAM OF RACIAL

DISCRIMINATION IN THE LOCAL CON

STRUCTION INDUSTRY ___ 19

A. Racial Discrimination In The Local Con

struction Industry Had Substantially Fore

closed Minority Access To City Contracting

Opportunities ................... 20

B. Like Congress, Richmond Had A Compelling

Interest In Remedying The Effects Of Iden

tified Discrimination On Its Own Public

Works Program .......................... ......................... 28

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... v

(iii)

IV

C. Richmond’s Remedial Action Is Justified

Without Evidence Of Its Own Discrimina

tion ............. 33

D. Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education Does

Not Control This Case ...................................... 38

II. THE RICHMOND ORDINANCE IS SUFFI

CIENTLY NARROWLY TAILORED TO

ACHIEVE ITS REMEDIAL PURPOSE............. 41

A. The Richmond Ordinance Is Necessary To

Remedy The Effects Of Racial Discrimina

tion On City Construction Contracting And

Has Minimal Adverse Impact On Non-

Minorities ......... 42

B. The Ordinance Is Designed To Be Reason

able, Flexible And Temporary........................ 45

CONCLUSION .................... 47

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

Page

Cases Page

American Textile Manufacturer’s Institute v.

Donovan, 452 U.S. 490 (1981) .... .................. ...... 27

Board of Directors of Rotary International v.

Rotary Chib of Duarte, 107 S. Ct. 1940 (1987).. 29

Bradley v. School Board, 462 F.2d 1058 (4th Cir.

1972) (en banc) aff’d by an equally divided

Court, 412 U.S. 92 (1973) (per curiam)............. 26

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) ........... ........... ............. ............................... ....... 18

City of Renton v. Playtime Theatres, Inc., 475

U.S. 41 (1986)...... ..................... .............................. . 26

City of Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358

(1975) ................................................. .................... 26

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977)....... 34

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980)____passim

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977)___ ____ _______ ....21, 27, 46

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clara

County, 107 S. Ct. 1442 (1987) .............passim

Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers’ International

Association v. EEOC, 478 U.S. 421, 106 S. Ct.

3019 (1986)................. .......... ....... ...................18,19,38,43

Members of City Council v. Taxpayers for Vin

cent, 466 U.S. 789 (1984)____ _______ __________ 30

Memphis Light, Gas & Water Division v. Craft,

436 U.S. 1 (1978) ............... ........................ ............ 7

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974).... 43

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88

(1945) ........................ ............................................... . 29

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978)................ ..............................passim

Rhode Island Chapter, Associated General Con

tractors of America v. Kreps, 450 F. Supp. 338

(D.R.I. 1978) ............................................. ......... ....... 24

Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609

(1984)..................................................j......... ....... ........ 29

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976) ........ 31

Schmidt v. Oakland Unified School District, 662

F.2d 550 (9th Cir. 1981), vacated on other

grounds, 457 U.S. 594 (1982)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

28

VI

Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36

(1872)..... ............................................................ .......... 37

South Florida Chapter of Associated General Con

tractors of America v. Metropolitan Dade

County, 723 F.2d 846 (11th Cir.), cert, denied,

469 U.S. 871 (1984) ............... ....................... .......... 11, 28

United States v. Paradise, 107 S. Ct. 1053 (1987) ..passim

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443

U.S. 193 (1979) ............. ....... ..... .....................24, 30, 34, 37

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, 476 U.S.

267 (1986) ........................................ .......... ........... passim

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes and Ordinances

U.S. Const, amend. X I V ................. ................................

28 U.S.C. § 1254(2) (1982)...........................................

42 U.S.C. § 1981 (1982).......................................... .

42 U.S.C. § 1983 (1982) .... ............... ...................... .

42 U.S.C. § 2000d (1982) ........................... ........... .

42 U.S.C. § 2000e (1982) ______ __ _________________

Va. Code Ann. § 11-44 (Repl. 1985)...........................

Minority Business Utilization Plan, codified at

Richmond, Va. Code ch. 24-1, art. 1(F) (Part

B) If 27.10-27.20, art. VIII-A (1983)...................

Regulations and Legislative Materials

41 C.F.R. § 60-4 (1987).................................... ....... ....... 35, 46

Notice, 45 Fed. Reg. 65979 (1980).............................. 35, 46

S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong. 1st Sess. 10 (1971).... 31

H.R. Rep. No. 1791, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 182

(1977) ......................................... .......... .....................6, 25, 27

Executive Orders

Exec. Order No. 11,114, 3 C.F.R. 774 (1959-63)

Exec. Order No. 11,246, 3 C.F.R. 339 (1964-65)

Exec. Order No. 12,086, 3 C.F.R. 230 (1979) .....

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Other Authorities

Days, Fullilove, 96 Yale L.J. 453 (1987)...... ........ . 24

J. Ely, Democracy and Distrust (1980).................. 18

6

6

6

2

2

10

10

10

30

31

2,7

vii

H. Hill, Black Labor and the American Legal Sys

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

tem: Race, Work, and the Law (1985) ............ 24

M. Karson & R. Radosh, “The AFL and the Negro

Worker, 1894-1949,” in The Negro and the

American Labor Movement (J. Jacobson ed.

1968) .................._........ ......................... ........................ 24

R. Marshall, “The Negro in Southern Unions,” in

The Negro and the American Labor Movement

(J. Jacobson ed, 1968) ................... ........ .......... . 24

G. Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro

Problem and Modem Democracy (1962).......... 24

Report of the National Advisory Commission on

Civil Disorders (1968) ................. ........... ........ ....... 32

R. Rowan & L. Rubin, Opening the Skilled Con

struction Trades to Blacks: A Study of the

Washington and Indianapolis Plans for Minority

Employment (1972) ...................................... .......... 24

S. Spero & A. Harris, The Black Worker: The

Negro and the Labor Movement (1931) ............. 24

Sullivan, Sins of Discrimination: Last Term’s

Affirmative Action Cases, 100 Harv. L. Rev. 78

(1986) .... ...................................... ................................ 34

L. Tribe, American Constitutional Law (2d ed.

1988) ........................... ....... ......................... ........... ...... 18

United States Bureau of the Census, May Report:

“Value of New Construction Put in Place”

(1986)................ 44

United States Bureau of the Census, PC(1)-B48,

General Population Characteristics, Virginia,

1970 Census of Population (1970) ...................... 46

IV United States Commission on Civil Rights, The

Federal Civil Rights Enforcement Effort— 1974

(1975).................... 32

United States Commission on Civil Rights, “Reve

nue Sharing Program— Minimum Civil Rights

Requirements” (1971) ....... 32

R. Weaver, Negro Labor: A National Problem

(1946)........................................ 24

I n T h e

iTtyUTMT (Cmtrt a t % Hutted B tatw

October T e r m , 1987

No. 87-998

C it y of R ic h m o n d ,

v Appellant,

J.A. Croson Co m p a n y ,

________ Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF APPELLANT CITY OF RICHMOND

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit from which this appeal is taken is

reported at 822 F.2d 1355 (4th Cir. 1987). It is repro

duced at page la in the appendices attached to the Juris

dictional Statement (“J.S. App. la ” ). The order of the

court of appeals denying the Petition for Rehearing with

Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc is unreported and is

reproduced at page 27a of the appendices attached to the

Jurisdictional Statement. An earlier opinion of the court

of appeals, which was vacated by this Court, is reported

at 779 F.2d 181 (4th Cir. 1985) and is reproduced at

page one of the supplemental appendices to the Jurisdic

tional Statement (“J.S. Supp. App. 1” ). The decision of

this Court granting certiorari, vacating the earlier judg

2

ment of the court of appeals and remanding to the court

of appeals is reported at 106 S. Ct. 3327 (1986) and is

reproduced at page 31a in the appendices attached to the

Jurisdictional Statement. The opinion of the district

court is unreported and is reproduced at page 112 of the

supplemental appendices to the Jurisdictional Statement.

