Swint v. Pullman-Standard Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 7, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swint v. Pullman-Standard Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1975. 368640a3-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9a38d53f-4c77-41a8-81c5-3f6cda9b5340/swint-v-pullman-standard-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

/

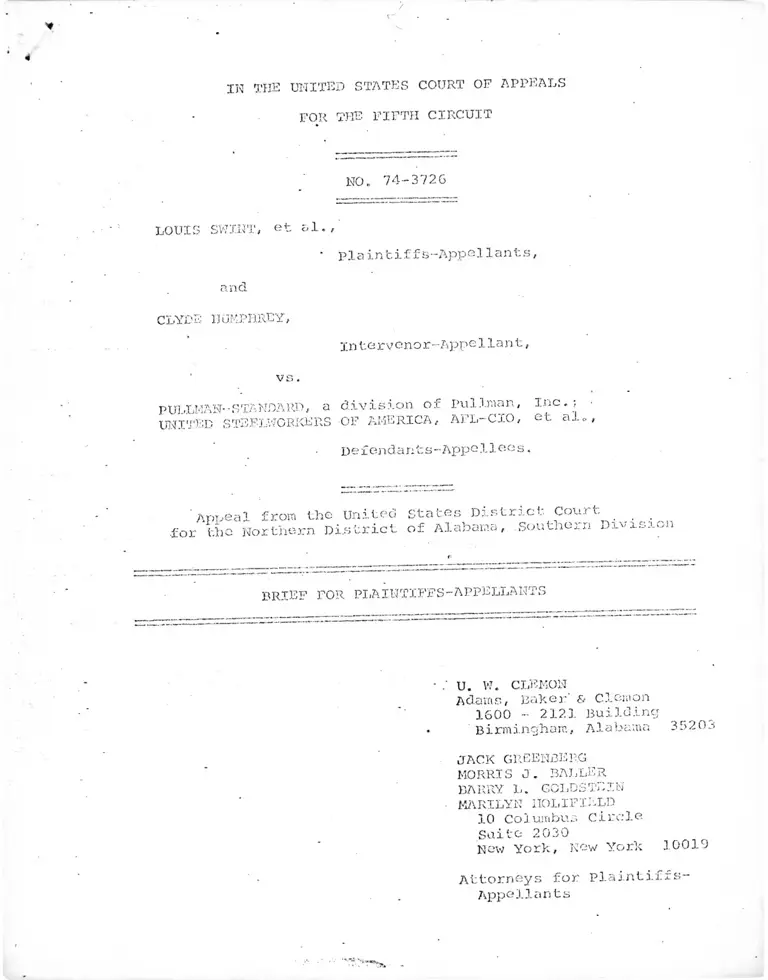

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-3726

LOUIS SV7JUT, et &1. ,

* p 1 a i n c. iff s - App Glia n t s,

and

HUMPHREY,

Intervenor-Appellant,

vr,.

PULLMAN-• STANDARD, a division of

UNITED STEELWORKERS of AMERICA,

Pullman,

AFL-CIO,

Inc. •

st ale. ,

D e f e n d a n t s-Appe11ees.

Appeal frora the United

.for the Northern District

States District Court of Alabama, Southern Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

• U. V7. CLEMONAdams, Baker A Clcmon

1600 - 2121 Building Birmingham, Alabama 3520

JACK GREENBERG

MORRIS 0. BALLER

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

• MARILYN ITOLIFILLD10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for.' Plaintifxs—

Appellants

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-3726

LOUIS SWINT, et al.,

and

CLYDE HUMPHREY,

vs.

P 3. a i n fc i f f s - Appel 1 a n t s,

Intervenor-Appellant,

PULLMAN^STANDARD, a division of Pullman, Inc.; UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court _ _ _

for the Northern District of Alabama, Southern Division

brief for plaintiffs-appellants

statement OF THE CASE

This'case involving racial discrimination in employment is

n appeal from the decision of the United States District Court

or the Northern District of Alabama rejecting in all substantive

espects plaintiffs-appellants' claims of discriminatory em-

,loyment practices on the part of their employer and pertinent labo

inions, defcndants-appellees here. ihis Court hc.s jurisdiction

he appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

plaintiffs-Appellants are three black workers, two of whom

ire presently employed by Pullman-Standard Company and one of

Defendants are Pullman-Standardwhom is a discharged employee.

Company, .the United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO and its

Loca] 1466. By leave of the court the International Association

of Machinists and. Aerospace workers was added as a defendant

subsequent to the filing of the complaint. (R.I.[7] ).

The complaint to this action grew out of a series of

charges of discrimination filed between 1969 and 1970 by Mr.

Louis Swint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

(hereinafter "EEOC"). (R.I.[7) p.4; [4] p.8) This litigation

was timely commenced by the filing of a complaint on October 19,

1971 under Title VII of the civil Rights Act. of 1964 and 42 U.S.C.

§1981. j/

By supplemental pretrial order dated June 5, 19/4, the court

below defined the class represented by the named plaintiffs as

" . . . all black persons who are now or have been employed, within

one year prior to the filing of any charges under Title VII

against the defendant company as production or maintenance em

ployees represented by the United Steelworkers." (R.I[7]) Since

black employees first filed charges on April 11, 1967 2/ the cIass

1/ Plaintiff Johnson's cause of action is premised upon 42 U.S.C.

§1981.' The Court permitted Mr. Clyde Humphrey to intervene as a

party—plaintiff on July 4, 1974. (R.X[/])

0 / On Anril 11 1967 Jessie B. 'ferry, Edward Lofton and Spurgeon

l^als filedcharges o racial discrimination with the Equal Employ- me ^OpportunityCommission against their employer. Pullman-Standard

in":,pLLuant to 42 U.S.C.A. §2000e et seg,, alleging drscrxmaiatron

against blacks in the assignment of work in the paint doparan o ,

the company. (PX 58, 60) In addition, three months oarlier^.„o,,,

Tanuarv 1967), two of the Commissioners of the EEOC had ill-

charges* against the company, alleging the maintenance o tfacilities reprisals against blacks who voiced opposition again..t

unlawfui°employment practices, and discrimination in hiring and pro-

motion. (PX 60)

2

consists of all black persons who are now or have been employed

at Pullman since April 11, 1966.

The case was tried before the Honorable Sam C. Pointer, Jr.,

United States District Judge for the Northern District of

Alabama, in July and August 1974. (R.I[1], P*3) At trial plain

tiffs challenged discrimination-in defendants' seniority system,

job assignments, promotions to salaried positions, lack of job

posting and the' discharge of two named plaintiffs. Following

sixteen days of trial, the district court, on September 13, 1974,

issued its memorandum of opinion. (R.Ifl] , P-4) With virtually

no exception, 3/ the court denied all of plaintiffs' claims for

relief including costs and an award.of attorneys' fees. (R.I [1] ,

p. 34-35)

Notwithstanding its finding that until mid-1965 racial

segregation of jobs at Pullman significantly discriminated against

black employees and the effects thereof persisted over the sub

sequent years, the district court concluded that in 1965,

"there was no pattern of favoritism to whites.- in the

departmental assignments. Indeed on JaalanceJ_bj^_gks

as a group appeared to receive .Tn such assiqnraents. " 4 / (emphasis supplied )

3 / The district court expanded the classes of blacks eligible

for transfer to certain formerly all-white departments, and sug

gested the possibility, though improbability, _of a limited amoun-

of back pay for a few black employees. Tins issue was severed for

subsequent proceedings. (R.I[16], P• 19, fn. 3o)

4/ (R. I [ 16] , p. 11)

3

Therefore the court-found that Pullman's departmental seniority

system did not carry forward the effects of past discrimination,

thus it was not in violation of Title VII; that there was no dis

crimination in the assignment of employees to departments, job

classes or to occupations within a job class; that there was no

discrimination in the use of subjective judgment in the selection

of foremen; that the failure of Pullman to post vacancies neither

-discriminated nor perpetuated the effects of any past discrimination;

and that there was not the slightest evidence of racial discrimination

in the discharge of plaintiffs Louis Swint and Clyde Humphrey. .In./

On September 16, 1974, plaintiffs filed a timely notice

of appeal seeking reversal of the blanket rejection of their

claims. (R.I[1]/ P-4)

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Introduction •I!

The Pullman-Standard company (hereinafter "Pullman" or the

Company") operates a railroad carbuilding plant in the City of

Bessemer, Alabama. The Pullman operation at Bessemer is the

largest freight car manufacturing plant in the world, occupying

an area of 108 square acres. (Tr. 1247) A variety of types of

cars is manufactured at Bessemer; Boxcars, Flatcars, gondolas,

open hopper cars, closed hopper cars, and variations of these.

