Milliken v. Bradley Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 2, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Milliken v. Bradley Brief for Petitioners, 1974. aab40dbe-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9b88b00e-8b89-4388-98b1-7d45601f0e43/milliken-v-bradley-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

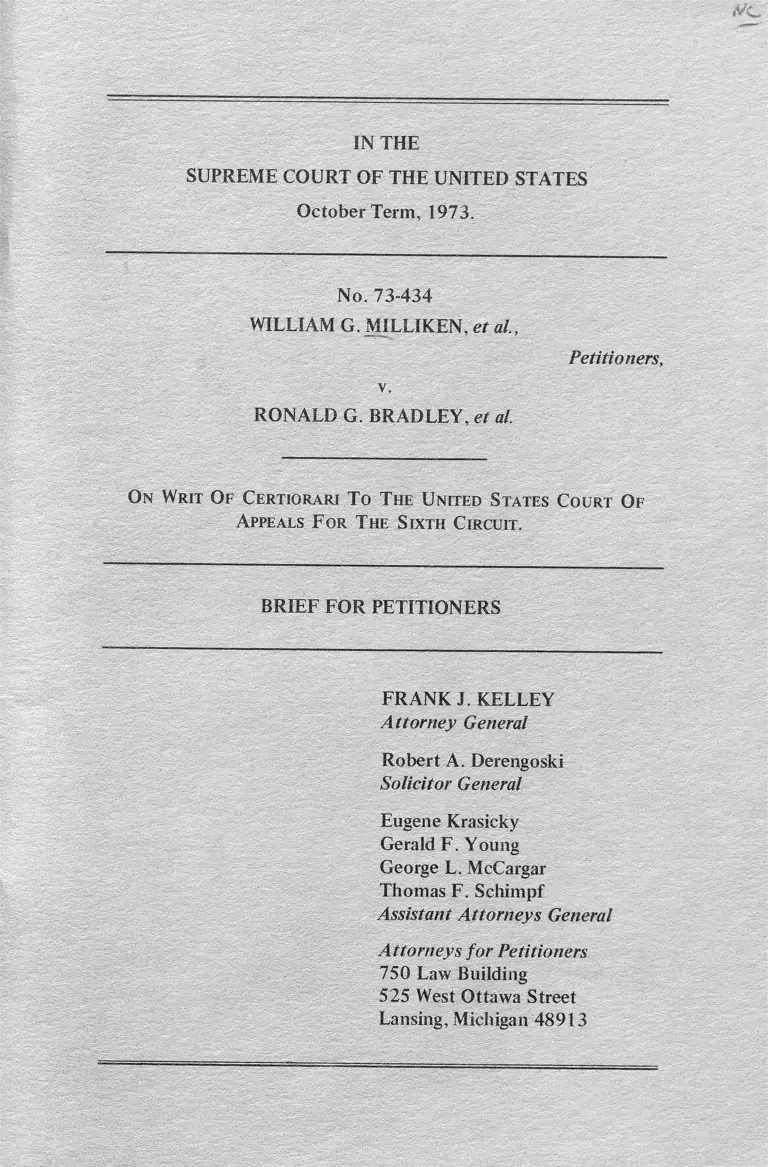

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1973.

No. 73-434

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.

On Writ Of Certiorari T o T he United States C ourt O f

Appeals F or T he S ixth C ircuit.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor General

Eugene Krasicky

Gerald F. Young

George L. McCargar

Thomas F. Schimpf

Assistant Attorneys General

Attorneys for Petitioners

750 Law Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

OPINIONS AND ORDERS BELOW ...................................... 1

JURISDICTION ...................................................................... 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS IN

VOLVED ............................................................................. 3

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ...................................................... 4

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........................... 5

I. The Complaint ........................................................ 6

II. The Detroit Board of Education ............................ 8

III. The State Board of Education and the Super

intendent of Public Instruction .......................... 9

IV. Population — Detroit and the Detroit Board of

Education ............................................................ 9

V. The Tri-County Area of Wayne, Oakland and

Macomb Counties ............................................... 10

VI. Proceedings Through Trial . ..................................... 11

VII. Proceedings After Trial ........................................... 14

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................................ 18

ARGUMENT

I. THE RULING OF THE COURT OF APPEALS

AFFIRMING THE DISTRICT COURT’S HOLD

ING THAT DEFENDANTS MILLIKEN, ET AL,

HAVE COMMITTED ACTS RESULTING IN DE

JURE SEGREGATION OF PUPILS, BOTH

WITHIN THE SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY

OF DETROIT AND BETWEEN DETROIT AND

OTHER SCHOOL DISTRICTS IN A TRI-COUNTY

AREA, IS WITHOUT BASIS IN FACT OR LAW . . 24

11

A. Ruling (5) — transportation of Carver School

Page

District’s high school students ....................... 25

B. Ruling (4) - allocation of transportation funds. 27

C. Ruling (3) — school construction ................... 33

D. Ruling (2) — the effect of section 12 of 1970

PA 4 8 ................................................................ 38

E. Ruling (1) — Detroit Board of Education an

agency of the State of Michigan ..................... 41

II. THE RULING OF THE COURT OF APPEALS

THAT A DETROIT-ONLY DESEGREGATION

PLAN COULD NOT REMEDY THE UNCONSTI

TUTIONAL SEGREGATION FOUND IN THE

DETROIT SCHOOL SYSTEM IS NOT SUP

PORTED BY THE RECORD AND IS CLEARLY

ERRONEOUS AS A MATTER OF LAW. . ........... 46

A. The lower courts rejected the constitutional

concept of a unitary school system within

Detroit for the sociological concept of racial

balance throughout a three-county area.......... 46

B. The teachings of Green, Alexander and Swann

exam ined......................................................... 53

C. The teachings of Green, Alexander and Swann

were unheeded and ignored.............................. 57

D. This Court has consistently required majority

black school systems to convert to unitary

school systems without regard to achieving

racial balance among such majority black

school systems and larger geographical areas . . 58

III. THE DECISION OF THE LOWER COURTS THAT

A MULTI-SCHOOL DISTRICT REMEDY IS CON

STITUTIONALLY PERMISSIBLE HEREIN IS

MANIFESTLY ERRONEOUS.................................. 63

A. Scope of multi-district remedy decreed below

and sought on remand by plaintiffs’ amended

complaint.......................................................... 63

I l l

B. This massive multi-school district relief is not

based upon any constitutional violation in

volving the manipulation of school district

boundaries for purposes of de jure segregation

of pupils between Detroit and the other 85

school districts in the tri-county area............... 64

C. This massive multi-school district remedy is

not supported by any de jure conduct of any

of the school districts to be affected. ........... 67

D. This massive multi-school district remedy is

not supported by any conduct of defendants

Milliken, et al, with the purpose and present

causal effect of segregating children by race as

between Detroit and the other school districts

in the tri-county area. ........................ .............. 68

E. The multi-district relief decreed below is for

the sole purpose of racial balance within a tri

county area....................................... .. 71

F. The attempt by the appellate majority to dis

tinguish Bradley v. Richmond is patently erro

neous. ..................... 78

G. This Court has consistently recognized both

the importance of local control over public

education and the integrity of local political

subdivisions. ........................ 82

H. The multi-district remedy herein will require

excessive expenditures for acquiring, housing,

maintaining and operating school buses to

effectuate racial balance throughout the tri

county area.............................. 85

I. The lower courts denied fundamental due

process to the affected school districts other

than Detroit .................................................... 87

Page

IV. CONCLUSION 89

IV

TABLE OF CITATIONS

CASES P^e

A & N Club v. Great American Insurance Co, 404 F2d 100,

(CA 6, 1968) ...................................................................... .. 13

Airport Community Schools v. State Board o f Education, 17

Mich App 574; 170 NW 2d 193 (1969) .............................. 80

Alexander v. Holmes County Board o f Education, 396 US

19; 90 S Ct 29; 24 L Ed 2d 19 (1 9 6 9 )........ 20 ,21 ,47 ,51 ,53 ,

55, 57, 62, 68

Allen v. Mississippi Commission o f Law Enforcement, 424

F2d 285 (CA 5, 1970).......................................................... 39

Attorney General, ex rel Kies v. Lowrey, 131 Mich 639; 92

NW 289 (1902), a ff’d 199 US 233, 26 S Ct 27; 50 L Ed

167 (1905) .......................................................................... 43

