Bazemore v. Friday Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants P.E. Bazemore et al.

Public Court Documents

February 15, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bazemore v. Friday Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants P.E. Bazemore et al., 1983. 07fd2a06-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/994c3db1-e5d0-4333-ad14-1b5bb03a650f/bazemore-v-friday-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants-pe-bazemore-et-al. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

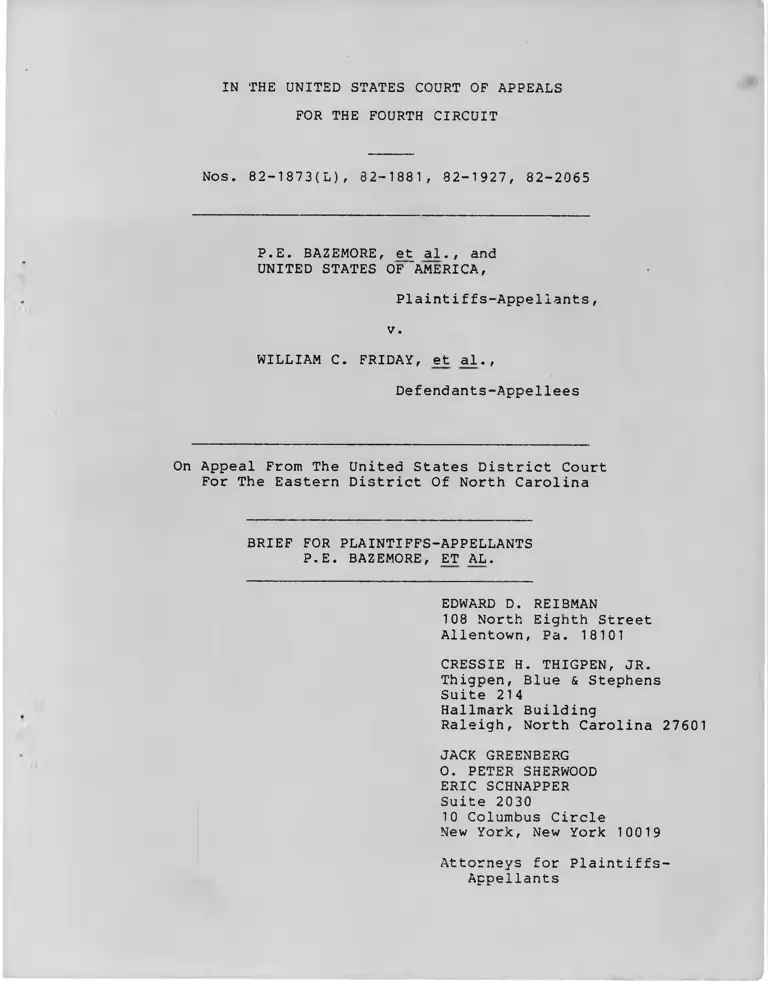

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 82-1873(L), 82-1881, 82-1927, 82-2065

P.E. BAZEMORE, et al. , and

UNITED STATES OF 'AMERICA,

Plaintiffs-AppeIIants,

v.

WILLIAM C. FRIDAY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District Of North Carolina

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

P.E. BAZEMORE, ET AL.

EDWARD D. REIBMAN

108 North Eighth Street

Allentown, Pa. 18101

CRESSIE H. THIGPEN, JR.

Thigpen, Blue & Stephens

Suite 214

Hallmark Building

Raleigh, North Carolina 27601

JACK GREENBERG

0. PETER SHERWOOD

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cases: Page

Statement of the Issues ............ 1

Statement of the Case .............................. 2

Statement of Facts ............... .................. 3

ARGUMENT ......................................... 5

I. THE DEFENDANTS ARE UNLAWFULLY PROVIDING

SERVICES AND MATERIALS TO SEGREGATED

4-H AND EXTENSION HOMEMAKER CLUBS .......... 5

(1) NCAES Policies ........... 6

(2) The Applicable Legal Standards ....... 17

II. THE DEFENDANTS DISCRIMINATED AGAINST

BLACK EMPLOYEES IN SALARIES ...... ........... 24

(1) Pre-1965 Hires ............... 24

(2) Post-1965 Hires ........... 33

(3) The Individual Claims .................. 41

III. THE DEFENDANTS DISCRIMINATED AGAINST

BLACK EMPLOYEES IN SELECTING COUNTY

EXTENSION CHAIRMEN ........................ 45

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN REFUSING TO

CERTIFY THIS CASE AS A CLASS ACTION ___ ..... 54

(1) The Class of Black Actual and Poten

tial Club Members ..... 55

(2) The Class of Black NCAES Employees ...... 57

(3) The Defendant Class ................ 62

CONCLUSION .............................. 64

- l -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pa9e

Bell v. Georgia Dental Ass'n, 231 F. Supp. 299

(N.D. Ga. 1964) 62

Blacksher Res. Org. v. Housing Authority of

the City of Austin, 347 F. Supp. 1138

(W.D. Tex. 1972) ................................... 18

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .... 6

Chisholm v. United States Postal Service, 665

F . 2d 482, 496 (4th Cir. 1981) ............. 38, 42, 49, 50

EEOC v. American National Bank, 652 F.2d

1176 (4th Cir. 1981) ............................... 52

EEOC v. Federal Reserve Bank, ____ F.2d ____

(1983) .............................................. 36

Evans v. Harnett County Bd. of Ed., 684 F .2d

304 ( 4th Cir. 1982) ................................ 30

General Telephone Co. v. EEOC, 446 U.S. 318

( 1980) .............................................. 61

Green v. School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 ( 1968) 20

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218 ( 1964) 23

Hill v. Western Electric Company, Inc.,

596 F .2d 99 (4th Cir. 1979) --- ................. 59

Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962) ....... 62

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 ( 1895) .......... . 32

Simkins v. Moses Cone Memorial Hospital,

323 F . 2d 959 ( 4th Cir. 1963) ...................... 17

Sledge v. J. P. Stevens Co., Inc., 585 F.2d

625 (4th Cir. 1978) ................................ 41, 51

Stastny v. Southern Bell Telephone and Telegraph

Co., 628 F . 2d 267 (4th Cir. 1980) ................. 59

- ii -

Statutes: Page

Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act ...... 6, 7, 10, 18,

25, 31, 32, 55

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act ............ 60

Smith-Lever Act, 7 U.S.C. § 341, et seq............ 3

Other Authorities:

Fifth Amendment .................................... 55

Fourteenth Amendment ............................... 32, 55

7 C.F.R. §§ 8.1-8.10 ............................... 5

7 C.F.R. § 15.3(b)(6)(i) ........................... 18

7 C.F.R. §§ 18.1-18.9 .................... 29

Restatement of Agency (Second) ...................... 62

Rule 23 ............................................. 63

- iii -

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 8 2-1873(L ), 82-1881 , 82-1927, 82-2065

P.E. BAZEMORE, et_ a H , and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff s-Appe H a n t s ,

v.

WILLIAM C. FRIDAY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District Of North Carolina

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. May the North Carolina Agricultural Extension

Service and other defendants provide millions of dollars of

services and materials to all-white 4-H and Extension Homemaker

clubs which

(a) were established by the Extension Service on a

segregated basis, or

(b) are permitted to recruit their members on a

racial basis?

2. Were black employees of the Extension Service

subject to discrimination in the determination of their

salaries?

3. Were black employees of the Extension Service

subject to discrimination in promotions to the position of

county extension chairman?

4. Did the district court err in refusing to certify

this case as a class action?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action was commenced on November 18, 1971, on behalf

of black employees of the North Carolina Agricultural Extension

Service ("NCAES") alleging racial discrimination in employment

and by certain clubs organized and supported by NCAES. (App.

34-35). On April 7, 1972, the United States intervened in the

action alleging discrimination similar to that claimed by the

private plaintiffs.

