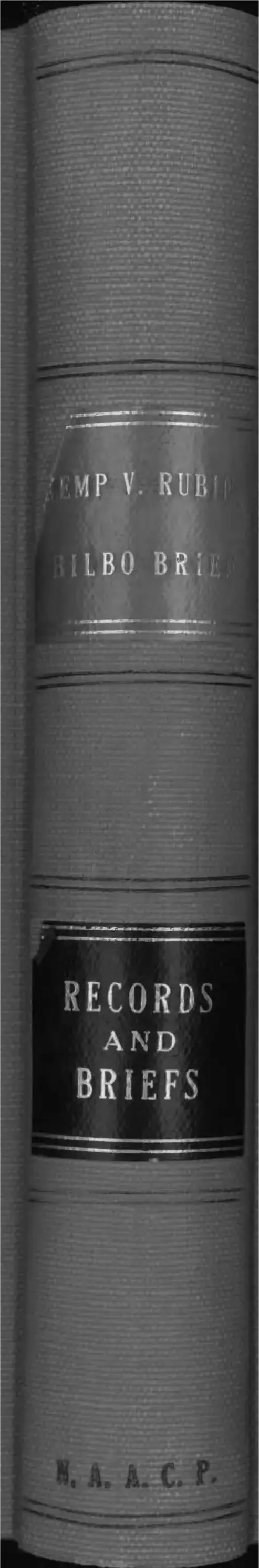

Kemp v. Rubin Records and Briefs

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1945 - January 1, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kemp v. Rubin Records and Briefs, 1945. 57e53553-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9a5020da-0e31-4dbb-b7b8-1c35d8601de1/kemp-v-rubin-records-and-briefs. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

RECORDS

AND

BRI E F S

t

^uprrmr dourt of tip i>tatr of 18m fork

Appellate Division— Second Department

Harold F. K emp, Sarah M. K emp, John H. Lutz and I rene

Lutz, on behalf of themselves and all others equally in

terested,

Plaintiffs-Respondents,

against

Sophie Rubin and Samuel R ichardson,

Defendants-Appellants.

R ECO R D ON A P P E A L

A ndrew D. W einberger,

Attorney for Defendant-Appellant

Samuel Richardson,

67 West 44th Street,

New York 18, N. Y.

Paul R. Silverstein,

Attorney for Defendant-Appellant

Sophie Rubin,

89-31 161st Street,

Jamaica, N. Y.

W ait, W ilson & Newton,

Attorneys for Plaintiff s-Respondents,

11 Park Place,

New York 7, N. Y.

Grosby Press, Inc., 30 Ferry St., N. Y . C.— BEekman— 3-2336-7-8

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement Under Rule 234 ............................. 1

Notice of Appeal of Defendant Samuel Rich

ardson ............................................................ 3

Notice of Appeal of Defendant Sophie Rubin 5

Summons .......................................................... 7

Amended Complaint......................................... 8

Exhibit A, Annexed to Com plaint........ 14

Exhibit B, Annexed to Com plaint........ 20

Answer of Defendant Sophie Rubin to

Amended Complaint ................................... 27

Answer of Defendant Samuel Richardson to

Amended Com plaint..................................... 35

Judgment ........................................................... 38

Case and Exceptions ....................................... 41

Defendant Richardson’s Motion to Dis

miss Complaint ..................................... 88

Defendant Rubin’s Motion to Dismiss

Complaint ............................................... 121

Defendant Rubin’s Motion to Dismiss

Complaint Renewed ............................. 180

Opinion by Mr. Justice Livingston .............. 184

Order Settling Case ............................. 191

Stipulation Waiving Certification ................ 193

Order Filing Record in Appellate Division .. 193

11

t

Plaintiffs’ W itnesses

page

Harold F. Kemp

Direct ........................................................ 42

Cross (by Mr. Weinberger) .................... 52

Cross (by Mr. Silverstein) ...................... 54

John H. Lutz

Direct ......................................................... 65

Cross (by Mr. Silverstein) ...................... 69

Defendant Rubin ’s W itnesses

Irving L. Schuh

Direct ........................................................... 128

Vera G. Jenkins

Direct .......................................................... 137

Beasley D. Kelly

Direct ......................................................... 140

Recalled

Direct ...........................................................

Helen Levy

Direct ......................................................... 147

Ferdinand W. Buermeyer

Direct ......................................................... 148

William E. Taube

Direct ...................................................... 152

Fred Williams

Direct ......................................................... 156

Andrew Reis

Direct ......................................................... 158

Cross ........................................................... 162

R edirect....................................................... 164

Ill

Plaintiffs’ E xhibits:*

Admitted

Page

1—Photograph of home of Harold F. Kemp,

one of the plaintiff-respondents .............. 44

2— A, 2-B, 2-C and 2-D. Photographs of the

two houses to the north of Harold F. Kemp

on the same side of the street and of the

remaining houses within the block between

112th Avenue and 114th Avenue in St.

Albans, New Y o r k ....................................... 45

3— Tax map of the City of New York showing

the location of the premises in issu e ........ 46

4—Agreement of restrictive covenant dated

January 10, 1939 signed by Harold F.

Kemp, Sarah M. Kemp and Sophie Rubin 46

5— Agreement of restrictive covenant dated

January 10,1939 affecting the side of 177th

Street wherein John H. Lutz and Irene

Lutz reside ................................................... 50

6— A, 6-B and 6-C. Photographs of houses

on side of 177th Street wherein John H.

Lutz and Irene Lutz reside ..................... 66

7— Photograph of 177th Street looking north

from 114th Avenue toward 112th Avenue,

St. Albans, New York ............................... 66

8— Sketch upon which certain lots are shaded

in red, representing those lots covered by

the agreements of restrictive covenant .. 68

* Omitted pursuant to Order Settling Case, herein

printed at pages 191-2.

IV

Defendant R u b in ’s E xh ibits :*

Admitted

Page

A For Identification— Certified copy of writ

ing dated July 26, 1943 recorded in Office

of the Register of Queens County, August

26, 1943 in Liber 4734 of Conveyances,

page 467 . . . •................................................. 132

B For Identification—Writing dated June 2,

1941, recorded January 10, 1942 in Office

of the Register of Queens County, January

10,1942 in Liber 4513 of Deeds, page 293 .. 132

C—Map of Addisleigh section of St. Albans

containing certain portions shaded in red

representing bouses occupied by colored

persons........................................................... 144

C.l—List with addresses of colored families

residing in Addisleigh section of St. Al

bans, New Y o r k ........................................... 144

D—List of colored residents in Addisleigh

area of St. Albans, New York with ad

dresses ............................................................ 171

* Omitted pursuant to Order Settling Case, herein

printed at pages 191-2.

(Unurt nf tfjr o f 2m h fo r k

Appellate Division—Second Department

1

------------------ 4------------------

H aeold F. K emp, Sarah M. K emp, John H. Lutz

and Irene Lutz, on behalf of themselves and

all others equally interested,

Plaintiff s-Respondents,

against

Sophie Rubin and Samuel Richardson,

Defendants-Appellants.

------------------ +-------------------

Statement Under Rule 234

This action was commenced on May 8,1946.

The summons and complaint were served on de

fendant Sophie Rubin on May 8,1946.

The answer of defendant Sophie Rubin was

served on June 4, 1946.

The first amended answer of defendant Sophie

Rubin was served on July 1, 1946.

The amended complaint was served on defend

ant Sophie Rubin on July 5,1946.

The amended answer of defendant Sophie Rubin

was served on July 24,1946.

There has been a change of parties in this action

in that the summons and complaint designated as

defendants the fictitious persons “ John Doe and

Jane Roe” . Thereafter, and on July 5, 1946

the amended complaint dropped the defendants

2

4 Statement Under Rule 234

“ John Doe and Jane Roe” and designated Sophie

Rubin as sole defendant.

On August 29th a motion was made by Samuel

Richardson pursuant to Civil Practice Act 193 sub

division 3, for leave to intervene as a party in in

terest, which motion was granted by order of Mr.

Justice Thomas C. Kadien on the 13th day of Sep

tember 1946.

The amended complaint was served upon de-

g fendant Samuel Richardson on the 5th day of

September, 1946.

The answer of defendant Samuel Richardson

was served on the 26th day of September, 1946.