Baker v. Carr, 369 US 186; 82 S Ct 691; 7 L Ed 2d 663

(1962) ............................... 36

Beech Grove Investment Company v. Civil Rights Commis

sion, 380, Mich 405; 157 NW 2d 213 (1968)...................... 46

Blissfield Community Schools District v. Strech, 346 Mich

186; 77 NW 2d 785 (1956) ................................................. 34

Board o f Education o f City o f Detroit v. Lacroix, 239 Mich

46; 214 NW 239 (1927) ..................................................... 34

Bradley v. Milliken, 338 F Supp 582 (ED Mich 1971)........... 1

Bradley Milliken, 345 F Supp 914 (ED Mich 1 9 7 2 )........... 2

Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F2d 897 (CA 6, 1970) 2, 1 1, 38, 39, 40,

41, 69

Bradley v. Milliken, 438 F2d 945 (CA 6, 1971) .............2, 12, 41

Bradley v. Milliken, 468 F2d 902 (CA 6, 1972), cert den 409

US 844 (1972) .....................................................................2,14

Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F 2d 215 (1973)................................ 1

Bradley v. School Board o f Richmond, Virginia, 462 F2d

1058 (CA 4, 1972), aff’d by equally divided Court in

___US___; 94 SCt 31; 38 L Ed 2d 132 (1973) ___ 22,23,61

78, 80, 81,82

V

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 US 483; 74 S Ct 686; 98

LEd 873 (1954) .............................................................. 25, 89

Cleaver v Board o f Education o f City o f Detroit, 263 Mich

301; 248 NW 629 (1933) ................................................... 34

Cotton v Scotland Neck City Board o f Education, 407 US

484; 92 S Ct 2214; 33 L Ed 2 75 (1 9 7 2 )......................... 22, 59

Ford Motor Co v Department o f Treasury o f Indiana, 323 US

459; 65 S Ct 347; 89 L Ed 389 (1945) .......................... 42, 45

Gentry v Howard, 288 F Supp 495 (ED Tenn, 1969) ........... 36

Gomillion v Lightfoot, 364 US 339; 81 S Ct 125; 5 L Ed 2d

110(1960) .............................. ............................................ 66

Goss v Board o f Education o f City o f Knoxville, 340 F Supp

711 (ED Tenn, 1972) ....................... ................................. 62

Goss v Board o f Education o f City o f Knoxville, 482 F2d

1044 (CA 6, 1973) ............................................................ 62

Green v School Board o f New Kent County, 391 US 430; 88

SCt 1689; 20 LEd 2d 716 (1968) . 20 ,21 ,46 ,47 ,51 ,53 ,54 ,

55 ,57 ,60 ,62 ,68

Griffin v County School Board o f Prince Edward County,

377 US 218; 84 SCt 1226; 12 L Ed 2d 256 (1964) ___ 42,55

Hadley v Junior College District o f Metropolitan Kansas City,

397 US 50; 90 SCt 791; 25 LEd 2d 45 (1970) ............... 40

Hiers v Detroit Superintendent o f Schools, 376 Mich 225;

136 NW 2d 10 (1965) ........................................... 34,39,43,81

Higgins v Board o f Education o f the City o f Grand Rapids,

Michigan, (WD, Mich. CA 6386), Slip Opinion, July 18,

1973 ............................................................................... 31,82

In re State o f New York, 256 US 490; 41 S Ct 588; 65 L Ed

1057 (1921) ...................................... 19,42,45

Jones v Grand Ledge Public Schools, 349 Mich 1; 84 NW 2d

327 (1957) ......................................................................... 25,80

Keyes v School District No. 1, Denver Colorado,____US

______ ; 93 S Ct 2686; 37 L Ed 2d 548, (1973) . . 19, 22, 23, 26,

27, 31, 32, 33, 35, 38, 41, 43, 44, 48, 55, 67, 69, 83, 84, 85, 89

Mason v Board o f Education o f the School District o f the

City o f Flint, 6 Mich App 364; 149 NW 2d 239 (1967) . . 82

Page

VI

Munro v Elk Rapids Schools, 383 Mich 661; 178 NW 2d 450

(1970), on reh 385 Mich 618, 189 NW 2d 224 (1971) . . 81

Northcross v Board o f Education o f Memphis, 420 F2d 546

(CA 6, 1969), a ff’d in part and remanded in 397 US 232;

90 S Ct 891; 25 L Ed 2d 246 (1 9 7 0 ).............................. 22,61

Northcross v Board o f Education o f Memphis,___F2d___ ,

No. 73-1667, 73-1954, Slip Op, (1973) . ........................ .. . 61

Barden v Terminal Railway Co, 377 US 184; 84 S Ct 1207;

12 L Ed 2d 233 (1964)................................................... . 42,45

Penn School District No. 7 v Lewis Cass Intermediate School

District Board o f Education, 14 Mich App 109; 165 NW 2d

464,(1968) ............. ............ ...................................... 80,81

Pierce v Society o f Sisters, 268 US 510; 45 S Ct 571; 69 L Ed

1070(1925).................................................................... .. 88

Plessy v Ferguson, 163 US 537; 16 S Ct 1138; 41 L Ed 256

(1896) ................................................................................... 82

Ranjel v City o f Lansing, 417 F2d 321 (CA 6, 1969), cert

den 397 US 980; 90 S Ct 1105; 25 L Ed 2d 390 (1970),

reh den 397 US 1059; 90 S Ct 1352; 25 L Ed 2d 680

(1970) .................................................................... 36

Raney v Board o f Education o f the Gould School District,

391 US443; 88 S Ct 1697; 20 L Ed 2d 727 (1968)___ 22, 60

San Antonio Independent School District v Rodriguez, 411

US 1; 93 SCt 1278; 36 L Ed 2d 16 (1973) . 19, 23, 30, 31, 38,

40, 45, 69,71,83,84, 85

School District o f the City o f Lansing v State Board o f Edu

cation, 367 Mich 591; 116 NW2d 866, (1962)............. 8, 43, 80

Senghas v L ’Anse Creuse Public Schools, 368 Mich 557; 118

NW 2d 975, (1962) .......... 43,81

Smith v North Carolina State Board o f Education, 444 F2d 6

(CA 4, 1971) .............................. 35

Sparrow v Gill, 304 F Supp 86 (MD NC 1969)....................... 31

Spencer v Kugler, 326 F Supp 1235 (D NJ, 1971), a ff’d on

appeal, 404 US 1027; 92 S Ct 707; 30 L Ed 2d 723 (1972). 20,

23, 36, 58, 65, 66

Page

Sterling v Constantin, 287 US 378; 53 S Ct 190; 77 L Ed 375

(1932) ...................................... ....................... .. .................. 19

Swann v Chariotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 402 US

1; 91 SCt 1267; 28 L Ed 2d 554 (1971) .. . 20 ,21 ,22 ,23 ,46 ,

47, 48, 51, 53, 55, 56, 57, 60, 62, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 78, 90

The People, ex rel Workman v Board o f Education o f Detroit,

18 Mich 399 (1 8 6 9 )...............................................................5,82

Tinker v Des Moines Independent School District, 393 US

503; 89 S Ct 733; 21 L Ed 2d 731 (1 9 6 9 )............ .......... .. 44

Wisconsin v Yoder, 406 US 205; 92 S Ct 1526; 32 L Ed 2d

15 (1972) ......................... 88

Wright v Council o f the City o f Emporia, 407 US 451; 92 S

Ct 2196; 33 LEd 2d 51 (1 9 7 2 )___ 22, 23, 40, 59, 71, 72, 82,

83, 85, 88

Wright v Rockefeller, 376 US 52; 84 S Ct 603; 11 L Ed 2d

512(1964) .................................................................. . . . .4 0 ,6 6

Yahr v Resor, 431 F2d 690 (CA 4, 1970) cert den 401 US

982; 91 SCt 1192; 28 L Ed 2d 334 (1971) . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

CONSTITUTIONS AND STATUTES

Constitution of United States

Amendments, Article V ........................................................ 2

Amendments, Article X ............................ .. 3

Amendments, Article XI, ................................................... 3, 19

Amendments, Article XIV, Section 1 ................... .. 3

Federal Statutes

28 USC 1254(1)............................................. 2

FR Civ. P 19 . . . ......................................................................... 64

FR Civ. P 41(b)........................................................................... 13

Michigan Constitution of 1908:

art 1 1, § 2 4, 9

Page

viii

Micliigan Constitution of 1963:

art 4, § 33 . ........................

art 5, § 1 9 .........................

art 5, § 2 9 ..........................

art 5, § 31 ..........................

art 8, § 2 ............................

art 8, § 3 ............................

art 9, § 6 ............................

art 9, § 11 ..........................

art 9, § 1 7 ..........................

art 11, § 2 .........................