On October 9, 1979, the district court rejected a motion by

the private plaintiffs and the United States to certify the case

as a class action. (App. 21-24). A subsequent motion to recon

sider the denial of class certification was denied on July 29,

1981. (App. 31-32). On August 20, 1982, following a lengthy

trial, the district court issued a decision rejecting on the

merits what it characterized as the "class-wide claims."

(App. 111-112) and September 17, 1982, (App. 113-16) the

district court issued additional opinions rejecting the claims

of the individual plaintiffs.

The original complaint alleged a wide variety of forms

of discrimination by NCAES against blacks and Indians.

During the eleven years between the filing of the complaint

2

and the district court opinion there were a number of changes

in NCAES practices, some of which are described below. In

light of those developments and the evidence at trial, plain

tiffs press on appeal only three of these substantive claims

— salary discrimination against blacks, discrimination against

blacks in the selection of county extension chairmen, and the

providing of services and material to segregated 4-H and

Extension Homemaker clubs.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

NCAES is a division of the School of Agriculture and Life

Sciences of the North Carolina State University in Raleigh.

The purpose of the NCAES is to provide "useful and practical

information on subjects relating to agriculture and home

economics." Funds for the program are provided by the federal

government under the Smith-Lever Act, 7 U.S.C. §341, et seg.,

by the State of North Carolina, and by each of the 100 counties

in the state. NCAES provides services in four major areas:

home economics, agriculture, 4-H and youth, and community

resources development. The NCAES activities in each county are

supervised by salaried county extension chairman. The other

professional employeees at the county level hold one of six

positions: full, associate and assistant home economics agents

and full, associate and assistant agricultural agents. (App.

37-40).

Prior to August 1, 1965, NCAES was divided into two com

pletely segregated branches, a white branch (which had no formal

racial designation) and a "Negro" branch. The black branch was

3

composed entirely of black personnel and served only black

farmers, homemakers, and youth. The white branch employed no

blacks but on occasion served blacks. In the fifty-one counties

in which the black branch had programs the black and white

programs were operated separately out of different offices.

Although there was no interchange of personnel between the two

organizations, black and white agents had identical responsi

bilities, and their job descriptions were identical except for

the appellation "Negro work" for blacks. The salaries of black

agents in the segregated system were lower than the salaries of

their white counterparts, and black agents had inferior office

space and facilities in the segregated system. (App. 42-44).

In August, 1965, the white and Negro branches of NCAES

were formally merged. At the state and district levels the

black administrative structure was abolished, and its black

personnel were placed in positions with reduced supervisory

responsibility under their white counterparts.—^ At the

county level black and white employees were placed in the

same offices but nothing was done to alter the salary dif

ferentials established prior to that merger. See pp. 31-33,

infra. In every county the chief white agent was given over

all responsibility for the county, while the chief black agent

was stripped of his administrative responsibilities. Prior to

1965 NCAES had established separate all-white and all-black

]_/ Tr. 307-09, 1302, 2917, 5781 ; see Government Proposed

Findings 66-72. The district court adopted findings 66-71.

(App. 44).

4

4-H and Extension Homemaker clubs; after 1965 these clubs

continued to operate on a segregated basis. See pp. 9-11,

infra. Many of their problems that gave rise to this litiga

tion have their roots in the discriminatory practices which

existed prior to 1965 and remained unaltered after that time.

The particular facts relevant to the specific issues raised by

this appeal are set out in detail below.

ARGUMENT

I. THE DEFENDANTS ARE UNLAWFULLY PROVIDING SERVICES

AND MATERIALS TO SEGREGATED 4-H AND EXTENSION

HOMEMAKER CLUBS

The 4-H program is one of the major NCAES activities,

operating in each of the 100 counties of the state. NCAES 4-H

agents are to "recruit, train and utilize volunteers to

establish 4-H clubs and ...[to] utilize materials and plan

educational experiences ..." (DX 197) Federal law restricts

the use of the name "4-H Club" to clubs affiliated with state

2/extension services and certain other organizations.— The

equivalent of 122 full time NCAES employees work on 4-H club

activities. (Tr. 4956). The annual state 4-H budget, which

includes NCAES salaries and materials provided to the clubs,

exceeds $5 million. (Tr. 5069)

Organizing Homemaker clubs is one of the primary respon

sibilities of the home economics agents. These agents meet

2/ 7 C.F.R. §§ 8.1-8.10.

5

regularly with the clubs, give lessons to them, and train

certain club members to provide instruction for other members.

[App. 38]. The lessons include practical advice on such

subjects as food, nutrition, health, clothing, and family

resource management. (App. 38.) Approximately 4-5% of the

NCAES annual budget is used to provide this assistance to

homemaker Clubs. (Tr. 4189)

(1) NCAES Policies

Prior to 1965 both types of clubs, like the rest of the

Extension Service, were deliberately organized on a strictly

racially segregated basis. Every club was either "white" or

"Negro", and recruited individual members on a racial basis.

White clubs were served solely by white agents, while only

black agents worked with black clubs. The segregation of the

4-H clubs was ensured by organizing the clubs at the public

schools, which were themselves segregated by law.—/ Separate

county and state level 4-H and Homemaker activities were

organized for blacks and whites.

Although Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954), made clear that such segregation was forbidden by the

Fourteenth Amendment, North Carolina took no steps to end

it until the adoption of Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act, which mandated termination of federal funds for dis-

3 / Tr. 4203-4. The clubs were moved from the public

schools to private homes in the mid-1960's when school

integration began. Tr. 4201-2.

6

criminatory programs. On August 31, 1965, NCAES provided the

Department of Agriculture with a compliance plan which

asserted that both its 4-H and home economics activities had

4 /been integrated on a state and county level;— that plan,

however, was silent regarding the fate of the segregated 4-H

clubs. It acknowledged that the "[h]ome demonstration clubs

were established on a segregated basis," but did not describe

what new procedures they were to follow.—^ On December

31, 1965, NCAES advised federal authorities that it had re

quested all 4-H and Home Demonstration clubs to provide it with

a statement of assurance that they will not discrim

inate on the basis of race, color, or national origin

.... 6/

That was all that the NCAES proposed to do about the several

thousand clubs which it had deliberately and systematically

established on a racial basis.

Between 1965 and 1980 the size of the 4-H club system

varied considerably. Although a significant group of "inte

grated"—^ clubs emerged, the total number of all-white

clubs has remained largely constant.

4_/ GX 115, Revised Compliance Plans for Meeting the Re

quirements of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, pp. 1-2.

5 / Id. p . 4.

6/ GX 115, Report on Status of Compliance of State Extension

Service Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, As Of

December 31, 1965, p. 3.

1_/ In its reports of club membership NCAES treats as "inte

grated" a white club with even a single black member.

7

All-White 4-H Clubs 8/

Year All-White Clubs

1965 1,474

1968 1,202

1970 1,049

1971 1,058

1972 1,275

1973 1,373

1974 1,353

1975 1,270

1976 1,304

1977 1,246

1978 1,270

1979 1,311

1980 1,348

Beginning in 1972 the NCAES altered its reporting procedures

to distinguish single race 4-H Clubs that were located in

ethnically mixed communities from those that were not.

Notwithstanding the potential for self-serving distortion in

9 /this data,—' it reveals a similar lack of progress:

Single-Race 4-H Clubs1Q,

in "Mixed Communities"— '

Year Clubs

1972 892

1973 964

1974 1,014

1975 906

1976 953

1977 898

1978 920

1979 852

1980 880

8/ App. 1806 (1965); GX 115 (letter of G. Hyatt to E. Kirby,

May 26, 1972) (1968, 1971); App. 2237 (1970-74); GX 11 (1975-80).

9/ This system placed considerable discretion in the hands

of county officials to avoid any appearance of discrimination

merely by classifying all single-race clubs as located in

single-race "communities".

J_0/ App. 1 807, 1 813.

