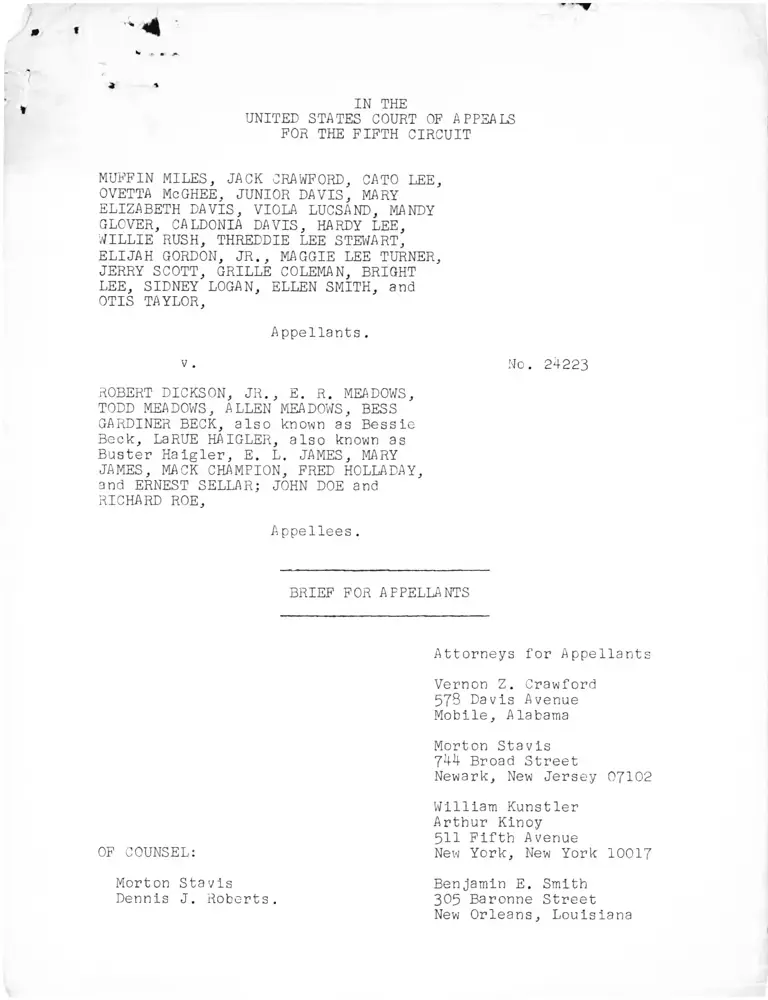

Miles v. Dickson Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 31, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Miles v. Dickson Brief for Appellants, 1967. 17eb19a0-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9b24374b-212e-4a56-9231-70da31699e94/miles-v-dickson-brief-for-appellants. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MUFFIN MILES, JACK CRAWFORD, CATO LEE,

OVETTA McGHEE, JUNIOR DAVIS, MARY

ELIZABETH DAVIS, VIOLA LUCSAND, MANDY

GLOVER, CALDONIA DAVIS, HARDY LEE,

WILLIE RUSH, THREDDIE LEE STEWART,

ELIJAH GORDON, JR., MAGGIE LEE TURNER,

JERRY SCOTT, GRILLE COLEMAN, BRIGHT

LEE, SIDNEY LOGAN, ELLEN SMITH, and

OTIS TAYLOR,

ROBERT DICKSON, JR., E. R. MEADOWS,

TODD MEADOWS, ALLEN MEADOWS, BESS

GARDINER BECK, also known as Bessie

Beck, La RUE HAIGLER, also known as

Buster Haigler, E. L. JAMES, MARY

JAMES, MACK CHAMPION, FRED HOLLADAY,

and ERNEST SELLAR; JOHN DOE and

RICHARD ROE,

A ppellants.

v . No. 24223

A ppellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Attorneys for Appellants

Vernon Z. Crawford

578 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama

Morton Stavis

7^4 Broad Street

Newark, New Jersey 07102

OF COUNSEL:

William Kunstler

Arthur Kinoy

511 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10017

Morton Stavis

Dennis J. Roberts.

Benjamin E. Smith

305 Baronne Street

New Orleans, Louisiana

Citations j_v

Statement of the Case 1

Specification of Errors 6

Argument 7

I. THE MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT WAS ERRONEOUSLY

GRANTED AS THE DEFENDANTS FAILED TO DEMONSTRATE

THE ABSENCE OF GENUINE ISSUES OF FACT. 7

A. The Legal Reguirements for Summary Judgment 7

B. Analysis of the Depositions. 12

1. The Plaintiff Threddie Lee Stewart

and the Defendant E. L. James and

LaRue "Buster" Haigler. 14

2. The Plaintiff Cato Lee and the

Defendant LaRue "Buster" Haigler. 19

3. The Plaintiff Muffin Miles and the

Defendant Bess Gardiner Beck. 23

3. The Plaintiffs Elijah Gordon and

Grille Coleman and the Defendant

Mack Champion. 26

5. The Flaintiff Ellen Smith and the

Defendant Todd Meadows. 27

6 . The Plaintiff Jack Crawford and

the Defendant Robert Dickson. 23

7. The Plaintiff Sidney Logan and

the Defendant Fred Holladay. 28

C. The Interconnection of the Defendants. 29

D. The Atmosphere at the Deposition Taking

did not Afford the Trier of Facts the

Opportunity for Evaluation of Either the

Conflicts of Testimony or the Unreliability

of the Defense Testimony. 33

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

i i

*

E. The Standard for the Evaluation of

the Deposition Testimony.

Page

37

II. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN IMPOSING COSTS

AGAINST ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS. 39

A . The Court Below had no Basis in Fact

for Assessing the Costs herein Against

the Attorneys. 4o

B. The Court Below had no Basis in Law

for Assessing the Costs herein. 48

C. To Assess Costs Against the Attorneys

Without a Hearing and Without Opportunity

to Clarify the Situation was a Violation

of Due Process of the Law. 52

D. The Assessment of Cost Against the Attorneys

was contrary to the First and Sixth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United

States. 56

CONCLUSION 59

i i i

CITATIONS

Cases Page

Adkins v. DuPont Co.,

335 U.S. 331 (1948) .................................. 59

Bardin v. Mondon,

2W " F . 2d 235 (2d Cir., 19 6 1) ......................... 51

Braun v. Hassenskin Steel Co.,

23 F.R.D.' i'63 (D.S.D., 1959) ......................... 48,52

Brookins v. State,

221 Ga. 181, 144 S.E.2d 83 (1965) ................... 38

Brown v. Allen,

34T U.S7 44'6 (1953) .................................. 38

Colby v. Klune,

178' F .2d 872 (2d Cir., 1949) ......................... 11

Coyne & Delany Co. v. G. W. Onthank Co.,

(s .d . iowa, 1950) 10 f .r .d . 435 rrrr................. .5 1

Elgin J. & E. Ry. Co. v. Burley,

325 U.S. 711 on reb. 327 U.S. 66l (1945) ............ 7

Farmer v. Arabian American Oil Co.,

379 U.S.''22.7(1964) ................................... 57

Gamble v. Pope & Talbot, Inc.,

307 F.2d “729 (3d Cir., 1962) ......................... 53,55,56

Gold Dust Corp. v. Hoffenberg,

87 F.2d 451" (2d Cir., 19 3 7) .......................... 49

Hamm v. Rock Hill,

379 U.S. 306' (1964) .................................. 38

Holt v. Virginia,

381 u.s.' 131 (1965) .................................. 58

In re Jess Brown,

346 F . 2d 903 (5th Cir., 1965) ........................ 58

In re Childs Co.,

'52 F. Supp. 89 (S.D. N.Y., 1943) .................... 48

In re McConnell,

370 U.S. 230 (1962) .................................. 59

iv

Page

Lefton v. Hattiesburg,

333 F .2d" 280 (5th Cir., 1964) ......................... 58

Lombard v. Louisiana,

373 U.S. 267 (1963) .................................... 38

Loudermilk v. Fidelity & Casualty Company of New York,

199 F • 2d 561 (5th Cir., 1952) ................ ....8,9,10,12

Masterson v. Pergament,

203 F .2d 315 (6th Cir., 1953) ......................... 42

Morrissette v. United States,

342 U.S. 246 (1951) .... ............................... 39

Motion _Pi_cture Patents Co. v. Steiner,

201 F. 63 (2d Cir., 1912) ............................. 50,51

NAACP v. Button,

371 U.S. 415 (1963) .................................... 58

Nix v. Dukes,

58 Tex'. 98 (1882) ...................................... 43

Peterson V. Greenville,

373 U.S. 244 (1963) .................................... 37,38

Poller v. Columbia Broadcasting System,

; 368 u . s . 464 (1962) 77.7........ 7 ........................................... 8 , 9 , 1 0 , 3 3

