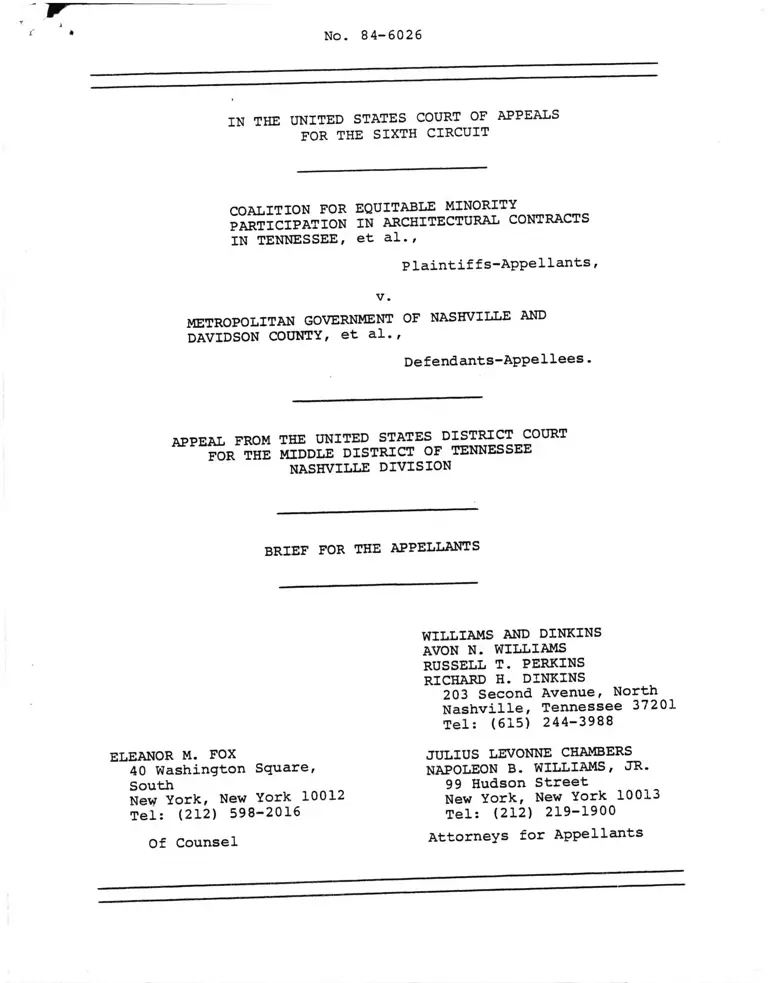

Coalition for Equitable Minority Participation in Architectural Contracts in Tennessee v. Nashville Metropolitan Government Brief for the Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 22, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Coalition for Equitable Minority Participation in Architectural Contracts in Tennessee v. Nashville Metropolitan Government Brief for the Appellants, 1985. f85e34db-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9ba8b0fb-f12d-49a5-b9b2-a7114e16f2c4/coalition-for-equitable-minority-participation-in-architectural-contracts-in-tennessee-v-nashville-metropolitan-government-brief-for-the-appellants. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

No. 84—6026

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

COALITION FOR EQUITABLE MINORITY PARTICIPATION IN ARCHITECTURAL CONTRACTS

IN TENNESSEE, et al.,

— ̂ -I f-f p - Arvr»o 1 1 3 TVt" CJ

V.

METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT OF NASHVILLE AND

DAVIDSON COUNTY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE wic;mrTT,T,E DIVISION

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLANTS

ELEANOR M. FOX40 Washington Square,

SouthNew York, New York 10012

Tel: (212) 598-2016

Of Counsel

WILLIAMS AND DINKINS

AVON N. WILLIAMS

RUSSELL T. PERKINS

RICHARD H. DINKINS203 Second Avenue, North Nashville, Tennessee 37201

Tel: (615) 244-3988

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

99 Hudson StreetNew York, New York 10013

Tel: (212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................. ii

ISSUES PRESENTED ..................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............. 3

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS ............................... 5

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................. 21

ARGUMENT

I. APPELLEES' ANTITRUST DEFENSE IS NOT

A DEFENSE TO APPELLANTS' CIVIL RIGHTS

CLAIMS ...................................... 25

II. CIVIL RIGHTS STATUTES PREEMPT INCONSISTENT

ANTITRUST LAWS AND REQUIRE THE ANTITRUST LAWS

TO BE INTERPRETED AND APPLIED TO CARRY OUT THE

SPIRIT AND THE PURPOSES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS LAWS 32

III. THE COURT SHOULD STRIKE THE ANTITRUST DEFENSE

ON THE GROUND THAT COMPACT IS A PROCOMPETITIVE

JOINT VENTURE AND THAT THE DEFENSE IS WITHOUT

MERIT ...................................... 36

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT SHOULD HAVE APPLIED A

NARROW RULE OF REASON IN VIEW OF CIVIL

RIGHTS LAWS AND POLICIES .................... 46

CONCLUSION ......................................... 48

Page

l

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

A.B. Small Co. v. Lamborn & Co., 267 U.S. 248 (1925) ..... 28

Appalachian Coals v. United States, 288 U.S. 344

(1933) .............................................. 41

Berkey Photo, Inc. v. Eastman Kodak Co., 603 F.2d263 (2d Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 1093

(1980) .............................................. 46

Broadcast Music, Inc. v. CBS, Inc., 441 U.S.

1 (1979) ....................................... 39,40,41

Bruce's Juices, Inc. v. American Can Co., 330 U.S.

743 (1947) ........................................ 28

Brunswick Corp. v. FTC, 456 U.S. 915 ( 1982) ............. 39

Brunswick Corp. v. Pueblo Bowl-O—Mat, Inc., 429 U.S.

477 ( 1977) ......................................... 33

Brunswick Corp. v. Riegel Textile Corp. 1985-1 Trade Cas.

U 66,333 (7th Cir. 1984) 24

California Computer Products, Inc. v. IBM, 613 F.2d

727 (9th Cir. 1979) ................................. 46

Chrysler Corp. v. General Motors Corp., 1985-1 Trade

Cas. 1 66,391 (D.D.C. 1985) ......................... 29

Connoly v. Union Sewer Pipe Co., 184 U.S. 540 (1902) .... 27,28

Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania, Inc., 433

U.S. 36 ( 1977) ..................................... 40'41

Continental Wall Paper Co. v. Louis Voight & Sons Co.,

212 U.S. 227 ( 1909).............................. 26,27,29

D. R. Wilder Mfg. Co. v. Corn Products Ref. Co., 236

U.S. 165 (1915) ................................. 26,28

Eastern Railroad Presidents Conference v. Noerr Motor

Freight, Inc., 365 U.S. 127 ( 1961 ) 21

Gordon v. New York Stock Exchange, 422 U.S. 659

( 1975) ............................................. 33

Hommel Co. v. Ferro Corp., 659 F.2d 340 (3rd Cir.

1981) 46

- ii -

/

Hospital Building Company v. Trustees of Rex Hospital,

1982-83 Trade Cas. 1| 64,992 (4th Cir. 1982), cert,

denied, 104 S.Ct. 231 (1984)........................ 47

Page

Jerrold Electronics Corp. v. United States, 187 F. Supp. 545

(E.D. Pa. 1960), aff'd 365 U.S. 567 91961) ..............

Kalmanovitz v. G. Heileman Brewing Co., 1981-1 Trade Cas.

II 66, 389 (D. Del. 1984) ...........................

Kelly v. Kosuga, 358 U.S. 516 (1959) .................... 2

National Collegiate Athletic Ass'n v. Board of of University of Oklahoma, 104 S.Ct. 2948

(1984) .................................

Regents

.... 38,40,41,42

Pan American World Airways v. United States, 371

U.S. 296 (1963) ..........................

Perma Life Mufflers v. International Parts Corp.,

392 U.S. 134 (1968) .......................

Transamerica Computer Co. v. IBM, 698 F.2d 1377(9th Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 104, S.Ct. 370

(1983) .........................................

Triple M Roofing Corp. v. Tramco, Inc., 1985-1 Trade

Cas. 1966, 382 (2nd Cir. 1985) .................United States v. Addyston Pipe & Steel Co., 85 F. 271

(6th Cir. 1898), aff'd, 175 U.S. 211 (1899) ....

United States v. Arnold, Schwinn & Co., 388 U.S. 365

(1967) .........................................

United States v. Columbia Pictures Corp., 189 F. Supp.

153 (S.D.N.Y. 1960) ............................

