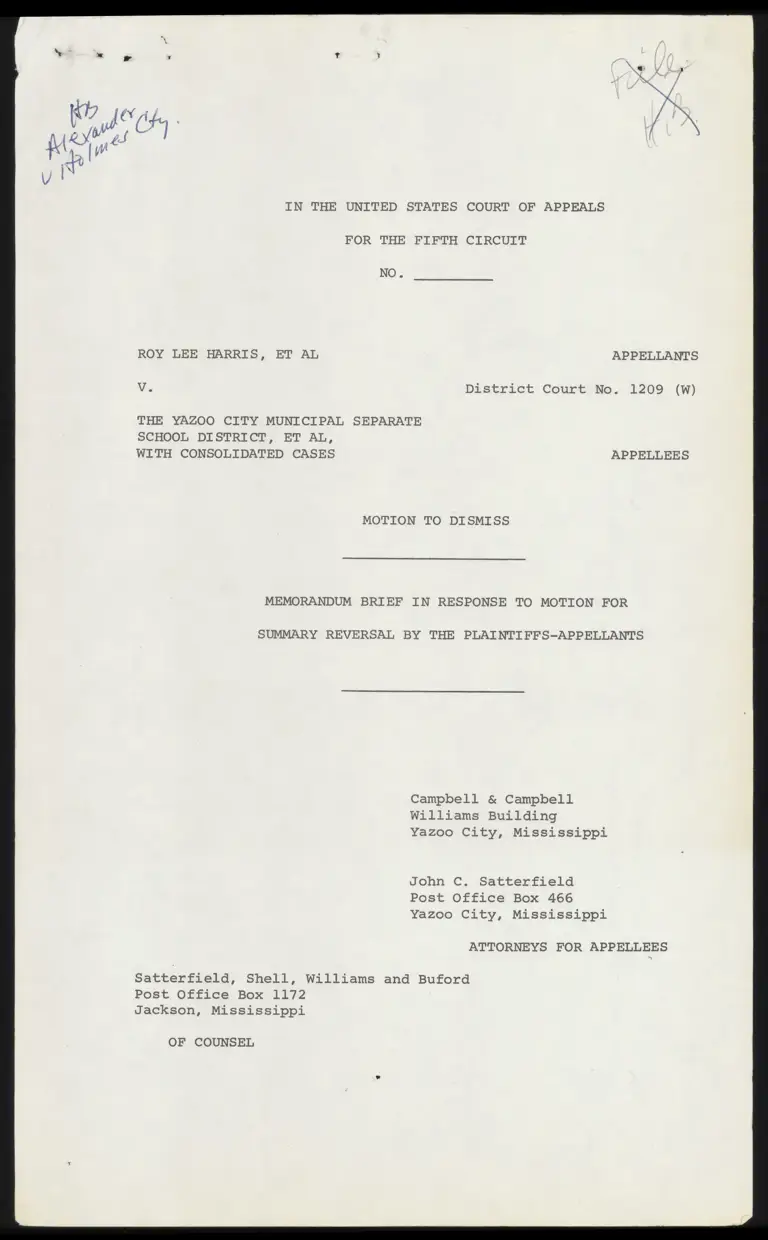

Memorandum Brief in Response to Motion for Summary Reversal by the Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

June 19, 1969

34 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Memorandum Brief in Response to Motion for Summary Reversal by the Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1969. f7611e24-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/99e7b6d7-e0bc-4ab2-83b1-fa2595dd9ff7/memorandum-brief-in-response-to-motion-for-summary-reversal-by-the-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO.

ROY LEE HARRIS, ET AL APPELLANTS

Vv. District Court No. 1209 (W)

THE YAZOO CITY MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL,

WITH CONSOLIDATED CASES APPELLEES

MOTION TO DISMISS

MEMORANDUM BRIEF IN RESPONSE TO MOTION FOR

SUMMARY REVERSAL BY THE PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Campbell & Campbell

Williams Building

Yazoo City, Mississippi

John C. Satterfield

Post Office Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEES

Satterfield, Shell, Williams and Buford

Post Office Box 1172

Jackson, Mississippi

OF COUNSEL

Index

Page No.

MOTION TO DISMISS 1-2

MEMORANDUM BRIEF IN RESPONSE TO MOTION FOR

SUMMARY REVERSAL BY THE PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS 1-27

I. THIS IS AN ATTEMPT BY ATTORNEYS FOR NOMINAL

PLAINTIFFS TO OBTAIN AN IRREVOCABLE DECISION

WITHOUT AN OPPORTUNITY FOR THE COURT TO

REVIEW THE RECORD 1

II. THE DISCRETION OF THIS COURT AND THE DISTRICT

COURTS IS NOT DESTROYED BY STATISTICS 7

III. THERE IS NO TRUE BASIS FOR MANY OF THE ALLEGA-

TIONS OF PLAINTIFFS' COUNSEL IN THEIR MOTION

FOR SUMMARY REVERSAL AND NO RECORD PRESENT TO

CORRECT THESE ERRORS 14

IV. REPLY TO THE MEMORANDUM FILED UPON MOTION FOR

SUMMARY REVERSAL BY THE PLAINTIFFS 20

V. DESEGREGATION FOLLOWED BY RESEGREGATION IS NOT

THE OBJECTIVE OF THIS COURT. THE LASTING EFFECT

IS THE ULTIMATE OBJECTIVE SOUGHT HERE 23

Cases Cited

Acree v. County Board of Education of Richmond

County, Georgia, 399 F.24 151

Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County,

Florida wv. Braxton, 402 F.2d 900

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686,

98 L.Ed, 873

Cooper v. Aaron, 338 U.S. 27, 3. L.Ed.24 1,

78 S.Ct. 1397

Dallas County v. Commercial Union Assurance Co.,

286 7.24 388

Freeman v. Gould School District, 405 7.24 1153

Goss v. Board of Education Knoxville, Tenn.

406 P.24 1183

Green v. American Tobacco Co., 391 r.24 97

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, Virginia,

391 U.S. 430, .20 L.,.B4.24 716, 88 S.Ct, 168°

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board,

5th Circuit (May 28, 1969)

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 F.Supp 485

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of Jackson, Tenn.,

391 U.8, 450, 20 1.B4.24 733, 88 S.Ct. 1700

Raney v. Board of Education of Gould School District,

391 U.S. 443, 20 L.Pd.24 727, 88 S.Ct. 1697

Standard Oil Company v. Standard Oil Company,

252 7.24 65

Taylor v. Cohen, 445 F.2d 277

United States and Carr v. Montgomery County Board of

Education, 37 Law Week 4461 (June 2, 1969)

U.S.A. v. Cook County, 404 r.24 1125

United States v. 88 Cases, 187 F.2d 967

ii.

Page No.