. ............. 4, 40, 42

......................4 ,40

..................... 46

...................... 4

. .4, 80, 81, 82, 84

.............4, 6,9, 36

...............4, 30, 87

..................... 4, 30

..................... 4, 42

............... .. . .4, 35

Michigan Public Acts:

1842 PA 70

1937 PA 306 ___

1943 PA 88 ........

1947 PA 336

1949 PA 231 . . . .

1955 PA 269 ___

1957 PA 312 ___

1962 PA 175

1964 PA 289 ___

1965 PA 379

1967 PA 239

1968 PA 112 ___

1968 PA 239 ___

1968 PA 316 ___

1969 PA 2 2 ........

1969 PA 244 ___

........................... 4, 8, 65, 69

........... 4, 34

....................................... 36

....................... .......... .. . 4, 78

........................................4,34

. . .4, 8, 9, 29, 33, 37, 38, 67

78 ,79 ,80 ,81 ,82 ,83 ,84 , 87

................... 4,31,32

........................................ 4, 34

........................................4,81

.............. 4

....................................... 4, 81

...................................... 46

....................................... 4

...................................... 29

........................................ 31

.....................4, 38, 39, 40, 69

IX

Page

1969 PA 306

1970 PA 48

1971 PA 23

1971 PA 171

1972 PA 258

1973 PA 101

............... ................ 4, 36

4, 6, 7, 11, 38, 39, 40, 69

............................ 29,86

................................ 41

................... 4, 30, 32, 86

..........................4, 30, 86

Miscellaneous

Bulletin 1012, Michigan Department of Education,

December, 1970 ............................................................ 26, 28

Michigan Statistical Abstract 1972 (9th Ed.) ...................... 10

Statistical Abstract of United States 1972 (93rd Ed.) . . . . 10

A Description and Evaluation of Section 3 Programs in

Michigan 1969-1970, Michigan D epartm ent of

Education, 1970, Appendix B .................... 31

1

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1973.

No. 73-434.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al„

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.

Petitioners,

O n Writ of C ertiorari to the U nited S tates C ourt of

A ppeals for the S ixth C ircuit

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

OPINIONS AND ORDERS BELOW

The opinions of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

are reported at 484 F2d 215 and are reprinted in the Appendix to

Petitions for Writ of Certiorari at pp 110a-240a, HI

Other opinions delivered in the Courts below are:

United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Michigan, Southern Division

September 27, 1971, Ruling on Issue of Segregation, 338 F

Supp 582. (17a-39a).

November 5, 1971, Order [for submission of Detroit-only

and metropolitan desegregation plans], not reported. (46a-47a).

t i 1 Hereafter, references to appendices, records and exhibits will be enclos

ed in parentheses and indicated as follows:

Single joint appendix: (Ial et seq.)

Appendix of constitutional and statutory provisions: (laa et seq.)

Appendix to petitions for writ of certiorari: (la et seq.)

Record of trial: (R 1 et seq.)

Record of proceedings before or after trial: (Date of proceeding

).

Exhibits: Plaintiffs’ (PX ), defendant Detroit Board of Education’s

(DX ), defendant-intervenor Detroit Federation of Teachers’ (TX

)■

2

March 24, 1972, Ruling on Propriety of Considering a Metro

politan Remedy to Accomplish Desegregation of the Public

Schools of the City of Detroit, not reported. (48a-52a).

March 28, 1972, Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on

Detroit-Only Plans of Desegregation, not reported. (53a-58a).

June 14, 1972, Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order for

Development of Plan, and Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law in Support of Ruling on Desegregation Area and Develop

ment of Plan, 345 F Supp 914. (59a-105a).

July 11, 1972, Order for Acquisition of Transportation, not

reported. (106a-l 07a).

September 6, 1973, Order [granting plaintiffs’ motion to join

all school districts in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb Counties, ex

cept the Pontiac school district], not reported. (Ia 300-1 a 301).

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

July 20, 1972, Order [granting leave to appeal], not report

ed. (108a-109a).

Other opinions of the Court of Appeals rendered at prior

stages of the present proceedings are reported in 433 F2d 897,

438 F2d 945 and 468 F2d 902, cert den, 409 US 844 (1972).

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on June

12, 1973. (241a, 244a-245a). The petition for certiorari was filed

on September 6, 1973, and was granted on November 19, 1973.

The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 USC 1254 (1).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

United States Constitution:

Amendments, Article V - “No person shall be held to answer

for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a present

ment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the

3

land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in

time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for

the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor

shall be compelled in any Criminal Case to be a witness against

himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due

process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use,

without just compensation.”

Amendments, Article X — “The powers not delegated to the

United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the

States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

A m endm ents, Article XI — “The Judicial power of the

United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law

or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United

States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of

any Foreign State.”

Amendments, Article XIV, Section 1 — “All persons bom or

naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction

thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein

they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall

abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United

States; nor shall any State deprive any person or life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Due to the voluminous number of Michigan constitutional

provisions and statutes cited in their brief, defendants, Milliken, et

al, have compiled an appendix to their brief, pursuant to Rule

40.1(c), containing virtually all the Michigan constitutional and

statutory provisions which are cited in their brief. This appendix,

which is referred to herein as (laa et seq.), has been separately

bound since combining the brief and appendix in one volume

would have resulted in too bulky a document for the reader.

Where such appendix has the headings “article,” “part,” “chapter”

or “public act,” it does not necessarily mean that every provision

of that unit appears in the appendix; only those provisions rele

vant to the brief are set forth, including the appropriate section

numbers. The citations to the Michigan constitutional and statu

tory provisions are as follows:

4

Michigan Constitutions

Constitution of 1908, art 1 1, § 2

Constitution of 1963: art 4, § 33; art 5, § § 19 and 31; art 8,

§ § 2 and 3; art 9, I § 6, 11 and 17; art 11, § 2.

Michigan Statutes

1955 PA 269, as amended, (the School Code of 1955); 1842

PA 70; 1969 PA 244; 1970 PA 48; 1964 PA 289; 1967 PA 239;

1937 PA 306, § 1; 1949 PA 231, § 1; 1962 PA 175, § 1; 1968

PA 239, § 1; 1957 PA 312, § 34; 1972 PA 258, § § 18, 21 and

51; 1973 PA 101, §§ 21(1) and 51; 1947PA336, § 15,as added

by 1965 PA 379; 1969 PA 306, § 46, as amended by 1971 PA

171.

When a statute is cited for the first time in this brief, parallel

citations will be given.

The Michigan constitutional provisions and statutes contain

ed in the appendix to this brief have been photocopied from the

two official texts of Michigan laws: The Compiled Laws of 1970

and the Public Acts of the year specified for the law. The sole

exception is 1973 PA 101, which has been copied from the ad

vance sheets to the Michigan Statutes Annotated (MSA), since the

official Public Acts of 1973 have not been published as of this

time. The bold face captions to the constitutional and statutory

provisions are not part of the law of Michigan, but have been sup

plied by the editors of the respective texts for easier reference by

the reader.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I .

Whether, based upon the controlling precedents of this

Court, petitioners, defendants Milliken, et al, have committed acts

of de jure segregation with the purpose and present causal effect

of separating school children by race either within the School Dis

trict of the City of Detroit or between Detroit and other school

districts in the 1,952 square mile tri-county area of Wayne, Oak

land and Macomb?

5

Whether the Detroit School District, a 63.8% black school

district, could operate a unitary system under a Detroit-only dese

gregation plan, thus meeting the remedial requirements of the

Constitution and the decisions of this Court?

II.

III.