JURISDICTION

The decision of the court of appeals declaring the Rich

mond ordinance unconstitutional and remanding to the

district court for determination of appropriate relief was

issued on July 9, 1987. J.S. App. la. A petition for re

hearing with suggestion for rehearing en banc, filed on

July 23, was denied on September 18, 1987, by a vote of

6-5. Id. at 27a. A notice of appeal to this Court was filed

with the court of appeals on November 18, 1987. Id. at

29a. This Court entered an order noting probable juris

diction in this case on February 22, 1988.

On March 7, 1988, the Clerk of this Court granted ap

pellant City of Richmond an extension of time for filing

its brief until April 21, 1988, pursuant to Rule 29.4 of

this Court. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. Section 1254(2) (1982).

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION AND

ORDINANCE INVOLVED

This appeal involves (1) the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution, which provides that no state shall “deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the Equal Protection of the

laws,” and (2) Richmond’s Minority Business Utilization

Plan, codified at Richmond, Va., Code ch. 24.1, art. 1(F)

(Part B) 1f 27.10-27.20, art. VIII-A (1983) . This plan is

reproduced at page 233 of the supplemental appendices to

the Jurisdictional Statement.

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case will decide the constitutionality of an ordi

nance enacted by appellant City of Richmond to remedy

the effects on its public works program of racial discrim

ination in its local construction industry. Before the en

actment of the ordinance, the Minority Business Utiliza

tion Plan, minority-owned businesses had been receiving

virtually none of Richmond’s public construction con

tracts even though the population of Richmond was half

minority. The ordinance requires recipients of city con

struction contracts to subcontract at least thirty percent

of the dollar amount of their contracts to qualified mi

nority-owned businesses.

Appellee J.A. Croson Co. ( “ Croson” ) is a non-minority

contractor that was denied a city construction contract

because it refused to comply with the ordinance’s sub

contracting requirement. The district court upheld the

ordinance but the court of appeals reversed, finding the

ordinance in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment.

A. Enactment Of The Minority Business Utilization

Ordinance

The Minority Business Utilization Plan was conceived

and enacted as a remedy for racial discrimination in

Richmond’s construction industry that had all but ex

cluded minority businesses from the City’s public works

program. Expressly designated “ remedial,” it promotes

wider participation by minority businesses in the City’s

construction projects. J.S. Supp. App. 248.

Prior to the ordinance, Richmond had been awarding

more than 99 percent of its construction business to

white-owned firms. Data compiled by the City’s Depart

ment of General Services in early 1983 indicated that in

the five previous years, two-thirds of one percent—essen

tially none— of the City’s $124 million in construction

contracts had been awarded to minority-owned busi

4

nesses.1 At that time, Richmond’s population was ap

proximately half minority, primarily black.2 3

The City’s elected leadership concluded that this de

plorable situation was a direct result of racial discrimina

tion in Richmond’s construction industry. On April 11,

1983, the Richmond City Council held a public hearing

and the merits of the proposed ordinance were vigorously

debated.® In addition to information about the negligible

minority participation in the City’s public construction

contracts, the City Council heard evidence that the major

construction trade associations in the Richmond area con

tained virtually no black members. The Associated Gen

eral Contractors of Virginia had 600 members, including

more than 130 in Richmond, but no black members ; 4 5 the

American Subcontractors Association had 80 members in

the Richmond area but no black members ; 6 the Richmond

chapter of the Professional Contractors Estimators As

sociation had 60 members but only one black member; 6

the Central Virginia Electrical Contractors Association

had 45 members but only one black member; 7 and the

Virginia Chapter of the National Electrical Contractors

1 Joint Appendix (“J.A.” ) 41. The data indicated that 0.67 per

cent of the value of the City’s construction contracts went to

minority-owned firms. See also J.S. Supp. App. 115.

2 J.A. 12, 29. The district court took judicial notice of the fact

that most minorities in Richmond were black. J.S. Supp. App. 207.

3 In its opinion below, the court of appeals stated that the debate

occurred “ at the very end of a five-hour council meeting.” J.S.

App. 6a. In fact, as appellee J.A. Croson Company stated in its

brief to the court of appeals, the debate lasted approximately one

hour and forty-five minutes. Brief of Appellant/Cross-Appellee at

23, J.A. Croson Co. v. City of Richmond, No. 85-1002 (L) No. 85-

1041 (4th Cir. Mar. 18, 1985).

4 J.A. 27-28.

5 Id. at 36.

« Id. at 39.

7 Id. at 40.

5

Association had 81 members but only two black mem

bers.8

Representatives of each of these trade organizations

appeared at the public hearing and spoke against the pro

posed ordinance. They claimed, among other things, that

there was an insufficient number of minority contractors

in the Richmond area to make the law work, and that

those available would be more expensive and less relia

ble.9 Supporters of the ordinance replied that similar

arguments had long been used to limit minority partici

pation in other endeavors, and often had proven un

justified.10 In Richmond’s own recent experience such

arguments had been made when the City began to ad

minister federal Community Development Block Grants,

which required minority participation in federally funded

construction and other projects. Those arguments were

proven unfounded.11 12 One of the ordinance’s sponsors also

pointed out that the very purpose of the ordinance was

to provide opportunities for minority businesses to gain

experience and prove their capabilities.112

The existence of discrimination in Richmond’s con

struction industry—the core of the problem being ad

dressed-—was discussed at the public hearing and not dis

puted. One council member, a former Richmond mayor,

drew on his own long experience with the Richmond con

struction industry. He stated “without equivocation”

8 Id. at 34.

8 Id. at 31-32 (statement of Mr. Beck); id. at 33-34 (statement

of Mr. Singer); id. at 35-37 (statement of Mr. Murphy); id. at

38-39 (statement of Mr. Shuman).

10 Id. at 37 (statement of Mr. Kenney); id. at 43-44, 48 (state

ment of Mr. Richardson).

11 Id. at 41 (statement of Mr. Marsh). Mr. Marsh explained

that the percentage of minority participation in Community De

velopment Block Grants “exceeded the numbers specified and the

problems anticipated had not been realized.”

12 Id. at 43-44 (statement of Mr. Richardson).

6

that the industry is one in which “ race discrimination

and exclusion on the basis of race is widespread.” 18

Richmond’s City Manager, who has oversight responsi

bility for city procurement matters, concurred in these

remarks.13 14 No one denied that discrimination in the in

dustry was widespread,15 although some of the trade as

sociation representatives denied that their particular or

ganizations engaged in discrimination.16

The City Council also was aware that there has been

pervasive racial discrimination in the nation’s construc

tion industry. In 1977, the United States Congress had

enacted a federal set-aside plan for minority contractors

based on findings that the nation’s construction industry

is “ a business system which has traditionally excluded

measurable minority participation,” 17 18 and that industry

discrimination had severely limited minority participa

tion in public contracting at the federal, state and local

level.1® In Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980),

this Court upheld the constitutionality of the federal set-

aside plan, finding that Congress had “ abundant evi

13 Id. at 41 (statement of Mr. Marsh). Aside from his time in

public office in Richmond, Councilman Marsh has been practicing

law in Richmond since 1961.