6

3

Notice of Appeal of Defendant Samuel

Richardson

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE

OF NEW YORK

County of Queens

------------------- ♦--------------------

H arold F. K emp, Sarah M. K emp, John H. L utz

and Irene Lutz, on behalf of themselves and

all others equally interested, g

Plaintiffs,

against

Sophie Rubin and Samuel R ichardson,

Defendants.

------------------- ♦ -------------------

Sirs:

Please take notice that the defendant Samuel

Richardson hereby appeals to the Supreme Court,

Appellate Division, Second Department, from the

judgment of this Court in this action, entered in ̂

the office of the Clerk of the County of Queens on

March 1,1947 in favor of the plaintiffs and against

the defendants Samuel Richardson and Sophie

Rubin, permanently restraining and enjoining the

said Sophie Rubin until December 31, 1975 from

permitting the use or occupancy by, or selling,

conveying, leasing, renting or giving to Samuel

Richardson, a Negro, or to any person or persons

of the Negro race, blood or descent, the premises

112-03 177th Street, St. Albans, New York, and

permanently restraining and enjoining the said

Samuel Richardson until December 31, 1975 from

4

10 Notice of Appeal of Defendant Samuel

Richardson

using or occupying or buying, leasing, renting, or

taking a conveyance or gift from the defendant

Sophie Rubin or others of the premises 112-03

177th Street, St. Albans, N. Y. and appeals from

each and every part of said judgment as well as

from the whole thereof.

Dated, New York, March 25, 1947.

11 Yours, etc.,

A ndrew D. W einberger,

Attorney for Defendant Samuel

Richardson,

67 West 44th Street,

New York 18, N. Y.

W ait, W ilson & Newton, Esqs.,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs,

11 Park Place,

New York City.

Paul R. Silverstein, Esq.,

Attorney for Defendant Sophie Rubin,

89-31161st Street,

Jamaica, N. Y.

Paul L ivoti, Esq.,

Clerk of Queens County.

5

Notice of Appeal of Defendant, Sophie Rubin

SUPREME COURT

Queens County

13

H arold F. K emp, Sarah M. K emp, John H. L utz

and Irene Lutz, on behalf of themselves and

all others equally interested,

Plaintiffs,

against 4̂

Sophie Rubin and Samuel Richardson,

Defendants.

------------------- +-------------------

Sirs:

P lease take notice that the defendant, Sophie

Rubin, hereby appeals to the Supreme Court,

Appellate Division, Second Department, from

the judgment of this Court in this action, entered

in the office of the Clerk of the County of Queens

on March 1, 1947, in favor of the plaintiffs and 45

against the defendants, Sophie Rubin and Samuel

Richardson, permanently restraining and enjoin

ing the said Sophie Rubin, until December 31,

1975, from permitting the use or occupancy by, or

selling, conveying, leasing, renting or giving to

Samuel Richardson, a negro, or to any person or

persons of the negro race, blood or descent, the

premises 112-03 177th Street, St. Albans, New

York, and permanently restraining and enjoining

the said Samuel Richardson until December 31,

1975, from using or occupying or buying, leasing,

6

Notice of Appeal of Defendant, Sophie Rubin

renting, or taking a conveyance or gift from the

defendant Sophie Rubin, or others, of the prem

ises 112-03 177th Street, St. Albans, N. Y. and

appeals from each and every part of said judg

ment, as well as from the whole thereof.

Dated: Jamaica, New York, April 1, 1947.

Yours, etc.,

y . Paul R. Silverstein,

Attorney for Defendant,

Sophie Rubin,

Office & P. 0. Address,

89-31 161st Street,

Jamaica, New York.

To:

W ait, W ilson & Newton, Esqs.,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs,

11 Park Place, New York City.

A ndrew D. W einberger, Esq.,

2g Attorney for Defendant,

Samuel Richardson,

67 West 44th St., New York City.

Paul L ivoti, Esq.,

Clerk of Queens County.

7

Summons

19

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE

OF NEW YORK

County of Queens

+

H arold F. K emp, Sarah M. K emp, John H. L utz

and Irene L utz, on behalf of themselves and

all others equally interested,

Plaintiffs, 20

against

Sophie Rubin, John Doe and Jane Roe, the last

two named being fictitious, true names being

unknown, the person or persons intended being

in negotiation to violate the agreement for re

strictive covenant the subject of this action,

Defendants.

♦

Plaintiffs designate Queens County as the place

of trial. 21

To the above named Defendant:

You are hereby summoned to answer the com

plaint in this action, and to serve a copy of your

answer, or, if the complaint is not served with

this summons, to serve a notice of appearance, on

the Plaintiffs’ Attorney within twenty days after

the service of this summons, exclusive of the day

of service; and in case of your failure to appear,

or answer, judgment will be taken against you

8

2 2 Amended Complaint

by default, for the relief demanded in the com

plaint.

Dated, May 6th, 1946.

23

W ait, W ilson & Newton,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs,

Office and Post Office Address:

11 Park Place,

New York 7, N. Y.

Amended Complaint

SUPREME COURT

Queens County

------------------ 1-------------------

[SAME TITLE]

-------------------1-------------------

The plaintiffs by Wait, Wilson & Newton, their

attorneys, complaining of the defendants for their

amended complaint allege:

1. That on or about the 10th day of January,

1939, the plaintiffs and the defendant Sophie

Rubin and others being residents and owners of

lots in the section of St. Albans, Queens County,

New York, known as Addisleigh, executed in two

instruments, an agreement for a restrictive cove

nant of the lands known as Blocks 12631 and 12632

of Section 51, Land Map of Queens County, which

restrictive covenants were duly recorded in the

office of the Register of the County of Queens in

9

Liber 4146 at pages 394, and 399 of Conveyances,

on January 2, 1940, at 10:13 A. M., indexed under

section 51 in Blocks 12631 and 12632, which in

struments are annexed hereto and made a part

hereof as Exhibits A and B.

2. That the plaintiffs Harold F. Kemp and

Sarah M. Kemp are the owners in fee and the

occupants of the premises known as 112-59 177th

Street, St. Albans, New York, which premises

have a frontage of 60 feet on 177th Street, and 26

have a depth of 100 feet on either side, being

known as Lot 4 in Block 12631 of Section 51 on

the Land Map of the County of Queens.

3. That John Id. Lutz and Irene Lutz are the

owners in fee and the occupants of the premises

known as 112-20 177th Street, St. Albans, New

York, which premises have a frontage of 45 feet

on 177th Street and a depth of 100 feet on either

side, being known as Lot 46 in Block 12632 of

Section 51 on the Land Map of the County of

Queens. 9_

4. On information and belief that the defendant

Sophie Rubin is the owner in fee and one of the

occupants of premises known as 112-03 177th

Street, St. Albans, New York, which premises

have a frontage of 40 feet on 177th Street and a

depth of 100 feet on either side, being known as

Lot 28 in Block 12631 of Section 51 on the Land

Map of the County of Queens.

5. That the plaintiffs Harold F. Kemp, Sarah

M. Kemp, John H. Lutz and Irene Lutz and the

Amended Complaint *0

10

28

29

30

defendant Sophie Rubin, duly signed and acknowl

edged the agreement for the covenant aforesaid

in paragraph 1 of this complaint.

6. That the aforesaid agreement for restrictive

covenant provided as follows:

“ Whereas the said parties hereto desire,

for their mutual benefit as well as for the

best interests of the said community and

neighborhood, to improve and further the

interests of said community.

Now therefore, in consideration of the

premises and mutual promises and the sum

of One Dollar ($1.00) each to the other in

hand paid, and other valuable consideration,

the parties hereto do hereby create, impose

and establish, and do hereby mutually cove

nant, promise and agree each with the other

and for their respective heirs, successors and

assigns, that no part of the land now owned

by the parties hereto, a more detailed de

scription of said property being given after

the respective signatures hereto, shall ever

be used or occupied by, or sold, conveyed,

leased, rented, or given, to Negroes or any

person or persons of the Negro race or blood

or descent. This covenant shall run with

the land and bind the respective heirs, suc

cessors, and assigns of the parties hereto

until December 31st, 1975.”

Amended Complaint

7. On information and belief that the defend

ant Sophie Rubin has entered into negotiations

with persons of the Negro race for the sale of

11

the premises owned in fee by her and known as

112-03 177th Street, St. Albans, New York.

8. On information and belief that the defend

ant Sophie Rubin has made a contract of sale

with, and received a deposit from a person or

persons of the Negro race, for the sale of the

premises known as 112-03 177th Street, St. Albans,

New York. *

9. On information and belief that the defend- 32

ant Sophie Rubin intends to carry out the ne

gotiations for the sale of the premises known as

112-03 177th Street, St. Albans, New York, and

to carry out the sale of said premises to a per

son or persons of the Negro race.