Absent any pleaded allegations, any proofs or any findings

either that the boundaries of any of the 86 independent school

districts within the 1,952 square mile tri-county area of Wayne,

Oakland and Macomb have ever been established and maintained

with the purpose and present causal effect of separating children

by race, or that any such school districts, with the sole exception

of Detroit, has ever committed any acts of de jure segregation,

does the Constitution or any decision of this Court permit a

multi-school district remedy?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In this case, the lower courts have used a ruling that the Det

roit school system is de jure segregated as the basis for a remedy

that involves 84 additional school districts in a geographical area

covering approximately 1,952 square miles, and almost Vi of the

public school children in the State, f2 3’ The circumstances and pro

ceedings by which this has come to pass are set forth hereafter.

The separation of the races in the public schools of Michigan

has been prohibited by Michigan law since at least 1869. t4l

[21 Defendants Milliken, et al, realize that while no multi-district desegrega

tion order is in effect at the present time, the District Court’s Ruling on

Desegregation Area and Order for Development of Desegregation Plan (97a)

and the Court of Appeals affirmance thereof in principle (110a) make such a

remedy inevitable unless this Court reaffirms the constitutional principles dis

regarded by the lower Courts in their zeal to achieve a racial balance among

almost 1/2 of the public school children in the State.

[3] petitioners Milliken, Kelley, State Board of Education, Porter and

Green, collectively, will be called “defendants Milliken, et al.” Individual ref

erences will be to that petitioner’s name or office.

[4! The People, ex rel Workman v Board o f Education o f Detroit, 18 Mich

399 (1869).

6

I.

The Complaint

Plaintiffs commenced this class action by filing a complaint

on August 18, 1970. (2a-16a). The complaint was not amended or

supplemented until plaintiffs filed an “Amended Complaint to

Conform to Evidence and Prayer for Relief” on or about Septem

ber 4, 1973. [5] (la 291).

The allegations in plaintiffs’ complaint were limited to claims

of de jure segregation against the defendants solely within the

School District of the City of Detroit. (1 la-12a). Further, plain

tiffs’ prayer for relief was limited to the establishment of a unitary

system of schools within the School District of the City of Det

roit. (13a-15a). In addition, plaintiffs challenged the constitution

ality of § 12 of 1970 PA 48 on the grounds that it interfered with

the implementation of the Detroit Board of Education’s April 7,

1970 plan involving alterations in attendance areas for 12 of the

21 Detroit high schools to increase racial balance in those 12

schools. (13a-15a).

The defendants named in the complaint were William G.

Milliken, Governor of the State of Michigan and ex officio

member (without vote) of the Michigan State Board of Education;

Frank J. Kelley, Attorney General of the State of Michigan; Michi

gan State Board of Education, a constitutional body created by

Mich Const 1963, art 8, § 3; John W. Porter, Superintendent of

Public Instruction of the State of Michigan, ex officio chairman of

the State Board of Education (without vote) and principal execu

tive officer of the Michigan State Department of Education; Board

of Education of the School District of the City of Detroit, a body

corporate under the laws of the State of Michigan; the individual

members of said Board of Education, and the Superintendent of

Schools of said Board of Education. No school district (nor any

officer or employee thereof) other than the School District of the

City of Detroit was named as a defendant.

15] The majority opinion of the Court of Appeals suggested and authorized

the amended complaint. (178a). Plaintiffs made no effort to amend their

complaint prior to the Court of Appeals suggestion.

7

In their original complaint, plaintiffs made three basic claims:

1) that assignment of pupils within the Detroit public schools was

based upon race; 2) that the assignment of personnel within the

Detroit public schools to some extent was based upon race, and 3)

that Section 12 of 1970 PA 48 was unconstitutional because it

interfered with the implementation of the Detroit Board of Educa

tion’s April 7, 1970 plan involving alterations in attendance areas

for 12 of the 21 Detroit high schools to increase racial balance

over a 3 year period in those 12 schools. (2a-13a). The relief sought

was the temporary and permanent enjoining of the effect of Sec

tion 12 of 1970 PA 48 and the requiring that the April 7, 1970

plan be implemented in full in the 1970-71 school year, and

requiring defendants to create and maintain a unitary, nonracial

school system in the Detroit public schools. (13a-15a).

In their pretrial statement (la 75), plaintiffs advanced the fol

lowing claims:

1. That the Detroit public schools were operated in a

manner violating the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States.

2. That the Detroit school system operated racially identifi

able “Negro” and “White” schools, which schools are inherently

unequal and which deny plaintiffs equal educational opportuni

ties.

3. That such a school system has an affirmative duty “ to

remove the racial identifiability of the schools in its system by de

segregating the student body of the individual schools and by as

signing and/or reassigning faculty members to each school in ac

cordance with the system-wide ratio of black and white faculty

members and by planning and making faculty additions in a man

ner which will promote and maintain racially non-identifiable

schools.”

Plaintiffs’ claims in the joint pretrial statement (la 103-la

104) were identical.

In summary, plaintiffs alleged that the Detroit Board of Edu

cation operated a de jure segregated school system and they

prayed as their relief that the Detroit public schools be compelled

8

to operate as a unitary school system. Further, plaintiffs’ prayer

for relief was directed entirely to relief in the Detroit school

system and they made no claim for relief against any other school

system.

II.

The Detroit Board of Education

Michigan school districts are organized and classified as pri

mary, fourth class, third class, second class and first class, depen

ding, essentially, upon the number of children between the ages of

5 and 20 within the district. The School Code of 1955, 1955 PA

269, as amended, §§2, 21, 53, 102, 142 and 182; MCLA 340.2,

340.21, 340.53, 340.102, 340.142 and 340.182; MSA 15.3002,

15.3021, 15.3102, 15.3142 and 15.3182. (6aa, 8aa, 20aa). Detroit

is the only first class school district in the state. The other school

districts involved here are third and fourth class school districts.

The City of Detroit was organized as one school district, as a

body corporate by the name and style of “The board of education

of the City of Detroit” in 1842, f6J and remains a single school

district and a body corporate under the same name today. In other

words, the Detroit Board of Education has existed as an inde

pendent body corporate governmental unit with its geographical

boundaries coterminous with those of the City of Detroit since

1842.

The best way to capsulate the function and powers of the

Detroit Board of Education, or any other school district in the

state, is to say, in the words of the Michigan Supreme Court, that

they are “local state agencies organized with plenary powers to

carry out the delegated functions given it by the legislature.” t7l

With regard to plaintiffs’ claims that the Detroit public

schools are a de jure segregated system, the plenary power to

^ 1 842 Laws of Michigan, No. 70, § §1 and 5. (55aa).

I7! School District o f the City o f Lansing v State Board o f Education, 367

Mich 591, 595; 116 NW2d 866, 868 (1962).

9

locate school sites and construct school buildings, to condemn

land therefor, to hire and assign teachers, and to establish attend

ance areas and assign students thereto has been delegated by the

legislature to the Detroit Board of Education. See the School Code

of 1955, supra, §§192 (condemnation) and 215 (buildings and

sites), § §204, 269 and 569 (teacher hiring and assignment) and

§589 (attendance areas and assignment of students). (32aa, 46aa,

49aa).

III.

The State Board of Education and the

Superintendent of Public Instruction

The State Board of Education and the office of the Superin

tendent of Public Instruction were created anew by the Michigan

Constitution of 1963 (Const 1963), art 8, §3. (3aa). In general,

“ [leadership and general supervision over all public education” is

vested in the State Board of Education. Prior thereto the power of

general supervision was vested in the Superintendent of Public In

struction. Const 1908, art 11, §2. (laa). The present Superinten

dent of Public Instruction is appointed by the State Board of Edu

cation, is the chairman of the board without the right to vote and

is responsible for the execution of its policies. Also, he is the prin

cipal executive officer of a state department of education. Const

1963, art 8, § 3. (4aa).

The testimony of Dr. Porter demonstrates the fact that de

fendants Milliken, Kelley, the State Board of Education, and the

Superintendent of Public Instruction, do not exercise supervisory

authority over the Detroit Board of Education in the hiring or as

signment of teachers, in the establishment of attendance areas, in

the establishment of feeder patterns or in the transportation of

children within the Detroit public schools. (Ilia 35 - Ilia 37).

IV.

Population — Detroit and the Detroit

Board of Education

In 1940, the black population of the City of Detroit was

9.2% (of a total population of 1,623,452). (21a). By 1970, the

10

black population had risen to 43.9% (of a total population of

1,513,601). (21a). As the black population increased, it displaced

the white population. (R367-369). As in the case of all large cities

in the United States, blacks and whites in Detroit tend to live in

separate areas of the city so that residential areas are either pre

dominantly black or predominantly white. (R350-35 1).