14 Id. at 42 (statement of Mr. Deese).

15 J.S. Supp. App. 164-65.

16J.A. 20 (statement of Mr. Watts); id. at 39 (statement of

Mr. Shuman).

17H.R. Rep. No. 1791, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 182 (1977) (quoted

in Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448, 466 n.48 (1980) (plurality

opinion); id. at 505 (Powell, J., concurring).

18 Years earlier, the President of the United States had issued

an executive order authorizing affirmative action policies in federal

contract procurement as a means to remedy the effects of discrimi

nation. Exec. Order No. 11,114, 3 C.F.R. 774 (1959-63). This

program was continued with Exec. Order No. 11,246. See Exec.

Order No. 11,246, 3 C.F.R. 339 (1964-65) as amended by Exec.

Order No. 12,086, 3 C.F.R. 230 (1979).

7

dence” of racial discrimination in the construction indus

try to support its remedial action. Id. at 477-78 (plural

ity opinion). The Richmond ordinance was drafted with

the Fullilove decision, and the findings of discrimination

discussed therein, in mind. J.A. 14-15, 24-25.

At the end of the public hearing, the City Council

voted six to two, with one abstention, to enact into law

the Minority Business Utilization Plan.10

B. The Ordinance’s Provisions

The Minority Business Utilization Plan requires con

tractors to whom the City awards prime contracts to

subcontract at least thirty percent of the dollar amount

of the contracts to minority business enterprises (MBEs),

unless the prime contractor is itself an MBE or the City

waives the requirement. The ordinance is designed to

expire on June 30, 1988.®?

Because the ordinance does not set aside prime con

tracts for minority businesses, the competitiveness of the

bidding process is preserved. Since a prime contractor

normally must make subcontracting arrangements before

it can calculate its bid, the ordinance contemplates that

minority subcontractors will be participants in the com

petitive bidding process. Once the bids are opened, the

apparent low bidder is given ten days to submit a satis

factory Minority Business Utilization Commitment Form,

containing information about the MBE subcontractor or 19 20

19 Richmond, Va. Code ch. 24.1, art. 1(F) (Part B) If 27.10-27.20

(1983). The plan actually was enacted pursuant to two ordinances.

See J.S. Supp. App. 233, 249.

20 Of course, the expiration of the Minority Business Utilization

Plan does not moot this case. There remains a live controversy

between the parties over whether Richmond’s refusal to award

Croson a contract was unlawful and entitles Croson to damages.

Memphis Light, Gas & Water Div. v. Craft, 436 U.S. 1, 8-9 (1978).

8

subcontractors, or to seek a waiver of the minority sub

contracting requirement. J.S. Supp. App. 60-61, 69.21

The ordinance authorizes the Director of the Depart

ment of General Services to promulgate regulations

“which . . . shall allow waivers in those individual situa

tions where a contractor can prove to the satisfaction of

the director that the requirements herein cannot be

achieved.” 22 According to these regulations, the thirty

percent requirement will be waived or lowered in the fol

lowing circumstance:

To justify a waiver, it must be shown that every

feasible attempt has been made to comply, and it

must be demonstrated that sufficient, relevant, quali

fied Minority Business Enterprises (which can per

form subcontracts or furnish supplies specified in

the contract bid) are unavailable or are unwilling

to participate in the contract to enable meeting the

30% MBE Goal.

Id. at 67-68. The denial of a waiver may be appealed

under the City’s normal appeals procedures for disap

pointed bidders. Id. at 192.

The ordinance defines a Minority Business Enterprise

as a business at least fifty-one percent of which is owned

and controlled by minority group members.23 The ordi

21 Since the time that Croson brought this lawsuit, that procedure

has been changed. The new requirement is that a prime contractor

must submit a Minority Business Utilization Form or a waiver

request with its bid or the bid will be considered non-responsive.

22 J-S. Supp. App. 247. The City Council contemplated that the

regulations would be similar to the waiver provisions used in the

City’s administration of Community Development Block Grants.

J.A. 12-13.

28 J.S. Supp. App. 251. The requirement that the business be

controlled as well as owned by minority group members was added

by amendment to the plan in June 1983. See id. at 217-18. Minority

group members are defined as “ [c]itizens of the United States who

are Blacks, Spanish-speaking, Orientals, Indians, Eskimos, or

Aleuts.” Id. at 252.

9

nance’s regulations require a city administrative officer

to verify that minority businesses seeking to participate

in a city construction contract are in fact owned and

controlled by minorities, so that “ sham” MBEs cannot

take advantage of the plan. Id. at 62. The regulations

also list the names and phone numbers of five Richmond

agencies that will assist contractors in locating qualified,

bona fide minority businesses to participate in a con

struction contract. Id. at 67.

C. The Ordinance Applied To Croson

On September 6, 1983, Richmond invited bids for the

installation of plumbing fixtures at the city jail. The bids

were due by October 12. J.S. Supp. App. 120. Croson, a

non-MBE mechanical, plumbing, and heating contractor

based in Richmond, decided to bid on the project and de

termined that it could meet the City’s minority subcon

tracting requirement by purchasing certain plumbing

fixtures from an MBE. Id. at 121.

Croson’s regional manager, Eugene Bonn, had brief

telephone conversations with several MBE suppliers on

September 30.24 On October 12, the day the bids were due,

he contacted a local MBE, Continental Metal Hose (“ Con

tinental” ).25 Continental’s president, Melvin Brown, told

Bonn that he wished to participate in the project with

Croson, but he could not state a firm price on such short

notice because he could not get an immediate commit

ment from suppliers. Id. at 122-23. Croson then sub

24 Evidence in the record indicates that Croson’s efforts to make

subcontracting arrangements with an MBE were less than diligent.

Telephone records submitted to the district court indicated that

the five conversations lasted a total of less than ten minutes. See

id. at 8 n.4. According to testimony before the district court, two of

these MBEs expressed interest in the project and requested bid

specifications from Bonn, but never received them. Officers of a

third testified that they never received Bonn’s call. Id.

25 Bonn claims to have telephoned Continental’s president on

September 30, but the president denies this. Id. at 121-22.

10

mitted a bid using a quote for the plumbing fixtures re

ceived from a non-minority firm. Id. at 124.

As it turned out, Croson was the only bidder and was

awarded the contract subject to its commitment to sub

contract with an MBE. Continental’s Brown attended

the bid opening on October 13 and at that meeting was

encouraged by Croson to continue trying to obtain a quote

from suppliers. Id. at 123-24. Croson nevertheless re

quested a waiver of the MBE requirement on October 19,

indicating simply that Continental was “unqualified” and

that other MBEs contacted were “ non-responsive” or “ un

able to quote.” Brown learned of the waiver request on

October 27, at which point he contacted a city official and

represented that Continental was available to provide the

fixtures specified in the contract. Id. at 124-25.

