Jackson v. United States Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. United States Brief for Appellants, 1964. 84f409ec-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9b08a686-fc3e-4c03-a39b-9b4d4bb850fb/jackson-v-united-states-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

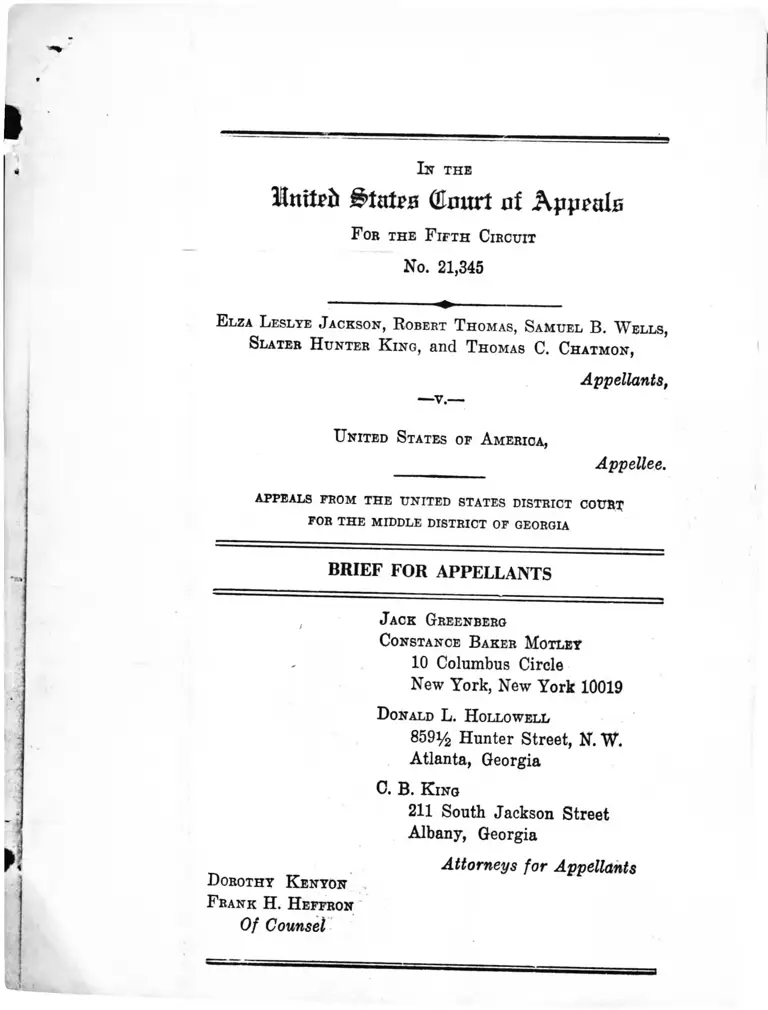

I n THE

•Untteii States ©ourl of Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 21,345

E lza Leslye J ackson, R obert T homas, S amuel B. W ells,

Slater H unter K ing, and T homas C. Chatmon,

Appellants,

U nited S tates of A merica,

Appellee.

APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

, J ack Greenberg

Constance B aker Motley

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

D onald L. H ollowell

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

C. B. K ing

211 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

D orothy K enyon

F rank H. H effron

Of Counsel

-31121—2 Pr oofs—1M0-G4

I n the

TUnxttb Stairs dnurt of Appeals

F ob the F ifth, Circuit

No. 21,345

E lza Leslte J ackson, Robert T homas, S amuel B. W ells,

S later H unter K ino, and T homas C. Chatmon,

— y . —

Appellants,

U nited S tates of A merica,

Appellee.

appeals from the united states district cou&t

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement

The appellants in these five cases were indicted and con

victed for violation of 18 U. S. C. §1621, the perjury statute.

The cases arose from testimony given by the appellants

before the grand jury of the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Georgia on August 5, 1963 con

cerning an alleged meeting in the office of Attorney C. B.

King in Albany, Georgia, on July 30, 1963. Appellants

Thomas and Wells were charged with having testified

falsely that they did not attend the meeting (R. 404, 561).

Appellants Jackson and Slater King were charged with

having testified falsely that they did not recall attending

the meeting (R. 1, 824). Appellant Chatmon was charged

2

in two counts, for having testified falsely that he did not

recall attending and that he did not attend (1097).

The appellants were indicted August 9, 1963. All pleaded

not guilty September 30, 1963 (R. 2, 405, 562, 825, 1099).

On the same day identical motions to dismiss were filed

in all cases alleging inter alia that the

. . . indictment was found by a Grand Jury whose

members were selected on a basis which violated the

due process clause of the Fifth Amendment of the

Constitution of the United States, and Section 1863

of Title 28 United States Code in that race was a

factor used in the selection of the members of the

Grand Jury.

Hearing on this portion of the motions to dismiss was

held in the Macon Division on October 17, 1963 (R. 217)

before Judge Bootle. It was stipulated that certain testi

mony given at a similar hearing before Judge Elliott of

the District Court for the Middle District of Georgia

in the case of United States v. William G. Anderson, Crim

inal No. 2222, Albany Division, on October 3, 1963, would

be adopted as a part of the record in these five cases (R.

219-20). This testimony is printed in the record at pages

99-182. A stipulation concerning participation of Negroes

on state court juries in counties comprising the Macon

Division (R. 71), which had been entered in the Anderson

case on October 3, 1964 was made a part of the record

in these five cases (R. 221-22), as was a similar stipula

tion of October 17, 1963 (R. 85) prepared specifically for

these cases (R. 221-22). At the hearing before Judge

Bootle, reference was also made to the government’s re

sponse to the motion to quash in the Anderson case (R.

2 2 3 - 2 4 response and^ accompanying exhibits are

printed infra as Aft Appendix to this brief. Judicial notice

A *

3

was taken of the 1960 United States Census figures relating

to adults of both races in the counties comprising the Macon

Division (R. 224).

The motions to dismiss \tare denied October 22, 1963 (R.

64). On November 18, 1963, the five defendants filed a mo

tion to quash the petit jury panel on the ground that

Negroes were systematically excluded from jury service

in violation of constitutional and statutory rights (R. 257).

