City of Danville, VA School Board v. Medley Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Danville, VA School Board v. Medley Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1973. 72158f6f-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/99538235-5637-42ef-a05c-92e0f6b4e5b2/city-of-danville-va-school-board-v-medley-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

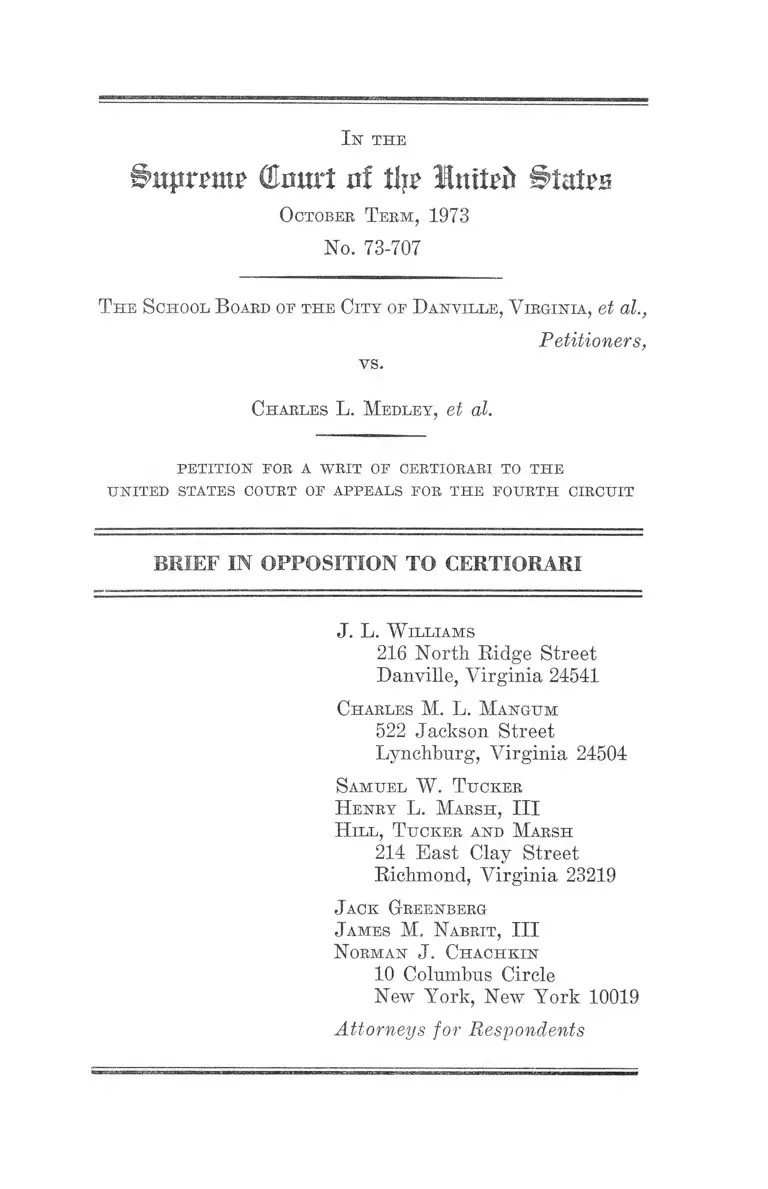

I n th e

©curt nf % llniUb States

O ctober T erm , 1973

No. 73-707

T h e S chool B oard of th e C it y of D an ville , V irgin ia , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

Charles L. M edley, et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

J. L. W illiam s

216 North Ridge Street

Danville, Virginia 24541

Charles M. L. M angum

522 Jackson Street

Lynchburg, Virginia 24504

S am uel W. T ucker

H en ry L. M arsh , III

H il l , T u cker and M arsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

N orman J. Ch a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

I n th e

kapron? (tort nt tty States

O ctober T erm , 1973

No. 73-707

T h e S chool B oard oe th e Cit y of D an ville , V irgin ia , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

Charles L. M edley, et at.

petition for a w rit of certiorari to th e

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Opinions Below

The August 3, 1973 opinion of the Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit, and the concurring and dissenting

opinion of Judge Winter, are now reported at 482 F.2d

1061.

Question Presented

Did the Court of Appeals or the district court err in

requiring Danville to devise and implement an effective

pupil desegregation plan including reassignment of ele

mentary school students across the Dan River, with trans

portation as necessary, since the geographic zoning plan

adopted by the school district in 1970 had left many schools

in this small system with racial compositions which were

substantially disproportionate to that of the entire district ?

