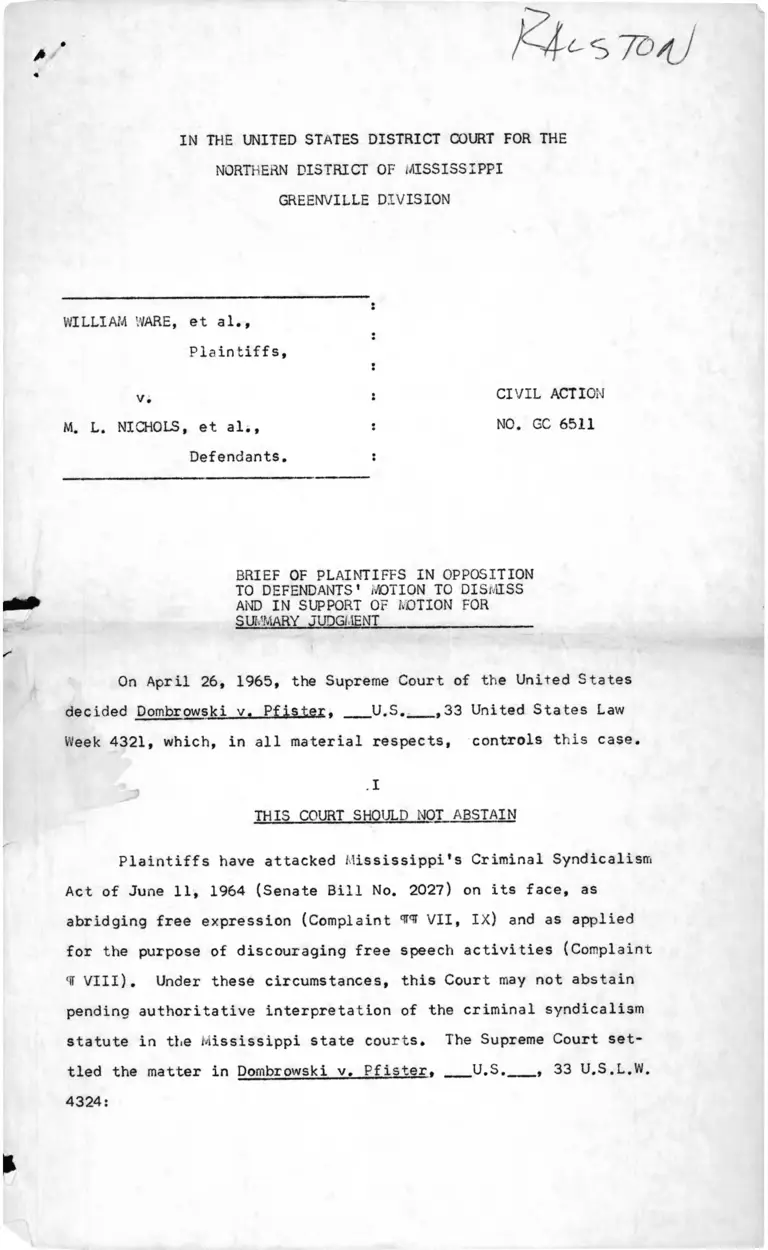

Ware v. M.L. Nichols Brief of Plaintiffs in Opposition to Motion to Dismiss and in Support of Motion for Summary Judgement

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ware v. M.L. Nichols Brief of Plaintiffs in Opposition to Motion to Dismiss and in Support of Motion for Summary Judgement, 1965. ca33c97e-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/993efdee-88b8-412f-99b7-f410acbd7778/ware-v-ml-nichols-brief-of-plaintiffs-in-opposition-to-motion-to-dismiss-and-in-support-of-motion-for-summary-judgement. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

̂s JO

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

GREENVILLE DIVISION

WILLIAM WARE, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

M. L. NICHOLS, et al.,

Defendants.

CIVIL ACTION

NO. GC 6511

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS IN OPPOSITION

TO DEFENDANTS' MOTION TO DISMISS

AND IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR

SUMMARY JUDGMENT_________________

On April 26, 1965, the Supreme Court of the United States

decided Dombrowski v. Pfister. ___U.S.___,33 United States Law

Week 4321, which, in all material respects, controls this case.