United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563 (1966) .

United States v. LTV Corp., 1984-2 Trade Cas. 11 66,133

(D.D.C. 1984) ..................................

United States Motor Vehicle Mfg. Ass'n, 1982-83 Trade

Cas. 11 65,175 ( 1982) ............................

United States v. National Association of Security

Dealers, 422 U.S. 694 (1975) ...................

46

45

39

40

41

44

24

23

33

i n

United States v. Pennington, 381 U.S. 657 (1965) ......... 21

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 110 F.Supp.

295, 347 (D. Mass. 1953), aff'd per curiam, 347

U.S. 521 ( 1954) 37

United States v. Waste Management, Inc., 743 F.2d 976

(2d Cir. 1984) ................................. 24

Yamaha Motor Co. v. FTC, 657 F.2d 979 (8th Cir. 1981), cert, denied sub nom. Brunswick Corp. v. FTC.,

456 U.S. 915 ( 1982) ............................ 39,42

ADMINISTRATIVE CASES

Brunswich Corp., [1979-1983 CCH Transfer Binder]H 21,623 at 21,786 (FTC 1979), aff'd in relevant

part sub nom.................................... 3^

General Motors Corp./Toyota Corp., 48 Fed. Reg. 57246,

57314 ( 1983), 49 Fed. Reg. 18289 ( 1984) ........ 23

In re E. I. duPont de NeMours & Co., 3 Trade Reg. Rep.

1121 ,770 (FTC 1980).............................. 46

Standard Oil Co. of Californiqa, 3 CCHTrade Cas. II 22,144 (FTC 1984) 24

UNITES STATES CONSTITTUION

First Amendment ..................................... 3

Thirteenth Amendment ................................ 3,13

Fourteenth Amendment ................................ 3,13

STATUTES

15 U.S.C. 11 1 2,23,30,20,22,25

15 U.S.C. 11 637(d) ................................ 17,21,29

42 U.S.C. 11 1981

42 U.S.C. 11 1982

Page

42 U . S . C . II 1983

IV

3 . 1 3 . 2 1 . 2 9 . 3 3

3 . 1 3 . 2 1 . 2 9 . 3 3

3 . 1 3 . 2 1 . 2 9 . 3 3

Page

42 U.S.C. 11 1985

42 U.S.C. 11 1986

42 U.S.C.H 1988 .

42 U.S.C. 11 2000d

3.13.21.29.33

3,13,21 ,29,33

3.13.21.29.33

3.13.21.29.33

LEGISATIVE HISTORY

Address by President Wilson on Trusts andMonopolies before Joint Session of Congress

(Jan. 20, 1914) H.R. Doc. No. 625 63rd

Cong., 2d Sess. 5 (1914) .................

Remarks of Senator Kefauver, 96 Cong. Rec.

16452 (1950) ............................

Remarks of Representative Celler, 95 Cong. Rec

11486 (1949) ...........................

Sherman Act, 21 Cong. Rec. 2460 (1890) ......

22

22

22

22

JUSTICE DEPARTMENT GUIDES

Department of Justice Guide on Antitrust andInternational Operations CCH Trade REg. Rep,

No. 266 (Feb. 1 , 1977) ................... .

1984 Department of JusticeMerger Guidelines, 2 CCH

Trade Reg. Rep. 11 4225 ...................... .

1985 Department of Justice Vertical Guidelines, 48 BNA Antitrust &

No. 1199 (Special Supplement,

Restraints

Trade Reg . Rep.

Jan. 24, 1985) .

39

44

44

BOOKS

Areeda, Antitrust Analysis (3rd ed. 1981) ....

Posner, Antitrust Law: An Economic Perspective

(1976) .................................

IV

Page

ARTICLES ' ^

Brodley, "Joint Ventures and Antitrust Policy, 95

Harv. L. Rev. 1523 ( 1982) ...................... 40

Easterbrook, "The Limits of Antitrust", 63

Texas L. Rev. 1 91984) ......................... 24

First, "Competition in the Legal Education Industry,"

53 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 31 1 ( 1978) ..................... 36

54 N.Y.U.L. L. Rev. 1049 (1979) ................. 36

Panel Discussion-Interview with William F. Baxter,

50 A.B.A. Antitrust L. J. 151 (1981) ........... 23

Interview with William F. Baxter, 51 A.B.A. Antitrust

L. J. 23 ( 1982) ................................ 23

- vi -

i

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-6026

COALITION FOR EQUITABLE MINORITY

PARTICIPATION IN ARCHITECTURAL

CONTRACTS IN TENNESSEE, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT OF NASHVILLE AND

DAVIDSON COUNTY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

NASHVILLE DIVISION

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLANTS

ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Whether an agreement among members of appellant

Coalition for Equitable Minority Participation in Architec

tural Contracts in Tennessee hereinafter referred to as

COMPACT not to pursue or accept as an individual firm,

without agreement of all members, any project targeted or

pursued by COMPACT as a potential contract for COMPACT is

an anti—trust violation which operates as a defense to

bar suits alleging racial discrimination in awarding contracts

for architectural services?

2. Whether agreement by members of COMPACT not to

pursue or accept, as individual firms, projects targeted or

pursued by COMPACT as contracts for COMPACT, is a £er se

violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. (1976)?

3. Whether the formation of COMPACT for the purpose of

enabling minority architectural firms to obtain public work

contracts previously denied to them on the basis of race and

inadequate size is a relevant factor for determining the

scope and application of Section 1 of the Sherman Act, and

determining whether the rule of reason ought to be applied

in determining the validity of appellants' acts under the

Sherman Act?

4. Whether the district judge below erred in determin

ing as a matter of law, or as a fact, that minority business

enterprise set-aside shares on public contracts represent a

discrete submarket for architectural services for the

purpose of determining whether appellants' conduct violated

Section 1 of the Sherman Act?

5. Whether the district judge erred in granting summary

judgment against appellants when issues of fact were m

dispute?

6. Did the district judge err in not granting appellant

request below for a preliminary injunction?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Plaintiffs-appellants, a joint venture of three

architectural firms and the members thereof, commenced

this action on August 14, 1984 against the Metropolitan

Government of Nashville and Davidson County, Tennessee,

the Metropolitan Nashville Airport Authority, the

Metropolitan Board of Education, the officers of sard

governmental agencies, and several architectural and

engineering firms, alleging that defendants had maintained

and were pursuing, policies, practices, customs, and usage

of discrimination against plaintiffs as black architects

and architectural firms in Davidson County, Tennessee on

account of their race and color.

The complaint charged that defendants violated

plaintiffs' rights under the First, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States, and under

42 U S C §§1981, 1982, 1983, 1985, 1986, 15 U.S.C. §1 et seq; 42 U.b.c. ss

1988, 2000d. Plaintiffs requested preliminary and final

injunctions enjoining defendants from discriminating against

them on the basis of race or color, and enjoining defendants

to engage COMPACT for architectural services in conjunction

with the design and construction of a new airport facility

in Nashville, Tennessee. The complaint also requested

that plaintiffs be awarded compensatory and punitive damages

The district court, on August 14, 1984 granted a

3

temporary restraining order. A hearing on the temporary

restraining order was held on August 17, 1984 and extended

to August 27, 1984 in conjunction with a hearing on plaintiffs’

motion for a preliminary injunction. On August 27, 1984

the district court dissolved the temporary restraining

order and denied the motion for a preliminary injunction.

Pursuant to a suggestion by the district judge,

appellees, the defendants below, filed on August 27, 1984

a motion for summary judgment. Thereafter, defendants filed

answers to the complaint and the district court, on September

11, 1984 entered an order expediting consideration of the

motion for summary judgment.

On October 18, 1984, the district court filed an

order and accompanying memorandum opinion granting partial

summary judgment against plaintiffs with respect to the claims

involving the construction project at the Metropolitan

Airport and dismissing said claims.

On November 21, 1984, the district court entered an

order, nunc pro tunc October 18, 1984, certifying, pursuant

to Rule 54(b), Fed. R. Civ. P. and 28 U.S.C. §1292(a)(2)

that there is no just reason for delay of an appeal from

the partial summary judgment.

Plaintiffs posted on November 16, 1984, a cost bond

and filed a notice of appeal to this Court.

