United Steelworkers of America (AFL-CIO-CLC) v. Goodman Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

March 9, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United Steelworkers of America (AFL-CIO-CLC) v. Goodman Brief Amici Curiae, 1987. b544b4e2-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9b679a43-0498-4a1a-b3b1-baae0ae6bab9/united-steelworkers-of-america-afl-cio-clc-v-goodman-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

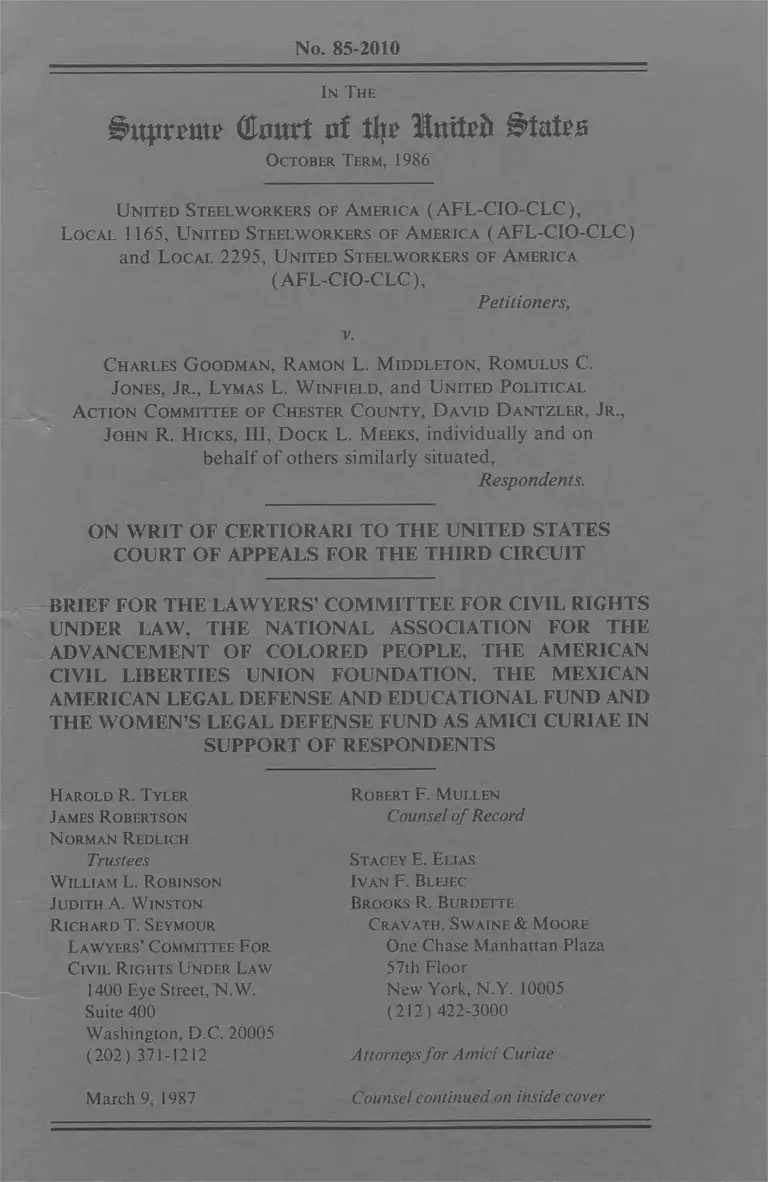

No. 85-2010

In The

ûprinni' Court of tltr Jlnttrii Stairs

October Term, 1986

United Steelworkers of America (AFL-CIO-CLC),

Local 1165, United Steelworkers of America (AFL-CIO-CLC)

and Local 2295, U nited Steelworkers of America

(AFL-CIO-CLC),

Petitioners,

v.

Charles G oodman, Ramon L. M iddleton, R omulus C.

Jones, Jr., Lymas L. W infield, and United Political

Action Committee of Chester County, D avid D antzler, Jr.,

John R. H icks, III, D ock L. Meeks, individually and on

behalf of others similarly situated,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, THE AMERICAN

CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, THE MEXICAN

AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND AND

THE WOMEN’S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND AS AMICI CURIAE IN

SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Harold R. Tyler

James Robertson

N orman Redlich

Trustees

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A. W inston

R ichard T. Seymour

Lawyers’ Committee For

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

March 9, 1987

Robert F. Mullen

Counsel of Record

Stacey E. Elias

Ivan F. Blejec.

Brooks R. Burdette

Cravath, Swaine & Moore

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

57th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10005

(212) 422-3000

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

Counsel continued on inside cover

Grover G. Hankins

Joyce H. Knox

National Association

F or The Advancement

Of Colored People

4805 Mount Hope Drive

Baltimore, Maryland 21215

(301) 358-8900

Joan Bertin

Joan G ibbs

American Civil Liberties

Union F oundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, N.Y. 10036

(212) 944-9800

Antonia Hernandez

E. R ichard Larson

Theresa Bustillos

Mexican American Legal

Defense And Educational

Fund

634 South Spring Street

Los Angeles, California 90014

(213) 629-2512

Judith L. Lichtman

Claudia Withers

Women’s Legal Defense Fund

2000 P Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 887-0364

Attorneys for Amici CuriaeAttorneys for Amici Curiae

Page

T able of A u th orities ............................................................. ii

C onsent of P arties................................................................. 2

Interest of A mici Cu r ia e ...................................................... 2

Statement of the C a se .......................................................... 3

Summary of A rgument.......................................................... 3

A rgument................................................................................... 5