The motion was overruled in open court on the same day

(R. 1112).

Each case was tried separately before a jury. At the

close of the government’s evidence in each case, the de

fense moved for an acquittal on the ground that the evi

dence was insufficient to sustain a guilty verdict (R. 348,

490, 713, 974, 1317). Each motion was overruled (R. 349,

490, 728, 976, 1317). In each case the jury rendered a ver

dict of guilty (R. 2, 405, 562, 825,1100), and in the Chatmon

case on both counts (R. 1100). On December 23, 1963,

appellants King (R. 1088) and Wells (R. 814) were sen

tenced to imprisonment for a year and a day; appellants

Thomas (R. 547) and Chatmon (R. 1446) were given sus

pended sentences, with five years probation. On February

28, 1964, appellant Jackson was given a suspended sen

tence, with three years probation (R. 391). Notice of

appeal was filed on the same day as judgment and sen

tence in all five cases (R. 393, 554, 820, 1093, 1451).

The facts in these cases are closely related, but because

there were significant variations in the evidence at the five

trials, detailed discussion will await analysis of the evi

dence in the Argument. Only the background is supplied

here.

-— July and August^the Grand Jury of the United

States D istncr^m rrrT orthe Middle District of Georgia

4

was investigating the activities of the Albany Movement,

a well known civil rights organization, with respect to the

picketing of Carl Smith’s} store in Albany. Smith had been

a member of a jury which decided a case adversely to a

Negro. The grand jury was investigating the possibility

that the picketing constituted an obstruction of justice un

der 18 U. S. C. §1503 (R. 475). Several persons associated

with the Albany Movement were subpoenaed to appear be

fore the grand jury on July 31, 1963. The five appellants

were among these persons.

On July 30, 1963, a number of those who had been sub

poenaed appeared at various times in the office of Attorney

C. B. King between 4:00 and 6:30 p.m. Attorney King’s

law clerk, Miss Elizabeth Holtzman, gave a talk on federal

grand juries, and some discussion of the subject followed.

On August 5, 1963, the appellants appeared before the

grand jury and were asked, with varying degrees of

specificity, about their participation in this gathering.

These indictments followed.

The facts regarding jury selection, brought out at the

hearing of October 17, 1963, are as follows:

The Macon Division of the Middle District of Georgia

covers 18 counties with an adult population in 1960 of

211,306, of whom 73,014 or 34.5 per cent were Negro (App.

2a, App. B). The federal jury list, from which all grand

and petit jurors are taken (R. 108), contains 1,985 names,

including only 117 Negroes, or 5.8 per cent (R. 223, App.

2a).1 This list was compiled in 1959 and has not been

revised significantly since then (R. 111). On the previous

federal jury list, there were 1,837 names including 137

Negroes, or 7.45 per cent at a time when Negroes repre-

1 Of the 1,985 persons on the jury list, the race of only 5 is

unknown (App. 16a).

5

scnted approximately 38 per cent of the population.2 In

1940, 45.1 per cent of the population of the Division was

Negro, but only 3.21 per cent of those on the federal jury

list were Negroes.3

The federal figures correspond closely to those of iurg-

lists of state courts in the same -eightee^counties. Among

the 13 counties for which complete figures are available,

there are 3,889 persons on grand jury lists, including only

57 Negroes or 1.5 per cent (R. 96). In 11 counties no

Negro ever served on a grand jury (R. 87). In the 10

counties from which figures were obtained, there '^©rjp'^103

persons on the traverse jury lists, but only 182 Negroes,

or 2.56 per cent (R. 94-95).

Q j^

The 1959 federal jury list was compiled by Mr. John P.

Cowart, Clerk of the Middle District, Mr. Walter Doyle,

Deputy Clerk, and Mr. William P. Simmons, Jury Commis

sioner, all of whom are white. The starting point was the

1952 federal jury list (R. 112), which had been revised

only in 1957 to add some women’s names (R. 111). On the

1952 list, red c’s appeared after the names of some Negroes

(R. 112). The 1959 revision was accomplished in the same

manner as previous revisions. Mr. Doyle went into each

county with a copy of the 1952 list and checked with local

court officials on the status of jurors on that list (R. 109,

141-142). Those who were no longer eligible for jury ser

vice because of death, disability, change of residence or

2 Brief for Appellant, Rabinowitz v. United States, Fifth Cir

cuit, No. 21,256, 1964, citing pp. 93a, 289a of the record. This

Court may take judicial notice of its own records. Lunsford v.

Comm’r of Internal Revenue, 212 F. 2d 878, 881 (5th Cir. 1954);

Tucker v. National Linen Service Corp., 200 F. 2d 858 (5th Cir.

1953), cert, denied, 346 U. S. 817; Ellis v. Cates, 178 F. 2d 791

(4th Cir. 1949), cert, denied, 339 U. S. 964. The Rabinowitz case

was heard in the same district court as these cases (R. 223).

3 Brief for Appellant, Rabinowitz v. United States, Fifth Cir

cuit, No. 21,256, 1964, citing p. 94a of the record.

6

some other reason were crossed off (R. 139). Mr. Doyle

also sought new names from county officials and the records

shown to him (R. 142). Independently, Mr. Cowart and

Mr. Simmons sought new names from various sources.

Questionnaires were sent to all persons whose names had

been obtained by these three men (R. 130, 160). Each new

person’s qualifications were checked according to his an

swers on the questionnaire, and those found qualified were

added to the remaining names on the previous list (R. 134,

174). The questionnaire .jPreparBiijith the aid o f Judge

Bootle (R. 134), asked tne race of each prospective" juror

(R. 115, App. 8a).

Mr. Doyle, the only official who systematically travelled

from county to county, customarily spoke with persons “in

the Clerk’s office, the Sheriff’s office, the Ordinary’s office,

the tax office, any group I could find” (R. 141), in his search

for new jurors. The local clerk “in ’most every case” would

go through the local jury list with Mr. Doyle (R. 142).

In at least 17 of the counties, the lists of property owners

in the Tax Receivers’ offices are either segregated by race

or contain c’s after the name of Negroes (R. 91-92). Mr.