4 «

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

The plaintiffs-appellants in this action are COMPACT,

three minority architectural firms,^McKissack & McKissack

& Thompson architects & Engineers, Harris Associates

a/k/a Harris S< Harris, Architects, and L. Quincy Jackson,

3/Architect, and individual members of the three minority

architectural firms. COMPACT is a joint venture of the

three firms. The three firms are the only black-owned licensed

architectural firms in middle Tennessee. Jt. Appendix II at 122-23

Prior to 1954, minority architectural firms in middle

Tennessee received awards from municipal, or county, govern

mental agencies, for work on segregated black public projects

such as black schools or black housing projects. Jt. Appendix II,

63, testimony of L. McKissack). No work was provided to

black architects on public projects used for the benefit of

4/

white inhabitants. (Id.).

1/ McKissack & McKissack & Thompson Architects & Engineers

Is the result of a merger in 1984 of two black architectural

firms, McKissack & McKissack and Thompson-Miller, which

previously had been doing business separately for 79 and 12

years respectively. Jt. Appendix I, at 13.

2/ Harris Associates has been in practice for 15 years

In its home office in Nashville, Tennessee. Id. at 14.

3/ l . Quincy Jackson Architect is a single architectural

practitioner, with associates, that has been in practice m

Nashville, Tennessee for over 30 years. Id.

4/ Paragraph 4(b) of the complaint alleges that, when racial

segregation was required by law, the City of Nashville and Davidson County, Tennessee limited "black architects to perform

ing services upon projects intended for the use of black

citizens." Id. at 16.

5

Thereafter, it was the policy of the City of Nashville

and the County of Davidson, Tennessee either to exclude black

architectural firms from work on public projects or to enlist

their services as subcontractors^chosen by a white architec

tural firm acting as principal. Id. (See, paragraphs 4,5,

and 7 of complaint). Present practices of the governmental

defendants continue to show a double standard towards black

and white architectural firms and have the purpose and effect

of discriminating against black architectural firms, including6/

these plaintiffs, on racial grounds.

c/ The complaint alleges that the governmental defendants

have never awarded architectural fees to black architectectural

firms in excess of $57,000."since racial segregation in public

facilities first was declared unconstitutional m 1954.

(paragraph 7b of complaint). Id. at 19.

6/ For example, in paragraph 7 of the complaint, the

nlaintiffs allege that in the fall of 1983, the defendant Metropolitan Board of Education of Davidson County, Tennessee

awarded two multi-million dollars contract involving construction

of two new comprehensive high schools, one predominantly white

and the other predominantly black. Id. at 18.

Awards to the contract went to two white ^S^SSalified firms even though plaintiffs were equally, or better, qualified

to perform the work. Moreover, the complaint alleges that the

defendant school board specifically advised one of the white

firms that it was not necessary to have a joint venture with anv minority architectural firm, thus causing that^firm to

withdraw its offer to one of the plaintiffs for a joint venture. SS^graph 7c of the complaint alleges that the reasons given by

the board of education for not awarding any portion of the contract to plaintiffs were pretexts for racial discrimination.

Similarly, in 1981, the complaint alleges that defendant

Metropolitan Naihville Airport Authority refused to_award any

portion of contract for the construction of a ■ terminal

facility at the Nashville Airport to any of the plaintiffs.

AlthouhYplaintiffs were the only black architectural firms in

middle Tennessee and some of the PlaintJ ^ s Tennesseeexperience working on airports outside the State of Tennessee,

6

To combat the racial discrimination which they had

experienced, plaintiffs-appellants McKissack & McKissack &

Thompson, Harris Associates, and L. Quincy Jackson entered

into an agreement, on May 31, 1984 establishing as a joint

venture an unincorporated association designated as the

Coalition for Equitable Minority Participation in Architec

tural Contracts in Tennessee (COMPACT). The three black

architectural firm-members of COMPACT are the only minority

firms with a home base in middle Tennessee. Together, the

three firms, along with COMPACT, have approximately ten (10)

licensed architects. (Jt.Appendix H, at 66, 123, August 17,

1984).

The May 31, 1984 agreement establishing COMPACT states

that the three black firms composing COMPACT "have not

received their fair share of the professional contracts

awarded to architects by public and private agencies" and

that it is necessary for the three firms to come together in

creating COMPACT for the purpose of "immediately alleviating

jj/ (Continued)

the defendant Authority nevertheless awarded the work for

the project to a joint venture of two predominantly white

architectural firms. (Paragraph 7d c^ 1“ t) *d C°St for the project ultimately exceeded $50,000,000. Id.

7/ Williams-Russell & Johnson, the minority architectural

firm chosen by defendant-appellee Gresham & Smith to work

with it on the Nashville Airport, has its home base in Atlanta,

Georgia. (Jt. Appendix .II, at 42, 123, August 17, 1984).

7

and ultimately eliminating said racial discrimination and

opening the entire range of architectural awards, both

public and private, to said black architects and architec

tural firms."

Paragraph 3 of the May 31, 1984 agreement gives each

member firm an equal voice in the affairs of COMPACT and an

equal share of the profits of the joint venture. Paragraph

5 of the agreement, the provision which the court below held

violated Section a of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. §1, states

the following:

5. COMPACT shall delineate specifically

and in writing the areas of marketing for architectural contracts which it

wishes to pursue on a joint venture basis

for the benefit of its members and shall

also designate specifically the areas

which members are free to pursue in their

own private marketing activities apart

from COMPACT. No member shall pursue

or accept as an individual firm without

agreement of all members of COMPACT in writing in advance, any project which COMPACT has targeted or is pursuing in £/any way as a potential project for COMPACT.

The effect of the last sentence of Section 5 above is to

prohibit members of COMPACT who participate in its prepara

tions for targeting or pursuing bids on architectural

contracts, from taking thereafter individual, or separate,

8/ Similarly, Article V, Section (a) of COMPACT'S by

laws provide that "No member shall pursue or accept as

an individual firm without agreement of all members of COMPACT in writing in advance, any project which COMPACT

has targeted or is pursuing in any way as a potential

contract for COMPACT." Jt. Appendix I, at 8b.

8

action on their own behalf for the same contract.

COMPACT was established in order to pool the resources

of the three small minority architectural firms to provide

"various professional abilities and to have a greater number

of people available to do work" on projects bigger than any

10/of the three could do alone. (Jt. Appendix II, L. Quincy

Jackson at 130-131.

Since its formation, COMPACT has targeted two projects,

the Nashville airport terminal project, which is the subject

of the present interlocutory appeal, and a downtown Nashville

convention center (L. Quincy Jackson, Jt.Appendix II, 87, August 17,

1984). The May 31, 1984 agreement establishing COMPACT

9/

9/ Neither Section 5 of the May 31, 1984 agreement nor

Article V, Section (a) of the by-laws contains any provision

regulating members' conduct, or that of COMPACT, in situations

where a member firm pursues or targets a project first. The

affidavits, depositions, and testimony on the motion for summary judgment and for a preliminary injunction did not

cover this possibility.

10/ During the hearing on plaintiffs' request for a

preliminary injunction, plaintiff L. Quincy Jackson testified

that his "purpose for joining COMPACT was to be able to work

with minority architects on large projects . . . that were

beyond the capabilities of small architects to work on and

. . . because (each) of the three firms have had in the past

and in the present, difficulty in acquiring larger jobs and

particularly those jobs that are funded by local, state and

federal governments." ( Jt. App. 11,85-86) . Jackson also

testified that Clarke Sharpe, "civil rights commissioner of

the FAA had stated at a meeting that the Metropolitan Nashville

Airport Authority "had at that time not involved minority participation from 1981 through 1984." Jt. Appendix II at 91,

August 17, 1984.

9

that the formation of COMPACTstates, in the opening page,

is designed to eliminate racial discrimination in the "entire

range of architectural awards, both public and private."

This case arises out of a denial of job opportunities for

COMPACT to provide architectural services in connection with the

design and construction of a planned expansion of the Nashville

Airport. The airport is operated by the Metropolitan Nashville

Airport Authority (MNAA). Prior to the formation of COMPACT

on May 31, 1984, the MNAA had awarded in 1980 a contract to

perform the schematic design phase of the construction of a

new terminal complex at the Nashville airport to a joint

venture consisting of an out-of-state architectural firm

Reynolds, Smith and Hills, and a local firm. The local firm

chosen was defendant Gresham, Smith and Partners, then doing

business under the name of Gresham and Smith. In early

1982, the work on the schematic design phase was completed.

(See, Memorandum of Metropolitan Nashville Airport Authority

In Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for a Temporary Restrain

ing Order and/or Preliminary Injunction, p. 3-4).