10. That said sale of the said premises 112-03

177th Street, St. Albans, New York, would be in

violation of the agreement for restrictive cov

enant duly recorded and mentioned in paragraph

1 of this complaint, and which the defendant So

phie Rubin duly signed and is a party thereto. 00

33

11. That the premises owned by the plaintiffs

John H. Lutz, Irene Lutz, Harold F. Kemp and

Sarah M. Kemp are improved with private dwel

lings of a high class and of great value similar

to a large number of similar residences in the

said section known as Addisleigh.

12. That the houses of the plaintiffs Harold F.

Kemp, Sarah M. Kemp, John H. Lutz and Irene

Lutz are of large rental value and are desirable

residences, but that said rental values and said

desirability as residences, as well as their fee

Amended Complaint c ' ±

12

value depends wholly upon the exclusion from

the vicinity, and especially from the premises

owned and occupied by plaintiffs and defendant

Sohpie Rubin, of persons who are Negroes or

persons of the Negro race or blood or descent.

13. That the plaintiffs entered into the agree

ment for restrictive covenant believing that by

reason thereof the occupancy of all of the build

ings owned by them and the other parties to

35 the agreement for restrictive covenant, would

be restricted as provided for in said agreement.

14. That plaintiffs will suffer substantial dam

age if the conveyance or transfer intended by the

defendant Sophie Rubin is permitted to be com

pleted.

15. That plaintiffs have no adequate remedy

at law and would suffer great pecuniary loss and

will be substantially and irreparably injured and

damaged and will suffer great injuries which

will be difficult of ascertainment unless the in-

junction prayed for herein is granted.

W herefore, plaintiffs demand judgment that

the defendant Sophie Rubin be permanently, and

pending the hearing and determination of this

action, temporarily, restrained and enjoined from

permitting the use or occupancy by, selling, con

veying, leasing, renting or giving to, Negroes or

to any person or persons of the Negro race or

blood or descent until December 31st, 1975, the

said premises 112-03 177th Street, St. Albans,

New York, and for such other and further relief

04 Amended Complaint

13

to plaintiffs as to the Court may seem just and

Amended Complaint

proper.

W ait, W ilson & Newton,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs,

Office & P. 0. Address,

11 Park Place,

Borough of Manhattan,

New York City.

(Duly verified on July 3, 1946 by John H. and

Irene Lutz, Sarah M. Kemp and Harold F. Kemp 38

as plaintiffs.)

39

14

40

EXHIBIT A, ANNEXED TO AMENDED

COMPLAINT

Deed 4146 Page 399

A greement eor R estrictive Covenant

This indenture made this 10th day of January,

1939, by and between the undersigned, all being

residents of Queens County, New York, and own

ers of real estate situated therein, witnesseth

41 that;

Whereas the said parties hereto are owners of

real estate situated in Queens County, being in

the block bounded on the north by 112th Avenue,

on the east by 178th Street, on the south by 114th

Avenue, and on the west by 177th Street, and being

in Block No. 12631, Land Map of the County of

Queens, and

Whereas the said parties hereto desire, for

their mutual benefit as well as for the best inter

ests of the said community and neighborhood, to

improve and further the interests of said com-

42 munity.

Now therefore, in consideration of the premises

and mutual promises and the sum of One Dollar

($1.00) each to the other in hand paid, and other

valuable consideration, the parties hereto do

hereby create, impose and establish, and do hereby

mutually covenant, promises and agree each with

the other and for their respective heirs, succes

sors and assigns, (that no part of the land now

owned by the parties hereto, a more detailed

description of said property being given after

the respective signatures hereto, shall ever be

15

used or occupied by, or sold, conveyed, leased,

rented, or given, to Negroes or any person or

persons of the Negro race or blood or descent.

This covenant shall run with the land and bind

the respective heirs, successors, and assigns of

the parties hereto until December 31st, 1975.

It is understood that the holders of mortgages

affecting the premises owned by the undersigned

are omitted from this agreement, but this shall

not affect the validity of this agreement.

44

Name Address

Sophie Rubin 112-03 177 St

James Sovagl 112-35 177 St

Roger R. Grillon 112-11 177th St

Emily Nonni 112-23 177th St

Victor J. Jenkins 112-07 177th Street

Arthur Beck 112-27 177th St

George E. Baer 112-18 178th St.

Michelle G. Grillon 112-18 178th St.

Edward A. Canter 112-26 178th St.

Hattie W. Canter 112-26 178th St.

Harry C. Zimmer 112-22 178th St.

(illigible) 177-15 114th Avenue

Deed 4146 Page 400

Bessie A. Scott 112-44 178 St. St. Albans

W. S. Kaufmann 112-40 178 St., St. Albans

Harold F. Kemp 112-89 177th St., St. Albans

Sarah M. Kemp 112-59 177th St.

Arthur Levey 112-05 178th Place, St. Albans

Vera G. Jenkins 112-07 177th Street

Exhibit A, Annexed to Amended Complaint ^

I

16

4 6 Exhibit A, Annexed to Amended Complaint

Deed 4146 Page 401

State of New Y ork

'County of Queens

On the 25th day of September, one thousand

nine hundred and thirty-nine before me came

Sophie Rubin to me known to be the individual

described in, and who executed, the foregoing in

strument, and acknowledged that she executed

47 the same.

F rank J. Menig

Notary Public: Queens County

Reg. #3865, Clerks #3439

Term exp-3-30-40

State of New Y ork

County of Queens

On the 25th day of September, one thousand

nine hundred and thirty-nine before me came

48 James Savage to me known to be the individual

described in, and who executed, the foregoing in

strument, and acknoweldged that he executed the

same.

Frank J. Menig

Notary Public: Queens County

Reg. #3865, Clerks #3439

Term expires 3/30/40

17

State of New Y ork

'County of Queens

On the 28th day of September, one thousand

nine hundred and thirty-nine before me came

Harold F. Kemp and Sarah M. Kemp to me

known to be the individuals described in, and who

executed, the foregoing instrument, and acknowl

edged that they execute the same.

F rank J. Menig

Notary Public: Queens County

Reg. No. 3865, Clerk’s No. 3439

Term expires 3/30/40

State of New Y ork

C ounty of Queens

On the 21st day of October, one thousand nine

hundred and thirty-nine before me came Arthur

P. Beck the subscribing witness to the foregoing

instrument, with whom I am personally ac

quainted, who, being by me duly sworn, did depose 51

and say that he resides at 112-27 177th St., St.

Albans, in Queens County; that he knows Emily

Nonni to be the individual described in, and who

executed, the foregoing instrument; that he, said

subscribing witness, was present and saw Emily

Nonni execute the same; that he, said witness, at

the time subscribed his name as witness thereto.

Regina J. Schmidt

Notary Public: Queens County

Co. Clk’s #3671, Reg. #3452

Term exp. 3/30/1940

Exhibit A, Annexed to Amended Complaint

18

Exhibit A, Annexed to Amended Complaint

Deed 4146 Page 402

State of New Y ork

■County of Queens

On the 21st day of October, one thousand nine

hundred and thirty-nine before me came Roger R.

Grillon and Michelle Gr. G-rillon and Arthur Beck

to me known to be the individuals described in,

and who executed, the foregoing instrument, and

acknowledged that they executed the same.

Regina J. Schmidt

Notary Public: Queens County

Co. Clk No. 3671, Reg. No. 3453

Term expires 3/30/1940

State of New Y ork

County of Queens

On the 24th day of October, one thousand nine

hundred and thirty-nine before me came Victor

J. Jenkins and Vera 0. Jenkins to me known to be

the individuals described in, and who executed,

the foregoing instrument, and acknowledged that

they executed the same.

Regina J. Schmidt

Notary Public: Queens County

Co. Clk. No. 3671, Reg. No. 3452

Term expires 3/30/1940

J 9

7

RESTRICTIVE COVENANT

Premises: Addisleigh

The land affected by the within instrument lies

in Section 51 in Bloch 12631 on the Land Map of

the County of Queens

J. N.

R. & R. to:

Mary McKeon 56

Room 513

163-18 Jamaica Avenue

Jamaica, New York

Exhibit A, Annexed to Amended Complaint °

Recorded in the Office of the Register of the

County of Queens, in Liber No. 4146 Page 399 of

Conveyances on Jan. 2,1940 at 10:13 A. M. and in

dexed under Section 51 Block 12631 on the Land

Map of the County of Queens.