The City denied Croson’s request for a waiver by

letter dated November 2, and gave Croson ten more days

to comply with the subcontracting requirement. By that

time, Continental was able to quote a firm price, but it

was higher than Croson had hoped. Croson again re

quested a waiver, or, alternatively, an increase in the

contract price. The City elected instead to rebid the

project and invited Croson to submit another bid. Rather

than submit a new bid, Croson brought this lawsuit. Id.

at 126-29.

D. The Proceedings Below

In its complaint, Croson claimed that the Minority

Business Utilization Plan violated the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Virginia state

law, and it sought an injunction, declaratory relief, and

damages. After a bench trial, the district court held for

Richmond on all counts.26

26 Id. at 112. Croson also raised federal statutory claims based

on 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983 and Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d. However, Croson agreed these

claims had no basis in the absence of a valid equal protection claim,

J.S. Supp. App. 222-23, and did not raise them on appeal.

11

After finding the Richmond ordinance permissible un

der Virginia law, the district court considered Croson’s

equal protection claim. J.S. Supp. App. 155. Since the

appropriate constitutional standard for review of race-

based remedial programs had been left unresolved by this

Court in Fullilove and Regents of the University of Cali

fornia v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), the district court

relied on a three-part test synthesized from those cases

by the Eleventh Circuit:

(1) that the governmental body have the authority

to pass such legislation; (2) that adequate findings

have been made to ensure that the governmental body

is remedying the present effects of past discrimina

tion rather than advancing one racial or ethnic

group’s interest over another; (3) that the use of

such classifications extend no further than the estab

lished need of remedying the effects of past discrim

ination.27

The district court determined that the Richmond ordi

nance met all the requirements of this test, and thus

comported with the decisions of this Court in FvMLove

and Bakke.

_ The first element of the test was satisfied because Vir

ginia law granted municipalities the authority to adopt

such legislation. J.S. Supp. App. 162-63. The district

court found the second element satisfied because the City

Council had before it sufficient evidence to conclude that

racial discrimination in the local construction industry

had severely impaired minority participation in the in

dustry and that minority participation in the City’s own

public works program was negligible as a result. It cited

the “ enormous disparities” between the percentage of

city construction contracts awarded to minorities and the

27 J.S. Supp. App. 161-62 (quoting South Florida Chapter of

Associated Gen. Contractors of Am. v. Metropolitan Dade County,

723 F.2d 846, 851-52 (11th Cir.), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 871 (1984)

(emphasis omitted)).

12

percentage of minorities in Richmond, the hearing testi

mony of trade association representatives indicating that

there were few minority businesses in the local construc

tion industry, and the unrefuted hearing testimony about

discrimination in that industry. Id. at 164-65. It also

stated that Congress had “ already extensively documented

the fact that low levels of minority business participation

in the construction industry in general and government

contracting in particular reflect continuing effects of past

discrimination.” Id. at 165.

In considering the third element of the test, concern

ing the means employed in the remedial ordinance, the

district court relied on a five-factor inquiry derived from

Justice Powell’s Fullilove opinion: (1) the reasonableness

of the percentage chosen; (2) the adequacy of the waiver

provision; (3) the consideration of alternative remedies;

(4) the duration of the remedy; and (5) the ordinance’s

effects on innocent third parties. The court did a careful

analysis of each of these factors and concluded that the

test was satisfied. Id. at 172-98. It also rejected the argu

ment that the Richmond ordinance was “ overinclusive.”

Id. at 198-209.

On appeal, the court of appeals affirmed the district

court in all respects, with Judge Wilkinson dissenting. Id.

at 1. It found that the district court was correct to review

the Richmond ordinance under the equal protection stand

ards established in Fullilove, and that the district court

had appropriately applied those standards. Id. at 24-55.

Croson sought certiorari from this Court, which

granted the writ, summarily vacated the judgment, and

remanded the case for consideration in light of Wygant

v. Jackson Board of Education, 476 U.S. 267 (1986). On

remand, and without briefing or argument on the impact

of Wygant, the original panel of the court of appeals

reversed itself and found the Richmond ordinance un

constitutional, Judge Wilkinson writing for a divided

court over a dissent from Judge Sprouse. J.S. App. la.

13

As the court of appeals’ majority interpreted Wygant,

Richmond was required to demonstrate a “compelling”

interest in its ordinance, and could do that only by show

ing that it “had a firm basis for believing [there was]

prior discrimination by the locality itself.” Id. at 9a. The

majority considered the City’s statistical evidence “ spur

ious” and the City Council hearing testimony “nearly

weightless.” Id. at 8a. It concluded that the Richmond

ordinance was predicated only on “the loosest sort of

inferences” of past discrimination by the City, and there

fore was unconstitutional. Id. The majority also held, in

the alternative, that the ordinance was not sufficiently

“narrowly tailored” to meet its remedial goal. Id. at 11a.

The dissent argued that the majority “misconstrues and

misapplies Wygant,” Id. at 14a. It stated that Wygant

did not require evidence of discrimination in public pro

curement by the City itself, but that this requirement had

been satisfied in any event. Id. at 18a. It noted the history

of pervasive racial discrimination in the nation’s con

struction industry, id. at 19a, and it found that the dis

parity between the percentage of Richmond’s construction

contracts awarded to minority businesses and the per

centage of minorities in Richmond was so dramatic as to

“break [] the bounds of the sometimes suspect ‘science’

of statistics.” Id. at 21a.

The dissent concluded that the proof of governmental

discrimination required by the majority “might be fatally

counterproductive to the concept of affirmative action,” id.

at 20a, and in any event is inappropriate “ in areas where

discrimination had effectively prohibited the entry of

minorities into the contracting business, as in Richmond.”

Id. n .ll. It stated that the proof required by the majority

“would ensure the continuation of a systemic fait accom

pli, perpetuating a qualified minority contractor pool that

approximates two-thirds of one percent of the overall

contractor pool.” Id. at 20a. The dissent also found the

14

Richmond ordinance sufficiently narrowly tailored to pass

constitutional muster.

Richmond filed a petition for rehearing and suggestion

for rehearing en banc. The court of appeals denied the

petition by a vote of six to five. Id. at 27a.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The central issue in this case is whether the court of

appeals erred in holding Richmond’s Minority Business

Utilization Plan unconstitutional on the basis of language

in the plurality opinion in Wygant v. Jackson Board of

Education, which it construed to require a governmental

entity to demonstrate its own discrimination in order to

justify an affirmative action plan. To reach this conclu

sion, the court of appeals ignored relevant precedents of

this Court, particularly Fullilove v. Klutznick, which pre

sented facts and legal issues very close to those presented

here.

Upon analysis, it is clear that Wygant does not control

this case and that Richmond’s remedial ordinance is en

tirely consistent with the relevant precedents of this

Court. The ordinance represents a responsible legislative

effort to remedy the effects on the City’s public works

program of longstanding, pervasive racial discrimination

in the local construction industry. Richmond’s ordinance

is well designed to achieve its remedial purpose and has

only minimal impact on non-minorities.

In the five years prior to the enactment of the Minority

Business Utilization Plan in 1983, Richmond, which has

a population that is half minority, awarded more than

99 percent of its $124 million in public construction con

tracts to white-owned businesses. There is no serious dis

pute that this fact reflects a local construction industry

in which minority entry and advancement have been

stymied by years of racial discrimination. The effects of

this discrimination also are reflected in the virtual ab

sence of black members in Richmond’s major construction

15

trade associations. At the public hearing on the merits of

the ordinance, the City Council heard knowledgeable and

unrefuted testimony about this industry discrimination.