- 8 -

/

In 1980, 5399 blacks were in all-black 4-H clubs in racially

mixed communities. (GX 11).

Even less progress has occurred in desegregating the

Extension Homemaker clubs:

Single-Race Homemaker Clubs— /

All White All Non-White Integrated

Year Clubs Clubs Clubs

1966 1,022 658 0

1968 1,562 569 10

1971 1,449 491 261972 1,378 466 22

Even the handful of "integrated" clubs listed appears to

be inflated.— ^ NCAES, which insists that after 1972 it

13/kept no data on the racial composition of these clubs, — '

advanced no claim in the district court that the number of

integrated clubs has increased significantly since that date.

Extension officials from nine counties testified that in 1981

or 1982 all the Homemaker clubs in their counties remained

14/all-white or all-black, just as they had been in 1965.—

J_1/ App. 1 797-1805.

12/ Of the 22 "integrated" clubs reported in 1972, 10

had only a single member of the less numerous race. Six

had only 2 such members. Four were located on the Cherokee

Indian Reservation. Outside of the Reservation only two

Homemaker clubs in the entire state of North Carolina were

integrated to more than a token degree. GX 7.

13/ GX 160, Deposition of Martha Johnson, Oct. 29, 1981,

pp. 58-60, 70-71.

14/ Deposition of Zackie Harrell, Oct. 15, 1981, p. 56

(Hertford County); Tr. 731-32 (Hertford County), 870 (Caswell

County), 941-2 (Perquimans County), 1079, 1082 (Gates County)

1524-25 (Union County), 1765 (Vance County), 1996 (Wayne

County), 2390 (Jones County), 2449-50 (Washington County).

9

The perpetuation of this system of state established

single-race 4-H and Homemaker clubs was the result of more

than simple inaction on the part of NCAES. For many years

after 1965 agents continued to be assigned to these clubs on

1 5/the basis of race.— A 1972 comparison of the race of

agents and of the groups with whom they met demonstrated in

graphic terms the extent to which such assignments were being

made on a discriminatory basis. All-white Homemaker groups

met with white agents 97.3% of the time, while all-black

groups met with black agents on 96.2% of all occasions. (GX

23). All-white 4-H clubs met with white agents in 95.6% of

all cases, while all-black 4-H clubs worked with black agents

in 89.0% of all cases. (GX. 21). Several officials testified

that, at least prior to 1974, black and white agents were

assigned to clubs on the basis of race. (Tr. 1079, 2020,

2025, 1994). Not until July, 1974, did the Extension Service

even purport to assign agents to 4-H and Homemaker clubs on

a non-racial basis. (App. 1834). It is clear that for at

16/least 10 years— ' after the adoption of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act NCAES personnel continued to service all-black and

all-white clubs in North Carolina on a racial basis. That

decade of illegality cannot have failed to impress upon the

members and leaders of the clubs the state's tacit approval

15/ See also GX 115, Revised Compliance Plans for Meeting the

Requirements of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, p. 2.

16/ Even in 1980 there was still a significant disparity

in the race of agents assigned to meet with white and black

groups. GX 35.

10

of organization along racial lines.

On January 15, 1973, the Department of Agriculture

issued affirmative action guidelines requiring that "newly

organized 4-H and Homemakers Clubs which serve a community or

area of interracial clientele must be interracial in composi

tion in order to be eligible for assistance from the Extension

Service". (App. 1905). No services were to be provided to

a new single race club in an integrated area unless "all

reasonable efforts have been made to recruit individuals from

all racial groups." (Id.).

Apparently in response to this federal directive, officials

of the Extension Service met in March, 1974, to formulate new

measures to integrate the large number of single-race clubs.

They initially recommended that no new single-race clubs be

permitted in bi-racial communities unless "sincere but unsuc

cessful efforts were made to have an integrated membership."

(App. 1823)— / Such efforts would have had to be documented

by a statement indicating:

(a) that ten (10) individuals of the "other" race

were given personal invitations to participate (in

cluding descriptions of the activities of the proposed

club), (b) the names and addresses of the individuals,

(c) the name of the person issuing the invitation

to each person and (d) the date issued. The spirit

of the policy on "invitations to join" is that

it be personal (one-to-one) and not an announce

ment in the press or at a meeting, although this

method may be used to supplement the personal

invitation." (App. 1824).

The March 1974 meeting also proposed that steps be taken to

17/ Another staff proposal would have forbidden the creation

of new single-race clubs in mixed areas under any circumstances.

(App. 1829).

disestablish the existing single-race clubs, many of which

had originally been segregated by the state itself.

A program will be undertaken to achieve a voluntary

desegregation of all uniracial clubs in biracial com

munities.... Voluntary desegregation will be re

quested. Multiple approaches will be suggested,

such as (a) combining clubs, (b) recruiting from

the "other" race in the community, (c) joint meetings

of clubs for educational programs .... (App. 1827).

The Extension Service, however, rejected both of these specific

proposals, as well as the USDA Guidelines requiring "all

reasonable efforts" to integrate new clubs. It adopted instead

certain so-called "civil rights initiations" that merely

require that the creation of new clubs

be announced to the public by radio and newspapers

including the approximate location or area served

by the club, its purposes and the fact that it is

open to all people without regard to race.

(App. 1840, 1987).

In March 1977, Don Stormer, the state director of the

4-H programs, issued a directive to district extension

chairmen ordering that, as required by the USDA guidelines,

"a reasonable effort" be made to integrate new 4-H clubs.

(App. 1839). A month later, however, that directive was

rescinded. Extension officials issued instead a new statement

expressly distinguishing the Extension Service policy from

the more stringent USDA regulations:

1. If we are asked what affirmative action requires 1 /

in formation of new 4-H and Homemaker clubs, then the

correct response is to "make reasonable efforts" to

integrate these units, basically as defined in Dr.

Stormer's memo of March 25, 1977.

1/ See "Title 9, Equal Opportunity Administrative

Regulations," USDA, November 18, 1976.

12

2. If we are asked what the policy of the North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service is with

respect to affirmative action, then reference

must be made to the "1974 Civil Rights Initiatives"

which were agreed upon by the Administration....

(App. 1845-46). The officials explained that the state policy

was different than that required by the federal regulations

because the Extension Service "is essentially 'sheltered' from

discrimination issues until the pending litigation is settled,"

and because "counsel advised that a court order resulting from

the civil rights suit would likely require steps in addition to

any affirmative action measures then being implemented." (Id. ) .

In September 1979, Dr. D. G. Harwood, the Assistant

Director for Agricultural Special Programs proposed that, as

had long been required by the 1973 USDA guidelines, NCAES

make "all reasonable efforts" to integrate new 4-H and

Extension Homemaker clubs. Harwood noted that the NCAES

Director himself "realize[d] that often participation is not

encouraged through simply notifying minorities through mass

media outlets," and pointed out that the previous director

had "refused to allow implementation" of that USDA guideline,

(App. 1850; GX 215). The Administrative Council of the

Extension Service initially agreed to Harwood's proposal to

implement this USDA "all reasonable efforts" rule." (App.

1855, 1959-62). Subsequently, however, Howard Manning, Sr.,

counsel for the Extension Service, advised NCAES that he

opposed such further affirmative steps as inconsistent with

the defense he proposed to offer in this litigation that the

Service was already achieving integration and that a "rigid

13

affirmative action program" would simply drive members out of

the clubs. Even though the case had not yet come to trial,

Manning assured Harwood that "the judge understands this."

(App. 1904). Harwood and Manning agreed "that ultimately we

will be forced to get into the 'all reasonable efforts'

program, but perhaps it might be best to wait until our civil

action is resolved." (Id.). Harwood noted that such active

recruitment of minorities for new all-white clubs would cause

"a lot of resistance in our communities among clientele" and

"a lot of dissension" within the Service itself. (Id. ) .

Following these recommendations the proposal to implement the

USDA "all reasonable efforts" guidelines were rejected for

the third time. (Tr. 4284).