In the fall of 1983, plaintiff L. Quincy Jackson

attended a conference concerning the construction phase of

the planned expansion of the Nashville airport and attempted

to secure information to enable his firm to obtain work on

the airport project (Jt. Appendix II 87-88). On May 18, 1984,

the Board of Commissioners of the MNAA decided to proceed

with the construction phase of the new airport terminal

10

Project and simultaneously decided to retain only one of

the two joint venture firms. On or after June 22, 1984,

the Board selected the local firm of Gresham, Smith and

Partners on the ground, in part, that a local firm was

needed to establish local accountability. (MNAA's

Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for a

Temporary Restraining Order and/or Preliminary Injunction,

pp. 4-5). The proposal of Gresham, Smith and Partner

provided that other professional firms would work with it

as a team. No provision for minority participation, however,

was included in the proposal. Id.

During this period, COMPACT was formed and its

representatives sought participation for COMPACT in the

contract award to Gresham, Smith and Partners as a part of the

team. The MNAA had a stated policy favoring minority partic

ipation. Id. (Also Jt. Appendix II at 27-43,87-99). COMPACT had

previously sought participation in the airport work prior to

the MNAA's decision in June, 1984 to select Gresham, Smith

and Partners but had not been allowed to bid on the project

as a local architectural firm despite a request to do so.

After June 1984, Gresham and Smith proceeded to obtain

design implementation subcontracts. Their general practice

had been to parcel out jobs to black firms sufficient to

obtain a token participation that would comply with

the civil rights law and allow them to get federal funds.

Black participation, however, would be limited to no more

than 10%. Within this limit of 10%, the City or the

11

principal contractor would set the three black firms into

competition among themselves, forcing the minority architects

bids downward to a lower than competitive price, thereby

exploiting the very individuals that the law is designed to

protect.

COMPACT approached Gresham and Smith and stated

that COMPACT, as a minority firm, was now "big enough

to handle major work in excess of the 10% limit. It

asked to participate as a joint venturer, or a member of the

team, with Gresham and Smith. Gresham and Smith declined

to bargain with COMPACT on this basis, and sought instead

to get federal funds by selecting an out-of-state minority

owned architectural firm in Atlanta to whom it could grant

11/

token participation.

Following the refusal of Gresham, Smith and Partners

to select COMPACT as part of its team or as a minority

business enterprise participant as required by MNAA's

policy, or to bargain seriously and in good faith with it,

ia/ COMPACT alleged that MNAA discriminated by denyingMick architectural participation in the design phase between

and 198fin violation o f Federal Civil Rights acts andregulations? ̂ b^employing a i-al white firm^ith^no^irport

architecturaiacontractbfor1design1implementation to the same

allowed * to W d f thereafter the white firm applied a non-

to^omplyHbelatedly^ith^he^ederally-mandated^ininorit^ ̂

participation in the second stage. Jt. Appendix

12

COMPACT and its members instituted the instant action under

federal civil rights statutes 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982, 1983,

1985, 1986, 1988, 2000d; the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. §1, and

the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States.

Defendants are governmental bodies and officials

responsible for racially discriminatory action in the award

of contracts for architectural services in the design and

construction of airport facilities and public schools in

Nashville and Davidson County, Tennessee, and private parties

acting as agents of said officials. The defendants are the

Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County,

the Metropolitan Nashville Airport Authority, the Metropolitan

Board of Education, the Metropolitan Airport, officials of

the aforementioned public bodies, the Mayor of Nashville,

Hart-Freeland-Roberts, Inc., Architects & Engineers, and

Gresham, Smith & Partners.

The complaint prayed for an injunction restrain

ing defendants from engaging in racial discrimination or

restraint of trade against plaintiffs, enjoining the MNAA

and the Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson

County to engage COMPACT for architectural services in

conjunction with the design and construction of the terminal

at the Nashville Airport, and for a judgment awarding damages

to plaintiffs for their injury.

13

At a hearing on August 17, 1984 on plaintiffs’

motion for a temporary restraining order and for a preliminary

injunction, the district judge opined that the May 31, 1984

agreement establishing COMPACT violated federal anti-trust

laws. Thereafter, defendants filed a motion to grant them

summary judgment. On the basis of the evidence presented

at the hearing on the motion for a preliminary injunction and

the depositions and pleadings, the district judge granted, on

October 18, 1984, partial summary judgment dismissing the

claims in the complaint in which the district judge held

that plaintiffs had conspired by doing business as COMPACT,

i.e., the claims involving the design and construction of

the Nashville airport.

In support of the partial summary judgment, the district

court made several findings of fact. First, it found that

plaintiffs tried to "exert monopolistic leverage on Gresham

and Smith to force it to accede to COMPACT’S demand for a ^

more substantial participation share of the design contract"

(Jt. Appendix I, at 33); that plaintiffs refused to negotiate

12/ The market for architectural work on the Nashville

"airport was not limited to firms in Tennessee. The initial

design work on the contract was performed by a venturebetween a Florida architectural firm, Reynolds, Smith and

Hill, and the Tennessee firm of Gresham and Smith. See

Jt. Appendix I, at 33, at ft. 3. Similarly, the marke . a minority business enterprise participant was also not

limited to Tennessee. Gresham, Smith and Partners awarded

a subcontract to a minority firm William, Russell and Johnson,

from Georgia. (See Jt. Appendix I, at 43, 49).

14

with defendants on the design contract except through

COMPACT^ (Jt. Appendix I, at 33); v and that plaintiffs

n / The testimony of plaintiff L. Quincy Jackson contra- 41' court's assumption that the three firms

comprising COMPACT refused to do business ^ h e r ^ h a n ^ ^

^ ^ tha^I^eSk* individually?511 still have that kind of

aid I still have that right." Jt. Appendrx II,

at 86.

t v, sign testified that the claim that he refusedJohnson also testn o -f compact wasto deal with defendants except a. an agen^|*.C0MPACT based upon a misunderstanding. He said that.

The request for Exhibit 13 was

not a personal request as by L. Quincy

Jackson as an individual. This ^for

mation, as all other information, was

requested to be sent to COMPACT - the

group, COMPACT - which w*s_the. gro£Pq_ith that met on the 10th with Gresham & Smith.

The information was sent to me to

be judged as an individual. I refused to

accept the package as L. Quincy Jackson.

Therefore, the package was returned

several times and I talked with the secretary about the package and the package

uas nicked up by a member of COMPACT ana

b i l l e d by members of COMPACT, and not by L. Quincy Jackson as an individual

architect. Jt. Appendix I ,

Later, at the hearing on the preliminary injunction,

Jackson testified that:

I refused to accept the material

as an individual because I did not request X e n i a l as an individual COMPACT

requested the material and I think it

should have been addressed to COMPAC

so that all three groups will have the same material and have the same opportunity to look at it. As it was so addressed,

it was only addressed to me. Jt. Appendix

II, at 108-109.

15

demanded 50% of the design contract (Id. at 34).

Second, the district court found that minority business

enterprise set-aside shares on public contracts^constitute

a discrete submarket for architectural services (Jt.

Appendix I, at 35-36), and that, in creating COMPACT,

14/

14/ Desnite the finding of the district court, the

evidence il in conflict on whether or not ^i^St L SSnJy a 50% share of the architectural design contract. • Q YJac£so?rtestimony on this issue illustrates the extent of

the conflict. The testimony is as follows.

Witness: I meant to make a correction there that someone mentioned in an earlier

testimony that we wanted a 50% - I

believe Mrs.McKissack -

Court: Mrs. McKissack left that impression.

Witness: She might have been a little disturbed.

The first time in a situation like this

and taking over the situation of tips

magnitude which she had to do and this

pressure. We did not discuss how we

would divide the work up.

What we really discussed that I

fe]_t that Gresham & Smith might have been afraid of, we insisted almost that

we have a joint venture because in a

joint venture, you can designate responsibilities easier than you can

with an association.

We never discussed how much money

we would get. It was sort of brought

out to us at the July 3rd meeting, that

it was 10% of whatever it was - dating back from '81 to '84. Jt. Appendix II,

at 118.

15/ The district court held as a matter of law that

S S I ^ ^ ^ t efrifc«?eS^ I r ^ 1 o r l r ? h i ? : c tural „

i i S raay c°mp

16

plaintiffs "did not attempt to increase their market power^

in the general architectural market for Middle Tennessee"-

(Jt. Appendix I, at 36).

Third, the district court held that COMPACT imposed

a "blanket prohibition on its individual members' right to

15/ (Continued)

" a l l

of subcontracts to the fullest exue r s 637(d)efficient performance of this contract. 15 O.S.C.S. Wl

(3) (B) .