In the school year 1960-61, the Detroit Board of Education

enrolled 45.8% black pupils. (21a). By the school year 1970-71,

the entrollment of black pupils in the schools was 63.8%. (21a).

In the school year 1960-61, the Detroit Board of Education

operated 266 schools, eight of which had no white children in at

tendance, 73 of which had no black children in attendance, and

the remainder had both white and black children in varying pro

portions. (22a). In 1970, the Detroit Board of Education operated

319 schools of which 30 had no white pupils in attendance and 11

had no black children in attendance, and the remainder had vary

ing percentages of both black and white children. (22a).

V.

The Tri-County Area of Wayne, Oakland

and Macomb Counties

According to the 1970 census, the population of Michigan is

8,875,083, almost half of which, 4,199,931, resides in the tri

county area of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb. Oakland and Ma

comb Counties abut Wayne County to the north and Oakland

County abuts Macomb County to the west. These counties cover

1,952 square miles. The population of Wayne, Oakland and

Macomb counties is 2,666,751, 907,871 and 625,309, respec

tively. Detroit, the state’s largest city, is located in Wayne County.

In the 1970-71 school year, there were 2,157,449 children

enrolled in the school districts in Michigan. 13.4% of these child

ren were black and 84.8% were white. There are 86 independent,

legally distinct school districts within the tri-county area, having a

l8i Michigan Statistical Abstract, 1972 (9th ed.). This area is approximately

the size of the state of Delaware (2,057 square miles), more than half again

the size of the state of Rhode Island (1,214 square miles) and almost 30 times

the size of the District of Columbia (67 square miles). Statistical Abstract of

United States, 1972 (93rd ed.).

11

total enrollment of approximately 1,000,000 children, approxi

mately 20% of whom are black. (66a).

VI.

Proceedings Through Trial

On September 3, 1970, Denise Magdowski, et al, were per

mitted to intervene as defendants, as parents and representatives

of parents of children attending the Detroit public schools. On

November 4, 1970, Detroit Federation of Teachers, Local 231, the

collective bargaining representative of the Detroit Board of Educa

tion’s teachers, was permitted to intervene as a party defendant.

(Ia2).

Plaintiffs moved for interlocutory injunctive relief to, inter

alia, require the Detroit Board of Education to put into effect its

April 7, 1970 plan to increase racial balance in 12 high schools and

to enjoin the implementation of 1970 PA 48 insofar as it might

interfere with the effectuation of the April 7 plan. Defendants

Milliken and Kelley moved for the dismissal of the suit as to them.

On September 3, 1970, the District Court denied plaintiffs’ re

quest for interlocutory relief and dismissed the action as to de

fendants Milliken and Kelley. (Ia59, Ia62). In denying inter

locutory relief, the District Court did not rule on the constitution

ality of 1970 PA 48. (Id.)

Plaintiffs appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Cir

cuit. The Court of Appeals declared 1970 PA 48, § 12 to be un

constitutional and ordered reinstatement of defendants Milliken

and Kelley as parties, “at least at the present stage of the proceed

ings,” but affirmed the denial of interlocutory relief. 433 F2d

897. Defendants Milliken, et al, did not seek a review of the deci

sion of the Court of Appeals.

Upon remand to the District Court, plaintiffs moved for an

order requiring the immediate implementation of the April 7,

1970 plan. In response to plaintiffs’ motion, the District Court or

dered the Detroit Board of Education to submit a high school at

tendance area plan to the Court consisting of that portion of the

action taken by the Detroit Board of Education on April 7, 1970

1 2

with regard to changing the attendance areas of the 12 high

schools, or an updated version thereof achieving “no less pupil in

tegration.” (Ia69). The Detroit Board of Education submitted two

alternate plans known as “The Campbell Plan” and “The Mac

Donald Plan.” In a ruling dated December 3, 1970, the Court

ruled that the “The MacDonald Plan” was superior and ordered

that it be implemented beginning September, 1971. (Ia88, Ia96).

P la in tiffs , claiming that the alternative plan was con

stitutionally insufficient, sought emergency relief in the Court of

Appeals. Relief was denied and the Court of Appeals ordered the

District Court to set a hearing on the merits forthwith. 438 F2d

945. Because the lower courts declined to order that it be done,

the April 7 plan was never implemented.

Trial on the merits, limited to the issue of segregation within

the Detroit public schools, began on April 6, 1971, and concluded

on July 22, 1971, consuming 41 trial days. ^ Early in the trial,

plaintiffs offered testimony as to housing discrimination within

the City of Detroit (IIa9) and later in the trial with respect to

areas in the counties of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb outside of

the City of Detroit. (IIa69). When such testimony was first offered

it was objected to by the defendants Milliken, et al, and by the

Detroit Board of Education for the reason that such testimony in

volved the acts of other persons not parties to the suit. All testi

mony with regard to discrimination in housing was admitted over

[9 J From time to time during the course of the trial attempts were made by

the plaintiffs and by the defendant-intervenor, Denise Magdowski, et al, to

broaden the scope of the trial to affect, as to possible remedy, school districts

not parties in this cause, located outside of the boundaries of the Detroit

school system. From the remarks of the District Court, it is clear that he also

understood what is patent in the pleadings, that the issue was whether the

Detroit School District was a segregated system qua the Detroit public

schools and not with respect to any other school district within the State of

Michigan. Illustrative comments by the District Court follow:

“Well, 1 don’t know whether fortunately or unfortunately this lawsuit

is limited to the City of Detroit and the school system, so that we’re

only concerned with the city itself and we are not talking about the

metropolitan area.” (Ila41).

“ I hope, Mr. Flannery, that is not a threat because I am having enough

to do with my limited jurisdiction in this case, and 1 am not one for

expanding it.” (Ila44).

However, as the trial progressed, the perception of the District Court changed

in pursuit of a multi-district remedy. (R3537, 4003, 4004; 20a)

13

the continuing objection of the defendants Milliken, et al, and the

Detroit Board of Education. (IIa9-IIalO). There was no testimony

regarding acts of housing discrimination on the part of defendants

Milliken, et al, or of the Detroit Board of Education.

At the close of plaintiffs’ case in chief, defendants Milliken,

et al, moved to dismiss pursuant to FR Civ P 41(b). (lal 17-Ial 18).

The District Court took the motion under advisement and the de

fendants Milliken, et al, elected to rest on their motions to dismiss

and did not participate further in the trial on the merits on the

issues of whether the Detroit School District was a segregated

school system.t10l (IIIa86-IIIa87). The District Court at a later

date denied these motions. (242a).

On June 17, 1971, intervenors Denise Magdowski, et al, filed

a motion to join as defendants all of the school districts ip Wayne,

Oakland and Macomb Counties. (Ial 19-Ia 129). The motion was

heard on July 26, 1971 (R4682), and taken under advisement by

the District Court. (R4709). The motion was never acted upon by

the District Court and later the intervenor withdrew the motion.

On September 27, 1971, the District Court rendered its

ruling on the issue of segregation in which it found that “both the

State o f Michigan and the Detroit Board of Education have com

mitted acts which have been causal factors in the segregated condi

tion of the public schools of the City of Detroit.” (Emphasis ad

ded.) (33a). The de jure segregation found to exist was among the

school buildings within the City of Detroit and not between the

Detroit School District and any other school distri ct in the State

of Michigan. (17a-34a). The Court also found that “ [t] he princi

pal causes undeniably have been population movement and hous

ing patterns, . . .” (33a).

[10] rationale for this position is found in A & N Club v Great

American Insurance Company, 404 F2d 100, 103-104 (CA 6, 1968). If a de

fendant proceeds in the case after making a FR Civ P 41(b) motion, he waives

his right to allege error on the motion’s disposition only in light of the evi

dence introduced up to the point of the motion.

14

VII.

Proceedings After Trial

At a hearing on October 4, 1971, the Court orally ordered

the Detroit Board of Education to submit its plan for deseg

regation of its schools within 60 days and ordered the defendants

Milliken, et al, to submit “a metropolitan plan of desegregation”

within 120 days. (43a). A written order to the same effect was

entered on November 5, 1971. (46a-47a).

An appeal by defendants Milliken, et al, of the District

Court’s ruling on issue of segregation and the order of November

5, 1971 was dismissed for the stated reason that the ruling and

order were not final. 468 F2d 902. Their petition for certiorari for

a review of this dismissal was denied. 409 US 844.