Doyle also spoke to businessmen and “ladies who work in

offices” in the counties (R. 145). He claimed that he made

“a particular effort” to obtain Negro names as well as white

(R. 144), but when asked to “explain in detail how you have

gone about getting these Negro names for the jury list,”

Mr. Doyle failed to mention that he had spoken to a single

Negro (R. 144-45).

Mr. Cowart stated that the state court jury lists were

basic sources of new names for the federal list (R. 108).

He added names by asking people he knew (R. 110), but

“other than my own friends, I didn’t make any contacts

out of [Bibb] County. I sent Mr. Doyle to make those

contacts” (R. 110). Mr. Cowart could not remember the

7

name of the only Negro from who he had ever sought names

of prospective jurors outside of Bibb County (R. I l l , 120).

He did list five Negroes from whom he asked names in

Bibb County, all of whom he knew in a business capacity

(R. 121-22). He also claimed that he had white friends in

other counties who supplied him by mail and telephone with

the names of both whites and Negroes (R. 131, 134-135).

When asked why it was that most of his sources were

connected with the legal profession, Mr. Cowart said, “I

know more people amongst that walk of life than I do

amongst the Negro race and so that’s where I have to get

my information” (R. 135).

Mr. Simmons, the Jury Commissioner, also added names

which he received from his acquaintances (R. 157). He said:

I inquired, naturally, of people that I knew and

whose reputation I knew. So quite undoubtedly I was

confining myself to people whose integrity and char

acter I respected and whose judgment I would have

respect for. They were people mostly whose paths

I happened to cross occasionally in a business way . . .

including civic work and various things of that sort.

* # • • •

. . . my contacts were heavier, of course, with the

white race because my association was greater with

that particular group, but there certainly was no effort

to concentrate exclusively on any one segment of the

population (R. 158).

Mr. Simmons claimed that he asked both whites and Negroes

for the names of persons of both races (R. 158), but he did

not mention by name any Negro to whom he had spoken

on this matter. Mr. Simmons set very high standards of

reputation, integrity, and intellect for prospective jurors

(R. 157, 158, 159, 161, 166, 172, 173). “We wanted an out-

8

standing blue ribbon jury list . . . ” (R. 173). When asked

if he had spoken with any Negroes in Hancock (R. 166-67),

Peach (R. 167-68), Crawford (R. 171), Twiggs (R. 170)

or Jasper (R. 171) Counties, all having a high proportion -

of Negroes, Mr. Simmons stated that he had not. “Unfortu

nate as it may be, I think the Negro community in those

counties does not qualify on the grounds that we set up,

of intelligence, integrity and ability to serve on those

grounds alone” (emphasis added) (R. 177).

Five Negroes served on the grand jury of 23 which

indicted the appellants (R. 144). Mr. Doyle could recall

no other grand jury since 1937 which included as many

as 5 Negroes (R. 147). The testimony concerning service

of Negroes on petit juries in the Macon Division was not

definite. Mr. Cowart stated that he had seen at least one

Negro on almost every jury that he had observed (R. 104),

but he could recall only two specific instances since the

1930’s (R. 107). In these jgt^'cases, ail Negroes^ were chafT""”"̂

lenged by the government, and appellants were tried by 5

all white petit juries (R. 418).

dismiss the indictments and the motion to quash the petit

jury panel on the ground that Negroes were systematically

from jury service.

1 on the ground of insufficiency of the evide;

the Wells case, the district court erred in overruling

is based on the attorney-client privilege.

Specifications of Error

1. The district court erred in denying the motions to

le district court erred in denying the motior

9

A R G U M E N T

' I.

The Grand Jury That Indicted These Five Negro Ap

pellants and the Petit Juries That Found Them Guilty

Were Drawn From a List Which Included Only a Token

Number of Negroes and Was Compiled in a Manner In

consistent With Due Process of Law and Other Rele

vant Federal Standards.

Few principles of fundamental law have required judi

cial application more often than the one controlling these

cases—that systematic exclusion of Negroes from the grand

or petit jury requires reversal of the conviction. See, e.g.,

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, Arnold v. North

Carolina, 376 U. S. 773. Most of the cases have been de

cided under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, which binds the states. These five cases come

under the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment, 28

U. S. C. §1863(c),4 and rules laid down by the Supreme

Court governing the selection of juries in federal courts.

A. Constitutional Standards of Jury Selection Have Been

Violated, Resulting in Only Token Inclusion of Negroes.

Appellants’ case begins with the wide disparity between

Negro representation in the population of the 18 counties

in the Macon Division and the token numbers of Negroes

on the federal jury list. Negroes constitute 34.55 per cent

of the adult population but less than 6 per cent of those on

the jury list. In Speller v. Allen, 334 U. S. 443, where 38

per cent of the population but only 7 per cent of those on

4 28 U. S. C. §1863 (c) provides, “No citizen shall be excluded

from service as grand or petit juror in any court of the United

States on account of race or color.”

10

the jury list were Negroes, the Supreme Court required an

explanation by those who denied discriminating, and the

Court affirmed only because a nondiscriminatory method of

selecting jurors was shown to have been followed.

Even more shocking than the statistics, however, is the

evidence on the methods used by the federal officials in the

Macon Division to select persons for the jury list. One

vice of the system sufficient to require reversal under

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282; Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S.

400; and United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F. 2d

53 (5th Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 372 U. S. 924, is the reliance

of the Clerk, Deputy Clerk and Jury Commissioner on the

recommendations of their white friends. Although these

officials were responsible for finding eligible jurors in

eighteen counties, none of them sought names from any

Negroes, with one possible exception (R. I l l ) , in any of

the ■ggwntean^counties outside of Bibb County. Surely,

their claims that they always asked their white sources for

Negro names as well as white names fall far short of ex

cusing their dereliction of duty in not developing sys

tematic methods of gathering the names of Negroes as

well as whites. This Court is aware of conditions in segre

gated, Deep South communities, see Whitus v. Balkcom,

■333 F. 2d 496_X5th Cir._19^4); United States ex rel. Goldsby

v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d 7 r (5th Cir. 1959), cert, denied, 361

U. S. 838; it cannot be presumed that a white jury com

missioner’s white friends will provide a fair distribution

of white and Negro jurors.