COMPACT'S operations extend both to public and private COMPAtl s opeidu No evidence was takensss future

businessPCOMPAcrCcontemplates°private contracts will be.

M et. ^ J a l n t t l f JacksonagaventS r5 o iS w !S g ’t i s t f ^ on

this issue:

Mv purpose for joining COMPACT

was to be able to work with minority architects on larger projects and in

particular projects that were beyond

the capabilities of small architects

to work on and because . . . or tne

three firm have had in the past and in the present, difficulty in acquir

ing larger jobs and particularly, those

jobs that are funded by local, state and

federal governments.

Most of the jobs that even local

government permits small firms to do have

been joint ventures with majority firms.

17

compete for the airport contract . . . (which) preempted

competition between COMPACT and its members and, also,17/

between the individual COMPACT members themselves" (Jt.

Appendix I at 42), that net productive capacity of the

members of COMPACT was reduced, rather than increased, by

COMPACT'S operations (id at 42); and that COMPACT'S

demand for a share of the design contract together with

its members' refusal to negotiate except through COMPACT * I,

16/ (Continued)

. . . We felt . . . that by

coming together . . . that we will

be capable of rendering a service

throughout the community that is

compatible to a larger firm. Jt.

Appendix II, at 85-86.

17/ Neither the May 31, 1984 agreement establishing

COMPACT nor COMPACT'S by-laws prohibits members of COMPACT

from competing against each other. See Jt. Appendix I, at 61, 62,' 86-87. The by-laws of COMPACT states specifically

that "each individual member of COMPACT is free to pursue their own architectural and other professional activities

apart from COMPACT and just as if each such member had no

connection with COMPACT" with the exception of areas

delineated for joint ventures through COMPACT. Jt. Appendix

I, at 86-87.

Moreover, the only competition specifically prohibited

by the by-laws or the May 31, 1984 agreement is competition

on a particular target by any of the individual members against COMPACT after "COMPACT has targeted or is pursuing

in any way (a project) as a potential contract for COMPACT"

(the by-laws permit such competition, however, with the

agreement of all members). See Jt. Appendix I at 87. Plaintiff Jackson explained this provision in the following

way:

If I bring a job to COMPACT and

say we're going after this particular

job and if someone calls me the next

day and say Quincy, I want you to

participate in the job, I have an

18

"represents a genre of price fixing.

18/ (id at 47) .

17/ (Continued)

an obligation to COMPACT to say no, I

am with COMPACT and I cannot partici

pate or will not participate with any

one on a job separate. Jt. Appendix

II, at 87.

Jackson also pointed out that:

The difference is that if I come to

COMPACT as one of its members with

a large project that I feel that I have

some insights on, secured with myself

or with someone else, that we can all

secure and target after that particular

project as one unit, yet still be an independent practicing firm. Jt. Appendix

II, at 86-87.

Jackson's testimony implies that the provisions

the May 31, 1984 agreement and by-laws which prohibit competition against COMPACT by individual members after

COMPACT has taken necessary steps to pursue or target a

oroiect serve to secure COMPACT against the possibility

S a t a m e ^ S might use its insider status in order to

appropriate inside information which COMPACT used m i s

computations and deliberations to target the contract.

5he district judge, in finding against COMPACT on this

issue did1not^ however, seek to ascertain the extent to which the alleged noncompetitive provisions were used to prevent unauthorized appropriation of inside information

tendered by the other partners to the joint venture COMPACT.

18/ The district judge seems to have assumed as a matter

of law that COMPACT'S prohibition of a member firm from

competiting with it on projects targeted by COMPACT, was

equivalent to price-fixing. The testimony, however, on the preliminary injunction went the other way. Jackson

testified that, in the negotiations for the airport design

"We didn't state any figure. We stated no dollar figur ;

we stated no percentage." Jt. Appendix II, at 163.

Jackson also stated that:

my expression in the formulation of

COMPACT . . . was the fact that not only

had my firm been discriminated against on

a number of occasions, but the Harris

19

The district judge granted summary judgment dismissing

the claims involving the airport on the ground that the

agreement among COMPACT members prohibiting the members, in the

absence of consent, from pursuing contracts targeted, or

pursued, by COMPACT constituted a contract, combination or

conspiracy in restraint of trade in violation of section 1

of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. §1. The court held that

plaintiffs' actions in forming COMPACT was a per se violation

of section 1 of the Sherman Act notwithstanding plaintiffs'

contention that the COMPACT agreement was a joint venture

subject to the rule of reason test.

The district court also held that the purpose for

which COMPACT was formed was irrelevant in determining the

legality of plaintiffs' actions under the anti-trust laws and

the applicability of the per se rule. Holding that plainitffs'

activities constituted an illegal horizontal division of a

submarket and an interference with the free market price

structure, the district court concluded that granting * I

18/ (Continued)

which was a small firm also had had

the same problems. And I could see that the McKissack firm had also received

over the years — therefore, we felt — and ^

I think we all joined together in this

feeling - that the idea of getting out here trying to earn a dollar per se was

not our total objective. . . . that we

are definitely trying to break down the

barrier - you can call these barriers or whatever kind of discrimination you want

to call them. Jt.Appendix II, at 147.

20

plaintiffs' request for relief would further the objectives

of an unlawful anti-trust conspiracy and that accordingly

summary judgment dismissing the claims involving the

conspiracy was proper and required.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The central issue in this case is whether plaintiffs'

right to seek judicial enforcement of the nation's civil

right against public agencies practicing racial discrimi

nation can be thwarted by an erroneous application and

interpretation of federal antitrust laws. This is an

issue of federal law and policy arising under specific

federal statutes prohibiting racial discrimination by public

and private agencies, 42 U.S.C. §§1981-2000d, and under

provisions of the Small Business Act, 15 U.S.C. §637(d)

i K i v i t f e s S S S S =o£ f e - r -

Presidents Conference v. Noerr Motor Freight, In£., 365 U.S.n , MQCi'n --united States v. Pennington, 381 U.S. 657 .

Plaintiffs'claim that the "Airport Authority should be the ones to select the minority” participant (Jt. Appendix II,

u. 33) and not the private firm of Gresham, Smith an ?Ltn!rs anS that tc the extent that their insrstence upon

M S - ^ i S i n n i ' a°r ^

^HrStictif^SofSTthifihe'soSpS o^lhe Noer-Pennington

doctrine.

21

»

affirmatively requiring public agencies receiving federal

funds to accord "small business concerns owned and controlled

by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals . . .

the maximum practicable opportunity to participate m the

performance of contracts let by any Federal agency."

The purpose of the antitrust provisions of the

Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. §1, is to help the underdog and the

powerless against great aggregations of economic, social,

and political power, and not to provide a sanctuary for

violators of federal laws prohibiting racial discrimination.

See remarks of Senator Sherman in support of the Sherman

Act, 21 Cong. Rec. 2460 (1890) .

in enacting the antitrust law, Congress intended to

increase diversity, promote pluralism, see remarks of

Representative Ceiier, 95 Cong. Rec. 11486 (1949), and

remarks of Senator Kefauver, 96 Cong. Rec. 16452 (1950),

urging amendment of the merger law, and to give the little

man and small businesses a clear field and a fairer opportunity

to try. See remarks of President Wilson stating that the

passage of the Clayton Act:

(w)ill bring new men, new energies, and

a new spirit of initiative, new blood, into the management of our great business

enterprises. It will open the field of

industrial development and origination

to scores of men who have been obliged

to serve when their abilities entitle

om -t-o direct

Address by President Wilson on Trusts and Monopolies

before Joint Session of Congress (Jan. 20, 1914), H.R.

Doc. No. 625 63rd Cong., 2d Sess. 5(1914).

22

The United States Department of Justice, the Federal

Trade Commission, and the Federal courts recognize the need

to place limits on the use of the antitrust laws. The

Justice Department follows the rule that antitrust laws must

be used only against challenged transactions that are

"inefficient." "Interview with William F. Baxter, Assistant

Attorney General in Charge of the Antitrust Division, Report

from Official Washington," 51 A.B.A. Antitrust L.J. 23 (1982);

"Panel Discussion — Interview with William F. Baxter," 50

A.B.A. Antitrust L.J. 151 (1981).

Both the FTC and the Justice Department apply restric

tions on the use of antitrust laws to joint ventures. The

FTC approved the joint venture between General Motors, the

number one auto maker in the world and Toyota, the number

one auto maker in Japan, to produce a new compact car.