I. THE UNIONS’ DISCRIMINATORY FAIL

URE TO PROCESS RACIAL GRIEVANCES

VIOLATED TITLE VII AND SECTION 1981... 5

A. Under Title VII A Union Cannot Treat The

Right To Freedom From Discrimination

Less Favorably Than Other Rights Se

cured Under A Collective-Bargaining

Agreement.................................................... 6

B. The Unions’ Deliberate Refusal To Process

Racial Grievances Violated Section 1981. 10

II. UNION LIABILITY UNDER SECTION 1981

AND TITLE VII FOR REFUSAL TO FIGHT

EMPLOYER DISCRIMINATION IS CON

SISTENT WITH NATIONAL LABOR RELA

TIONS POLICIES.................................................. 11

A. Construing Title VII And Section 1981 To

Prohibit A Union From Discrimination In

The Processing Of Members’ Grievances

Is Consistent With The Duty Of Fair

Representation............................................ 11

B. Requiring A Union To Meet Its Obligations

Under Title VII And Section 1981 Im

poses No Excessive Burdens Upon

Unions.......................................................... 13

III. A UNION MAY NOT COMPROMISE

RIGHTS SECURED BY TITLE VII OR SEC

TION 1981............................................................... 14

IV. DISCRIMINATION CAN BE EFFECTIVELY

ELIMINATED ONLY IF IT IS EXPOSED....... 17

C onclusion ................................................................................ 21

TABLE OF CONTENTS

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) .... 14,15,18

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 ( 1974) .. 13

Anderson v. City o f Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564 (1985) . 10

Altman v. Stevens Fashion Fabrics, 441 F. Supp. 1318

(N.D. Cal. 1977) ........................................................... 18

Bibbs v. Block, 778 F.2d 1318 ( 8th Cir. 1985) ................ 17

Bonilla v. Oakland Scavenger Co., 697 F.2d 1297 (9th

Cir. 1982), cert, denied, 467 U.S. 1251 (1984) .......... 8

Burnett v. Grattan, 468 U.S. 42 (1984) ........................... 7

Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal, Inc., 458 F. Supp. 252 (N.D.

Ind. 1977)........................................................................ 8,9

Diaz v. American Tel. & Tel., 752 F.2d 1356 (9th Cir.

1985) ............................................................................... 17

Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western Addition Community

Org., 420 U.S. 50 (1975) ............................................... 13, 15, 16,

17

EEOC v. Local 638 . . . Local 28, Sheet Metal Workers’

In t’l Ass’n, 532 F.2d 821 (2d Cir. 1976), a ff’d, sub

nom. Local 28 o f Sheet Metal Workers’ In t’l Ass’n,

106S. Ct. 3019 (1986) .................................................. 18

General Bldg. Contractors Ass’n v. Pennsylvania, 458

U.S. 375 (1982) .............................................................. 10

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 580 F. Supp. 1114 (E.D.

Pa. 1984), a ff’d in part, rev’d in part, vacated in part,

111 F.2d 113 (3d Cir. 1985), reh’g denied, 40 Emp.

Prac. Dec. (CCH) f 36,153 (3d Cir.) (en banc),

cert, granted, 107 S. Ct. 568 ( 1986) ............................. passim

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ............. 13

Howard v. International Molders and Allied Workers

Union, AFL-CIO-CLC, Local #100, 779 F.2d 1546

(1 1th Cir.), cert, denied, 106 S. Ct. 2902 (1986) ....... 8

Hughes Tool Co., 147 N.L.R.B. 1573 (1964)................... 16

International Bhd. o f Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324(1977) .............................................................. 7

Local Union No. 12, United Rubber, Cork, Linoleum &

Plastic Workers o f America v. NLRB, 368 F.2d 12

(5th Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 837 (1967) .... 16

Ill

Page

Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d 979

(D.C.Cir. 1973) ..................................................... 8,9,11

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co., 427 U.S. 273

(1976) ............................................................................. 15

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ................................. .......................................... 7

Nix v. Williams, 467 U.S. 431 (1984) ............................. 18

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982) ......... 10

Reeder-Baker v. Lincoln N at’l Corp., 649 F. Supp. 647

(N.D. Ind. 1986) ........................................................... 18

Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d 333 ( 10th Cir.

1975) ............................................................................... 18

Stamford Bd. o f Educ. v. Stamford Educ. Ass’n, 697

F.2d70 (2d Cir. 1982) .................................................. 17,18

Steele v. Louisville & N. R.R., 323 U.S. 192 (1944) ...... 12

Stephenson v. Simon, 448 F. Supp. 708 (D.D.C. 1978) . 18

Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257 (D.C. Cir. 1982) 18

Toney v. Block, 705 F.2d 1364 (D.C. Cir. 1983) ............. 18

Tunstall v. Brotherhood o f Locomotive Firemen, 323

U.S. 210 (1944) ............................................................. 13

United States v. Ceccolini, 435 U.S. 268 (1978) ............. 18

United States v. N. L. Indus., Inc., 479 F.2d 354 (8th

Cir. 1973) ........................................................................ 15

Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171 (1967) ................................. 11,12, 13,

16

Wallace Corp. v. NLRB, 323 U.S. 248 (1944) ................ 16

STATUTES

Fed. R. Civ. P. 5 2 ( a ) ................................................. 10

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L.

No. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241, (July 2, 1964), codified

as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et. seq. (1982) . passim

Section 703(c), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(c) .............. passim

42 U.S.C § 1981 (1982) ............................................ passim

MISCELLANEOUS

110 Cong. Rec. 2732 (1964) ..................................... 19

Note, Union Liability fo r Employer Discrimination,

93 Harv. L. Rev. 702 (1980) ............................... 11, 12

No. 85-2010

In T he

( ta r t at % States

October T erm, 1986

United Steelworkers of America ( AFL-CIO-CLC),

Local 1165, U nited Steelworkers of America (AFL-CIO-CLC)

and Local 2295, U nited Steelworkers of America

(AFL-CIO-CLC),

Petitioners,

v.

Charles G oodman, Ramon L. M iddleton, R omulus C.

Jones, Jr., Lymas L. W infield, and U nited Political

Action Committee of Chester County, D avid D antzler, Jr.,

John R. H icks, III, D ock L. Meeks, individually and on

behalf of others similarly situated,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, THE AMERICAN

CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, THE MEXICAN

AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND AND

THE WOMEN’S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND AS AMICI CURIAE IN

SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

2

Petitioners and respondents have consented to the filing of

this brief. Petitioners’ letter of consent is being filed herewith.

Respondents’ letter of consent has been filed with the Clerk of

the Court.

CONSENT OF PARTIES

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

(“Lawyers’ Committee” ) is a nationwide civil rights organiza

tion that was formed in 1963 by leaders of the American Bar, at

the request of President Kennedy, to provide legal representa

tion to blacks who were being deprived of their civil rights. The

national office of the Lawyers’ Committee and its local offices

have represented the interests of blacks, Hispanics and women

in hundreds of class actions relating to employment dis

crimination, voting rights, equalization of municipal services

and school desegregation. Over one thousand members of the

private bar, including former Attorneys General, former presi

dents of the American Bar Association and other leading

lawyers, have assisted the Lawyers’ Committee in such efforts.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People is a New York nonprofit membership corporation. Its

principal aims and objectives include promoting equality of

rights and eradicating caste or race prejudice among the citizens

of the United States and securing for them increased opportu

nities for employment according to their ability.

The American Civil Liberties Union is a nationwide,

nonpartisan organization of over 250,000 members dedicated

to preserving and protecting the civil rights and civil liberties

guaranteed by the Constitution and the laws of the United

States.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund is a national civil rights organization established in 1967.

Its principal object is to secure through litigation and education,

the civil rights of Hispanics living in the United States.

3

The Women’s Legal Defense Fund (“WLDF”) is a

nonprofit organization founded in 1971 to advance women’s

rights. It represents women in employment discrimination

litigation, operates an employment discrimination counseling

program, conducts public education and represents women’s

interests before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion and other Federal agencies. A major priority for WLDF is

its Employment Rights Project for Women of Color.

Amici have a direct interest in the law governing the

construction and application of the civil rights statutes. Amici

and those individuals whom amici represent litigate under these

statutes regularly and thus have a strong incentive to prevent

diminution of the statutes’ powers as sources of redress for civil

rights violations.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Amici Curiae incorporate the Statement of the Case sub

mitted by respondents herein.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The pervasive flaw in the arguments put forth in the briefs

of petitioners and the Solicitor General is that they set out and

attempt to resolve issues that are not now before this Court.

The narrow question presented here is if a union, when

requested by its minority membership to process meritorious

racial grievances, refuses to do so solely because those griev

ances are based upon racial discrimination, does that union

violate Sections 703(c)(1) and (3) of Title VII (“Section

703(c)” or “Title VII” ) and 42 U.S.C. § 1981 (“Section

1981” ).

Holding a union liable under Title VII and Section 1981

for its deliberate decisions not to attempt to eliminate employer

discrimination prohibited by the collective-bargaining agree

ment is consistent with national labor policy. It grants to a

4

union’s minority membership the added protection of tempe

rance of a policy principled upon majority rule. Even under the

National Labor Relations Act, where a union is the certified

collective-bargaining agent for its membership, that union has a

duty fairly to represent each union member in negotiating a

collective-bargaining agreement and in enforcing that agree

ment equally for all members. The National Labor Relations

Board has determined that deliberate failure to process racial

grievances is a breach of that duty. At a minimum, practices

that violate that duty should be prohibited under Title VII and

Section 1981.

Thus, this Court’s affirmance of the decision of the Court of

Appeals for the Third Circuit would create no significant

additional burdens or obligations because most of those sug

gested herein already exist under the National Labor Relations

Act. Moreover, squarely confronting an employer with racial

discrimination grievances will persuade the employer to end

discriminatory practices and will result in fewer grievances for

the union to process overall.

The clear purpose of Title VII and the Civil Rights Act of

1866 (which includes Section 1981), is to eliminate dis

crimination and the harmful effects of decades of discriminatory

practices. Deterrence of discrimination can best be effected if

discriminatory conduct is brought out in the open. Grievances

that ignore the motivating factor of discrimination in the

conduct complained of, while they may serve to repair some of

the damage done to a single individual, cure merely the

symptom, but not the disease. Charges of discrimination

stigmatize the individuals at whom they are aimed, making it

more likely that unlawful practices will be terminated. When a

union singles out meritorious racial grievances for less favorable

treatment than all other meritorious grievances, it not only

engages in illegal discrimination itself, but it also causes the

perpetuation of illegal discrimination by the employer.

In litigating cases against employers with union contracts,

Amici herein have repeatedly encountered the same factual

5

pattern as the instant case. There is virtually always a

collective-bargaining agreement with a nondiscrimination

clause, but most of the unions have never processed a single

claim under the nondiscrimination provisions, and have en

gaged in the practice of characterizing discrimination claims as

some form of nonracial grievance or otherwise not processing

the claims at all. These practices have, in fact, done nothing to

eliminate entrenched patterns of discrimination; litigation

against the employer was still necessary.