Bernard M. Patten

Register 57

20

EXHIBIT B, ANNEXED TO AMENDED

COMPLAINT

Deed 4146 Page 394

A greement F or Restrictive Covenant

This indenture made this, 10th day of January,

1939, by and between the undersigned, all being

residents of Queens County, New York, and own

ers of real estate situated therein, witnesseth

that;

Whereas the said parties hereto are owners of

real estate situated in Queens County, being in

the block bounded on the north by 112th Avenue,

on the east by 177th Street, on the south by 114th

Avenue, and on the west by 176th Street, and

being in Block No. 12632, Land Map of the County

of Queens, and

Whereas the said parties hereto desire, for their

mutual benefit as well as for the best interests of

the said community and neighborhood, to improve

and further the interests of said community.

Now therefore, in consideration of the premises

and mutual promises and the sum of One Dollar

($1.00) each to the other in hand paid, and other

valuable consideration, the parties hereto do

hereby create, impose and establish, and do hereby

mutually covenant, promise and agree each with

the other and for their respective heirs, succes

sors and assigns, that no part of the land now

owned by the parties hereto, a more detailed de

scription of said property being given after the

respective signatures hereto, shall ever be used

or occupied by, or sold, conveyed, leased, rented,

or given, to Negroes or any person or persons of

21

Exhibit B, Annexed to Amended Complaint 61

the Negro race or blood or descent. This cove

nant shall run with the land and bind the re

spective heirs, successors, and assigns of the

parties hereto until December 31st, 1975.

It is understood that the holders of mortgages

affecting the premises owned by the undersigned

are omitted from this agreement, but this shall

not affect the validity of this agreement.

Name Address

John H. Lutz 112-20 177 St.

Olga Ruggiero 112-50 177 Street

Victor Ruggiero 112-50 177 St.

Florence A. Renaud 112-24— 177th Street

Janette Hewitt 112-40 177th Street

112-40—177 Street

176-15— 114th St.

112-15—176 St.

112-19 176 St. Albans

112-16 177 St.

62

Ross I. Hewitt

Edith L. Rowe

Alfred S. W olf

George Strasser

Nunzio Mancuso

Irene Lutz 112-20 177 St. 63

W insome H olding Coup.

By Herman Kirschhaum, Treas.

(Seal)

Description

Corner formed by intersection

of southerly side of 112th Ave.

and westerly side of 177th St.,

being 144 feet on 177th St. and

100 feet deep on each side.

22

64 Exhibit B, Annexed to Amended Complaint

Deed 4146 Page 395

State of New Y ork

County of Queens

On the 29th day of February, 1939, before me

came H erman K irschbaum, to me known, who,

being by me duly sworn, did depose and say that

be resides at 88-23 162 St. Jamaica, Queens

County in N. Y .; that be is the Treasurer of Win

some Holding Corp., the corporation described

65 in, and which executed, the foregoing instrument;

that be knows the seal of said corporation; that

the seal affixed to said instrument is such cor

porate seal; that it was so affixed by order of the

Board of Directors of said corporation, and that

be signed bis name thereto by like order.

Charles Mikelberg

Charles Mikelberg

Notary Public, Kings Co.

Kings Co. Clks. No. 164, Reg. No. 266

N. Y. Co. Clks. No. 516, Reg. No. 0M348

(36 Queens Co. Clk’s No. 280, Reg. No. 1757

Bronx Co. Clks. No. 36, Reg. No. 138M40

Nassau Co. Clk’s No. 21M40

Cert, filed in Westchester Co.

Commission Expires March 30, 1940

23

Exhibit B, Annexed to Amended Complaint

Deed 4146 Page 396

State of New Y ork

County of Queens

oo • o o . .

On the 21st day of October, one thousand nine

hundred and thirty-nine before me came V ictor

Ruggiero and Olga Ruggiero to me known to be

the individuals described in, and who executed,

the foregoing instrument, and acknowledged that

they executed the same.

Regina J. Schmidt

Notary Public : Queens County

Co Clk No 3671

Reg. No. 3452

Term expires 3/30/40

68

State of New Y ork

County of Queens jss. :

On the 21st day of October, one thousand nine

hundred and thirty-nine before me came John H.

L utz and I rene L utz to me known to be the in

dividuals described in, and who executed, the

foregoing instrument, and acknowledged that they

executed the same.

Regina J. Schmidt

Notary Public : Queens County

Co Clk No 3671

Reg. No. 3452

Term expires 3/30/40

69

24

State of New Y ork

County of Queens

On the 21st day of October, one thousand nine

hundred and thirty-nine before me came Janette

H ewitt and Ross I. H ewitt to me known to be the

individuals described in, and who executed, the

foregoing instrument, and acknowledged that they

executed the same.

Regina J. Schmidt

72 Notary Public : Queens County

Co Clk No 3671

Reg. No. 3452

Term expires 3/30/40

^ Exhibit B, Annexed to Amended Complaint

State of New Y ork

County of Queens

On the 21st day of October, one thousand nine

hundred and thirty-nine before me came John

H. L utz, the subscribing witness to the foregoing

instrument, with whom I am personally ac-

72 quainted, who, being by me duly sworn, did depose

and say that he resides at 112-20 177th Street,

St. Albans, in Queens County; that he knows

Nunzio Mancuso to be the individual described in,

and who executed, the foregoing instrument; that

he, said subscribing witness, was present and saw

Nunzio Mancuso execute the same; that he, said

witness, at the time subscribed his name as wit

ness thereto.

Regina J. Schmidt

Notary Public : Queens County

Co Clk No 3671

Reg. No. 3452

Term expires 3/30/40

25

Deed 4146 Page 397

Exhibit B, Annexed to Amended Complaint

State of New Y ork

'County of Queens

On the 21st day of October, one thousand nine

hundred and thirty-nine before me came F lor

ence A. Renaud to me known to be the individual

described in, and who executed, the foregoing in

strument, and acknowledged that she executed the

same.

Regina J. Schmidt

Notary Public : Queens County

Co Clk No 3671

Reg. No. 3452

Term expires 3/30/40

i O

26

Exhibit B, Annexed to Amended Complaint

Deed 4146 Page 398

6

RESTRICTIVE COVENANT

Premises: Addisleigh

77

The land affected by the within instrument lies

in Section 51 in Bloch 12632 on the Land Map of

the County of Queens

J. N.

R & R to :

Mary McKeon

Room 513

163-18 Jamaica Avenue

Jamaica, New York

78

Recorded in the Office of the Register of the

County of Queens, in Liber No. 4146 Page 394 of

Conveyances on Jan. 2, 1940 at 10:13 A. M., and

indexed under Section 51 Block 12632 on the Land

Map of the County of Queens.

Bernard M. Patten

Register

27

Answer of Defendant Sophie Rubin, to

Amended Complaint

SUPREME COURT

Queens County

79

------------♦------------

[SAME TITLE]

------------ *------------

The defendant, Sophie Rubin, by Paul R. Silver-

stein, her attorney, answering the amended com- gO

plaint, alleges:

First: Denies each and every allegation con

tained in paragraphs of the complaint numbered

; > 9 i < g ? > <6 10” , “ 11” , “ 12” , “ 13’ \14” , and

‘15*

Second: Denies each and every allegation con

tained in paragraph numbered “ 1” of the com

plaint, except that the defendant admits that said

defendant and the plaintiffs, Harold F. Kemp and

Sarah M. Kemp, his wife, are two of the parties

who were signatories to the certain agreement gp

with respect to the land known as Block #12631,

Section #51, on the Land Map of Queens County.

As AND FOE A FIRST DEFENSE, DEFENDANT

FURTHER ALLEGES:

Third: Upon information and belief, that the

block in which the defendant resides is one of

twenty-nine blocks, more or less, which comprise

the section known as Addisleigh Park, County of

Queens, City and State of New York.

Fourth: Upon information and belief, that

covenants and restrictions similar in form to Ex-

hibit A annexed to the complaint, to which this

defendant is a signatory, were prepared for all of

the land blocks in Addisleigh Park under a gen

eral plan and scheme, with the intent and purpose

that they were to be executed by a substantial

percentage of the respective owners in each of

said blocks intended to be effected thereby and

that the same were not to become effective or re

corded until executed by a substantial percentage

of the land owners as aforesaid.