General Motors Corp./Toyota Corp., 48 Fed. Reg. 57246, 57314

(1983), 49 Fed. Reg. 18289 (1984), 3 CCH Trade Reg. Rep.

5 22,139 (1984). The Justice Department approved a joint

venture of all of the U.S. automobile companies to develop

and pool their developments of automobile pollution devxces.

United States v. Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Ass’n, 1982-83

Trade Cas. f 65,175 (1982) (liberalizing prior consent judg

ment) .

Similarly, the merger of LTV Corporation and Republic

Steel Corporation, the second and sixth largest steel companies

in the United States, was approved by the Justice Department.

23

The FTC approved a 13 billion dollars acquisition by Standard

Oil Company of Gulf Oil Company, one of the other "seven

sisters." United States v. LTV Corp., 1984-2 Trade Cas.

i 66,133 (D.D.C. 1984)(consent order requiring minor

divestiture). Standard Oil, 3 CCH Trade Cas. 1 22,144 (1984).

In the federal courts, limits have been placed on

the application of antitrust laws through the use of economic,

non-interventionist theories that support a minimalist approach

to antitrust. See Brunswick Corp. v. Riegel Textile Corg.,

1985-1 Trade Cas. 1 66,333 (7th Cir. 1984); United States v.

Waste Management, Inc♦, 743 F.2d 976 (2d Cir. 1984). See

generally Easterbrook, "The Limits of Antitrust," 63 Texas L.

Rev. 1 (1984).

In view of this history of the antitrust law, plaintiffs

submit that the District Court plainly erred in interpreting

Section 1 of the Sherman Act to find an antitrust violation

and in dismissing COMPACT'S claims. First, the court erred

in holding that the alleged antitrust violation was a

defense to civil rights claims. Second, the court erred in

adjudicating the alleged antitrust violation before deciding

the merits of the civil rights claim. Inasmuch as federal

civil rights law requires defendants to cease racial dis

crimination in the award of public contracts and to accord

COMPACT consideration for meaningful participation in

federally funded contracts, a federal antitrust violation

cannot be predicated upon acts taken by victims of racial

24

discrimination to secure

objectives.

compliance with civil rights

Third, the district court erred in holding that the

May 31, 1984 agreement creating COMPACT organization was a

per se violation of the antitrust laws rather than subjecting

it to a rule of reason inquiry or dismissing the antitrust

defense on the ground that COMPACT had neither the purpose

nor the power to harm competition either in the general

market for architectural services or in the market for

services by minority architectural firms.

Fourth, the district court erred in using summary

judgment to decide the claims and defenses below when there

was disputed questions of fact. These errors by the district

court require the Court to reverse the judgment below and

remand the case for trial on plaintiffs' civil rights claim.

ARGUMENT

I.

APPELLEES' ANTITRUST DEFENSE IS NOT

A DEFENSE TO APPELLANTS' CIVIL RIGHTS _________ CLAIMS________________

The District Court granted partial summary judgment on

the ground that plaintiff has violated Section 1 of the Sherman

ACt, 15 U.S.C. § 1, in creating a joint venture, COMPACT, to

combat racial discrimination in the award of public and

private contracts for architectural services, and that plaintiffs'

request for relief in their civil rights claim could not be

granted without implicating the district court in the execution

25

of an agreement illegal under Section 1 of the Sherman Act.

In deciding against the enforcement of appellants'

claims as plaintiffs herein, the district oourt purported to

invoke a legal principle prohibiting courts from granting

relief on non-antitrust claims if to do so will enforce the

conduct made illegal by the antitrust laws.

The principal case relied upon by the district court

to support this decision was Continental Wall Paper Co. v.

Louis Voight & Sons, 212 U.S. 227 (1909). The plaintiff

corporation there sued to recover for payments due on the sale

of wallpaper to defendant. Plaintiff however was the sales

agent for wallpaper companies doing business as a pool and

selling at excessive prices fixed pursuant to the pool agreement.

The Supreme Court denied enforcement of the contract on the

ground that giving relief for the excessive price fixed by

plaintiff could make the court a party to carrying out a

restraint prohibited by the Sherman Act.

The holding in Continental Wall Paper Co., v. Louis

Voight & Sons Co., supra, was expressly qualified in D.R.

Wilder Mfg. Co. v. Corn Products Ref. Co., 236 U.S. 165 (1915).

In this case, plaintiff, the Corn Products Ref. Co., sued

defendant to recover the price of glucose, or corn syrup, sold

to it. Defendant, the D.R. Wilder Mfg Co., asserted a defense

of nonliability on the ground that plaintiff was a combination

of all manufacturers of glucose, or corn syrup, in the United

States, illegally organized with the object of monopolizing all

26

dealings in corn syrup or glucose in violation of the anti

trust laws. Defendant further alleged that the prices

charged by the monopoly were excessive, and that the totality

of these facts brought the case within the rule established

in Continental Wall Paper Co. v. Louis Voight & Sons Co.,

supra.

The Supreme Court rejected this contention. It said

that Continental Wall Paper Co., supra, was misunderstood and

clearly inapposite. The Court stated that the assertion

that the plaintiff refining company had no legal existence

because it was an unlawful combination in violation of the

anti-trust laws was irrelevant to the issue of liability for

payment of the purchase price since such a defense was a

"mere collateral attack on the organization of the corporation.'

Id. 236 U.S. at 172. The Court went on to proclaim that

"this is but a form of stating the elementary proposition that

courts may not refuse to enforce an otherwise legal contract

because of some indirect benefit to a wrongdoer which would

be afforded from doing so, or some remote aid to the accomplish'

ment of a wrong which might possibly result." Id. (citing

Connolly v. Union of Sewer Pipe Co., 184 U.S. 540 (1902)).

In response to the argument that the decision in

Continental Wall Paper Co., supra, required a contrary result,

The Court said "In the first place, the contention cannot be

sustained consistently with reason. It overthrows the general

law/" Id. 184 U.S. at 173. In the second place, the Court

27

said there was "no support afforded to the proposition that

the anti-trust act authorizes the direct or indirect suggestion

of the illegal existence of a corporation as a means of

defense to a suit brought by such corporation on an otherwise21/

inherently legal and enforceable contract." Id. at 176.

Other decisions of the Supreme Court have reached a

similar result. See, Bruce's Juices, Inc., v. American Can

Co., 330 U.S. 743 (1947); A.B. Small Co. v. Lamborn & Co.,

267 U.S. 248 (1925). One of the leading cases is Kelly v.

Kosuga, 358 U.S. 516 (1959). The respondent in Kell*,

supra, sued petitioner for failure to complete payment for

the purchase price of onions as required by an agreement.

Petitioner defended on the ground that the sale was made

pursuant to and part of an agreement which violated the

Sherman Act. The district court granted a motion striking

the defense. Both the court of appeals and the Supreme

Court affirmed.

The Supreme Court's majority opinion stated that "As a

defense to an action based on contract, the plea of illegality

based on violation of the Sherman Act has not met with much

favor in this Court." Kelly v. Kosuga, 358 U.S. at 518.

Citing D.R. Wilder Mfa. Co. v. Corn Products Ref. Co., supra,

21/ The case of Connolly v. Union Sewer Pipe Co., infra,

overruled on other grounds in Tigner v. Texas, 310 U.S. 141

(1940) was also one in which the Supreme Court held that the

formation of a combination in restraint of trade in violation

of the Sherman Act did not preclude a company from suing

upon collateral contracts.

28

the Court stated that it had decided there that "the Sherman

Act's express remedies could not be added to judicially by

including the avoidance of private contracts as a sanction."

Id. 358 U.S. at 519.

The Court emphasized that federal courts should avoid

"(s)upplying a sanction for the violation of the Act, not m

terms provided and capricious in its operation." 358 U.S.

at 521. Quoting, in part Justice Holmer's dissenting

opinion in Continental Wall Paper Co., v. Louis Voight_&

Sons Co., supra, where the enforceability of a contract was

at issue, the Court said "Past the point where the judgment

of the Court would itself be enforcing the precise conduct

made unlawful by the Act, the courts are to be guided by the

overriding general policy "of preventing people from getting

other people's property for nothing when they purport to be

buying it." Id. 358 U.S. at 520-21. Compare Perma Life

Mufflers v. international Parts Corp., 392 U.S. 134 (1968).

See also Chrysler Corp. General Motors Corp., 1985-1

Trade Cas. 5 66,391 (D.D.C. 1985)(plaintiff's alleged anti

trust violation is no defense).

Here, the applicable federal policy is set by two

distinct sets of federal civil rights law. One set,

embodied in 42 U.S.C. §1981-2000(d) forbids racial discrimi

nation. The other set, 15 U.S.C. §637(d), requires the

"maximum practicable opportunity to participate m the

performance of contracts let by any Federal agency.

29

The complaint alleges that defendants violated both sets of

civil rights law. No contention is made, either by the

court below or by the defendants, that they denied plaintiffs

participation in the airport contract on the basis of the

alleged violation of the antitrust laws or even that they,

defendants, were aware of the alleged violation prior to

commencement of this action.

The district court refused to entertain plaintiffs'

civil rights claims solely because of one provision, among

many, of the May 31, 1984 agreement establishing COMPACT.

That provision, prohibiting individual members firms from

pursuing projects which are being jointly targeted or pursued

by them through COMPACT, was not found by the district court

to be the essence of the May 31, 1984 agreement.

Moreover, the provision was clearly separable from

other protions of the Agreement. In fact, plaintiffs

counsel, at the argument on the motion for summary judgment

on September 7, 1984, specifically stated, on page 43 of

the transcript of the argument, that "in terms of fashioning

relief, the Court should simply strike out paragraph 5 of

the COMPACT agreement which has not been invoked in any 2 2

fashion as a factual matter and allow the case to proceed.

Jt. Appendix II at 327.

22/ See footnote 13 infra.

In short, the district court below could have granted

the relief requested by COMPACT without "enforcing conduct

made unlawful by the (Sherman) Act." Clearly, the anti

competitive provision was separable from the remainder of the

agreement. It was neither essential to the agreement nor the

basis for defendants' refusal to award an architectural

contract to COMPACT. Moreover, there is no evidence showing

in fact that any of the member firms of COMPACT refused to

bid on the airport project because of the anticompetitive

provision in the May 31, 1984 agreement and the by-laws.

Plaintiff Jackson testified that his firm did not respond

to the invitation to the bid because it had been mailed, in

error, to him as an individual rather than to the party,

COMPACT, which had requested it.

The anticompetition provision was clearly collateral

to plaintiffs' claiirs for relief and thus falls squarely

within the principle of Kelly v. Kosuga, sugra. The anti

trust defense should therefore be stricken.

Moreover, striking the defense will not prejudice the

right of defendants to bring a separate suit, or to counter

claim, for any injury which the alleged anticompetitive pro

vision might cause to them. If defendants are shown to have

23/ See footnote 13 infra. Moreover, it is unclear to

what extent a subsequent bid by his firm on the airport proj ect would have been based on confidential information on costs prices, and personnel disclosed by the other two

member firms in their preparation of COMPACT s bid. See

footnote 17 infra.

31

violated plaintiffs* civil rights, then plaintiffs are

entitled to a declaratory judgment declaring their rights

and an injunction against defendants' continued wrong-

24/doing. Defendants' attempt to preserve their freedom

to discriminate by condemning plaintiffs' small, minority-

business consortium as monopolists trivializes the anti

trust laws and makes a mockery of civil rights. Accord

ingly, the judgment below should be reversed.

II.

CIVIL RIGHTS STATUTES PREEMPT INCON

SISTENT ANTITRUST LAWS AND REQUIRE THE ANTITRUST LAWS TO BE INTERPRETED

AND APPLIED TO CARRY OUT THE SPIRIT

AND THE PURPOSES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS

LAWS___________ ____

The District Court erred in deciding the antitrust

defense before deciding the civil rights claim, for if

plaintiffs are entitled to prevail on their civil rights

claims then the civil rights laws preempt any inconsistent

antitrust law. If plaintiffs should not prevail on the

civil rights claim, then any antitrust violation is moot.

Therefore, the civil rights issues should be addressed first.

24/ We show in this memorandum that COMPACT is plainly

procompetitive and that such combined efforts to bring new

talent into a market are encouraged by the antitrust laws.

But even if, after trial, the Court could find that the

COMPACT agreement in some way offends the law, the court can

still fashion relief so as not to further the offense.

25/ The alleged "violation" has had no impact and has

"caused no injury. In a private antitrust suit there is no

32

Congress may passThe law of preemption is clear,

legislation inconsistent with a prior statute, such as the

antitrust laws. When the mandate of the subsequent legisla

tion cannot be carried out except by displacing principles of

antitrust, then the antitrust laws are repealed to the extent

necessary to make the subsequent legislative scheme work.

United States v. National Association of Security Dealers,

422 U.S. 694 (1975); Gordon v. New York Stock Exchange, 422

U.S. 659 (1975); Pan American World Airways v. United States

371 U.S. 296 (1963).

Here, Congress has enacted statutes, both before and

after the passage of the Sherman Act, 42 U.S.C. §1981-2000d

which prohibit racial discrimination by public or private

persons, and which require that the "maximum practicable

opportunity to participate" in federally financed contracts

be afforded to small minority business enterprises such as

those of plaintiffs. In the instant action, three small

minority firms in middle Tennessee have combined to exercise

25/ (Continued)

violation without impact^

has not been m ] Private plaintiff has no standing toened with injury, the p ya1Sanovitz v. G. Heileman Brewing chaHenge the violati • ^ Dei. 19bTT See Brunswick

Co., 185-1 Trade cas. ^ / 477 (1977). Here,

S rePri n^h^atened injuryare not the victims of a vrolatron and

have no right to assert a violation.

33

their rights to be free of racial discrimination and to gain

a fair chance to participate in the market for architectural

services; their attempt to do so has been wholly unsuccess

ful in the marketplace, for, as events show, even joining

together they lack the capacity, or power, to get a meaning

ful foothold in the market; and then these small minority

firms are denied a day in court to prove their civil rights

claim on the ground that their coming together, without

regard to their purposes in doing so, violates the antitrust

laws.

26/

26/ During the hearing on the preliminary injunction, the

following exchange occurred:

Defendants' Counsel: Would it be correct to say. . . that all of these projects

are projects on which your firm

has either been the lead architect

or principally involved in the'

project?

Witness (Leatrice : Yes.McKissack)

Defendants' Counsel: . . . Boyd Park Community Center;Cameron School; Dudley Park

Community Center; Easely Memorial

Center; Goodlettsvilie Elementary

School; Hadley Park Bandstand;

Hayes Elementary School; Kings

Lane Elementary School; Lane Garden

Housing; Meigs School; North

Nashville Community Center & Branch

Library; Pearl Senior High School;

South Street Community Center; -

Tennessee Project 517 and 519 and

Washington Junior High School.

Aren't all those public projects

that were funded by tax money here

in Nashville? Excuse me, and Ford

Greene Elementary.

Witness: Mr. Leeman, that proves the point

that I was making.

34

By these statutes, Congress clearly meant to encourage

and promote whatever action or combination was necessary for

minorities to obtain meaningful opportunities to participate

in the market for architectural services. Minority firms

axe entitled to take those steps necessary to achieve the

statutory goals. Here, the three minority firms took steps

in this direction by forming COMPACT (although thus far with

out success).

Moreover, the undisputed evidence shows that a principal

purpose for forming COMPACT was to combat racial discrimination

by enabling the minority architectural firms to work on projects

that "were beyond the capabilities of small architects."

Jt. Appendix II at 85. Even COMPACT resources were limited,

however, since the three firms employed only twelve or thirteen

architects or draftsmen. Jt. Appendix II, at 66. Only seven

of the architects would have been immediately available for

work on the Nashville airport project. Id.

In view of COMPACT'S inability to obtain participation

in the airport contract, the formation of COMPACT as a joint

26/ (Continued)

• • •

Witness: . . . All these projects were basically

done before 1954 and they dealt with

housing blacks. Since 1954, if any --

if there are any projects on here that we acquired, it was a joint venture with

a white firm. Jt. Appendix II at 61-63.

35

venture was clearly necessary to protect the civil rights

of COMPACT and its members and thereby to enforce the civil

rights laws. Thus, if plaintiffs are correct in their

contentions concerning the civil rights claims, them any

inconsistent interpretation or application of the anti

trust laws would be preempted.

III.

THE COURT SHOULD STRIKE THE ANTITRUST

DEFENSE ON THE GROUND THAT COMPACT IS

A PROCOMPETITIVE JOINT VENTURE AND

THAT THE DEFENSE IS WITHOUT MERIT.

Plaintiffs are small minority businessmen trying to

get a foothold in the established and often exclusionary

market of architectural services. The market for archi

tectural services itself is notoriously non-competitive,

with prices higher than necessary. Jt. Appendix II, at 128.

The established majority firms in Tennessee are able to main

tain this noncompetitive equilibrium by erecting barriers to

the entry of minority firms and others who are not members

2J/of the "club." See Jt. Appendix II at 85-86. They do

this by systematically steering the important jobs away from

minorities. Id. at 91. By obstructing the flow of suffi

cient business, established firms assure that minority firms

27/ See, for an analogue in the legal profession, First,

""Competition in the Legal Education Industry," 53 N.Y.U.L.

Rev. 311 (1978) and 54 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 1049 (1979).

36

are too small to win the principal contractor positions. Id.

at 85-86.

Yet small business, such as the plaintiff firms and

their joint venture, COMPACT, are the hope for the future of

competition. They promise to bring new and vital

competitive pressures into the architectural services market.

Congressional policy recognizes this role for small business.

One expression of this policy is found in the Small Business

Act. 15 U.S.C. §631 et seq.

It is plain that, if COMPACT succeeds in getting a

meaningful participation in the airport expansion project and

thereafter in other projects, it will increase competition by

adding a new competitor, and it is plain that a legal environ

ment hospitable to COMPACT and similar ventures will increase

incentives for minority firms and thereby pave the way to their

greater participation and to more dynamic price competition in

the future. See United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp.,

110 F. Supp. 295, 347 (D. Mass. 1953), aff'd per curiam, 347

U.S. 521 (1954). The claim that this joint venture will

lessen competition is meritless on its face and should summarily

fail.

It is so clear that COMPACT is procompetitive if it

should get the chance to function in the marketplace that it

is difficult to understand how the District Court could have

labeled it a clear violation of law. The Court reached its

conclusion by misconstruing the facts, failing to draw all

37

%

factual inferences in favor of the non-moving party, and mis

applying the law, in numerous respects:

For example, the Court viewed COMPACT as if.it were a

cartel; namely, a combination of competitors to avoid bidding

against one another and thus to fix a common price. A cartel

is illegal per se.

The fact is that COMPACT is not a cartel. The members

of COMPACT come together in order to gain the ability to enter

a segment of the market for architectural services from which

they have been constantly rebuffed on grounds of small size.

This is the segment for architectural services as principal

contractor. They did not come together to eliminate their

bidding against one another on token jobs traditionally

offered by local governments and principal majority contractors.

Jt. Appendix II at 85-86, 118. The evidence offered by

plaintiffs supports this conclusion.

Thus, defendants have erected a Catch—22. None of the

three minority firms can get a significant participation alone

because each is said to be too small to do the job alone. And

all of the three minority firms cannot get a significant

participation together because they are said to be antitrust

violators if they bid together.

*

Fortunately the law is neither so rigid nor so unjust.

If combination is important to enable small competitors to bid

on a larger job than they could otherwise get, then combination

is legal under the antitrust laws. National Collegiate

38

Athletic Ass1n v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma,

104 S. Ct. 2948 (1984); Broadcast Music, Inc, v. CBS, Inc.,

441 U.S. 1 (1979). See Department of Justice Guide on Anti

trust and International Operations CCH Trade Reg. Rep. No. 266

(Feb. 1, 1977) , pp. 3-4 and Case C (Joint Bidding), (reprinted

in 1 Fox & Fox, Corporate Acquisitions and Mergers, App. 15).

The Court below misread the May 31, 1984 agreement.

It believed that the contract allocated territories. The

Court construed the clause prohibiting COMPACT members from

bidding on projects in "areas" targeted by the joint ventures,

by reading the word "areas" as referring to geographic terri

tories. In fact, it refers to projects targeted by the joint

venture. The covenants of the joint ventures were merely

boilerplate covenants pursuant to which partners agree not to

undermine the business of their partnership. Such covenants

have been valid since the days of the old common law. See

United States v. Addyston Pipe & Steel Co., 85 F.271 (6th Cir.

1898), aff'd, 175 U.S. 211 (1899); Brunswick Corp., [1979-1983

CCH Transfer Binder] f 21,623 at 21,786 (FTC 1979), aff__d in

relevant part sub nom. Yamaha Motor Co., v. FTC, 657 F.2d

979 (8th Cir. 1981), cert, denied sub nom. Brunswick Corp.

v. FTC, 456 U.S. 915 (1982). Similar covenants have

been incorporated in the form partnership contract sponsored

by the American Association of Architects. Jt. Appendix I,

at 65, Art. 2, Sec. 2.3.

The Court erred in assuming that a legitimate joint

39

venture must involve integration of facilities. Finding

no integration, it viewed the joint venture as se illegal.

While the Court made additional errors in this part of its

analysis, its principal error was a general misunderstanding

of the state of the antitrust laws. Antitrust was viewed

from a point in time when it was rigid, prohibitions were

overbroad, and technicalities stood in the way of activities

that were on balance procompetitive. See, Continental T̂ V.,

„ ctf Svivania Inc., 433 U.S. 36 (1977), overruling

n . , ^ gtat.es v. Schwinn 4 Co., 388 U.S. 365 (1967).

The Supreme Court has now revised this older, more

rigid approach by narrowing the use of the £er se rule to

restraints that unambiguously harm competition by decreasing

output. Thus, in Broadcast Music, Inc, v- CBS, Inc., 441

U.S. 1 (1979) where an activity involving some price-fixing

was held not to be per se unlawful, the Supreme Court said:

" ^ Y n ^ u ^ T o c ^ r ! “nd“ h ^ h ! V r a ^ c e

lacially Appears to be one that would always or almost always tend to restrict competition and

decrease output. . . . .

Id. at 19-20 (emphasis added).

In the recent case of National Collegiate Athletic * 1

28/

28/ It article.

Rev. 1523

ventures,

efforts o

to raise Analysis

made this error by referring p r o f e s s o r Brodley

"Joint Ventures and Antitrust Policy, 95 Harv.L.

(1982)f which dealt only with integrativejoint

In fact a joint venture is any combination of

,f o? mirS firms other than a cartel J^ement

price and to lower output). See Areeda, Antitrus_

1 360, p. 471 (3rd ed. 1981).

- 40 -

association v- Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma,

82 L.Ed. 2d 70, 104 S. Ct. 2948 (1984), the Court went farther

and held that consortia that on their face limit output

are outside the scope of the per se rule, and are reasonable

and lawful if the restraint is necessary to make the product

available or will otherwise increase output and thus be pro-

competitive. Id. at 82 L.Ed. 2d 83-84, 91-92.

The principle of reasonableness as developed in the

last eight years in cases such as Sylvania, BMI and NCAA

provides the lens through which the COMPACT joint venture must

be viewed.~/ This principle in turn yields the following rules

or guidelines.

First, joint selling agencies and joint bidding consortia

are entirely lawful if they are not on balance anticompetitive,

see, Rmadcast Mus i a ■ Inc, v. CBS Inc., su£ra; Appalachian

v- united States, 288 U.S. 344 (1933); United States

V. Columbia Pictures Corp., 189 F. Supp. 153 (S.D.N.Y. 1960);

Department of Justice Guide, su£ra. Second, if the purpose

of the joint venture is to enter a new market, increase

productive capacity, and to produce more rather than less, it

is in essence, presumptively valid. Id.

Even joint bidding consortia among dominant competitors

may be justified upon a showing that the individual members

?Q/ While the Court below cited BMI and NCAA it did not

Ully appreciate the significance of the cases to modern

antitrust analysis.

41

cannot alone handle so large a project. See Department of

Justice Guide, supra, and Department of Justice Press Release,

May 10, 1976, approving the consortium of General Electric

Company, Allis Chalmers Corporation and Westinghouse Electric

Corporation to bid jointly to provide turbine generators for

a major project in Latin America (cited in Guide, supra, at

p. 21, n.39. Joint bidding consortia may be justified when

the agency or body letting the contract determines, or

perceives, that the individual firms cannot handle the project

30/ . . .alone. Compare National Collegiate Athletic Association_v.

Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, supra.

Where the joint venture is shown to be lawful, either

because it lacks market power or facilitates a new or different

kind of market participation (both conditions are plainly met

in this case), then the next step of the inquiry is to examine

the covenants in the joint venture agreement to determine if

they unduly restrain trade.

The covenants that restrict the action of joint venturers

are tested under a rule of reason. They are lawful if reason

ably necessary to promote the business of the joint venture. Id