Robinson v. Florida,

378 U.S. 153 (1964) .................................... 38

Sartor v. Arkansas Natural Gas Corp.,

321 u . s . '620 (1944) 7777777777777...................... 7

Shields v. Midtown Bowling Lanes,

11 Race Rel7 L. Rep. 1492 (M.D. Ga., 1966) ........... 38

Sioux County v. National Surety Co.,

275 u . s . 238 (1928) 777777777.......................... 48

Sonnentbeil v. Christian Moerlein Brewing Co.,

172 U.S. 401 (1899) 7.................................. 11,3 0

State ex rel. Milwaukee v. Ludwig,

106 Wise. 226, 82 N.W. 158 (1900) .................... 43

C ase s ( C o n t ' d )

v

Stevenson v. United States,

162 U.S. 313 "(1896) 777............................. 39

Toledo Metal Wheel Co. v . Foyer Bros. & Co.,

”“223 f . 350 (bth cir., 19 15) 77777777777.......... 50,5 1,53,54

United States v. Diebold, Inc.,

329 u . s . 654 (19627 7777777........................ 7

United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole,

"263 F .2d 7l (5th Cir., 1959) cert, denied 372 U.S.

915 (1963) ................. 7777.................. 57

United States v. Harvey,

“ 250 F. Supp. 219 (E.D. La., 1966) ................ 38

United States ex rel. Payne v. Call,

287 Fed7 520 (5th Cir., 1923) .................... 48

United States ex rel. Seals v. V/iman,

304 F.2d 53 (5th Cir., 1962) ...................... 57

Weiss v. United States,

227 F .2d 72 (2d Cir., 1955) cert, denied 350 U.S.

936 (1956) ................ 77777.777.77........... 52

White Motor Co. v. United States,

372 u . s . 253 (1963! 7777777777.................... 8,9,10

Whitten v. Dabney,

171"_Co 1 o."621, 154 P. 321 ......................... 43

Constitution, Statutes and Rules

Constitution:

First Amendment ................................. 6,56

Fifth Amendment ................................. 53

Sixth Amendment ................................. 6,56

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1927 ................................ 49,50,51,

53,54

Cases ( C o n t ' d ) Page

v i

Rules:

Rule 23(c), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure .... 42,47

Rule 54(d), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure .... 49

Rule 56(c), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure .... '7 40

Miscellaneous

2 Barron & Holtzoff, Federal Practice and Procedure

§ 570, (Rules ed. 19 6 1) ......................... 43

Book Review: Southern Justice,

54 Calif. L. Rev. 303 (1966) .................... 46

Canons of Professional Ethics, Canon 9

American Bar Association, p .8 (1957 ed. ) ....... 47

Commission on Civil Rights Report, Voting,

(19 6 1) p. 26 35

6 Moore's Federal Pracitce (Spec. Supp. p. 11

preceeding p. 2001) .............................. 7

Morgan, "Segregated Justice", Southern Justice,

155 (Friedman ed . 1965)............................ 46

New York Times (March 14, 19 6 7) p. 35 ............ 2

Note: 17 Corn. L. Q. 140 (1931) .................... 43

Note: 50 111. Bar J. 800 (1962) .................... 56

Stephen, 2 History of the Criminal Law III ........... 39

/ *

Page

v i i

i

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On January 10, 1966, a class action complaint was filed

in the United States District Court for the Middle District of

Alabama by the plaintiffs seeking an injunction against the de

fendants, individually and collectively, and all person acting

in concert with them and all other landowners in Lowndes County,

Alabama, enjoining said defendants, and others as indicated, from

threatening, intimidating or coercing in any manner, economic or

otherwise, for the purpose of interfering with the right of

plaintiffs, or of any other person, to become registered to vote,

and penalizing or punishing any person by economic sanctions, or

otherwise, for having registered to vote or attempting to do so.

More specifically, plaintiffs asked the Cburt below to enjoin the

named defendants, extensive landowners, from evicting or termi

nating the tenancy or sharecropping arrangements of the plaintiffs,

or any other Negroes in Lowndes County, Alabama, by reason of

their registering to vote, and, further, to enjoin the defendants

from preventing the plaintiffs, or other Negroes, from returning

to their former homes and resuming their tenancies or former

sharecropping arrangements.

The background is familiar to anyone acquainted with the

rural counties of the deep South. Lowndes County, as of 1964,

had not a single Negro registered to vote. It is situated between

Selma and Montgomery and figured prominently in the famous march

- 1 -

between those two cities in 1964— Mrs. Liuzzo was_ murdered

* /

there.Encouraged by the passage of the Voting Rights Act of

1965, the Negro community began a large voter registration drive.

This case deals with the response of the white community

to that registration program.

The complaint alleged, in part:

"In an effort to prevent continued registra

tion of Negroes and the consequent vesting of

majority power in the Negro people, the defendant

landowners entered into a conspiracy with numerous

persons presently to the plaintiffs unknown, to

intimidate, threaten, and coerce the Negro citi

zens of Lowndes County by evicting them or

threatening to evict them from their homes and

lands, denying them credit, denying them an oppor

tunity to continue sharecropping or tenant farming

arrangements, and otherwise denying them their

livelihoods and imposing economic sanctions on

them by reason of their registration to vote and

the impending exercise of their right of franchise."

To avoid unnecessary repetition we would respectfully

refer this Court to pp. 14-29 of this Brief where we set out the

basic facts by presenting the circumstances regarding several of

the plaintiffs. We have set out this material because it is

typical and amply illustrative of the facts. These case histories

reduce themselves to the following: A state of affairs of remark

able stability,persons living on their premises under various

l/ That peace has not yet come to Lowndes County is evidenced

by a New York Times article of March 14, 1967, p. 35, describ

ing the burning of both a Negro church and the office of the

Lowndes County Movement for Human Rights, Inc., the local

anti-poverty organization, within 24 hours.

- 2 -

sharecropping and tenancy arrangements for decades and even

generations--is suddenly disturbed throughout the County. There

is only one fact which has occurred which explains the dramatic

turn of events, and that is that the Negroes are asserting their

right to a franchise; and this is not left to pure inference, be

cause in case after case comments and remarks were made by various

defendants or their agents which left no doubt as to the reasons

for the action and the motives and purposes of the defendants.

Moreover, the intimate relations which exist among the

several defendants indicate that the program under way does not

represent the individual actions of separate landlords. The con

currence in point of time of all these actions taken by the

several landlords, in the light of testimony establishing their

close business and social relations, leaves more than an inference

that the evictions were the result of a general understanding

among the defendants.

The prayer for relief sought that an injunction issue

against the defendants enjoining them from threatening, intimi

dating, or coercing in any manner, economic or otherwise, for the

purpose of interfering with the right of any person to become

registered to vote, or penalizing or punishing any person, whether

by economic sanctions or otherwise, for having registered to vote

or attempted so to register, and specifically enjoining the said

defendants from evicting or terminating the tenancy or share-

cropping arrangements of the plaintiffs or any other Negroes by

-3-

reason of their registering to vote, and if they have prior to

the date of any injunctive order of this Court already effected

such eviction or termination, then enjoing them from preventing

the said plaintiffs or other Negroes from returning to their

homes and resuming their tenancy or sharecropping arrangements.

It further sought appointment of United States Commissioners to

protect the lawful franchise activities of citizens of Lowndes

County.

Both plaintiffs and defendants served notice for taking

the pre-trial depositions of opposing parties and these deposi

tions were taken over a period of several days in February, 1966.

On March 10, 1966 the Court below entered an Order that all pre

trial discovery be completed by March 25 and that all parties

file summaries of any depositions taken at their instance. On

March 21 and April 8 further Orders were filed extending the

time for filing, and between April 15 and May 28 all of the

summaries and supplements to summaries of depositions had been

filed. During this time defendants had filed motions for sum

mary judgment, accompanied by the depositions and affidavits,

and on May 26 the Court below set the motions for submissions on

written briefs.