When a union seeks piecemeal relief for individual mem

bers by processing “seniority” grievances where possible, in the

long run that union wastes, rather than preserves, its valuable

resources. As long as a union refuses to bring employer

discrimination out into the open, discrimination will continue.

Thus, ignoring the underlying problem will result in a treadmill

of “seniority” or other such claims. This lawsuit is a perfect

example of how fighting the symptom is not enough. Unless

the curative measures are aimed at the disease of dis

crimination, the ultimate goal of Title VII can never be fulfilled.

There will always be another “seniority” grievance to process.

ARGUMENT

I. THE UNIONS’ DISCRIMINATORY FAILURE TO

PROCESS RACIAL GRIEVANCES VIOLATED TITLE

VII AND SECTION 1981.

The unions repeatedly argue that they are not vicariously

liable for the discriminatory employment practices of Lukens.

Petitioners’ Brief at 25-26.1 However, that was not the issue

before either the District Court or the Court of Appeals, nor is it

the issue now before this Court.

Here the question is whether the discriminatory conduct of

the unions, found to be racially motivated, violated the rights of

1 Hereinafter “Pet. Br. at”. References to the Brief of the United

States as Amicus Curiae are “U.S. Br. at”.

6

respondents and created union liability under Section 703(c) of

Title VII2 and Section 1981.3 Amici submit the answer to that

question is yes.

A. Under Title VII A Union Cannot Treat The Right To

Freedom From Discrimination Less Favorably Than Other

Rights Secured Under A Collective-Bargaining Agreement.

Petitioners make the unsupported statement that the only

section of Title VII applicable to the issues herein is Section

703(c)(3), and that the unions cannot be held to have

2 Section 703(c) provides:

Ҥ 2000e-2. Unlawful employment practices

“(c) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for a labor

organization—

(1) to exclude or to expel from its membership, or

otherwise to discriminate against, any individual because of

his race, color, religion, sex, or national origin;

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify its membership or

applicants for membership, or to classify or fail or refuse to

refer for employment any individual, in any way which

would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employ

ment opportunities, or would limit such employment

opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an

employee or as an applicant for employment, because of

such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin;

or

(3) to cause or attempt to cause an employer to

discriminate against an individual in violation of this sec

tion.”

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (1982).

3 Section 1981 provides:

“All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall

have the same right in every State and Territory to make and

enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full

and equal benefit of the laws and proceedings for the security of

persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be

subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and

exactions of every kind, and to no other.”

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ( 1982).

7

“caused” Lukens’ discriminatory practices in violation of that

section. Pet. Br. at 25-26. Their argument fails on two counts.

First, any time a union takes affirmative steps toward avoiding

confrontation with an employer on the issue of racial dis

crimination, that union contributes to the perpetuation of the

employer’s discriminatory conduct in violation of Section

703(c)(3). Second, deliberately deciding not to process racial

grievances protected by Title VII in favor of the promotion of

other rights secured under a collective-bargaining agreement is

discrimination itself and violates Section 703(c)(1)4 as well.5

In choosing to process some, but not all, of the grievances

raised by union members, a union naturally treats some types of

claims differently from others. Where this type of selective

practice is adopted, this Court has set forth the test to determine

whether the procedure constitutes a discriminatory and unlaw

ful employment practice under Title VII. “The ultimate factual

issues are thus simply whether there was a pattern or practice of

such disparate treatment and, if so, whether the differences

were ‘racially premised’.” International Bhd. o f Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324, 335 (1977) (quoting McDonnell

Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 805 n.18 (1973)).

Almost every Federal court that has addressed the issue

has held that under Title VII it is a union’s responsibility to take

an active role in eliminating discrimination where it has the

4 From the commencement of this litigation, respondents herein

asserted claims under both Sections 703(c)( 1) and (3) in the District

Court. That court found that the union had discriminated against the

plaintiff class and that such practices cause perpetuation of employer

discrimination. See Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 580 F. Supp. 1114,

1160 (E.D. Pa. 1984) (“The clear preference of both the company

and the unions to avoid addressing racial issues served to perpetuate

the discriminatory environment.”), aff’d in part, rev’d in part, vacated

in part, 111 F.2d 113 (3d Cir. 1985), cert, granted, 107 S. Ct. 568

( 1986).

5 It is questionable whether any procedure that disfavors Federal

rights is lawful. Cf. Burnett v. Grattan, 468 U.S. 42, 53 n. 15 (1984).

8

power to do so.6 The seminal case, upon which the courts

below relied, is Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478

F.2d 979 (D.C. Cir. 1973). There the court held:

“Where a union has not done so and where there is such

solid evidence of employer discrimination as is alleged

here, it would undermine Title VII’s attempt to impose

responsibility on both unions and employers to hold that

union passivity at the negotiating table in such circum

stances cannot constitute a violation of the Act.”

Id. at 989.

The arguments put forth in both the petitioners’ brief7 and

the Solicitor General’s brief,8 misstate the basic issue and ignore

the findings of fact of the District Court:

“ [T]he evidence in this case proves far more than mere

passivity on the part of the unions. The distinction to be

observed is between a union which, through lethargy or

inefficiency simply fails to perceive problems or is in

attentive to their possible solution . . . and a union which,

aware of racial discrimination against some of its mem

bers, fails to protect their interests.”