In sum, the North Carolina Extension Service, which

deliberately created many of the segregated clubs in the

first instance, has overall a policy of benign indifference

towards their continued existence. Dr. Stormer testified

that there was no state policy in favor of integrating these

clubs. (App. 981). Extension agents were never given

instructions to go out and try to integrate the single-race

clubs. (Tr. 4299) An agent who brought about such integra

tion on his or her own initiative would receive no credit for

that work that might affect his or her promotion or salary

(Tr. 4298); an agent who made substantial progress in inte

grating these clubs would not be rated more highly than one

who made absolutely no progress. (App. 1133). Although

extension agents train the volunteers who recruit members for

14

new or existing clubs, it is not NCAES's policy to train,

instruct or encourage white volunteers to solicit blacks to

join their clubs. (Tr. 4372-74, 5112-13). No all-white club

has ever been threatened with the denial of a single state

service if it did not recruit or obtain black members. (App.

957-60, 994).

NCAES's general attitude was described by one of its

county chairmen as follows:

We have not made an effort to integrate for integra

tion's sake. We have not, you know, frowned on it.

If it happens, we'd be glad for it to happen, but

it hasn't happened. 18/

So long as an existing all-white club does not actually reject

a black applicant, the state simply did not care if it con

tinues to operate as an all-white organization, The club

leaders are neither forbidden nor even asked not to recruit

on a discriminatory basis. If those leaders intentionally

recruited only whites for an existing club, NCAES would take

no action whatever. If whites were recruited in this dis

criminatory fashion for a new all-white club, the sole

response of NCAES would be to issue a press release announc

ing the club's creation — a measure which the state itself

recognized was often ineffective. (App. 1850, GX 215). Dr.

Stormer conceded that, under the present NCAES policies, and

in light of the miniscule rate of progress made prior to

trial, it would take "forever" to eliminate all one-race

clubs in mixed communities. (Tr. 1165-66).

18/ Deposition of Z. W. Harrell, October 15, 1981, p. 56.

15

NCAES officials offered conflicting and unpersuasive

explanations for these policies. Dr. Stormer, the director of

the 4-H programs, asserted that if the single-race clubs were

merged, and individuals thus denied the opportunity to join a

black club or a white club, members of the public would simply

refuse to join the clubs or serve as volunteer leaders. (Tr.

4997-99, 5121-22). This opinion was not, however, the result

of any actual experience in North Carolina; Stormer was a

native of Michigan who had not moved to North Carolina until

1976. (Tr. 4947, 4951). He based his view on his general

philosophy of human nature:

You know, if you go back to the Boston Tea Party,

people were told what they had to do and they did

not do it. Just by the fact you tell them you have

to do it, you create a certain amount of resistance

because people don't like to be told what they have

to do, especially by an agency of government. (Tr.

5121).

The only instances which Stormer knew about of actual resistance

to the integration of clubs were in the state of Texas prior

to 1976. (Tr. 4996-8).

Dr. Blalock, NCAES's director, offered a different reason

for continuing to provide services to single-race clubs. In

response to a question from the trial court as to the impact

of a court order requiring the integration of these clubs, he

did not assert such an order would fail or result in mass

resignations, but testified that its effectiveness would

depend, inter alia, on how many employees he could devote to

that task and on the number of minority members to be added

to each club. (Tr. 4413-15). Yet when asked if he could

16

insist that a 4-H club desegregate he replied "absolutely

not". (Tr. 4415)

We have no control over the volunteers. We have

no control over who goes to that club.... It is an

entirely voluntary effort. (Id.)

Blalock, however, had no doubts about the ability of the

NCAES to force these same clubs to accept any minority who

actually applied. (Tr. 4373). Although attendance at 4-H

camp, like memberships in the clubs, was also voluntary,

NCAES long ago successfully insisted that youth who wished to

attend do so on an integrated basis. (App. 950-53). In every

other area of official activity Blalock understood that he

could control the activities of a "voluntary" organization,

including 4-H and Homemaker clubs, by imposing conditions on

the receipt of state assistance; only when it came to integrat

ing those clubs did he insist the state was powerless to affect

the activities of such a group.

(2) The Applicable Legal Standards

The district court properly recognized that the Extension

Service was fully accountable for the membership practices

of the 4-H and Homemakers clubs. This Court long ago held

that organizations which receive significant public assistance

cannot engage in racial discrimination. Simkins v. Moses

Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F.2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963), cert.

denied 376 U.S. 938 (1964). In this case the federal and

state governments not only provided both printed materials

and professional training, instruction and guidance on the

part of the extension agents, but were in most instances

17

instrumental in creating the clubs in the first place. The

court below, however, concluded that neither the Constitution

nor Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act were violated so

long as the all-white clubs were not, as of the time of

trial, actually rejecting black applicants on the basis of

race. In the absence of proof of any such present dis

criminatory rejections, the court held that North Carolina

was free to continue to provide millions of dollars in

materials and services to the several thousand all-white

clubs at issue. (App. 94-102). Appellants maintain that the

decision below was erroneous as a matter of law.

First, a substantial number of the present single-race

clubs were established by North Carolina on a segregated basis

prior to 1965. Because of the longevity and low membership

turnover of the homemaker clubs, many if not most of the 1,690

intentionally segregated Homemaker clubs that existed in 1965

remain segregated today. The proportion of pre-1965 segregated

4-H clubs still in existence in 1982 may be somewhat lower.

The applicable Title VI regulations, 7 C.F.R. § 15.3

(b )(6)(i), provide:

In administering a program regarding which the recipient

has previously discriminated against persons on the

ground of race, color, or national origin, the recipient

must take affirmative action to overcome the effects

of prior discrimination. (emphasis added).

These regulations have the force of law and are entitled to

deference by the courts. Blacksher Res. Org. v. Housing

Authority of the City of Austin, 347 F. Supp. 1138, 1146-47

18

(W.D. Tex. 1972). Once clubs have been intentionally estab

lished by a state on a segregated basis, that initial act of

discrimination will, in the absence of affirmative action,

continue in effect. Individual members remain in the clubs

to which they were originally assigned on the basis of race;

there are doubtless significant numbers of members of Extension

Homemaker clubs today who are still in the clubs they joined

prior to 1965. Since a substantial proportion of new club

members are friends or relatives of existing members, such new

members will naturally be recruited in racial patterns that

mirror the initial act of intentional state discrimination.

Perhaps most importantly, when existing clubs are either all-

white or all-black, they are likely to stay that way because

prospective members, even if willing or perhaps anxious to

join integrated clubs, will be reluctant to be the only white

member of a black club, or vice versa. That is especially

probable where, as here, the state has given its apparent ap

proval of such racial separatism by establishing the segregated

clubs, servicing them on a racial basis until at least 1974,

and taking no steps to require or even encourage them to

integrate. The relatively unchanging number of all-white clubs

in North Carolina is dramatic proof of the extent to which

the effects of the intentional discrimination that existed in

1965 continue to control the membership patterns today.

The continued operation of clubs originally established

on a segregated basis violates the Fourteenth Amendment as

19

well. The state apparently believes that, having assigned

youth and homemakers on the basis of race prior to 1965, it

need only adopt a "freedom of choice" policy permitting

them, if they wish, to transfer to other clubs. This

practice doubtless has its origins in the freedom of choice

plans which were adopted by segregated school districts prior

to 1968 and which, like the freedom of choice plan adopted by

the NCAES, had virtually no impact on the racial composition

of existing segregated institutions. In 1968, however, the

Supreme Court unanimously struck down freedom of choice plans

where, as here, they had proved ineffective. Green v. School

Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

Brown II was a call for the dismantling of well-

trenched dual systems.... School boards then operating

state-compelled dual systems were ... clearly charged

with the affirmative duty to take whatever steps

might be necessary to convert to a unitary system

in which racial discrimination would be eliminated

root and branch .... The burden on a school board

today is to come forward with a plan that promises

realistically to work, and promises realistically

to work now .... [I]f [freedom of choice] fails to

undo segregation, other means must be used to achieve

this end.... The Board must be required to formulate

a new plan ... which promise[s] realistically to convert

promptly to a system without a "white" school and

a Negro" school, but just schools. 391 U.S. at 437.

