Memorandum Opinion

Public Court Documents

November 3, 1986

7 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Memorandum Opinion, 1986. 8fd856d3-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9a30b569-2e3f-4962-a54b-0f772ebf3ee4/memorandum-opinion. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

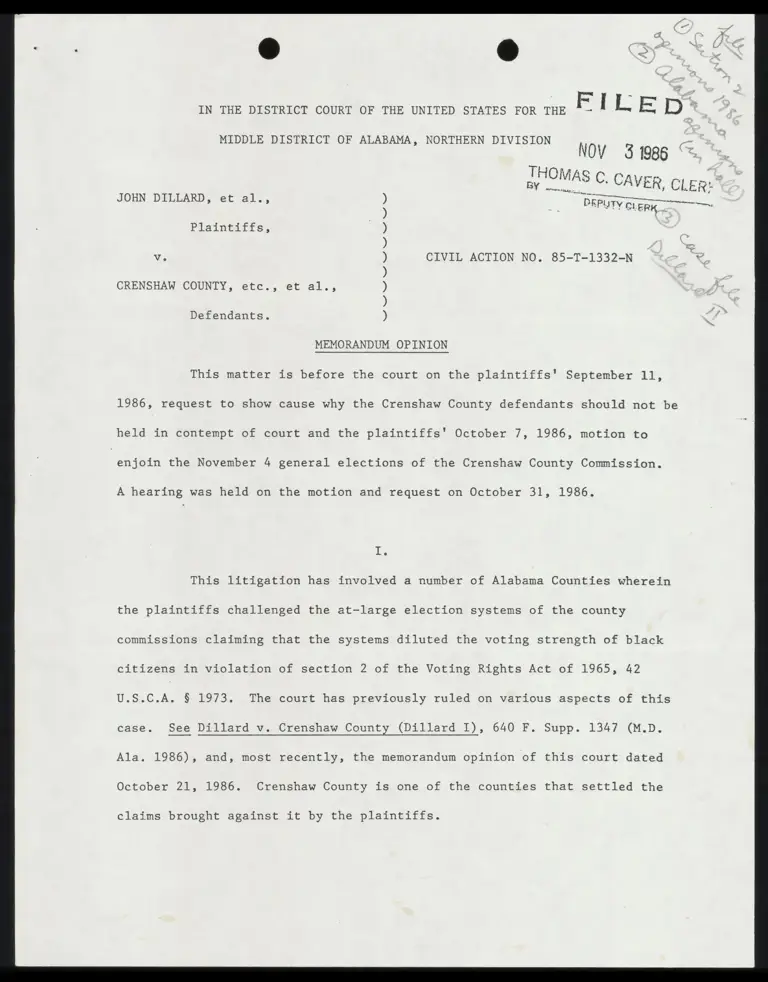

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE F I L E D

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION

NOV 31886 =

THOM AG AF ows

ii C. Cave, CLER:

ME i

DEPUTY Gl, ERK i ie

JOHN DILLARD, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

Ve CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, etc., et al.,

S

e

?

N

a

N

o

S

N

N

N

N

N

N

S

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM OPINION

This matter is before the court on the plaintiffs' September 11,

1986, request to show cause why the Crenshaw County defendants should not be

held in contempt of court and the plaintiffs' October 7, 1986, motion to

enjoin the November 4 general elections of the Crenshaw County Commission.

A hearing was held on the motion and request on October 31, 1986.

1.

This litigation has involved a number of Alabama Counties wherein

the plaintiffs challenged the at-large election systems of the county

commissions claiming that the systems diluted the voting strength of black

citizens in violation of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42

d8.00 § 1973. The court has previously ruled on various aspects of this

case. See Dillard v. Crenshaw County (Dillard I), 640 F. Supp. 1347 (M.D.

Ala. 1986), and, most recently, the memorandum opinion of this court dated

October 21, 1986. Crenshaw County is one of the counties that settled the

claims brought against it by the plaintiffs.

The Crenshaw County defendants before the court are Jerry L.

Register, Amos McGough, Emmett L. Speed, and Bill Colquett, who are the

present county commissioners for Crenshaw County; Ann Tate, circuit clerk of

the county; Ira Thompson Harbin, probate judge of the county; and ‘Francis A.

Smith, sheriff of the county. Probate Judge Harbin is also sued as a member

of the Crenshaw County Commission.

The plaintiffs and Crenshaw County defendants agreed to a

settlement that required Crenshaw County to utilize five single-member

districts for the election of county commissioners rather than the present

at-large election system; under the settlement, one of the five districts,

district five, has a clear majority black voting population. On April 18,

1986, after notice to the class and a hearing, the court approved the

settlement on an interim basis pending U. S. Justice Department

preclearance of the settlement pursuant to section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act, 42 U.S.C.A., § 1973¢; and, on June 17, 1986, after preclearance, the

court gave final approval of the settlement

Party primary elections were conducted on June 3 and primary

runoff elections on June 24, 1986. All of the incumbent defendant county

commissioners lost in the Democratic primary. The Democratic nominees Billy

J. Sexton, Jerry L. Hudson, Walter Barnett King, Aubrey Alford and John

Bryce Smith intervened as defendants in this action. The circuit clerk,

probate judge and sheriff are separately represented by different counsel

from the present county commissioners. The general election is scheduled

for November 4, 1986. There is only one contested seat for the November 4

election and that is in district five, the majority black district.

iL,

The plaintiffs complain that defendants circuit olorh; probate

judge, and sheriff did not implement the single-member district plan agreed

to in the settlement and ordered by the court for the June primaries, and

that these defendants are not prepared to do so for the upcoming November 4

general election. Basically, the plaintiffs complain that these election

officials never developed a list of registered voters for each of the five

commission districts; rather, they contend that each voter was allowed to

vote in the commission district of the voter's choice.