As directed by the Court, plans for desegregation were filed

by the parties, including plaintiff, on or before February 4, 1 972.

Between February 9 and 17, 1972, 43 school districts within the

counties of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb filed motions to inter

vene for the purpose of representing their interests and those of

the parents and children residing in the respective school districts.

(Ia 185, la 190, la 193, la 196). Under date of March 6, 1972, the

District Court notified all counsel that hearings on intra-city plans

would begin at 10 a.m. on March 14, 1972; that recommendations

for “conditions” of intervention be submitted not later than

March 14, 1972; that briefs on propriety of metropolitan remedy

by submitted not later than March 22, 1972, and that, tentatively,

hearings on a metropolitan remedy would commence on March

28, 1972. (Ia 203). The hearings on the intra-district plans

commenced on March 14, 1972. On March 15, 1972 the District

Court allowed the 43 school districts to intervene, but imposed 8

conditions upon the intervention that severely limited their parti

cipation in the proceedings. (Ia 204-la 206). Among the condi

tions imposed were the following:

“ 1. No intervenor will be permitted to assert any claim or

defense previously adjudicated by the court.

“2. No intervenor shall reopen any question or issue which

has previously been decided by the court.” (Ia 206).

15

Although the order allowing intervention stated that the interven

tion was allowed for two principle purposes: “(a) To advise the

Court, by brief, of the legal propriety or impropriety of consider

ing a metropolitan plan” and “(b) To review any plan or plans for

the desegregation of the so-called larger Detroit Metropolitan

Area . . . ” , the Court’s notice to counsel of March 6, 1972 direct

ing that briefs on the propriety of the metropolitan remedy be

submitted not latter than March 22, 1972, was not modified to

provide any additional time for the intervenors to file their briefs

or make their objections. The District Court filed its ruling that a

metropolitan desegregation plan was appropriate on March 24,

1972. (48a).

Hearings on the intra-district plans commenced on March 14,

1972 and concluded on March 21, 1972. Plaintiffs’ expert witness,

Dr. Gordon Foster, testified as follows with regard to the intra

district plan that he prepared for plaintiffs (PX C2, R303, 304,

316):

“Q. I believe you testified you prepared an intra-district de

segregation plan for the City of Richmond?

“A. That’s correct.

“Q. Did the plan that you projected in your opinion meet

the constitutional requirements of the Fourteenth

Amendment?

** *

“A. As I remember the situation, yes, I though that the plan

met the requirements of what we then called a unitary

school system.

“Q. Do you think that the plan that you prepared for the

plaintiffs that is under consideration today, do you think

that meets the constitutional requirements of the Four

teenth Amendment?

“A. I believe that it would in terms of at least the factor of

pupil assignment which is what the plan is primarily

about.”

(IVa 95-IVa 96).

* * *

16

“Q. Dr. Foster, in your opinion, your proposed plan to de

segregate the Detroit School District is a sound educa

tional plan, is that correct?

“A. Yes.

* * *

“Q. Yes, I am going to try to lead you in steps. Secondly, it

would provide for equal treatment of children, would it

not?

I think so, yes. I perceive it as nondiscriminatory in that

regard.

In your opinion this would improve the educational

opportunity of Detroit of the children of Detroit?

Yes.”

(IVa 97-IVa 98).

In accordance with the March 6 notice and its ruling that a

metropolitan desegregation plan was appropriate, the District

Court commenced taking testimony on such plans on March 28,

1972. Later that day, the District Court filed its findings of fact

and conclusions of law on Detroit-only plans of desegregation.

(53a). In essence, the Court’s ruling was that no Detroit-only plan

would result in desegregation because of its majority black student

body.

On June 14, 1962, the District Court filed its ruling on deseg

regation area and order for development of plan of desegregation

(97a) and its finding of fact and conclusions of law in support of

ruling on desegregation area and development of plan. (59a). The

judicially decreed “desegregation area” included 53 school districts

covering approximately 700 square miles within a three county

area, involved 780,000 school children and required that at least

310,000 of them be transported. (72a). Although the District

Court had expressly found no de jure segregation in the faculty in

the Detroit public schools (23a-33a), the Order required faculty

and staff reassignment among the 53 districts. (102a-l 03a).

“A.

“Q.

“A.

17

The findings of fact and conclusions of law in support of the

ruling contained the following initial finding:

“It should be noted that the Court has taken no proofs with

respect to the establishment of the boundaries of the 86 pub

lic school districts in the counties of Wayne, Oakland and

Macomb, nor on the issue of whether, with the exclusion of

the city of Detroit school district, such school districts have

committed acts of de jure segregation.” (59a-60a).

18 of the districts included in the “desegregation area” were not

parties to the litigation when the ruling was made. (59a-60a).

The ruling on desegregation area also appointed a panel of 9

persons, la te r increased to 1 1, and charged it with the

responsibility of preparing and submitting a desegregation plan in

accordance with the provisions of the ruling. (99a).

On July 11, 1972, the District Court, following a recommen

dation of the panel, ordered the Detroit Board of Education to

acquire 295 buses, the contracts for such acquisition to be entered

in to not later than July 13, 1972. (106a-107a). Defendants

Milliken, et al, were Ordered to bear the cost of the acquisition

(106a) and by contemporaneous order, the Court on its own mo

tion ordered Allison Green, Treasurer of the State of Michigan, to

be made a party defendant. (Ia 263).

On July 20, 1972, the District Court, pursuant to oral mo

tions made on July 19, 1972, certified to the Court of Appeals the

issues presented by the five controlling orders or rulings made in

the case to date. (Ia 265-la 266). Defendants Milliken, et al, and

others, petitioned the Court of Appeals for permission to appeal

the controlling orders, which permission was granted by the Court

of Appeals. (108a). In said order, the Court of Appeals stayed the

order for acquisition of transportation, July 11, 1972, and all pro

ceedings with regard to the assignement of children and faculty

within the desegregation area, except planning. (109a).

Permission to intervene was granted by the Court of Appeals

to the Michigan Education Association on August 21, 1972, and

to the Professional Personnel of Van Dyke on July 21, 1973.

18

A panel of the Court of Appeals filed its opinion on Decem

ber 8, 1972. Thereafter, defendants moved for rehearing en banc,

which was granted. Following rehearing, in a 6 to 3 decision, the

Court of Appeals (en banc) in substance affirmed the District

Court’s orders and rulings. (189a-190a).

On August 6, 1973, plaintiffs filed a motion in the District

Court for the joinder of all of the school districts in the counties

of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb that had not already been made

parties herein, with the exception of the Pontiac School District

which is under a U.S. District Court desegregation order in another

proceeding. (la 287).

On September 6, 1973, the District Court ordered the joinder

of all of the school districts in Wayne, Oakland and Macomb

Counties that were not parties to the suit, except the Pontiac

School District. (la 300).

On or about September 4, 1973, plaintiffs filed an amended

complaint to conform to evidence and prayer for relief. (la 291 -

la 299). The thrust of this complaint, as contrasted with the ori

ginal complaint, is that the Detroit School System is a de jure seg

regated system not only within the Detroit public schools but as

between the Detroit public schools and other school districts in

the counties of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb. Plaintiffs are plead

ing a new cause of action for a multi-district remedy but do not

allege that school district boundaries have been created or altered

for segregatory purposes nor do they allege that any of the school

districts other than Detroit have committed acts of de jure segrega

tion. (Ia 294).

Although not stated in so many words in the amended com

plaint, from the listing of the school districts in paragraphs 1 5 and

16 thereof it is apparent that plaintiffs are seeking substantially

the same relief as was ordered by the Court in its ruling on dese

gregation area and order for development of plan.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I Defendants Milliken, et al, have not committed acts of de

jure segregation with the purpose and present causal effect of

separating school children by race either within the Detroit

19

school district or between Detroit and the other 85 school

districts in the tri-county area. Keyes v School District No. 1,

Denver: Colorado, _____ US ___93 S Ct 2686,

2697-2699; 37 L Ed 2d 548, 562-566 (1973).

A. The rulings against the defendants Milliken, et al, are

based, not upon their actual conduct in office, but upon

the judicial goal of achieving racial balance throughout a

large, densely populated area convering three counties.