These principles are equally applicable to desegregation of

a state-established dual 4-H and Extension Homemaker systems.

There is no serious claim in this case that North

Carolina has in fact succeeded in disestablishing the dual

system it required prior to 1965. The number of all-white

4-H clubs has declined only 8% during the 17 years since 1965.

The number of single-race 4-H clubs in integrated areas has

20

fallen by less than 2% since 1972. (App. 1807). A year after

this action was filed barely 1% of the Homemaker clubs in the

state were integrated; that deplorable pattern continues today

With regard to the ongoing establishment of single-race

clubs in mixed communities, NCAES does not claim that the

segregated nature of their membership is the result of "chance

Dr. Blalock conceded that the makeup of a particular club "is

determined by the local volunteer who has been recruited to

1 9 /serve as a leader of a club in that area. " — ' The state's

narrow prohibition against the discriminatory rejection of

black applicants is palpably insufficient to eliminate

present invidious discrimination. Discrimination in passing

on applications for membership is not the only or even the

most important method by which a club can be kept all-white.

The vast majority of new club members join because they are

individually recruited by club leaders or other members;

teaching those leaders how to attract members is regarded as

one of the most important functions of the extension agent.

(App. 939-940). Since most if not all members join as a

result of this word of mouth solicitation, discrimination in

recruitment will ordinarily be extraordinarily effective.

There is simply no need to reject black applicants if no

black is ever invited to apply.

Regardless of how the system of single-race clubs in

mixed communities came about, its very existence violates

19/ Deposition of January 30, 1973, p. 74.

21

Title VI per se. Title VI contemplates that minorities will

ordinarily be afforded a chance to participate in integrated

federally funded activities. In many North Carolina communi

ties today a black has no such opportunity. He or she is

forced to choose between joining an all-white program, as the

token and possibly ostracized non-white, or joining an

all-black program where his or her race will again be a

"badge of slavery." For a 10-year old black farm boy who

only wants to learn how to grow corn, or for a black housewife

who needs help getting by on a meager income, for ordinary

black women and children, the message of intolerance communi

cated by a club's all-white membership will turn them away as

effectively as the "Whites Only" signs of the past. The

price of admission is the courage and determination of James

Meredith or a Linda Brown; that price is too high.

The trial judge also upheld NCAES's refusal to require

clubs receiving state aid to actually integrate by asserting

that

in North Carolina as well as all other states integra

tion of the races more frequently than not meets with

strong resistance. The choice thus posed is whether

it is better that the Extension Service continue to

provide its much needed services to well over 100,000

North Carolina club members while striving to achieve

full integration of the clubs or that it withdraw such

services altogether as the government would have it do.

The Extension Service has opted for the former, and in so

doing this court does not perceive that it has violated

the rights of anyone under any law. (App. 101).

The judge's assertion that North Carolinians would forgo the

"much needed services" of the Extension Service rather than

participate in a club with members of another race is without

22

support in this record. A policy of requiring clubs to inte

grate as a condition of receiving state aid has not been tried

and failed in North Carolina; it has never been tried. Compul

sory integration of county and state-wide 4-H and Homemaker

activities, on the other hand, has been an unqualified success

For over a decade the members and leaders of all-white clubs

have voluntarily participated in these integrated programs,

evidently regarding their benefits as more important than

avoiding contact with blacks. There is little reason to

believe that the same youth and adults who today attend these

integrated activities would withdraw from their clubs merely

because they too were operated on an integrated basis.

The judge's apparent willingness to postpone still

further the integration of the 4-H and Extension Homemaker

programs because of outdated assumptions about the unwilling

ness of the public to obey the law of the land is sorely out

of place in 1982. North Carolina today is not the Little

Rock of 1958 or the Selma of 1965. Members of both races

now attend the same schools, ride on the same buses, eat at

the same restaurants, stay at the same hotels, and work on

an equal basis at the same jobs. It is not unreasonable to

ask or expect the men, women, boys and girls who have accepted

integration in most aspects of their lives to do so in the

4-H and Homemakers clubs that are organized and supported

with public funds. Eighteen years after the Supreme Court

held that the time for "all deliberate speed" had ended,— ^

20/ Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377

U.S. 218, 234 (1964).

23

further delay is intolerable.

II. THE DEFENDANTS DISCRIMINATED AGAINST BLACKS IN SALARIES

The named plaintiffs alleged, on behalf of themselves

and the purported class, that NCAES systematically discrimi

nated in the salaries it paid to blacks in comparison to these

paid whites holding the same position. The named plaintiffs

include employees hired both before and after 1965, the year

when the black and white branches of NCAES were merged. The

legal issues raised by these two groups are somewhat different,

and accordingly we discuss them separately.

(1) Pre-1965 Hires

The trial court properly recognized that salaries of

black professional employees prior to the merger were inten

tionally set lower than those of their white colleagues

holding the same positions. (App. 43, 77). The court noted

that the evidence of this systematic discrimination was

"undisputed". (App. 77). Dr. Blalock, who had worked for

NCAES prior to the merger and was its Director at the time of

the trial, candidly acknowledged that it was the policy of NCAES

to pay minority employees less than whites. He explained the

difference in the average wages of whites and blacks as:

... a reflection of what existed not only in North Caro

lina but throughout the country. At that point in time

...[black] home economics agents could be hired at a lower

salary than the white agents could [B]lack agricultural

agents could be hired and retained at a lower salary than

white agricultural agents. (App. 999).

One of the defendants' own exhibits demonstrated that before 1965

this difference between the salaries paid to blacks and whites

24

holding the same position was quite substantial. (App. 1625).

In 1965 the two branches of NCAES merged physically;

employees who had previously worked out of separate locations

were placed in the same office. But the salaries of black

employees, which prior to 1965 had been set at a lower level

because of their race, were not changed. None of NCAES's

written plans for compliance with the 1964 Civil Rights Act

contained any provisions for altering this discriminatory wage

structure.— ^ Although blacks were at least theoretically

eligible for the same across the board and merit raises as

whites, the base wage to which any raises were added, and thus

their aggregate salaries, remained for discriminatory reasons

lower than those of whites. In the absence of any steps to

alter it, the discriminatory wage scales established prior to

1965 simply remained in effect. Black employees hired before

that year might now work side by side with whites with identical

records, but they continued to be paid less than their white

colleagues simply because of their race.

The first efforts to disestablish this discriminatory

salary structure did not come until 1971, six years after the

purported "merger". In 1970 the average white salary was

higher than the average black salary for every category of

professional positions within NCAES. Black full agricultural

21/ DX 207; GX 115 (Revised Compliance Plans for Meeting

the Requirements of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; Cooperative

Extension Service State of North Carolina, Report on Status

of Compliance of State Extension Service Under Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, December 31, 1965; Letter

of George Hyatt, Jr. to Dr. Lloyd Davis, Sept. 15, 1965).

25

agents, the position held by the largest number of blacks

hired before 1965, averaged $432 a year less than whites in

the same job. (App. 1560).* This figure substantially understated

the actual disparity, since the average black agent had several

more years of seniority than the average white. Virtually all

of the named plaintiffs hired before 1965 earned less than the

average white in the same position.

