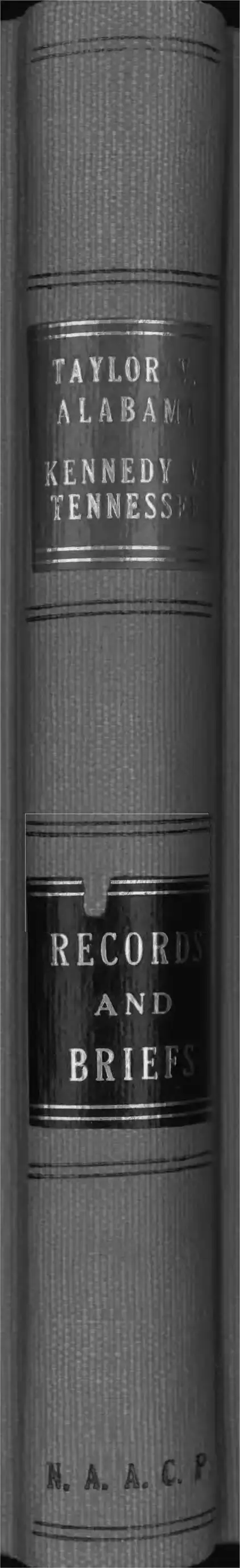

Taylor v. Alabama Record and Briefs

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1947 - January 1, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Taylor v. Alabama Record and Briefs, 1947. 4ddc637e-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9bb37ada-6bde-4ccf-b30b-add003a5a19c/taylor-v-alabama-record-and-briefs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

T AYL OR

A L A B A M

Ke n n e d y

T E NI E S' L -

R E C O R

A N E i

b r i e ;

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1948

No. 121 Miscellaneous

SAMUEL TAYLOR,

vs.

Petitioner,

TENNYSON DENNIS, Warden Alabama State

Penitentiary, Kilby, Alabama,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND FURTHER RELIEF

N esbitt E lm o re ,

Montgomery, Alabama,

T hurgood M ar sh a ll ,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

F r a n k D. R eeves,

F ra n k lin - H. W il l ia m s ,

C onstance B ak er M o tley ,

R obert L. Carter ,

Of Counsel.

TABLE OF CASES

PAGE

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. 8. 143 _______________ 4

Brisko v. Commonwealth Bank of Kentucky, 33 U. S.

(8 Pet.) 118 ____________________________________ 6

Brown v. Mississippi, 313 U. S. 547 _________________ 4

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227 ___________ _____ 4

Ex parte Hawk, 321 U. 8. 114 _____________________ 5,

Ex parte Quinn, 317 U. S. 1 .... ___________________

Ex parte Taylor, 249 Ala. 670, 32 So. (2d) 659 ________

Haley v. Ohio, 332 U. S. 596 ______________________

Hirota v. General MacArthur, 93 L. ed. (Adv. Op.)

119_____________________________________________

Holiday v. Johnston, 313 U. S. 342 _________________ _ 5,

Home Ins. Co. of N. Y. v. New York, 119 U. S. 129, 148;

122 U. 8. 636; 134 U. S. 594 ____________________

House v Mayo, 324 U. S 42 _______________________ 4, 5,

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458 ___________________

Lee v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 722 ____________________

Lisenba v. California, 314 IT. S. 219 ________________

Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401__________________

Marzani v. United States, — U. S. 93 L. ed .__________

Marino v. Ragen, 332 U. 8. 561_____________________

Mooney v. Hololian, 294 U. 8. 103____________________

New York v. Millan, 33 U. S. (8 Pet.) 120_____________ 6

Polack v. Farmers Loan and Trust Co., 157 U. S. 429,

586; 158 U. S. 601_______________________________ 6

Price v. Johnston, — U. S. —, 93 L. ed. (Adv. Op.)

993_____________________________________ ..._______ 5

Smith v. O’Grady, 312 U. S. 329 ____________________ 8

Taylor v. Alabama, — U. S. —, 92 L. ed. (Adv. Op.)

1394 2 8

Taylor v. State, 249 Ala. 130, 30 So. (2d) 256__________ 1

cn

^

co

oo

o

i

co

^a

to

m

oo

u

PAGE

U. 8. v. Adams, 320 U. S. 220 ________________________ 5

Vernon v. Alabama, 313 U. S. 547 __________________ 4

Von Moltke v. Gillies, 332 U. S. 708__________________ 5

Wade v. Mayo, 332 U. S. 672 _______________________ 4

Waley v. Johnston, 316 U. S. 101____________________

Walker v. Johnston, 312 U. S. 275 __________________ 5,

Ward v. Texas, 316 IT. S. 547 ________________________

White v. Ragen, 324 U. 8. 760 _____...________________

White v. Texas, 310 U. S. 530 _______________________4, 5,

Williams v. Kaiser, 323 U. 8. 471___________________

Statutes and Other Authorities

Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2241-2255 ______ 5

A Memorandum Decision, 40 Harv. L. Rev. 485, Janu

ary, 1927------1-------------------------------------------------- _____ 10

O

l

CC

^

^

Q

O

O

l

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1948

No. 121 Miscellaneous

S a m u e l T aylob ,

vs.

Petitioner,

T en n yso n D e n n is , Warden Alabama State Penitentiary,

Kilby, Alabama,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND FURTHER RELIEF

To the Honorable Chief Justice of the United States and

the Justices of the Supreme Court of the United

States:

Petitioner respectfully presents this petition pursuant

to Rule 33 of the Rules of this Court for a rehearing of

the above-entitled cause decided on the 7th day of Febru

ary, 1949, by an evenly divided Court of eight (8) Justices.

Petitioner respectfully submits the following reason why

the relief prayed for should be granted:

On November 19,1946, petitioner was sentenced to death

by electrocution upon a conviction of rape in the Circuit

Court of Mobile County, Alabama, which judgment was

affirmed by the Supreme Court of Alabama on April 24,

1947. Taylor v. State, 249 Ala. 130, 30 So. (2d) 256. On

November 13, 1947, that Court denied petitioner permission

to file a petition for writ of error coram nobis in the trial

2

court, Ex Parte Taylor, 249 Ala. 670, 32 So. (2d) 659, which

decision was subsequently affirmed by this Court. Taylor

v. Alabama, — U. S. —, 92 L. ed. (Adv. Op. 1394).

In the majority opinion of this Court it was made clear

that the review of the judgment was limited to the pro

cedural question of whether or not the coram nobis remedy

as used in Alabama denied petitioner due process of law.

It was held that the procedure was in conformity with the

due process clause and that the Supreme Court of Alabama

did not deny petitioner due process by refusing permission

to file for coram nobis after taking into consideration the

entire record of the original trial along with certain photo

graphs produced by the State of Alabama and supported by

affidavit. The majority opinion, however, was careful to

point out that: “ If the new petition (seeking permission

to file petition for writ of error co-ram nobis) and its sup

porting affidavits stood alone or had to be accepted as

true, the issue would be materially different from what it

is.” Taylor v. Alabama, 92 L. ed. (Adv. Op.) at page 1401.

Mr. Justice F r a n k fu r te r in concurring pointed out that:

‘ ‘ In reaching such a conclusion the Supreme Court of Ala

bama was entitled to consider the circumstances of the

original trial, the manner of its conduct by the trial judge,

the professional ability with which the defendant was repre

sented, the behavior of the accused throughout the proceed

ings, and, in the light of all these circumstances, the weight

to be attached to the affidavits on which his present peti

tion is based.’ ’ Mr. Justice F r a n k fu r te r concluded: “ But

this merely carries me to sustaining the judgment of the

Alabama Supreme Court. There is not now before us any

right that the petitioner may have under the Judicial Code

to bring an independent habeas corpus proceeding in the

District Court of the United States.”

3

Mr. Justice M u r p h y in his dissenting opinion in which

Mr. Justice D ouglas and Mr. Justice R utledge concurred

pointed out that “ Fortunately, this Court has not yet made

a final and conclusive answer to petitioner’s claim. .

Nothing has been held which prejudices petitioner’s right

to proceed by way of habeas corpus in a federal district

court, now that he has exhausted his state remedies. He

may yet obtain the hearing which Alabama has denied

him. ’ ’

Thereupon, petitioner filed a verified petition for writ

of habeas corpus in the United States District Court for

the Middle District of Alabama (R. 1-5), and a rule to show

cause was issued by that court. The Attorney General of

the State of Alabama filed a pleading captioned “ Return

to Rule” (R. 8-9). This had the force and effect of a mo

tion to dismiss and was so recognized by the court and the

Attorney General of Alabama (R. 12). Under these cir

cumstances, the allegations of the verified petition had to

be accepted as true at that stage of the proceedings. A

hearing was held on the verified petition and the motion to

dismiss. Under normal procedure, such a hearing is limited

to legal arguments and was so limited in this case. No

pleadings were filed by the State of Alabama to bring to

issue the allegations in the verified petition. It cannot be

argued that at this stage of the proceeding, petitioner was

obliged to or should have been prepared to produce testi

mony.

Orderly procedure permits testimony only after the

i espondent has made a full and complete return and has

placed in issue the factual basis for the petition for writ of

habeas corpus. The record in the original trial was not

before the district court. Respondents had filed neither a

return within the accepted meaning of that term, nor an

answer, nor any denial of the factual basis for the petition.

4

The decision of the district judge was allegedly based upon

the legal insufficiency of the petition and was admittedly

determined by: (a) the verified petition, and, (b) the opin

ions of the Supreme Court of Alabama and of this Court

in the coram nobis case.

In applying to this Court for a writ of certiorari peti

tioner relied upon principles of law which heretofore had

been considered clear and well established:

a. Use by a state of a coerced confession to obtain a

conviction for a crime is a violation of the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Lee v. Mississippi, 322 U. S. 722;

Haley v. Ohio, 332 U. S. 596;

Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401;

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143 ;

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547;

Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 219;

Vernon v. Alabama, 313 U. S. 547;

White v. Texas, 310 U. S. 530;

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227;

Brown v. Mississippi, 313 U. S. 547.

b. A habeas corpus proceeding in the Federal District

Court is the proper method of attacking a conviction ob

tained in a state court in violation of defendant’s consti

tutional rights, after the exhaustion of state remedies.

White v. Hagen, 324 U. 8. 760;

Wade v. Mayo, 332 U. 8. 672;

House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 42;

a

Ex parte Hawk, 321 U. 8. 114;

Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U. S. 103;

Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2241-2255.

e. The allegations of a petition for habeas corpus in

Federal courts must be taken as true in the absence of an

answer or a hearing.

White v. Hagen, 324 U. S. 760;

House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 42;

Williams v. Kaiser, 323 U. S. 471;

U. 8. v. Adams, 320 U. S. 220.

d. The Federal District Court is under the duty to

forthwith award the writ of habeas corpus, unless it ap

pears from the petition itself that the party is not entitled

thereto.

Holiday v. Johnston, 313 U. S. 342;

Price v. Johnston, — U. S. — ; 92 L. ed. (Adv.

Op.) 993;

Von Moltke v. Gillies, 332 U. S. 708;

Marino v. Hagen, 332 U. S. 561;

U. 8. v. Adams, 320 U. S. 220;

Ex parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1;

Walker v. Johnston, 312 U. S. 275;

Title 28, United States Code, section 2243 (then,

28 U. S. C. #461).

e. The prior proceedings in this case did not relieve the

District Court of its duty to afford petitioner a hearing on

the allegations of the petition for habeas corpus.

House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 42;

Waley v. Johnston, 316 U. S. 101.

6

These principles of law heretofore considered clear and

well established are inextricably involved in this case. The

decision by an equally divided court has cast grave doubt

and confusion upon these principles.

The case was placed on the summary docket, thereby

limiting argument to one-half hour by one attorney. This

Court denied the request of attorneys for petitioner that

two attorneys be permitted to argue the case for a half

hour each. The respondent did not appear for argument so

that the entire argument was limited to one-half hour.

Less than a week after argument, the Court entered its

per curiam decision, affirming the judgment by an equally

divided court in this, “ a matter of life and death, a matter

of constitutional importance” . (Mr. Justice M u r p h y in

dissenting opinion.)

This case imperatively requires rehearing and final dis

position of the case by majority vote of this Court. This

case reached the Court by petition for certiorari, not on

appeal. The review thus came to petitioner because a suffi

cient number of this Court deemed the specific questions

presented to be of sufficient general importance to require

decision by this Court. The per curiam, order of affirmance

by an equally divided court fails to supply that decision.

Instead it leaves the law of this case in a state of confusion

and casts doubt on the applicability of the principle involved

to other cases.

For many decades, the practice has been followed, when

ever practicable, of having questions of the nature involved

in this case heard by the full court so that a judgment therein

might be by a majority of the Court. Brisko v. Common-

wealth Bank of Kentucky, 33 IT. S. (8 Pet.) 118; New York

v. Millan, 33 IT. 8. (8 Pet.) 120; Home Ins. Co. of New York

v. New York, 119 IT. 8. 129, 148; 122 IT. S. 636; 134 U. 8.

7

594; Polack v. Farmers Loan and Trust Co., 157 U. S. 429,

586; 158 U. S. 601.

Mr. Justice B la ck did not participate in either the hear

ing of argument or the decision in this case, and we respect

fully submit that for the reasons set out above, a rehearing

should be granted in this case in order to give to Mr. Justice

B lack an opportunity to reconsider his position in the light

of the equally divided Court so that the doubt and confusion

as to the principles of law involved may be resolved one

way or the other. The precedent for such action has been

recognized in the case of Hirota v. General MacArthur, 93

L. ed. (Adv. Op.) 119 and the granting of a rehearing in

the case of Marzani v. United States, — U. S. —, 93 L.

ed. —.

The opinion of this Court in the first Taylor case did not

pass upon the constitutional question as to whether or not

the conviction of Samuel Taylor was based upon a denial *

of due process of law. The decision of this Court in the

instant case leaves this question as well as the procedural

question in doubt. Unless these points are clearly decided

in this case they can never be decided. There is now no

other judicial remedy open to petitioner to prevent his death

by electrocution.

The per curiam order of the Court in this case does not

disclose the reasons for Mr. Justice B l a c k ’s nonparticipa

tion. Whatever they may be, petitioner is convinced that

if upon reconsideration Mr. Justice B la ck were to agree

to hear and participate in the decision of this case, petitioner

would thereby be afforded a full and complete hearing and

the possibility of a definitive determination of the issues

in this case so as to remove the doubt now existing as a re

sult of the present per curiam order. If Mr. Justice B lack

sits and hears argument on this case it might not be neces

sary for him to participate in the final decision in order to

8

have a majority decision. In the Hirota case, Mr. Justice

J ackson while agreeing to hear argument did not partici

pate in the final determination of the case because a ma

jority decision was possible without his participation.

Prior to the decision in this case the law was clear that,

after state remedies had been exhausted by a petitioner

without a hearing on the merits of claimed violations of the

Constitution, United States District Courts were prohibited

from dismissing a petition for habeas corpus sufficiently

alleging facts to show such constitutional violation without

a hearing on the merits. Ex Parte Hawk, supra, and White

v. Ragen, supra, and as modified by House v. Mayo, supra,

and Wade v. Mayo, supra. The order of this Court in the

instant case leaves an unresolved doubt, therefore as to the

present availability of habeas corpus upon the exhaustion

of state remedies in the process of which no hearing on the

merits was given. This doubt is particularly strong when

the opinion of the District Court herein and the opinion of

this Court in Taylor v. Alabama are considered together.

The order of this Court creates doubt concerning the

principle of the truth of uncontroverted facts in a Petition

for Writ of Habeas Corpus. From an examination of the

cases Walker v. Johnson, supra.; Waley v. Johnston, supra;

Holiday v. Johnston, supra; Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S.

458; Smith v. O’Grady, 312 U. 8. 329, it was clear that the

uncontroverted facts in a petition for writ of habeas corpus

to a federal court must be taken as true in the absence of

an answer or a hearing. In response to the rule to show

cause in the Court below, the State of Alabama did not sub

mit an answer nor was a hearing granted upon the facts of

the petition by the Court. There can be no question but

that the allegations of such petition, if true, sufficiently set

forth facts constituting a violation of constitutional rights

by a state court in the trial of the petitioner. The District

9

Judge, however, upon receipt of a motion to dismiss, which,

for all intents and purposes admits the truth of such allega

tions, refused to accept the allegations as true and without

more concluded rather “ that a further hearing is not re

quired by the Constitution of the United States” . (Italics

ours.)

The Court’s per curiam order of February 7, it is sub

mitted, places an unwaranted effect upon the decision in

Mooney v. Hollahan, supra, insofar as that case requires

that state courts, equally with federal courts, provide a

remedy whereby one claiming to have been convicted in

violation of basic constitutional rights may have such claim

judicially tested. The effect of the order of affirm

ance of this Court is to give the courts of Alabama the sole

jurisdiction for entertaining such applications according

to Alabama’s coram nobis standard.

The order of the Court in effect further completely bars

the remedy of and the standards of habeas corpus in the

federal courts in all circumstances to any person detained

by authority of an Alabama state court after disposal of

petition for permission to file for coram nobis. The order

fuither gives sanction to the Alabama coram nobis prac

tice of requiring a petitioner to prove his innocence as a

pi erequisite to obtaining a hearing on his claim of viola

tion of constitutional rights. Clearly, as pointed out in

petitioner’s brief and in argument before the Court, no

such rule had heretofore existed in the federal courts.

The order of the Court further gives sanction to Ala

bama’s practice of speculating on the verity of the allega

tions of a petition for coram nobis. While it may be ad

mitted that Alabama has the right to set up such procedure

as it may deem appropriate subject to the limitations of due

process for the consideration of claims such as the one

which petitioner makes, it is submitted that the intent of

the Mooney v. Hollahan doctrine was not to bar completely

10

the right to federal habeas corpus by a state prisoner, un

less he had obtained in the state court, through habeas

corpus, coram nobis or other similar procedure, a hearing

on the merits of his petition according to the standards

which prevail in the federal courts on habeas corpus.

In Waley v. Johnston, 316 U. S. 101, 104, this Court

stated: “ True, petitioner’s allegations in the circumstances

of this case may tax credulity. But in view of their spe

cific nature, . . . and the failure of respondent to deny . . .

them specifically, we cannot say that the issue was not one

calling for a hearing within the principles laid down in

Walker v. Johnston, 312 U. S. 275, 85 L. Ed. 830, 61 S. Ct.

574. . . . If the allegations are found to be true, peti

tioner’s constitutional rights were infringed.”

The decision of the District Court denied a hearing on

the merits and dismissed the petition on the grounds that

the issues had been disposed of in the coram nobis proceed

ings. Thus, instead of applying the standards for disposi

tion of habeas corpus proceedings in federal courts the Dis

trict Court substituted the contrary standards for state

court determination of coram, nobis applications. The fac

tual basis of the coram nobis proceedings was determined

by the decision.

The decision in this case now affirmed by an equally

divided court cannot be rationalized with the former opinion

of this Court in the coram nobis proceeding. There are

several clear principles of law involved in this decision which

cannot be rationalized with existing decisions.1 The equally

1 In a note concerning reversals by memorandum opinions it has

been stated that “ An opinion is a check on ‘administrative justice’

and doubtful reasoning. It makes possible the thoughtful extension,

limitation or correction of doctrine in subsequent cases. It is a guide,

in the present instance much needed, to counsel and inferior courts.

It is a mark of respect in case of reversal, for the court reversed. It

is submitted that in cases like the present, there are grave objections

to the Court’s departure from its practice of delivering opinions.”

A Memorandum Decision, 40 Harv. L. Rev. 485, January, 1927.

11

divided court and the lack of opinion thereby casts doubt

upon these principles of law. The present decision in this

case and the resultant confusion will increase rather than

decrease the applications to this Court for certiorari from

decisions of district courts.

The effect of the Court’s order is to completely bar peti

tioner’s right to a hearing with compulsory process and

right of cross examination in any judicial forum. Such a

consequence, it is submitted, is in and of itself a denial of

due process.

It cannot be said that petitioner’s claims are without

merit. There was a vigorous dissenting opinion in the

Alabama Supreme Court and in this Court on the coram

nobis proceeding. If petitioner is now electrocuted there

will always be grave doubt as to whether or not his life was

taken without due process of law. Our Constitution re

quires that due process of law be afforded at every step of

our judicial proceedings. Is it not more in keeping with our

principles to grant a full and complete hearing of this peti

tioner’s claim of denial of rights guaranteed by our

Constitution?

Conclusion

Petitioner has been seeking a hearing of his claim that

his conviction is in violation of the United States Consti

tution—a hearing within the accepted meaning of the word.

If he had been granted such a hearing the entire matter

would have been disposed of. If his claims were so un

believable the State of Alabama would not have opposed

such a hearing at every stage of both proceedings.

We are not unaware of the large number of petitions

for writs of habeas corpus in federal courts. On the other

12

hand, we are certain that the present decision by an equally

divided court will increase rather than decrease applica

tions to this Court for review of such cases.

Where a man’s life is at stake and constitutional rights

are involved his life should not be taken as the result of a

decision by an equally divided court based upon a half hour

argument.

W h erefore , petitioner prays that this Court grant to

petitioner a re-hearing by having the case placed on the

regular docket for a full hearing. Petitioner further prays

that Mr. Justice B la c k reconsider his reasons for not par

ticipating in this case and in the light of the equally divided

court that he participate in the hearing of argument and

if necessary the final decision of the case.

Counsel represents to the Court that this petition for

re-hearing and other relief is not filed for the purpose of

delay.

N esbitt E lm o re ,

Montgomery, Alabama,

T htjrgood M a r sh a ll ,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

F r a n k D . B eeves,

F r a n k l in H . W il l ia m s ,

C onstance B aker M o tley ,

R obert L . Carter ,

Of Counsel.

L a w y e r s P ress, I n c .. 165 William St., N. Y. C. 7; ?Phone: BEekman 3-2300

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STA TES

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 721

SAMUEL TAYLOR,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE OF ALABAMA

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E SUPREM E COURT OF T H E STATE

OF ALABAM A

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

E dward R . D u d le y ,

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

N esbitt E lm o re ,

Counsel for Petitioner.

A r t h u r D . S h ores ,

F r a n k l in H. W il l ia m s ,

Of Counsel.

« *

r 1' i j '><V ^ .«[

i

,! # r 'r r 1 V

/ > | }■r\. -■> ■■ y / s'; 7- Vt\x'V( > /.. >_ • v. . :

, I

r t-S .'- • 4./X% \ r j ■■ ■'■■ • -V - '- - I ••’ " ' ; / : v'V/y.v (Ay'/f t -- S • v ; :~ 'S., i *' -*i ■

S ' s:

1' V ^ !

-K-Y \ ' / AV,v v ;-&V M

y > ,5

-'t a,

,‘W \ * V-

m ;

SB 'y ■

M

\ ' ' T? vV

: Y ;■ '

:l!' •.. n\r

' r ' ? r,i

■

INDEX

T able of C on ten ts

Page

Opinion of court below ................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................... 1

Summary statement of matter involved................... 2

1. Statement of ca se .............................................. 2

2. Statement of fa c ts ............................................ 3

Question presented....................................................... 5

Errors relied upon ....................................................... 6

Outline of argument...................................................... 6

Summary of argument.................................................. 6

Argument ....................................................................... 7

I. The Supreme Court of Alabama erred in deny

ing petitioner’s motion for leave to file a

petition for a writ of error coram nobis. . . . 7

A. The conviction of petitioner through

the use of a confession extorted by

force, violence and fear is a violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment......... 7

B. The refusal to permit petitioner to file

a petition for a writ of error coram

nobis to raise this question and to

introduce testimony in support

thereof at a hearing free from fear

was a denial of due process............... 8

Conclusion ..................................................................... 13

T able of C ases

Ashcraft v. Tennesse, 322 U. S. 143............................ 8

Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278............................ 7

Canty v. Alabama, 309 U. S. 629.................................. 7

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227............................ 7

Carter v. Illinois, 329 U. S. 173.................................... 13

Ex Parte Burns, 22 So. (2d) 517.................................. 8

Ex Parte Lee, 27 So. (2d) 147...................................... 8

Haley v. Ohio, 92 L. E d .— ............................................ 8

—6031

11 INDEX

Page

Eysler v. Florida, 315 U. S. 411.................................. 12

Johnsons. Williams, 13 So. (2d) 683........................ 8

Lee v. Mississippi, 92 L. E d .— .................................... 8

Lisenba v. California, 314 IT. S. 219............................ 7

Lomax v. Texas, 313 IT. S. 544.................................... 7

Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322 IT. S. 596................................ 8

Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401............................ 8

Marino v. Ragen, 92 L. Ed. — .................................... 9

Mooney v. Holohan, 294 IT. S. 103................................ 8

Pyle v. Kansas, 317 IT. S. 2 13 ...................................... 11

Redus v. Williams, 13 So. (2d) 5 6 1 ............................ 8

Rice v. Olsen, 324 U. S. 786........................................... 11

Taylor v. State, 32 So. (2d) 659.................................... 8

Tompkins v. Missouri, 323 IT. S. 485 .......................... 10

Vernon v. Alabama, 313 IT. S. 547 .............................. 7

Ward v. Texas, 316 IT. S. 547 ........................................ 7

White v. Texas, 309 U. S. 631, 310 IT. S. 530................. 7

Williams v. Kaiser, 323 IT. S. 471................................ 10

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 721

SAMUEL TAYLOR,

vs.

Petitioner,

STATE OF ALABAMA,

Respondent.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

The majority and dissenting opinions of the Supreme

Court of Alabama appear in the record filed in this cause

(R. 16-28) and are reported at------Ala.------ , 32 So. (2d) 659.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Sec. 237(b)

of the Judicial Code (28 U. S. C. 344(b)), as amended

February 13, 1925.

The date of judgment was the 4th day of December 1947,

on which date the Supreme Court of Alabama overruled

petitioner’s application for rehearing in this cause (R. 30),

after said court had, on the 13th day of November 1947,

denied petitioner’s application for leave to file a petition

for writ of error coram nobis in the Circuit Court of Mobile

2

County, Alabama (R. 28). Petition for certiorari was filed

on March 3, 1948 and was granted by this Court on April 5,

1948 (R. 31).

Summary Statement of Matter Involved

1. Statement of Case

Petitioner, Samuel Taylor, an ignorant Negro youth, was

charged with having committed the crime of rape of a white

girl; was tried, convicted and sentenced by the Circuit Court

of Mobile County, Alabama, on the 19th day of November

1946. Judgment and sentence of death was imposed upon

petitioner on the 19th day of November 1946. Petitioner is

now confined in an Alabama state penitentiary under sen

tence of death, pursuant to the said judgment.

On the 24th day of April, 1947, the Supreme Court of

Alabama affirmed the judgment of the Circuit Court of

Mobile County, Alabama.

On September 18,1947, petitioner applied to the Supreme

Court of Alabama for leave to file an application for writ

of error coram nobis before the Circuit Court of Mobile

County, Alabama (R. 1). The petition and supporting

affidavits alleged that the confession upon which petitioner’s

conviction was based was extorted by force and violence

exerted against him by state officers; that he was ignorant

of his rights at the time of trial and because of fear of

reprisals did not advise his court-appointed attorney that

the said confession was so extorted; that petitioner’s new

attorney was not advised of these facts until after peti

tioner’s conviction, the preparation and filing of the motion

for new trial, the overruling of said motion by the Circuit

Court of Mobile County, Alabama, the appealing of peti

tioner’s case and the docketing of same and the decision

of said Supreme Court of Alabama as aforesaid (R. 1-11).

3

The State of Alabama moved to dismiss the said petition

and the issue was thus submitted for determination of the

court (R. 11-15). The Supreme Court of Alabama denied

the application, holding that:

1) The proposed attack on the judgment lacked

merit; and

2) The allegations of the petition were unreasonable

and there was no probability of truth therein (R. 16-20).

3) Petitioner did not testify in the original trial and

the petition did not contain a “ positive statement of

denial of guilt or present protestation of innocence.”

The dissenting opinion pointed out that the writ of error

coram nobis was proper to reach facts which were unknown

to the court when judgment was pronounced and which the

petitioner was prevented from presenting because of duress,

fear or other sufficient cause and that in this case “ the

petition considered in the light of the record shows a reason

able probability of the truth of the allegations in the peti

tion and entitles petitioner to leave to seek relief in the trial

court” (R. 20-28).

In this Court, petitioner asserts that his constitutional

right to due process of law was violated by the action of the

Supreme Court of the State of Alabama in denying him

permission to file an application for writ of error coram

nobis in the Circuit Court of Mobile County, Alabama.

2. Statement of Facts

The details surrounding the obtaining of the alleged con-.

fession from petitioner, upon which his conviction below

was based, appear in the petition for writ of error coram,

nobis and the supporting affidavits (R. 1-11). Counsel for

petitioner representing him on the filing of his petition for

leave to file an application for writ of error coram nobis did

4

not represent Mm at Ms trial in the Circuit Court of Mobile

County, Alabama. Petitioner, as alleged in Ms petition

to the Supreme Court of Alabama, because of fear of bodily

harm, failed to inform the attorney representing him at

his trial of the circumstances surrounding the obtaining of

the said alleged confession (R. 4). The said attorney could

not have known of these facts by the exercise of reasonable

diligence in time to have presented them to the trial court

(R. 4). After final affirmance of his conviction by the

Supreme Court of Alabama, petitioner’s present counsel

was requested to intervene. Petitioner’s present attorney

obtained affidavits supporting petitioner’s allegations of

cruel and inhuman treatment from three other individuals

who were arrested and confined at the same time as peti

tioner. These affidavits were submitted in support of his

petition to the Supreme Court of the State of Alabama

(R. 6, 8, 10). The petition and affidavits showed that peti

tioner and three (3) other Negro youths were arrested by

police in Prichard, Alabama, near midnight on the night

of June 29, 1946 (R. 2). They were taken to the City Jail

at Prichard, Alabama, and subjected to cruel, brutal and

inhuman treatment by several police officers in an attempt

to obtain from them a confession to having committed a

robbery. The other three Negro youths were detained in

the City Jail without further molestation for several days.

Petitioner, however, was subjected to continuous beating

and mistreatment by police officers of the city of Prichard

for a period of four consecutive nights. The purpose of

the said beatings and questioning was to force petitioner

to confess to an alleged rape which the said police officers

accused him of having committed (R. 2-3).

After this mistreatment continued for a period of four

nights, petitioner, in great fear for his life, health and

safety, confessed to having committed the crime of rape.

He was told at this time by these officers that if he made

5

mention of the fact that he had been beaten and mistreated,

he would be subjected to even more beatings and mistreat

ment. After having made such confession, a group of out

side responsible people of the community, who were without

knowledge of the gross brutality and mistreatment to which

petitioner had been subjected, was brought into the jail at

Prichard, Alabama, at 3 o ’clock on the morning of July 3,

1946, where petitioner was coerced through fear of further

reprisals to again confess in the presence of these people

in a staged, prearranged atmosphere (R. 3).

As stated in his petition, “ Petitioner was put in such

great fear for his future safety after having been sub

jected to such mistreatment * * *, and after having been

threatened with even worse physical mistreatment by the

police officers # * * if # * * (he) # # * did mention

said beatings to any person, that he failed and refused by

reason of such fear to mention this mistreatment and ex

tortion of said confession from him to his attorney who

was appointed by the Court to defend him * * * ” (R. 4).

In spite of the strong prima facie case set forth by the

petitioner in his petition and supporting papers presented

to the Supreme Court of Alabama, permission to apply

for a writ of error coram nobis in the Circuit Court of

Mobile County, Alabama, was denied by a divided court

(R. 28).

Question Presented

Whether, in view of the facts alleged in the petition and

supporting affidavits submitted to the Supreme Court of

Alabama, the denial of opportunity to the petitioner to

apply for a writ of error coram nobis to the court convict

ing him constituted a violation of petitioner’s constitutional

rights as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

6

Errors Relied Upon

The Supreme Court of Alabama erred:

In denying petitioner’s application for leave to apply

for a writ of error coram nobis to the Circuit Court of

Mobile County, Alabama, and:—

a) In bolding that the facts contained in the said

application and supporting affidavits were not rea

sonable ; and,

b) In bolding that said allegations lacked the

probability of truth; and,

c) In giving weight to the failure of petitioner to

testify at bis trial and to affirmatively allege bis

innocence in bis petition.

Outline of Argument

I

The Supreme Court of Alabama erred in Denying Peti

tioner’s Motion for Leave to File a Petition for a Writ of

Error Coram Nobis.

A. The conviction of petitioner through the use of a

confession extorted by force, violence and fear is a vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

B. The refusal to permit petitioner to file a petition

for a writ of error coram nobis to raise this question

and to introduce testimony in support thereof at a

hearing free from fear was a denial of due process.

Summary of Argument

Petitioner herein asserts that his constitutional right to

the due process of law has been denied by the action of the

Supreme Court of Alabama in dismissing his petition for

permission to file a writ of error coram nobis with the court

convicting him.