(41a, 224a)

B. It is the Detroit Board of Education, pursuant to Michi

gan law, and not any of the defendants Milliken, et al,

herein, that selects and acquires school sites, constructs

schools, establishes attendance areas and transports and

assigns pupils to the public schools under its operational

control.

C. The State of Michigan is not a party in this cause. De

fendants Milliken, et al, are not vicariously liable for the

alleged de jure conduct of defendant Detroit Board of

Education. US Const, Am XI. Sterling v Constantin, 287

US 378; 53 S Ct 190; 77 L Ed 375 (1932). reState o f

New York, 256 US 490; 41 S Ct 588; 65 L Ed 1057

(1921). The shifting burden of proof principle set forth

in Keyes, supra, 93 S Ct, at 2697, 2698, is carefully

lim ited to situations involving the same defendant

against whom a finding of de jure segregation is made as

to a substantial portion of the school district in ques

tion.

D. The Carver School District has been a part of the Oak

Park School District since 1960, thus, manifestly negat

ing any present segregatory effect. (169a) Keyes, supra,

93 S Ct, at 2698, 2699.

E. Alleged inter-district disparities in financial resources,

among school districts, including funds for intra-district

transportation, give rise to no constitutional violation.

San Antonio Independent School District v Rodriguez,

411 US 1; 93 SCt 1278; 36 L Ed 2d 16 (1973).

20

F. From and after October 13, 1970, the lack of imple

mentation of the April 7, 1970 racial balance plan af

fecting some of the students in 12 of 21 Detroit high

schools has been the result of the unwillingness of the

Detroit Board of Education and the lower courts herein

to implement such plan.

G. There can be no multi-school district school construc

tion violation by defendants Milliken, et al, for the

reason, inter alia, that in each affected school district

herein, it is the local board of education that selects and

acquires school sites and constructs schools under Michi

gan law, and the trial court expressly stated that it took

no proofs as to whether any school district, other than

Detroit, has committed any acts of de jure segregation.

(59a-60a)

II. A dual school system within a school district must be dis

mantled and converted into a unitary school system within

the school district, so that no pupil is excluded from any

school, directly or indirectly, because of race. Green v School

Board o f New Kent County, 391 US 430; 88 S Ct 1689; 20 L

Ed 2d 716 (1968). Alexander v Holmes County Board of

Education, 396 US 19; 90 S Ct 29; 24 L Ed 2d 19 (1969).

Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 402 US

1; 91 SCt 1267; 28 L Ed 2d 554 (1971).

A. The Detroit School District is not a racially imbalanced

system because of any purposeful action to segregate by

defendants Milliken, et al, or the defendant Detroit

Board of Education. Racial imbalance in the Detroit

school system was caused by housing patterns. The Con

stitution imposes no duty upon school officials to over

come racially imbalanced housing patterns by racially

balancing the schools. Spencer v Kugler, 326 F Supp

1235 (DNJ, 1971), affd on appeal, 404 US 1027; 92 S

Ct 707; 30 L Ed 2d 723 (1972).

B. The racial composition of the pupils of the Detroit

School District is 63.8% black children and 34.8% white

children. (21a).

21

C. Assuming, arguendo, that the Detroit School District is a

dual school system, plaintiffs’ Detroit-Only plan to dis

mantle such dual system would establish a unitary sys

tem as required by Green, supra, 391 US, at 442;

Alexander, supra, 396 US, at 20, and Swann, supra, 402

US, at 23. Plaintiffs’ Detroit-Only plan would eliminate

racially identifiable schools, no child would be excluded

from any school, directly or indirectly because of race

or color, and the plan is educationally sound, as testified

to by Plaintiffs’ expert witness. (IVa95-98).

D. Plaintiffs’ Detroit-Only plan, even though it would ac

complish more desegregation than now obtains in the

school district, was disapproved by the District Court

only because it did not lend itself as a building block for

a multi-district plan spanning a tri-county area, and

would make the Detroit school system more identifiably

black. This action of the Court was error. Green, supra,

391 US, at 442; Alexander, supra, 396 US, at 20; and

Swann, supra, 402 US, at 23.

E. The erroneous decision of the District Court, .affirmed

by the majority of the Court of Appeals, is predicated

upon an unwarranted overriding emphasis on the future

black pupil population of the Detroit School District in

1975, 1980 and 1992, based entirely upon conjecture,

so as to justify the exercise of judicial power to attain

the social goal of racially balancing the public schools

within a 1,952 square mile geographical area.

F. The majority of the Court of Appeals affirmed the deci

sion rejecting plaintiffs’ Detroit-Only plan on the erro

neous premise that anything less than a multi-district

plan encompassing a vast geographical area over three

counties would result in the Detroit School District be

ing an all black school district surrounded by all white

school districts.

G. The decisions of this Court command the dismantling of

dual school systems now in majority black school sys

tems and the establishment of unitary systems within

such districts. Unitary systems have been established

22

within a 66% black, 34% white school district in Wright

v Council o f City o f Emporia, 407 US 451;92SC t

2196; 33 L Ed 2d 51 (1972); within a 77% black, 22%

white and 1% American Indian school district in Cotton

v Scotland Neck City Board o f Education, 407 US 484;

92 S Ct 2214; 33 L Ed 2d 75 (1972); within a 60%

black school district in Raney v Board o f Education o f

the Gould School District, 391 US 443; 88 S Ct 1697;

20 L Ed 2d 727 (1968); and within a 64% black, 36%

white school district in Bradley v School Board o f Rich

mond, Virginia, 462 F2d 1058 (CA 4, 1972), affd by

equally divided Court in __US___ ; 94 S Ct 31; 38 L Ed

2d 132 (1973). A unitary system is capable of being es

tablished within a 57% black, 43% white school district

in Northcrossv Board o f Education, 420 F2d 546 (CA 6,

1969), affd in part and remanded in 397 US 232; 90 S

Ct 891; 25 L Ed 2d 246 (1970).

H. A unitary school system having a racial composition of

63.8% black children and 34.8% white children is not

unconstitutional.

III. The lower courts committed manifest error in decreeing a

multi-school district remedy.

A. Federal judicial power may not be substituted for the

legitimate authority of state and local governments in

public education except on the basis of an unconstitu

tional violation. Swann, supra, 402 US, at 16.

B. Here, there is no unconstitutional violation to serve as a

predicate for judicially imposed multi-district relief. The

record is barren of allegations, proofs and findings either

that school district boundaries were manipulated for un

lawful segregatory ends or that any school district, other

than Detroit, committed any acts of de jure segregation.

(59a-60a) Bradley v Richmond, supra, 462 F 2d, at

1060. Further, there is no causal nexus between any

alleged conduct of the defendants Milliken, et al, and

the distribution of pupils by race between Detroit and

the other 85 school districts in the tri-county area.

23

Keyes, supra, 93 S Ct, at 2698-2699.

C. The Constitution does not require racial balance among

school districts over a three county area. Swann, supra,

402 US, at 24. Emporia, supra, 407 US, at 464, 473.

Further, the historical, rational and racially neutral

coterminous boundaries of the city and school district

of Detroit do not constitute a constitutional violation.

Spencer v Kugler, supra, 326 F Supp, at 1240, 1243, In

addition, there has been no showing in this cause “that

either the school authorities or some other agency of

the State has deliberately attempted to fix or alter

demographic patterns to affect the racial composition of

the schools,” . Swann, supra, 402 US, at 32.

D. The traumatic governmental restructuring of scores of

legally , geographically and politically independent

school districts, implicit in the multi-district relief ap

proved by the lower courts, (104a-105a, 188a-189a) is

directly contrary to the result reached in Bradley v

Richmond, supra.

E. The affected school districts are legally, politically and

geographically separate, identifiable and unrelated units

that facilitate local control and participation in public

education through locally elected boards of education.

Thus, based on its past precedents, this Court should

respect the integrity of these local political subdivisions.

Keyes, supra, 93 S Ct, at 2695; Emporia, supra, 407 US,

at 469 and 478; Rodriguez, supra, 411 US, at 49-50, 54.

F. The multi-million dollar transportation costs involved in

multi-school district relief are excessive and will impose

an additional burden on educational resources.

G. The school districts to be affected herein, other than

Detroit, were denied due process by the lower courts.

(See dissenting opinions of Judge Weick, 205a-212a;

Judge Kent, 230a-238a; and Judge Miller, 239a-240a).