1970 Wages

Job

Average

White Pre-1965

Average 22/ Plaintiff 23/ Difference

Agricultural Agent $10,871

Associate Agent 9,876

Assistant Agent 8,796

Home Economics Agent 9,893

$9,562

8,307

8,184

9,182

$1,309

1,569

612

711

In 1971, apparently as a result of prodding by federal

officials, Dr. Blalock, then assistant director in charge of

budget, proposed adjustments in the salaries of blacks

aimed at ending this discriminatory salary structure. A

memorandum prepared by him at the time noted three reasons

for the salary disparities:

[0]ur salaries for women and non-white men on average

are lower. Our figures verify. Due to several factors:

- The competitive market — This is not accept

able as a reason though.

- Tradition - not just in Ext[ension Service]

- Less County support for non-white positions.

(App. 1606).

22/ App. 1560.

23/ Appendix A.

- 26 -

At trial Blalock explained that by "competitive market" he

was referring to the fact that blacks because of their race

were less in demand than comparable whites. (App. 897-98).— /

Blalock urged in 1971 that action be taken "as quickly as

pos[sible] and preferably before our plan went into Washington"

(App. 1607), warning:

Obviously one of the areas where we'll be checked

is on salary. Easy to measure and at least see if

there appears to be any [disparity]. (App. 1605).

After reviewing figures from the Extension Service District

Chairmen, Blalock concluded that the needed increase in

black salary levels would be between $800 and $1100. (App.

1 608 ) .

Although the salary changes urged by Blalock might,

if fully implemented, have eliminated the salary disparities

caused by pre-1971 intentional discrimination, that did not

occur. The adjustments actually made in 1971 were far smaller

than the disparities found by Blalock. The gap between black

and white agricultural agents was reduced by only $85, while

the difference between black and white home economics agents

actually rose by $13 compared to 1970. Indeed, among the six

categories of professional employees, in three blacks actually

fell further behind their white colleagues between 1970 and

1971. (App. 1560). About a year and a half after these

24/ In his October 23, 1981 deposition Blalock reiterated re

garding the salary disparities in existence in 1970, "[T]he

organization had also been able to employ blacks at a lower

salary, again, because of the market demand and because of the

salary structure that we inherited when the two organizations

came together in the mid-sixties." p. 37.

27

salary adjustments the Extension Service made a detailed

analysis of the wages of full agents. It concluded that,

when full agents with comparable tenure and education were

compared, the salaries paid to blacks still averaged $455

less than those of whites. (App. 1610). The trial court

concluded that the 1971 adjustments had only "beg[u]n" the

elimination of the disparities rooted in earlier intentional

discrimination. (App. 77, 108).

Since 1972 virtually all pre-1965 blacks have been

employed as full agents. Although the salaries of black full

agents have risen slowly in comparison to those of whites,

throughout the last decade black agricultural agents have

consistently averaged five to six years of more tenure than

2 5/whites.— Even ignoring the differences in tenure, the

disparity in the wages of home economics and agricultural

agents did not end until 1974 and after 1976 respectively.— ^

Salary analyses offered at trial showed that on the average a

year of additional tenure for similar employees in the same

position was worth $50-56 in 1974,— ^ and $150-156 in 1981.—

Taking into consideration the additional salaries ordinarily

paid employees with more years of service, the disparity

between black and white wages in 1974 was still approximately

25/ App. 1562; GX 95; PX 50; PX 100; PX 98.

26/ See note 25, supra.

27/ GX 123, pp. 338-352. The size of the difference

depends on which other variables are considered.

28/ GX 122, pp. 30-57.

28

$750 for agricultural agents and $200 for home economics

agents. The disparity between black and white home economics

2 9/agents continued until 1979,— while the disparity between

black and white agricultural agents still has not clearly

been eliminated

In short the uncontradicted evidence showed, and the

trial court actually found, (1) that the wages of blacks

hired prior to 1965 were for discriminatory reasons set at

levels lower than those of whites in the same position, (2)

that no steps to eliminate those discriminatory wage levels

were taken until 1971, and (3) that the 1971 adjustments

were insufficient to fully achieve that result. The dispari

ties which existed before and after the 1971 adjustments

continued until at least 1976. The lower court recognized

that the limitations period applicable to the claim of uncon

stitutional racial discrimination began in 1968. (App. 64,

n.20). The government was also entitled to seek back pay for

employment discrimination in or after that year, since such

discrimination violated USDA equal employment regulations

issued in August, 1968. 7 CFR §§ 18.1-18.9. These facts

constitute an actionable violation of the constitution, 42

U.S.C. § 1981, the USDA regulations and, after March 1972,

Title VII; the only possible area of dispute is not whether

29/ In 1979 blacks had .35 years more seniority than whites,

but earned $94 a year less. See note 25, supra.

30/ In 1981 blacks had 5.9 years more experience than whites,

which should have been worth over $850 a year in wages; in

fact they earned only $707 a year more. See note 25, supra.

29

that unlawful discrimination existed, but when, if ever, the

defendants brought it to an end. The burden of proving that

that discrimination had ended was on the defendants. Evans v .

Harnett County Bd. of Ed., 684 F.2d 304, 307 (4th Cir. 1982).

Yet the trial court inexplicably denied all relief.

The trial court's error appears to derive from its pre

occupation with the narrow question of whether there was still

intentional discrimination in 1981. The court dismissed a

government comparison of salaries earned by similar employees

in January 1973 on the ground that it involved differences

that existed "almost ten years ago," although this was over

4 years after the commencement of the limitations period.

(App. 78) Much of the court's opinion is devoted to regression

analyses of employee salaries between 1974 and 1981 (App.

75-77, 80-86). After noting that the statistical evidence

appeared to establish a prima facie case of discrimination,

App. 78, 80, 87), the trial judge concluded it was rebutted

by defense evidence concerning the years 1976 through 1981.

(App. 87-88). The trial court's ultimate conclusion that the

defendants had explained the "seeming salary disparities"

clearly refers only to the disparities in the regression

analyses for 1974-1981. That conclusion is clearly erroneous,

but even if it were correct those regression analyses cover

only the period after 1973. In sum, having held that the

salary disparities which existed before and after 1971 were

the result of intentional discrimination, and that the

plaintiffs would be entitled to back pay for salary discrimi-

30

nation in or after 1968, the trial court never clearly

resolved the defendants' liability for years prior to 1974,

and simply disregarded those holdings in assessing the

evidence of salary disparities after 1974.

The trial court's apparent indifference to its own findings

of discrimination based disparities prior to 1974 may also

have been the result of its sympathy for a supposed "problem"

faced by NCAES in obeying federal law.

The Extension Service's problem of bringing black

and white salaries into line has been similar to that

which faced most business enterprises with a prior

history of racial discrimination following the passage

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Just as it had been

found in the area of education that there is no such

thing as instant integration, it was soon found in

the field of business and industry that there is no

such thing as instant equality in employment. Without

risking serious disruption of a business by prohibitively

costly budgetary alterations and a possible practice

of wholesale reverse discrimination it was soon recog

nized (though not always by the courts) that the adjust

ments mandated by the law simply could not be made over

night. The dilemma of the Extension Service was further

compounded by the fact that its operating funds come from

three separate political entities each of which retains a

voice in all major employment decisions. (App. 77)

This passage is without foundation in this record or American

experience. This statement literally means that, where an

employer prior to 1965 was paying blacks less than whites, it

would have been "prohibitively costly" and "wholesale reverse

discrimination" to equalize those salaries when the 1964

Civil Rights Act became effective on July 1, 1965 or when the

Title VII amendments became effective in March, 1972. These

purported burdens apparently justified in the trial judge's

mind continuing such intentionally discriminatory salary

31

disparities for some time after the letter of the law required

their elimination. In the case of the Extension Service, this

period of grace seems to have to have extended until at least

1976. Other portions of the district court opinion suggest that

NCAES, having prior to 1965 intentionally set the base salaries

of blacks lower than those of whites, could continue to pay

blacks hired prior to that date less than whites for the rest

of their natural lives. (App. 91-93).