The City Council was well aware that Richmond was part

of a longstanding pattern of racial discrimination

throughout the nation’s construction industry.

Richmond had a compelling interest in remedying the

effects of this identified local industry discrimination on

its own public works program, much like the interest

supporting the federal program in Fullilove. Like Con

gress, the City had been awarding its taxpayers’ dollars

to a pool of contractors from which minorities had been

substantially excluded by unlawful racial discrimination,

and thus it had become a passive participant in that dis

crimination. Like Congress, Richmond sought to put

minority-owned construction firms on a more equitable

footing with respect to public contracting opportunities.

As this Court found in Fullilove, this was an entirely

appropriate use of affirmative action. Richmond needed

to take race into account because race-neutral remedies

would not overcome the disabling effects of past

discrimination.

Richmond’s interest in its ordinance was especially

compelling since if Richmond had not acted, there would

have been no remedy. Though part of a national pattern,

the effects of local construction industry discrimination

on Richmond’s own public works program was Rich

mond’s problem, peculiarly within the competence of

Richmond s legislative body. It would distort principles

of federalism to deny Richmond the means effectively to

address this problem, while permitting the federal gov

ernment to take similar remedial action under similar

circumstances.

The court of appeals below nevertheless held Rich

mond’s ordinance unconstitutional because it was not

predicated on Richmond’s own discrimination against

16

minority contractors. This requirement was based en

tirely on language in the plurality opinion in Wygant.

Not only did this language not receive the support of a

majority of this Court, hut even the plurality did not de

cide that a government always must demonstrate its own

discrimination in order to enact an affirmative action

plan. Governmental discrimination was not a decisive is

sue in Wygant, both because the evidence in the record

was not probative of any sort of discrimination, and be

cause layoffs were determined to be an inappropriate

means to achieve even a compelling purpose. Wygant

does not control the result here.

The court of appeals’ “governmental discrimination”

requirement is wholly inappropriate because pervasive,

unlawful industry discrimination, and its profound effect

on Richmond’s public works program, provided an ade

quate basis for remedial action. Requiring evidence of

governmental discrimination under these circumstances is

unnecessary and beside the point. Moreover, because proof

of governmental discrimination is elusive where industry

discrimination has largely prevented minority businesses

from even competing for city construction contracts, this

requirement would preclude any remedy for this most

effective and pernicious discrimination.

Finally, the minority business utilization ordinance is

carefully designed to meet its remedial goal with minimal

impact on non-minorities. By teaming up minority sub

contractors with more established, white-owned firms, the

ordinance removes obstacles that have kept minority

businesses out of public contracting and provides them

with valuable experience, credibility, and an opportunity

to develop business relationships with more established

firms. The ordinance’s impact on non-minorities is slight

since no prime contracts are set aside for minorities, the

subcontracting requirement does not unsettle any vested

right or expectation, and thirty percent of city construe-

17

tion contracts represents only a tiny fraction of all con

struction contracting opportunities in Richmond. In addi

tion, the ordinance is temporary, contains a reasonable

waiver provision, and is designed to root out “sham”

minority businesses.

ARGUMENT

Racial inequality remains a scourge of our society.

Cities, states, and the federal government each have a

crucial role to play in the effort to rid our country of

racial discrimination and its continuing effects.

Richmond, like other cities, has accepted that respon

sibility. In 1983, in response to clear evidence that ra

cial discrimination in its local construction industry had

resulted in a nearly all-white industry, and consequently

a distribution of public construction contracts only to

businesses owned by whites, Richmond enacted the Mi

nority Business Utilization Plan. This ordinance requires

contractors to whom the City awarded prime contracts

to subcontract at least thirty percent of the dollar amount

of their city contracts to minority businesses.

This case tests, whether the Constitution forbids Rich

mond from enacting this remedial legislation. More par

ticularly, it tests whether the court of appeals was cor

rect in relying on language in Wygant to the exclusion

of a line of more relevant precedents of this Court, es

pecially Fullilove. When the Richmond ordinance is ana

lyzed in light of its purpose and those precedents, it is

clear that it is constitutional and that the court of ap

peals’ reliance on Wygant was misplaced.

The level of constitutional scrutiny to be applied to

remedial legislation like the Richmond ordinance has not

been determined by this Court,2* Appellant submits that

[A] Ithough this Court has consistently held that some elevated

level of scrutiny is required when a racial or ethnic distinction is

18

an intermediate level of scrutiny, as endorsed by several

members of this Court, is the appropriate standard to be

applied in this case because racial classifications are not

inherently suspect where they are used as part of a rem

edy for the effects of identified racial discrimination.12® * 29

made for remedial purposes, it has yet to reach consensus on the

appropriate constitutional analysis.” United States v. Paradise,

107 S. Ct. 1053, 1064 (1987) (plurality opinion). See also id. n.17;

Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers’ Int’l Ass’n v. EEOC, 106 S. Ct.

3019, 3052-53 (1986) (plurality opinion) (“We have not agreed . . .

on the proper test to be applied in analyzing the constitutionality

of race-conscious remedial measures” ).

29 “ Government may take race into account when it acts not to

demean or insult any racial group, but to remedy disadvantages

cast on minorities by past racial prejudice. . . .” Bakke, 438 U.S.

at 325 (Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ., concurring

in the judgment in part and dissenting in part). See also Wygant,

476 U.S. at 296 (Marshall, J., dissenting); id. at 313 (Stevens, J.,

dissenting); Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 507 (Powell, J., concurring);

id. at 519 (Marshall, J., concurring in the judgment); id. at 550-

554 (Stevens, J., dissenting); Bakke, 438 U.S. at 305 (opinion of

Powell, J . ) ; id. at 359 (Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun

JJ., concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part).

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment does

not require strict scrutiny of affirmative action measures. Its core

purpose is not to prohibit the use of racial classifications per se, but

to prohibit their use to subjugate or disadvantage on the basis of

race. See Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 493-94 (1954)

(racial segregation in public schools violates the Equal Protection

Clause because it “ generates a feeling of inferiority” in the hearts

and minds of black children). See also J. Ely, Democracy and Dis

trust 135-36, 152-53 (1980); L. Tribe, American Constitutional Law

1514-21 (2d ed. 1988). Whites as a racial group historically have not

been subjugated or disadvantaged by non-whites, and affirmative

action does not have such a purpose or effect. Where, as here, it

appears that racial classifications are being used to remedy past

discrimination against non-whites, an intermediate level of judicial

scrutiny is sufficient to ensure that they are not actually serving

some improper purpose and that the effect that they have on whites

is not unreasonably burdensome.

19

Even under strict scrutiny, however, the Minority Busi

ness Utilization Plan passes constitutional muster.

Whatever the level of scrutiny, the constitutional in

quiry has two prongs: 1) whether the affirmative action

plan serves interests sufficiently “ important” or “ com

pelling” to justify the use of racial classifications; and

2) whether the plan is adequately tailored to serve its

purpose without unnecessarily harming the interests of

non-minorities.30 Richmond’s minority business utiliza

tion ordinance satisfies both of these requirements. It is

legislation designed to remedy the effects of identified

racial discrimination in Richmond’s construction industry

that substantially had foreclosed minority access to con

tracting opportunities with the City, and it is a tempor

ary, flexible plan that imposes little burden on non

minorities.