(Tr. 1229) Orders from the railroad companies vary in size from

twenty-five cars to several thousand cars. (Tr. 1228) Because

of the different sizes of orders, there is a cyclical employment

pattern and lay-offs are frequent. (Tr. 1229) *

4a/ R. I [ 16) , PPS- 20 • 23 • 26, 32, 33.

4

All the production and maintenance employees at the Bes

semer plant are represented by either Local 1466 of the United

Steelworkers of America (hereinafter "Steelworkers") or by the

international Association of Machinists (hereinafter "IAM") .§_/

Within these departments, the Company has not maintained

formal lines of promotion or progression or job to job sequences;

rather employees advance up a ladder of pay groups (£riL_' 3°^

classes) embracing one or more jobs each. Each job or occupation

in the production and maintenance departments is given a job

classification, which determines the base hourly rate of pay for

the job in question. (CDX 263) Steelworkers job classes (herein

after "JC") range from 1-20, with accordingly ascending wage

wages. _6/ With respect to the IAM jobs, job classes are not

utilized; rather a base hourly wage rate is negotiated for each

occu.jpei i* xo n •

in addition to production and maintenance and IAM bargaining

•unit jobs, this case involves salaried supervisory positions, not

represented by any union, into which hourly wage employees

h is tor ical 3.y have been promoted. 5

5 / The IAM is the bargaining agent for employees in the Main̂ .

finance IAM and Die and Tool IAM departments (PX 2, 12), the

maining production and maintenance employees, who work among twenty-five departments, are represented by the steelwork r_.

(PX 10)

r/ The pay rates for the job Classes in 1964 ranged from $2-10

V c 1-2) to $3.36 (JC 20) per hour. In 1973 the pay rates r«i g

from $3.63 (JC 1-2) to $6.39 (JC 20). (CDX 262)

5

1. Historical Segregation of the Departments and Jobs

Pullman employed nearly 2,324 persons in 1965, almost evenly

divided between blacks and whites; (PX 2, 12) however the size

of its work force fluctuates due to the cyclical pattern of

employment at Pullman. Just prior to trial (July, 1974) the

company employed 2,800 workers, of whom roughly half were

black. Ij (PX 10, 20)

prior to 1965, most of the jobs at Pullman were segregated

fcy race. (PX. 2, 12) In the twelve one-race P&M departments

existing in 1962, there were 35 segregated, jobs. (PX 41) In

the remaining sixteen P&M departments, 134 of 148 occupations were

occupied by members of one race only. (PX 1, 11, 41) There

were instances in which certain occupations were occupied by

whites only in some departments and blacks in others. _9_/ The

pattern of racial segregation in'employment is clearly revealed

in the 1964 seniority roster and was confirmed by trial testimony.

7 / in the City of Bessemer, with a population of 33, 42B in 3970,

“52.2% of the total population is black. (PX 216, P--W.

8 / This is based on the seniority rosters verified by the testi

mony of witnesses in deposition and at trial.

JL/ For example, all of the cranemen in Die J Tool I*M^were^ whites

in 1964. in the same year, all of the cr • ‘ dri] x res5 operator

cellaneous department were blacky ( X ) ^ Punch and Shear

in Die and Tool IAivi were wnius, m .departments the drill press was a black occupation. (PX 11)

6

0■ fr

(PX 1-10) As shown below, ].(/ in 1964 over three-fourths of the

jobs in which four or more persons worked were segregated by race.

NO. OF NO. OF TOTAL JOBS

IQ/ department BLACK JOBS WHITE JOBS DEPT. WITH

OR MORE

Air Brake Pipe shop 0 1 1

Die & Tool CIO 2 ' 0 2

Die & Tool IAM 0 5 5

Forge 2 3 6

Inspection 0 1 1

Janitors 1 0 1

Lumber Stores 0 0 2

Mai n tenanee CIO 1 5 10

Mai n tenanc e IAM. 0 2 2

Miscellaneous Stores .0 1 1

Mobile Crane 1 0 1

Paint & Shipping Track 1 3 6

Plant protection 0 2 2

Press 1 2 3

Punch & Shear 2 0 4

Railroad 0 1 2

4Steel Construction 2 1

Steel Erection 2 1 4

Steel Miscellaneous 3 0 4

Steel Stores 3 1 4

Templa te 0 2 2

1Truck 1 0

Welding 0 3 4

Wheel & Axle 2 2 4

Wood Erection . 2 3 8

Wood Mill 1 2 4

27 41 88

IN

4

Source: (PX 12, 42)

See also PX 41, which shows that in 1962 sixty-three (88%)

of the 72 jobs with four or more occupations were filled by

members of one race.

7

t .

a. The All While Departments

in 1964 there were eight all white departments at Pullman:

Template, Power House, inspection, Plant Protection, Air Brake.

Pipe Shop, Die and Tool IAM, Maintenance IAM, and Boiler House.

(PX 2, 12) Not surprisingly these eight departments contain the

highest earning opportunity and/or -the best working conditions

of Pullman's departments. Five of the ten white employees in

Template held JC 18 jobs while the rest held jobs ranging from

JC 12 to JC 16.' (PX 2, 12) The first and only black was as

signed to this department in 1970. (R. PX 7, 17) Despite the

occurrence of several vacancies in the Inspection Department be

tween 1965-1971, it was only after the filing of this lawsuit,

that blacks were assigned to the inspection department , where in

1964 its twenty one white employees held either JC 12 or JC 13

jobs. (PX 1-9, 10-19)

in 1964 the fourteen whites in plant protection held JC C

or JC 6 jobs and no blacks entered plant protection until 1968.

(PX 3-5, 11-15) The first black was not assigned to tliis department

until 1968. (PX 1-5, 11-15) The maintenance IAM and die and tool

1AM departments JJ/ which include approximately sixty jobs,ex

cluded blacks until 1969 and was near totally white at the date

11/ several of the occupations in the all-white IAM die and toolto the forgedepartment (e.cr., drill press, craneman), are common to tnc r

shop tho skcl miscellaneous, steel stores, end wheel and axle

departments - to which blacks were assigned. (PX 12)

8

of trial. (PX 1-10, '"11-20) No black'was assigned to the air

brake pipe shop until 1968; and the boiler house, a single man de

partment, having a JC MO occupation was always reserved for whites.

(PX 1-10, 11-20) These departments were all white in 1964 and

have continued to remain virtually all white. (PX 1-10, 11-20) .jj?/

b. Mixed Departments

Roughly half of the production and maintenance departments

at Pullman in 1964 were mixed - i.e. , both whites and blacks were

assigned to the departments. As of 1965, most of the occupations

in the mixed departments were segregated by race with blacks con

centrated in the lower paying positions. (PX 2, 12)

Included among these mixed departments were the largest

departments of the company - welding (with nearly half [47%] of

all the production and maintenance workers) , steel erection (8% oi.

the employees), paint and shipping tract (1% of the workers),

steel construction (5% of the workers), wood erection, punch and

12 J ■ The racial breakdown of the employees actually working on

May 8, 1973, is as follows:

Department

Inspection

Plant Protection

Power House

Air Brake pipe Shop

Maintenance IAM

Die & Tool IAMTemplate

V}h i te s Blai

11 0

10 1

2 0

io 0

44 5

44 1

2 1

NOTE: Boi]er house was not operating after 1966. (PX 2, 3)

SOURCE: CDX 274, pps. 11-16

9

shear, maintenance CIO, and steel miscellaneous. 13/ (PX 2, 12)

Each of these departments, with three exceptions, had at least

one occupation rated as a job class 10 or above. (PX 2, 12)

With the exception of the welding and maintenance CIO departments,

however, none of the departments had. a significant number of

.employees assigned to occupations rated above a Job Class 7.

(PX 2, 12)

The welding department, the largest production and maintenance

department at the company, offers the most attractive job op

portunities to the greatest number of employees. Occupations

in the department range from a JC 1 (Clean-Up Man) to JC 14 (craft

welder). (PX 12) The overwhelming majority of the jobs in the

welding department (90%) are in Job Class .10 or above and the

median job class 14/ i.n the department is JC 10.