Nothing in the decisions of this or any other court

sanctions paying blacks less than whites as a cost saving

measure, or warrants characterizing as "reverse discrimination"

the simple act of paying blacks and whites the same salary

for the same work. We know of no basis, and none can readily

be imagined, for asserting that business found there was a

"problem" or "dilemma" in paying equal wages for equal work

as soon as the law required it. The NCAES never asserted that

it would have ben impossible or even difficult to eliminate

in 1971, 1965, or earlier the wage disparities rooted in the

segregationist policies of its past. Tolerance of con4-in,ied

salary discrimination on the part of state or county officials

to after 1965 is particularly unjustifiable, for their obliga

tion to avoid such discrimination does not date from the enact

ment of the 1964 Civil Rights Act or the 1972 amendments, but

from the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment over a century

ago. No authoritative federal decision, not even Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1895), sanctioned discrimination on the

32

basis of race in fixing the wages of government employees.

(2) Post-1965 Hires

Although the salaries of black employees hired prior to

1965 were established during a period when the Extension

Service had an avowed policy of discrimination, that is not

true of blacks hired after 1965. Both the initial salaries

and subsequent raises of post-1965 hires were fixed during an

era when the NCAES had at least a nominal policy of non-discrim

ination. For pre-1965 hires the critical issue is when, if

ever, the admittedly discriminatory wage disparities were

ended; for post-1965 hires the issue is whether such purposeful

disparities existed at all. The vast majority of the pre-1965

hires were already full agents by 1971;— / thus the treatment

of blacks hired since 1965 that year can readily be traced by

by examining the salaries of assistant and associate agents.

State NCAES officials establish a minimum salary for

newly hired assistant agents although particular individuals

may at times be paid more. Since employees typically remain

at the assistant agent level only a few years, the cumulative

effect of any disparity in raises would likely be small.

Prior to 1974 the salaries of assistant agents were consistently

higher for whites than for blacks; the difference varied from

$56 for assistant home economics agents in 1970 to $621

32/for assistant agricultural agents in 1971.— All of the

31/ See Appendix A.

32/ See note 25, supra. Data for 1971 and 1972 can be found

at App. 1560.

33

n*med plaintiffs hired since 1965 who were assistant agents

in 1970 were making less than the average white in these

positions. Appendix B. Since 1975 average white salaries

have exceeded average black salaries about as often as the

opposite was the case.

The situation of associate agents presents a far greater

opportunity for discrimination than does that of assistant

agents. The average black associate agent has been in that

position for 5 or 6 years;— ^ any consistent discrimination

in raises over that longer period of time would result in a no

ticeable difference in total salary. The record in this case

demonstrated that that is precisely what has occurred:

Associate Home Economics Agents

Salaries 1970-81 34/

Average Average Average Average Difference

White White Black Black in YearYear Salary Tenure Salary Tenure Average Wage

1970 $ 8553 $ 8,195 $358

1971 $ 9146 $ 9,040 $106

1973 $ 9503 4.7 $ 9,421 5.0 $ 82

1974 $ 9683 4 $ 9,589 6 $ 94

1976 $11,879 5.03 $11,677 5.82 $202

1979 $14,087 5.29 $13,929 5.71 158

1980 $14,473 4.8 $14,051 5.1 442

1981 $16,643 6.5 $16,232 6.5 411

33/ App. 1562; GX 95; PX 48, 50, 98, 100.

34/ See n. 25, supra. The data for 1976-80 is for employees

with bachelor degrees. The exhibits do not contain average ten

ure data for 1970 and 1971.

34

Associate Agricultural Agents

Salaries 1970-81 35/

Average Average Average Average DifferenceWhite White Black Black inYear Salary Tenure Average Tenure Average Waqe

1970 $ 9,876 $ 8,956 $ 9201971 10,240 9,558 682

1973 10,292 3.6 9,797 5.6 4951974 10,244 3 9,840 6 4041976 12,711 4.55 11,885 5.43 8261979 14,754 4.55 13,518 6.00 1,2361980 15,253 4.3 14,485 5.3 7681981 17,035 5.2 15,849 6.7 1,186

The wages of white associate agents have exceeded those of

black associate agents in every year, for both home economics

and agricultural agents, despite the fact that in every year— ^

for which the data is available average black tenure exceeded

average white tenure.

Blalock's 1971 description of the forms of discrimination

behind then existing wage patterns, and his estimate of the re

sulting disparities in income, are not limited to pre-1965 hires

or policies. His 1971 memorandum referred to the treatment of

all black employees, and to then present rather than merely his

torical discriminatory practices. Blalock knew the 1970 salary

disparity between black and white associates agents was actually

greater than that between black and white full agents, for the

adjustments implemented at his insistence were larger for asso

ciate agents than for those for full agents. (App. 1560).

35/ See n. 25, supra.

36/ Except for 1981 associate home economics agents, whose

average tenure was equal.

35

After 1971, however, although the salary disparity for full

agents eventually declined, that for associate agents actually

increased. Thus in 1981, when black full agricultural agents

earned more than white agents, black associate agricultural

agents earned $1,186 less than white associate agents.

The decision of the court below contains no consideration

of these specific salary differences in the wages of associate

and, prior to 1974, assistant agents. It considered only the

general salary studies, "regression analyses", conducted by

experts for the government and the defense. Utilizing standard

and essentially identical statistical methods, the two experts

calculated the average salary difference between blacks and

whites with the same position, education, tenure, and sex. The

results of their calculations were quite similar:

Salary Disparities:

Average Amount by Which White Salary

Exceeded That of Blacks With Same

Position, Education, Tenure and Sex

Year

1974

1975

1981

Government 3 7 , Defense 3Q ,

Regression Analysis— / Regression Analysis— /

$257-337

312-395

158-248

$364-381

384-391

310-415

Although these calculations of the average disparities within

37/ App. 399-418, 1568, 1601; GX 123 at 289, 297, 310 (1974),

GX 124 at 33, 39, 48, 60 (1975); GX 122 at 37, 46, 55 (1981).

Differences in each year depend on which other variables are

considered.

38/ App. 1681, 1693-1715. Differences in each year depend

on which other varibales are con~idered. These figures do not

include adjustments for quartile ratings, which are discussed

below at p. 48.

36

all positions provide a less detailed picture than the above

analysis of the disparities in particular jobs, the results

are entirely consistent.

The trial court recognized that the government's statis

tical analysis "unquestionably establishes salary disparities"

(App. 77) which were sufficient to establish a prima facie case

of intentional discrimination. (App. 80, 87). In fact these

salary disparities proved considerably more than a mere prima

facie case. If plaintiffs in an ordinary Title VII case were

to calculate the company-wide average wages of blacks and

whites, any resulting difference might be entitled to limited

weight; where the different positions averaged together in

volve entirely unrelated skills and educational requirements,

ranging from custodians to lawyers and accountants, disparities

in average wages could be caused by differences in the jobs to

which, possibly on the basis of their qualifications, employees

may be assigned. But in the instant case the salary compari

son is of blacks and whites wiht the same tenure and education

holding the identical position, precisely the comparison called

for in E.E.O.C. v. Federal Reserve Bank, ___ F.2d ___ (4th Cir.

1983) (slip opinion, pp. 61, 63). There is ordinarily a strong

presumption that blacks and whites in the same position will re

ceive the same salary. The employer itself often has, in

deciding to hire or promote individuals into a particular job,

determined that they have roughly comparable skills. While

there may be some differences between particular individuals,

37

it is unlikely that there will be any significant relevant dif

ferences in qualification between blacks and whites as a group

hired by the same employer in the same era for the same job.