On June 15 the Court below entered its order and judgment

on defendants' motions for summary judgment and stated:

"Upon consideration of these several

motions, the pleadings, requests for

admissions and responses thereto,

- 4-

affidavits, approximately forty depositions and the summarizatlons thereof,

and the briefs of the parties, this

Court concludes that there is no genuine

issue between these plaintiffs and the

defendants as to any material fact and

that each of the defendants as above

named is entitled to a judgment as a

matter of law."

Futhermore, the Court below found that "justice requires the

taxation of the costs against the attorneys who filed the case,"

and taxed said cost, amounting to One Thousand Five Hundred

Forty and 80/100 Dollars ($15^0.80), against the attorneys of

record for the plaintiffs.

On July 1 plaintiffs filed a motion for reargument of

the motion for summary judgment and to vacate the order of June

15. Said motion was denied on July 5* and on July 11, 1966,

plaintiffs filed their notice of appeal to this Court.

It is important to note that at no time was an oral

hearing on the motion for summary judgment ever held. The judg

ment of the Court below was based solely on the briefs, deposi

tions and papers filed with it. The Court never had an oppor

tunity to make an evaluation of the credibility of the deponents

upon observation of their manner. That observation of the

deponents to evaluate their credibility before granting the

motion for summary judgment was vitally important in this case

is made clear from the detailed summary of the conflicting testi

mony set out below. It is sufficient to state here that there

was a vast amount of testimony showing disparity and contradic

tions not only as between plaintiffs and defendants, but between

- 5-

the various defendants.

Furthermore, the taxation of costs against the attorneys

for plaintiffs was not done by way of any motion, nor were

counsel ever afforded any notice that the Court was even con

sidering such a unique step. Denied any opportunity to offer a

showing of the true facts, attorneys for the plaintiffs first

knowledge of any question of costs came in the final order and

judgment of the Court below. This most unusual and clearly

invalid assessment was done without any opportunity being afforded

by the Court below for the attorneys to be heard in argument or

present testimony on the issue.

SPECIFICATION OF ERRORS

1) The Court below erred in granting defendants’

motion for summary judgment as there was a failure

to demonstrate the absence of genuine issues of fact.

2) The Court below erred in assessing costg against

attorneys for the plaintiffs for the following

reasons:

a. ) There was no basis in fact or in

law for this action.

b. ) Said action was a violation of the

Due Process Clause.

c. ) Said action was contrary to the First

- 6 -

and Sixth Amendments of the United

States Constitution.

ARGUMENT

I

THE MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT WAS

ERRONEOUSLY GRANTED AS THE DEFENDANTS

FAILED TO DEMONSTRATE THE ABSENCE OF

GENUINE ISSUES OF FACT.

A . The Legal Requirements for

Summary 'Judgment

It was defendants burden., on their motions for summary

judgment, to "show that there is no genuine issue as to any

material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment

as a matter of law." Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule

56(c); Sartor v. Arkansas Natural Gas Corp., 321 U.S. 620, 64

S.Ct. 724, 88 L.ed. 967 (1944); Elgin J & E Ry, Co. v. Burley,

325 U.S. 711, 65 S. Ct. 1282, 89 L.ed. 1886; on reh. 327 U.S.

661, 66 S. Ct. 721, 90 L.ed. 928 (1945); United States v.

Diebold, Inc.. 329 U.S. 654, 82 S. Ct. 993, 8 L.ed. 2d 176 (1962).

The recent amendments to Rule 56 have not altered the

above standard governing motions for summary judgment. Advisory

Committee Note to Rule 56(c), 6 Moore’s Federal Practice Special

Supp. p. 11 preceding p. 2001:

."Nor is the amendment designed to affect

- 7-

the ordinary standard applicable to the

summary judgment motion. So, for example:

Where one issue as to a material fact can

not be resolved without observation of the

demeanor of witnesses in order to evaluate

their credibility, summary judgment is not

appropriate. Where the evidentiary matter

in support of the motion does not establish

the absence of a genuine issue, summary

judgment must be denied even if no opposing

evidentiary matter is presented. .

In support of their motion, defendants submitted affi

davits solemnly denying any malicious motive of interfering with

plaintiffs' civil rights in connection with their undisputed

actions whereby plaintiffs were excluded from defendants' lands.

The Court below acknowledged that in cases where motive and in

tent are crucial elements, a court should procede with caution

in granting motions for summary judgment. However, it sought

to avoid the rule laid down in Poller v. Columbia Broadcasting

System, 368 U.S. 464 (1962), that "summary procedures should be

used sparingly ... where motive and intent play leading roles,

the proof is largely in the hands of the alleged conspirators,

and hostile witnesses thicken the plot," at 473, by stating that

"since the plaintiffs have not been deprived of their opportunity

to cross-examine any of the defendants, the reasons for not

granting the motions for summary judgment that existed in Poller

v. Columbia Broadcasting System, 368 U.S. 464 (1962); White

Motor Company v. United States. 372 U.S. 253 (1963); and Louder-

milk v. Fidelity & Casualty Company of New York, 199 F. 2d 561

(5th Cir. 1952), are not controlling in this case." Opinion, p.4.

- 8 -

However* this result can only be arrived at by a mis

reading of Poller and the other cases cited. The Court seems to

be distinguishing the cases based on the assumption that in the

case at hand plaintiffs had the opportunity to depose the op

posing parties* while in Poller only affidavits were before the

court which granted the summary judgment. A close reading of

the Court's opinion in Poller reveals that the affidavits "were

supplemented by material taken from petitioner's depositions of

Salant and CBS President Stanton"* at 468* and this fact is

highlighted in the dissent of Mr. Justice Harlan where he stated:

"In passing on the motion for summary

judgment* the District Court had before

it more than the four affidavits of interested

parties to which the Court's opinion seems

especially to refer. In the record was the

testimony of four key witnesses taken by pre

trial depositions. Petitioner's counsel had

examined Frank Stanton* President of CBS;

Richard Salant* a Vice President of CBS; and

Thad Holt* who acted for CBS in procuring the

option on the Bartell station. Petitioner's

testimony was also in the record in the form

of a deposition taken by respondents' counsel*

and two affidavits submitted in Apposition to

the motion for summary judgment." at 477.

Likewise* neither White Motor Co.*supra* nor Loudermilk.

s_u£ra_, were cases which can be distinguished away upon any con

tention that the party opposing the motion for summary judgment

did not have the opportunity to cross-examine. In White Motor

a summary judgment was granted on the admissions of the party

opposing the motion because the Court felt that there was a per

se violation of the statute involved. The granting of the summary

judgment was reversed not because of a denial of an opportunity

to cross-examine but because the complexity of the issue at hand

- 9-

required a full scale hearing. Furthermore, the dissent of

Mr. Chief Justice Warren notes, at 275-6, that there was a "...

deposition of the secretary of White Motor ...", so there was an

opportunity to cross-examine.

Finally, Loudermllk v. Fidelity & Casualty Co. of New

York, 195 F.2d 561 (5th Cir. 1952) is also a case where the

parties had an opportunity to cross-examine, and nevertheless

summary judgment was denied. There a motion for new was

granted to the defendant following a trial in which the issues

were fully litigated before the court below. The plaintiff then

moved for summary judgment "based on the pleadings and the

transcript of the record made on the trial before the district

judge , at 564. The Court below granted the motion for summary

judgment based on testimony taken at the trial and the Court of

Appeals reversed based on this evidence. Thus, the case cer

tainly does not stand for the proposition that summary judgment

was denied because of a lack of opportunity to cross-examine.

Therefore, the reason of the Court below that distinguishes

the case at hand, that is, that here "the plaintiffs have not

been deprived of their opportunity to cross-examine any of the

defendants", must fall.

The Court in Poller stated at 473: "It is only when the

witnesses are present and subject to cross-examination that their

credibility and the weight to be given their testimony can be

appraised." In light of the fact that opposing counsel In Poller

- 1 0 -

did have the opportunity to cross-examine on depositions, the

Court could only be concerning itself with the cross-examination

of parties before the trier of fact, so that their credibility,

as evidenced by their demeanor in testifying, could be weighed

and appraised.