.1

THIS COURT SHOULD NOT ABSTAIN

Plaintiffs have attacked Mississippi's Criminal Syndicalism

Act of June 11, 1964 (Senate Bill No. 2027) on its face, as

abridging free expression (Complaint w VII, IX) and as applied

for the purpose of discouraging free speech activities (Complaint

*¥ VIII). Under these circumstances, this Court may not abstain

pending authoritative interpretation of the criminal syndicalism

statute in the Mississippi state courts. The Supreme Court set

tled the matter in Dombrowski v. Pfister. ___U.S.___, 33 U.S.L.W.

4324:

The District Court also erred in holding

that it should abstain pending authoritative

interpretation of the statutes in the state

courts, which might hold that they did not

apply to SCEF [one of the plaintiffs seek

ing injunctive relief against enforcement of

Louisiana's anti-subversive laws], or that they

were unconstitutinal as applied to SCEF.

We hold the abstention doctrine is inappropriate

for eases -such as the present one where unlike

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, statutes are justi

fiably attacked on their face as abridging free

expression, or as applied for the purpose of

discouraging protected activities.

II

THE MISSISSIPPI CRIMINAL SYNDICALISM

ACT IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL ON ITS FACE

Mississippi's Criminal Syndicalism Act on its face abridges

First-Fourteenth Amendment freedoms of speech, assembly and

petition and is unduly vague, uncertain and broad.

A. It is now settled that the First-Fourteenth Amendment

guarantee of free speech protects the advocacy of the abstract

doctrine of violent overthrow of the government. Yates v. United

States. 354 U.S. 293 (1957); Noto v. United States. 367 U.S. 290

(1961). Under this principle, the Criminal Syndicalism Act is

void on its face as an abridgment of free speech because it

_!/

makes criminal the mere advocacy of the advocacy of crime. This

is seen from the following analysis of the Act:

1/ As the Supreme Court said in Noto v. United States. 367 U.S.

at 297-98:

We held in Yates. and we reiterate now, that the

mere abstract teaching of Communist theory, including

the teaching of the moral propriety or even moral

necessity for a resort to force and violence, is not

the same as preparing a group for violent action and

steeling it to such action.

2

Section 2(1). Any person is guilty of a felony who

advocates, instigates, suggests, teaches or aids and

abets the propriety of committing [sic] the doctrine or

precept which advocates, teaches, or aids and abets the

commission of crime or other unlawful acts or methods of

terrorism as a means of accomplishing or effecting a change

in agricultural or industrial ownership or control or in

effecting any political or social change.

Section 2(2). Any person is guilty of a felony who

justifies or attempts to justify the doctrine or precept

which advocates, teaches, or aids and abets the commission

of crime or other unlawful acts or methods of terrorism as

a means of accomplishing or effecting a change in agri-

r.cuLjtura 1 or industrial ownership or control or in effect

ing any political or social change with intent to exemplify,

approve, spread, advocate, instigate, teach, aid, suggest

or further the doctrine or precept which advocates, teaches,

or aids and abets the commission of crime or other unlawful

acts or methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing

or effecting a change in agricultural or industrial owner

ship or control or in effecting any political or social

change.

Section 2(3), Any person is guilty of a felony who

prints, publishes, edits, issues, circulates, sells, dis

tributes or publicly displays any book, paper, pamphlet,

document, poster, handbill, or written or printed matter

in any form whatsoever containing, advocating, instigating,

advising, suggesting, aiding and abetting, or teaching the

doctrine or precept^which advocates, teaches, or aids and

abets the commission of crime or other unlawful acts or

methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing or effect

ing a change in agricultural or industrial ownership or

control, or in effecting any political or social change.J2j

Section 2(4). Any person is guilty of a felony who

organizes or helps to organize or knowingly becomes a

member of, or voluntarily assembles with any society, organi

zation, group; or assemblage of persons organized, formed,

or assembled to advocate, teach, aid and abet the doctrine

or precept which advocates, teaches, or aids and abets the

commission of crime or other unlawful acts or methods of

terrorism as a means of accomplishing or effecting a change

in agricultural or industrial ownership or control, or in

effecting any political or social change.

Section 2(5). Any person is guilty of a felony who

practices or commits any act advised, advocated, taught, or

aided -and abetted by the doctrine or precept which ad

vocates, teaches, or aids and abets the commission of crime

or other unlawful acts or methods of terrorism as a means

of accomplishing or effecting a change in agricultural or

industrial ownership or control or in effecting any politi

cal or social change with intent to accomplish a change

in agricultural or industrial ownership or control or effect

ing any social or political change.

2/ In addition to the other grounds of invalidity advanced,

infra. 2(3) lacks any scienter requirement and is eo ipsq bad

under Smith v. California. 361 U.S. 147 (1959).