However, a racial breakdown of the job classes in the welding

department in 1964 is as follows:

Job Class Whites Blacks % Black

14 5 0 0

10 1646 0 0

6 4 198 98%

Blacks constituted only 10.7% of this department in 1964. (PX 22)

13 / The wood erection, punch and shear, maintenance CIO, and

steel miscellaneous departments had 100 or more employees each and

together accounted for 15% of the company's production and main

tenance workers. (PX 2, 12)

14 / The median job class is derived from PX 12, by computing the

job class belowwhich exactly one-half of the employees in a department are assigned, and above which exactly one-half of: the employees

in a department are assigned. The mid-point is the median. See

chart infra at 44, showing median job class of departments.

10

Doubtless, Pullman’s rigid policy of excluding blacks from welding

positions contributed to the relegation of Jill blacks in the

department to JC 6, while the 1651 of the 1655 whites in the

department were JC 10 or above.

While the maintenance department CIO has the highest median

job class (e.g., JC 13) of any mixed department, in 1964 only 13%

of the department was constituted by blacks having a substantially

lower median job class (e.g., job class 4) (PX 2, 12) 15/ Con

sistent with defendants' practices favoring whites, between 1964

and 1966, some thirty white employees were initially assigned to

jobs above JC 10 in the department:. (PX 2-4; 12-14) Eight blacks,

however, who were assigned to the maintenance department during

the same period came in JC 2 or JC- 4 positions. Despite the

transfer of five blacks to maintenance in the latter half of

1973 this department remains predominantly white. (PX x-lO, J.1--20,

in the forge department 81.1% (43 out of 53) of the white

workers were assigned to occupations in JC 8-15 in 1964. While

nearly 97.6% of the blacks were assigned to JC 6 and below

15/ in 1964, the racia by job class was as follows:

job Cla ss

18

14

13

12

11

6 •4

il breakdown of the maintenance department

Blacks % BlackWhites

19 0 0

13 ' 1 7

40 0 0

28 0 0

4 0 0

0 3 100

2 28 93.3

SOURCE PX 2, 12

11

occupations. There were no blacks above job class 7 in steel

erection while jc 11 was held exclusively by fifty whites. 16/

Similarly, in the paint and shipping tract 17/ department the media

job class for the department was JC 7, while the median job class

for blacks was JC 6. The departments: railroad, 18/ punch and

Steel Erection

Job Class

1.1

7

6

5

1

Whites Blacks % Black

50 0 0

0 27 100%

13 21.1 94. 2%

0 2 100%

0 1 100%

SOURCE: PX 2, 12

17/ paint and Shipping Tract

Class Wh i. te s Blacks % Black

11 5 0 0

10 4 0 • 0

9 2 0 0

8 1 0 0

7 98 44 30.9%

6 4 22 84.6%

4 29 63 68.5%

SOURCI PX 2, 12

18/ In 1964, the median job class for whites was JC 11; for

blacks it. was JC 7. (PX 2, 12)

12

0

shear, 3,9/ and lumber stores 20/ repeat the motif of racial

stratification within the departments, 2l/ accomplished in part

by practices permitting junior whites to enter departments at higher

job classes than senior blacks. 22/ (PX 2, 12)

19/ Blacks constituted 01.8% of the workers in punch and shear and

held jobs in job class .1-8 only. Whites, however, were assigned to

the two highest occupations, JC 11 or JC 12.

20/ The median job class was JC 3 and was 41.6% black.

The remaining mixed departments - steel stores, wood erection,

and.wood mill are indistinguishable from the steel miscellaneous

department from the promotional opportunities point of view. in

each of them, as in steel miscellaneous, the median job class for

blacks is JC 2; indeed, in steel stores the median job class for

the department is JC 2. While technically the wood mill has one

occupation rated above a JC 9, in fact this occupation was not

worked until 1966 and it was discontinued after 1969. The wood

erection department has one occupation rated above jc 9, but only

two. white employees were assigned to this occupation in 1964, and

only one white employee lias occupied it since that time.

22,/ Between 1965 and 1968, Pullman promoted at least six junior

whites (each having a department seniority date subsequent to 1963

and four of whom were relatives of white foremen) to the hignese

ra ted jobs in the steel erection department without offering these

vacancies to senior black assemblers in the department. (PX 5;

DCS 278; PX 1-10, 11-20) At least two junior whites were promoted,

ahead of more senior black assemblers. (PX 5, PX 7; DCX 278; PX 1-10, 1.1-20) Indeed it was the promotion of a junior white employee,

11. Thomas ton, ahead of senior blacks which was the subject of plain

tiff Swint's original EEOC charge. (PX 5) The court, however,

failed to consider the testimony of a number of witnesses which

verified these incidents.

The racial. breakdown of employees actually working on May 8,

1973 (CDX 274, pps. 11-16) is as follows:

%B in %B in

Dept. B W Dept. Dept. B W Dept.

Welding 113 364 23.7^ M. Stores 6 2 75.

Maintenance 23 80 22.3 W. Mill 1 3 2 5.

Paint & ST 57 34 62.6 Punch & Shr. 46 6 88.5

S. Erection 117 .10 92.1 Wood Ercc. 38 28 57.6

S. Constr. 44 21 67.7 Press 16 5 76.2

Wheel & Axle 7 11 38.9" Steel Strs. 24 3 88.9

Forge 8 16 33.3"

13

c. All Black- Departments

The die and tool CIO department, (JC 6, JC 2), janitors

department (JC 1), and steel miscellaneous department (JC 2-9)

were all black in 1964. The court below found that the company

had continued to discriminatorily assign blacks to the janitors

department until June 1, 1967; that blacks were discriminatorily

assigned to the truck department until June 1, 1968; and that they

were discriminatorily assigned to the die & tool (CIO) department

until June 1, 1971. (R.I[16]) The court, however, disregarded

the fact that these departments -remained intact as essentially

"black" departments as late as May 1973. _23/

d. Other segregated Departments

In addition to the all-white production and maintenance

departments at Pullman, the exempt departments were all segre

gated by race. The thirty-three employees in the accounting

department, seventeen in the manufacturing department, and the

fourteen employees in the purchasing and stores department were

all white in 1966. (PX 12) These departments were still all-

white in 1966. (PX 13) By 1968, there was one black out of

23/

May

The racial breakdown of the employees actually v

1973 is as follows:

Department Whites Blacks

Die & Tool CIO 0 5

janitors 0 9

Steel Miscellaneous 0 50

Truck 0 9

SOURCE: CDX 274, pps. 11-16

14

*

thirty employees in the accounting department; no blacks among

the five employees in the engineering drafting department, one

black and fifteen whites in 'the manufacturing department, and one

black among the twelve employees in the purchasing and stores .

department. (PX 5) As of the date of trial these departments

were in harmony with Pullman's tradition of segregated jobs and

departments and were unmistakably white.

CONCLUSION

The pattern of racial segregation .is crystal clear. Blacks

were totally excluded, from the choice all-white departments.

Those blacks who worked in "mixed" departments were relegated to

the lower paying jobs while the higher paying jobs were reserved

for whites. Indeed, the segregationist barriers against the

entry of black workers into higher job classes or raxxed departments

operated to disproportionately exclude blacks from departments

offering the most attractive employment opportunities,

welding, maintenance). Moreover, the traditionally all-black

departments, to be sure, contained the lower paying job classes

and offered little opportunity for advancement (e_.J2w janitors,

die and tool CIO).

2. Promotion And Transfer Practices And seniority

Pullman has never had a systematic procedure, which includes

written standards, for filling job vacancies. In theory promotions

to vacant jobs within a department go to the most senior qualified

person in the department. (PX 71) According to the local union

rules, seniority is determined by the length of continuous service

15

in a particular department and is exercised in competition with

all other employees in the department. (CDX 262)

There are no standards governing the determination of an

employee's qualifications, and there is no set length of time

an employee must work in a higher occupation before he is shown

on the seniority roster as being qualified and entitled to work

the occupation. (PX 71) Vacancies are not announced or pub

lished. (CDX 262)There are no lines of promotion or progression

in any department, and job class levels govern promotions. (PX

71)

Departmental age is used to determine who is promoted or re

called (assuming the ability to do the work) in the event of

vacancies or who .is rolled-back or la id-off in the case of

reductions. (CDX 262) Department heads (all white) are ultimately

responsible, for determining which employee obtains the promotion.