F ifth : Upon information and belief, that it was

further intended under said general plan and

scheme that covenants similar in form to Exhibit

A annexed to the complaint affecting the remain

ing blocks in the said Addisleigh Park section

were to be recorded concurrently with the covenant

referred to as Exhibit A.

Sixth: Upon information and belief, that the

general plan and scheme failed because a sub

stantial percentage of the respective land owners

failed and/or refused to execute the covenants

affecting the blocks in which they owned real prop

erty.

Seventh: Upon information and belief, that

the only covenants similar in form to Exhibit A

annexed to the complaint ever recorded were

those affecting blocks 12631 and 12632 of the Land

Map of the County of Queens.

Eighth: Upon information and belief, the

aforesaid recordation was violative of the general

plan and scheme.

Ninth: Upon information and belief, that by

reason of all the foregoing the said covenants and

Answer of Defendant Sophie Rubin

29

restrictions referred to in the complaint as Ex

hibit A and B never became of any force and

effect and are invalid and unenforceable.

As AND FOR A SECOND DEFENSE, DEFENDANT

FURTHER ALLEGES:

Tenth: At all the times hereinafter mentioned,

the defendant was and still is the owner of prem

ises known as and by the street number 112-03

177th Street, St. Albans, New York, which prem- gg

ises have a frontage of 40 feet on 177th Street and

a depth of 100 feet on either side and lies in Block

12631, Section 51 on the Land Map of the County

of Queens.

Eleventh: On or about the 10th day of Janu

ary, 1939, the defendant herein, the plaintiffs,

Harold F. Kemp and Sarah M. Kemp, and others,

who ŵ ere then residents and owners of one family

houses on lots in the section of St. Albans, Queens

County, New York, known as Addisleigh Park,

situate in Block 12631, Section 51, on Land Map

of the County of Queens, executed a certain agree- 87

ment with respect to the property owned by them,

which agreement was recorded in the Office of the

Register of the County of Queens in Liber 4146 of

conveyances, page 399 on January 2, 1940, a

photostatic copy of which agreement is annexed

to the complaint and referred to in paragraph

“ 1” thereof as Exhibit A, and hereby incorpo

rated by reference with the same force and effect

as though the same were set forth in full and at

length.

Twelfth: Upon information and belief, Roger

R. Grillon and Michelle G. Grillon, his wife, two

Answer of Defendant Sophie Rubin

30

of the signatories to the agreement referred to in

paragraph “ Eleventh” hereof, conveyed premises

known as 112-11 177th Street, St. Albans, New

York, to Anna Williams, by deed dated October

6, 1942, recorded in the Office of the Register of

Queens County, on October 8, 1942, in Liber 4263

of conveyances, page 498.

Thirteenth: Upon information and belief, that

“ John” Williams, first name “ John” being ficti

tious, the true first name unknown to defendant,

is the husband of Anna Williams, the grantee men

tioned and described in the deed of conveyance re

ferred to in paragraph “ Twelfth” hereof, and

that the said “ John” Williams is a person of the

Negro race.

Fourteenth: That the said Anna Williams and

the said “ John” Williams, and their children,

ever since the 6th day of October, 1942, have

openly and notoriously continuously been in pos

session and occupation of premises 112-11 177th

Street, St. Albans, New York, to the knowledge of

gQ the plaintiffs herein and of the other signatories

to the agreement hereinbefore referred to as Ex

hibit A.

Fifteenth: Upon information and belief, no

action or proceeding has ever been instituted in

any Court of this State or of the United States to

enjoin the use and occupancy by the Williams fam

ily of the said premises 112-11 177th Street, St.

Albans, New York, by the plaintiffs or any of the

signatories, or their heirs, successors or assigns.

Sixteenth: By reason of all of the foregoing,

plaintiffs have waived all benefits, rights and priv-

° ° Answer of Defendant Sophie Rubin

31

ileges under the aforesaid agreement hereinbefore

referred to as Exhibit A.

As AND FOR A THIRD DEFENSE DEFENDANT

FURTHER ALLEGES:

Seventeenth: Defendant repeats each and

every allegation set forth in paragraphs “ Tenth”

to “ Fifteenth” , both inclusive, herein, as though

herein fully set forth.

Eighteenth: By reason of the foregoing, plain- 92

tiffs are guilty of such laches as should in equity

bar the plaintiffs from maintaining this action.

As AND FOR A FOURTH DEFENSE DEFENDANT

FURTHER ALLEGES :

Nineteenth: Defendant repeats each and every

allegation set forth in paragraphs “ Tenth” to

“ Fourteenth” both inclusive, herein, as though

herein fully set forth.

Twentieth: Upon information and belief, that

in addition to the premises occupied by the W il

liams family as aforesaid, three other houses in

the same block in which the plaintiffs, Harold F.

Kemp and Sarah M. Kemp, and this defendant

reside, are owned and/or occupied by persons of

the Negro race.

Twenty first: Upon information and belief,

that such ownership and/or occupancy as alleged

in paragraph “ Twentieth” hereof occurred sub

sequent to the date of the execution of the agree

ment hereinbefore referred to as Exhibit A.

Answer of Defendant Sophie Rubin

32

Twenty second: Upon information and belief,

that since the execution of the agreement herein

before referred to as Exhibit A, approximately

sixty residences in the Addisleigh Park section of

St. Albans are owned, rented and/or occupied by

persons of the Negro race.

Twenty third: That the general condition now

prevailing in the Addisleigh Park section of St.

Albans and in the block in which this defendant

resides, have become so altered that the terms and

9° conditions of the agreement heerinbefore referred

to as Exhibit A are no longer applicable to the

existing situation.

Twenty fourth: That by reason of the prem

ises, enforcement of the agreement hereinbefore

referred to as Exhibit A would be unjust, inequit

able and oppressive and cause great hardship with

little or no benefit to the parties to said agreement

or to the general neighborhood.

As AND FOE A FIFTH DEFENSE DEFENDANT

CjQ FUETHEE ALLEGES:

Twenty fifth: That the agreement referred to

in the amended complaint is void and invalid and

of no force or effect in that it constitutes an un

lawful restraint on alienation.

As AND FOE A SIXTH DEFENSE DEFENDANT

FUETHEE ALLEGES:

Twenty sixth: That the agreement referred to

in the complaint is void and invalid and of no force

and effect whatsoever in that its enforcement and

94 Answer of Defendant Sophie Rubin

33

the terms thereof are contrary to the provisions

and violative of the 14th Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States of America.

As AND FOE A SEVENTH DEFENSE DEFENDANT

FURTHER ALLEGES:

Twenty seventh: That the agreement referred

to in the complaint is void and invalid and of no

force or effect whatsoever in that its enforcement

and the terms thereof are contrary to the provi- gg

sions and violative of Article I, Section 11 of the

Constitution of the State of New York.

As AND FOR AN EIGHTH DEFENSE DEFENDANT

FURTHER ALLEGES:

Twenty eighth: That the agreement referred

to in the complaint and the enforcement thereof

by a Court of equity or by any Court of the State

of New York would result in segregation of

Negroes and other persons not of the white or

Caucasion race solely by reason of their race or

color which is contrary to the public policy of the

State of New York and contrary to the public pol

icy of the United States of America.

As AND FOR A NINTH DEFENSE DEFENDANT

FURTHER ALLEGES:

Twenty ninth: That the agreement referred to

in the complaint is void and invalid and of no

force or effect in that the terms thereof and the

enforcement thereof by any Court of the State

of New York are violative of the treaty obligations

of the United States of America under the Charter

Answer of Defendant Sophie Rubin y '

34

of the United States, Articles 55c and 56, which

treaty was made under the authority of the United

States.

Answer of Defendant Sophie Rubin

AS AND FOE A TENTH DEFENSE DEFENDANT

FURTHER ALLEGES:

Thirtieth: That the agreement referred to in

the complaint is void and invalid and of no force

or effect in that the terms thereof and the enforce-

ment thereof by any Court of the State of New

York are violative of the treaty obligations of the

United States of America under the Act of Cha-

pultepec of 1945, which treaty was made under the

authority of the United States.

W herefore, defendant demands judgment dis

missing the complaint, together with costs and

disbursements of this action.

102

Paul R. Silverstein,

Attorney for Defendant,

89-31 161st St., Jamaica, N. Y.

(Duly verified on 7/24/46 by Sophie Rubin as

defendant.)