3 -

Section 3. Whenever two or more persons assemble or

consort for the purpose of advocating, encouraging, teach

ing or suggesting the doctrine or precept which^advocates,

teaches, or aids and abets the commission of crime or other

unlawful acts or methods of terrorism as a means of accom

plishing or effecting a change in agricultural or industrial

ownership or control or in effecting any political or social

change, such assemblage is unlawful and every person volun

tarily participating therein by his presence is guilty of a

felony.

Section 4. The owner, lessee, agent, superintendent,

janitor, caretaker,-or other person in charge or occupant

of any place, building, room or rooms, or structure who

knowingly permits therein any assembly or consort of per

sons prohibited by the provisions of Section 3 of this act

is guilty of a misdemeanor.

Further abstracting the statute, it is seen that the follow

ing acts are punishable:

Suggesting the propriety of the doctrine, etc. (2(1));

Attempting to justify the doctrine, etc., (2(2));

Publishing a book containing the doctrine, etc.,

(2(3));

Assembling with persons assembled to teach the doc

trine (2(4));

Committing any act advised by the doctrine, etc.,

(2(5));

Being present at any assemblage assembled for the

purpose of suggesting the doctrine, etc., (3); or

Permitting the assembly of persons violating section

3(4).

It is difficult to imagine a statute more patently an abridg

ment of First-Fourteenth Amendment guarantees of free speech,

press and assembly. The statute purports to reach speech of a

character totally without the sphere of criminal incitement; its

invalidity is clear beyond peradventure. Kingsley Copp> ..y.

Regents. 360 U.S. 684, 689 (1959); New York Times. .Gp .̂ v . Sullivan.

376 U.S. 254, 269-71 (1964); Garrison v. Louisiana. 379 U.S. 64,

70, 73-74 (1964).

4 -

Presumably, a teacher would violate 2(l) if he approvingly

taught his class about the Boston Tea Party. 3/ A person who

attempted to justify the actions of his state's governor in

committing criminal contempt in a civil rights matter would fall

under the ban of 2(2). No doubt the Government Printing Office

is in violation of 2(3) for printing editions of the Declaration

of Independence, for that document contains the language:

"Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends

[life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness] it is the right of

the people to alter or abolish it . . . . When a long train of

abuses and usurpations pursuing invariably the same object evinces

a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right

it is their duty to throw off such government and to provide new

guards for their-future security." A worker who attended a labor

union meeting at which an illegal strike was advocated might well

be subjected to prosecution under 2(4).

Any person who reads Das Kapital. an act doubtlessly advised by

communist doctrine, should fear prosecution under 2(5), if he reads

with the requisite intent. A Sunday stroller who happened upon

a street meeting of persons calling themselves syndicalists, and

who was drawn into discussion with them, might well fear prosecu

tion under section 3.

_2/ Section 2(l) is perhaps the most pernicious section of all,

for it makes it a felony to "suggest . . . the duty [or] propriety

of committing crime . . . as a means of . . . effecting any politi

cal or social change." This vague and sweeping language would not

only have made Thomas Jefferson a felon (see text, infra.) but also

Henry David Thoreau for his essay "On The Duty of Civil Disobedient

and Mohandas K. Gandhi for his various writings based on Thoreau.

It is a matter of common knowledge that a central philosophy of the

civil rights movement is derived largely from these writings of

Thoreau and Gandhi. (Cf,, Brief of Defendants, p. 10.)

5

B, So analyzed, the Mississippi criminal syndicalism statute

must also fall because it is unduly vague, uncertain and broad.

In the area of First Amendment freedoms, the effect of an over

broad statute is peculiarly pernicious, as it creates a "danger

zone", see Dombrowski v. Pfister. supra. 33 U.S.L. Week at 4325,

within which protected expression may be inhibited.

In Dombrowski v. Pfister. supra, and Baogett v. Bullitt, 377

U.S. 360 (1964), the Supreme Court struck down for overbreadth

state statutes which sought to punish "subversive" organizations

or persons.

In Baaaett v. Bullitt. 377 U.S. 360 (1964), the Supreme Court

held that a state statute requiring state employees to take an oath

as a condition of employment that they were not "subversive" per

sons denied due process because it was unduly vague, uncertain and

broad. The court described the oath in the following terms (377

U.S. at 360):

A teacher must swear that he is not a subversive

person: that he is not one who commits an act or

who advises, teaches, abets or advocates by any

means another person to commit or aid in the com

mission of any act intended to overthrow or alter,

or to assist the overthrow or alteration, of the

constitutional form of government by revolution,

force or violence.