Another practice of the federal officials that operated

with particularly discriminatory effect against Negroes

was the use of state court jury rolls in the 18 counties.

These rolls contained so few Negro names, approximately

2 per cent (R. 86, 94-95), that their use was as unaccept

able as the practice condemned in Seals of taking names

11

from membership lists of white organizations. In fact, the

grand jury lists in 6 counties were totally barren of Negro

names (R. 86), and some of these counties had the highest

' percentages of Negroes in their population (App. B). These

state court jury rolls were considered by Mr. Cowart to be

a basic source of names for the jury roll (R. 108).

All of the sources used by the federal officials were seri

ously weighted against the Negro. The 1952 federal list,

which formed the basis for the 1959 revision, had only a

minimal percentage of Negroes. The county officials with

whom Mr. Doyle checked were white. The county jury rolls

were almost completely restricted to white persons. Mr.

Cowart’s friends in the outlying counties, whom he con

tacted by mail and telephone, were white; the Negro ac

quaintances whom he contacted in Bibb County included

only a doorman, funeral director, tailor, and home demon

stration agent. Mr. Simmons, relying on his reputable

friends in all 18 counties, acknowledged that he had to rely

on white persons to supply names. No wonder there was

a disparity between Negro representation in the popula

tion and the incidence of Negro names on the jury roll I

Appellants established the existence of a discriminatory

selection system producing discriminatory results. There

being no need to prove intentional discrimination, but only

a system operating in a discriminatory manner, Hill v.

Texas, 316 U. S. 400, Akins v. Texas, 325 U. S. 398, United

States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F. 2d 53 (5th Cir. 1962),

appellants have carried their burden. But that does not

complete their case, for this record offers uncontrovertible

proof that the opportunity for discrimination was built

into the jury system.

No juror is placed on the list until he has submitted a

questionnaire containing a space for designation of race.

This questionnaire was used in the 1959 revision, and the

12

questionnaires of all 1985 jurors on that list are presently

on file in the clerk’s office (App. la). Only 5 failed to fill

in the racial blank (R. 16a). This means that each pro

spective juror’s race is known when his qualifications are

being passed upon, and, further, that any juror’s race can

be ascertained at any time. In Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S.

559, where pink and wffiite cards were used to differentiate

Negro and white jurors, the Supreme Court reversed with

out evidence that state officials availed themselves of this

opportunity for discrimination. It was enough that the

practice made “it easier for those to discriminate who

[were] of a mind to discriminate.” 345 U. S. at 562.

Since the questionnaires cover all jurors, it is unneces

sary to mention other racial markings, but their pervasive

ness is revealing. Red c’s were found on the 1952 jury list.

When confronted with this reality by defense counsel, Mr.

Cowart explained that Negroes’ names were marked when

they appeared in the courtroom and that he still followed

the practice (R. 112). On cross-examination by friendlier

government counsel, he expressed amazement at the mark

ings and disclaimed any connection with them (R.> 124-25).

It is also of some significance that state traverse jury rolls,

which are used by Mr. Doyle to gather names, are required

by Georgia law to be taken from tax lists, Ga. Code Ann.

§59-106, which are kept on a segregated basis in at least

17 counties in the Macon Division (R. 91-92). Under the

recent decision in Hamm v. Virginia State Board of Elec

tions, 230 F. Supp. 156 (E. D. Va. 1964), aff’d ----- U. S.

----- , 33 U. S. L. Week 3151 (October 26, 1964), the prac

tice of keeping segregated tax and voting records violates

the Fourteenth Amendment.

The appellants have established a prima facie case of

discrimination, which the Government has not adequately

rebutted. Its only evidence was the testimony of Jury

Commissioner Simmons, who stated that a smaller per

centage of Negroes than whites were qualified for jury

service (R. 176). From his reading of the newspapers and

general knowledge he had concluded that there was in

finitely more illiteracy amon£ the Negro group” (R. 174).

Although he recited his educational credentials, member of

the Bibb County Board of Education and the Governor s

Committee on Efficiency and Economy and trustee of Wes

leyan College (R. 175), Mr. Simmons offered no figures

to support his generalized conclusions and acknowledge

that he had made no serious study of the situation (R. 177).

Moreover, his testimony is considerably weakened by the

admission that he had not spoken with any Negroes con

cerning jury service in many of the counties where the

most Negroes resided (R. 166-72). He was satisfied that the

“Negro community” did not qualify according to his stand

ards (R. 172), which, incidentally, were considerably higher

than the jury qualifications set forth in 28 U. S. C. §1861;

he did not seem to be concerned about whether Negro indi

viduals were qualified. Finally, in opposition to Mr. Sim

mons’ vague statements was the testimony of Mr. William

Randall, a contractor who knew many Negroes in the 18

counties. He stated that many Negroes in those counties

were qualified for jury service (R. 150-54).

Nor has the government justified the jury system in the

Macon Division by showing that 5 Negroes were on the

grand jury that indicted appellants (R. 144). A jury-

system cannot be judged according to the racial composi

tion of a single grand jury ; if it could, a Negro could claim

discrimination whenever no Negroes were on his jury no

matter how fairly the system was administered. The rele

vant consideration is that only 5.89 per cent on the jury

roll were Negroes as the result of a discriminatory selection

process. In that situation the appearance of 5 Negroes on

a grand jury of 23 could be expected to occur only very

13

14

rarely. In fact, Mr. Doyle, Deputy Clerk since 1937, could

recall no previous instance in which there were 5 or more

Negroes on a grand jury (R. 147). As this Court ruled in

Collins v. Walker, 329 F. 2d 100 (1924), cert, denied,-----

U. S. ----- , 33 U. S. L. Week 3169 (November 9, 1964),

the deliberate inclusion of Negroes is as discriminatory

and invalid as systematic exclusion. See also Cassell v.

Texas, 339 U. S. 282, 287.5

B. The Grand and Petit Juries W ere Not Selected in

C onform ity W ith Standards of Procedural Fair

ness A pplicable in Federal Courts.