Where "motive and intent" are crucial elements, the issue

of credibility is inevitably at stake. Thus, plaintiffs may not

be deprived of their opportunity to cross-examine defendants and

their witnesses and to have the <Sourt assess their demeanor upon

final hearing. Sartor v. Arkansas Natural Gas Corp., supra;

Sonnentheil v. Christian Moerlein Brewing Co.. 172 U.S. 401, 408,

19 S. Ct. 233, 43 L.ed. 492 (1899)* In an applicable statement

quoted and followed in Sartor, the Supreme Court had pointed out:

"... the mere fact that the witness

is interested in the result of the suit

Is deemed sufficient to require the credi

bility of his testimony to be submitted

to the jury as a question of fact."

Sonnentheil v. Christian Moerlein Brewing

Co., supra, l72'“tJ.S. at 408. ~

This important principle of trial court observance of

demeanor to appraise credibility in these situations has been

enunciated on many occasions. The court in Colby v. Klune, 178

F.2d 872, 875 (2nd Cir. 1949) stated that, "Particularly where,

as here, the facts are peculiarly within the knowledge of defen

dants or their witnesses, should the plaintiffs have the oppor

tunity to impeach them at a trial; and their demeanor may be the

most effective impeachment. Indeed, it has been said that a

- 1 1 -

witness1 demeanor is a kind of ’real evidence1; obviously such

'real evidence' cannot be included in affidavits."

In Loudermllk, supra, at 565-566, this Circuit has said:

"This is peculiarly the kind of case

where the triers of fact, whose business

it is not only to hear what men say but

to search for and find the roots from

which the sayings spring, should be af

forded full opportunity to determine the

truth and integrity of the case."

B. Analysis of the Depositions.

All throughout the depositions of the defendants are

statements which would lead a trier of fact to conclude that the

entire truth was being withheld. Unfortunately, it was not

feasible to summarize all of the testimony, a picture of the de

meanor of the witnesses, or the impression created by their

general comportment. Not only were the witnesses withholding

the truth, but their manner was flippant, arrogant and intransi

gent. This come through slightly in the depositions, if one

reads them from cover to cover. It is impossible to convey it

in a summary. However, a trier of fact, confronted with such

a performance by the defendants would, without question, reject

the glib motives the defendants claim in their affidavits as pure

fabrications, which they patently are.

There were substantial conflicts and omissions within the

testimony of the defendants, and many major conflicts between

the testimony of the defendants and the plaintiffs. A thorough

reading of the depositions shows that the substantial questions

1 2 -

of fact, of a nature to only be resolved at the trial of the

cause, existed. A full hearing before the court would neces

sarily be the only means for assuring an ascertainment of the

truth.

Basically, plaintiffs contended that in the late summer

and fall of 1965 a significant number of Negroes who had regis

tered or attempted to register, or whose wives had registered,

or who had engaged in civil rights activities or whose wives or

families had done so, were suddenly deprived of their means of

livelihood by the defendants. Financial arrangements which had

been in effect with various plaintiffs for decades were suddenly

terminated. Sharecroppers or tenant farmers were notified that

they would have to give up the land and/or the houses they rented

by the end of the year. One plaintiff was advised that he would

not receive financing for the ensuing year; another plaintiff

was deprived of hauling work which he had performed for years; a

third plaintiff was required to pay off a mortgage which had been

standing for three years. The pattern was clear. Pursuant to

an obvious design, the defendants almost simultaneously "put the

squeeze" on the Negroes, with the obvious purpose of discouraging

the rest of the Negro population from exercising their civil

rights. A brief synopsis of some of the depositions will amply

demonstrate the unlawful scheme of the defendants, and make these

conflicts apparent.

- 13-

1. The Plaintiff Threddie Lee Stewart and the

Defendants E.L. James and LaRue "Buster11 Haigler.

Plaintiff Threddie Lee Stewart has lived on and farmed

the land of defendant E. L. James ever since 1946. ( 3 ^ ) -/ Each

year since 1951 "Buster" Haigler has been advancing him money

to farm (13). During these many years Haigler had never spoken

to him about paying the entire debt off (1 9 ).

In March, 1965, Stewart attempted to register with the

County officials (164). No one was allowed to register and a

list was made by the County officials of all those who presented

themselves that day (16 9). Haigler knew of the existence of the

list of those who attempted to register, but he denied seeing

it (Haigler, Deps.,55). Two days after he attempted to

register (16 9) Stewart saw Haigler about getting a loan. At

that time Haigler questioned him extensively about Negro voter

registration in the county, (98, 154) and said "I thought you

were with that riot crowd" referring to Dr. Martin Luther King (98).

t y Numbers in parentheses refer to page number of deposition

of T-hraddie- Lee Stewart,, unless .otherwise designated.

across theHaigler further told him that he would be "put ...

fence from the white people" (109), that anyone who takes any

part of the Civil Rights Act would be "crossed up with the white

folks" (109), and that if Negroes take part in voter registra

tion activities "it is going to bring difficulties there" (155).

Instead of loaning him the money Haigler told him that he would

first "talk to Mr. James on that" (98), although this had never

been his practice in prior years . (170).

Two days after Stewart’s meeting with Haigler about the

advancement Mr. James came to Stewart’s house (156). James

questioned him in a threatening manner regarding civil rights

activities and made inquiry as to whether Stewart was planning

to move to Atlanta (the seat of Dr. King’s civil rights activi

ties) (42,43,156). He further indicated that Haigler called him

and told James about Stewart’s attempting to register (43,99)

and that James "wanted to know which way you were going" (99).

In July, 1965, Stewart enrolled his daughter in the white

school (107). Haigler sent for him, interrogated him at length

concerning her application, asked him if anyone told him to en

roll his child (ill), told him to withdraw his child's name, and

implied that he might be put off James' land (ill).

Stewart made at least two subsequent attempts to register

to vote (105,l6l) in July and August. His wife registered in

July (106). Haigler again sent for him and on October 19, 1965

told Stewart that he would have to pay off his debt in full (14,

15).

- 15-

On November 24, 1965, James came to Stewart’s bouse and

told Stewart that Haigler said "that be couldn’t carry you any

longer" (30), that James would not give him any cotton acreage

for the following year (3 1 ), and that be would have to be off

the land by January 1, 1966 (32). The James family even refused

to allow him to rent his bouse for the coming year (3 7).

Stewart was on the Executive Board of the Lowndes County

Christian Movement (the local civil rights organization) (16 7)

and worked actively to encourage Negroes to register and vote

(16 7, 177, 179, 180). He did not know of any other tenants on

the James land that worked to get others registered (176-179).

From the entire testimony of plaintiff Stewart it seems

reasonably inferrable that Haigler, acting in concert with James,

arranged to have him evicted from the land for his voter regis

tration activity.

Defendant E.L. James testified to the following:

"I informed Threddie that Mr. Haigler

had informed me that he was no longer going

to advance Threddie, and in that case

Threddie would have to move, because neither

my mother nor her— the other heirs of the

place, I didn’t use the words heirs to him,

had not done any advancing and could not,

and at that time he asked me if he could re

move two doors from the house that he was

living in, as they were special doors that

he had put in himself— and if he could take

down a fence that he had put up on the farm,

to farm a small pasture for cows around his

house, the livestock around his house. I

informed him that he could. That was about

all of the conversation." (James, Deps. 13).

- 1 6 -

James admitted that he was aware of Stewart's regis

tration attempts and assumed that Haigler was also aware of that

fact (James, Deps. 19). James stated, in reference to the

attempts of Negroes to register, "It was common knowledge. Every

one was discussing it to a certain extent." (James, Deps. 24).

He felt certain that the matter of Negro registration must have

come up in some of his conversations with Haigler as they see each

other quite often, socially as well as in business (James, Deps.

25). Aside from his friendship with Haigler, other mutual friends

were Robert Dickson, E.R. Meadows, and Todd Meadows ( James,

Deps. 26) and he said it was a good possibility that the regis

tration drive in Lowndes County was discussed with that group.

(James, Deps. 26-27).

James further testified that he received word from

Haigler "that he wanted to talk to me about Threddie Lee Stewart,

in view of all the attempts to register, whether he would be

working the land next year or not in 1966" (James, Deps. 6 7).