10

10

23

24

17.

20

23

21

21

24

10

21,

22

23

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO.

ROY LEE HARRIS, ET AL APPELLANTS

V. District Court No. 1209 (W)

THE YAZOO CITY MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL,

WITH CONSOLIDATED CASES APPELLEES

MOTION TO DISMISS

Now come the above named appellees, for the reasons hereinafter

stated, and respectfully move the Court to dismiss the Motion for

Summary Reversal in the above said action:

I.

This Court will not act upon a Motion for Summary Reversal

which motion would rule upon the rights of litigants not now before

the Court but who have filed notice of appeals and will be brought

later before the Court in these consolidated cases through the

orderly process of appeal.

1x.

The exhibits "A" through "L" to Motion for Summary Reversal

were not provided to counsel for appellees as a part of the said

Motion served on counsel, in violation of Rule 25 of the Federal

Rules of Appellate Procedure.

Til.

This Court will not act upon an appeal and Motion for Summary

Reversal of the decision of the District Court without having before

it the record as designated by the parties to the suit. No such

record is before the Court on this Motion.

1Vv,

There has been filed in the suit of United States of America

v. Hinds County School Board, et als, Civil Action No. 4075, Jackson

Division, an appeal by the plaintiffs. Notice of appeal was duly

served upon the attorneys of record in said proceeding on Friday,

June 13. By stipulation the evidence in said proceeding was made

a part of the record in the above styled cause. The Court will not

act upon a Motion for Summary Reversal of the above styled cause

without having before it the record in said Cause No. 4075, United

States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi,

Jackson Division, which, by stipulation, was made a part of the

record herein.

VV.

Those grounds for dismissal set out in Response to Motion for

Summary Reversal attached hereto and made a part hereof.

Respectfully submitted,

DIC te,

mas H Campbell, Jr

Campbell & Campbell

Williams Building

Yazoo City, Missigsippl

A n C. Satterfiel

Jats a and Buford

V Post Office Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi

AFFIDAVIT BY COUNSEL OF RECORD

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

COUNTY OF YAZOO

Personally appeared before me, the undersigned authority

in and for said County and State, T. H. Campbell, Jr. and John

C. Satterfield who first being duly sworn state on oath that

they are attorneys of record for the Yazoo City Municipal Se-

parate School District, et al, parties to Civil Action No. 1209

(W) pending in the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Mississippi and now pending on appeal in the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

Affiants further state on oath that when they received the

said Motion for Summary Reversal and the Memorandum in support

thereof, they did not receive copies of any of the exhibits al-

leged to be attached thereto, including but not limited to Ex-

hibit "J" which is alleged to be "a compilation of the statis-

tical data for each school district". The extent to which such

compilation may or may not be correct is unknown to these affiants.

SWORN TO and subscribed before me this the 18% day of June,

a [Lf 7 Sl as

NOTARY PUBLIC

MY COMMISSION EXPIRES:

1969.

My Commission Expires Des. 16, 1972

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO.

ROY LEE HARRIS, ET AL APPELLANTS

Vv.

THE YAZOO CITY MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL,

WITH CONSOLIDATED CASES APPELLEES

MEMORANDUM BRIEF IN RESPONSE TO MOTION FOR

SUMMARY REVERSAL BY THE PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

I.

THIS IS AN ATTEMPT BY ATTORNEYS FOR NOMINAL

PLAINTIFFS TO OBTAIN AN IRREVOCABLE DECISION

WITHOUT AN OPPORTUNITY FOR THE COURT TO

REVIEW THE RECORD.

Throughout the years we have noted the "psychological approach”

of the attorneys for plaintiffs in cases of this nature. As an

illustration, the case here (together with twenty-four other cases)

was heard by Judges William Harold Cox, Dan M. Russell and Walter

Nixon, all of the Southern District of Mississippi. Yet the motion

refers on pages 1, 6 and 13 to "Judge Harold Cox". This is patently

an attempt to mislead the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit and

to establish (without any foundation whatsoever) that one of the

judges of the United States District Court for the Southern District

of Mississippi has taken Scion contrary to the direction or admoni-

tion of the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit.

The attorneys for the plaintiffs have very cleverly and astutely

brought about what they now regard as an impasse. They have obtained

the Jefferson decree which prevents any school official from attempt-

ing to influence any child or parent so that any child would be sent

to a school predominantly of the opposite race. Having obtained

this provision of the Jefferson decree and holding this sword over

the heads of all school officials, the same persons now say that

because sufficient desegregation has not been obtained, "freedom of

choice must be abandoned”.

We challenge the good faith of the plaintiffs and particularly

of the attorneys for the NAACP National Defense Fund when they (a)

obtained such a provision preventing the officials' being able to

bring about a reasonable mixing of the races and (b) thereupon take

the position that "freedom of choice" should be abandoned because it

has not brought about such mixing. The District judges in this and

consolidated cases found as follows:

Every school official who testified in every one of these cases

before the Court testified convincingly before this Court that

this provision of this model decree had interfered with a fair

and just and proper operation of the freedom of choice plan in

these schools. Yet, like Prometheus (chained to a rock) these

schools are ordered by the Court to shoulder this very posi-

tive and important duty of desegregating these schools while

the Court denies them the right to counsel with and persuade

parents to let their children enter a school predominantly of

the opposite race. This Circuit has steadfastly refused to

modify that provision in the model decree in any manner, or

to any extent and considers such provision as an important

matter of policy to be changed only by the United States

Court of Appeals for this Circuit sitting en banc.

This motion is an attempt to have the Courts take over the ad-

ministration of thirty-three school districts, without an opportunity

to review the differing facts affecting each district.

The Court of Appeals of the Eighth Circuit stated on January 15,

1969, in Freeman v. Gould Special School District of Lincoln County,

Arkansas, 405 F.2d 1153, that:

We do not think it within the province of the federal court

to pass upon and decide the merits of all of the internal

operative decisions of a school district. However, even if

we were to pass upon the merits of this issue, we do not

think that we could say that the Board was capricious or

arbitrary in its attempt to resolve this internal dispute

between the teachers and the principal of the school. There

must be some degree of harmonious cooperation in school ad-

ministration to insure an efficient use of public funds and

a reasonably satisfactory school program. School boards are

representatives of the people, and should have wide latitude

and discretion in the operation of the school district, in-

cluding employment and rehiring practices. Local autonomy

must be maintained to allow continued democratic control of

education as a primary state function, subject only to clearly

enunciated legal and constitutional restrictions.