24

ARGUMENT

I.

THE RULING OF THE COURT OF APPEALS AFFIRMING

THE DISTRICT COURT’S HOLDING THAT DEFEN

DANTS MILLIKEN,ET AL,HAVE COMMITTED ACTS RE

SULTING IN DE JURE SEGREGATION OF PUPILS, BOTH

WITHIN THE SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF DET

ROIT AND BETWEEN DETROIT AND OTHER SCHOOL

DISTRICTS IN A TRI-COUNTY AREA, IS WITHOUT

BASIS IN FACT OR LAW.

The decisions of the lower courts herein represent, not a faith

ful adherence to the Constitution and the binding precedents of

this Court, but rather an attempt to use the law as a lever in attain

ing what the lower courts decided is the desirable social goal of

multi-school district racial balance throughout a vast three county

area. This is vividly demonstrated by the trial court’s statement in

a subsequent remedy pre-trial conference, “ [i]n reality, our courts

are called upon, in these school cases, to attain a social goal,

through the educational system, by using law as a lever.” (41a)

The sound dissent of the late Circuit Judge Kent sets forth

the overriding concern of the appellate majority for racial balance

among school districts as follows:

“Through the majority’s opinion runs the thread which holds

it together. That thread is the unwillingness apparent in the

minds of the majority to sanction a black school district

within a city which it concludes will be surrounded by white

suburbs. While the majority does not now state that such a

demographic pattern is inherently unconstitutional, neverthe

less, I am persuaded that those who subscribe to the majority

opinion are convinced, as stated in the slip opinion of the

original panel, ‘big city school systems for blacks surrounded

by suburban school systems for whites cannot represent

equal protection of law.’ While that statement has been re

moved from the opinion of the majority, yet the premise

upon which the statement was obviously based must neces

sarily form the foundation for the conclusions reached in the

majority opinion. It may be that such will become the law,

25

but such a conclusion should not recieve our approval on a

record such as exists in this case.” (224a)

Thus, the underlying premise of both lower courts is the

achievement of what they perceived as the desirable social goal of

racial balance among school districts, rather than the vindication

of constitutional rights to attend a school free from racial dis

crimination by public school authorities. Brown v Board o f Educa

tion, 347 US 483; 74 S Ct 686; 98 L Ed 873 (1954). Viewed

against this background, the defendants Milliken, et al, submit

that the rulings that they had committed acts resulting in de jure

segregation are mere makeweights designed to provide the legal

window dressing for the achievement of multi-school district racial

balance.

The constitutional violations allegedly committed by the de

fendants Milliken, et al, are set forth under the caption of “State

of Michigan.” (15la-152a) The majority opinion of the Court of

Appeals elsewhere acknowledges that the State of Michigan is not

a party to this cause. Thus, these rulings are directed against the

defendants Milliken, et al. (115a). The following review of these

rulings will conclusively demonstrate that the courts below, as to

the defendants Milliken, et al, have erected an edifice of unconsti

tutionality upon a foundation of sand in attempting to further

their paramount goal of multi-school district racial balance.

A. R uling (5 ) — tran sp o rta tio n o f Carver Schoo l D is tric t’s

high schoo l s tu d en ts .

Ruling (5) relates to the transportation, by the Detroit Board

of Education, of high school students from the Carver School Dis

trict, which did not have a high school, to Northern High School

within Detroit during the 195Q’s. (152a, 137a-138a). Here, it must

be observed that under Michigan law no school district has any

legal duty to educate non-resident pupils on a tuition basis. Jones

v Grand Ledge Public Schools, 349 Mich 1; 84 NW 2d 327(1957).

However, the Carver area was adjacent to Detroit and the Detroit

school district voluntarily chose to accept these non-resident

pupils (Va 14). The reason that the student were bussed past

Mumford to Northern was that “Mumford was must more

crowded.” (Va 186).

26

The majority opinion states that such transportation “could

not have taken place without the approval, tacit or express, of the

State Board of Education.” (Emphasis added) (152a) The trial

court’s ruling on this point contains no reference to the State

Board of Education. (96a). The record is barren of any proof that

the State Board of Education possessed any actual knowledge of

the transportation in question, let alone approving same. To the

contrary, the record is clear that when the then Superintendent of

the Detroit Schools “became aware of it” such transportation of

Carver students was discontinued. (Va 186). Since not even the

Superintendent of Schools in Detroit was initially aware of this

bus route affecting his own shcool district, what possible basis can

there be for imputing knowledge of this bus route or the racial

compositions of Mumford and Northern high schools to the State

Board of Education in Lansing, Michigan? The Michigan Depart

ment of Education never collected any racial counts of pupils until

after April, 1966. (See next to last paragraph at PX 174, Va 13).

The reference to the State Board of Education by the Court of

Appeals majority is without any evidentiary support. The require

ment of a finding of segregative purpose enunciated in Keyes,

supra, 93 S Ct, at 2697, cannot be met as to ruling (5) for the

reason that purpose presupposes knowledge of the event in

question, an element which is totally lacking in this cause as to

defendant State Board of Education.

In 1960, the Carver School District, an independent school

district, became disorganized and lost its identity and became a

part of the Oak Park School District by attachment of the County

Board of Education, pursuant to Section 3 of 1955 PA 269, as

amended, being MCLA 340.1 et seq; MSA 15.3001 et seq;herein

after referred to as the School Code of 1955. (169a, 6aa). The Oak

Park school district has a 10.1% black student body and, according

to plaintiffs’ expert witness, the black students currently residing

in the former Carver area attending Oak Park schools are thriving

academically. (PX P.M. 12, Va 113, R 939-R 940, R 996-R 997).

Further, in the 1969-70 school fiscal year, Oak Park had the

highest per pupil expenditures of any Michigan school district.

Bulletin 1012, Michigan Department of Education, December,

1970, pp 26-27.

27

This Court has adopted the sound rule that to establish a con

stitutional violation, there must be a causal relationship between

the act complained of and a present condition of segregation.

Keyes, supra, 93 S Ct, at 2698, 2699. Obviously, the reliance of

the majority herein on the transportation of Carver students, not

parties to this action, prior to 1960 to a Detroit high school fails

to meet this controlling test of present causal nexus in light of the

developments since 1960 involving the attachment of Carver to

Oak Park, the attendance of students residing in the former Carver

area in the largely white Oak Park school district and their good

academic performance as testified to by plaintiffs’ expert witness.

B. Ruling (4 ) — allocation of transportation funds

The District Court’s Ruling on Issue of Segregation in Detroit

contained the following language which was quoted in the

majority opinion of the Court of Appeals.

“ ‘ . . . The State refused, until this session of the legislature,

to provide authorization or funds for the transportation of

pupils within Detroit regardless of their poverty or distance

from the school to which they were assigned, while providing

in many neighboring, mostly white, suburban districts the

full range of state supported transportation. This and other

financial limitations, such as those on bonding and the work

ing of the state aid formula whereby suburban districts were

able to make far larger per pupil expenditures despite less tax

effort, have created and perpetuated systematic educational

inequalities' ” (Emphasis added.) (152a).

This language, which constitutes a major part of the District

Court’s holding against the defendants Milliken, et al, on the

initial question of de jure segregation in Detroit goes, not to the

question of pupil assignment in Detroit, but to the markedly dif

ferent question of inter-district disparities in school finance.

Here, it is instructive to note that the trial court made no

conclusions of discriminatory allocation of funds between pre

dominantly black and predominantly white schools within Detroit

although plaintiffs presented evidence directed at the point and

submitted proposed Findings of Fact on the issue which were not

28

adopted by the trial court. The use of alleged inter-district dis

parities in school resources as a predicate for finding de jure segre

gation as to only black students within Detroit, can only be ex

plained by the trial court’s preoccupation with using law as a lever

to obtain the judicially desired goal of multi-school district racial

balance.

Although quoting the trial court in full as to finance, the ap

pellate majority apparently adopted as its own ruling only the dis

trict court language dealing with transportation funds. (151a,

152a). This reluctance to expressly embrace the state school aid

formula and bonding portions of the trial court’s finance language

is readily understandable since such findings are contrary to the

facts in this cause as demonstrated below:

A. In 1969-70, the last school fiscal year for which data

was available prior to trial herein, of the 84 school dis

tricts operating high schools in the tri-county area

(Wayne, Oakland and Macomb counties), only 33 had a