Parker v. Lewis Reply Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Parker v. Lewis Reply Brief for Appellant, 1981. 04fbfd8d-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/99997a01-cf4d-49ad-87ab-7e4bf9fd9525/parker-v-lewis-reply-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

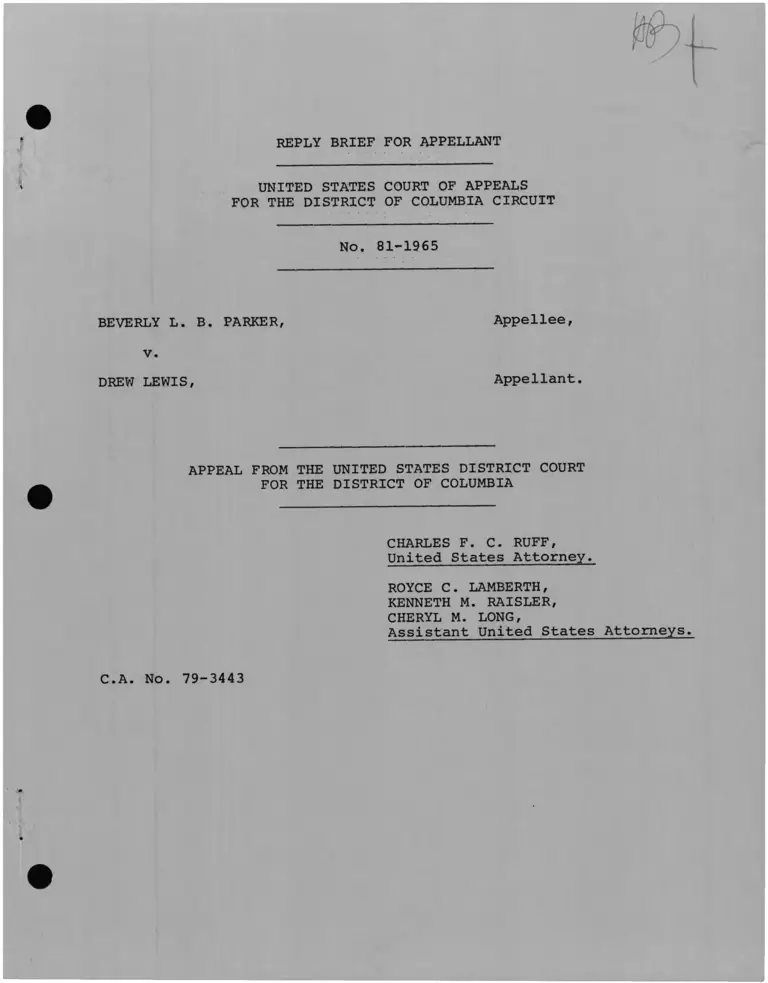

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 81-1965

BEVERLY L. B. PARKER, Appellee,

v.

DREW LEWIS, Appellant.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

CHARLES F. C. RUFF,United States Attorney.

ROYCE C. LAMBERTH,

KENNETH M. RAISLER,

CHERYL M. LONG,Assistant United States Attorneys.

C .A. No. 79-3443

I N D E X

Page

ARGUMENT ................................................ 1

I. The District Court's failure to permit discovery

and a hearing is an abuse of discretion . . . . 1

II. The District Court abused its discretion when

it awarded counsel for appellee's compensation

at the high hourly rates that they sought . . . 3

CONCLUSION................................................ 6

TABLE OF CASES AND AUTHORITIES

*Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880 (D.C. Cir. 1980)

(en banc) (Copela~n~d III) .............................. passim

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d 714

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ......................................... 2

Equal Access to Justice Act, 28 U.S.C. §2412 (1980) . . . 6

*Case chiefly relied upon is marked with an asterisk.

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 81-1965

BEVERLY L. B. PARKER,

v.

DREW LEWIS,

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court's Failure To Permit

Discovery And A Hearing Is An Abuse Of

Discretion. ___________________

In attempting to argue that the District Court did not abuse

its discretion in denying discovery and a hearing, counsel for

appellee asserts that there was no factual dispute between the

parties because appellant did not contradict facts set out by plain

tiff in its submissions. Counsel also argues that any discovery

proposed by appellant would have been unnecessary. Inherent in this

Appellee,

Appellant.

2

and appellee's other arguments is the unwarranted assumption that

appellant must introduce evidence proving that counsel for appellee

are not entitled to whatever attorneys' fees they seek from the

District Court. In reality, it is clear that "plaintiff has the

burden of proving his entitlement to an award of attorney's fees

just as he would bear the burden of proving a claim for any other

money judgment." Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488

F.2d 714, 720 (5th Cir. 1974). Accord, Copeland v. Marshall, 641

F.2d 880, 891, 892 (D.C. Cir. 1980) (en banc) (Copeland III).

Therefore appellant pointed out to the District Court that counsel

for appellee had not proved entitlement to the amount sought and

that the District Court should either deny counsel for appellee's

request or require them to submit more evidence justifying it.

Alternatively, appellant sought the opportunity to take discovery

and to probe appellee's assertions in a hearing.