Of course, it‘is recognized that the employment or reemployment

of teachers should be carried on by the school districts without re-

gard to impermissible racial factors resulting in discrimination

under the Constitution of the United States. This is recognized in

Freeman as follows:

While the school boards in Arkansas have the right to decide

whom they are going to employ or re-employ, the basis for fail-

ing to re-employ must not be on impermissible constitutional

grounds. Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School Dis-

trict No. 32, 365 F.2d 770 (8 Cir. 1966) (racial discrimination);

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4 Cir. 1966), cert denied 385

U.S. 1003, 87 S.Ct. 706, 17 L.B4.24 542 (racial discrimination);

Shelton v. Tucker, supra, (a disclosure statute violative of

the right of associational freedom, closely allied to freedom

of speech).

In Freeman the Court of Appeals affirmed the finding of the Dis-

trict Court that the complainants, six Negro school teachers whose

annual teaching contracts were not renewed, were not entitled to

judicial relief because the failure to renew arose from a dispute

with the principal of the school, without regard to impermissible

constitutional requirements. This is a signal recognition of the

fact that schools should be maintained and operated by educators

rather than by judges.

The judges of the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit have

recognized the fact that educational problems are not the subject

of judicial review except to the extent that the same may violate

a basic concept of constitutional rights. This is well stated in

the concurring opinion of Circuit Judge Coleman in Board of Public

ye

Instruction of Duval County, Florida v. Braxton, 402 F.2d 900,

August 29, 1968. This case was decided by a panel composed of

Circuit Judges Wisdom and Coleman and District Judge Rubin. It in-

volved actions taken by the above Board of Public Instruction, par-

ticularly the "minority transfer policy" which had been adopted by

such Board. It was a case in which .0045 per cent of the Negro

students attended predominantly white schools and no whites attended

predominantly Negro schools. The Board had "combined a geographical

attendance zone system with freedom of choice.... In particular,

the Board's policy of permitting minority to majority transfers

pointed toward resegregation." The District judge ordered a modifi-

cation of the transfer policy to the extent that it would be limited

to those students who might transfer from a school where students of

his race are a majority to any school within the system where students

of his race are a minority. The Fifth Circuit affirmed. In his con-

curring opinion Circuit Judge Coleman referred to Green and said:

Significantly, the Supreme Court further said: "Moreover,

whatever plan is adopted will require evaluation in practice,

and the Court should retain jurisdiction until it is clear

that state-imposed segregation has been completely removed."

The Court then concluded, "If there are reasonably available

other ways, such for illustration as zoning, promising

speedier and more effective conversion to a unitary, non-

racial school system, 'freedom of choice' must be held un-

acceptable”.

The problem inherent in a zoning plan is that people are free

to move about as they see fit. Therefore, if they dislike the

zone in which they are placed they will move to another. This

often results in far more glaring segregation than that which

existed prior to the inauguration of the plan. The end result

of the zoning approach, if extensively exercised, is that large

sections of the country may become a collection of zones or

pockets, where only one race would be dominant. The National

experience with the so-called ghettos in the large cities would

indicate the undesirability of such an outcome....

Circuit Judge Coleman is not only a lawyer but he is also an

historian. The following statement in his concurring opinion will

(if not now, at least within the next twenty years) be recognized as

the most searching and penetrating statement in the field of school

administration which has been made since Brown I:

Just as surely as this country could not remain half slave

and half free we cannot long maintain an effective school

system half managed by the States and half controlled by

Federal officials, with the Courts trying to supervise them

both.

The statement of Circuit Judge Coleman is borne out by the find-

ing of Circuit Judge Duffy of the United States Court of Appeals of

the Seventh Circuit in U.S.A. v. Cook County, 404 F.24 1125, 1136,

in his dissenting opinion. The facts stated by him were not contrary

to the majority opinion. The application of numerous constitutional

principles to such facts resulted in his dissent. Circuit Judge

Duffy said:

In 1948, the Coolidge School had an enrollment of 70% white.

In 1956, Coolidge had become a predominantly Negro school

with a student enrollment of 99% Negro. There is absolutely

no evidence in this record that during this eight-year period,

the School Board did anything to change the racial composition

in the Coolidge School. The attendance boundaries for Coolidge

in 1956 were identical with those which existed in 1948. It

seems obvious that the failure to change boundaries in 1964

could not and did not play any part in the Coolidge School

becoming a 99% Negro school during the period from 1948 to

1956.

However, the majority opinion of the Court of Appeals of the

Seventh Circuit recognized in Cook County the right and duty of the

District Courts to determine the facts as presented to them by the

parties litigant. It affirmed the action of the District Court below,

saying:

In the Brown, II case, Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S.

294, at 300-301, 75 S.Ct. 753, at 756, 99 L.Ed. 1083 (1955),

the Court said, that with respect to desegregating a school

system, lower courts "may consider problems related to adminis-

tration, arising from the physical condition of the school

plant, the school transportation system, personnel, revision

of school districts and attendance areas into compact units

to achieve a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and

regulations which may be necessary in solving the foregoing

problems."

There is no hard and fast rule that tells at what point de-

segregation of a segregated district or school occurs. The

court in Northcross said the "minimal requirements for non-

racial schools are geographic zoning, according to the capacity

and facilities of the buildings and admission to a school ac-

cording to residence as a matter of right." 333 F.2d at 662.

On the other hand, "The law does not require a maximum of

racial mixing or striking a rational balance accurately re-

flecting the racial composition of the community or the school

population.” United States v. Jefferson County Board, 372 F.2d

836, 847, n. 5 (5th Cir. 1966) aff'd en banc, 380 F.24 385

(5th Cir.), cert. denied, Cado Parish School Board v. United

States, 389 U.S. 840, 88 S.Ct. 67, 19 L.Bd4.24 103 (1967). The

district court's judgment here must be made upon a determina-

tion whether defendants -- by what they have done since the

beginning of the 1968-69 school year, under the July 8 and

July 22, 1968, orders -- have shown a good faith performance,

and whether the plans they may submit hold promise of future

good faith performance toward achieving a non-racially struc-

tured school system which is reasonably related to the objec-

tive of the court's order.

It is true, of course, that this Court admonished the three

District judges here to commence a hearing in each case at the earli-

est practicable time, no later than November 4, 1968. The three

District judges not only followed this admonition but they commenced

this consolidated hearing on October 7, 1968. Because of the many

suits involved and the many litigants affected, the hearing extended

for a long period of time. Under our system of justice, every person

is entitled to be heard by the courts of our land. There can be no

criticism of the judges of the District Courts here because they per-

mitted the litigants to present testimony, then considered such tes-

timony, and thereafter rendered their considered opinion thereon.

It is a physical, mental and constitutional impossibility for

courts of original jurisdiction to receive, consider and review

evidence, permit the parties to present briefs on opposing sides,

review such briefs and enter a decision in a limited period of

minutes, hours or days. We respectfully submit that the judges of

the District Courts here involved conformed, to the best of their

ability and within the limitations of our Constitution, to the de-

sire of this Court and to their desire (as well as the desire of

those involved) to reach as soon as is reasonably possible a determi-

nation of the rights of the thousands and hundreds of thousands of

students and parents affected by these cases.