(CDX 262)

The company maintains a seniority roster listing for each

department, reflecting the name, badge number, seniority, and.

occupation of each employee assigned thereto. (PX 1—9) These

rosters are updated annually; and each roster covers the period

of June 1 of one year to May 31 of the following year. (PX 1-9,

Tr. .14) The occupations listed for an employee on the seniority

roster indicates the highest job.on which the employee has quali

fied. Once an occupation is listed on the seniority roster op

posite an employee's name, his ability to perform the job may not

thereafter be questioned and he is entitled to the job ahead of

all other persons in' the department except senior employees in

the same occupjition in the department. (Tr. 1730, 1/31, 1 /32,

17 30)

16

In other, words, to the extent: that work is available for a

particular occupation, the employees whose names appear on the

seniority list in the said occupation are entitled, to- work the

job on the basis of their department seniority, and before an

employee can exercise his plant seniority on a job, he must have

attained that job - using department seniority. While an employee

will frequently work in an occupation below that shown for him

on the seniority roster, the occupation listed for him on the

seniority roster represents the very highest occupation to which

he is entitled, assuming available work. The seniority desig

nations indicate the predominant occupation of employees during

normal periods of employment. (CDX 2.74, p.!0)

For those j c 's, particularly the higher JC's, in which few

to no black employees are listed, it is clear that blacks were

not deemed "qualified" for those'positions and thus did not have

an opportunity or contract right to work in .them.

Foremen's discretion regarding the assignment of employees

to temporary vacancies is extremely important: in the acquisition

of qualifications required to perform in a higher job class. The

evidence shows and the district court found that temporary pro

motions, while affording some increase in compensation, provide

"the principal avenue by which an employee can obtain recognition

beingas/capnble of satisfactorily performing the job." 24/ (CDX 264)

24/ (R.I. [16] p. 5 n . 14

17

At Pullman, foremen have absolute discretion, subject to

no written constraints, to assign employees to temporary vacancies

of three days or less.’ (0X254) Three day temporary assignments

therefore can be made by foremen in complete disregard of

seniority or other standards, and the union contract does not

permit employees to grieve these temporary assignments. (PX 71)

Whenever an employee transfers from one department to

another, except on the orders of management, the transferee re

linquishes seniority in the department from which he transfers

and enters the new department as a new man. (PX 71, "Local

Working Conditions", pp. 1-2) Consistent with classic.depart

mental seniority systems, the transferring employee does not

carry over any of his accumulated seniority for promtion, re—

duct ion in fcicc, oi Didain^ purposeo* ^j. ^

wage progression structure and transfer practices, it is almost

a certainty that a transferring employee moves from a higher to

a lower paying job. (Tr. 1/67) in general, Pullman does not

provide for protection of the transferring employees' wage rate.

IX 71) Thus, in ordinary circumstances, an employee who had pro

gressed any significant distance up the wage group schedule in

one department and then transferred to a different department, in

order to improve his chances for eventual advancement, higher

pay, or better working conditions, can expect to be required to

take a wage cut as a condition of transfer.

3. Discriminatory Assignments of Jobs Within the Same job Class

Prior to 1965, it was an admitted policy of the Pullman company

10

to segregate its occupations by race. The record further-

established that, for the most part, blacks were assigned to

the least desirable, least remunerative occupations. (AI, No.

32) The all-white foremen, whose duties included the assignment

of workers, implemented this discriminatory policy.

These foremen have absolute discretion to assign work among

employees working in a given job class in a department except

for welding. (WHD, p. 59)

With one exception, the seniority provisions of the contract

do not apply with respect to assignments of work in occupations

in the same job class. The exception to the ordinary pattern

of job assignments at Pullman obtains in its largest department,

welding. ' in this predominantly white department covering nearly

half of the company's workers, employees are entitled to bid on

job assignments for all car orders of 100 cars or snore. (CDX

262, 263, "Local Working Conditions") Because blacks were ex

cluded from the welder occupation in the department prior to

1965, and nearly all of the jobs therein are welder I jobs, the

b iddi-ng system here admittedly results in whites choosing the

best welding jobs. 2d7 Employees of the Pullman plant at Butler,

Pennsylvania also exercise seniority to select job assignments

2f/ By the same token, if this system were instituted in the

sTeel erection department, to which pre '65 whites were assigned

only to the relatively few jobs in JC 11, blacks would have the

edge in choosing the most desirable jobs. See also R.I. [16] p. 26

n. 44.

19

at the beginning of each job. (PX 206, p. 3, 9, 15, 19, 22, 25, 27,

31, 32)

in the pro-1965 era, the foremen of the company admittedly

exercised their discretion arbitrarily to exclude whites from

certain occupations in the various departments. (AI, No. 32;

PX 57) The company has listed some forty-two occupations to

which the foremen had never assigned whites prior to 1965. (a .l,

No. 32) 26J In the absence of objective standards requiring

otherwise, foremen can and do continue to arbitrarily exercise

their discretion to maintain the status quo as of 1965.

The paint department furnishes perhaps the most vivid examples

of the arbitrary abuse of discretion to exclude blacks from more

desirable jobs. Prior to 1965 the spray painter occupation (J'C 6)

was an all-black one. (AI No. 32, Tr, 887, 889) This job is

unquestionably one of the least-desirable at the company. To

ward off some of the most dangerous features of their working

conditions, spray painters must grease their faces, hood their

heads, and wear uniforms and respirators while spray painting,

inter alia, the undersides of railcars. (Tr. 171, 888, 1342, 1343)

9r/ bhnrtlv before trial, the company amended its earlier answer

Tr/.hi? interrogatory to show that whites had, at one time worked

ebvenkf the previously listed 42 4iphlach occupations Tnr^_

in ftelwo's whites and blacks had worked some occupation,

iSich had reverted, by the late 1940's, to one-race occupation...

(CDX 288, 289, 290)

-• 20 -

r

c

The stencillers' job, a cleaner occupation in JC 6, remained

until 1970 an all-white job. (PX 6, 16, PX 58, p. 9; Tr. 158,

59, 167, 176, 341, 889, 901) The spray painter helper's job

(JC 4) is basically a black job; the stenciller helper's job

(JC 4) is a white job. The EEOC investigator found

" . . . that the work of the stencillers and

stencil helpers was markedly cleaner than that

of Spray Painters and Painter Helpers. These

differinq condItions were particularly evident

TrT~[The fey e'f 'of pa i n t fumes and particulates

in~~the '' a j r~.~~ The physical appearance of Spray Painters and Painter Helpers also contrasted

to that of Stencillers and Stencil Helpers.

The former were covered with thick coats of

paTnt7"~whi'i~The~Ta~tte~r were" relatively free

of parnt7~r "(PX 60) (emphasis supplied)

As of 1973, 2 7 / 16 of the 19 stencillers were whites -

five of whom have been appointed since 1966; 24 of the 31 spray

painters were blacks. (PX 10, 20; Tr. 166)

In the steel erection department, senior black riveters

are frequently asigned the undesirable job of. riveting the

tar-covered, roof of railcars ahead of junior whites. (Tr. 442,

454, 457, 473, 483, 13.14-1319, R. Tr. 50) White foremen have,

on occasion, removed senior black riveters from more desirable

jobs and replaced them with junior whites, pretextually due to

the white riveter's alleged greater experience on the job, his

aged, condition, and/or his kinship to the foreman. (e. g. , Tr.

454-55, 471-73; R. Tr. 46-48)

2_1 /the

Of the employees actually working as of May

stencillers were whites. (CDX 274)

8 , 1973 all of

21

In addition to the work in the shear room of the punch

and shear department being physically heavier than that in its

punch room, the incentive rates for the machines in the shear

room are lower than those in punch. (Tr. 55, 56, 1389, 1390)

As late as 1970, all of the 26 shear operators were black. (PX 7,

17) The white foremen in the punch and shear department have

passed over, at best, and at worst, denied senior blacks an

opportunity to train for the traditionally white machines in the

press room, while affording such training to junior white employees.

(Tr. 56, 103, 104, 105)

Similarly disparate job assignments are made by foremen in

the forge department, one of whom determines the qualifications

of blacks to perform certain jobs by physical observation (Tr. 131,

122-127; PX 1-19; AI, No. 32); the wood erection department

(Tr. 194-195; PX 1-20; AI, No. 32); and on orders of less than

100 cars in the welding department. (Tr. 201, 202, 686, 756-/61;

R. Tran. 210-212)

4. Rcicial Discrimination In Selection For Supervisory Positions

The department heads ("C" foremen') at Pullman select the tract

supervisors ("B" foremen), production foremen ("A" foremen), and

the hourly ("temporary") foremen. (PX 1-10; WHD, pp. 3 5-40) In

turn, the department heads are chosen by the plant manager and

superintendent. (WHD, p. 36) Prior to_,1965_, t^j^.had^ji^crj3Gcn

a black foremen at Pullman, in any of its....depâ buen'ts. In 1966,

the company promoted its first black to the position of salaried

.foreman. (PX 33) In that year, there were 142 white foremen. (PX

' s i

Four years later, there were 9 black salaried foremen and 151

white salaried foremen at the company. (PX 38) At that-time,

there had never been any black tract supervisors or department

heads; and with the exception of one black tract supervisor out

of a total of 25, the situation today remains much the same.