The Court found the oath lacking "in terms susceptible of

objective measurement" (377 U.S. at 367); the Court found that it

(as well as the complaining state-employed teachers) was unable to

answer rudimentary questions, such as: "Does the statute reach

endorsement or support for Communist candidates for office? Does

it reach a lawyer who represents the Communist Party or its members

or a journalist who defends constitutional rights of the Communist

Party or its members or anyone who supports any cause which is like

wise supported by Communists or the Communist Party?"

Similar questions may be asked of the application of Mississippi

Criminal Syndicalism Act; the answers will be similarly lacking.

For example, does the statute reach a minister who "suggests" that

6

an inter-racial couple go North to be married, in violation of

Mississippi's anti-miscegenation statute? _4/ Does the statute

reach the attempt by a newspaper editor to justify in -print the

conduct of a racially integrated group riding in a taxicab, in vio

lation of Mississippi law. 5/ in order to promote full social equaliv

between the races? Does the statute reach the person who attends

a meeting of a civil rights organization held for the purpose of

proposing means for eliminating segregation? _6/ If anything, the

statute in Baaoett v. Bullitt is less vague than Mississippi's

criminal syndicalism statute.

The Court in Dombrowski v. Pfister. following Baggett v. Bullitt,

struck down the Louisiana Subversive Activities and Communist Con

trol Acts for vagueness, saying:

Where, as here, protected freedoms of expression

and association are similarly involved, we see no

controlling distinction in the fact that the defi-

nition is used to provide a standard of criminality

rather than the contents of a test oath.

This Court is bound by the adjudications in Baggett v. Bullitt

and Dombrowski v. Pfister. whose teachings on the vagueness doc

trine clearly control this case; insofar as Whitney v. California.

274 U.S. 357 (1927) suggests a different result, it has been sub

silentio overruled by these decisions. Whitney rejected a vague-

4/ Miss. Code Ann., 1942, §§ 459, 2000. The act achieves total

obscurity with the word "suggests”; there is no legislative or judi

cial gloss available anywhere giving any indication what kind of

conduct would render a person criminally liable under that phrase

ology. A better hornbook example of the indispensability of the

void-for-vagueness doctrine in the area of free speech could scarcely

be invented.

_5/ Miss. Code Ann., 1942, §§ 3499, 3500.

6/ See Miss. Code Ann., 1942, § 2056.

7

ness attack on the California Criminal Syndicalism Act, 274 U.S.

at 368-69, _Z/ discussing the claim against the background of

cases like International Harvester Co, v, Kentucky, 234 U.S. 216

(1914); United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co.. 255 U.S. 81 (1921);

Nash v. United States. 229 U.S. 373 (1913); and Miller v. Strahl,

239 U.S. 426 (1915) -- all decisions involving challenges to

economic regulatory legislation. But those cases, along with

Whitnev. have been drained of all vitality in the First-Fourteenth

Amendment area. In a line of decisions from Strombera v. California.

283 U.S. 359 (1931), through Winters v. New York. 333 U.S. 507, 509-

10, 517-18 (1948), Smith v. California. 361 U.S. 147, 151 (1959),

and United States v. National Dairy Products Co.. 372 U.S. 29, 36

(1963), to Cox v. Louisiana. 379 U.S. 536, 551-52 (1965), the

Supreme Court has developed a standard of impermissible vagueness

in First-Fourteenth Amendment cases far different from that em

ployed in economic regulation cases. This development was explicit

ly recognized in the National Dairy Products case, 372 U.S. at 36:

[W]e also note that the approach to "vagueness"

governing a case like this is different from

that followed in cases arising under the First

Amendment. There we are concerned with the

vagueness of the statute "on its face" because

such vagueness may in itself deter constitutionally

protected and socially desirable conduct. See

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88, 98, 84 L.ed

1093, 1100, 60 S.Ct. 736 (1940); NAACP v. Button,

371 U.S. 415, 9 L.ed 2d 405, 83 S.Ct. 328. N0>

such factor is present here where the statute is

directed only at conduct designed to destroy com

petition, activity which is neither constitutionally

protected nor socially desirable . . . . The

reliance of National Dairy . . . on First Amendment

cases is therefore misplaced.