This case, having been tried in a federal court, is gov

erned by principles laid down by the Supreme Court in

the exercise of its “power of supervision over the adminis

tration of justice in the Federal courts.” Thiel v. Southern

Pacific Co., 328 U. S. 217, 225. As Justice Jackson wrote

in Fay v. New York, 332 U. S. 261, 287, “Over federal pro

ceedings we may exert a supervisory power with greater

freedom to reflect our notions of good policy than we may

constitutionally exert over proceedings in state courts,

and these expressions of policy are not necessarily em

bodied in the concept of due process.”

Decisions of the Supreme Court have firmly established

the principle that federal juries must be fairly drawn from

a cross-section of the community. Thiel v. Southern Pacific

Co., supra; Ballard v. United States, 329 U. S. 187; Glasser

v. United States, 315 U. S. 60. There can be no exclusion

of economic, social, religious, racial, political, or geo

graphical groups. “Recognition must be given to the fact

that those eligible for jury service are to be found in

v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U. S. 217, a case tried in a

federal court, held that the presence on the jury of 5 members

of the working class could not defeat a challenge to the jury

system orj thq ground that such persons were excluded.

every stratum of society.” Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co.,

328 U. S. at 220. The record in these f iw ^ se s discloses

a total disregard of this mandate. r* —----------

Jury Commissioner Simmpns insisted on finding jurors

who met high standards of reputation, integrity, and in

tellect (R. 157, 158, 159, 161, 166, 172, 173). “We wanted

an outstanding blue ribbon jury list . . . ” (R. 173). These

standards bear virtually no relation to the qualifications

of federal jurors set out in 28 U. S. C. §1861, as amended

by the Civil Rights Act of 1957. Mr. Simmons was under

the impression that it was his duty to seek only the “best”

jurors (R. 172). This is understandable in view of the

fact that Georgia jurors must be “the most experienced,

intelligent, and upright citizens,” Ga. Code Ann. §59-106,

and before 1957 federal jurors had to meet state require

ments.6 However, it does not excuse the Jury Commis

sioner. It was his job to select jurors representing a cross-

section of the community. By failing to do so he excluded

Negroes and probably a great many white persons of the

lower social, economic and intellectual groups. Whether

this exclusion was intentionally discriminatory or the re

sult of misplaced conscientiousness, the harm to the jury

system is the same. Glasser v. United States, 315 U. S. at

86; Dow v. Carnegie Illinois Steel Corp., 224 F. 2d 414,

424 (3rd Cir. 1955).

15

6 Since the 1959 federal jury list included all persons on the

1952 list who had not become disqualified (R. 134, 174), it is

evident that the present (1959) federal list consists in large part

of names chosen according to the Georgia law on jury qualifica

tion law. None of the federal officials indicated any change in

their selection procedure following 1957. It may be concluded,

then, that the present federal jury list reflects no effort to obtain

a crpss-section of the community.

•hfiOATE-

16

II.

In the King and Jackson Case? the Evidence Was In

sufficient to Sustain a Guilty Verdict.

A. Appellant Slater King

The statements of appellant Slater King before the grand

jury which are alleged to have been false are the following:

Q. Have you attended any mass meeting or meet

ing where one or more people were in attendance,

where it was being discussed about the fact that cer

tain ones were going to have to appear before the-

grand jury in Macon, Georgia? A. I don’t recall

(R. 960).

* • * # •

Q. I would like to ask you if you have attended any

type of meeting or any type of get together during the

week of July 29, 1963 through August 2, 1963 wherein

or wherein others discussed the fact that this grand

jury was in session here in Macon, Georgia? A. I

don’t recall doing so (R. 962).

In order to convict there must have been sufficient evi

dence for the jury to conclude beyond a reasonable doubt

that there was a meeting of persons in the office of C. B.

King on July 30, 1963 who discussed testimony to be given

before the grand jury; that Slater King was present at that

meeting and at the time thought of himself as being in at

tendance at and participating in the meeting; that while

testifying before the grand jury Slater King remembered

having attended the meeting and falsely testified that he

did not recall attending. In a perjury case, the govern-

ment’s burden of proof is extremely heavy. Paternostro v.

United States, 311 F. 2d 2 9 8 ^ rd Cir. 1962). In a case of

this type, where several elements of proof relate to the de-

17

fendant’s state of mind, the evidence must be particularly

strong. Fotie v. United States, 137 F. 2d 831 (8th Cir.

1943). The evidence before the jury in Slater King’s trial

falls far short of that requirement.

The government presented three witnesses. The first was

Mrs. Butler, the secretary of Attorney C. B. King. Mrs.

Butler outlined the general situation in C. B. King’s office

on the afternoon of July 30, 1963, describing the physical

properties of the office 6 and stating how many persons were

in the office and for what purposes, but she gave practically

no testimony that in any way incriminated Slater King.

She testified that Slater King arrived at the office between

5:15 and 5:30 and remained there for a period of 10 or 15

minutes (R. 866). Mrs. Butler stated that during the hours

following 4:00 o’clock on that afternoon, there were between

6 and 18 persons in the office of C. B. King, including some

who had been subpoenaed to appear before the grand jury

(R. 868). Mrs. Butler explained that she called Slater

King, the brother of Attorney C. B. King, requesting him

to bring some chairs to the office (R. 869) as she had done

on occasions in the past (R. 886). In response to her call

Slater King and others did take a number of chairs to C. B.

Kings office (R. 869). Mrs. Butler stated that at the time

Slater King was in the office appellant Jackson, appellant

Thomas, one Emma Perry, one Sego Gay and Miss Holtz-

man were present in the office, as were six or seven trustees

of Mount Olive Baptist Church, including Mrs. Dora White

(R. 877-880). Mrs. Butler also testified that during the

afternoon, Miss Holtzman addressed a number of them in

the inner office of C. B. King on the rights of witnesses ap

pearing before federal grand juries (R. 871). She did not

state that Slater King was present during this talk.

' Attorney C. B. King’s office consisted of two rooms, a reception

his secretary worked and Attorney King’s inner office

18

Mrs. Butler testified that two conferences had been sched

uled for the afternoon of July 30, 1963, one with the trus

tees of Mount Olive Baptist Church concerning recovery of

money resulting from the burning of their church and one

scheduled with Thomas Chatmon, the purpose of which she

did not recall (R. 881). Attorney C. B. King had spoken on

the telephone to Mrs. Butler and to Miss Holtzman asking

Miss Holtzman about the research that she had done on

grand juries (R. 883-84). Mrs. Butler also stated that Miss

Holtzman’s research on grand juries was the subject of the

afternoon conference which was held (R. 884).

