School Board of Brevard County, Florida v. Weaver Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. School Board of Brevard County, Florida v. Weaver Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1972. 13c43357-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9a52f0bf-97bd-4e28-a301-81305d85c093/school-board-of-brevard-county-florida-v-weaver-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I k the

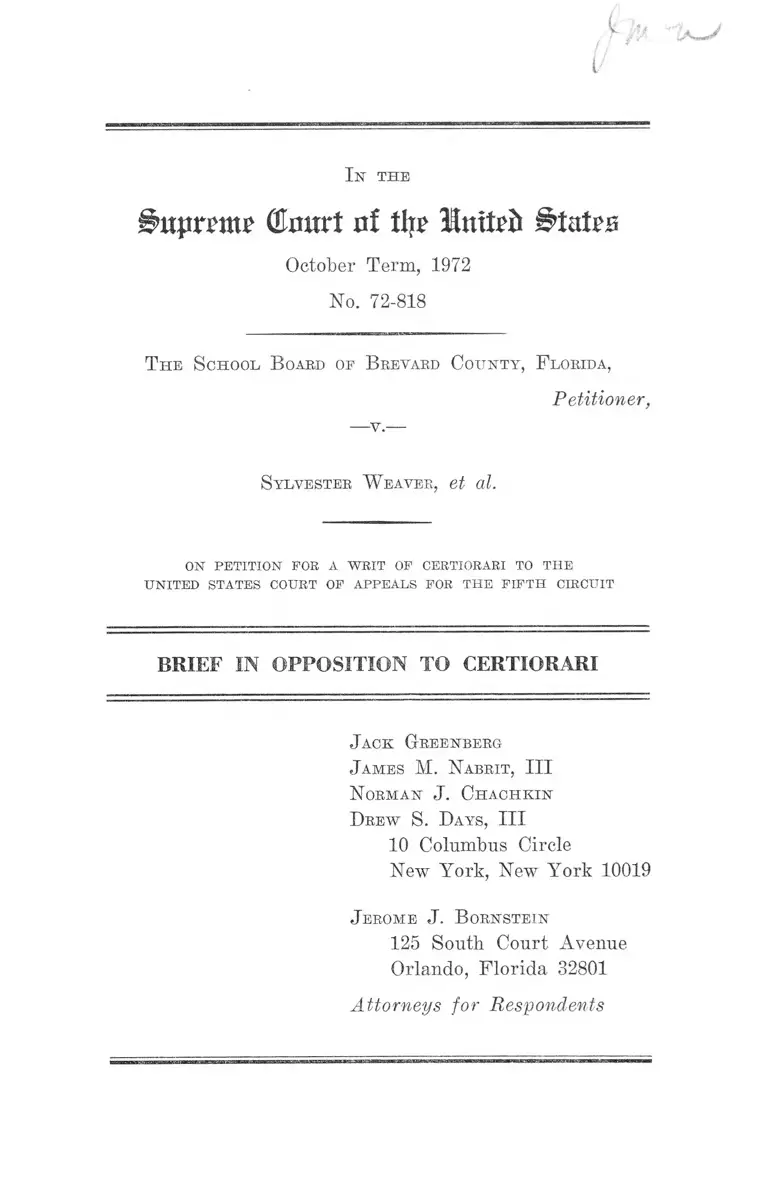

(ftmtrt of tty lutteft States

October Term, 1972

No. 72-818

T he S chool B oard op B revard C o u nty , F lorida,

Petitioner,

— v . —

S ylvester W eaver, et al.

ON PETITION POE A WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

J ack Greenberg

J ames M . N abrit, III

N orman J. C h a c h k in

D rew S. D ays , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J erome J . B ornstein

125 South Court Avenue

Orlando, Florida 32801

Attorneys for Respondents

1st the

(Emtrt of tlx? Mxutvh JsHatTB

October Term, 1972

No. 72-818

T h e S chool B oard of B revard C o u nty , F lorida,

Petitioner,

—v.—

S ylvester W eaver, et al.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Question Presented

Whether the court of appeals erred in refusing to permit

a school board to rely solely upon a majority-to-minority

transfer plan to desegregate a virtually all-black elemen

tary school where more effective techniques for desegregat

ing that school were available to the board.