(PX 10; Tr. 2399, 2400)

The department heads select tract supervisors and production

foremen from the ranks of Pullman's hourly workers. In their

selections, these department heads exercise complete discretion;

with no objective criteria controlling the exercise of such dis

cretion. (WIID, pp. 37-38) Not infrequently, the white foremen

choose their relatives in hourly jobs to fill foremen vacancies.

(Tr. 35, 209, 402, 472-476, 521, 1058; R. Tr. 6-7; PX .10) Hourly

employees are not notified of vacancies in foremen positions.

Qualifications for supervisory positions have never been

articulated by the company. The lack of formal education presents

no barrier to the promotion of hourly workers to such positions

at Pullman. In commenting on testimony regarding the apparent

illiteracy of one of the white foremen (Tr. 404, 405), the depart

ment head, himself having completed th'e ninth grade, (Tr. 2410) ,

stated:

"Q : (by Mr. Stelzenmuller) Do you have - youhave some people of limited capabilities

that way, don't you?

A: (by Mr. Moss) Well, that's right. Townsend

don't have too much education but he has got

a lot of car building experience. I got two

blacks at this time don't have much education,

got a lot of car building experience, they

are good foremen." (Tr. 2371)

23

The record is devoid of any evidence from which it may be

inferred or concluded that blacks are unfamiliar, in any respect,

with the range of job skills necessary for the performance of

supervisory duties.

Blacks in thirteen departments have never been offered either

28_/~

temporary or salaried foremen positions.

Blacks have on occasion worked as temporary or salaried

foremen, and have never refused promotions to temporary foremen,

in the punch and shear, steel construction, wood mill, wood erec

tion, and maintenance CIO department. (Tr. 31, 842, 3340; CDX 278,

338)

In 1973, for the first time eleven blacks were offered tem

porary foremen jobs in the truck department. Nine of the blacks

refused the offer. (CDX 2 78) The hecid of the welding department

testified that six blacks have refused promotions to temporary

foremen (Tr. 2986-2988), but two of the six have subsequently

accepted promotions to salaried foreman and a third to a temporary

foreman. Numerous other blacks have accepted temporary foremen

vacancies in the welding department. (CDX 278)

Company records indicate that only three blacks have declined

to fill temporary foremen vacancies in the steel erection depart

ment. (JMD, 35, 57, 58; CDX 278) Two of these have accepted such

promotion on subsequent occasions. (CDX 278) One black in the

28 / Forge, wheel and axle, plant protection, janitors, press, air

brake pipe shop, die and tool.CIO, lumber stores, power house, mis

cellaneous stores, inspection, maintenance JAM., and die and tool IAM.

(Source; PX 1-10, 31-40; CDX 278, 286, 334) Six of these department

are the traditionally all whi.te departments; two of the departments

arc* flie all-black departments.

24

paint department has refused a temporary foreman's job. (CDX 278)

Although white hourly workers are frequently transferred

from an hourly job in one department to a salaried foreman's job

in another (PX 7; LSD 24; Tr. 043, 2870, 2871,- CDX 334; 1-ID 10, 14),

the few-blacks chose■n as foremen are largely assigned to the pre

dom.inately black dep.artments in which they have worked as the

following chart indicates :

ASS IGXPLENT OF BLACK FOREMEN (1973)

No. of Black %

Black Total of Total

Department % B1a ck Foremen Foremen Foremen

Steel Erection 72.9 5 16 31.25

S to e1 Misce11aneous 62.6 2 12 16.67

Punch & Shear 67.2 2 16 12.50

Welding 2 9.4 2 34 5.88

Steel Constructi on 83.0 1 9 11.11

Paint 49.5 1 11 9.09

Maintenance CIO 25.0 1 15 6 .6 7

All Others 0 162 8.64

(SOURCE: PX 30, 40)

The company's discriminatory selection procedures continued

unabated, until this suit was filed. At least 59 vacancies in

salaried foremen positions at Pullman have occurred since 1966;

blacks have been chosen to fill twelve of these - 4 out of 41

vacancies in the 1966-69 period, and S out of 12 vacancies since

this litigation was commenced. (CDX 282, 334; R. I [16] p. 29)

25

5. The Discriminatory Effects Of The Failure To Post Vacancies

The failure of the Company to post vacancies in any department

other than the one (Welding) containing nearly half of its workers

has created a situation in which any employee ascertains the

existence of a vacancy by after-the-fact observation (i.e., seeing

a new face on the job.) (Tr. 143-147?- Ans to Interrogatory 39(a))

With the frequent lay-offs at Pullman, the constant vacations, ill-

necces and management transfers ordinarily to be expected in a

work force of some 2500 employees, the expectation that employees

will ascertain the existence of vacancies by self-help alone is

far from realistic. The Matthew Hunter experience is illustrative

of the problem. Hunter, a pre-'65 Forge Shop black confined to a

JC 4 occupation, commenced in 1965 to move up to the all-white

craneman (JC 9) job. Some nine years later, after observing a

younger white employee on the crane'within the grievance period,

he grieved his foreman's disregard of his seniority and ultimately

received the job as craneman. (Tr. 124-131, 143-146, CDX 278)

In the interim, several younger whites had been placed on the

2 9/

craneman's job by the foreman.

29/ Spurgeon Seals, a pre-'65 paint department black, has sought

a" tool repairman's job for nearly a decade. (Tr. 165) Yet several

vacancies have occurred since his initial request, and with one

exception, they have all been filled by younger whites. (Tr. 165,166) Louis Pinkard in steel.erection has constantly requested a

riveter's job? but he has been passed over in favor of several

junior whites, with no explanation. (PX 10; Tr. 1214)

Junior Wormley, a pre-‘65 black assigned to the steel erection depart

ment, has sought to transfer to the predominately white maintenance

CIO department. Since vancancj.es in the department are not posted,

Wormley today remains in steel erection while severeil vacancies

26

As late as the most recent seniority roster and Contract

Compliance reports, (PX 10; CDX 282) white foremen continued to

assign junior whites to higher-rated occupations ahead of more

senior black employees. In 1973, a white helper (JC 4) in the

punch and shear department, entered as a wheel borer

(JC 9), and thereafter became an axle grinder (JC 10). (PX 10,

CDX 282) This white employee leapfrogged over eight more senior

blacks in lower occupations and the wheel borer and axle grinder ^

jobs were not offered to these blacks. (PX 10; CDX 278; CDX 282)

6. Changes In The System Of Segregated Job Assignment

a . The Arbitration Awards

Pullman's first steps to ease the rigid system of racial

segregation were triggered by an arbitration decision issued

March 23, 1965, sustaining the grievance of throe black buckets.

in the steel erection department who sought promotions to the

• traditionally white positions of riveter. In ruling m favor of

2 9/ (cont'd)

have been filled in the maintenance CIO department. _ (Tr.. 1004) At

an earlier date, due to the non-posting of jobs, a junior whi c

(nephew of the foreman) had been placed in the higher rated jo

which he had previously on a temporary basis. U r * 513

30/ other forge shop examples include a white drill press opc.raboi

TJC 8) who in February, 1973 moved up to a Job_Class 9 occupation - upsetter operator, bypassing at least fryo senior blacks pome w -

as many as twenty years of seniority). (CDX 2,8, CDX 28 , 'R Brook, a white wheel, recorder, (JC 4) became an axle centercr,

drill and tapper (JC 8) in November, 1972 ahead of live senio

blacks who were not offered the job (PX 10; CDX 2/8; CDX 282)

27

1

the black workers the arbitrator noted:

"No colored man has ever held the job of

Riveter. In spite- of this non-discrimination provision [referring to Section III D7 of the

collective bargaining agreement], there con

tinue to be jobs known as "white jobs" and other

job s known as "colored jobs." . . . The existing

situation must be faced; evasion is no longer

possible in view of the Contract and the laws

recently enacted. "

(UDX 508) (emphasis supplied) (PX 7)

After an award sustaining a. similar grievance by. black welder

helpers, Pullman initiated a series of trial tests to determine

the blacks qualified for the exclusively white welder's position. 3

No blacks passed the trial test. Pullman, upon opening

the) welder's job to blacks, instituted the requirement of formal

welder training as a prerequisite for even taking the company's

welding test despite the fact that whites were previously per-

31/mitted to learn to weld on the job without the requirement of

formal training.

fo . The OFCC Agreement

Pullman in May 1972 entered into an affirmative action pro

gram with the Office of Federal Contract Compliance of the United32 /

States Department of Labor (hereinafter "OFCC") (R.i.[16]).