On cross-examination, Mrs. Butler stated that she called

Slater King at approximately five o’clock and requested

him to bring the chairs, but had not discussed the subject

matter of any meeting being held (R. 886). She also stated

her belief that at the time Slater King arrived in the office,

Miss Holtzman had finished her talk about grand juries

(R. 886). Mrs. Butler twice repeated her testimony that

Slater King was there from 10 to 15 minutes (R. 887, 892).

She also stated that while in the office Slater King received

three telephone calls (R. 890) and that he had spoken with

a Mr. Edwards about the problems of the Mount Olive

Baptist Church (R. 891). She also stated that she did not

remember Slater King having said anything in particular

to anyone in C. B. King’s inner office (R. 892).

Mrs. Butler’s testimony establishes at the most that a

number of persons were in the inner office of C. B. King

listening to a talk on federal grand juries by Miss Holtz

man and discussing the subject and that for a short time

Slater King was in some part of Attorney C. B. King’s of

fice. Her testimony explains the reason for Slater King’s

visit and in no way indicates that Slater King participated

in the gathering in the inner office or that he did anything

to lead him to believe that he had attended a meeting.

19

The government’s second witness was Edward Bryant,

Jr. He testified that he arrived at C. B. King’s office at

approximately 4 :45; that while he was there a white girl

read something off a paper; that he remained forty minutes

and that Slater King was present in the office during Bry

ant’s entire stay (R. 899-904). He did not state specifically

that Slater King was in the inner office where the confer

ence was proceeding. Bryant remembered some persons

talking during the discussion while he was there, but he

did not remember Slater King’s having spoken with anyone

(R. 913). An extremely nervous witness, Bryant had diffi

culty making himself heard (R. 906).

Bryant’s testimony can be considered incriminating in

only one respect; his statement that Slater King was in

C. B. King’s office for at least forty minutes could tend to

indicate that Slater King’s time was not taken up entirely

with setting up chairs, speaking with trustees of the burned

church, and receiving and making telephone calls. How

ever, Bryant’s testimony conflicts very strongly, not only

with King’s testimony in behalf of himself, but with the

two chief witnesses of the government, Mrs. Butler and

Miss Holtzman. Mrs. Butler testified three times that

Slater King was in the office for 10 to 15 minutes (R. 866,

887, 892). Miss Holtzman testified that Slater King was

there for 15 to 20 minutes or possibly a few minutes more

(R. 937-38). Certainly, the government is not at liberty to

select bits and pieces from the conflicting testimony of its

three witnesses in order to make out its highly circumstan

tial case. See McWhorter v. United States, 193 F. 2d 982

(5th Cir. 1952).

The third government witness was Miss Elizabeth Holtz

man, law clerk to Attorney C. B. King. She stated that a

conference or a series of appointments was scheduled for

*

20

'V>

< \0

the afternoon of July 30, 1963; that she had spoken on the

telephone with Attorney C. B. King about her research and

the subject of the conference, which was the functions and

structure of the federal grand jury (R. 925-927). She did

not state that any appointment had been made for Slater

ing during that afternoon.

testified that Slater King arrived at apppomr

p.m. She was constantly in C. B. King’s inner office

at all relevant times and when she saw Slater King he was

in the inner room (R. 933-934). Slater King was not in the

office before he brought up the chairs pursuant to Mrs.

Butler’s request (R. 940). Miss Holtzman remembered no

conversation with Slater King. She stated that he probably

was speaking to people around him, but that she could not

definitely remember and she did not mention any subject

of conversation (R. 940). She testified that Slater King

was in Attorney C. B. King’s office (whether she meant the

inner room as opposed to the office consisting of two rooms

was not brought out) for a period of 15 to 20 minutes or

possibly a few minutes more (R. 938, 940). She also stated

that he received some telephone calls (R. 941).

Completely lacking from this case is any direct testimony

that Slater King was in the inner office of Attorney C. B.

King for any appreciablewlength of time or that he spoke

with anyone concerning the appearance of witnesses before

the grand jury or that he heard others discussing this sub

ject. In fact, there iaTSroof that he was informed of the

5ose of the gathering in Attorney C. B. King’s office on

the afternoon of July 30, 1963. This alone, of course, suffi

ciently demonstrates the utter inadequacy of the evidence

presented by the government.

What makes the case even more suspect, of course, is the

absence of specificity in the questions asked of Slater King

before the grand jury. He was not asked whether he was

/■"i

. A

21

in the office of his brother during that afternoon, or why he

had gone there, or for how long he had remained, or whom

he had seen or with whom he had spoken. He was asked if

he had attended a meeting during which it was discussed

that certain persons werd going to have to appear before

the grand jury. Neither of the relevant questions asked

him before the grand jury made any specific reference to

the afternoon of July 30, 1963.

Everything in the record is consistent with Slater King’s

own testimony during his trial. He stated that he was in

his brother’s office for between 15 and 23 minutes; that he

had been called and requested to take some chairs; that he

had done so, making two or three trips with chairs; that

he engaged in perfunctory, casual conversation with vari

ous persons in the office, including some trustees of the

burned church; and that he received and made several tele

phone calls (R. 979-81). He stated, “I have no recollection

as to whether anyone discussed with me as to the grand

jury hearing in Macon” (R. 981). When asked if he ever

considered himself as being in attendance at any meeting

in the office he responded:

No not at all, because there was no one who was keep

ing minutes; there was no privacy; the door was com

pletely open into the anteroom; there was people mov

ing and getting up; and I did not consider myself at a

meeting of any kind because I didn’t go for a meeting.

I went for one purpose, to take the chairs, to get back

to the office because there were people waiting on me

there (R. 983).

Slater King testified that he sat down in the inner office

for a short time but did not consider himself participating

in any meeting (R. 984-85). Several character witnesses

testified as to his veracity (R. 1018-26).

The evidence presented by the government must exclude

every other hypothesis than that of the defendant’s guilt.