I. RICHMOND HAS A COMPELLING INTEREST IN

REMEDYING THE EFFECTS ON ITS PUBLIC

WORKS PROGRAM OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

IN THE LOCAL CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

State and local governments unquestionably have “a

legitimate and substantial interest in ameliorating, or

eliminating where feasible, the disabling effects of iden

tified discrimination.” 80 81 Richmond’s City Council adopted

its Minority Business Utilization Plan because racial

discrimination in Richmond’s construction industry long

had impaired minority entry and advancement in the in

dustry, and, as a consequence, minority businesses were

receiving virtually none of the City’s public construction

contracts. This factual predicate was found by the dis

trict court to be amply supported and has not seriously

been contested.

80 See Paradise, 107 S. Ct. at 1064 & n.17 (plurality opinion);

Sheet Metal Workers, 106 S. Ct. at 3052-53 (plurality opinion).

81 Bakke, 438 U.S. at 307 (opinion of Powell, J.).

20

Whether this predicate of discrimination justifies Rich

mond’s ordinance is the critical issue in this case. The

court of appeals held that the only predicate that would

justify the ordinance is the City’s own discrimination.

Richmond submits that it has a compelling interest in

remedying the effects of identified construction industry

discrimination on its public works program regardless of

whether the City itself has discriminated. Richmond’s

remedial action represents a considered decision by Rich

mond’s elected legislative body, which is fully aware of

its responsibilities to all the people of Richmond, and

constitutes an appropriate use of affirmative action.

A. Racial Discrimination In The Local Construction

Industry Had Substantially Foreclosed Minority

Access To City Contracting Opportunities

In 1983, one-half of the population of Richmond was

minority, primarily black. In the five years prior to 1983,

two-thirds of one percent—practically none— of the City’s

$124 million in construction contracts was awarded to mi

nority-owned businesses. As both the City Council and the

district court concluded, this disturbing fact was a direct

consequence of pervasive racial discrimination in Rich

mond’s local construction industry that had impaired

minority entry and advancement and had substantially

foreclosed minority opportunities to compete for city con

struction contracts.

This conclusion has abundant support in the facts of

this case. The disparity between the percentage of city

contracts awarded to minority businesses and the percent

age of minorities in Richmond— less than one percent ver

sus fifty percent— is so enormous that by itself it creates

a strong inference of discrimination. In a city that is half

minority and that awards $124 million in city construc

tion contracts over a five-year period, one would expect

21

minority businesses to be awarded much more than two-

thirds of one percent of those contracts, absent discrimi

nation.32 Because the number of minority contractors in

Richmond was “quite small,” J.S. App. 7a, this discrimi

nation must have been in the industry itself.

When this evidence is combined with other facts, the

inference of discrimination becomes so powerful that “ in

nocent” explanations of the meager minority participa

tion in Richmond’s city construction contracts seem far

fetched at best.33 As the City Council learned, and as

the following chart demonstrates, in 1983 there were lit

erally no black members in one of Richmond’s principal

construction trade associations, the Associated General

Contractors, and virtually no black members in other

major construction trade associations in the Richmond

area:

32 See International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324, 339-40 & n.20 (1977) (statistics showing racial im

balance between work force and general population may reflect dis

crimination).

33 The probativeness of the statistical evidence here is illustrated

by comparison to the statistical evidence of discrimination in Fulli-

love v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980). In enacting the minority

set-aside provision of the Public Works Employment Act of 1977,

Congress also relied on a disparity between the percentage of

federal contracts awarded to minority businesses and the percentage

of minorities in the general population. Id. at 459 (plurality

opinion). The level of minority participation in federal contracts

was also less than one percent, but minorities comprised only 15-18

percent of the nation’s population, compared to 50 percent in Rich

mond. Chief Justice Burger nevertheless cited this disparity as a

key piece of evidence in upholding Congress’ findings on the effects

of racial discrimination in the nation’s construction industry. Id. at

478 (plurality opinion).

22

BLACK MEMBERSHIP IN RICHMOND’S MAJOR

CONSTRUCTION TRADE ASSOCIATIONS IN 1983 34

Organization

Total

Membership

Black

Membership

Associated General

Contractors

(Virginia)

600 0

Associated General

Contractors

(Richmond)

130 0

American

Subcontractors

Association

(Richmond)

80 0

Professional

Contractors

Estimators

Association

(Richmond)

60 1

Central Virginia

Electrical

Contractors

Association

45 1

National

Electrical

Contractors

Association

(Virginia)

81 2

Like the negligible minority participation in the City’s

construction contracts, the near absence of minority mem

bers in these trade organizations is a manifestation of

pervasive racial discrimination in Richmond’s local con-

34 This chart lists those trade associations whose representatives

testified at the City Council hearing on the Minority Business

Utilization Plan and provided information on black membership.

J.A. 27-28, 34, 36, 39-40. The Richmond Builders Exchange, the

Richmond Plumbing, Heating and Cooling Contractors Association

and Richmond Area Municipal Contractors Association also were

represented at the hearing but provided no information on black

membership.

23

struction industry. Moreover, because membership in

these organizations represents a significant economic op

portunity;35 36 37 38 these figures dramatically underscore the

continuing effects of that discrimination.

At the City Council hearing, there was knowledgeable

testimony, including the testimony of a former Richmond

mayor, that discrimination in Richmond’s construction

industry in fact was widespread.®6 Moreover, while the

merits of the ordinance were vigorously debated, no one

denied that pervasive discrimination had occurred. It

simply was beyond dispute that discrimination had denied

minorities significant participation in the local construc

tion industry, and therefore in Richmond’s public con

struction contracts as well.37

Richmond’s experience is not unique. There is a long,

well-documented history of racial discrimination through

out the nation’s construction industry. Black workers for

years have been excluded from the skilled construction

trade unions and training programs and hired only for

relatively unskilled positions.88 Whites have dominated

35 For example, members of the Associated General Contractors

of America ( “AGC” ) perform almost 80 percent of all commercial

construction work in this country, according to a brief filed by the

AGC in the court of appeals below. See Motion of the Associated

General Contractors of America, Inc. for Leave to File as an

Amicus Curiae in Support of the Appellant/Cross-appellee at 3,

J.A. Croson Co. v. City of Richmond, Nos. 85-1002, 85-1041 (4th

Cir. Mar. 18, 1985). The AGC also points out that construction is

one of the largest industries in the United States, representing

approximately eight percent of the nation’s gross national product

Id.

36 See supra p. 5-6.

37 The record in this case contains no finding on the precise

number of contractors in Richmond who were minority in 1983,

though there has been no dispute that the number is “ quite small.”

J.S. App. 7a.

38 As this Court noted in a similar context, “ [j]udicial findings of

exclusion from crafts on racial grounds are so numerous as to make

24

the skilled construction trades, and blacks have been pre

vented from following the traditional path from laborer

to entrepreneur.®9 Consequently, most construction busi

nesses are owned and managed by whites, as in Rich

mond.* 40 Those few minority-owned construction busi

nesses that have been formed have faced formidable ob

such exclusion a proper subject for judicial notice.” United Steel

workers of Am. v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193, 198 n.l (1979).