In light of James' admissions regarding Haigler's concern

with Stewart's voter registration activities, it is interesting

to note Haigler's testimony on this subject. When Haigler was

deposed he stated that he has been cutting back his loan business

because of his family's request that he do so, and because a lot

of land was going into cattle (Haigler, Deps. 26-27). It Is

strange that he would single out Stewart to cut down on his loan

business as Stewart was only advanced on 12 acres, a small

- 17-

proportion of the operation (James, Deps. 6 5), and that he

continued advancing to the four other tenants on the James

property (James, Deps. 48-49). However, subsequent testimony

of Haigler revealed that of the 48 people he named as those to

whom he was no longer loaning money (Haigler, Deps. 34-41,44,46,

81-83), only three were discontinued at his insistence for being

"mighty sullen" or "trashy" (Haigler, Deps. 34,35.*46). All of

the rest either quit or moved on their own accord. In the deposi

tion he specifically denied cutting off Stewart, "I didn't cut

off any of them", and listed him among those who had "died, moved,

or cut off themselves" (Haigler, Deps. 83). Haigler's deposition,

taken on February 9, 19^6, was in direct contradiction to the

testimony of his fellow defendant James. However, on May 31,

1966, Haigler gave an affidavit in support of the motion for

summary judgment. At this time his recollection of the termi

nation of Stewart is completely different from his testimony at

the deposition taking. He said in his affidavit:

"I did not continue advancing Threddie

Lee Stewart in 1966 due to the fact that

he was a poor credit risk and as a matter

of fact, he had never paid up his account

at the end of any farming season. He was

always in arrears and had never brought

his account up to date. He would not

attend his farming operation as he should."

It is interesting to note that it took Haigler 15 years

to decide that Stewart was a poor credit risk; he had been ad

vancing him funds since 1951. Still more interesting is his

observation that Stewart "would not attend to his farming

- 18-

operation as he should." All through the depositions of Haigler,

James, and Stewart, there is not one iota of criticism of

Stewart's operation of his farm. He had been working this same

land since 1946. There is also no testimony that he had changed

his farming operation in any way from previous years. The only

difference in behavior which appears in the record is that beginn

ing in March 1965 , Stewart became active in the civil rights move

ment in Lowndes County, began attending civil rights meetings,

became an executive board member of the movement, attempted to

register to vote, and actively encouraged other Negroes in the

County to register. But perhaps this activity is exactly what

Haigler has reference to when he says that "he would not attend

to his farming operation as he should".

Although Haigler initially denied that he had refused

to advance funds to Stewart for the next season and was demanding

a full accounting, his subsequent admission of that fact poses

a very clear question of fact. Stewart was cut off from his

livelihood by defendants Haigler and James. Was the reason

because of his voter registration activity or because, as an

afterthought, he "was a poor credit risk"? This question of fact

cannot be resolved by depositions and self-serving affidavits,

but can only be resolved by a trier of fact at trial.c

2. The Plaintiff Cato Lee and the Defendant LaRue

"Buster" Haigler.

Threddie Lee Stewart was not the only Lowndes County Negro

- 19-

involved in civil rights activity who felt the wrath of "Buster"

Haigler, and had a long-standing financial arrangement suddenly

and arbitrarily terminated.

In 1962 Haigler loaned Cato Lee funds with which to

* /build a house and secured this loan with a mortgage (6 ).

Thereafter, Haigler made other money advances (7).

In July 1965.) Haigler sent for Lee (25) and, referring

to a little notebook, said he understood that Lee had three

children enrolled in the white school (26). He told Lee the

children would not pass (2 7), that he had already talked to

another man who agreed to withdraw Negro children from the white

school (26,45), and that all the white people would be angry

with Lee if he didn't withdraw his children (4-5). Haigler further

informed Lee that E. L. James stated "that he is through with

Cato" and "he ain't going to let you haul nothin' else for him"

(27,33,44). In this conversation he also made other veiled

threats (28).

At the end of October or beginning of November Haigler

told Lee to get up the entire amount that was owing right away

(13). Haigler said he asked that Lee withdraw his children from

t J Numbers in parentheses refer to page number of deposition

of Cato Lee, unless otherwise designated.

-2 0 -

the white school, and that Lee refused (14,24). He also asked

Lee if he thought Martin Luther King would put up a house for

him (14). In the course of this conversation Lee complained that

he wasn't getting anymore hauling work from whites. Haigler re

sponded, "Cato, didn't I tell you this was coming". "Haven't any

of your white friends asked you to do any hauling?" (34). He said

it looked like Lee cared more for Martin Luther King than he did

for him (35). Haigler also referred to civil rights workers as

"the enemy crowd" (47), and cursed them viciously in foul language

(69).

In 1965 and previous years Lee had hauled extensively for

many white people in Lowndesboro (49). Among them he listed

"Buster" Haigler, Bob Dickson, E.L. James, Buster Meadows and

Allen Meadows (49*50). In February 1966, he was not engaged to

haul for any of the defendants or any other whites (5 1 ). No

white person had given him any hauling work since approximately

September, 1965 (52).

Haigler admitted that he talked to Cato Lee about his

children having applied to the white school (Haigler, deps. 57),

and this has been acknowledged by the trial court, Opinion. p. 3 .

The only other mention of Lee in Haigler's deposition is when he

lists him among those that "died, moved, or cut off themselves".

He testified that "I didn't cut off any of them" (Ha igler, Deps .83).

However, in his affidavit in support of the motion for summary

judgment he no longer insists that he didn't cut Lee off (Haigler,

- 2 1 -

Deps. 83) but rather admits that he did, and the reason for

cutting him off was that the debt "was several years past due".

The testimony is uncontradicted that Lee previously hauled

all of James’ hay and cattle (50) and that James was now not doing

any business with him. James does not deny this and does not try

to explain it away, nor does he deny his purported conversation

with Haigler in which he discussed his intent to boycott Cato

Lee (27,38,44).

One cannot isolate Lee's act of enrolling his children in

the white school for which "... there is strong indication that

Haigler terminated his financial arrangements..." Opinion, 3, and

not infer from it "punishment" for a total involvement in civil

right activity, including voter registration.

The lower Court opinion acknowledges that Lee was fore

closed for asserting his rights. It is apparent from the record

that one of the reasons for these economic sanctions was his

enrolling his children in the white school. The question to be

determined at a hearing is whether this was the sole reason or

whether other civil rights activity, such as voter registration,

also played a role. Having found a showing of economic harass

ment because of the exercise of one protected right, an Inference

may be drawn that the cause of the harassment went deeper than

that. Certainly, having made this much of a showing, plaintiff

should not be foreclosed of an opportunity to prove his conten

tions at a hearing where defendants' demeanor in testifying can

-22

be given close judicial scrutiny.

3. The Plaintiff Muffin Miles and the Defendant

Bess Gardner Beck.

Mr. Muffin Miles, with a family consisting of 11 people,

* /lived on the land of Mrs. Bess Beck for about 10 years (6).-y He

attempted to register in July of 1965 (11) and his wife registered

(17). Both he and his children had attended mass meetings (59,92).

He fed civil rights workers at his home (60) and as far as he knew

he was the only person in Lowndes County who would feed them (91).

One of his daughters had gone out of the state on civil rights

activity (60) and he didn't know of any other family whose

children had gone out of the state in this regard (96).

On November 6, 1965, he was informed by Mrs. Beck that he

would have to be off her land by January 1, 1966 (8,88). She

told him that she couldn't let him stay because his daughter was

"running all up yonder to New York or Washington or somewhere,

butting into this mess of Martin Luther King" (8, 39). She did

not say anything about his two mules and two cows occasionally

getting loose (40). He further testified that she "told all of

her people not to become involved" or that "someday they would

get just what they were looking for" (6 2).

1/ The numbers in parentheses refer to page numbers in the

deposition of Muffin Miles, unless otherwise designated.

- 23-

Defendant Beck denied that she made any remarks about

Dr. King or Miles' daughter (Beck, Deps. 12). She claimed that

her reason for putting Miles off the land was that he was "not

a desirable tenant" (Beck, Deps. ll), as his stock strayed and

he worked in Montgomery (Beck, Deps. ll). However, when she told

him to vacate the premises she did not articulate any of these

reasons as "he didn't ask"(Beck, Deps. 18). She also testified

that he was the only one she put off the land (Beck, Deps. 8)

and that she had not put anyone off in the past two years (Beck,

Deps. 9).

Defendants, in their motion for summary judgment stressed

the fact that there was no testimony or evidence that Miles'

tenancy was terminated because of his having attempted to register

to vote, and that there was no conversation about voter registra

tion between Beck and Miles.