The unions were not parties to the agreement, and as found by the

31 / (R.I.. [16] p. 6) n.16.

32/ Despite the fact that this suit was pending, plaintiffs were

not consulted regarding any of the negotiations or'provisions of

the agreement.

32a/ R.I[16] p.6 n.16

28

court, the unions never adopted the cxgreeraent. (R.I[16] )

Further, failure of the company to comply with provisions of the

agreement docs not necessarily constitute a violation of the

agreement. (R. i[16]) At any rate, the agreement purported to

compensate blacks hired prior to April 30, 1965, who had un

deniably suffered from Pullman's blatant policies of racial dis

cs imination -

(]) Transfer Provisions Under The Agreement

Under the: agreement, members of the: affected class were given

the right to transfer to any other department at the company, upon

the occurrence of a vacancy. (R.l.[16]) The agreement however does

not require Pullman to post vacancies. .(R.T.[36] ) Transferring

affected class members are entitled to utilize their plant seniority

in the new departments for purposes of promotions, layoff and

recall, except where a transfer is made to a department over which

IAM has "jurisdiction, plant seniority may not be used foi promo-34/

tional purposes. (CDX 2 727, pp. 2, 3, 9) The urfected class

member may choose to retreat from a new department to his former

department, in cases of layoff, dissatisfaction with the new job,

or an inability to promote in the new department. (CDX 2 72, 3, 4, 10)

33 /

33/ There is no evidence in the record that the unions, at anY time, acknowledged or verified, in practice, the validity of^the

agreement. Of the few blacks (less than five) who transferred

under the agreement, the seniority rosters indicate that they forfeited their plant seniority and entered the departments as

"new"ivion. ( PX 3.-10)

34/ Affected class members who transfer to IAM departments forfeit

.their retreat rights after their'pension funds have been released

by the steelworkers to the 1AM. (CDX 2/2, p. 10)

Upon a transfer to the virtually all white IAM departments

(maintenance JAM, die and tool IAM), affected class members,

indeed like employees outside the purview of the agreement, must

forfeit accrued seniority and enter’ the department as new men.

The .1972 agreement contained no provision for rate retention

hence transferring employees were given no assurance that, upon

the transfer they would riot be required to move into a lower job

classification or otherwise lose pay as a result of the transfer.

The agreement does not require Pullman to use job related,

written standards to determine the qualifications of .AC's who

transfer to new departments. Those blacks transferring into the

traditionally white departments are, of course, subject to

standardless determinations of qualifications by white department

3J3 /

heads.~ Thus advancement to higher job classes once the transfer

is made continues to depend significantly on the whim and fancy

of the near totally white supervisory staff. Similarly job

assignments within the job class are governed by no written

standards and white foremen have unlimited discretion. Indeed,

the failure of the agreement to include provisions for the pro

motion of blacks to foremen positions leaves untouched a critical

dimension of the promotion framework.

35/ Under the agreement temporary vacancies for each month are

to be made in a manner that reflects the ratio of blacks to whites

in the departments as a whole. The failure to give a preference

to blacks means that the effects of the lop-sided ratios of the

departments will be embodied in the temporary vacancy ratios,

provided by the agreement.

30

(2) The Scope Of The Affected Class

For purposes of the agreement, the "affected class" of

employees was limited to workers employed by Pullman prior to

April 30, 1965 and assigned to the janitor, die and tool CIO,

truck and steel miscellaneous departments (CDX 272). Not included

in the affected class, an! therefore not granted any rights under

the aereement, were black employees, hired before April 30, 196536 /

into other low ceiling "black" departments and into inferior

black jobs in supposedly "mixed" departments, or any blacks

hired after April 30, 1965, even those hired into departments

which remained predominantly black or all black and those hired into

black jobs in "mixed" departments. Consequently, of the more than

a thousand blacks (i.e., 1200-1300) who were disadvantaged because

of Pullman's discriminatory policies, only 105 black employees

were included in the affected class as denned by the agreement.

(3) Implementation Of The OFFC Agreement

The company under the agreement was required to list all

affected class members (hereinafter "ACs") hired and to offer the

ACs an opportunity to transfer, in order of plant seniority, to

the formerly all white departments in the steelworkers1 bargaining

unit: template, power house, inspection, air brake pipe shop and37 /

plant protection, as vacancies occur. The transferring ACs

36/ E.g., steel erection.

37/ The agreement placed no obligations upon the company requiring

it to provide ACs with carry-over seniority to "mixed" departments.

- 31 -

/

wore not required to forfeit accrued seniority, however there

was no assurance that upon transferring the ACs would not be

required to move into a lower classification or lose pay as a

consequence of the transfer. (Tr. 1767)

Only on one occasion, December 1973, since the agreement was38/

entered has the company notified ACs of possible vacancies.

(CDX 279; Tr. 1570) The affected class members were informed

that the company planned to increase production in early 1974, and

that work would possibly be available in other departments..

39/

(Tr. 1570)

In fact, the Contract Compliance Officer, in response to the

court testified, "I imagine they [ACs] understood they could lose

money shortly after the transfer." (Tr. 1767, 1768) Not sur

prisingly, of the affected class members who were informed of the

impending vacancies, 65 refused the tentative offer to transfer

4 0 /

to the steel erection department (CDX 279) One AC however,

indicated a desire to transfer, and two others actually trans

ferred to the welding department on their own initiative, apparently

38/ Black employees, not within the ambit of the agreement, have

never been formally notified of the terms of the agreement nor cf .

vacancies at the plant.

39/ The record does not disclose- any effort by the Contract Compliance Officers to inform ACs of vacancies, as they occurred in

other departments.

40/ Steel erection was traditionally black, except for the riveter

and tool repairman job. Further, more than fifty persons in steel

erection had twenty-five years or more seniority while the great

majority of the invited transferees had less than 25 years seniority.

Hence there was substantial vulnerability to roll-backs in case of

a reduction in force.

32

entering welding as "new" men. (CDX 279, PX 10) In sum, the

record discloses that less than five black employees, have opted

to risk the loss in pay, the possibility of elusive advancement,

and in some cases, the threat of roll-backs and transfer under

the agreement.

41 /

(4) Failure Of The Agreement

AJ.though its purpose and design was to remedy past discrimina

tion, the agreement's results show minimum change in the status

of black employees gene.ra3.ly and affected class members in par

ticular. As of the date of trial more than 95% of the black

employees were in the same racially stratified dcp

classes as before the agreement became effective,

not improbable since at the time of trial some 22

retired, reducing the class to 83 black employees

greater than a thousand blacks in the work force,

limited relaxation on the risks to transfer (i.e.,

artments and job

This result is

of the ACs had

out of the

The agreement1s

no rate

retention) coupled with the exclusion of "mixed" and JAM depart

ments; the lack of effective provisions for publication of

vacancies; the omission of provisions "regarding the promotion of

blacks to foreman positions; and its failure to include written

job related standards to determine qualifications of employees42/

for the purpose of promotions, resulted in a mere handful of

43 / The Contract Compliance Officer testified that the company did

not subsequently offer to any blacks, including ACs, an opportunity

to transfer to other departments under the terms of the agreement.

.42/ Promotion standards and access to proper work experiences are

of particular importance to the black worker transferring to a

traditionally white department or job class. Sec n. 24 .supra at 17

33

transferees and virtually no progress toward the dismantlement

of racially imbalanced departments and job classes at Pullman.

7. The Discharges Of Louis Swint And Clyde Humphrey

Louis Swint started working for Pullman in 1964 and until he

filed his first charges with the EEOC against Pullman, he had had

no real trouble with the 'company. (Tr. 1054-1060) This charge

was prompted by the foreman's recall and subsequent promotion of a

junior white employee, nephew of a foreman, ahead of Swint.

(Tr. 1059-1061) After filing the charge, Swint became a member

of the Union-Company's Civil Rights Committee, where he persisted

in raising issues of racial discrimination. (Tr. 1078-79; AI. 79,

Exhibit "K") For two years after his initial EEOC charge, Swint

was harrassed by his supervisors, and finally he was fired, pre-

textually based on his entire record. (Tr. 1065-1079; PX 79; PX 00)

Clyde Humphrey likewise began his work at Pullman in 1964.