35

Answer of Defendant Samuel Richardson, to

Amended Complaint

SUPREME COURT

Queens County

-------------------1-------------------

[SAME TITLE]

------------------- *-------------------

Defendant, Samuel Richardson, by his attor

ney, Andrew D. Weinberger, for his answer, al- 104

leges:

1. Denies each and every allegation contained

in paragraph 1 of the complaint, except admits

that an exhibit annexed to the complaint purports

to show a writing to which plaintiffs Harold and

Sarah Kemp and defendant Sophie Rubin are

signatories.

2. Denies knowledge or information sufficient

to form a belief as to the allegations contained in

paragraphs 2 and 3 of the complaint.

105

3. Denies each and every allegation contained

in paragraph 5 of the complaint except admits

that plaintiffs Kemp, defendant Rubin and others

not parties to this action signed a writing which

is shown in Exhibit 1 and that plaintiffs Lutz and

others not parties to this action signed a writing

which is shown in Exhibit 2.

4. Denies each and every allegation contained

in paragraph 6 of the complaint except the ex

ecution of the two exhibits annexed to the com

plaint as elsewhere herein admitted.

36

106 Answer of Defendant Samuel Richardson

5. Denies each and every allegation contained

in paragraph 10 of the complaint.

6. Denies each and every allegation contained

in paragraph 11 of the complaint except admits

that the premises referred to are improved with

private dwellings.

7. Denies each and every allegation contained

in paragraph 12 of the complaint.

107 8. Denies knowledge or information sufficient

to form a belief as to any of the allegations con

tained in paragraph 13 of the complaint.

9. Denies each and every allegation contained

in paragraph 14 of the complaint.

10. Denies each and every allegation contained

in paragraph 15 of the complaint.

As A FIRST SEPARATE AND COMPLETE DEFENSE

TO THIS ACTION

103 n . The covenant sued on herein cannot be

judicially enforced by reason of the prohibitions

contained in the 14th Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States and the laws enacted

thereunder.

As A SECOND SEPARATE AND COMPLETE DEFENSE

TO THIS ACTION

12. The enforcement of the covenant sued on

herein is prohibited by existing treaties entered

into between the United States and other nations

and which constitute the supreme law of the land.

37

As A THIRD SEPARATE AND COMPLETE DEFENSE

TO THIS ACTION

13. The covenant sued on herein is void and

may not be judicially enforced by reason of the

public policy of the United States and the State

of New York.

As A FOURTH SEPARATE AND COMPLETE DEFENSE

TO THIS ACTION

110

14. The covenant sued on herein cannot be

judicially enforced by reason of the prohibitions

contained in Article 1, Section 11 of the Con

stitution of the State of New York.

As A FIFTH SEPARATE AND COMPLETE DEFENSE

TO THIS ACTION

15. The covenant sued on herein is void as con

stituting an unlawful restraint on alienation of

real property.

I l l

W herefore, defendant Samuel Richardson de

mands judgment dismissing the complaint in this

action.

A ndrew D. W einberger,

Attorney for Defendant Samuel

Richardson,

67 West 44th Street,

New York 18, N. Y.

(Duly verified on September 24,1946 by Samuel

Richardson as defendant.)

Answer of Defendant Samuel Richardson

38

112

Judgment

At a Special Term, Part I of the Su

preme Court of the State of New

York, held in and for the County of

Queens, at the Queens County Gen

eral Court House, 88-11 Sutphin

Boulevard, Jamaica, Borough of

Queens, City and State of New York

on the 27th day of February, 1947.

P r e s e n t :

113

H on. Jacob H. L ivingston,

Justice.

--------------------♦ -------------------

[SAME TITLE]

------------------ i — — —— — •

The issues in this action having come on for

trial before Mr. Justice Jacob H. Livingston at

Special Term, Part I of this Court on the 6th, 7th

and 13th days of November, 1946 and this action

having been fully tried upon the issues presented

by the amended complaint and the amended an

i l ^ swer of defendant Sophie Rubin and the answer

of defendant Samuel Richardson, and the plain

tiffs having appeared herein by Wait, Wilson &

Newton, Esqs., their attorneys, Frederick W. New

ton, Esq. and William F. Cambell, Jr., Esq. of

counsel and the defendants having appeared as

follows: Sophie Rubin, by Paul Silverstein, Esq.

her attorney and Irving L. Schuh, of counsel,

Samuel Richardson by Andrew D. Weinberger,

Esq. his attorney and Vertner W. Tandy, Jr.,

Esq. of counsel and the following as amici curiae:

Will Maslow and Leo Pfeffer, Esq., on behalf of

39

the American-Jewish Congress and the American

Civil Liberties Union; Marion Wynn Perry, Esq.,

on behalf of the National Lawyers Guild; Witt &

Cammer, Esqs., by Mortimer B. Wolf, Esq. of

counsel, on behalf of New York State Industrial

Union Council and the Greater New York In

dustrial Union Council, C. I. 0., Charles Abrams,

Esq., attorney on behalf of City-wide Citizens

Committee of Harlem; William Kincaid Newman,

Esq., attorney on behalf of Social Action Com

mittee of the New York City Congregational 116

Church Association, Inc.; Robert L. Carter, Esq.,

attorney on behalf of Methodist Federation for

Social Service, and after hearing the proofs and

allegations of the plaintiffs and the defendants,

and due deliberation having been had thereon and

the Court having rendered its decision made and

filed on the 11th day of February, 1947.

Now on motion of Wait, Wilson & Newton, at

torneys for the plaintiffs Harold F. Kemp, Sarah

M. Kemp, John H. Lutz and Irene Lutz, it is

Ordered, adjudged and decreed that the de-

fendant Sophie Rubin be and she hereby is per

manently restrained and enjoined until December

31, 1975 from permitting the use or occupancy

by, or selling, conveying, leasing, renting or giv

ing to Samuel Richardson, a negro, or to any

person or persons of the Negro race, blood or

descent the premises 112-03 177th Street, St. Al

bans, New York, and it is further

Ordered, adjudged and decreed that the defend

ant Samuel Richardson be and he hereby is per

manently restrained and enjoined until December

Judgment 1 1 0

40

118 Judgment

31, 1975 from using or occupying or buying, leas

ing, renting, or taking a conveyance or gift from

the defendant Sophie Rubin or others of the

premises 112-03 177th Street, St. Albans, New

York, and it is further

Ordered, adjudged and decreed that the under

taking, on injunction pendente lite, as provided

by order of this Court dated July 9, 1946, given

on behalf of the plaintiff by The National Surety

119 Corporation, dated July 2, 1946 and approved by

this Court on the 9th day of July, 1946 in the

sum of Three thousand five hundred ($3,500.00)

Dollars is hereby cancelled and annulled and The

National Surety Corporation thereon is hereby

discharged from all liability upon such under

taking and it is further

Ordered, adjudged and decreed that the Clerk

of this Court is directed to enter judgment ac

cordingly.

Granted: February 28, 1947

P aul L ivoti,

Clerk.

Judgment entered March 1st, 1947 at 9 :10 A. M.

Enter,

120 Jacob H. L ivingston,

J. s. c.

(Seal) P aul L ivoti,

Clerk.

4 1

Case and Exceptions

SUPREME COURT

Queens County

Special Term— Part I

--------------------+-------------------

[SAME TITLE]

------------------- +-------------------

Jamaica, N. Y., November 6, 1946. 122

B e f o r e :

121

H on. Jacob H. L ivingston,

Justice

Appearances:

Wait, Wilson & Newton, Esqs.,

Attorneys for the plaintiffs,

By Frederick W. Newton, Esq. and

William F. Campbell, Jr., Esq.

Paul Silverstein, Esq., and

Irving L. Schuh, Esq.,

For the Defendant Rubin.

Andrew D. Weinberger, Esq., and

Vertner W. Tandy, Jr.,

For the Defendant Richardson.

American Jewish Congress and the American

Civil Liberties Union as amici curiae,

by Leo Pfeffer, Esq.

National Lawyers Guild as amicus curiae,

by Marion Wynn Perry, Esq.

42

New York State Industrial Union Council and

the Greater New York Industrial Union Coun

cil, C. I. 0. as amici curiae,

by Witt & Cammer, Esqs., by Mortimer B.

Wolf, Esq., of counsel.

City Wide Citizens Committee On Harlem as

amicus curiae,

by Charles Abrams, Esq.

Social Action Committee of the New York City

Congregational Church Association, as amicus

curiae,

by William Kincaid Newman, Esq.

Methodist Federation for Social Service as

amicus curiae,

by Robert L. Carter, Esq.