If, to sustain their position against a motion for summary

judgment, plaintiffs must prove an actual conversation in which

the defendant threatens plaintiff with reprisals for specific

registration activity, then, in this particular Instance, the

proof is not readily available. However, we would respectfully

submit that the proof requirements to withstand the motion for

summary judgment are not so hopelessly stringent. From the testi

mony taken as a whole it is reasonably inferable that Miles was,

in fact, evicted because of civil rights activity on the part of

himself and those under his control. Here plaintiff and his wife

- 24-

both registered or attempted to register. Plaintiff attended

meetings of the civil rights movement and his children were

active participants in all phases of civil rights activity, es

pecially one daughter whose activities particularly angered

defendant Beck. When defendant Beck ordered plaintiff Miles from

her land without stating a reason and revealed her displeasure

at that "mess of Martin Luther King" she was punishing him for

voter registration activity as clearly as if she had articulated

that as her reason for the ''termination of the tenancy. The

eviction stands to notify not only the Miles family, but every

other Negro in Lowndes County, Alabama, that voter registration

will not be tolerated. Defendant Beck, although unable or un

willing to give a reason which did not involve civil rights

participation at the time of the eviction, sought to explain her

motivations at the deposition taking. She stated that she didn’t

explain the termination of a ten year tenancy because "he didn't

ask" (Beck, Deps. 18) but that the reason for the eviction was

that he was "not a desirable tenant" (Beck, Deps. ll). From her

testimony it appears that one of the two factors which contri

buted to this undesirability was that he worked in Montgomery so

that he was not home to farm. However, his wife and nine children

did continue to operate the farm (28). It also appears that she

had three other tenants who "live there and come to Montgomery"

(Beck, Deps. 8) but she did not ask them to leave.

- 25-

4. The P l a i n t i f f s E l i j a h Gordon and G r i l l e Coleman

and the Defendant Mack Champion.

Mr. Gordon lived all his life on land now owned by

Mack Champion (Gordon, Deps. 4). His wife registered to vote

(Gordon, Deps. 31). On Thanksgiving Day 1965, Champion told him

that he would have an eight-acre allotment. A week later

Champion told him that he would have no allotment (Gordon, Deps.6).

He told him that he did not want any "civil righters" on his

place (Gordon, Deps. 46-47).

After the institution of this action, Champion and his

attorney took Gordon to the U.S. Commissioner in Montgomery

(Gordon, Deps. 40) and then took a written statement from Gordon

regarding the subject matter of the action (Gordon, Deps. 14-17).

Mr. Coleman lived on land now owned by Mack Champion for

19 or 20 years (Coleman, Deps. 30). His wife registered to vote

in June or July of 1965 (Coleman, Deps. 13). Coleman attended

two civil rights mass meetings (Coleman, Deps. 36). In July 1965,

Champion told him that he knew his wife had registered (Coleman,

Deps. 1 7,19). Before Christmas 1965, Champion told him that he

could not have the land for 1966 (Coleman, Deps. 6,l6 ). He did

not give him any reason for this (Coleman, Deps. 6 ).

After the institution of the action, Champion asked him

to come to Montgomery to sign a statement about the case (Coleman

Deps. 33-34).

- 2 6 -

5. The P l a i n t i f f E l l e n Smith and th e D efendant

Todd Meadows.

For two years (Smith Deps. 6 ) Mrs. Smith rented a house

from Henry Sellers, a Negro (Smith Deps. 10), who rented the bouse

and other property from Mrs. Hagood and her daughter Snooky Gordon.

Todd Meadows then leased the land from Mrs. Hagood for the year

1966 (Smith Deps. 23). Mrs. Smith registered to vote in August

(Smith Deps. 10,31). Three of her brothers, Hardy Lee, Cato Lee,

and Bright Lee, are plaintiffs in this action (Smith Deps. 32,33).

Another brother, Amos Lee, also had to move (Smith Deps. 32). Be

fore Christmas 1965, Henry Sellers told her that Todd Meadows had

said that she had to move by January 1st, as did Sellers and her

brother, Bright Lee (Smith Deps. 9,16,22,40).

Todd Meadows testified that he leased the land for the

year 1966 for cotton acreage. He wanted the tenants off the land

as they worked elsewhere and he wanted tenants who would work the

land. He did not ask them if they were interested in working the

land, nor did he have any new tenants in mind when he told them to

leave the land. Moreover, by the end of February, with cultivating

season beginning in April or May, he still did not have any tenants

(Todd Meadows Deps. 24).

The unusual circumstances of Mrs. Smith being thrown off

the land concurrently with her brothers is especially significant

in light of the close interconnections between Mr. Meadows and the

other defendants. Particularly is this so since Mr. Meadows own

explanation is self-contradictory.

- 2 7 -

6. The Plaintiff Jack Crawford and the Defendant

Robert Dickson.

Mr. Crawford was 82 years old, hard of hearing and nearly

* /

blind (4,8). He lived on land owned first by Robert Dickson's

father and then by Dickson, for 47 years (23). Crawford register

ed to vote in August 1965, as did Mrs. Nancy McCall and his grand

child, who were living with him (34). In November 1985 (8), Dick

son told Crawford that he would have to move because Dickson was

offended by an article which appeared in Look Magazine (7,8,10,14)

about civil rights problems in Lowndes County, and in which

plaintiff Crawford was quoted. While he argues that he considered

the article to be a slur against his father, this explanation can

hardly be accepted at face value in light of the entire pattern

which the depositions revealed.

7 . The Plaintiff Sidney Logan and the Defendant

Fred Holladay.

In i960 defendant Holladay loaned plaintiff Logan $3000.

secured by a mortgage. The mortgage was for ten years and called

for annual payments of $350.00 each (Logan Deps. 5,6,7). Logan

did a considerable amount of hauling work for Holladay--in some

years amounting to approximately $1000.00 (Holladay Deps. 22) At

the end of each year they would apply his earnings from hauling

against his debt (Logan Deps.12). Prior to December 1965,

Holladay never asked for any payments on the mortgage other than

Numbers in parentheses refer to page number of deposition

of Jack Crawford, unless otherwise designated.

- 2 8 -

the annual settlement (Logan Deps. 8,13). In December 1965, with

out any explanation, Holladay demanded the entire unpaid balance

(Logan Deps. 8,13). That this was not unrelated to the activities

in Lowndes County is revealed by the relationship between Holladay

and the various defendants, discussed below.

We deem it unnecessary at this point to detail the testi

mony with respect to the remaining plaintiffs or parties or the

circumstances under which they were asked to leave, for this is

hardly the time for a final adjudication of the rights of the

*/parties. The same kinds of conflict of questions of fact between

the testimony the other plaintiffs and defendants repeated

throughout the depositions and its inclusion in this brief would

only be cumulative. It is sufficient to state that these key

questions exist and must be resolved by the trier of fact at a

hearing where witness credibility can play a major demonstrative

role.

C . The Interconnection of the Defendants

The intimate relations which exist among the several de

fendants indicate that the program under way does not represent

the individual actions of separate landlords. The concurrence in

point of time of all these actions taken by the several landlords,

in the light of testimony establishing their close business and

social relations, leaves more than an inference that the

*7 We have, of course, covered all of the defendants other

than Allan Meadows whose motion for summary judgment was not

supported either by affidavit or deposition.

- 2 9 -

evictions were the result of a general understanding among the

defendants. The testimony of the defendants and their "interest

in the result of the suit" (Sonnentheil v Christian Moerlein

Brewing Co., 172 U.S. 1*01, 408 (1899) must also be carefully

scrutinized.

According to the i960 United States Census Lowndes

County has a population exceeding 15,^00, and covers a land area

of 716 square miles. Yet among the defendants we find that all

of them are either related by blood to at least one other defen

dant or are close personal friends. The full impact of the con

spiratorial aspect of the movement to expell plaintiffs from

Lowndes County is appreciated when the interconnection between

the various defendants are outlined:

E. L. James testified that he sees Buster Haigler quite

often, that they visit at each others homes and play cards to

gether (James Deps. 25,26). They number among their mutual

friends, with whom they have personal contacts at home or card

parties, Robert Dickson, Todd Meadows and Buster Meadows (James

Deps. 26). There is a group of 6 or 8 who play card periodically

(James Deps. 33).