It appears to us to be unseemly for attorneys to insist that

our American form of judicial determination should be destroyed and

that our appellate courts reach decisions and make determinations

without an opportunity of reviewing the evidence introduced in accor-

dance with our judicial procedures. What is asked by the movants is

that there be entered judgments in these cases based, not upon the

facts and the law as presented to the courts of our land, but upon

what the attorneys (as advocates) say was presented.

Il.

THE DISCRETION OF THIS COURT AND THE DISTRICT

COURTS IS NOT DESTROYED BY STATISTICS

Although the schools of Yazoo City, Mississippi, are located

within the area served by the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit,

the questions here affect all school children in the United States.

Hence it is of great value to consider the decisions not only of the

Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit but of the other Courts of Ap-

peal, and, of course, of the Supreme Court of the United States.

A study of the Motion for Summary Reversal reveals it is not

only contrary to procedures followed consistently by the Court of

Appeals of the Fifth Circuit, but is diametrically opposed to actions

taken by other Courts of Appeal throughout the United States.

“Fw

An illustration is the decision of the United States Court of Appeals

of the Sixth Circuit in Goss et al v. Board of Education, City of

Knoxville, Tenn. (February 10, 1969), 406 F.2d 1183, in which that

Court held:

Preliminarily answering question I, it will be sufficient to

say that the fact that there are in Knoxville some schools

which are attended exclusively or predominantly by Negroes

does not by itself establish that the defendant Board of

Education is violating the constitutional rights of the

school children of Knoxville. Deal v. Cincinnati Board of

Bducation, 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert. denied, 389

U.S. 847, 88 S.Ct. 39, 19 L.E4d.24 114 (1967); Mapp v. Bd.

Of Education, 373 P.24 75, 78 (6th Cir. 1967). Neither

does the fact that the faculties of some of the schools are

exclusively Negro prove, by itself, violation of Brown.

The movants would condemn any system, regardless of the true

freedom of choice existing therein, unless it reaches a certain statis-

tical level. The Courts of Appeal throughout the United States have

declined to follow this position. In Goss, the Court of Appeals of

the Sixth Circuit said:

On the general subject of the progress of desegregation in the

Knoxville schools, it is important to note that the Superinten-

dent of Schools testified that any Negro can transfer out of a

school in which his race is in the majority to a school at-

tended by a majority of whites. This is in contrast to the

freedom of choice or transfer plan condemned by the Supreme

Court in Monroe v. Bd. of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450, 88 S.Ct.

1700, 20 L.Ed.2d 733 (1968) and Green v. County School Bd.,

391 U.S. 430, 88 S.Ct. 1689, 20 1L..Ed.24 716 (1968).

The basic problem confronting the trustees of the school dis-

tricts throughout the United States (and especially the South) is

well stated by the Court of Appeals of the Sixth Circuit in Goss as

follows:

We do not believe it is for us or the District Judge to com-

mand a school district to adopt any particular plan for com-

plying with relevant law so long as its school authorities

are, in good faith, employing and implementing plans that

are consistent with fulfilling their total duty to all the

student body and at the same time making meaningful progress

in the area of desegregation. In Green v. County School Bd.,

391 U.S. at 439, 88 S.Ct. at 1695, the Supreme Court said:

"There is no universal answer to complex problems of

desegregation; there is obviously no one plan that will

do the job in every case. The matter must be assessed

in light of the circumstances present and the options

available in each instance. It is incumbent upon the

school board to establish that its proposed plan prom-

ises meaningful and immediate progress toward dis-

establishing state-imposed segregation.”

Unless Mr. Justice Brennan's language in Green, supra, that:

"School boards such as the respondent then operating

state-compelled dual systems were nevertheless clearly

charged with the affirmative duty to take whatever

steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary system

in which racial discrimination would be eliminated root

and branch.” 391 U.S. at 437-438, 88 S.Ct. at 1694.

means that somehow the Knoxville school authorities must pro-

portionately spread its 15% Negro pupils among the 85% white

school population, we consider that Knoxville is currently

obeying the law.

After discussing the percentages involved (which are very close

to those now before the Court in a number of these cases and particu-

larly the case in which this brief is filed), the Sixth Circuit ex-

pressed its bewilderment with the phraseology utilized by Civil

Rights activists and sometimes repeated by the courts, as follows:

We are not sure that we clearly understand the precise intend-

ment of the phrase "a unitary system in which racial discrimi-

nation would be eliminated," but express our belief that

Knoxville has a unitary system designed to eliminate racial

discrimination. In Monroe v. Bd. of Commissioners, 380 F.2d

955, 958 (6th Cir. 1967), we expressed our view that the end

product of obedience to Brown I and II need not be different

in the southern states, where there had been de jure segrega-

tion, from that in northern states in which de facto discrimi-

nation was a fortuity. Our observations in that regard were

not found invalid by the Supreme Court's opinion reversing our

Monroe decision. See Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391

U.S. 450, 88 S.Ct. 1700, 20 L.BE4.22733 (1968).

It develops that "what is sauce for the goose, is sauce for the

gander". The parents of children attending the public schools of

the United States have different ideas and different wishes. They

desire to exercise their freedom in different ways under our

Constitution. An illustration is the decision of the Court of Ap-

peals of the Fourth Circuit in Taylor v. Cohen, 445 F.2d 277, which

was decided on December 5, 1968. In this decision the Court stated

the applicable rule as follows:

HEW urges as an alternative defense the plaintiffs' lack of

standing. Standing is one of "the most amorphour /concepts/

in the entire domain of public laws". It is not an absolute.

It is a variable, closely related to the nature of the con-

troversy and the relief sought. Parents of children attending

public schools are vitally interested in every phase of the

school system, including its finances and plan of assignment.

Nevertheless, they do not have standing to seek judicial inter-

ference with a school board's exercise of its discretionary

power. On the other hand, parents do have standing to enjoin

a board's unconstitutional action, whether it originates in

the school board itself or is the product of pressure brought

against the board by a government agency. Griffin v. School

8d. of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218, 84 S.Ct. 1226, 12

L.Ed.2d 256 (1964).

In their brief, the movants necessarily refer repeatedly to

Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181, which included these cases with a

total of forty-four cases from Louisiana, Mississippi, and Georgia.