Discovery and a hearing would have been helpful to appellant

and the Court because appellant challenged the inadequately

documented, duplicious hours spent in conferences between counsel

for appellee. Discovery would also, among other things, have

helped determine what the market rate is for counsel for appellee

based in part on what they have been paid in the past by their

paying clients.

1/ This Court specifically recognized that the Johnson analysis

"remain[s ] central to any fee award." Copeland III, supra at 889.

3

II. The District Court Abused Its Discretion

When It Awarded Counsel For Appellee's

Compensation At The High Hourly Rates

That They Sought._________________________

Counsel for appellee's initial argument in asserting that

they are entitled to up to $138 per hour is to attempt to change

the focus of this appeal from whether they have adequately justified

that hourly rate to the United States Attorney's settlement

policy on attorneys' fees. The issue before this Court is not

U.S. Attorney's office's settlement policy but whether counsel

for appellee have justified the rate that they seek as the market

rate. Counsel for appellant did inform the District Court of the

United States Attorney's then current hourly settlement rates — ^

because those rates more realistically reflect the "market rates"

for Title VII actions in this area as well as more closely approxi

mate awards by the District Courts then those proposed by counsel

for appellee. (See Appellant's Appendix A to his initial brief).

As previously stated, the issue before this Court is also not whether

appellant has disproven counsel for appellee's entitlement to a

2/ The United States Attorney's settlement rates are now $75 per

hour for attorneys with seven or more years experience; $60 per

hour for those with from five to seven years experience; and $45

for those with less than five years experience.

(

particular hourly rate. Rather counsel for appellee must prove

that the rates they seek up to $138 per hour are the market rates

in this area for similar work.

Arguing that the rates awarded in this case were appropriate,

appellee seriously misstates several contentions of appellant and

continues to evade the central issue in this appeal.

On page thirteen of her brief, appellee erroneously states

that appellant's position in the District Court "was that awards

in other cases were essentially irrelevant." What we did argue

was that the District Court should ignore those cases cited by

appellee which were obviously not Title VII cases or which lacked

enough descriptive detail to make profitable comparison possible.

See Brief of Appellant at 11-12. The logic of our position is

self-evident in light of Copeland Ill's mandate to the District

Court that market rates reflect prevailing hourly rates in this

particular legal community for the particular kind of litigation.

On page fifteen of her brief, appellee likewise argues

erroneously that appellant's "alternative argument," is "that the

4

3/ Contrary to appellee's assertion in footnote 7 of her brief,

we have not "abandoned" our position that such cases are improperly

used in calculating the lodestar. We included, in the appendix to

our brief, a list of a wide range of fee awards only for the purpose

of showing how far beyond the norm in this area appellee's rates are

even when compared to more sophisticated litigation, such as antitrust

cases.

5

'market' is determined solely by what plaintiff's counsel's

clients pay. . Nowhere has appellant ever espoused the position

that present hourly rates under a Copeland III analysis can or

should be derived solely by reference to the rates paid to the

individual plaintiff's attorney. Quite to the contrary, appellant

clearly set forth in its brief to this Court that the market rate

should be calculated in light of several factors, including

evidence presented by the plaintiff of the actual hourly rates

being paid to her own attorneys by other clients or rates actually

paid to other local Title VII lawyers for similar services. See

Brief of Appellant at 8. This Court, in Copeland III, recognized

that "hourly rates used in the 'lodestar' represent the prevailing

rate for clients who typically pay their bills promptly." Iji. at

893. In the clearest language, this Court requires that a proper

fee analysis include proof of what is actually paid in the local

Title VII legal marketplace, not merely what is charged or levied

by a District Court. — ^

On pages sixteen and seventeen of her brief, appellee seems

to suggest that appellant is urging this Court to regard the

$75.00 per hour maximum rate prescribed in the Equal Access to

57 Discovery would have revealed the extent to which the rates

demanded by appellee's counsel had any relationship to rates

actually paid in this community and whether counsel even attempted

to account for such payments to fellow members of the bar in formu

lating their basic fees, irrespective of the supposed inflation boosting factor.

6

Justice Act, 28 U.S.C. §2412 (1980), as the enforceable limit on

fees in the instant action. We cite that statute in our brief

for the purpose of illustrating that the Congress of the United

States had determined that $75.00 per hour is a reasonable rate

for attorney's in 1981. As a practical matter, many of the cases

involving fees assessed against the United States will be litigated

in this jurisdiction. We explicitly state in our brief that the

Act does not place a limit upon fees in Title VII cases. See

Brief for Appellant at 10. However, we invited the Court's

attention to the Act because it is yet another factor showing how

the unusually high rates awarded in this case compare to what is

considered reasonable.

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, for the reasons stated herein and in our main

brief, appellant respectfully submits that the judgment of the

District Court should be reversed and the case remanded to the

District Court with directions to permit discovery and a hearing

and to reconsider the fee award using the appropriate Copeland III

factors.

CHARLES F. C. RUFF,

United States Attorney.

ROYCE C. LAMBERTH,

KENNETH M. RAISLER,

CHERYL M. LONG,

Assitant United States Attorneys.