Paternostro v. United States, 311 F. 2d 298 (5th Cir. 1962);

Beckanstin v. United States, 232 F. 2d 1 (5th Cir. 1956);

United States v. Rose, 215 F. 2d 617 (3rd Cir. 1954); United

States v. Neff, 212 F. 2d 297 (3rd Cir. 1954). The proof in

this case does not exclude the possibility that Slater King

was telling the truth both before the grand jury and the

trial jury. The government’s case is in no way inconsistent

with Slater King’s entirely plausible version of the events

of July 30, 1963.

B. A ppellant Jackson

Appellant Jackson testified before the grand jury that

after receiving her subpoena she did not remember discuss

ing her prospective testimony before the grand jury (R.

332, 338-39); that she did not remember going to the office

of C. B. King on July 30, 1963 (R. 341); that she did not

remember specifically going to the office on any given day

although she may have been in the office from time to time

(R. 344), and that she did not remember seeing Attorney

King’s secretary on July 30, 1963 (R. 345).

The evidence against Mrs. Jackson is particularly weak.

Mrs. Butler testified about the general circumstances of the

gathering (R. 291-93); that Miss Holtzman spoke on the

rights of witnesses appearing before federal grand juries

(R. 2 9 ^ and that Mrs. Jackson was in the office of C. B.

King for 15 to 25 minutes, having arrived between 5 :30 and

6:00 p.m. (R. 294).

Miss Holtzman testified concerning her instructions from

Attorney King (R. 303) and her resulting talk to a number

of persons about the functions and composition of the

grand jury (R. 303-305). She also stated that Mrs. Jackson

22

23

was in the office of C. B. King during part of the time (R.

306).

The only witness who testified directly that Mrs. Jackson

actively participated in the,meeting Avas EdAvard Bryant,

Jr. He stated that in addition to Miss Holtzman, 3 persons,

including Mrs. Jackson, spoke about prospective testimony

before the grand jury (R. 314). Bryant’s testimony, how-

eArer, was thoroughly destroyed on cross-examination.

After Attorney Hollowell confronted Bryant with prior

conflicting testimony about the time when he arrived at____

Attorney King’s office (R. 319-323); and further cross- 7

examination exposing Bryant’s incredibly poor recollection

of events, the folloAving colloquy occurred:

Q. I say you don’t remember anything that was ac

tually talked about at any timet A. No, I don’t.

Q. At that meeting, do you! A. No (R. 330).

It is submitted that neither of the credible witnesses, Mrs.

Butler and Miss Holtzman offered any direct proof that

Mrs. Jackson actively participated in a meeting concerning

testimony before the grand jury to such an extent that Mrs.

Jackson Avould probably haA’e remembered when she Avas

asked about it before the grand jury. Neither testified that

Mrs. Jackson was present during Miss Holtzman’s talk, nor

that Mrs. Jackson engaged in any conversation with anyone

on the subject. Bryant’s testimony must be discarded

entirely. A conviction for perjury requires direct evidence

by two witnesses or direct testimony of one witness cor

roborated by trustworthy testimony of another. Wetter v.

United States, 323 U. S. 606; McWhorter v. United States,

193 F. 2d 982 (5th Cir. 1952). Moreover, proof in perjury

cases must be of a highly convincing nature. Patemostro

v. United States, supra; United States v. Neff, supra. The

24

government’s evidence did not meet these requirements and

the motion for acquittal should have been granted. In the

alternative, it is submitted that the presence in the case of

Bryant’s testimony, extremely incriminating in nature but

totally discredited on cross-examination, was highly preju

dicial to the defendant, and a new trial should be granted.

III.

In the Wells Case the District Court Erroneously Overw

ruled Objections to Testimony that Came Within the

Attorney-Client Privilege.

The indictment against appellant Wells charged him with

having “testified in substance . . . that he did not attend the

meeting held in the office of Attorney C. B. King in Albany,

Georgia, on the afternoon of July 30, 1 9 6 3 and that this

statement was known to be false. At the grand jury hear

ing, however, Rev. Wells was not asked specifically about

the meeting at Attorney King’s office, but rather whether

he had attended a meeting or had participated in a discus

sion with anyone concerning the appearance before the

grand jury (R. 700-705). Thus, in order to connect the

questions as asked with the charge in the indictment, the

government had to prove at trial, first, that Rev. Wells had

gone to Attorney King’s office, second, that he had partici

pated in a meeting or discussion of the grand jury investi

gation while there, and third, that he considered himself as

thus having participated when he answered “no” to the

questions propounded.

That Rev. Wells did go to Attorney King’s office is not

contested, and he never at any time denied that fact. The

main question, therefore, is whether he participated in a

discussion while there. Two government witnesses, Mrs.

Butler and Miss Holtzman, testified as to the subject mat

25

ter of the meeting at Attorney King’s office and Rev. Wells’

participation in it.7 In both instances an objection was

made that the testimony was privileged as relating to con

fidential communications between an attorney (here an at

torney’s agent) and his clients. It is appellant’s contention

that this testimony should have been excluded, and that had

it been the government would have failed to have met its

burden of proving that Rev. Wells had participated in a

discussion of the grand jury. In the alternative appellant

contends that even if there was other evidence that might

support a finding that the meeting was attended, the admis

sion of the privileged testimony, particularly that of Mrs.

Butler, was so prejudicial as to require a new trial.

Mrs. Butler was first asked the subject matter of Miss

Holtzman’s talk to the group assembled in Attorney King’s

office. She answered that it was with reference to witnesses

before the grand jury (R. 641). An objection to this testi

mony was overruled on the ground that the subject matter

of the attorney-client relationship was not privileged

(R. 642). That such is the law is questionable, but since it

is clear from the record that Rev. Wells was not present

at the time the statement was made, and that Mrs. Butler

did not know whether the statement of Miss Holtzman had

been brought to his attention, this evidence does not prove

Rev. Wells’ participation.

Similarly, Miss Holtzman was asked about the subject

matter of her talk, and this question was objected to but

allowed (R. 684-88). Miss Holtzman made it clear that

Rev. Wells was not present when she made her talk

(R. 695), and that she did not remember whether Rev. Wells

7 The testimony of Rev. Wells himself at his trial is inconclusive

on this point. He said that he might have spoken to the people

there about his subpoena, since he had mentioned it to nearly

everyone he met, but his recollection was not clear (R. 760-64).