This involved motions to the same effect as the motion now pending

before this Court. Such motions were denied. In denying these

motions, this Court referred to Acree v. County Board of Education

of Richmond County, Georgia, 399 F.2d 151 (1968 - Fifth Circ.), in

which this Court stated the applicable rule to be as follows:

This court is not adequately equipped for the trial, decision

and hearing of original suits for injunction, it being drdi-

narily a court without original jurisdiction. In extreme

cases we have found it necessary to issue original injunction

orders. See Meredith v. Fair, 5 Cir., 306 ».24 374, and

United States v. Lynd, 5 Cir., 301 F.2d 818. The court does

not find this to be an appropriate case for the issuance of

an original injunction because of the state of the record

now before us, and especially in view of the requirements

recently enunciated by the Supreme Court in Green et al. v.

County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia, et al, 391

U.S. 430, 88 S.Ct. 1689, 20 L.Ed.24 716 decided May 17, 1968,

Monroe et al. v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Jack-

son, Tenn., et al., 391 U.S. 450, 88 S.Ct. 1700, 20 L.F4.24

733, decided May 27, 1968, and Raney et al. v. Board of Edu-

cation of The Gould School District, et al., 391 U.S. 443,

88 S.Ct. 1697, 20 L.Ed.2d 727 decided May 27, 1968.

-l0=

In fact, the motion calls upon this Court to take action without

having an opportunity to consider the testimony presented to the Dis-

trict Court and without any record whatsoever before this Court which

could be the basis of an impartial decision.

Long ago it was said that "Haste makes waste". The defendants

do not intend to attempt in any manner to delay the hearing of this

cause. They did not ask that the hearing be continued beyond the

date set by the judges of the District Court, they do not ask for

any delay in the regular, proper course of judicial proceedings.

They simply and only ask that this Court act when it has before it

all of the facts which were presented to the United States District

judges when the case was decided. This is a right which has been

vested in every individual who is a citizen of the United States

from the adoption of the Constitution to this date. It would be

abrogated and destroyed if the present motion should be sustained.

Tt would mean that our courts would act upon statements contained in

briefs by attorneys without the opportunity of reviewing the record

prepared and presented by litigants in accordance with the procedures

set up in our judicial system, considered by courts of original

jurisdiction, and then presented, upon proper appeal, to our appellate

court.

After a full and detailed hearing in all of these twenty-five

cases (involving thirty-three school districts) the three District

judges, who were acting in good faith and must be presumed by this

Court to have so acted, found as follows:

But a very careful examination of the witnesses and analysis

of their testimony in these cases revealed to the Court not

one instance where any colored parent, or colored child did

not do exactly what they wanted to do in deciding as to the

school which the colored child would attend. There are many

Tn

reasons (and very important reasons) why colored children

have not sought to attend formerly all-white schools. The

primary reason is that the vast majority of all schools at-

tended by colored children qualify for the government sub-

sidiary as "target schools.” They are provided by the govern-

ment with free lunches, and even improved facilities and work-

ing tools in their shops, because the majority of the parents

in such schools are in low income brackets. A disruption of

these benefits would be disastrous to those children who would

be obliged to leave school and lose all educational advantages

now available to them there. It is such facts and circum-

stances which have caused the courts to wisely observe, time

and again, that there is no easy and quick and ready-made

cure for the past ills of state enforced segregation. The

problem and its cure must yield to the facts and circumstances

in each particular school case. The cure must not result in

a destruction of the wholesome objective of the plan. It is

a sorry and very strange principle of constitutional law which

would foster by its application a catastrophic destruction of

the right sought to be protected and enjoyed.

There is nothing whatsoever set forth in the Motion for Summary

Reversal which demonstrates that the finding of the three District

judges here is without foundation in fact and is not supported by

the evidence.

One of the most important findings by these judges, based upen

the evidence before them, is as follows:

Well trained colored teachers in active service in formerly

colored schools and in formerly white schools in this district

have appeared before this Court and convincingly testified under

oath as a matter of fact that freedom of choice was actually

working in their schools; that perfect harmony and understand-

ing existed in the school and that no danger to the school

system lurked in the implementation of the freedom of choice

plan, but that any kind of forced mixing of the races against

the wishes of the involved parents and children (colored and

white) would result in an absolute and complete destruction of

the school and its system. That is likewise a fair analysis and

characterization of the uncontradicted testimony of experienced

expert witnesses who have spent their lives in school service

in many other states. This testimony does not show that de-

segregation is unpopular with some parents and some children,

but does positively show that any rushed and random forced mix-

ing applied for the sake of immediate mathematical statistics

would literally destroy the school system for both races. In

many instances where the ratio of colored people to white

people is very high, the result would be not to create just

schools, but to create predominantly colored schools, readily

identifiable as such in every instance. The same corresponding

result would follow in areas where the white population is very

dense and few Negroes live.

-l

As to the Yazoo City Municipal Separate School District, there

is no showing whatsoever in the record (which is not now before the

Court) that any parent or child has complained that his or her con-

stitutional rights have been violated in this proceeding. Those

complaining before this Court are brought forward by the zealots

and by eager agents who are representing organizations based outside

of Yazoo City, Yazoo County, and the State of Mississippi. This is

not an instance where individual rights have been affected. It is

an instance in which representatives of organizations are acting be-

cause they are paid to make such complaint, not by parents, not by

students, but by funds the source of which is unknown and, perhaps,

unknowable.

The time has come in these United States that we should cease

to do what was said about the ancient ostrich, which is to "stick

our heads in the sand", or as is said, more colloquially, to "beat

about the bush". These actions are generally and largely solicited

by paid attorneys for propagandist organizations. They do not repre-

sent the true wishes of either the parents or the children whose

names are utilized because under pressure names were signed to a

mimeographed or printed form authorizing attorneys (or attorneys

chosen by such attorneys if they should Yenlai or remove from the

jurisdiction) to proceed with the 1ielsation. The Constitution of

the United States was written for the protection of its citizens.

It was not written to be used as a vehicle for bringing about results

desired by those who might be engaged in the business of the promo-

tion of litigation whether they be supported by private individuals

(not involved in the suit), by foundations, or by public subscrip-

tions obtained after headlines and provocative articles in the

public media.

-13=

In fact, the latest expression by the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit on this question appears in Hall, in which the panel

stated as follows:

We do not abdicate our judicial role to statistics.

It is true, as thereafter stated, that the Court will "listen"

to statistics. This is reasonable and proper. Nevertheless, if

this Court or any court of our land should abdicate its judicial

role to statistics, justice would be lost in the United States of

America.

111.

THERE IS NO TRUE BASIS FOR MANY OF THE ALLEGATIONS

OF PLAINTIFFS' COUNSEL IN THEIR MOTION FOR SUMMARY

REVERSAL AND NO RECORD PRESENT TO CORRECT THESE

ERRORS

We believe that this Court could not legally or morally sustain

plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Reversal of the District Court with-

out the evidence contained in the voluminous record made in the

District Court. The attorneys for the plaintiffs in their brief

refer to exhibits, which they have not supplied to any of the defen-

dants (see affidavit Exhibit A hereto), and make generally erroneous

statements attempting to convince this Court of the alleged failure

of defendants' Jefferson plan of freedom of choice.