There is not a significant factual dispute as to how the June

primary elections were conducted. None of the existing beatlines were

changed; rather, the lines of the beats were maintained as they had been in

past years, with 10 of the 15 existing beats split into two or more of the

county commission districts. To accommodate the splitting of the beats, the

number of votings machines at the polling places was increased from 26 in

past elections to 37 for the June primaries. The county commissioners

authorized the probate judge to hire the necessary personnel to develop a

list of registered voters for each of the five districts. The county com-

missioners understood that those lists would be prepared in time for the

June primaries. The commissioners testified that they were not aware that

the work of assigning voters to the correct district had not been undertaken

until they saw the list of registered voters published in a local paper on

May 14, 1986. The commissioners, however, took no action to stop the

primary elections. Furthermore, only one commissioner filed a challenge to

1. Crenshaw County traditionally has used the term "beat" to

refer to the geographical area encompassed by a particular polling place.

Therefore, this order will also use that terminology. The term "polling

place" will refer to the specific location where the voting machines are

actually located.

3

primary elections after his defeat, and he later abandoned the challenge.

The parties, however, dispute the magnitude of the out-of-district

voting. The plaintiffs contend that there was wholesale out-of-district

voting. In contrast, the circuit clerk, probate judge, and sheriff admit

that there was some but claim it was insignificant. The court finds

credible the testimony of the circuit clerk that certain procedures were

specifically implemented to assure that there was no out-of-district voting;

the court is, however, also of the opinion that these procedures were not

completely adequate and that, while there was not wholesale out-of-district

voting, such voting was nonetheless substantial.

11.

The plaintiffs contend that the presence of out-of-district voting

violated the one-person, one-vote requirement of the fourteenth amendment to

the U.S. Constitution, Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 84 8.Ct. 1362 (1964),

and the general single-member district requirement of the consent decree.

Admittedly, it may be true that election irregularities could be of such a

magnitude as to violate the one-person, one vote constitutional requirement,

See Bell v. Southwell, 376 F.2d 659 (5th Cir. 1967), or the general single-

member district requirement of a court injunction. However, while the

irregularities here were substantial, they were not of such a magnitude as

to violate the U.S. Constitution and the general single-member district

requirement of the consent decree and thus to warrant federal court

intervention. The avenue of relief for the irregularities here is and

remains the state process.

111,

The plaintiffs also contend that the out-of-district voting

violated the consent decree's intent to provide the black citizens of

Crenshaw County an equal opportunity to participate in the county's

political process. The court agrees as to district five only.

The plaintiffs brought this lawsuit claiming that the present

at-large election scheme for the Crenshaw County Commission violated section

2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U,.S.C.A. § 1973. They traveled on

two theories: (1) that the at-large scheme, in conjunction with certain

social, economic, political, and geographic conditions, impermissibly

"resulted" in the dilution of the black vote in the county, Thornburg wv.

Gingles, B.S. , 106 S.Ct. 2752 (1986); and (2) that the scheme was

"intentionally" passed to discriminate against the county's black citizens.

Dillard I, 640 F. Supp. at 1353, As already stated, in settlement of the

claims against Crenshaw County and to assure that the black county citizens

enjoyed an equal opportunity to participate in the political process and

elect candidates of their choice, the parties agreed to the creation of five

single-member districts with, most importantly, district five having a clear

black voting majority. The court is convinced that the out-of-district

voting that occurred during the June primaries substantially and

significantly impaired the existence of district five as a clear black

voting majority district; indeed, the court is convinced that it is more

probable than not that with the out-of-district voting district five was

effectively no longer a majority black voting district as intended by the

settlement.

It is also significant that there were two black candidates and

one white candidate in the first primary election for district five, with a

runoff election between a black and white candidate, and with the white

candidate winning the runoff election by only 17 votes. The court is

impressed that, because the election in district five was so close, there is

a strong likelihood that the election of the white candidate over the black

candidate was due to out-of-district white voting.

It is also significant that the irregularities occurred under the

old commission regime, prior to full entry of the county's black citizens

into the political process by the election of a commissioner of their

choice. Under such circumstances, where the democratic process is not yet

racially fair and equal, the judicial deference normally due the process is

not warranted, and a court may more readily step in to cure the

irregularities, especially when the evidence reflects that there is a

substantial likelihood that the irregularities have had a disproportionate

adverse impact on blacks.

In light of these circumstances and legal principles, the court is

convinced that the June primary elections for district five violated the

intent of the consent decree entered into by the parties; the primary

election irregularities in district five impaired the opportunity of the

black citizens in that district to participate equally in the political

process and to elect the candidate of their choice. Because the other

district had only small black populations, the court cannot say that the

same was true for these districts.

=~

The court will therefore

defendants conduct new primary and

before January 1, 1987, with these

primary elections and the upcoming

also require that these defendants

require that the Crenshaw County

general elections for district five

new elections to supersede the past June

: 2 :

November 4 election. The court will

adopt, and file with the court,

procedures that will identify prior to the new elections all registered

voters residing in district five and that will document and assure in

accordance with state law that only registered voters in district five may

vote for the district five commissioner in the new elections.

An order and injunction in accordance with this memorandum opinion

was already entered by the court earlier today.

DONE, this the 3rd day of November, 1986.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE~___

2. Because it appears that there may be some difficulty meeting

the January 1 deadline, the court declines to enjoin the November 4 election

for district five. The court does not want the new year to arrive with

district five left without any representative.