26

had said anything to the group, or what the substance was

of any remarks he might have made (R. 690, 696). Again,

this testimony only shows that Reverend Wells was at At

torney King’s office; it fails to prove the crucial link, viz.,

that he participated in a discussion concerning the grand

jury.

The one piece of testimony that clearly said that Rev.

Wells did talk about the grand jury hearing was given by

Mrs. Butler. She was asked whether Rev. Wells talked to

the group in Attorney King’s inner office. She said that he

did say something to the people that were sitting near him,

but not to the entire group. The government then asked

what he was saying:

A. Now, as to what he was saying, I really couldn’t

say. I believe—No—he explained the conditions under

which he felt that he had received his subpoena (R. 655-

56).

The question and answer were objected to, again on the

ground of attorney-client privilege, but the court overruled

the objection and allowed the witness to continue telling

what Rev. Wells had said (R. 656-660).

The attorney-client privilege extends not only to com

munications to the attorney himself, but to his agents, par

ticularly his law clerks and secretaries. 8 Wigmore $2301

(McNaughton rev. 1961). Thus, any communications to

Mrs. Butler and Miss Holtzman would ordinarily be privi

leged.

In most cases, however, the privilege is destroyed if

third persons are present when the communication is made,

since it is not then confidential. An exception to the rule

is generally recognized when the other persons are also

clients or other persons with an interest in the matter

27

under discussion. As to third persons, the communication

made by them in the course of a conference with the attor

ney (or his agent) do come within the scope of the privi

lege. Baldwin v. Comm’r of' Internal Revenue, 125 F. 2d

812 (9th Cir. 1942); see also Anno. 141 A. L. R. 548, 564-

State v. Archuleta, 29 N. M. 25. 217 Pac. 619 (1923); State

v. Emmanuel, 42 Wash. 2d 799, 259 P. 2d 845, 854-55 (1953).

Applying these rules to the facts in the present case, the

following appears. The meeting in Attorney King’s office

was for the purpose of giving those in attendance advice,

hrough Mr. King’s agent, concerning their rights and du

ties before the grand jury. Although it is not clear just

who was in attendance when Reverend Wells was there, all

m the inner office at that time were apparently clients of

Mr. King or persons directly interested in the subject mat

ter under discussion. Mrs. Butler testified that what was

said could not be heard in the outer office (R. 644, 648)

and she indicated that she was in the inner office when she

did hear the remarks testified to (R. 657). Hence, there is

no evidence that anyone in the outer office, i.e., third per

sons not concerned with the grand jury discussion, over

heard what was said. Wells therefore made the statements

during the course of a conference between clients and other

interested persons and the attorney’s agents.

The fact that Reverend Wells apparently addressed at

least some of his Pemedm^to some of his fellow clients and

notnecessanly to the agent, would not seem to put them

outside the privilege. The policy of the attorney-client

privilege is to encourage free discussion and disclosure

between attorney and client so that the former will be fully

apprised of all the facts and circumstances of the case

Schwimmer v. United States, 232 F. 2d 855 (8th Cir. 1956)’

Where a number of clients are involved, the same policy

should apply and allow them to confer among themselves

28

and their attorney. To raise the fear of forced disclosure

of any remarks addressed to fellow clients would be to

introduce a technicality that would only serve to stifle the

freedom of discussion necessary for the obtaining of legal

advice and the resulting furtherance of justice.

For these reasons, appellant urges that the failure to ex

clude the testimony was error, and either that its proper

exclusion would have meant that there was not sufficient

evidence to connect his presence in Attorney King’s office

with his knowingly having attended a meeting in which the

grand jury appearance was discussed, or, in the alternative,

that its inclusion was prejudicial and necessitates a new

trial.

CONCLUSION

F ob the foregoing seasons the judgments below should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Gbeenberg

Constance B aker Motley

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

D onald L. H ollowell

859y2 Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

C. B. K ing

211 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

D orothy K enyon

F rank H. H effron

Of Counsel

29

Certificate of Service

T his is to certify that I have served a copy of the fore

going Brief for Appellants upbn Floyd M. Buford, Esq.,

United States Attorney and Wilbur D. Owens, Jr., Esq.,

Assistant United States Attorney, Macon, Georgia, Attor

neys for Appellee, by mailing copies to them at the above

address, air mail, postage prepaid.

T h is.......... day of November, 1964.

Attorney for Appellants

17a

a p p e n d ix b

(

*{> ,/ i

< " >

County

Baldwin

Bibb

Bleckley

Butts

. Crawford

Hancock

Houston

Jasper

Jones

Lamar

Monroe

Peach

Pulaski

Putnam

Twiggs

Upson

Washington

Wilkinson

Totals

Federal Jury List— Macon Division 1959

s o n X

ist< Neg

Persons

Jury List(f Negroes

from County on List

137

666

- 72

58

47

64

99

57

67

84

70

123

58 '

61

37

130

95

60

1985

8

36

2

2

5

3

7

4

5

7

5

8

3

4

1

6

6

5

117

Negro

Percentage

on List

Adult

Population

1960

Adult

Negro

Population

1960

5.8% 2368 8744

5.4% 81133 24894

2.7% 5230 1246

3.4% 4920 1878

10.6% 2948 1435

4.6% 4877 3237

6.0% . 20438 3815

7.0% 3404 1554

7.4% 4490 1983

8.3% 5708 1925

7.1% 5605 2392

6.5% 7398 3913

5.0% •>> 4546 1697

6.5% 3822 1988

2.7% 4189 1997

4.6% 13835 3315

6.6% 10041 4925

8.3% 5054 2076

5.8% 211306 73014

Population figures based on 1960 United States Census,

ury figures based on affidavits (App. 10a-16a).

Negro

Percentage

of Adult

Populatidh

1960

36.9

30.5

23.8

38.1

48.6 -11

66.3

18.6

45.6 ;

44/' '*> -

33.7

42.6 &

52.8

37.3 '•

52 /

47.6 ■

23.8

49. >

41. ' •'

34.55%

I