LaRue "Buster" Haigler acknowledged that he has been

knowing James "ever since he was a kid" (Haigler Deps. 50) al

though he did not mention their frequent visits or card games

(James Deps. 26). He has also been knowing Buster Meadows all of

his mature years (Haigler Deps 4) and knows Todd Meadows and his

-3 0 -

father before him (Haigler Deps. 49). He testified that he was

related to Champion (Haigler Deps. 49), has been knowing Dickson

and his family all of his life (Haigler Deps. 49), also knows

Bess Beck and her parents (Haigler Deps. 50), and has known

Holladay for a long time. (Haigler Deps. 51).

Todd Meadows is the nephew of Buster Meadows. He sees

his uncle once or twice a week. They are adjoining land owners

(Todd Meddows Deps. 17). Allen Meadows is a second or third

cousin. Todd Meadows sees James at church and at some Christmas

parties (Todd Meadows Deps. 18). He used to date Haigler's

daughter and was in his home quite frequently but now "I very

rarely see him, just at Farm Bureau Meetings or cattle meetings,

Cattle Association rather or something like that or social

functions together." (Todd Meadows Deps. 18). Likewise, his

relationship with Dickson is a business one and he sees him at

church, but "we have very few social contact " (Todd Meadows

Deps. 17). This is in direct contradiction to the testimony

of James that he and Haigler have "personal contacts at home or

card parties and so forth" with Robert Dickson, Todd Meadows and

E.R. "Buster" Meadows (James Deps. 26). Todd Meadows knew

Champion at school but rarely sees him now (Todd Meadows Deps. 17)

and sees Holladay at Dickson's place of business (Todd Meadows

Deps. 18).

E. R, "Buster" Meadows testified that he sees his

nephew Todd regularly (E.R. Meadows Deps. 19). He is also

- 3 1 -

related to Allen Meadows, but seldom sees him (E.R. Meadows Deps.

19,20). He also admits to seeing James regularly and visiting

him socially (E.R. Meadows Deps. 20) but testified that be only

sees Haigler when be goes to Haynesville to "pay taxes or buy

my truck tags or something like that ..." (E.R. Meadows Deps. 20).

This is contradicted by James who says that he, Haigler and

Buster Meadows are mutual friends and they have personal contacts

at home (James Deps. 25). Buster Meadows sees Dickson at his

stockyards and at church but says he doesn't play cards "but very

seldom, maybe once or twice during Christmastime" (E.R. Meadows

Deps. 19). He also sees Holladay out at Dickson's place of

business (E.R. Meadows Deps. 21).

Robert Dickson, Jr. is in the stockyard business and

has business dealings with all of the defendants and has known

them all for a long time, although he does not know Allen Meadows

as well as he knows the others (Dickson Deps. 17).

Mack Champion lives in the same town as Haigler and is

related to him (Champion Deps. 36). He is a social acquaintance

of Dickson (Champion Deps. 33) and Todd Meadows, having gone to

school with the latter (Champion Deps. 3*0 • He has known Buster

Meadows (Champion Deps. 3*0 and Mrs. Beck all of his life (Cham

pion Deps. 35). He has only known James in the past few years

and their contact was mostly at church (Champion Deps. 37) but

has known Holladay well and had known him all of his life.

Fred Holladay at first seemed reluctant to admit know

ing the other defendants. When asked about Dickson his response

- 3 2 -

was, "I believe I know him"(Holladay Deps. 29). However, he

later admits to knowing Dickson all of his life (Holladay Deps.

29). He also has known Todd Meadows, Buster Meadows, and Macrk

Champion all of their lives, and has known James 25 or 30 years.

Holladay Deps. 30). He sees Mack Champion at least once a week

(Holladay Deps. 68). He does not know Allen Meadows, but is a

first cousin of Bess Beck (Holladay Deps. 29).

The connections, relationship, and friendship between

Dickson, James, Haigler, and the Meadows' is especially interest

ing in light of the fact that all of them, with the exception

of Todd Meadows, were former customers of Cato Lee’s hauling

operation and have all since terminated his services.

D. The Atmosphere at the Deposition Taking

did not Afford' the' Trier of Facts the

Opportunity for Evaluation of Either

tne Conflicts of Testimony'"or fch'e Unre

liability of the Defense Testimony.

The question of opportunity to cross-examine by means

of deposition taking, raised by the Court below as the point on

which to distinguish Poller v. CBS, 368 U.S. 464 (1962), must be

viewed in light of the framework in which this "opportunity" was

presented. Unfortunately, it is impossible to convey the atmos

phere of the deposition taking, the hostility and arrogance of

the defendants. However, we feel it is important to set out

excerpts of the testimony of the defendants to sustain our con

tention that even assuming arguendo that depositions may be

- 3 3 -

considered the equivalent of cross-examination for the purpose of

whether a summary judgment should be granted in some cases, they

certainly cannot serve that purpose here.

We are not dealing with ignorant, illiterate defendants

who would have genuine difficulty in understanding a question,

or who would not be cognizant of a series of events of great

social significance which transpired in their county, but rather,

we are dealing with successful landowners and businessmen, several

of whom are college educated.

Defendant James testified that he had casual conver

sations regarding Negro voter registration with various groups

on the streets (James Deps. 24,25) and that there was a good

possibility that he discussed the voter registration drive with

Dickson, Todd Meadows, Buster Meadows, and Haigler (James Deps.

26,27). Haigler stated that everyone knew of Negroes trying to

register (Haigler Deps. 52) and Todd Meadows agreed that Negro

voter registration was a fairly common subject of conversation

with the people with whom he visited (Todd Meadows Deps. 16).

Strangely, Dickson did not know and "hadn't heard tell"

that Negroes had difficulty in registering (Dickson Deps. 21).

Although he had two and a half years of college he was not curious

as to why the federal registrars were in the county (Dickson Deps.

22) and he took it as a routine matter (Dickson Deps. 25). He

said that the Selma to Montgomery march was not discussed widely

with anybody that he talked to (Dickson Deps. 34). Although he

-3 4 -

knew that the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee was SNCC

he did not know what SNCC was (Dickson Deps. 62). He also testi

fied that there were Negroes registered in Lowndes County prior

to March 1965 (Dickson Deps. 71) and that whites had voting pro

blems in Alabama until the passage of the Civil Rights Bill

(Dickson Deps. 70).

Holladay testified that there were 4 or 5 Negroes on

the poll list in 19^8 or 1950 (Holladay Deps. 3 1 ) 7 With the

same insouciance that characterized Dickson's testimony he stated

that he did not discussed Negro voter registration with anyone

(Holladay Deps. 32) and did not know of any difficulties in con

nection with voter registration (Holladay Deps. 33). Furthermore,

he did not know anything about civil rights activities in the

county in 1965 (Holladay Deps. 52).

Mack Champion, a graduate of Auburn and a school teacher

in the Lowndes County Public school system actually claimed that

he did not know what the lawsuit against the Lowndes County Board

of Education was for (Champion Deps. 116).

Unfortunately, the attitude of mockery was not confined

to the defendants alone. The record is replete with hostility

and barbed attacks on the attorneys for plaintiffs by defendants1

counsel. Perhaps the one remark most indicative of the atmosphere

and attitude that prevaded the entire sessions is found on page 66

^_/ As of i960 Lowndes County had no Negro registered voters.

1961 Commission on Civil Rights Report, Voting, p. 26.

- 3 5 -

of the Holladay deposition:

Mr. Quaintance: (Attorney for the Justice

Department): "That is what

Mr. Kohn said, Nigger."

Mr. Kohn (Attorney for defendant Robert Dickson,Jr.)

"I want to say for the record

that I am going to continue to

say it as long as I live."

With testimony of this nature being elicited at the

deposition taking, and with the atmosphere of hostility and in

tolerance-. that prevailed it seems fairly evident that it was

impossible to engage in a successful pursuit of the truth and that

the opportunity to cross-examine which may normally be available

at a deposition taking cannot in any way be here construed as

sufficient for the purpose of weighing it as a factor in deciding

whether to grant the motion for summary judgment.

Another factor which also affected the depositions and

destroyed their use as a basis for final adjudication of fact was

the atmosphere of harassment. The detailed examination of the

plaintiffs as to the mechanics of the lawsuit— how they retained

counsel, whether they knew that a complaint was filed, etc., could

not but have had the effect of intimidating the plaintiffs, which

of course was what was intended.

We will discuss this in detail below, but feel it is

necessary here to point out that even after a conference in which

-3.6-

the Court below advised counsel that they should avoid this

trivia and get on with the substance of the action, counsel for

the defendants persisted in this uncalled for line of questioning.