2

Reasons Why the Writ Should Be Denied

This is a startlingly simple case. It involves a small

school district divided by the Dan River and a federal

district court, both of which (despite this Court’s decisions

in Swann1 and Davis2) sought to characterize demands for

effective school desegregation as efforts to achieve “racial

balance,” and to make the river an impassable barrier to

constitutional elementary school integration. The United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which in

the past has been sharply divided on many school desegre

gation issues,3 was unanimous in this case4 in requiring that

Danville at long last complete the process of desegregating

its schools.

The Danville School Board’s attempt to create serious

constitutional issues where there are none must fail. This

case involves a historically dual system, like Charlotte, and

the issue presented to both the district court and the Court

of Appeals w as: has Danville taken effective measures to

eliminate its former mandated segregation and the effects

thereof? Cf. Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968). The district court agreed

that, when the case first came before it in 1971, schools of

substantially disproportionate racial composition (when

compared to the system-wide distribution of black and

1 Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of E duc , 402 U S 1

(1971).

2 Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs of Mobile, 402 U S 33

(1971).

3 See, e.g., Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 431

F.2d 138 (1970), rev’d in part, 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Council of the

City of Emporia v. Wright, 442 F.2d 570, 588 (1971), rev’d 407

U.S. 451 (1972).

4 The partial dissenting opinion of Judge Winter did not concern

the issue of student assignment.

3

white students) remained despite the availability of reme

dial measures to eliminate them. The district court ac

cordingly required creation of 5-6 grade centers on either

side of the Dan River.

However, the district court stopped short of completely

eliminating disproportionate schools by assigning ele

mentary students across the Dan River (despite the fact

that some schools of differing racial composition on either

side of the river were closer to each other than to other

facilities on the same shore [Ptn. App. 59a]). That court

noted the crowded bridges, some without sidewalks, and de

termined it could not subject elementary children to these

“hazards.” In reversing, the Court of Appeals considered

the distances involved [Ptn. App. 59a] and concluded that

highway hazards could be minimized by providing pupil

transportation [id. at 60a]; in any event, the Court held,

there were not “ specific findings which demonstrate that

no other plan affording greater integration is practicable”

[id. at 59a, citing Thompson v. School Bd. of Newport News,

465 F.2d 83 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 413 U.S. 920

(1973)], and the case was remanded for further proceed

ings.

The Court of Appeals’ decision is eminently sound. The

Board’s claim that review here is merited can be made only

by totally ignoring this Court’s language in Swann:

The district judge or school authorities should make

every effort to achieve the greatest possible degree of

actual desegregation and will thus necessarily be con

cerned with the elimination of one-race schools. No

per se rule can adequately embrace all the difficulties

of reconciling the competing interests involved; but in

a system with a history of segregation the need for

remedial criteria of sufficient specificity to assure a

4

school authority’s compliance with its, constitutional

duty warrants a presumption against schools that are

substantially disproportionate in their racial composi

tion.

402 U.S., at 26. That is precisely the gravamen of the

Court of Appeals’ decision.

It is true that the decision below conflicts with the ap

proach of the Sixth Circuit in Goss v. Board of Educ. of

Knoxville, 482 F.2d 1044 (1973). The conflict was noted by

petitioners Goss, et al. (represented by some of the same

counsel who represent the respondents in Danville) in

their Petition for Writ of Certiorari (No. 73-661), presently

pending before this Court. As noted therein, the Sixth

Circuit (like the district court in Danville) seems to place

little weight upon the language of this Court in Swann,

quoted above. Its approval of continuing substantial seg

regation in Knoxville because the district court thought

the plaintiffs wanted racial balance, or because of presumed

impracticalities, cannot be squared with this Court’s con

trolling decisions. While the disparate approaches of the

two Circuits constitutes a situation ripe for correction by

this Court’s certiorari jurisdiction, we submit that the facts

and dispositions of the two cases compel the conclusion

that the Sixth Circuit’s decision is the erroneous one.

Full and appropriate relief as well as clarification of the

law can be satisfactorily achieved by reviewing Goss and

denying the writ in this Danville case.

5

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, respondents re

spectfully pray that the Writ be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

J. L. W illiam s

216 North Ridge Street

Danville, Virginia 24541

C harles M. L. M angum

522 Jackson Street

Lynchburg, Virginia 24504

S am uel W. T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , III

H il l , T ucker and M arsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

J ack Greenberg

J ames M . N abrit, III

N orman J . Ch a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219