Memorandum of Decision on the Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment

Public Court Documents

February 24, 1992

12 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Memorandum of Decision on the Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment, 1992. c860be98-a246-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/993d129c-bb3c-46b9-8b84-107d1d2314f5/memorandum-of-decision-on-the-defendants-motion-for-summary-judgment. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

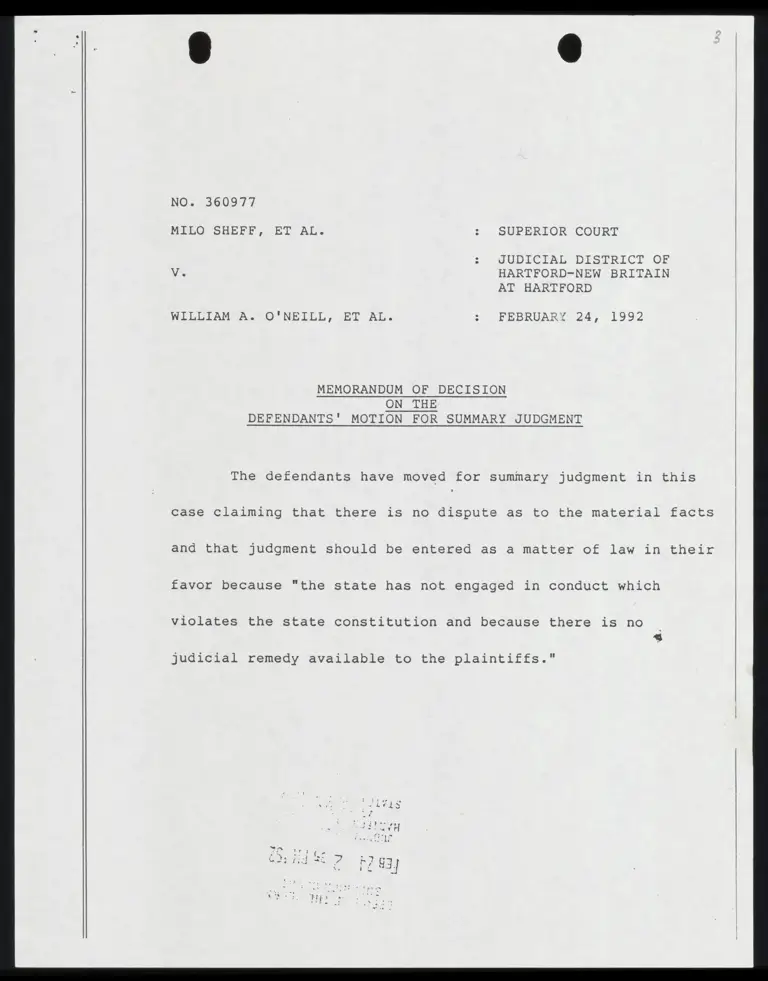

NO. 360977

MILO SHEFF, ET AL.

V.

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, ET AL.

SUPERIOR COURT

JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

HARTFORD-NEW BRITAIN

AT HARTFORD

FEBRUARY 24, 1992

MEMORANDUM OF DECISION

DEFENDANTS

ON THE

MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

The defendants have moved for summary judgment in this

case claiming that there is no dispute as to the material facts

and that judgment should be entered as a matter of law in their

favor because "the state has not engaged in conduct which

violates the state constitution and because there is no

<

judicial remedy available to the plaintiffs."

They make three specific claims in support of their

motion:

1. The plaintiffs’ constitutional rights have not been

violated because the conditions alleged in their complaint are

not the products of state action.

2. The plaintiffs' constitutional rights have not been

violated because "the state has satisfied any affirmative

obligation which arises out of the constitution.”

3. The controversy is not justiciable.

This court; in its memorandum of decision dated May 18,

1990, on the defendants' motion to strike, considered the first

of the foregoing claims in the context of that motion at pages

11 through 14, and ruled that at least at that stage of the

proceedings the plaintiffs were entitled to a full hearing on

the merits of their claims. The plaintiffs assert that the

court should not reconsider that issue because the law of the

case has been established by the court's prior decision.

"New pleadings intended again to raise a question of law

which has been already presented on the record and determined

adversely to the pleader are not to be favored." Wiggin v.