The trial court, however, chose to disregard these striking

salary disparities because it believed the plaintiffs had not

eliminated every possible legitimate explanation for them:

[B]ecause of their failure to include many of the vital

factors to be considered in fixing salaries the probative

force of these statistics has been so substantially under

mined that they cannot sustain a finding of purposeful

discrimination .... (App. 87-88)

The lower court conceded that the plaintiffs had established

that neither tenure nor education could explain why blacks

were being paid less than whites for doing the same job, but ar

gued that there were at least nine other possible explanations,

and insisted that the plaintiffs had failed to show that these

were not behind the d i s p a r i t i e s /

39/ "(1) Performance of agents measured against the agents'

plan of work;

(2) The variations in salaries created by across the

board state raises with the different percentage of

state contributions in each county;

(3) The across the board increases in agent salaries

by some counties and not in others;

(4) The merit raises provided by the state;

(5) The merit raises provided for by the counties in

which Extension Service personnel have no input;

(6) The merit raises provided by the counties with

limited or full participation in the merit re

commendation by Extension Service personnel;

(7) The range in merit salary increases provided by

the counties (0 to 12% in 1981);

38

This contention misconceives the burden of proof on a

plaintiff alleging intentional racial discrimination. No

plaintiff is required to prove groundless every defense that

could be conceived of by the court or a defendant's attorney.

A prima facie case is "prima facie" because it is sufficient,

not to satisfy this unmeetable burden, but to shift to the de

fendant the responsibility of coming forward with evidence de

monstrating that the proven disparities were not the result of

discrimination. See Chisholm v. United States Postal Service,

665 F.2d 482, 496 (4th Cir. 1981). Here the plaintiffs not only

showed pronounced disparities in the salaries paid to blacks and

whites in the same position, evidence sufficient by itself to

establish a strong prima facie case, but went further and elim

inated by uncontradicted evidence the possibility that these

disparities could be exolained by differences in education or

tenure. At that juncture the burden was on the defendant to

offer credible evidence that the disparities were the result

of some specific legitimate non-discriminatory circumstance.

The defendant, however, did not do so; it responded by insist

ing that such defenses could still be imagined and that the

plaintiff had not disproved them. This was insufficient as a

matter of law. No matter how strong a plaintiff's case, it

(8) Prior and relevant experience; and

(9) Variations in salary due to market demands both

at time of hire and later for agents with skills

in short supply or prior experience."

(App. 81-82).

39

will always be possible to imagine some facts which, if true,

would establish the defendant's innocence. It is possible,

for example, that some of the higher paid whites had won the

Nobel Prize in biology, or that blacks were rejecting raises

because they felt that NCAES needed the money for other things.

But neither these nor any of the nine other possible explana

tions mentioned in the court's opinion were substantiated by

defense evidence.— ^

The court also concluded that this evidence of salary

discrimination had been rebutted by "defendants' explanatory

evidence". (App. 78). It relied primarily on Defendants'

Exhibits 201-205, (App. 2227-31) which it summarized as follows

In 1976, when the salaries of all agents except county

chairmen were compared, the average salary of white

agents exceeded that of black agents by $130, but the

average tenure of white agents exceeded that of black

agents by 1.5 years.

In the same year the salaries of black agents with a

bachelor's degree exceeded that of white agents with the

same degree by $121 although the average tenure of the

white agents exceeded that of the black agents by 1.6

years. . . . The figures for 1979, 1980 and 1981 showed

comparable results. . . . (App. 86-87)

The defendants' assertion, heavily relied on by the court, that

blacks had less average tenure than whites in 1976 is simply

false. The critical error is contained in DX 201 (App. 2227),

40/ Job performance ratings, listed by the trial judge as one

possible reason why blacks were paid less, revealed that in

1975 the ratings of blacks were actually higher than those of

whites. App. 1716, analyses 5 and 6. The disparity between

the wages of comparable blacks and whites in the same job was

$384; when blacks and whites with comparable quartile ratings

were considered, the disparity was $475. In 1981, on the other

hand, the salary disparity was lower when quartile ratings were

considered. App. 1691, analyses 5 and 6.

40

which states that the average tenure in 1976 of blacks (other

than chairmen) with a bachelor's degree was 7.7 years; an ex

amination of the more detailed figures in PX 48 shows that the

actual average black tenure is 12.6 years. Thus in 1976 all

blacks and blacks with bachelor degree had 3 years more tenure

than whites, precisely the opposite of the court's assumption.

The court's assertion that the 1979, 1980, and 1981 figures are

"comparable" to its description of the 1976 data is, with regard

to tenure, also inaccurate. In all of those years blacks in

every category had more tenure than whites. (App. 2228-31).

These defense exhibits, moreover simply do not provide

a meaningful basis for determining whether there is discrimi

nation in the salaries paid to employees in the same job.

The exhibits were prepared by deliberately omitting the 96-99

4 1/best paid white employees — those serving as state chairmen. — '

Such artfully constructed "averages" are insufficient to rebut

specific and otherwise unexplained disparities in the salaries

of blacks and whites in particular jobs.

(3) The Individual Claims

Approximately a month after its decision rejecting the

pattern and practice and class claims, the district court

handed down a second opinion regarding the salary discrimin-

42/ation claims of the named plaintiffs.— 7 (App. 115-161).

£1/ App. 2227-31.

42/ The claims of some plaintiffs were dismissed in an order

dated August 20, 1982, the same date as the order regarding

the class claims. (App. 111-112).

41

The court expressly recognized that, had the private and

government plaintiffs been upheld in its earlier decision,

even blacks who were not named plaintiffs "would have been

entitled to relief as members of the class." (App. 115, n.1).

The court's analysis of those individual claims was made

against the background of its erroneous assumption that NCAES

had not engaged in systematic salary discrimination. As we

demonstrated above, the undisputed evidence in the record,

and in certain instances the court's own findings, compel the

conclusion that the lower salaries paid to blacks by the de

fendants were the result of a pattern of racial discrimination.

That conclusion requires the reversal of the lower court's

disposition of the individual claims. Sledge v. J.P. Stevens

Co., Inc., 585 F.2d 625, 637-38 (4th Cir. 1978). The named

plaintiffs, like all other black employees, are entitled to

relief as members of the group discriminated against by the

Extension Service.

The trial court's resolution of the individual claims was

also tainted by several other errors. In rejecting most of the

claims the court below expressly insisted that proof that a

black was being paid less than comparable whites was insufficient

. . . 43/to make out a prima facie case of discrimination.— The claims

of sixteen plaintiffs were dismissed with a single sentence:

On behalf of these plaintiffs exhibits were

offered showing salary comparisons between them

43/ App. 78, 112, 126, 127, 130, 133, 137, 138, 142, 143, 145,

154, 156, 158.

42

and certain white employees, but there was no

evidence to show the relative qualifications and

job performances of these plaintiffs and those

of the persons with whom they were sought to be

compared, and this evidence standing alone was

not sufficient to create a prima facie case of

discrimination. (App. 112).

The trial judge asserted that in the absence of proof by a

plaintiff that "any disparity was predicated on race rather

than performance. . . it would be sheer speculation to find

otherwise." (App. 130). This is the precise opposite of the

allocation of burden of proof approved by this court in

Chisholm v. United States Postal Service, 665 F.2d 482, 496

(4th Cir. 1981) .

We urge that, as in its analysis of the difference in

average black and white salaries, the trial judge erred as a

matter of law and misallocated the burden of producing evi

dence. This is not a case in which plaintiffs sought to com

pare the salary of the Director of the Extension Service with

that of a secretary, or simply relied on disparities between,

for example, the wages of a custodian and a nuclear physicist

employed by the same firm. The evidence adduced by plaintiffs

showed that the black named plaintiffs were earning less than

whites who held the same position and whose education and ten

ure were either less than or no better than equal to that of

the plaintiffs. Such evidence is sufficient to place on the

defendants the burden of adducing credible evidence that this

disparity was not the result of unlawful discrimination. The

43

plaintiffs were not required to anticipate and disprove every

possible explanation for such disparities. The defendants were

in possession of the employment records of all the employees

involved in these comparisons, and, where a legitimate reason

had existed for a particular disparity, they could readily have

proved it. In some instances the defendants attempted to ad

duce evidence of this kind, but in others they did not. In