This exclusion of black workers from skilled construction crafts

began over a hundred years ago. At the time of the Civil War,

black workers constituted the majority of the skilled workers,

including construction workers, in the South. H. Hill, Black Labor

and the American Legal System: Race, Work and the Law 9-11

(1985); S. Spero & A. Harris, The Black Worker: The Negro and

the Labor Movement 16 (1931); G. Myrdal, An American Dilemma:

The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy 1079-1124 (1962);

R. Weaver, Negro Labor: A National Problem 4-5 (1946); R.

Rowan & L. Rubin, Opening the Skilled Construction Trades to

Blacks: A Study of the Washington and Indianapolis Plans for

Minority Employment 10-15 (1972). After the Civil War, and

particularly after Reconstruction, black workers were systematically

evicted from their craft positions in favor of white workers and

barriers were erected to prevent black workers from entering those

crafts in the future. Hill, supra at 12-34, 235-47; Myrdal, supra at

228-29. Construction historically is an industry from which blacks

have been excluded by law and by the dominance of racially restric

tive unions. M. Karson & R. Radosh, “ The AFL and the Negro

Worker, 1894-1949,” in The Negro and the American Labor Move

ment 157-58 (J. Jacobson ed. 1968); Marshall, “ The Negro in

Southern Unions,” in The Negro and the American Labor Move

ment 145 (J. Jacobson ed. 1968).

99 Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 511-12 (Powell, J., concurring); Rhode

Island Chapter, Associated Gen. Contractors of Am. v. Kreps, 450

F. Supp. 338, 356 (D.R.I. 1978); Days, Fullilove, 96 Yale L.J. 453,

477 (1987).

40 J.S. App. 7a. According to testimony at the City Council hear

ing by a representative of the American Subcontractors Association,

the latest Bureau of Census figures indicated that 4.7 percent of

construction firms in this country are minority-owned, and 41 per

cent of these are concentrated in California, Illinois, New York,

Florida and Hawaii. J.A. 35.

25

stacles, rooted in discrimination, that have impaired their

ability to compete.41 As one report of the United States

House of Representatives stated, “ The very basic prob

lem . . . is that, over the years, there has developed a

business system which has traditionally excluded meas

urable minority participation.” 42 This discrimination has

as an inevitable corollary minimal participation by

minority-owned businesses in public construction con

tracting opportunities.

This history of racial discrimination in the construc

tion industry and its effects on public contracting are sig

nificant here because Richmond obviously has been part

of this national pattern. The drafters of Richmond’s

Minority Business Utilization Plan in fact consulted

this Court’s decision in Fullilove, which discussed findings

by the United States Congress that the effects of industry

discrimination have not been confined to federal contract

ing. J.S. Supp. App. 165. The Fullilove plurality stated:

“ [T]here was direct evidence before the Congress that

this pattern of disadvantage and discrimination existed

with respect to state and local construction contracting

as well.” 43 The congressional findings further support

41 In Fullilove, this Court explained some of the barriers that

minority businesses have faced in gaining access to government

contracting opportunities at the federal, state and local levels:

Among the major difficulties confronting minority businesses

were deficiencies in working capital, inability to meet bonding

requirements, disability caused by an inadequate ‘track record,’

lack of awareness of bidding opportunities, unfamiliarity with

bidding procedures, preselection before the formal advertising

process, and the exercise of discretion by government procure

ment officers to disfavor minority businesses.

448 TJ.S. at 467 (plurality opinion).

42 H.R. Rep. No. 1791, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 182 (1977) (quoted in

Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 466 n.48 (plurality opinion) and at 505

(Powell, J., concurring)).

4>3 448 U.S. at 478 (plurality opinion). This Court has held that

a city’s “substantial governmental interest” in regulating the time,

26

the conclusion that the enormous racial disparity in the

awarding of city construction contracts was a consequence

of racial discrimination in Richmond’s local construction

industry.44

The Richmond City Council, based upon the evidence of

discrimination outlined above and also upon its own

familiarity with the economic and social history of Rich

mond in general and the local construction industry in

particular 45 had abundant reason to conclude that racial

discrimination was responsible for the problem that it

faced. Its conclusion that discrimination had occurred is

unassailable. Richmond’s local construction industry

place, or manner of protected speech may be established by findings

and studies generated by other cities, “so long as whatever evidence

the city relies upon is reasonably believed to be relevant to the

problem that the city addresses.” City of Renton v. Playtime

Theatres, Inc., 475 U.S. 41, 51-52 (1986). It follows that Richmond

should be able to rely on findings relevant to its problem made by

the United States Congress and found by this Court to be supported

by direct evidence.

44 The facts supporting the Richmond ordinance are thus funda

mentally different from the statistical evidence found insufficient

to support the remedial plan in Wygant. In Wygant, the statistical

evidence was not probative of discrimination. See infra p. 39.

Here the extraordinary size of the disparity combines with other

facts to compel the conclusion that discrimination had occurred.

45 “ No race-conscious provision that purports to serve a remedial

purpose can be fairly assessed in a vacuum.” Wygant, 476 U.S.

at 296 (Marshall, J., dissenting). As this Court well knows, Rich

mond had confronted in its recent past the need to break down

racial barriers in various other segments o f its society and in the

city government itself. See, e.g., City of Richmond v. United States,

422 U.S. 358 (1975) (concerning the City’s annexation plan and

its compliance with the Voting Rights A c t ) ; Bradley v. School

Board, 462 F.2d 1058, 1065 (4th Cir. 1972) (en banc) (school

desegregation case, finding that “within the City of Richmond

there has been state . . . . action tending to perpetuate apartheid

of the races . . .” ), aff’d by an equally divided Court, 412 U.S. 92

(1973) (per curiam).

27

clearly has been “ a business system which has tradition

ally excluded measurable minority participation.” 46

Once Richmond established a basis for its remedial

action, the ultimate burden of proving the plan invalid

was on Croson. Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa

Clara County, 107 S. Ct. 1442, 1449 (1987); Wygant,

476 U.S. at 277-78 (plurality opinion). Croson did not

meet this burden. It could do nothing to rebut the com

pelling inference that racial discrimination was respon

sible for the “glaring absence” of construction contracts

awarded to minority contractors. International Brother

hood of Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 342, n.23 (“ [Fjine tuning

of the statistics could not have obscured the glaring

absence of minority line drivers . . . . [T]he company’s

inability to rebut the inference of discrimination came

not from a misuse of statistics but from ‘the inexorable

zero’ ” ) (quoted in Johnson, 107 S. Ct. at 1465 (O’Connor,

J., concurring in the judgment)). No other explanation

even would have been plausible.

The district court heard all the facts and agreed that

they supported an inference of discrimination. In a

thorough opinion, it explicitly found “ample evidence” to

conclude that the minimal minority participation in Rich

mond construction contracting reflected pervasive racial

discrimination in the local construction industry.47 The

48 Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 466 n.48 (quoting H.R. Rep. No. 1791,

94th Cong., 2d Sess. 182 (1977)).

47 J.S. Supp. App. 165-66, 172. A factual predicate for an af

firmative action plan properly is established when, after the plan

is challenged in court, the trial court finds “ a strong basis in

evidence” for the remedial action. Wygant, 476 U.S. at 277

(plurality opinion); see also id. at 286 (O’Connor, J., concurring

in part and concurring in the judgment) (contemporaneous finding

not required as long as there is “ firm basis for believing that

remedial action is required” ). Because the district court below

properly applied the “strong basis in evidence” test, its finding is

entitled to deference. Cf. American Textile Mfr’s Inst. v. Donovan,

452 U.S. 490, 529-30 (1981) ( “Whether or not in the first instance

we would find the Secretary’s conclusions supported by substantial

28

court of appeals did not question the conclusion that dis

crimination had occurred, holding instead that the Rich

mond plan was unconstitutional because there was no find

ing of discrimination by Richmond itself. J.S. App. at 9a.