(Briefs were submitted to the Court and ex

changed among counsel.)

Harold F. Kemp—For Plaintiffs—Direct

H akold F. K emp, residing at 112-59— 177th

Street, St. Albans, Long Island, New York, called

as a witness on behalf of the plaintiffs, being first

duly sworn, testified as follows:

Direct examination by Mr. Newton-.

Q. Mr. Kemp, you are the owner of the prop

erty, 112-59—117th Street, are you? A. With my

wife.

Q. You and your wife------

Mr. Weinberger: If your Honor please, I

suggest that we may be able to save some of

43

the Court’s time by stipulating as to a few

of the pro forma facts.

Mr. Newton: I am not going to take more

than five minutes.

Mr. Weinberger: There are a number of

things that counsel may not be able to prove,

that we are ready to stipulate. We want to

get down to the fundamentals of law here.

Mr. Newton: All right, go ahead.

Mr. Weinberger: I offer to stipulate, on

the assumption that all of these items are 128

stipulated to pro and con, that the plaintiffs

Kemp own 112-59—177th Street, St. Albans;

that the plaintiffs Lutz own 112-20—177th

Street; that the covenants annexed to the

complaint were signed as indicated and re

corded ; that the plaintiffs are not negroes nor

of the negro race, blood, or descent; that the

defendant Richardson is a negro and a citizen

of the United States and of New York State;

and that the defendant Richardson owns the

vacant lot of land 40 by 100 feet abutting on

the rear of 112-03— 177th Street, which is the [29

property in suit here.

Mr. Newton: I will accept those conces

sions. That will save time. Thank you.

Are those concessions also made by the

defendant Rubin?

Mr. Silver stein: Yes, they are so made.

By Mr. Newton:

Q. Now, Mr. Kemp, how long have you oc

cupied those premises? A. About 22 years.

Q. As a private home? A. As a private home.

Q. Your property there, as I understand it, is

Harold F. Kemp—For Plaintiffs—Direct 1

44

about 60 by 120 feet, is that right? A. No, 100 by

120.

Mr. Weinberger: That is objected to. I

move to strike out the answer. The question

contains the word “ about” . The complaint

alleges that your property is 60 by 100 feet.

Counsel here does not ask the question, but

testifies that it is 100 by 120.

The Court: No; be said 60 by 120, and the

witness corrected him to 100 by 120.

131 The Witness: That’s right.

By Mr. Newton:

Q. Mr. Kemp, those lots on that street are

actually 60 feet wide, is that right? A. That is

correct.

Q. By 100 feet deep? A. Correct.

Q. Your property includes two lots, is that

right? A. That’s right.

Q. I show you a photograph and ask you if

that is a photograph of your home at that loca

tion. A. Yes, sir.

132 Mr. Newton: I offer the photograph in evi

dence, if the Court please.

Mr. Weinberger: No objection.

(Received in evidence and marked Plain

tiffs’ Exhibit 1.)

Q. Now, adjoining your property to the north

there is a vacant lot, is that right? A. Yes, sir.

The Court: May I ask a question? Would

the north be to the right of the picture, Plain

tiffs ’ Exhibit 1, or to the left?

Harold F. Kemp—For Plaintiffs—Direct

45

The Witness: To the left as you are look

ing at it.

Q. Then there is a house, I believe, that is

owned by a person by the name of Hemachandra?

A. Yes, sir, I believe so.

Q. I ask you if these are photographs of the

two houses to the north of you on your side of the

street. A. Yes, sir.

Q. I show you additional photographs and ask

you if those are the remaining houses on your side 134

of that street within that block between 112th

Avenue and 114th Avenue. A. I believe they are.

Mr. Newton: I offer them in evidence.

Mr. Weinberger: There is no objection,

your Honor, except to the photograph of 112-

15—177th Street, which is marked Budelman,

indicating that it is one house owned by

Budelman, when the fact is, I believe, that it

is a photograph of two houses taken at such

an angle that a tree obscures the division line

between the two. If that is noted on the rec

ord I have no objection. 135

The Court: Would it be very important to

the case?

Mr. Weinberger: No, I don’t think it will

be, but I do think that the plaintiffs are not

making an attempt to capitalize it.

Mr. Newton: I certainly consent that coun

sel’s statement be noted on the record, and

that it is correct.

(Received in evidence and marked Plain

tiffs’ Exhibits 2-A, 2-B, 2-C, and 2-D.)

Harold F. Kemp— For Plaintiffs—Direct

46

Harold F. Kemp—For Plaintiffs—Direct

By Mr. Newton:

Q. Those houses, so far as you know, Mr. Kemp,

are all occupied as single-family homes, is that

right ? A. As far as I know, yes.

Mr. Newton: If the Court please, I offer

in evidence a part of the tax map of the City

of New York. It is not for proof of any

boundary lines; it is merely to show the loca

tion of the premises that we are considering

237 and for no other purpose.

(Received in evidence and marked Plain

tiffs’ Exhibit 3.)

Mr. Newton: I offer in evidence agreement

for restrictive covenant dated January 10,

1939. That is the agreement referred to in

the stipulation of counsel. It is signed by the

plaintiffs Harold F. Kemp, Sarah M. Kemp,

and by the defendant Sophie Rubin, so I will

not have to prove the signatures.

(Received in evidence and marked Plain-

133 tiffs’ Exhibit 4.)

Mr. Newton: May it appear in the record

that the restrictive covenant, Exhibit 4, was

recorded in the Queens County Register’s

Office on January 2, 1940?

Mr. Weinberger: That is right.

By Mr. Newton:

Q. Mr. Kemp, at the time that you signed this

restrictive covenant, Exhibit 4, was anything said

about the other side of the street in that same

block that you live on ?

47

Mr. Weinberger: That is objected to.

Mr. Silverstein: The same objection.

A. I haven’t seen that covenant as yet.

The Court: Just a minute. When there

is an objection, do not answer.

Objection sustained. Strike out any an

swer.

Q. Was there at that time, within your knowl

edge, circulated and signed a restrictive covenant 140

affecting the other side of that street and in that

same block that you live in?

Mr. Weinberger: That is objected to. If

such a document were signed, let it be pro

duced and offered.

The Court: Objection sustained. What is

the basis of your complaint? Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit 4, or Exhibit 4 and another restrictive

covenant?

Mr. Newton: Both.

The Court: You allege in your complaint

another restrictive covenant. 141

Mr. Newton: I want to show—I will be

perfectly frank------

The Court: No; let us limit ourselves.

(Discussion off the record between the

Court and counsel.)

The Court: Now, I said that in your com

plaint you seek injunctive relief because of

the statements contained in this covenant,

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 4, and another one?

Mr. Newton: That is right.

The Court: Put the other one in evidence.

Harold F. Kemp—For Plaintiffs—Direct

Mr. Newton: I will do that. I offer in evi

dence, if the Court please, a restrictive cove

nant bearing the same date, January 10,

1939, affecting the other side of 177th Street,

in the same block between 112th Avenue and

114th Avenue, recorded in the Queens County

Register’s Office on the same date, January

2, 1940.

Mr. Silverstein: I object to the introduc

tion of that on the ground that a reading of

the instrument will indicate that there is no

privity whatsoever between either the defend

ant Rubin or any other parties whose names

are signatories to that agreement; that the

parties who are the signatories to the agree

ment now offered reside in another block;

that there is no reference whatsoever in the

agreement now in evidence as Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit 4 to the agreement now offered, or vice

versa; and that that agreement is not binding

upon this plaintiff.

Mr. Newton: In equity in an action to en

force one of these covenants where there are

two or more affected properties as part of a

common scheme or plan, the decisions uni

formly hold that they may all be shown, that

they may be proved together, and that the

relief may be granted without regard to priv

ity of estate or of contract.

If your Honor wishes to look at the cases,

they are on page 4 of my brief—Equitable

Life Insurance vs. Bregin, 148 N. Y. 661;

Saratoga State Waters Corporation vs.

Brach, 227 N. Y. 429.

The Court: Without going into that for

Harold F. Kemp— For Plaintiffs—Direct

49

the moment,—I am addressing myself to Mr.

Silver stein, who made the objection,—is it

one of your contentions that the change in

conditions makes this restrictive covenant in

operative?

Mr. Silverstein: That is one of the de

fenses.

The 'Court: Well, don’t you think that if it

is one of your defenses we ought to have the

picture of the entire neighborhood?