Argument

On October 13, 1961, black parents and students (herein

after, “respondents” ) filed this lawsuit seeking an end to

the dual, racially-segregated school system in Brevard

County, Florida administered by the petitioner, the School

2

Board of Brevard County.1 At that time, Poinsett Elemen

tary was one of seven facilities in Brevard County at

tended exclusively by black students. Poinsett remained

all-black until the 1969-70 academic year when petitioner

was required by court order to implement a geographic

zoning plan to desegregate that facility. As a consequence,

23 white students joined 737 black students at Poinsett, re

ducing its enrollment from 100% to 96.9% black. In 1971,

petitioner was required to take further steps to desegregate

Poinsett. A majority-to-minority transfer plan was ap

proved by the district court for 1971-72 implementation.

Yet, as of March, 1972, Poinsett remained 97% black, only

100 of the approximately 800 blacks enrolled there having

exercised the right to transfer with space available and

free transportation. The court of appeals agreed with

respondents that the majority-to-minority transfer plan did

not represent an effective technique for desegregating

Poinsett.

Petitioner contends here that it has no affirmative con

stitutional duty to desegregate Poinsett further. This is so,

petitioner argues, first, because it is not required to achieve

racial balance in order to convert its dual system to a

unitary one. Second, the existence of one virtually all-black

school in its otherwise desegregated system does not, per

se, render that system unconstitutional. And third, the

majority-to-minority transfer approach constitutes an ac

ceptable technique for achieving greater desegregation.

Respondents do not quarrel with any of these assertions,

considered in the abstract. But there are constitutional

principles of equal importance relating to desegregation

which must be considered in conjunction with those relied

upon by petitioner. Racial balance is not the constitutional

1 Formerly called “the Board of Public Instruction of Brevard

County.”

3

objective; but school boards are under an affirmative duty

to achieve the “ greatest possible degree of actual desegre

gation.” Swann v. Charlotte-MecMenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 TJ.S. 1 (1971). The continued existence of all-blacli

or virtually all-black schools can be condoned only where it

has been established that no feasible alternatives are avail

able to destroy the one-race character of such schools.

Swann, supra. School boards may not rely upon majority-

minority transfer plans to desegregate one-race schools

where other more effective techniques exist, And school

boards have a heavy burden to bear in justifying reliance

upon manifestly less effective alternatives in dismantling

dual systems. Green v. School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968).

The court of appeals correctly applied this second set

of principles in rejecting petitioner’s majority-to-minority

transfer plan for desegregating Poinsett. For it found that

Poinsett was surrounded by at least six virtually all-white

elementary schools which could be paired or clustered with

Poinsett to desegregate that facility. The distances between

Poinsett and these schools are as follows:

Grolfview 1.2 miles

Cambridge — 2.2 U

Mila — 3.0 a

Anderson 3.5 Cl

Tropical 4.2 cc

Audubon 5.6 cc

The feasibility of pairing or clustering Poinsett with these

schools was established by several facts. Petitioner had

previously submitted a desegregation plan for Poinsett

that would have converted it to a special education center

to which children from not only the nearby six schools

mentioned above, but from all the schools in the county,

4

would have been sent on a weekly rotation basis. And, the

majority-to-minority transfer plan implemented by peti

tioner for the 1971-72 academic year envisioned that Poin

sett students would be eligible to attend any of the six

schools nearest that facility.

Hence that court concluded that petitioner had not

achieved the greatest possible degree of actual desegrega

tion, that Poinsett remained all-black despite the avail

ability of more effective desegregation techniques, and that

nothing in the record served to justify petitioner’s prefer

ence for a patently less effective desegregation approach.

Petitioner has presented nothing to this Court that dis

credits in any respect these findings of the court below.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N o r m a n J . C h a c h k in

D rew S. D ays, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J erome J . B ornstein

125 South Court Avenue

Orlando, Florida 32801

Attorneys for Respondents

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. «SH^> 219