Because the factual predicate for the Richmond ordinance

has more than adequate support in the record of this case,

the district court’s findings should not be disturbed on this

appeal.

B. Like Congress, Richmond Had A Compelling In

terest In Remedying The Effects Of Identified Dis

crimination On Its Own Public Works Program

The Minority Business Utilization Plan was enacted

after the City found itself doing business only with con

struction firms owned by whites, as a consequence of per

vasive racial discrimination in Richmond’s local construc

tion industry. The City had a compelling interest in end

ing this appalling state of affairs and creating opportu

nities in its own public works program that had been

unavailable to minorities due to that racial discrimination.

State and local governments48 unquestionably have a

compelling interest in remedying the effects of discrimina

tion and providing equal protection of the laws in their

evidence, we cannot say that the court of appeals in this case

‘misapprehended or grossly misapplied’ the substantial evidence

test” ).

48 A local government derives its powers from the state. The

manner in which a state chooses to delegate its powers to its

political subdivisions is a question of state law. Bakke, 438 U.S. at

366 n.42 (opinion of Brennan, J., White, J., Marshall, J. and

Blaekmun, J., concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting

in part); South Florida, Chapter of the Associated Gen. Contractors

of Am. v. Metropolitan Dade County, 723 F.2d at 852; Schmidt v.

Oakland Unified School Dist., 662 F.2d 550, 558 (9th Cir. 1981),

vacated on other grounds, 457 U.S. 594 (1982). The district court

found that the City Council had the authority under state law to

enact the Minority Business Utilization Plan. J.S. Supp. App. 141-

154. The court of appeals did not disturb this finding.

29

jurisdictions,49 This Court has held that this compelling

governmental interest extends to ensuring that publicly

available commercial opportunities are not denied to seg

ments of the population on the basis of race, gender, or

ethnic origin. See Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468

U.S. 609 (1984).50 In so holding, the Court stressed “the

importance, both to the individual and to society, of re

moving the barriers to economic advancement and political

and social integration that have historically plagued cer

tain disadvantaged groups . . . .” Id. at 626.

This case does not test the boundaries of this govern

mental interest, for at the very least a municipal govern

ment has a compelling interest in eradicating the effects

of discrimination and ensuring equal opportunity in its

own public works program. This interest is equivalent to 40

40 For example, in Railway Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88

(1945), this Court held that the states constitutionally could enact

legislation prohibiting discrimination by labor organizations.

80 In Roberts, this Court unanimously held that the Minnesota

Human Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination in places of

public accommodation, constitutionally could be applied to forbid

the Jaycees from excluding women from full membership. The

Court stressed that the exclusion of women from the Jaycees de

prived them of business contacts, employment promotions and other

commercial advantages that were publicly available to men. 468

U.S. at 626. The Court concluded that the state’s interest in break

ing down traditional barriers to opportunity was so compelling that

it justified some infringement on the Jaycee male members’ first

amendment rights of free association. Id. at 623-626. Justice

O’Connor, concurring, did not find an infringement of any rights

of association, but agreed with the Court that a compelling govern

mental interest was involved, She stressed the importance of “ the

power of States to pursue the profoundly important goal of ensur

ing nondiscriminatory access to commercial opportunities in our

society.” Id. at 632 (O’Connor, J., concurring in part and con

curring in the judgment). See also Board of Directors of Rotary

Int’l v. Rotary Club of Duarte, 107 S. Ct. 1940 (1987).

30

that which survived “ a most searching examination” by

this Court in Fullilove.51 Like Congress, Richmond deter

mined that minority businesses were receiving practically

none of its public construction contracting funds as a

result of racial discrimination in the construction indus

try. Like Congress, Richmond “has not sought to give

select minority groups a preferred standing in the con

struction industry, but has embarked on a remedial pro

gram to place them on a more equitable footing with

respect to public contracting opportunities.” 448 U.S. at

485-86 (plurality opinion). Ensuring nondiscriminatory

access to government contracting opportunities is, this

Court has stated, “ one aspect of the equal protection of

the laws.” Id. at 478 (plurality opinion).

Like Congress, the City needed to take race into account

in fashioning its remedy.52 Simply prohibiting discrimi

nation by its public contractors would have served little

purpose, since the discrimination was already unlawful.53 * * * * * * *

51 448 U.S. at 491 (plurality opinion). See also id. at 496

(Powell, J., concurring) (upholding the federal program “under

the most stringent level of review” ).

52 A local government’s action is not unconstitutional merely be

cause it has some negative impact on individuals’ constitutional

rights. See, e.g., Members of City Council v. Taxpayers for Vincent,

466 U.S. 789 (1984) (a city’s interest in advancing esthetic values

is sufficiently compelling to justify some curtailment of speech pro

tected by the first amendment).

53 Exclusion from a construction trade union on racial grounds

constitutes a violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e (1982). See United Steelworkers of America v.

Weber, 443 U.S. 193, 198 n.l (1979) (judicial findings under Title

VII of “exclusion from crafts on racial grounds are so numerous as

to make such exclusion a proper subject for judicial notice” ). Other

forms of employment discrimination in the construction industry

also violate Title VII, and employment discrimination by a recipient

31

Moreover, prohibiting future discrimination does nothing

to remedy the disabling effects of past discrimination. In

Richmond, years of purposeful racial discrimination in

the local construction industry had left white contractors

with overwhelming advantages in the competition for pub

lic construction contracts and the industry generally. The

negligible participation of minorities in the City’s con

struction contracts certainly gave no indication that this

state of affairs was going to change by itself any time

soon. Like Congress, the City determined that affirmative

action was necessary to create opportunities for minor

ity businesses in public contracting and help them be

come more competitive. Otherwise, the City faced the

likely prospect of continuing indefinitely to distribute its

taxpayers’ dollars to a pool of construction contractors

from which minorities had been effectively excluded.

The importance to Richmond of ensuring that govern

ment contracts are awarded without the taint of racial

discrimination cannot be overstated. Like discrimination

by the government itself, discrimination that forecloses

access to government benefits “creates mistrust, aliena

tion, and all too often hostility toward the entire process

of government.” * 64 The City, by continuing to award con

struction contracts to a pool of contractors from which

minorities had been practically excluded, in effect had be

come a passive participant in a system based on dis

crimination, and was helping to perpetuate that system.

There was great potential for mistrust of and hostility

toward the city government under these circumstances,

of a Virginia public contract violates Virginia law as well. Va. Code

Ann. § 11-44 (Repl. 1985). In addition, a white-owned construction

firm’s refusal on racial grounds to do business with a minority-

owned firm violates 42 U.S.C. § 1981 (1982), which prohibits dis

crimination in contracting. See Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U S 160

(1976).

64 Wygant, 476 at 290 (O’Connor, J., concurring) (quoting from

S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 10 (1971)).

and Richmond’s interest in taking remedial action was

substantial.

Furthermore, had Richmond not acted to remedy the

problem, there would have been no remedy. Though part

of a national pattern, the negligible minority participation

in Richmond’s public works program was Richmond’s

problem, to be addressed by Richmond. No other govern