(Tr'. 975) He was fired after filing EEOC charge against Pullman

alleging verbal abuse by white foremen. (Tr. 975-987) Though

an arbitrator's award required his reinstatement, it did not

require the company to pay his back wages. (Tr. 986, 987)

The EEOC found that the company has on occasion taken reprisal's

against an employee who sought the address of the EEOC. (PX 58,

p. 11)

34

0■ f

ARGUMENT

Introduction

The discriminatory employment policies ana practices presented

for review in this case involve well established principles of

law in a factual context quite common to an industrial employer

based in a southern location for more than thix'ty years. Con

sistent with the commands of custom, the operations of Pullman's

Bessemer plant were segregated by race, with blacks confined to

less desirable jobs and departments offering less pay and ad

vancement opportunities. Even when blacks were located in pre

dominantly white departments, compliance with tradition resulted

in the relegation of blacks to the more menial and lower paying-

job classifications. Despite the company's renunciation of formal

barriers to equal employment opportunities for blacks, the

system of segregation was maintained and reinforced by the near

totally white supervisory staff, the use of a departmental

seniority system, the reliance on word of mouth notification of

job vacancies, discriminatory job assignments and the failure of

defendants to engage in effective affirmative remedial action.

The District Court Erred In Its Conclusion That Pullman's Departmental Seniority System Was Lawful

Pullman has continuously maintained the typical departmental

seniority system which requires any employee, who changes

departments, to forfeit all his department seniority for purposes

- 35 -

of promotion. 43y as this Court so clearly mandated in its land

mark decision, Local .189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir.

1969) cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970), a departmental seniority

system imposed on a prior policy of racial allocation of jobs is

an unlawful employment practice.

"Every time a Negro worker barred under the old

segregated system bids against a white worker in his job slot, the old racial classification re

asserts itself, and the Negro suffers anew for his

employers' previous bias." Id. at 988.

Sea also Rodricfuez v. East Texas Motor Freight, 505 F.2d 40, 61-63

(5th Cir. 1974); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398

(5th Cir. 1974); Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., 491 F. 2d

1364 (6th Cir. 1974) ; United States v. Dothlehem_ 446

p. 2d 652 (2d Cir. 1971); United States v. United States Steel Corp.,

371 F. Supp. 1045 (.1973) ? United States v. Hayes International, 456

F. 2d 112 (5th Cir. 1972); United States v . Jacksonville Terminal,

451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1972) cert, denied 406 U.S. 906 (1972);

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971), cert. di_s-

rnissed 404 U.S. 1006.

The district court denied seniority relief on the ground that

there was no past or present discrimination at Pullman; therefore,

the departmental seniority system was not in violation of Title

VII. The lower court's finding of no past or continuing dis

crimination is neither supported by law or the evidence in the record

!?_/ See P* 13, supra.

36

The court Belov; Erred In Its Determination That The_Maintenance

Of One-Race Departments At Pullman Was Not A Violation Of

Title VII

In complete disregard of the firmly established doctrine

that "separate but equal" offends the Constitution ana laws

' 44/against racial discrimination, . the district court, in full

view of facts showing separate and unequal one-race departments

45/

at Pullman,"" found the company to be free of any unlawful

discrimination in this regard. (R.I[16] p. 20) Essentially, the

district court found, despite the undisputed existence of one-race

departments at Pullman, that: (1) departmental segregation before

X9G5 did not deprive blacks of employment opportunities; (2) that

racially discriminatory assignments to departments ended by June

1, 1971; and (3) that the OFCC Agreement, effective May 2, 1972,

sufficed to eliminate all continuing effects of past departmental

segregation.

The view of the district court contravenes rulings of this

Circuit which have consistently held that statistics showing

racially disproportionate work units constitute a prime facie

case of Title VII violations. united Stcttes v. Jacksonyxl_lc_

Tenn.inal Co. , 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1.971), cert, denied, 406 U.S.

906 (1972); United States v. Hayes International, 456 F.2d 112

(5tli Cir. 1972); Rodriguez v. East Texas Motor Freight, 505 F.2d

supra at 53-54 (5th Cir. 1974) where before 1965, the one-race

44/ Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, 495

‘(1*954).'

45/ See pp. 8, 14 , supra.

417

37

' l

departments constituted a part of a formal system of racial

segregation and the "black"' departments were undeniably inferior,

a presumption of such illegal discrimination continues until the-

racial exclusion reflected in "lop-sided" ratios is eliminated.

Id.

The evidence in the record plainly establishes that one—iace46/

departments persisted at Pullman until June 1973. The district

court, however,, failed to acknowledge that the existence of one-race

departments constitues a prima facie ease of unlawful disenmina-

47 /tion.— From that error, the court below proceeded to conclude

that the departmental seniority system which tended to lock black

employees into the "black" departments by its failure to permit

transfers with carryover seniority and wage rate retention was

without unlawful dimensions.

46/ >ee pp. 23, supra.

47/ The Court's finding that the predominantly one-race depart-

ments were "closer in 1973 to the racial ratios of the plant, as a

whole" is unsupported by the evidence in the record or tnxs case,

in reaching this conclusion the Court relies on certain charts,

not presented in the opinion or entered into the record of this

case. The failure of the Court to include this and other unreproduced charts in the opinon or to append them as supplements to the

record, seriously frustrates the efforts of plaintiffs on tnxs appeal! in that plaintiffs are cut off from discussing and pointing

out to this Court the manner in which the charts are defective or 1

rebutting- assumptions of the unappended charts. Plaintiffs therefore

submit that the unreproduced charts and the findings therefrom must

be disregarded.

38

It is virtually impossible for past and presently segregated

black employees to remove the shackles of Pullman's discriminatory

practices and obtain their "rightful place" in "white" departments

and job classes. To be sure, Pullman's various unlawful practices

all conspire to produce this result. The most familiar of the^e

practices, however, is the departmental seniority system.

Both of the lower court's holdings were in error and must

be reversed.

The District Court's Conclusion That Pullman's Employment

Practices Favored Blacks In 196b Is Without Support In The

Record And Is Grounded upon Ill-Founded Assumptions Of

Its Chart

In view of the undisputed evidence of racially segregated

jobs and departments at Pullman, the district court concluded,

"Indeed, until mid-1965, such practices

[segregation of jobs] signifrcantly discriminated acjainst: black employees; and

the effects thereof lingered with diminish

ing extent, over the following years. 1 41k/

Despite this finding the Court, in the same breath concluded

that, except for the one-race departments, "the evidenc_e_dojes_

not indicate any past or present policy of ragial_ly_.- 4y"/

assignments." (emphasis supplied) Notwithstanding iu->

unequivocal finding of racial segregation at Pullman and the

resulting relegation of blacks to inferior Departments and joo_>,

the Court's separate arrangement of some of the facts of this cas<

in various charts, only one of which is reproduced in the opinion,

jHK R. I [ 16] p. 16

49/ R. I [ 16] p. 20

5 C/ S e e 110 6 0 4 7 , s u p r a , a t 3 8 ,

- 39 -

50 /

caused it to reach this remarkable conclusion. An ex am i n at ion o f

the court's arrangement of these facts, therefore, is crucial.

The chart reproduced in the opinion purports to represent

a ranking of departments' desirability in terms of earning

potentials as well as the accumulation percentage of employees

in the departments. In an accumulating percentage chart, unless

the ranking is reasonably free of defects, necessarily the

"accumulations" will result in arbitrary, and in mis instance

anomalous, configurations. In other words, the ranking is cj. iticu.l 1\

related and indeed determines the accuracy and atr11ty or the

resulting percentage accumulations.

There are, however, a number of severe defects in the chart

of the district court. First, the court attempts to rank the various

departments of Pullman by job class range in an effort to show

comparative earnings potential. The use of JC range as the basis

of the ranking does not in any way indicate the actual dismibution.

or the ]ike]y distribution of employees in the JC's included xn

51/

the range.

In the chart, therefore, the Forge Department is rated as the

third most desirable department at the company. As shown elsewhere

in this brief, the median job class in the Forge Department is

JC 6; for blacks in the department the median is JC 2i There ai c

at least six departments which have both a higher median job class

52 / implicit in the use of range of JC as the has is for ranking

the departments is the assumption that employees within the depart

ment have a reasonable opportunity to rise to the coiling. This

assumption, however, is contrary to the facts, and employees

earnings potential is significantly affected by the average JC

customarily obtained in the department and the number of persons

within a JC.