We do not know, and cannot know until such exhibits to the

motion are made available to us, whether the so-called Exhibit "J"

thereto correctly sets forth this defendants’ statistics or not, or

for what years or periods.

Plaintiffs' statement on page 5 of their brief, paragraph bh),

as to the number of Negro students in white schools is, as we know,

incorrect.

-llw-

As to paragraph c), our district has achieved substantial

faculty integration practically in that degree required under our

Jefferson decree.

The second paragraph a) incorrectly sets forth the evidence

as to this district and many other districts in that our district

made no admission that pairing or zoning was administratively sound

and feasible. Pairing or zoning is possible, of course, but not

administratively sound or feasible; in fact, it would be disastrous

as shown by the record.

The second paragraph b) is incorrect since we introduced posi-

tive evidence of integration of athletic and extra-curricular activi-

ties in this district.

The second paragraph c) thereon would lead the Court to believe

all of the districts had had full-fledged freedom of choice plans

since 1965, thus having in five years under said plan accomplished

little. Actually, most of the districts, in 1965, after the 1964

Civil Rights Act, with the approval of this Court, immediately in

good faith instituted freedom of choice in the first four grades of

school; then in 1966, in the next four grades, and not until 1967

all twelve grades. Certainly this was true in our district, since

we patterned our plan voluntarily after the Court-imposed plan on

the Jackson, Mississippi, Municipal School District and the District

Court made no such finding as to our district in its opinion.

Our evidence shows that our Jefferson decree plan will work and

is working, as required by Green and recently Hall, and not just

that it could work. The integration of our white schools under our

voluntary plan from 1965 to 1967 worked and especially so since

November, 1967, when we adopted the Jefferson decree. In 1967-1968

w1B=

our Negro students in formerly all white schools increased more than

800% over 1966-1967, and in 1968-1969 increased 700% over 1967-1968.

On top of this per our March, 1969, Cholce Period we will have an

increase of approximately 150% in 1969-1970 over the numbers attend-

ing formerly all white schools in 1968-1969.

In fact the racial composition for Yazoo City High School for

1969-1970 year per Choice Period is as follows:

Total number of students attending school: 768

Total number of white students attending: 669

Total number of Negro students attending: 09

Percentage of Negro students to total enrollment: 12.9%

Percentage of Negro students to total enrollment

by grades:

Grade 9 8.7%

Grade 10 16.5%

Grade 11 11.6%

Grade 12 14.3%

OT

H

© N

i

o

p+

)

Thus we join issue with the statements set forth on page 5 of

the Motion for Summary Reversal. These statements are without basis

in fact and do not reflect the evidence in this case. There is no

"double standard” for school desegregation in Mississippi as between

the Northern District of Mississippi and the Southern District of

Mississippi. The judges in both Districts are interested in and

desire to follow the admonitions of the Supreme Court of the United

States in Green and other cases. Each school district is governed

by the particular facts applying thereto.

But the most glaring error in the Motion for Summary Reversal

is in its complete omission to set out or consider the additional

findings of fact by the District Court, including:

l. New and material issues not heretofore considered by this

Court involving the educational merit of the various available plans,

and the necessity for weighing all factors affecting the same.

2. Evidence introduced as to the harmful psychological and

educational effects of compulsory mixing in all ethnic groups.

1G

3. Evidence of reduced effectiveness in teaching widely

disparate achievement groups in one classroom.

4. The effect of temporary integration as opposed to lasting

integration as shown by evidence.

Additional findings of fact were made a part of the District

Court's opinion of May 13, 1969, by motion of the defendants in

Civil Action 4075, styled United States of America v. Hinds County

Board of Education, et al, (consolidated with this litigation).

These findings present issues not considered in Green, Raney, Monroe

and Carry, and deal with the educational merits of the various roads

to the constitutional goal. In pursuit of this goal, most school

boards chose freedom of choice (or free transfer) plans as the appro-

priate vehicle for the journey. Before freedom of choice plans

came under attack in Green it was not necessary that school boards

explain their preference for this plan over other plans seemingly

more direct in arriving at results. Now that such an attack has

been launched, evidence of the educational advantage of such plans

as opposed to the educational harm to all students, black and white,

of other plans involving enforced mixing was introduced and should

be considered by this Court. Such evidence was not presented in

Green (and its companion cases), yet an invitation for such evidence

does appear in that decision.

The additional findings of fact in the Hinds County case (con-

solidated for purposes of this expert testimony with this case) deal

l. "Of course, where other, more promising courses of action

are open to the board, that may indicate a lack of good

faith; and at the least it places a heavy burden upon the

board to explain its preference for an apparently less

effective method." Green v. School Board of Virginia,

(etc.)

-)7

directly with these educational values and the record contains expert

testimony to support these findings of fact.

1. Expert testimony delineated the adverse psychological effect

upon children who are involuntarily forced to associate with unlike

ethnic groups. The evidence demonstrated that such mixing produces

resentment, hostility, impaired motivation to learn, lowered achieve-

ment and ethnic misidentification (particularly in younger children).

2. Voluntary association with unlike ethnic groups was shown

to be beneficial by expert testimony. Such associations could pro-

mote achievement and motivation and reinforce the child's personality

when voluntarily made.

3. The difficulties and disadvantages of attempting to teach

widely disparate achievement levels within the same classroom was

developed by expert testimony. As opposed to compulsory or arbitrary

pupil assignment, free choice plans were shown to permit whole schools

to develop teaching methods and paces compatible with the achieve-

ment levels localized at such school and permit parents and students

to select schools better suited to the student's abilities.

Resegregation due to any precipitous compulsory mixing plan was

shown to be more pronounced than under slower voluntary plans by ex-

pert opinion evidence and by the results of an independent, impartial

survey of white parents conducted in several of the districts. With

the premise that any "workable" plan must have real prospect for

lasting effect, freedom of choice or voluntary plans were shown to

be the only plans having such prospects. The advantages of inte-

grated education would be largely illusory in a school district

heavily raided by white private schools.

We also definitely and specifically deny that the records show

that "not a single school district has achieved more than token

-18~

faculty integration". The only way this Court can determine the

difference between the attorneys for the movants and the attorneys

for the respondents is to have before it the record in this case.

A review of the record will sustain our position and negate the

position now taken by the attorneys for the movants before this

Court.

It is difficult, using "hindsight" (as distinguished from "fore-

sight") to view the problem of schools in the United States of America

and particularly Mississippi. It is true that fourteen or fifteen

years have elapsed since Brown I. It is also true, however, that the

Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit and other courts have recog-

nized the necessity of proceeding with "all deliberate speed”. This

"deliberate speed" is not a figment of the imagination of the school

authorities. It is and was a statement and finding of the Supreme

Court of the United States and of this Court of Appeals.