Federal Stock & Grain Co., 77 Conn. 507 at 516. Where a matter

has previously been ruled upon by a judge in the same case, he

may treat that decision as the law of the case and should

hesitate to change his own ruling if he is of the opinion that

it was correctly decided, "in the absence of some new or

overriding circumstance." Breen v. Phelps, 186 Conn. 86, 99.

The principal factual basis for the defendants' claim

that proof of some type of state action is an indispensable

element of the plaintiffs' constitutional claims is an

affidavit of Gerald L. Tirozzi, a former commissioner of

education for the state of Connecticut, which states that with

the exception of regional school districts, "existing school

district boundaries have not been materially changed over the

last 80 or so years." He also asserts that no child in this

State, to his knowledge, has ever been assigned to a school

district in this State on the basis of race, national origin,

socio-economic status, or status as an "at risk" student, and

that children have always been assigned to particular school

districts exclusively on the basis of their city or town of

residence.

The plaintiffs argue that the requirement of "state

action" is not a prerequisite for the establishment of their

constitutional claims because they have alleged "de facto”

rather than "de jure" racial and economic segregation. The

theory of their case as they state it in their brief (p. 5) is

that they are seeking relief from "the harms that flow from the

present condition of racial and economic segregation that in

fact deprives Hartford area school children of their right to

equality of educational opportunity [and that] the intent of

the defendants is therefore immaterial.”

Public schools are creatures of the state, and whether

the condition whose constitutionality is being attacked is

"state-created or state—assisted or merely state—perpetuated

should be irrelevant" to the determination of the -

constitutional issue. Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver,

Colorado, 413 U.S. 189, 227 (1973). Educational authorities on

the state and local level are so significantly involved in the

control, maintenance and ongoing supervision of their school

systems as to render existing school segregation "state action”

under a state's constitutional equal protection clause.

Crawford v. Board of Education of the City of Los Angeles, 551

P.2d 28, 36 (Cal. 1976).

The defendants' claim, as stated in their brief (p. 50),

that "direct and harmful state action 1s necessary to support

claims under the education provision in Article VIII, §1 of the

state constitution", is based on the Supreme Court's recent

decision in Savage v. Aronson, 214 Conn. 256, which upheld the

constitutionality of the action of the commissioner of income

maintenance in reducing the period of eligibility for families

on AFDC from 180 to 100 days. One of the claims made by the

plaintiffs in that case was that their children's

constitutional rights to equal educational opportunity would be

violated because of the harmful effect upon them of frequent

school transfers. Id. 286. :

9

The Court's response to this argument was that the

children's hardship was a result of the "difficult financial

circumstances they face, not from anything the state has done

to deprive them of the right to equal educational opportunity."

Justice Glass in his dissent (p. 288) stated that the majority

had apparently adopted the state's argument that it was not

responsible for the consequences of poverty.

The United States Supreme Court has also stated in the

public housing context that "the Constitution does not provide

judicial remedies for every social and economic ill." Lindsey

v. Normet, 405 U.S. 56 at 74 (1972). It has acknowledged,

however, that although public education is not a right

guaranteed by the Constitution, it is nevertheless not merely

some governmental "benefit" indistinguishable from other forms

of social welfare legislation. Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202,

221-22 (1982).

It is also important to recognize that the plaintiffs in

this case have raised an issue that was not decided in Horton

v. Meskill, 172 Conn. 615, namely, whether the state's

constitutional obligation under its Education Clause imposes

requirement of a specific substantive level of education" in

particular area of the state. See Abbott v. Burke, 575 A.2d

359 at 368 (N.J. 1990). In order to rule on the plaintiffs’

claims, therefore, the court must more particularly define "the

scope and content of the constitutional provision[s]" upon

which the plaintiffs rely. Id. 367.

For the foregoing reasons, as this court stated in its

ruling on the defendants' motion to strike, the question of

whether or not the state's action or failure to act rises to

the level of a constitutional violation goes to the merits of

this case because it constitutes a "bona fide and substantial

question or issue in dispute ... which requires settlement

between the parties ..." by way of the declaratory judgment

which the plaintiffs seek. Practice Book §390(b).

The defendants' second claim in support of their motion

is that "the state has satisfied any affirmative obligation

which arises under the constitution." They point to the

"undisputed fact" that the plaintiffs have been unable in the

course of pretrial discovery to disclose "any distinct

affirmative act, step or plan which, if implemented, wou gd have

sufficiently addressed the conditions about which the

plaintiffs complain.”