7/ The only section of the California Criminal Syndicalism Act

presented to and upheld by the Supreme Court provided:

Sec, 2 Any person who: • . . (4) organizes

or assists in organizing, or is or knowingly

becomes a member of, any organization, society,

group or assemblage of persons organized or

assembled to advocate, teach or aid and abet

criminal syndicalism . . .

Is guilty of a felony and punishable by

imprisonment.

(Note continued on following page)

- 8 -

And nowhere is the special significance of the vagueness doctrine

in First-Fourteenth Amendment cases more clearly recognized than

in Dombrowski v. Pfister. 33 U.S.L.W. at 4323:

Because of the sensitive nature of constitutionally

protected expression, we have not required that all

of those subject to overbroad regulations risk pro

secution to test their rights. For free expression --

of transcendent value to all society, and not merely

to those exercising their rights -- might be the loser,

Cf, Garrison v. Louisiana. 379 U.S. 64, 74-75. For

example, we have consistently allowed attacks on

overly broad statutes with no requirement that the

person making the attack demonstrate that his own

conduct could not be regulated by a statute drawn

with the requisite narrow specificity. Thornhill v.

Alabama. 310 U.S. 88, 97-98; NAACP v. Butrcn. [371 U.S.]

at 432-433; cf. Aotheker v. Secretary of State. 378

U.S. 500, 515-517; United States v. Raines. 362 U.S.

17, 21-22. We have fashioned this exception to the

usual rules governing standing, see United States v.

Raines, s upr a. because of the " . . . danger of

tolerating, in the area of First Amendment freedoms,

the existence of a penal statute susceptible of sweep

ing and improper application." NAACP v. Button.

[371 U.S.] at 433.

Finally, defendants purport to justify the criminal syndicalism

statute by claiming (Defendants’ Brief, pp. 10-11) "that the real

purpose of the act was to prevent activities of certain groups and

organizations about which there has recently been considerable

publicity, and in an effort to protect members of the class who

plaintiffs purpose to represent . . . . In rural Mississippi, where

the majority of Negroes are tenant farmers or sharecroppers, it is

not hard to see that the Mississippi criminal syndicalism act can

be effectively used to protect them from the commission of the very

acts condemned by the Mississippi statute."

Such a statement reflects a serious misconception of our con

stitutional scheme of government:

(continued)

Mississippi’s section 2(4) significantly alters the California

model, in that it makes it a felony to voluntarily assemble with

such an organization -- quite irrespective of the defendant s know

ledge of the character of the organization. Therefore, this sec

tion is invalid under the rule of Wieman v. Updegralf, 344 U.S, 183

(1952), as well as for the other reasons advanced herein.

9 -

Those who won our independence by revolution

were not cowards. They did not fear political

change. They did not exalt order at the cost

of liberty. To courageous, self-reliant men,

with confidence in the power of free and fear

less reasoning applied through the processes of

popular government, no danger flowing from speech

can be deemed clear and present, unless the

incidence of the evil apprehended is so imminent

that it may befall before there is opportunity

for full discussion. If there be time to expose

through discussion the falsehood and fallacies,

to avert the evil by the processes of education,

the remedy to be applied is more speech, not

enforced silence. (Justice Brandeis, concurring,

in Whitnev v. California. 274 U.S, at 377.)

Ill

PLAINTIFFS ARE ENTITLED TO INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

There can be no doubt that under the standards set forth in

Dombrowski v. Pfister. supra, plaintiffs have adequately alleged

irreparable injury sufficient to support injunctive relief. The

direction in which this Court should proceed is clearly marked by

the treatment directed in the Dombrowski case on remand. There,

the Court directed the District Court to proceed with the "prompt

framing of a decree restraining prosecution of the pending indict

ments against the individual appellants • . . and prohibiting further

acts enforcing the sections of the Subversive Activities and Commu

nist Control Acts here found void on their face."

Since the Mississippi Criminal Syndicalism Act is void on its

face as violative of free speech guarantees and for vagueness, this

Court is required, under Dombrowski. to grant plaintiffs' motion

for summary judgment. On any view of the case however, defendants

motion to dismiss must still be denied, for the allegations con

tained in Will of plaintiffs' complaint clearly state a cause of

action, alleging as they do that defendants are "invoking the statute,

in bad faith to impose continuing harassment in order to discourage

10

[plaintiffs'] activities

33 U.S.L.W. at 4324).

It (Dembrowski v. Pfister. supra.

Respectfully submitted,

CARSIE A. HALL

JACK H. YOUNG

115''2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

R. JESS BROWN

125^ North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

HENRY M. ARONSON

538^ North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN ZARR

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

Of Counsel