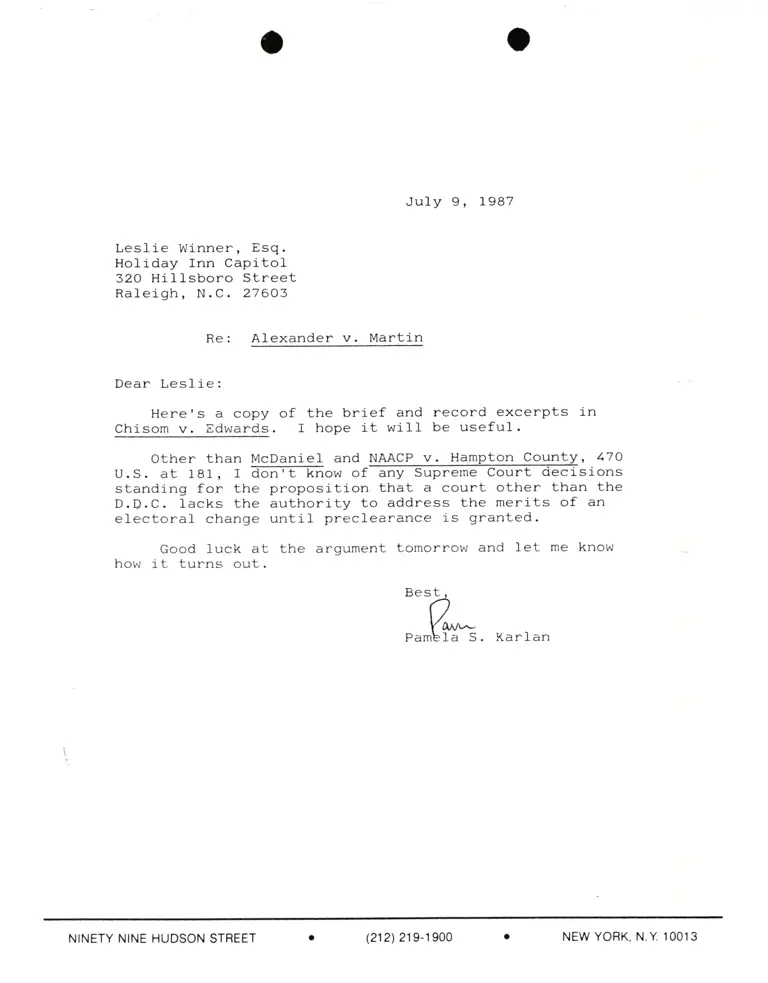

Correspondence from Pamela Karlan to Leslie Winner, Esq. Re Alexander v. Martin

Correspondence

July 9, 1987

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Pamela Karlan to Leslie Winner, Esq. Re Alexander v. Martin, 1987. d15b29d5-eb92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9aa68c29-26db-4945-b2aa-77067904b892/correspondence-from-pamela-karlan-to-leslie-winner-esq-re-alexander-v-martin. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

JuIy 9, 1987

LesIie Winner, Esq.

Holiday Inn Capitol

32O HiIlsboro Street

Raleigh, N.C. 27603

Re: Alexander v. Martin

Dear Leslie:

Here's a copy of the brief and record excerpts in

Chisom v. Edwards. I hope it wilt be useful.

Other than McDaniel and NAACP v. HaqP-lon County, 47o

U.S. at l-81 , r tffiow of sions

standing for the proposltion that a court other than the

D.D.c. lacks the authority to address the merits of an

electoral change until preclearance is granted.

Good luck at the argument tomorrow and let me know

how it turns out.

""^A*. Karran

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET . 12,12\ 219-1 9OO O NEW YOBK, N. Y 1OO1 3