They also argue that despite the complexity of the

problems reflected by the plaintiffs' inability to offer any

alternative approaches that would pass constitutional muster,

the general assembly has adopted, and the defendants have

implemented, a great number of programs "specifically designed

to assist the Hartford public schools ... in their effort to

meet the special needs of urban children who are largely

members of minority groups, often poor, and, in large numbers,

'at risk'". Defendants' Brief, p. 61. They have submitted a

large amount of data furnished by the department of education

(Exhibits 3 and 4) describing the various state and

interdistrict programs that have been developed to address

these problems.

The materials furnished by the defendants tend to show

that the objectives of these programs are being met and are

having a positive effect on the problems that they were

designed to address. The plaintiffs, on the other hand, have

submitted counteraffidavits from Hartford area school ‘

administrators who state that in their opinion the Se ta’s

efforts have been ineffectual and that the fiscal and

statistical data in the defendants' affidavits are inaccurate

and misleading.

Although the defendants acknowledge that Article VIII,

§1, imposes an affirmative obligation on the state to provide

free public elementary and secondary education and also makes

education a fundamental right, they claim that it cannot be

construed either alone or in conjunction with the equality of

rights clause (article first, §1), and the equal protection

clause (article first, §20), to impose a specific obligation on

the general assembly to address the problems of which the

plaintiffs complain in any way other than it deems appropriate

in its legislative judgment. The defendants' argument, in

essence, is that what is "appropriate legislation" within the

meaning of the Education Clause MAY be determined by the courts

only where it involves the funding of the state's educational

system but they may not constitutionally impose a requirement

of a specific substantive level of education.

9

The state's arguments in this case are much the same as

those made in Abbott v. Burke, 575 A.2d 359 (N.J. 1990), to

justify a ruling by the state commissioner of education that

his department's funding and administration of the Public

School Education Act, which that court had found to be

constitutional in prior cases "assured a thorough and efficient

education" as required by the state constitution. Id. 365.

The court reversed the commissioner's ruling on the ground that

"[tlhe proofs compellingly demonstrate that the traditional and

prevailing educational programs in these poorer urban schools

were not designed to meet and are not sufficiently addressing

the pervasive array of problems that inhibit the education of

poorer urban children." Id. 363.

The New Jersey Supreme Court stated in Abbott that the

constitutionally mandated educational opportunity was not

limited to "expenditures per pupil, equal or otherwise, but

[was] a requirement of a specific substantive level of

education.” Id. 368. It should also be noted that the opinion

makes reference to the failure of the so-called "effective

schools" programs in both New Jersey and Connecticut to fully

achieve their goals. Id. 404-405 n.38. :

3

The defendants' restrictive views as to the permissible

scope of judicial inquiry into the state's constitutional and

statutory responsibilities in the field of public education

bring to mind the views of the lone dissenting Justice in

Horton I, who took the position that the constitution requires

only "legislation which makes education free." Horton v.

-10-

Meskill, 172 Conn. 615 at 658. Nevertheless, in his dissenting

opinion, he acknowledges that a minimal substantive level of

education may be constitutionally required in that "[a] town

may not herd children in an open field to near lectures by

illiterates [but] there is no contention that such situations

exist, or that education in Connecticut is not meaningful or

does not measure up to standards accepted by knowledgeable

leaders in the field of education.” Id. 639.

The plaintiffs in this case have alleged that they have

been deprived of a "minimally adequate education" and are

therefore entitled to a judicial determination of whether the

constitution requires a particular substantive level of

education in the school districts in which they reside.

The defendants' final claim that the conditions of which

the plaintiffs complain are not justiciable was thoroughly

briefed and argued on the defendants' motion to strike, and the

court's reasons for rejecting that claim are fully stated at

pages 7 through 11 of the court's memorandum.

The court will treat that portion of its decision on the

motion to strike as the law of the case because "it is of the

k4 3

opinion that the issue was correctly decided" and the

defendants' argument is repetitive. Breen v. Phelps, 186 Conn.

86, 99. "Parties cannot be permitted to waste the time of

courts by the repetition in new pleadings of claims which have

been set up on the record and overruled at an earlier stage of

the proceedings." Hillyer v. Borough of Winsted, 77 Conn. 304

at 306.

For all of the foregoing reasons, the defendants’

motion for summary judgment is denied.