We do not blame the attorneys for the plaintiffs herein for

again and again referring to the number of years which have passed.

On the other hand, we do ask this Court to consider the extent to

which the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and other courts have followed

the Supreme Court of the United States in determining that "all delib-

erate speed" did not mean a reversal of educational policies within

a few weeks, a few months, or a few years. Originally, the courts

required two grades per year to be desegregated. Later the pace was

quickened. The passage of time has been judicially recognized as

reasonable and necessary.

Again, we point out that the movants rely upon statistics alone.

It would be a sad day in the history of American jurisprudence if

the discretion of the courts and the rights of citizens became sub-

servient to a bare statement of "statistics". This has been the

-10=

plea of the organizations representing the plaintiffs in many of

these cases. This would abrogate the right of the Court to deter-

mine what is within the broad limits of the Constitution of the

United States. In fact, the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit,

acting through Chief Judge Brown, Circuit Judge Godbold, and Dis-

trict Judge Cabot said, in Hall, "We do not abdicate our judicial

role to statistics.” It is a fact, as properly it should be, that

statistics are one of the elements to be considered by a judge exer-

cising his discretion under the Constitution of the United States

and for the benefit of its citizens. However, if this Court or any

other court were to abdicate the judicial role to statistics, our

system of justice in the United States would be destroyed.

Hence we respectfully submit that statistics alone are not

enough. We also respectfully submit that the changes required by

the recent decisions of the Fifth Circuit (overruling many former

decisions thereof) and the decision of the Supreme Court of the

United States in Brown (overruling many former decisions thereof)

permit public officials to experiment with that which will best

carry out the constitutional requirements. We also respectfully

submit that if such experimentation does not meet with the results

desired by parties (as distinguished from educators) within a few

days, months or years, this should not be abandoned unless it is

shown there is no reasonable probability that the desired result will

be obtained.

IV.

REPLY TO THE MEMORANDUM FILED UPON "MOTION

FOR SUMMARY REVERSAL" BY THE PLAINTIFFS

Complaint is made that there were consolidated twenty-five cases

(affecting thirty-three school districts). We are somewhat at a

2)

loss to understand why the movants complain of this action. Certain-

ly, it expedites the determination of twenty-five cases for them to

be consolidated, and for the evidence therein to be heard consecu-

tively. The fact is that the attorneys for these plaintiffs do not

desire justice. They desire what they desire, regardless of the Con-

stitution, regardless of due process of law, regardless of a reason-

able and proper presentation to the Courts.

Within the last few weeks there have been a plethora of decisions

by different panels of the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit.

Also there has been a decision of the Supreme Court of the United

States supplementing Green, Raney and Monroe. This is the case of

United States and Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education, re-

ported in 37 Law Week 4461, which was rendered on June 2, 1969. The

opinion was written by Mr. Justice Black and there was no dissent

thereto. The subject matter of this opinion is best stated by quot-

ing the first paragraph of the opinion therein rendered as follows:

In this case the United States District Court at Montgomery,

Alabama, ordered the local Montgomery County Board of Educa-

tion to bring about a racial desegregation of the faculty and

the staff of the local county school system. 289 F.Supp. 647

(1968). Dissatisfied with the District Court's order, the

board appealed. A panel of the Court of Appeals affirmed the

District Court's order but, by a two to one vote, modified

it in part, 400 P.24 1 (1968). A petition for rehearing en

banc was denied by an evenly divided Court, six to six,

thereby leaving standing the modifications in the District

Court's order made by the panel. On petitions of the United

States as intervenor in No. 798, and the individual plaintiffs

in No. 997, we granted certiorari. 393 U.S. 1116 (1969).

Tt will be noted that the opinion of the panel was by a vote of

two to one, and that a petition for rehearing en banc was denied by

an evenly divided Court, six to six.

This case chiefly involved the matter of teacher desegregation

but it also set forth basic principles supplementary to those an-

nounced in Green, which are of importance here.

=21~

The necessity of permitting boards of education throughout the

United States to utilize "experimentation" in obtaining proper educa-

tional facilities for all students, regardless of race, was recognized

as follows:

In so holding, the Court of Appeals made many arguments against

rigid or inflexible orders in this kind of case. These argu-

ments might possibly be more troublesome if we read the Dis-

trict Court's order as being absolutely rigid and inflexible,

as did the Court of Appeals. But after a careful consideration

of the whole record we cannot believe that Judge Johnson had

any such intention. During the four or five years that he

held hearings and considered the problem before him, new

orders, as previously shown, were issued annually and some

times more often. On at least one occasion Judge Johnson, on

his own motion, amended his outstanding order because a less

stringent order for another district had been approved by the

Court of Appeals. This was done in order not to inflict any

possible injustice on the Montgomery school system. Indeed

the record is filled with statements by Judge Johnson showing

his full understanding of the fact that, as this Court also

has recognized, in this field the way must always be left

open for experimentation.

Also, the position of the movants here is negated by the state-

ment of the Supreme Court of the United States in Carr which quotes

the position of the Department of Justice as follows:

As the United States, petitioner in No. 798, recognizes in its

brief, the District Court's order "is designed as a remedy for

past racial assignment.... We do not, in other words, argue

here that racially balanced faculties are constitutionally or

legally required." Brief for the United States, at 13.

It seems that the movants are not interested in public education.

The effect upon the educational system is immaterial to them. The

Supreme Court of the United States disagrees with this position and

specifically so did in Carr as follows:

Despite the fact that the individual plaintiffs in this case

have with some reason argued that Judge Johnson should have

gone farther to protect their rights than he did, we approve

his order as he wrote it. This, we believe, is the best

course we can take in the interest of the plaintiffs and the

public school system of Alabama.

‘Hence, this Court will consider not only the desires of the at-

torneys for the plaintiffs, but it will give equal weight to the best

interest of the public school system of Mississippi.

Wy 4 1

Vv.

DESEGREGATION FOLLOWED BY RESEGREGATION IS NOT

THE OBJECTIVE OF THIS COURT. THE LASTING EFFECT

IS THE ULTIMATE OBJECTIVE SOUGHT HERE.

The courts have always recognized that constitutional rights

will not be sacrificed to violence, disorder or disagreements of

any person, see particularly Cooper, Buchanan. The courts do not

act upon apprehensions and possibilities. In Monroe the Supreme

Court stated, "We are frankly told in the (school board's) brief

that without the transfer option it is apprehended that white students

will flee the school system altogether". The apprehension thus ex-

pressed was necessarily disregarded by the court.