Goodman, 580 F. Supp. at 1160; and the Court of Appeals

affirmed echoing portions of the District Court opinion. See

111 F.2d at 126.

6See Howard v. International Molders and Allied Workers Union,

AFL-CIO-CLC, Local# 100, 779 F.2d 1546, 1553 (11th Cir.) (unions

liable under Section 703(c)(3) for failing to make reasonable effort to

end employer’s use of racially discriminatory nonvalid tests for

promotions), cert, denied, 106 S. Ct. 2092 ( 1986); Bonilla v. Oakland

Scavenger Co., 697 F.2d 1297 (9th Cir. 1982) (Title VII and Section

1981 impose upon a union an affirmative obligation to oppose

employment discrimination against its membership), cert, denied, 461

U.S. 1251 (1984); Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d

979, 989 (D.C. Cir. 1973); Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal, Inc., 458 F. Supp.

252 (N.D. Ind. 1977).

7 See Pet. Br. at 26 (describing the issue as the “question of

union responsibility for employer discrimination”).

8 See U.S. Br. at 10 (describing respondents’ theory as holding

the unions liable for their “passive acquiescence in discrimination by

the employer”).

9

The unions argue that they were justified in refusing to

process racial grievances because they could get effective relief

if they categorized such grievances as “seniority” or other

nondiscrimination claims. See Pet. Br. at 42-43. The District

Court, the Court of Appeals and the Macklin line of cases do

not agree with the unions. Disparate treatment by unions of all

grievances that if processed could help eliminate discriminatory

employment practices is discrimination in violation of Title

VII. 9

Moreover, a union’s deliberate refusal to assist its members

in eliminating discrimination encourages and allows an em

ployer to continue discriminatory employment practices. See

Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal, Inc., 458 F. Supp. 252, 261 (N.D. Ind.

1977) (holding that Title VII places an affirmative duty on

labor unions to eliminate discrimination).

Regardless of whether this case is scrutinized under Section

703(c)(1), prohibiting union discrimination, or Section

703(c)(3), prohibiting a union from causing an employer’s

discrimination, liability will lie under Title VII. Given the

broad remedial intent of Title VII, it is in complete accord with

the spirit of that legislation to hold the unions liable for

discriminatory conduct that singles out for nonprocessing griev

ances based upon racial discrimination. 9

9 Moreover, the unions’ argument fails completely with respect to

probationary employees whose rights under the collective-bargaining

agreement are virtually nonexistent. See Goodman, 580 F. Supp. at

1159. Since 1965, the collective-bargaining agreement at issue before

this Court has included a provision prohibiting employers from

discriminating against probationary employees. See id. Dis

crimination is virtually the only legitimate ground upon which a

probationary employee may challenge employer conduct, and the

probationary employee can only make such a challenge if the union

files a grievance. Thus, the unions’ policy of never filing a grievance

on behalf of a probationary employee, see id., is simply another way

of avoiding their obligation to combat discrimination. Although

respondents did not raise the issue below, the unions’ treatment of

probationary employees could be violative of Section 703(c)(2)

prohibiting classification of members in a way that would deprive the

individual of employment opportunities.

10

B. The Unions’ Deliberate Refusal To Process Racial Griev

ances Violated Section 1981.

Both the unions and the Solicitor General argue that

General Bldg. Contractors Ass’n v. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375

(1982), is controlling and that the case proves that Section

1981 “provide[s] no basis for holding a union liable for

discriminatory conduct of an employer”. Pet. Br. at 45; see U.S.

Br. at 25. In General Bldg., this Court overturned a finding of

an employer’s liability under Section 1981 for a union’s dis

crimination because the District Court had found a violation on

proof of disparate impact alone and not upon proof of in

tentional discrimination. Additionally, the employer therein

had no knowledge of the union’s discriminatory practices. 458

U.S. at 383.

In sharp contrast to General Bldg., the District Court herein

found the unions guilty of deliberate and racially motivated

conduct sufficient to give rise to liability under Section 1981.

See Goodman, 580 F. Supp. at 1160 (holding the unions liable

after noting that if racial animus is properly inferable there is

liability under Section 1981). The District Court summed it up:

“A union which intentionally avoids asserting dis

crimination claims, either so as not to antagonize the

employer and thus improve its chances of success on other

issues, or in deference to the perceived desires of its white

membership, is liable under both Title II [sic] and § 1981,

regardless of whether, as a subjective matter, its leaders

were favorably disposed toward minorities.”

Id. The Court of Appeals affirmed; the necessary implication is

that the findings of the District Court were not clearly er

roneous. See Anderson v. City o f Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564,

566 (1985) (“a District Court’s finding of discriminatory intent

. . . is a factual finding that may be overturned on appeal only if

it is clearly erroneous” ); Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S.

273, 287 (1982) (Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a) does not differentiate

among categories of findings and, therefore, finding of dis

criminatory intent must be clearly erroneous to be overturned).

See generally Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a).

11

II. UNION LIABILITY UNDER SECTION 1981 AND

TITLE VII FOR REFUSAL TO FIGHT EMPLOYER

DISCRIMINATION IS CONSISTENT WITH NATION

AL LABOR RELATIONS POLICIES.

Petitioners and the Solicitor General argue that requiring a

union to take a more active role in the fight against employment

discrimination will somehow undermine the national labor

policies embodied in the National Labor Relations Act

( “NLRA” ). To the contrary, the Title VII and Section 1981

obligations outlined in this case are wholly consistent with one

of the basic principles of the NLRA—the union’s duty of fair

representation of all members.

A. Construing Title VII And Section 1981 To Prohibit A

Union From Discrimination In The Processing Of Mem

bers’ Grievances Is Consistent With The Duty Of Fair

Representation.

This Court has held that a union, as the exclusive bargain

ing agent of the employees, has a duty fairly to represent all

employees in both the negotiation and the enforcement of a

collective-bargaining agreement. See Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S.

171, 177 ( 1967). That duty is breached “when a union’s

conduct toward a member of the collective bargaining unit is

arbitrary, discriminatory, or in bad faith”. Id. at 190. Where

the discrimination constituting a breach of the duty of fair

representation is against one of the groups enumerated in Title

VII, then Title VII is violated as well.

The pattern in the Federal courts has been that at least

where the duty of fair representation is breached by a union’s

failure fairly to represent one of the classes enumerated in

Section 703(c)(1) or (3), then Title VII is also violated. See,

e.g., Macklin, 478 F.2d at 989.10 The interpretation of Title VII

and Section 1981 urged upon the Court would serve as an

10 See generally Note, Union Liability for Employer Dis

crimination, 93 Harv. L. Rev. 702, 719-24 (1980) (decisions holding

unions liable under Title VII for inaction based on facts that would

constitute breach of duty of fair representation).

12

added incentive for unions to adhere to their preexisting

obligations.11

Contrary to contentions made by petitioners and the

United States, respondents herein are not urging this Court to

render a decision that requires a union to commence a Title VII

action every time an employer discriminates against one of its

members. The question here is actually much narrower than

that: Whether a union, which is the sole certified collective

bargaining agent responsible for processing arbitrable griev

ances, may single out and refuse to process meritorious griev

ances when requested to do so by their aggrieved members

simply because those grievances are based upon racial dis

crimination.

The unions’ responsibilities to combat discrimination arise

not only from Title VII but also from a collective-bargaining

agreement that provides that Lukens must maintain a policy of

nondiscrimination toward employees. The unions are obligated

fairly to enforce that agreement, and the nondiscrimination

provision therein. Under the national labor policy that prin

ciple is embodied in the duty of fair representation. Civil rights

policy prohibits a union from discriminating,12 or from causing

an employer to discriminate.13 That policy is embodied in Title

VII and Section 1981.

The purposes of Title VII, Section 1981 and the duty of fair

representation have always been focused on eliminating dis-

11 Although respondents did not assert a claim under the NLRA,

the Court of Appeals held that:

“The district court found that the unions intentionally avoided

asserting claims of discrimination. In doing so, tire unions

violated the duty of fair representation owed to their members.

See Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171 ( 1967); Steele v. Louisville &

Nashville R.R. Co., 323 U.S. 192 (1944); see also, Note, Union

Liability for Employer Discrimination, 93 Harv. L. Rev. 702

(1980).”

Goodman, 111 F.2d at 127 (parallel citations omitted).

12 See Section 703(c)(1); Section 1981.

13 See Section 703(c)(3).

13

crimination. In Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 429-30

(1971), the Court held:

“The objective of Congress in the enactment of Title

VII is plain from the language of the statute. It was to

achieve equality of employment opportunities and remove

barriers that have operated in the past to favor an identi

fiable group of white employees over other employees.”

And just as Title VII and Section 1981 arose out of a

demonstrated need to wipe out the last vestiges of dis

crimination, so too:

“The statutory duty of fair representation was developed

over 20 years ago in a series of cases involving alleged

racial discrimination by unions certified as exclusive

bargaining representatives under the Railway Labor Act

99

Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. at 177 (citing Steele, 323 U.S. at 192

and Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, 323 U.S.

210, 213-14 (1944)). More recently this Court has held that

“national labor policy embodies the principle of nondiscrimina

tion as a matter of highest priority . . . .” Emporium Capwell Co.

v. Western Addition Community Org., 420 U.S. 50, 66 (1975)

(citing Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 47

(1974)). How could Title VII and Section 1981 be offensive to

a doctrine that arose out of the same problems and maintains

the same goal?

B. Requiring A Union To Meet Its Obligations Under Title

VII And Section 1981 Imposes No Excessive Burdens Upon

Unions.

The unions claim that they will face substantial hardships

if forced to prosecute all racial grievances. See Pet. Br. at 44.

This argument fails for three reasons.

First, a union is never required to process all grievances

brought by its members. Cf. Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. at 191

(“ frivolous grievances are ended prior to the most costly and

14

time-consuming step in the grievance procedures” ). Under

Title VII, Section 1981 and the duty of fair representation,

nonmeritorious claims should not be processed.

Second, as noted above, because the unions are already

required by the duty of fair representation to pursue a course of

conduct in compliance with Title VII and Section 1981, few

additional burdens would be placed on the unions’ resources.

Third, the argument is inapplicable to the facts herein.

The District Court found that the unions refused to process

racial grievances for reasons other than lack of their resources.

The District Court held the unions liable because they in

tentionally singled out for nonprocessing discrimination claims

“either so as not to antagonize the employer and thus improve

its chances of success on other issues, or in deference to the

perceived desires of its white membership”. Goodman, 580 F.

Supp. at 1160. Moreover, the unions recognized some of the

claims as meritorious, and processed them; but they refused to

identify the claims as racial grievances. Other claims they

refused to process at all.14 But for the unions’ insistence on

treating known acts of discrimination as isolated, nonracial

events, the pattern of discrimination might have been ended

long ago. As a result of their insistence, there have instead had

to be fourteen years of litigation in the Federal courts.

III. A UNION MAY NOT COMPROMISE RIGHTS SE

CURED BY TITLE VII OR SECTION 1981.

Petitioners contend that their right to refuse to process

meritorious racial grievances stems from the unions’ right to

“determine their own bargaining agendas and their own prior

ities and make their own compromises and agreements”. Pet.

Br. at 37.

In Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 417-18

(1975), this Court held that the elimination of discrimination

14 See discussion regarding probationary employees at footnote

7, supra.

15

had to be part of the union’s agenda, whether the union wanted

it to be or not. This Court stated:

“ If employers faced only the prospect of an injunctive

order, they would have little incentive to shun practices of

dubious legality. It is the reasonably certain prospect of a

backpay award that ‘providejs] the spur or catalyst which

causes employers and unions to self-examine and to self-

evaluate their employment practices and to endeavor to

eliminate, so far as possible, the last vestiges of an

unfortunate and ignominious page in this country’s his

tory.’ ”

Id. at 417-18 (quoting United States v. N. L. Indus., Inc., 479

F.2d 354, 379 (8th Cir. 1973)).

In McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co., A ll U.S. 273

( 1976), two white Teamsters were dismissed for mis

appropriating company property. A third and equally guilty

accomplice, who was black, was not discharged. One of the

discharged employees brought a Title VII action against the

Teamsters Union. The union moved to dismiss on the ground

that “ in representing all the affected employees in their rela

tions with the employer, the union may necessarily have to

compromise by securing retention of only some”. 427 U.S. at

284-85. This Court rejected that argument stating:

“The same reasons which prohibit an employer from

discriminating on the basis of race among the culpable

employees apply equally to the union; and whatever

factors the mechanisms of compromise may legitimately

take into account in mitigating discipline of some employ

ees, under Title VII race may not be among them.”

Id. at 285.

In Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western Addition Community

Org., 420 U.S. 50 ( 1975), this Court discussed the relationship

between the union’s duty to represent the majority and the

16

union’s obligations to prevent discrimination against its

membership:

“ In vesting the representatives of the majority with

this broad power Congress did not, of course, authorize a

tyranny of the majority over minority interests . . . Con

gress implicitly imposed upon it a duty fairly and in good

faith to represent the interests of minorities within the

unit.”

Id. at 64 (citing Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171 and Wallace Corp.

v. NLRB, 323 U.S. 248 (1944)). This Court then acknowl

edged two cases wherein the National Labor Relations Board

imposed upon a union the obligation to take action against

discrimination. See id. (citing Hughes Tool Co., 147 N.L.R.B.

1573 (1964) (failure to process racial grievances in violation of

duty of fair representation is an unfair labor practice) and

Local Union No. 12, United Rubber, Cork, Linoleum & Plastic

Workers o f America v. NLRB, 368 F.2d 12 (5th Cir. 1966)

(Board ordered union to propose in collective-bargaining spe

cific contractual provisions to prohibit racial discrimination),

cert, denied, 389 U.S. 837 (1967)). It makes little sense that

the union would not be liable under Title VII—legislation

enacted to correct the injustice caused by decades of “majority

rule”—for the same conduct that would violate the duty of fair

representation under the NLRA.

The fundamental principle of Emporium is that the union

and not the aggrieved member is the proper party to present

racial discrimination grievances to the employer for arbitration.

Aside from holding that the collective-bargaining agreement

precluded minority factions from going straight to the employ

er, this Court highlighted why the union is the better candidate:

“The collective-bargaining agreement involved here pro

hibited without qualification all manner of invidious dis

crimination and made any claimed violation a grievable

issue. The grievance procedure is directed precisely at

determining whether discrimination has occurred. . . . Nor

17

is there any reason to believe that the processing of

grievances is inherently limited to the correction of individ

ual cases of discrimination.”

Id. at 66 (footnotes omitted). This Court recognized not only

that the union would be more effective than the individual at

processing racial discrimination claims, but also that a united

front is more capable of eliminating overall discrimination.

In Emporium, this Court described the national labor

policy as “ long and consistent adherence to the principle of

exclusive representation tempered by safeguards for the protec

tion of minority interests”. Id. at 65. The effect of Title VII and

Section 1981 of deterring unions from deliberately refusing to

challenge known patterns of discrimination—even though re

quested to do so by aggrieved members—is one of those

safeguards.

IV. DISCRIMINATION CAN BE EFFECTIVELY ELIMI

NATED ONLY IF IT IS EXPOSED.

Petitioners cannot avoid Title VII liability by arguing that

the unions brought claims for wrongs other than discrimination

when presented by members with complaints of discrimination.

Allowing a union repeatedly to classify racial discrimination

claims as nonracial grievances would undermine Title VII’s

purpose of deterring discrimination.

A central purpose of Title VII is to deter discrimination.

See Bibbs v. Block, 778 F.2d 1318, 1324 (8th Cir. 1985) (“ ‘by

proving unlawful discrimination, appellant prevailed on a

significant issue in the litigation’ . . . and thereby vindicated a

major purpose of Title VII, the rooting out and deterrence of

job discrimination” ) (citation omitted); Diaz v. American Tel.

& Tel., 752 F.2d 1356, 1360 (9th Cir. 1985) ( “ [ i ] t is, of course,

true that Title VII was designed to deter and remedy dis

crimination on the basis of group characteristics and to remove

barriers that favor certain groups over others” ); Stamford Bd.

18

o f Educ. v. Stamford Educ. Ass’n, 697 F.2d 70, 73 (2d Cir.