Counsel would not have dared to do this in open court and had

the interrogation been pursued in open court before the trier

of fact the plaintiffs would not have been inhibited in their

testimony.

E. The Standards for the Evaluation of

the Deposition Testimony.

This Court has, of course, on many occasions made clear

that it has a thorough understanding of the intricacies and sub-

leties of the denial of rights to Negroes in the South today.

This case is but another example of the need for sophisticated

scrutiny. To the extent that what is involved is proof of motive

and intent, this Court is of course well aware that currently

it is no longer fashionable to admit that one is denying Negroes

their constitutionally protected rights.

In the earliest civil rights cases those parties who

sought to deny to Negroes their constitutional rights were out

spoken regarding their motive and intent. Restaurant owners

didn't tell Negroes they couldn't come in because the restaurant

was full, or because they weren't properly attired, nor did they

turn them away without explanation. The made their reasons for

refusal very plain. See, for example, Peterson v. Greenville,

- 3 7 -

373 U.S. 244, 246 (1963)j Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267, 268

(1963); Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153, 154 (1964); Hamm v.

Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306, 309 (1964). By the same token the old

jury cases which developed were virtually uncontested regarding

the Intentional exclusion of Negroes. See, Pierre v. Louisiana,

306 U.S. 354, 361 (1939). But now, in light of the Court’s action

in attempting to strike down every effort to withhold the vest

ments of first class citizenship, the opponents of civil rights

have grown much more subtle. Negroes who seek service in places

of public accomodations are given various reasons why they cannot

use the facilities, none of which have anything to do with race.

See record in Shields v. Midtown Bowling Lanes, 11 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 1492 (C.A. No. 853, M.D. Ga., Albany Div., Feb. 8, 1966).

Landlords who evict Negroes from tenancies of long standing do not

articulate any reason. United States v. Harvey, 250 F. Supp. 219

(E.D. La., 1966). Jury commissioners testify that they follow the

jury statutes to the letter although great numerical inequality

still exists. Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 446, 480-481 (1953);

Brookins v. State, 221 Ga. 181, 144 S.E. 2d 83 (1965).

No longer are questions of a subjective nature such as

"intent" blatantly answered for us, but we must draw inferences

from the facts. To establish conclusions of a subjective

character, one must offer in proof, material, objective facts

from which the inference of subjectivity may or may not be drawn

by the trier of facts. Perhaps the leading case explaining this

- 38-

mode o f p r o o f i s S t e v e n s o n v. U nited S t a t e s , 162 U .S . 313 ( 18 9 6 ):

"Malice in connection with the crime

of killing is but another name for a cer

tain condition of a man's heart or mind

and as no one can look into the heart or

mind of another, the only way to decide

upon its condition is to infer it from

the surrounding facts, and that inference

is one of fact for a jury." at 320.

See also, Morissette v. United States, 342 U.S. 246 (1951);

Stephen, 2 History of the Criminal Law III. Once these facts have

been testified to, inferences going to subjectivity can be drawn.

The substantial conflicts in testimony and the existence

of valid, unresolved questions of fact require this Court to

reverse the granting of the summary judgment.

II

THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN IMPOSING

COSTS AGAINST ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

Having erroneously granted the motion for summary

judgment, the court’s determination that plaintiffs’ attorneys

must bear the costs must fall. However, assuming for the sake

of argument that it was appropriate to grant a summary judgment

in this instance, the court's determination as to the taxation

of costs must nevertheless be reversed because it was without

power to assess costs against the attorneys for the plaintiffs,

and even if the court had this extraordinary power its action

in assessing these costs without a hearing or notice was a

denial of due process.

-39

A . The Court Below had no Basis In

Fact for Assessing the Costs

herein Against the Attorneys.

In its opinion entered on the 15th day of June, 1966,

the Court stated:

"The testimony of the plaintiffs as

now presented in several depositions re

flects that none, or practically none,

of the plaintiffs specifically authorized

the filing of this lawsuit, or, as a

matter of fact, realized that it has been

filed until they were called upon to

appear for the purpose of testifying."

(R. 369 [op.5 ]).

The Court below then went on to state that it assumed

that "representatives of certain ’Civil Rights Organizations’

contacted these plaintiffs" and employed the attorneys who filed

this action. Therefore, the court held that, "justice requires

the taxation of costs against the attorneys who filed the case."

(R. 369 [op.5]).

In the interest of correcting this erroneous impression

on the part of the Court below, appellants filed a motion for

reargument under Rule 56, F.R.C.P. on the 1st day of July, 1966

(R. 371-383). On July 5, 1966, the Court below denied said

motion (R. 38^) without argument.

As appellants' motion for reargument sets out in detail

a clarification of the facts we refrain from burdening the Court

with a lengthy repetition, and respectfully refer said motion

to the Court's attention. However, we do wish to emphasize some

of the matter set out in said motion, below.

-4 0 -

The Court erred when it held that "none,, or practically

none of the plaintiffs specifically authorized the filing of

this lawsuit." On file as part of the record in this case are

copies of retention agreements, executed by each of the plaintiffs

below authorizing the attorneys

"to institute and prosecute such liti

gation in Federal and State Courts as

they may deem appropriate to stop whole

sale evictions by plantation owners

without justifiable reason or notice, to

take such steps by litigation or other

wise to stop such intimidation of Negroes

who have registered to Vote."

All of these retention agreements were obtained prior to the

institution of this litigation.

During the course of the deposition taking it became

clear that defendants below were purusing the issue of retention

of counsel and the facts surrounding the institution of the action

Mr. William Messing, one of the attorneys representing the plain

tiffs at the deposition taking, sought to cross-examine with

respect to these matters, see Affidavit of William L. Messing, Esq

appended to motion for rehearing, supra (R. 377-383)* to estab

lished the fact that there was written authorization for the

institution of this action. As defendants' counsel objected to

this line of examination, the matter was presented to the Court

below. Judge Johnson stated "that he was not interested in trivia

like the circumstances under which the plaintiffs counsel were

retained or the action instituted" and admonished counsel to get

on with the substance of the action (Messing affidavit, supra,)

(R. 378).

-l+l-

In view of this ruling Mr. Messing did not deem it

appropriate or necessary to submit the written retainers. However

despite the ruling of the Court below, defendants continued to

question plaintiffs regarding these irrelevancies.

There are really two separate and distinct questions

here, but unfortunately they seem to have become oonfused and

intertwined. The first issue is whether the plaintiffs retained

the attorneys who represented them in the course of the litigation

Above, we have made it demonstrably clear that this question

must be answered affirmatively. The signed retainers are a part

of the record before this Court (R. 38O-383). Therefore, plain

tiffs' attorneys were authorized to act and just because a group

of the plaintiffs may not have understood some of the nuances of

the litigation, this in no way can be the basis of a finding that

the attorneys were not retained by plaintiffs.

The second issue which has been mixed with the question

of whether counsel acted without the authorization of the plain

tiffs is whether some of the plaintiffs were in effect seeking

to withdraw from the litigation during the deposition taking.

Assuming arguendo that some plaintiffs were seeking to withdraw

from the litigation, several distinct sub-issues are raised.

Firstly, plaintiffs in a class action may only withdraw

with the approval of the court. Rule 23(c), Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure; Masterson v. Pergament (6th Cir., 1953) 203

F .2d 315.

4 2 -

The reason for the Rule is quite apparent.

"The purpose of this provision is

the protection of other members of the

class against unjust or unfair settle

ments in case a plaintiff who starts

the action become faint hearted before

its completion or secures satisfaction

of his individual claim or compromise."

2 Barron and Holtzoff, Federal Practice

and Procedure § 570, at 331 (Rules ed.

1961).

See also, Nix v. Dukes, 58 Tex. 98 (1882); Note, 17 Corn. L.Q.

140 (1931)] Whitten v. Dabney. 171 Colo. 621, 154 P. 312, 316;

State ex rel. Milwaukee v. Ludwig. 106 Wise. 226, 82 N.W. 158,

160-161 (1900).

To make a just determination of whether to approve the

withdrawal of a class action plaintiff the court must determine

what would serve the best interests of the class. To accomplish

this end the court must first determine whether the proposed with

drawal is genuinely motivated or is caused by fear, harassment

and similar circumstances causing a "faint hearted" effect.

Although plaintiffs' educational attainments are not a

part of this record, it is clear that they were all life long

residents of rural Lowndes County, and that, therefore, their