Also in Lee, rendered by the three judge court on August 28,

1968, it was reiterated that public officials cannot yield their

constitutional duties "because of the possibility that white students

will flee the public school system or that the public will discon-

tinue its financial support of its public school systems”.

Nevertheless the courts may consider the best evidence of what

may be reasonably expected to occur in the future. Judges are

neither seers nor soothsayers. Yet in Green the duty was placed

upon the District Courts to weigh the plan administered or proposed

"in the light of the facts at hand and in the light of any alterna-

tives which may be shown to be as feasible and more promising in

their effectiveness”. In that case further reference was made to

the possibility of "more promising courses of action” which may be

shown to be open to the board.

The Supreme Court of the United States recognizes that the

"inevitable consequence” which will follow action by school officials

is the primary and basic consideration. Neither the Courts nor the

hd A

trustees of the school districts are concerned with the temporary

situation. This is illustrated by the statement in Monroe as follows:

While we ... indicated that "free transfer" plans under some

circumstances might be valid, we explicitly stated that "no

official transfer plan or provision of which racial sedgrega-

tion is the inevitable consequence may stand under the

Fourteenth Amendment.” Id., at 689, 10 L.Ed.24 at 636.

It is very difficult to establish the reasonably anticipated

results of future actions. Such results can best be ascertained by

a completely objective independent and scientifically designed opinion

poll or survey which determines the reasonably anticipated action of

the parents of such students if integration is required by judicial

action.

When this record is before the Court in the orderly course of

appeal, it will contain a scientific, objective and disinterested

survey made by qualified experts to determine the actual result which

may be reasonably expected if pairing or zoning were to be required

in the Yazoo City Municipal Separate School District. This survey

was made by Dr. Harold Knight and Dr. John D. Alcorn, members of

the faculty of the University of Southern Mississippi and shown to

be fully qualified in this field. It complied with all the require-

ments of applicable cases, including Standard Oil Company v. Standard

Oil Company, 252 F.2d 65 (CA 10th, 1958); United States v. 88 Cases,

More or Less, etc., 187 F.2d 967 (CA 3rd, 1951); as well as Green Vv.

American Tobacco Company, 391 F.2d 97 (CA 5th, 1968) and Dallas

County v. Commercial Union Assurance Company, 286 F.2d 388 (CA 5th,

1961).

This is the best evidence available and was admitted both under

the authority of the above cases and under the "best evidence rule”.

It revealed that if there were a pairing of schools or the use of

Dl

geographic zoning on a basis which would approximate a racial balance

of the students now enrolled in each of the schools (the evidence

showed that the pattern of residence would very nearly bring about

this result), the actual withdrawal of white students would result

in student bodies composed of 93 per cent students of the Negro race

and 7 per cent students of the white race.

This will, of course, be fully developed when the matter is con-

sidered by this Court in the due and orderly course of appeal.

We are intrigued by the use of catch phrases which have, un-

fortunately, been effective in the past. One illustration is the

use of the term on page 3 of the Memorandum Brief of the phrase,

"a moratorium upon constitutional rights". Another, on the same

page, is a "double standard" for school desegregation. Another is

the reference on page 13 to "defendant's smoke screen", and still

another, the statement on the same page that the order of the Dis-

trict Court "challenges the very foundations of our judicial system”.

As a matter of fact, it would waste the time of this Court to

quote the many statements by the Supreme Court of the United States

that each school district has problems of its own and must be treated

by the District Court as an entity. There is no such thing as a

"double standard" involved in this or other cases. The fact that a

different situation may exist in one school district as compared to

another is a far cry from a "double standard". The reference to

certain decisions by Judge Orma Smith of the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Mississippi has no bearing upon

the cases now before the Court because of the material differences

in the facts which are shown in such cases.

We do not quarrel with the position that the District Courts

as well as the trustees of the school districts should and must use

28.

all speed that is consistent with providing reasonable and proper

education for the students. We do not agree that, because a certain

degree of mixing desired by parties is not reached within a limited

period of time, this constitutes a "moratorium upon constitutional

rights". Our position definitely is that the judges here, upon con-

flicting evidence, have found that reasonable and proper steps have

been taken in this School District and that constitutional rights

are being preserved thereby. The District judges have expressly

found that the Board of Trustees of this District are acting in good

faith. There is no evidence to the contrary. No attempt has been

made in the Motion for Summary Reversal and the Memorandum attached

thereto to point out any fact which would justify this Court in up-

setting the finding of the District judges in this case.

In closing we call attention to Hall, et al v. St. Helena Parish

School Board, et al, rendered by a panel of this Court on May 28, 1969,

consisting of Chief Judge Brown, Circuit Judge Godbold, and District

Judge Cabot, ‘There the Court considered cases which were before it

at a previous time when the record was not available to the Court,

and a motion similar to that here involved had been made by the appel-

lants. This motion was overruled and the case came on for hearing

in due course of judicial procedure. This involved twenty-nine

school districts within the Western District of the United States

Court for Louisiana and eight parishes within the District Court for

the Eastern District of Louisiana. It also involved the Tangipahoa

Parish School Board, which was an appellant from another decree in

the Eastern District. The panel in Hall declined to grant the re-

lief now asked in the consolidated cases here, as follows:

We are urged by appellants to order on a plenary basis for

all these school districts that the district court must reject

26

freedom of choice as an acceptable ingredient of any desegre-

gation plan. Unquestionably as now constituted, administered

and operating in these districts freedom of choice is not ef-

fectual. The Supreme Court in Green recognized the general

ineffectiveness of freedom of choice. But in that case, con-

cerning only a single district having only two schools, the

court declined to hold "that 'freedom of choice' can have no

place in ... a plan" that provides effective relief, and

recognized that there may be instances in which freedom of

choice may serve as an effective device, and remanded to

the district court with directions to require the board to

formulate a new plan.

We respectfully submit that

should be denied and that, if so

should be required to follow due

to this Court the appeal and the

pass with all facts before it.

the Motion for Summary Reversal

desired by them, the appellants

and proper procedure in presenting

record upon which this Court could

Respectfully submitted,

OQ) Gun, vi

Thomas H. Campbell, Jr.

Campbell & Campbell

Williams Building

Yazoo City, Mississippi

//John C.

Satterfield,

Post Office Bo

Yazoo City,

Satterfiel —

Sheld,

166

Mississippi

Williams and Buford

27

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing Memorandum Brief

in Response to Motion for Summary Reversal by the Plaintiffs-

Appellants were served on appellants on this 19th day of June, 1969,

by mailing copies of same, postage prepaid, to their counsel of

record at the last known address as follows:

Melvyn R. Leventhal

Reuben V. Anderson

Fred L. Banks, Jr.

538-1/2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Jack Greenberg

Jonathan Shapiro

Norman Chachkin

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York