40

and a larger work force.

The welding department, on the Court's chart, ranks as No. 16

53/

on the scale of 25 departments. Yet, with two exceptions- the

welding department ha.s a higher median job class than all the depart

ments listed above it, and is the largest department at the

54/

company.

Moreover, the substitution of JC range for average wage or

median job class of blacks and whites obscures the critical fact

that in 1965 blacks were essentially confined to less desirable

departments and the lower paying job classes while whites enjoyed

the benefits of the more renumcrative departments and higher job55/

c1ass occuput ions„

Second, the Court arbitrarily excludes some job classes to

determine the highest job class in the department and includes

others. In footnote 27 of its opinion, the Court explained that

since the highest indicated job class in the welding department

(JC 14) applied to an occupation to which less than one percent

of the department's employees were assigned, it would be disregarded.

However, in other departments where the highest rated occupation

was filled by less than one percent of the department's employees,

_52/

52/ see Median JC. chart, infra at 44.

53/ The maintenance department has a median JC 16, and

inspection has a median jc 12.

54/ Because of the size of the welding department, its place in

the ranking is critical.

55/ Compare, Petty;ay v. American Cast_Iron and Pipe Co., 494 P.2d

211, 230 (5th Cii.. 1.974 ), see chart E.

41

Thisthe Court included such job classes in its chart,

arbitrary exclusion of some job class boundaries and inclusion of

others inappropriately alters the ranking of the departments.

Third, it should be noted that the Court's chart improperly

omitted three highly paid all-White departments,- Die and Tool IAM,

57/Maintenance IAM, and Boiler House.

Fourth, despite the fact that a number of departments include

exactly the same range of JC's, the Court's chart assigns a different

ranking to departments having the same range. For instance,

56/ For example, the range of job classes in the Wood Mill is

shown as JC 1-11. The occupations worked in that department for

the years 1962-1965 were ail in JC 1 - JC 9; only in the period

1966-1969 was a JC 11 occupation worked — and then by a single

white employee. Since that time, the occupation has not been

worked. in Wood Erection, the only JC 11 occupation has been

manned by a single white employee for ten of the past eleven years.

(PX 11-20) In the Paint Department, containing some 272 employees,

only five (all of whom were whites) occupied JC 3.1 jobs. (PX 11-20)

Less than one percent of all the employees in the Steel construction

Department worked in a PC .11 occupation in the pre-1966 period.

( PX 1-10 ) Yet the Court listed all from departments as having

JC ranges up to 11. (R.I[16] p. 10)

57/ The company has total responsibility for assigning employees

to all departments, including the IAM departments; there is no

reason to exclude them from the ranking. (R. I [7] [13]]

42

(

s. const., paint ST, s. erection, w. erection, w. mill are

ranked 11-15, respectively. Each of these five departments,

however, has the same range of JC's, i. e. , 1-11 58/ in no way

does this scheme account for the assignment of greater earnings

potential to steel construction (ranked #11) than to wood mill

(.ranked 15) . By definition this assignment of different weights

to departments having the same so-called earnings potential dis

torts the accuracy of the "ranking" immeasurably.

Fifth, the court, in contradiction with undisputed facts and

in contravention of plainly established law excluded the welding

and: maintenance CIO departments from Column III of the chart.

The basis for the exclusion - the court's finding that a high

proportion of the jobs in welding and maintenance require

special training - is in conflict with unchallenged evidence. The

evidence shows and the court finds, in another part of the opinion

59/

that " . . . due to job segregation, there were only white welders."

The evidence further shows, and the court finds that during the

pre-1965 era whites were not required to possess any formal

or specialized training in welding and acquired the welder

position with only on-the-job training at the company.60 / There

58/ This occurs in three additional instances. That is, welding

and wheel and.axle are "ranked" 16 and 17, respectively, yet both

contain the same range, 1-10. steel mice, and s. stores are "ranked

18 and 19, respectively, and each includes the range 2-9. Lumber

stores and raise. Stores are ranked 21 and 22, respectively, and too

have the same range of JC's.

59/ R. I [ 16] n. 16

60/ R. I [16] n. 16 -

- 43 -

is no evidence whatsoever in the record which even suggests

that employees in maintenance CIO were required to demonstrate

special training as a prerequisite for entry into the department

As a result of its erroneous perception of the reason for

blacks' exclusion from welding before 1965, the court excludes

welding, containing nearly half the employees at Pullman, from

Column III of the chart, and retains the mobile crane department;

with 5 employees, to present a "more realistic picture." 61/

Finally, the accumulation of percentages, using job class

.range as the basis for ranking, disregards the racial imbalance

within departments and the concentration of blacks in the lower

JC's of the range. 62/

61/ R. I [16] p. 12

62/ The chart below ranks the departments in column III of the

district court's chart according, to job class median, Departmen

having the same job class median are rankeci, in descending oi ch.r

according to size, maintenance CIO and welding are included whil

the mobile crane department is not.

Median Job Classes of "Mixed" Departments

As of June, 1965

Dept.

Maint. CIO

Welding

Paint & ST Railroad Steel Erectio)

Steel Constr.

Wheel & Axle

Forge

Misc. Stores

Wood Mill Punch R Shear

Wood Erection

PressLumber Stores Steel Stores

Job Class Median JC % Blacks Accum.AA

Median Blacks in Dept. B w

13 4 21.0 2.5 8.9

10 6 19.2 18.3 70.6

7 6 52.0 27.2 78.2

7 7 44.4 28.0 . 7 9.1

1 6 6 87.6 56.4 82.8

6 6 87.3 68.5 84.4

6 6 30.2 69.8 87.1

6 2 37.5 71.0 88.9

6 7 53.8 71.7 09.4

5 2 29.2 72.4 90.9

4 3 81.1 84.1 93.4

4 2 65.0 90.5 96.6

4 4 7 3.8 95.2 98.].

.3 3 41.7 95.7 98.7

2 2 81.8 100.1 99.6

PX 2, 12, 51 CDX 26244 SOURCE:

These statistical manipulations led the Court to the

astonishing conclusion that blacks held a favored position as

to departmental assignments in 1965. That patently erroneous

finding is the basis for the court's erroneous legal conclusion

that Pullman's departmental seniority system had no "lock-in"

ef feet*

The District. Court Mistaken] y Failed to Grant Plaintiffs Full

Relief by Denying Their Claims for Carry-Over Seniority and. Wage

Rate Retention.

Contrary to the view of the district court, Pullman's De

partmental seniority system unlawfully locks black employees into

inferior jobs and departments. The facts show, in actuality, the

lot of black workers at Pullman scarcely improved in the decade

following Title vil's enactment. In 1964, virtually all (90.04%)

of the blacks at Pullman were confined because of their race to

occupations in JC 8 or below. (PX 61) Only one black held a

position above JC 10 (PX 61) Less than a fifth (18.4%) of the

v.'hite employees occupied jobs in JC 8 or below; nearly three-

fourths (79.7%) were assigned, to occupations in JC 10 or above.

(PX 61) 63_/

By June, 1973 nearly three-fourths of all the black production

and maintenance workers were still confined to occupations in JC

8 or below. (PX 55) At the same time, only 15.8% of the white

workers were assigned to such occupations. While four-fifths

(80.7%) of the white occupations wore assigned to occupations

rated as JC 10 or higher, less than one-fifth (19.9%) of the

black workers were so assigned.. 6%

H Y A-ct^cTTIyhe pe~rcontage of whites in JC 10 (or its equivalent

or above is higher than indicated on PX 61, since most of the JAM

craft jobs are excluded from the exhibit.

64/ The Court, stating in fn. 31 that PX 55 showed "that 19.9% of

45

I 0

ijL'he lower court's suggestion thet blcicks earned, approximately

96. 8% of the average total for whites in 1973 falls to account,

for the fact that older black employees must work overtime to

equalise their income with whites. (CDX 351, p. 52) Defendants

evidence showed that blacks indeed obtained more overtime work

than white workers. (Tr. 3706, 3707; CDX 351, p. 63) To the

extent, therefore, that any study of comparative earnings of

black and white workers does not take into account the factor

. 6<y (Cont'd)

the whites held positions on the rosters above JC 10 as compared wit):

only 12 2% of the blacks," misquotes plaintiffs' exhibit 55. Plain

tiffs' Exhibit 55 derived from seniority rosters shows that as or

June 1973: