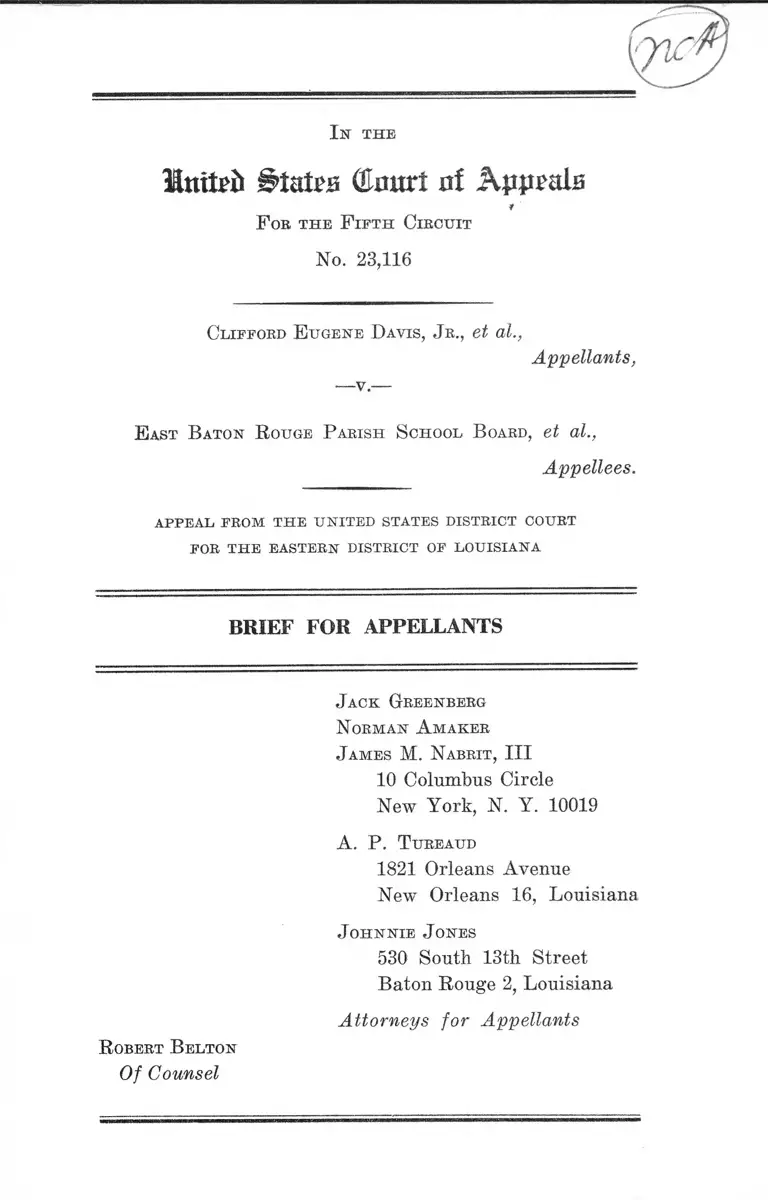

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board Brief for Appellants, 1966. 040d0228-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9b845b8c-0533-4cbf-ac3e-12a975e2a8ba/davis-v-east-baton-rouge-parish-school-board-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I k th e

Ifcuteb States (Enurt nf Appals

*

F oe th e F if t h C ircuit

No, 23,116

Clifford E ugene D avis, J r ., et al.,

Appellants,

—v.—

E ast B aton R ouge P arish S chool B oard, et al.,

Appellees.

appeal from th e united states district court

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

N orman A m aker

J ames M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

A. P. T ureaud

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

J o h n n ie J ones

530 South 13th Street

Baton Rouge 2, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants

R obert B elton

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ...................... - ............................. 1

Proceedings Prior to the Present Appeal ........... 2

Statement of Facts ............................. ............................ 8

Composition of the East Baton Ronge School

System........................................................................... 8

Initial Assignments .................-.................................. 10

Practice Regarding Teachers and Other School

Personnel ...................................................................... 11

School Transportation System ..... 11

The Board’s Practices and Procedures Under

1963 Plan ...................................................................... 12

Specifications of Error ...................................................... 14

A r g u m e n t

I. The Plan Submitted and Approved by the

Court Below Fails to Meet Current Standards 15

A. Current Standards........................................ 15

B. Inadequacy of the Present Plan ............... 16

1. Racial Assignments Are Maintained .... 16

2. The Notice Provision Is Inadequate .... 18

3. The Plan Fails to Provide for Deseg

regated School Transportation ........... 20

4. The Plan Fails to Provide for Faculty

Desegregation

PAGE

21

11

II. Even if the Plan in the Instant Case Meets

All of the Current Standards of a Free Choice

Plan, the Evidence Before This Court Shows

That a Free Choice Plan Is Not Adequate to

Desegregate the Segregated Schools Under

the Jurisdiction of the East Baton Rouge

Parish School Board ........................................... 22

III. The Court Below Erred in Refusing to Con

sider Evidence Which Could Show That a

Freedom of Choice Plan Is Inadequate to

Desegregate the Schools Under the Jurisdic

tion of the East Baton Rouge Parish School

PAGE

B oard...................................................................... 24

Co n c l u s io n ........................................................................................ 27

Certificate of Service......................................................... - 28

T able of C ases

Armstrong v. Board of Education of City of Birming

ham, 333 F.2d 47 (5th Cir. 1964) ............................... 3

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, 306 F.2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962) ...................17,20

Bell v. School Board of Staunton, Va., 249 F. Supp.

249 (W.D. Va. 1966) .............. ........... ..... .................. 23,25

Bradley v. The School Board of Richmond, 345 F.2d

310 (4th Cir. 1965) .............. ........... ....... ................ 15,18,22

Bradley v. The School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S.

103 (1965) ...... .................. ....... ....................................... 21

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) 2, 23, 25

Brown v. County School Board, 245 F. Supp. 549 ____ 17

Buckner v. County School Board, 332 F.2d 452 (4th

Cir. 1964) 18

XU

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F.2d 302 ......................... ....17,26

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ......... -................... - 23

Davis v. Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 214 F.

Supp. 624 (E.D. La. 1963), 219 F. Supp. 876 (E.D.

La. 1963) .......................................................................... 2

Davis v. Board of Commissioners, 333 F.2d 53 (5th

Cir. 1964) ........................................................................ 3

East Baton Rouge County School Board v. Davis,

289 F.2d 380 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied 368 U.S.

831 (1961) ............................................................................ 2

Franklin v. School Board of Giles County, No. 10,214,

4th Cir................................................................................. 21

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) ....... 23

Glynn County Board of Education v. Gibson, 333 F.2d

55 (5th Cir. 1964) ............................................................. 3

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) ...........16, 21

Kier v. County School Board, 249 F. Supp. 239 (W.D.

Va. 1966) ............................................................................ 21

Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County,

342 F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1965) ...................3, 6, 7,17, 20, 24

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education, 345

F.2d 333 (4th Cir. 1965) ...................................... 18

Powell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) ........................................... 21

Price v. Denison Independent School Board, 348 F.2d

1010 (5th Cir. 1965)

PAGE

16

IV

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) .............................. 21

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1963) ................... 25

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ........ ...... 15,16,21,22

Wheeler v. Durham City School Board, 346 F.2d 768

(4th Cir. 1965) ........................................... ................ . 18

PAGE

Oth er A uthorities

General Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, U.S. Department of Health

Education and Welfare, Office of Education, April,

1965 ......-..........................................................................16,18

Revised Statement of Policies for School Desegrega

tion Plans Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, U.S. Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, Office of Education, March 1966 ................... 16

I n th e

llmti'h States (tort a! Appeals

F ob th e F if t h C iectjit

No. 23,116

Clifford E ugene D avis, J k., et al.,

Appellants,

_ v -

E ast B aton R ouge P arish S chool B oard, et al.,

Appellees.

APPE A L FROM T H E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E EASTERN DISTRICT OF LO U ISIAN A

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

Appellants, the plaintiffs below, are appealing from an

order of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Louisiana, entered by Honorable E. Gordon

West on July 15, 1965, approving the defendants present

desegregation plan. This case involves the adequacy of the

present plan for racial desegregation of the public schools

in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana.

2

Proceedings Prior to the Present Appeal

Suit by Negro persons in East Baton Rouge Parish,

Louisiana, was begun in 1956.1

On July 18, 1963, the court below entered an order adopt

ing and approving, with certain modifications, a plan sub

mitted by the defendants pursuant to a previous order.2

Under the plan, all existing school assignments which were

based on race were to remain the same. The School Board

was ordered to mail notices not later than July 19, 1963 to

all students, Negro and white, who would be in the twelfth

grade during the 1963-64 school year advising them that

they could apply for transfer and reassignment to the

twelfth grade of any other school of their choice. The op

tion to transfer had to be exercised during a ten (10) day

period, from July 29, 1963 through August 7, 1963. The

plan specified eight criteria3 the School Board could con

1 On May 25, 1960, an order was entered enjoining the defendant, East

Baton Rouge School Board, from maintaining a segregated school system

and to make necessary arrangements for the admission of all children to

schools under its jurisdiction as required by Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. 294. The order was entered more than four years after the date

on which the complaint was filed. The 1960 order was affirmed by this

Court in 1961 in East Baton Rouge Parish School Board v. Davis, 289

F.2d 380 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied 368 U.S. 831 (1961). On January

22, 1962, no steps having been taken by the School Board to implement

the 1960 district court order, plaintiffs filed a motion for further relief,

which was filed almost eight years after the Brown decision. No attempt

will be made to detail the long series o f legal maneuvers by the School

Board which finally resulted in their submitting a desegregation plan.

Some indication of the background is found in district court opinions in

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, reported at 214 F. Supp.

624 (E.D. La. 1963) and 219 F. Supp. 876 (E.D. La. 1963).

2 The order requiring the School Board to submit a plan is reported in

Davis v. East Baton 'Rouge Parish School Board, 214 F. Supp. 624 (E.D.

La. 1963). The order approving the plan is reported in Davis v. East

Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 214 F. Supp. 624 (E.D. La. 1963).

3 The features which would most impede desegregation by transfer in

cluded the Board being able to consider: (1) the scholastic record,

ability and aptitude of the student desiring transfer in regard to the

sider in granting or denying the transfer. Transfers were

to be made according to procedures currently in general

use by the East Baton Rouge Parish School Board. The

plan had a procedure for administrative review which pro

vided that if a transfer was denied and the parent wished

to make an objection, such objection was to be filed in writ

ing with the Superintendent of Schools by August 27, 1963

and a conference could be requested. Conferences were to

be held between August 27-30, 1963. In the absence of a

request for a conference, it was to be conclusively presumed

that the applicant had no objection to the action taken by

the Board. The order then established a downward progres

sion of desegregation at the rate of one grade per year

and the same administrative procedures mentioned above

were to be followed in subsequent years. The court then

retained jurisdiction for the entire period of transition

(R. 4-9).

On April 19,1965, after the plan had been in operation

for almost two years, the plaintiffs filed two motions: a

motion for further relief and a motion to add additional

parties-defendants. The motion for further relief sought a

modification of the July 18, 1963, order alleging that re

cently decided cases4 requiring the pace of desegregation

to be considerably quickened. The motion also alleged that

the defendants were continuing to maintain and operate

a biracial school system; continuing to maintain and en

force dual school zones based on race; that only a token

school to which transfer was requested; (2) the age of the student; (3) if

space was unavailable at the school to which transfer was desired, after all

students were assigned who had previously been in attendance, the Board

could assign the student to the school nearest his residence (6, 7).

4 E.g., Armstrong v. Board of Education, 333 F.2d 47; Davis v. Board of

Commissioners, 333 F.2d 53 (5th Cir. 1964) ; Glynn County Board of

Education v. Gibson, 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964) and Lockett v. Board

of Education of Muscogee County, 342 F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1955) (R.

13-14).

4

number of students had been allowed to transfer to four

formerly all-white high schools; that one student of su

perior academic achievement was denied admittance to a

white school to which he applied because of an alleged lack

of academic qualifications; that the staff, teachers, and

other supervisory personnel were rigidly separated on

the basis of race; that on or about June 11, 1964, a peti

tion (PI. Exh. 3, R. 33) was filed with the School Board

and Superintendent requesting desegregation of the Board

of Education staff. Notwithstanding the court’s specific

direction that no student need be granted more than one

transfer in any one year, plaintiff’s motion alleged the

School Board allowed such transfers when they oper

ated to resegregate Negro students into Negro schools.

The motion for further relief prayed for the immediate

elimination of all aspects of racial discrimination in the

operation of the East Baton Rouge Parish public schools

including specifically, but not limited to, desegregation of

extra curricular activities; an order to desegregate teacher,

principal and other supervisory personnel; and an order

to completely desegregate all grades in the school system

by the 1965-66 school year by drawing unitary non-racial

geographic zones or attendance areas for all schools in the

system and assigning students to the schools nearest their

respective residences as a matter of right (R. 11-28).

The motion to add additional parties-defendants alleged

that the Baton Rouge citizens Council, Inc., its officers and

members should be added as parties-defendants on the

grounds that the parties sought to be added had circulated

or caused to be circulated a document (PL Exh. 4, R. 38)

among white high school teachers urging them to ostracize

Negro students who availed themselves of the transfer pro

vision and were admitted to formerly all-white schools. The

0

plaintiffs’ motion further alleged that unless the parties-

defendants were added and enjoined they would continue

to attempt to impede the orderly progress of the desegrega

tion (E. 24, 26, 27-28).

On April 23, 1965 the district court caused an order to

show cause to issue to the Baton Rouge Citizens Council

made returnable on June 1, 1965 (R. 39-40). Hearings on

the order to show cause and plaintiffs’ motion for further

relief were held on June 2, 1965.6

At the June 2, 1965 hearing, the Baton Rouge Citizens

Council filed a motion opposing plaintiffs’ motion to add

and in the alternative a motion to dismiss for failure to

state a claim upon which relief could be granted alleging,

inter alia, that the letter complained of was merely advocat

ing theory and included no threat or suggestion of sanction

and was but an expression guaranteed to the defendant by

the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States, and that the acts complained of in no way interfered

with the orderly process of the court (R. 149-152). Also, at

the June 2 hearing, the defendant School Board filed two

motions: (1) a motion to oppose the addition of the Baton

Rouge Citizens Council and its officers and members as im

proper parties-defendants (R. 153) ; and (2) a motion to dis

miss and deny plaintiffs’ motion for further relief. The

School Board’s motion alleged, inter alia, that the plan ap

proved July 18, 1963, and the progress made thereunder

was acceptable to and approved by the great majority of the

citizens of the Parish of East Baton Rouge including, par

ticularly, the great majority of the class represented by the

plaintiffs (R. 154-157).

6 Hearing on the order to show cause and the motion for further relief

was originally set for June 1, 1965 (R. 39, 40, 45).

6

During the hearing on plaintiffs’ motion for further re

lief, the deposition of the Acting Superintendent of Schools

(now Superintendent) was received in evidence (R. 47-

138) and additional oral and documentary evidence was

presented (R. 186-287). The court refused to admit testi

mony of Dr. Donald Mitchell as an expert witness,6 on

whether freedom of choice would be an effective plan of

desegregation.7 8 Plaintiffs also sought to introduce the tes

timony of Negro students who are presently attending for

merly all-white schools that the freedom of choice plan,

either as administered in the past or as administered in

compliance with the rules of the Lockett case and other de

cisions was insufficient to bring about desegregation in the

schools in the East Baton Rouge Parish. The court refused

to admit this evidence (R. 233-242).8 At the conclusion of

6 Dr. Mitchell was, at the time, the Executive Director of the New Eng

land School Development Council. He is a graduate of the University of

New Hampshire with a Master’s Degree in Education. He had analyzed

materials on the East Baton Rouge School System, and had visited the area

for study as a basis for his testimony (R. 252, 262).

7 “ Mr. Bell:

Well, Your Honor, we would like to have him explain in detail,

and in view of this ruling, we would like to proffer his testimony

under the provisions of Rule 42.

“ The Court:

You can proffer it by deposition and file it in the record. I don’t

want someone from Massachusetts coming down to tell the Baton

Rouge school board how to run their schools” (R. 288).

8 “ Mr. Bell:

The second purpose is to show that the experiences of these pupils

in the desegregated schools where they are going with all of this free

dom of choice situation is such that the parents and pupils themselves

are in the main unwilling- to face the same kind of things that these

kids have been asked to face, and therefore—

“ The Court:

This is of no concern at all. We are going to have desegregation

of the schools. I think that the Jewish race has gone through that

from the time of Christ on, they have been subjected to prejudices

7

the hearing, the district court ordered the School Board to

submit a supplemental plan which would include only the

minimum required by Lockett v. Board of Education of

Muscogee County, 343 F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1965) (242-246).

Pursuant to the July 2 order, the defendants on July 9,

1965 submitted its present supplemental plan for desegre

gation. The plan continued the practice of initially assign

ing all students to segregated schools on the basis of race.

In addition to the right of transfer already provided to

Negro students in grades covered under the 1963 plan, a

provision extending the right to transfer to Negro students

in other grades was provided for on the following schedule:

first, second and tenth grades for the 1965-66 school year;

third and fourth grades for the 1966-67 school year; fifth,

sixth and seventh grades for the 1967-68 school year and

the remaining two grades, eighth and ninth, for the 1968-69

school year. Negro students desiring to transfer to all-

white schools, were required to register at the Negro school

in which they were in attendance. Review of the denial of

transfer was to be in accordance with the 1963 plan. With

respect to notifying Negro students and parents of the

right to transfer, the plan provided that:

Due to the time, expense and impracticality involved

in giving written notification to each child within each

district as to the schools available to him, the Board

feels that the best method of notifying all students

concerned of schools available to them, particularly for

the 1965-66 school year, is to notify all principals and

teachers of said districts and to advertise the bounda

and there is no question about it. I think there is a book called the

Wandering Jew that pretty well traces the history of the Jewish

people from the days of Christ to the present time. Unfortunately

those kinds of prejudices can only be erased in a man’s heart; they

cannot be erased by injunction. So we can’t, we can’t do that. . . . ”

8

ries of said districts and the schools available to the

students living therein through the local newspaper,

radio and television communication systems (R. 163).

Then, the Superintendent was directed that “ if . . . [he]

devised a better method of notification with respect to

grades to be desegregated in the future” (R. 163), then he

was authorized to do so. The plan further provided that

transportation of all students in grades affected by the plan

shall be in accordance with the “ laws of the State of Loui

siana and previously adopted policies of the State Board

of Education, the Department of Education and this School

Board” (R. 159-165). On July 15, 1965, the district court

approved the supplemental plan submitted by the School

Board (R. 166-67).

On August 9, 1965, plaintiffs noted an appeal to this

Court from the order of the district court of July 15, 1965,

which approved the plan in issue (R. 167).

Statement o f Facts

Composition of the East Baton Rouge School System

As of May 11, 1965, the East Baton Rouge Parish School

Board had 87 schools under its jurisdiction. Of these,

thirty-three were all-Negro schools which included twenty

six elementary schools, three junior high schools and five

high schools (R. 49). The other 54 schools, 37 elementary

schools, 7 junior high schools and 10 high schools were

attended only by white pupils until the 1963-64 school year

when 28 Negro pupils were admitted to grade 12 in four

formerly all-white high schools (R. 93).

The East Baton Rouge Parish public school system is

divided into approximately 100 school districts under the

9

direction of the School Board and a Superintendent of

Schools. There are separate school district maps for ele

mentary, junior high and high schools. Approximately

70% of the school districts have a racially mixed popula

tion (R. 80, 103). Under the school district arrangement,

boundary lines for a school are established as nearly as pos

sible in an area surrounding the school and takes into con

sideration such factors as school capacity, natural bound

aries, the number of students living in the area and the

possibility of increase or decrease in the population (R,

54, 79, 80, 81). In 1963, the court found that the School

Board maintained separate Negro and white schools and

school districts (R. 66, 74).

As of May 3, 1965, school population was approximately

55,000. Of this number, approximately 33,000 were white

and 22,000 were Negro (R. 70, 71). Thus, Negroes consti

tute approximately 40% of the total school population.

Although there are only approximately 11,000 more white

pupils in the East Baton Rouge public school system than

Negro pupils, 21 more schools have been allotted to white

use than to Negro use. The white school population has a

total of 54 schools whereas the Negro school population

which is 40% of the total, has only 33 schools. Although

40% of the school population is Negro, only 37% of the

school buildings are allotted to Negro pupils, while white

students constituting 60% of the school population occupy

approximately 62% of the schools buildings.

The Superintendent of Schools testified that many of

the schools are overcrowded, he also testified that the Negro

schools are more crowded than white schools (R. 225).

As of May, 1965, the School Board planned to construct

17 additional schools, 11 elementary, 5 junior high and 1

high, to alleviate the problem of overcrowding (R. 130).

10

At present, temporary buildings are constructed when

ever a projection of school population indicates a given

school will be overcrowded for a given school year (R.

68-69). However, the only testimony that any schools were

underutilized came from the Superintendent who said that

at least three white elementary schools and one white high

school were not overcrowded (R. 88).

Initial Assignments

Prior to the 1963-64 school year, the School Board ini

tially assigned every Negro student to a Negro elementary

school and every white student to a white elementary school

(R. 76). Before the first desegregation plan went into ef

fect, school districts for individual elementary, junior high

and high schools were drawn for the particular schools by

the School Board. Separate school districts for the Negro

and white schools were constructed and Negroes were not

free to attend the white schools. Negro students new to

the school system, or graduating from elementary schools

to junior high schools or from junior high schools to high

schools were assigned and were required to register at the

separate Negro school which traditionally served their

areas. Negro students already in the public schools were

assigned to and required to register at Negro junior high

and high schools according to an existing segregated

“ feeder system” (R. 77, 78). Each spring, the files on each

student graduating from elementary school to junior high,

or from junior high to high school was forwarded to the

receiving school and the student was required to register

at the receiving school (R. 105). When a student moved

from one school district to another, he was assigned to a

school in that area which served his race.

11

Practice Regarding Teachers and Other School Personnel

Teachers in the school system must have a teaching certifi

cate duly certified by the State Department of Education

to teach in the subject area. Nothing else is required (R.

122). Teachers coming into the system for the first time

and without prior experience must take the National

Teacher Examination and undergo an evaluative interview

by an appropriate staff member. Every teacher in the sys

tem (except one white teacher) has met the requirements

necessary to teach (R. 123, 124). There are approximately

2,300 teachers, including principals, in the school system,

of which approximately 40% are Negro. The percentage of

Negro teachers roughly corresponds to the percentage of

Negroes in the school system (R, 123). Teachers are as

signed by the School Board. All Negro teachers are as

signed to Negro schools and all white teachers are assigned

to white schools (R. 124). Every white school has a white

principal and every Negro school has a Negro principal.

On the administrative level there are three Negroes in

a supervisory capacity. One Negro is supervisor of all the

Negro elementary schools. The other two Negroes are clas

sified as visiting teachers, whose responsibility is to check

on school attendance; their function is equivalent to truant

officers (R. 125, 126). The Negro administrative personnel

are housed in a building separate and apart from white ad

ministrative personnel (R. 126).

School Transportation System

Students who live more than one mile from the school to

which they are assigned are eligible for transportation to

and from school (R. 136). The East Baton Rouge Parish

School Board has approximately 250 buses which provide

bus transportation for about 25% of the school population

12

on all school levels, and of this percentage 75% of the

busing is provided for elementary school children (R. 129).

However, the school transportation system is segregated.

The School Board maintains separate buses for the trans

portation of Negro and white pupils. Negro drivers trans

port Negro pupils and white drivers transport white pu

pils (R. 129). Negro students who have transferred to

white schools if eligible for school bus transportation, must

ride the Negro buses.

The Board’s Practices and Procedures Under 1963 Plan

Subsequent to the approval of the School Board plan on

July 18, 1963, no formal announcement or written com

munication was sent to the Negro students assigned to the

twelfth grade for the 1963-64 school year advising them

of their right to transfer (R. 92), even though the court

order specifically provided for individual notice to students

(R. 5). Thirty-eight Negroes who had already been as

signed by the School Board to the twelfth grade in four

Negro high schools (R. 93) requested transfers to white

schools. Twenty-eight were admitted to the twelfth grades

of four formerly all-white high schools (R. 102). The ap

plication form, the same form used when a student wanted

to transfer out of his school district, requested the reason

the Negro applicants wished to transfer (R. 95).

In the 1964-65 school year the period of time during

which Negro students could apply for transfer to formerly

all-white schools was reduced from ten to five days. The

principals were called to a meeting and were given a letter

in which they were told to announce to the students of

their respective schools that registration for the 1964-65

school year would be held on April 13-17 and those Negro

students who would be in the 11th and 12th grades could

apply for transfer to the same grades in white schools (R.

13

98). Of 104 Negro students who applied, 99 were allowed

to transfer (R. 98). No reason was given for the five

denials.

At approximately the beginning of the 1964-65 school

year, a letter under the name of the Baton Eouge Citizens

Council, Inc., was circulated among the white high schools

in the school system. White teachers were urged to ostra

cize those Negro students who had been permitted to

transfer to white schools in the grades covered by the

plan (R. 38, 177). This fact was called to the attention

of the Superintendent of Schools and the School Board.

Neither the Superintendent nor anyone connected with the

School Board gave any instructions or had any discussion

with the white high school teachers or principals concern

ing the letter (R. 118). November 20, 1964, Negro students

who had transferred to Glens Oak, a formerly all-white high

school, were segregated from the rest of the white students

in an assembly meeting (R. 118).

For the 1965-66 school year, approximately 103 other

Negro students sought transfer to the 10th, 11th and 12th

grades of formerly all-white high schools. 89 were granted.

Again Negro students in the 9th, 10th and 11th grades

were not given invididual notice as required by the court

order (R. 106). A meeting was held again with the prin

cipals, both Negro and white jointly, and a memorandum

was sent out to the principals of schools having 9th grades

and above in which the principals were requested to advise

all of the students of the date of registration and to advise

Negro students wishing to transfer to white high schools

to fill out preference forms. For the first time since the

plan had been in effect, the transfer form did not request

the reason why the Negro student was requesting the

transfer (R. 106).

14

Specifications of Error

1. The District Court erred in approving a desegrega

tion plan that:

(a) virtually retains intact Negro and white schools;

(b) fails to provide that students new to the school

system must be assigned to schools on a nonracial

basis;

(c) fails to provide for faculty desegregation;

(d) fail to provide for desegregation of the administra

tive staff;

(e) fails to provide for desegregated school bus trans

portation; and

(f) has an adequate notice provision which leaves notifi

cation primarily to the discretion of the school board.

2. The District Court erred in approving a “ freedom of

choice” plan when the evidence shows that the plan is

inadequate to desegregate the public schools in the East

Baton Rouge Parish School system.

3. The District Court erred in refusing to consider

testimony which could show that a freedom of choice plan

is inadequate to desegregate the school system.

15

A R G U M E N T

The Plan Submitted and Approved by the Court Be-

I.

The Plan Submitted and Approved in the Court Be

low Fails to Meet Current Standards.

Although “ freedom of choice” plans for desegregating

public schools have been approved by this Court, there

are minimal judicial standards which must be met before

these plans can merit judicial approval. See Singleton v.

Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 355 F.2d 865

(5th Cir. 1966). The plan in the instant ease, when com

pared with current standards does not merit judicial

approval.

A. Current Standards

In Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865, 876 (5th Cir. 1966), this Court sum

marized the minimum standards as follows:

(1) Desegregation at a speed faster than one grade per

year;

(2) Assignment without regard to race of each pupil

new to the system in grades not reached by the plan;

(3) Simultaneous operation of the plan from both the

high school and elementary end;

(4) Abolition of dual or biracial school attendance areas

contemporaneously with the application of the plan to the

respective grades; and

(5) Admissibility of Negroes to any schools for which

they are otherwise eligible without regard to race.

1 6

In addition to the aforementioned standards, this Court

has also held that faculty desegregation is a necessary

provision of the plan. Moreover, this Court has held that

it attaches great weight to the standards promulgated by

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW )

in determining whether a desegregation plan is acceptable.9

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

supra at 868; Price v. Denison Independent School Board,

348 F.2d 1010, 1012 (5th Cir. 1965). See also Kemp v.

Beasley, 352 F.2d 14, 22 (8th Cir. 1965). Appellants sub

mit that the School Board’s plan failed to meet either the

minimum standards set out by this and other courts or

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

B. Inadequacy of the Present Plan

1. Racial Assignments Are Maintained

The plan in the instant case is not characteristic of free

choice plans as approved in other cases or as adopted by

HEW. This court in setting guidelines for determining if

a free choice plan is to be approved said:

“We approve the use of a freedom of choice plan

provided it is within the limits of the teaching of the

[Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Board of Education, 333

F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964)] and [Gaines v. Dougherty

9 In 1965, as part of the enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, which bars federal funds to racially segregated public schools,

the United States Commissioner of Education promulgated standards for

testing all desegregation plans in terms of their actual performances. See

General Statement of Policies under Title V I of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 Respecting Desegregation of Elementary and Secondary Schools,

United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Office of

Education, April 1965. A revised statement updating the 1965 require

ments was issued by the Commissioner of Education in March 1966. See

Revised Statement of Policies for School Desegregation Plans under Title

VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. United States Department o f Health,

Education and Welfare, Office of Education, March 1966.

17

County Board of Education, 334 F.2d 983 (5th Cir.

1964) ] cases. We emphasize that those cases require

that adequate notice of the plan to be given to the

extent that Negro students are afforded a reasonable

and conscious opportunity to apply for admission to

any school which they are otherwise eligible to attend

without regard to race. Also not to be overlooked is

the rule of Stell that a necessary part of any plan is

a provision that the dual or biraeial school attendance

system, i.e., separate attendance areas, districts or

zones for the races, shall be abolished contemporane

ously with the application of the plan to the respective

grades when and as reached by it. Cf. Augustus v.

Escambia County, . . . And onerous requirements in

making the choice such as are alluded to in Calhoun

v. Latimer, 5 Cir., 1963, 321 F.2d 302, and in Stell

may not be required.” Lockett v. Board of Education

of Muscogee County, 342 F.2d 225, 228-229 (5th Cir.

1965) .

The ideal to which a freedom of choice plan must aspire,

as well as any other desegregation plan, is the end that

school boards will operate “ schools” , not “Negro schools”

or “white schools” . Brown v. County School Board, 245

F. Supp. 549, 560 (W.D. Va. 1965). In other words, free

dom of choice does not mean a choice between a clearly

delineated “Negro school” (having an all-Negro faculty

and staff) and a white school (having an all-white faculty

and staff). School authorities who have operated dual

school systems for Negroes and whites must assume the

duty of eliminating the affects of dualism before a free

dom of choice can be approved.

The plan in the instant case is nothing more than a

scheme which permits the School Board to continue main

18

taining separate Negro and white school, with a “theo

retical” provision allowing Negro students to transfer to

schools where they can obtain a desegregated education.

Appellants submit that an alleged freedom of choice plan

which continues assignment of Negro pupils on the same

racial basis used when segregation was compelled by state

law is insufficient when proffered and approved as com

pliance with a school board’s affirmative obligation to es

tablish a desegregated school system. Wheeler v. Durham

City School Board, 346 F. 2d 768, 772 (4th Cir. 1965);

Bradley v. School Board, 345 F.2d 310, 319 (4th Cir. 1965);

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education, 345 F.2d

333, 334 (4th Cir. 1965).10 See Buchner v. County School

Board, 332 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964).

2. The Notice Provision Is Inadequate

The notice provision in the School Board’s plan pro

vides :

Section I V : Due to the time, expense and imprac

ticability involved in giving written notification to

each child within each district as to the schools avail

able to him, the Board feels that the best method of

10 “ A system of free transfer is an acceptable device for achieving a

legal desegregation of schools. . . . In this circuit, we do require the

elimination of discrimination from initial assignment as a condition of

approval of a free transfer plan.” Bradley v. School Board, supra, 318-

319. “As we pointed out . . . freedom of transfer out of a segregated

system is not a sufficient corrective in this Circuit. It must be accom

panied by an elimination of discrimination in handling initial assign

ment.” Nesbit v. Statesville School Board, supra, at 334.

The 1965 H.E.W. guidelines clearly provide that in a freedom of

choice plan, if no choice is made, Negro students shall be assigned to the

school nearest their homes or on a basis of nonracial attendance zones.

Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Respecting Desegregation of Elementary and Secondary Schools, (V,D,

3(c) ) , Office of Education, Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

19

notifying all students concerned of the schools avail

able to them, particularly for the 1965-66 school year,

is to notify all school principals and teachers of said

districts and to advertise the boundaries of said dis

tricts and the schools available to the students living

therein through the local newspaper, radio and tele

vision, communication systems. In accordance with

this view, the superintendent is hereby directed to es

tablish a day for the registration of students and to

immediately proceed with advertising such districts

and available schools through the newspaper, radio

and television systems allowing for at least a thirty

day period between the first publication of the new

districts and the date of registration in order to give

as much notice as possible to the students and parents

affected hereby (R. 163).

The notice provision in the instant plan is similar to the

plan approved by the District Court in 1963 (R. 7). How

ever, in the 1963 plan the notice provision required the

School Board to mail notice to all students in the grades

affected (R. 7). The evidence shows that the School Board

did not, in fact, mail individual notices to the students,

but rather the only notice given Negro students for the

1963-64 school year was by means of announcement in the

newspaper (R. 92-93). In the 1964-65 school year the

School Board held a separate meeting with the principals

of the Negro high schools. They were told to advise Negro

students at their respective schools, who wished to avail

themselves of the transfer provision of the 1963 plan, that

they would have to register on certain specified dates (R.

98-99). Again, in 1965, the School Board failed to give

individual notices to students (R. 98). The Superintend

ent of Schools testified that he did not know whether the

20

principals did in fact give notice to the students and made

no attempt to determine whether notice was in fact given

(E. 196). These facts demonstrate that although the School

Board was required by court order to give individual

notices to Negro students the order was disobeyed. Fur

ther, the haphazard methods used by the School Board

under the 1963 plan indicate an intent to circumvent the

desegregation plan.

The notice provision in the present plan does not contain

an order specifying that the School Board must give indi

vidual notice to Negro students. It leaves the mechanics

of notice to the discretion of the School Board. Consider

ing the Board’s earlier disregard for court-imposed notice

requirements, one can hardly expect that it will exercise

the discretion granted under the 1965 plan in any way but

to frustrate the process of desegregation. The notice pro

vision in the present plan cannot stand and the School

Board must be ordered to adopt a notice procedure which

will give timely notice in such terms and manner which

will bring home to Negro students the rights to be

accorded them. See Lockett v. Board of Education of

Muscogee County, supra at 229; Augustus v. Board of

Public Instruction of Escambia County, 306 F.2d 862 (5th

Cir. 1962).

3. The Plan Fails to Provide for Desegregated

School Transportation

The provision in the plan relating to bus transportation

provides:

Section V II: Transportation of students in the

grades and to the schools affected hereby shall be in

accordance with the laws of the State of Louisiana

and previously adopted policies of the State Board of

21

Education, Department of Education, and this School

Board and shall he provided, or not provided, as the

case may be, again without regard to race or color

(R. 164).

The record indicates that during the two-year operation

of the 1963 plan, Negro students who transferred to for

merly all-white schools were required to ride segregated

Negro buses to and from white schools (R, 129). The

present plan does not go far enough in ordering the School

Board to desegregate school transportation. As the order

now stands, it allows the School Board to continue to

segregate Negro students who are now in white high

schools. This result defeats the purpose of the desegrega

tion order.

4. The Plan Fails to Provide for Faculty Desegregation

The evidence shows that the School Board is continuing

its discriminatory practice of assigning only Negro teach

ers to all-Negro schools and assigning only white teachers

to all-white schools (R. 124). This Court, after reviewing

the Supreme Court decisions in Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S.

198 (1965) and Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382

U.S. 103 (1965), has concluded that school boards must

now include specific plans for faculty and staff desegrega

tion. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, supra at 870. In accord with Singleton, supra, are

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14, 22-23 (8th Cir. 1965); Kier

v. County School Board, 249 F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Ya. 1966);

and Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965). Cf. Franklin v. School Board of

Giles County, No. 10,214, 4th Cir. April 6, 1966.

22

II.

Even if the Plan in the Instant Case Meets All of the

Current Standards of a Free Choice Plan, the Evidence

Before This Court Shows That a Free Choice Plan Is

Not Adequate to Desegregate the Segregated Schools

Under the Jurisdiction of the East Baton Rouge Parish

School Board.

An acceptable freedom of choice plan, is at best, only

an allowable interim measure a school board may use in

fulfilling its obligation to desegregate the school system.

See e.g., Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 355 F.2d 865, 871 (5th Cir. 1966); Bradley v.

School Board, 345 F.2d at 324 (opinion of Justices Sobeloff

and Bell concurring in part, dissenting in part). The

test of whether a freedom of choice plan is acceptable

as an interim measure is, among other things, the at

titude and purpose of (1) public officials in setting

up the plan, (2) school administrators and faculty in ad

ministering the plan and (3) the effectiveness of such a

plan in disestablishing the segregated school system in a

particular community.11

The evidence clearly establishes the existence of tra

ditional patterns of initially assigning pupils by race on

the basis of separate school districts for Negroes and

whites, even though the court has ordered desegregation

and approved a plan. Paper compliance and policy state

ments are insufficient to satisfy the affirmative obligation

of a school board to desegregate its school system as re

11 “ Affirmative action means more than telling those who have been

deprived of freedom of educational opportunity ‘You have a choice.’ In

many instances the choice will not be meaningful unless the administrators

are willing to bestow extra effort and expense to bring the deprived pupils

up to the level where they can avail themselves of the choice in fact as

well as theory.” Bradley v. School Board, supra at 323.

23

quired by the second Brown decision. See Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 7-8 (1958) and Goss v. Board of Educa

tion, 373 U.S. 683 (1963). These cases make it perfectly

clear that where assignments and transfer policies based

solely on race are insufficient to bring about more than a

token change in a segregated system, the board must devise

affirmative action reasonably appropriate to effectuate

the desegregation goal. As of May 1965, there were 87

schools, including elementary, junior high and high school

under the jurisdiction of the School Board. Thirty-three

of these schools were all-Negro and 54 were all-white,

serving a total school population of more than 55,000 stu

dents. Since the order requiring the School Board to

desegregate the schools only 245 Negro children have ap

plied for transfer, and of this number, only 216 Negro

children were permitted to transfer out of a total number

of more than 33,000 Negro students of school age.

Appellants, in their motion for further relief, moved for

a desegregation plan under which the School Board would

be ordered to construct a single system of geographic at

tendance zones. Under appellants’ proffered plan, Negro

and white pupils living within the newly constructed zones

would be assigned to schools based on a non-racial basis.

Appellants’ proposed plan has been held to be an accept

able desegregation plan. See e.g., Bell v. School Board of

Staunton, Va., 249 F. Supp. 249 (W.D. Va. 1966).

Appellants, in this Court, adhere to their argument that

nonracial assignments by zones is the only means of obtain

ing lawful desegregation in the East Baton Rouge Parish

school system.

24

III.

The Court Below Erred in Refusing to Consider Evi

dence Which Could Show That a Freedom of Choice

Plan Is Inadequate to Desegregate the Schools Under

the Jurisdiction of the East Baton Rouge Parish School

Board.

This appeal involves a question concerning the nature

of the continuing supervision of a district court over ap

proving plans for racial desegregation of public schools

which have been found to be operated on a compulsory

biracial basis.

At the time of the hearing on plaintiffs’ motion for

further relief, a desegregation plan had been in operation

for a period of two years. Only 245 Negro students had

applied for transfers to previously all-white schools out

of a total number of 23,000 Negro students in a total school

population of 55,000. Of these 245, only 226 Negro students

had been permitted to transfer. With these facts before

it, the district court admitted evidence only on this ques

tion: Whether the Board should be required to submit

a plan meeting the minimal standards of Lockett v. Board

of Education of Muscogee County, 342 F.2d 225 (5th Cir.

1965) (R. 207, 242-246). Plaintiffs’ motion for further

relief had not asked for a plan based on the Lockett deci

sion, but instead had requested the substitution of a new

plan for a freedom of choice type plan approved by the dis

trict court in 1963. This Court, nor any other district court,

has ever held that a plan approved for one school board is

the limit to which a school board in another area must

submit. In fact, the contrary has been the ruling of this

and other courts, namely, that a plan approved for one

25

school district may not be sufficient for another school

district in complying with the dictates of the two Brown

decisions. Therefore, since the court below refused to re

ceive evidence beyond the scope of Lockett, we are left with

the holding that “as a matter of law” no school board need

submit a plan different from that of any other school board.

In Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1963), this Court

restated the basic premises of the Brown decision, 349 IT.S.

294 (1955), namely that the burden of complete desegrega

tion is on the defendants and that a plan may be revised

to accomplish full desegregation as quickly as is feasible

in a given situation. The court stated:

We emphasize that at this point, since it is now clear

that even though the 1960 order prescribed a plan in

specific details, this is not the end of the matter. The

district court of necessity retains continuing jurisdic

tion over the cause. That means that it must make

such adaptations from time to time as the existing

developing situation reasonably requires to give final

and effective voice to the constitutional rights of Negro

children.

There is no rule of law that a school board is limited to

accelerating a desegregation plan to what this or other

courts may have approved. See, e.g., Bell v. School Board

of Staunton County, 249 F. Supp. 249 (W.I). Ya. 1966).

The decision of whether or not a desegregation plan

should be approved rests in the sound discretion of the

district court after it has received evidence showing that

the plan will effectively desegregate a school system. That

discretion, however, is not exercised when the court refuses

to receive evidence which would make its decision an in

26

formed one. In Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F.2d 302 (5th Cir.

1963), this Court sustained the district court in its refusal

to speed up a desegregation process by adopting a zone

plan similar to the one requested in plaintiffs’ motion for

further relief. However, the court, found that the district

court had not abused its discretion because:

There was no evidence before the district court from

which an approximation might he made of the amount

of desegregation reasonably to be expected under a

zone plan . . . in short, there was nothing to show the

inadequacy of the present system in comparison” (at

310-311).

This plainly means, that this Court, at the very least,

expects the lower court to receive evidence which shows

that a desegregation plan is inadequate to desegregate a

school system whether or not that plan has been approved

for another school district. The proffered testimony of

Hr. Donald P. Mitchell, which is made part of this record

on appeal, should have been considered by the district court

in determining whether a freedom of choice plan is inade

quate to desegregate the schools and the East Baton Eouge

Parish School District.

To find, as the plaintiffs contend, that the court below

abused its discretion in refusing to consider the proffered

testimony of Dr. Mitchell does not necessarily mean that

this Court must adopt the plan suggested by the plaintiffs

in their motion for further relief. This Court need only

decide one principle: That an alternative desegregation

plan cannot be rejected without consideration of the facts

and circumstances which might permit its acceptance as

the only plan which could effectively desegregate a segre

gated school system.

27

CONCLUSION

W herefore, fo r all the fo re g o in g reasons, appellants

resp ectfu lly subm it that the ord er o f the cou rt below should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

J o h n n ie J ones

530 South 13th Street

Baton Rouge 2, Louisiana

A . P . T ureaud

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants

R obert B elton

of Counsel

28

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that I served a copy of the foregoing

Brief for Appellants upon John F. Ward, Esq., Burton,

Roberts and Ward, 206 Louisiana Avenue, Baton Rouge,

Louisiana, by depositing same in the United States mail,

air mail, postage prepaid, this day of April, 1966.

Attorney for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. n £ ' - " a<*