Mr. Silverstein: That is Avhat I want. I 146

don’t want the two blocks between the------

The Court: He is offering two blocks in

order to get a picture of the entire neighbor

hood. I don’t think that anybody would stop

you from offering a couple of more blocks,

and he would be establishing a precedent

which might enure to your benefit.

Mr. Silverstein: There is just one other

thought I want to point out. I claim by my

answer that that which seems to have valid

inception, these two instruments never had

any valid inception, because there was sup-

posed to be a common scheme and plan which

failed in its entirety.

The Court : Wouldn’t we get a better pic

ture of the situation if we had all covenants

in?

Mr. Silverstein: All covenants in, yes.

The Court: I think you ought to withdraw

your objection at this time and only urge the

striking out of this if there is substantial ob

jection made when you want to introduce one

and the ruling is against you.

Mr. Silverstein: May I reserve my right,

then?

Harold F. Kemp— For Plaintiffs—Direct 1'±0

50

148 Harold F. Kemp—For Plaintiffs—Direct

The Court: Yes.

Mr. Newton: I want to say at this time on

that subject, so that the Court may not mis

understand me, that I maintain that this

scheme which affected both sides of the street

is a unit, and that I have a right to show both

sides of the street, and that I have pleaded

both sides of the street. When it comes to

going up beyond that I say now to the Court

that I intend to object to it.

149 The Court: I won’t tell you how I will rule

then. The objection is withdrawn at this time

and counsel reserves the right to make such

objection later, and I give him that right.

(Received in evidence and marked Plain

tiffs’ Exhibit 5.)

By Mr. Newton:

Q. Mr. Kemp, did you know at the time that you

signed this restrictive covenant, Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit 4, that there was being circulated and signed

on the other side of the street an identical cove-

150 nant affecting the houses on that side of the street?

Mr. Weinberger: That is objected to as

calling for the operation of this witness’s

mind, either now or in 1939, and it is not

evidence.

The Court: I will let him answer it.

A. Yes, sir, I did.

Mr. Weinberger: Exception.

The Court: I want all of you to feel free

to take exceptions whenever you feel you need

them, without feeling that you are in anywise

bothering the Court. You are not.

51

Harold F. Kemp— For Plaintiffs— Direct 151

Q. How long have you owned and occupied that

house? Did I ask that question? A. You asked

that.

Mr. Newton: I ask for the production,

please, of the contract of sale made by the

defendant Sophie Rubin, to one Samuel Rich

ardson, of premises 112-03 177th Street.

Mr. Weinberger: A motion was made be

fore this Court, before we were in the case,

asking for the production and examination of

that contract. The motion was denied. The 152

pleadings admit that the defendant Richard

son signed a contract of purchase from the

defendant Rubin, and that pursuant to that

contract this real property has been sold by

Rubin to Richardson.

Mr. Newton: That is admitted now in the

record, is it?

Mr. Weinberger: It is admitted in the

pleadings.

The Court: Whether it is or not, do you

make that admission now?

Mr. Weinberger: Yes, sir.

The Court: So that we save looking up the °

paper at this moment. All right, that is all

you want, is it?

Mr. Newton: That is all I want. You may

examine.

The Court: This Richardson contract, or

the property covered by the proposed con

tract, is that on the same side of the street as

Kemp’s house, or on the other side of the

street ?

Mr. Weinberger: The same side as Mr.

Kemp’s house.

52

154 Harold F. Kemp—For Plaintiffs—Cross

The Court: In other words, Richardson’s

proposed grantor is a signatory------

Mr. Newton: To Exhibit 4, yes.

The Court: To the restricted covenant, is

that right?

Mr. Weinberger: Yes, sir, that is right.

Mr. Newton: You may examine.

Cross examination by Mr. W einberger:

Q. What is the assessed valuation of your

155 house, Mr. Kemp? A. I don’t know what it is.

Q. What did you pay in taxes on the house last

year? A. I can’t answer accurately, because I pay

so much a month. I believe it was around $250.

Q. Do you recall when I made a motion in this

court last August on behalf of the National Asso

ciation for the Advancement of Colored People,

pleading to come in amicus curiae? A. Do I recall

that? I was not here.

Q. Did counsel tell you that such a motion had

been filed with this court and served on him as

your attorney? A. About what?

156 Q- Did your attorney tell you that such a motion

had been filed? A. What kind of a motion?

Q. A motion for the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People to intervene

in this action as a friend of the court. A. No, sir.

Q. Did you know that such a motion was pend

ing? A. No, sir.

Q. It was widely reported in the newspapers,

but you didn’t see it there or hear of it from your

attorney, is that correct? A. I didn’t know it.

Q. Did you know that in the interval between

the time that those motion papers were served and

the return before this court on August 28th, in

53

your street in St. Albans and in the adjoining

streets notices had been put under the doors of

ten or twenty of the negro occupants and owners

of those houses warning them to get out of their

homes, and signed KKK?

Mr. Newton: I object, if the 'Court please.

The Court: Sustained. What has that to

do with this case?

Mr. Weinberger: I want to know what this

defendant had to do with it.

The Witness: I had nothing to do with it.

The Court: Wait a minute; don’t answer

it. I don’t see any connection. As I under

stand it, I am trying the case here in Special

Term to determine whether the plaintiff is

entitled to injunctive relief against Sophie

Rubin and Samuel Richardson. Is that right?

Mr. Weinberger: Yes, sir.

The Court: It is a legal proposition, as I

see it. They either are or they are not en

titled to it. I am sure you will concede that

I do not approve of any practices such as

those you have just mentioned, and I don’t 159

think any decent person does, but it has noth

ing to do with this case, and we must not con

fuse the issues.

Mr. Weinberger: Except that this case,

your Honor, is a more polite and more formal

version of just that sort of conduct.

The Court: No. I don’t think that this

Court would allow itself or lend itself to being

used as a branch or adjunct of the Klu Klux

Klan.

Mr. Weinberger: I don’t think this Court

will.

Harold F. Kemp—For Plaintiffs—Cross 10 ‘

54

160 Harold F. Kemp—For Plaintiffs—Cross

The Court: No, this Court won’t, nor

would any Judge of this court, I am sure.

Now, let us get down to the case.

Mr. Weinberger: That is all.

Cross examination by Mr. Silver stein:

Q. Mr. Kemp, how long have you owned your

home? A. About 22 years.

Q. What did you pay for it? A. About $21,000.

Q. Now, there is a party by the name of Hema-

161 chandra living next door to you? A. Hemachan-

dra.

Q. The family is colored, is it not? A. I believe

so.

Q. Do you know what your assessed valuation

of the property was in 1939? A. No, sir.

Q. Do you know how much you paid in taxes in

1939, real estate taxes? A. No, sir.

Q. How much are your real estate taxes today?

A. I said I thought they were about $250 a year.

I am not positive of it.

Q. Are you a member of the Addisleigh A. P. O.

252 Holding Corporation Association? A. Yes.

Q. How long have you been active in that or

ganization? A. I think it is around seven or eight

years.

Q. There is an area in St. Albans known as

Addisleigh, is that correct? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And that area of Addisleigh covers property

running along Linden Boulevard, on both sides of

it, up to the railroad, the Long Island Railroad,

near what is now the Naval Hospital, is that cor

rect? A. That is commonly what it is regarded as.

Q. Then it runs north along the railroad to

what would he known as 112th Avenue ? A. Addis-

leigli was not generally regarded to go down to

as far as 112th Avenue.

Q. Then, you tell me the area that is embraced

in Addisleigh, the Addisleigh section of St. A l

bans. A. Well, there is no way I can tell you

exactly how far north the Addisleigh section of

St. Albans was supposed to be.

The Court: What is your general impres

sion of the Addisleigh section?

The Witness: My general impression from

living there a number of years— there was a

woods there, there was a closed street, and

that street is now opened up and there is no

street running that way now that would close

—between 114th Avenue, or Murdoch Avenue

now, and 112th Avenue. The Addisleigh sec

tion as it was regarded before, that ran from

114th Avenue to this woods which is now

opened up.

The Court: That was your impression?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

By Mr. Silver stein:

Q. And your house is north of 114th Avenue, is

that correct? A. That is correct.

Q. Then, the property south of 112th Avenue is

in the Addisleigh section of St. Albans, is that

right? A. Not all of it, what I would consider the

Addisleigh section of St. Albans.

Q. Is Mr. Eubin’s house in the Addisleigh sec

tion of St. Albans? A. I would regard it in the

Addisleigh section.