1982) (“public policy goals of Title VII, for example, are to

deter discrimination by reason of sex and to compensate

aggrieved persons for the injuries caused to them by reason of

the discrimination” ) (footnote omitted); Thompson v. Sawyer,

678 F.2d 257, 291 (D.C. Cir. 1982) (“Title VII relief is to be

targeted to deter illegal discrimination and to compensate its

victims” ); Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d 333, 342

( 10th Cir. 1975) (“objects and purposes of Title VII . . . are to

achieve equality of employment opportunity and to deter

discriminatory practices” ).

Courts have explicitly discussed and fashioned Title VII

doctrine in terms of deterrence of future discrimination. See

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. at 417-18; Toney v.

Block, 705 F.2d 1364, 1373 (D.C. Cir. 1983) (employer

required to prove by clear and convincing evidence that there is

no basis for backpay, and employee can get ruling on liability

even where there are no damages) (Tamm, J., concurring in

result); EEOC v. Local 638 . . . Local 28, Sheet Metal Workers’

In t’l Ass’n, 532 F.2d 821, 832 (2d Cir. 1976) (back pay);

Reeder-Baker v. Lincoln N at’l Corp., 649 F. Supp. 647, 663

(N.D. Ind. 1986) (punitive damages); Stephenson v. Simon,

448 F. Supp. 708, 709 (D.D.C. 1978) (attorneys’ fees); Altman

v. Stevens Fashion Fabrics, 441 F. Supp. 1318, 1321 (N.D. Cal.

1977) (individual liability of officers).

Title VII’s utility as a deterrent to discrimination will be

undercut if Title VII claims are regularly characterized merely

as claims for wrongs other than discrimination. Obviously, a

deterrent scheme only works if people know it exists and is

being enforced. Thus, in the context of a Fourth Amendment

exclusionary rule case, this Court has noted that the “concept of

effective deterrence assumes that the police officer knows the

probable consequences of a presumably impermissible course

of conduct”. Nix v. Williams, 467 U.S. 431, 445 (1984)

(quoting United States v. Ceccolini, 435 U.S. 268, 283 (1978)

(Burger, C.J., concurring in judgment)).

19

The foregoing is consistent with the District Court’s state

ments that:

“ [I]t seems obvious that vigorous pursuit of claims of

racial discrimination would have focused attention upon

racial issues and compelled some change in racial attitudes.

The clear preference of both the company and the unions

to avoid addressing racial issues served to perpetuate the

discriminatory environment. In short, the unions’

unwillingness to assert racial discrimination claims as such

rendered the non-discrimination clause in the collective

bargaining agreement a dead letter.”

Goodman, 580 F. Supp. at 1160. The unions’ failure to focus

that attention resulted not only in the perpetuation of Lukens’

discriminatory employment practices, but also in demonstrated

ambivalence and prejudice from class plaintiffs’ white co

workers. 15

Upon submission of the bill that became Title VII to the

Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives, Rep.

Dawson explained the need for deterrent legislation:

“Racial discrimination harms not only the person

against whom it is directed, but also scars the mind and

morals of those who indulge or acquiesce in it. In addition,

the country as a whole is weakened because substantial

numbers of its people are thus deprived of adequate

education, employment, recreation, voting participation,

and other essentials of our national life to which all citizens

ought to contribute to the maximum of their abilities.”

110 Cong. Rec. 2732 (1964).

The facts of this case amply demonstrate the continuing

harm caused by discrimination and the sensitivity of the lower

courts to redress that condition. Before the commencement of

15 “Plaintiffs presented a mass of evidence of individual instances

of racial harassment and/or discriminatory treatment.” Goodman, 580

F. Supp. at 1147. The incidents ranged from obscene statements to

derogatory graffiti to demonstrated Ku Klux Klan activities. See

generally id. at 1147-51.

20

this lawsuit, minority employees were discriminated against by

Lukens, harassed by co-workers and denied assistance from

their union in processing their grievances. Despite the unions’

attempts to secure relief by processing nonracial grievances on

behalf of victims of discrimination, the discrimination and the

harassment continued. Since this lawsuit, Lukens has agreed to

a settlement and the unions have processed significantly more

racial grievances; one must assume that, because of the pend

ency of this action and the relief awarded by the lower courts,

racial harassment at Lukens has subsided.

If the unions had taken earlier action and assisted their

members in fighting discrimination, far less harm would have

visited the class plaintiffs herein. Had the unions acted as

Congress intended they act, discrimination at Lukens could

have been eliminated long ago without the need for fourteen

years of litigation or the involvement of this Court.

21

CONCLUSION

The judgment for the Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit should be affirmed.

Harold R. Tyler

James Robertson

N orman Redlich

Trustees

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A. W inston

R ichard T. Seymour

Lawyers’ Committee For

Civil R ights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

G rover G. Hankins

Joyce H. Knox

N ational Association

F or The Advancement

Of Colored People

4805 Mount Hope Drive

Baltimore, Maryland 21215

(301) 358-8900

Antonia Hernandez

E. R ichard Larson

Theresa Bustillos

Mexican American Legal

Defense And Educational

Fund

634 South Spring Street

Los Angeles, California 90014

(213) 629-2512

Respectfully Submitted,

Robert F. Mullen

Counsel of Record

Stacey E. Elias

Ivan F. Blejec

Brooks R. Burdette

Cravath, Swaine & Moore

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

57th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10005

(212) 422-3000

Joan Bertin

Joan G ibbs

American Civil Liberties

Union F oundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, N.Y. 10036

(212) 944-9800

Judith L. Lichtman

Claudia Withers

Women’s Legal D efense Fund

2000 P Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 887-0364

Attorneys for Amici Curiae