7

Petitioner’s conviction was based upon an alleged con

fession obtained by officers of the State of Alabama through

the unlawful use of force, duress and intimidation, as stated

by this Court in a long line of cases outstanding among

which is Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227.

The State of Alabama has recognized the writ of error

coram nobis as a form of relief available to individuals

unlawfully confined. The denial of the substance of relief

to petitioner without opportunity given him to submit proof

in support of the allegations contained in his petition for

permission to file a writ of error coram nobis has deprived

him of his due process of law.

Argument

The Supreme Court of Alabama Erred in Denying Peti

tioner’s Motion for Leave to File a Petition for a Writ of

Error Coram Nobis.

A. The Conviction of Petitioner through the Use of

a Confession Extorted by Force, Violence and Fear is

A Violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The principle referred to by this Court in the case of

Hysler v. Florida,1 that conviction upon a confession ‘ ‘ wrung

from an accused by overpowering his will, whether through

physical violence or the more subtle forms of coercion com

monly known as ‘ the third degree’ ” is offensive to our

constitutional guarantee of due process and violates “ civil

ized standards for the trial of guilt or innocence” is funda

mental in our law. The principle has been reiterated by

this Court in a long and unbroken line of decisions.2 The

1 315 u. S. 411, 413.

2 B row n v. M ississipp i, 297 U. S. 278; C ham bers v. F lorid a , 309 U. S.

227; C anty v. A labam a, 309 U. S. 629; W h ite v. T exas, 309 U. S. 631,

310 U. S. 530; L om a x v. T exa s , 313 U. S. 544; V ern on v. A labam a, 313

U. S. 547; L isen ba v. C aliforn ia , 314 U. S. 219; W a rd v. T exa s , 316 U. S.

8

principle is controlling even though the alleged confession

is not the sole basis for the conviction.3

B. The Refusal to Permit Petitioner To File a Peti

tion for A Writ of Error Coram Nobis to Raise this

Question and to Introduce Testimony in Support

Thereof At a Hearing Free from Fear Was a Denial

of Due Process.

Assuming the truth of the allegations contained in the

petition before the Supreme Court of Alabama herein

(E. 1), which assumption was effected by the state’s motion

to dismiss,4 there can be no dispute that the principle dis

cussed above is applicable to petitioner’s conviction. The

validity of this principle was recognized by the Alabama

Supreme Court (R. 17) yet permission to file application for

writ of error coram nobis was denied petitioner.

Though the common-law writ of error coram nobis was

adopted by the State of Alabama,5 6 pursuant to the mandate

of this Court contained in the case of Mooney v. Holohanf

its relief has usually been denied to petitioners seeking

hearings after conviction on alleged constitutional viola

tions occurring during trial.7

The State of Alabama has established the rule that habeas

547; A sh cra ft v. T ennessee, 322 U. S. 143; L y o n s v. Oklahom a, 322 U. S.

596; M alinski v. N ew Y o rk , 324 U. S. 401; L ee v. M ississip p i, 92 L. Ed,

—; H a ley v. Ohio, —, 92 L. Ed. —.

3 M alinski v. N ew Y ork , supra , L ee v. M ississipp i, supra.

4 “The effect of the motion to dismiss is to confess the truth of the allega

tions of the petition for the purpose of said motion.” Dissenting opinioa.

T aylor v. S tate, 32 So. (2d) 659 (R. 23).

5 Johnson v. W illiam s (1943), 13 So. (2d) 683.

6 294 U. S. 103.

1 J ohnson v. W illiam s, su p ra ; R ed os v. W illiam s (1943), 13 So. (2d)

561; E x P a rte B urns (1945), 22 So. (2d) 517; E x P a rte L ee (1946), 21

So. (2d) 147.

9

corpus will lie only where the invalidity of the judgment

appears on the face of the record of the trial.8

In Alabama the only procedure available to challenge

a judgment on the grounds of facts not appearing on the face

of the record is by means of a petition to the Supreme Court

of Alabama for leave to petition the Circuit Court where

the conviction was obtained for a writ of error coram nobis

to review the judgment.9

If the requirements for the granting of this form of relief

are so strict as to require refusal of relief in a case where

the constitutional violation is as clearly alleged as herein,

then the remedy offers “ no substantial hope of relief.” 10

As stated by this Court in discussing the “ procedural

labyrinth” obtaining in the State of Illinois:

“ . . . the remedies available there are inadequate.

Whether this is true because in fact no remedy exists,

or because every remedy is so limited as to be inade

quate, . . . is beside the point. If the federal

guarantee of due process in a criminal trial is to have

real significance, . . . it is imperative that men con

victed in violation of their constitutional rights have

an adequate opportunity to be heard in court. ’ ’ 11 (Ital

ics ours.)

No such “ adequate opportunity” for a hearing in court

has been given petitioner in this case.

The statement contained in the dissenting opinion below

accurately reflects petitioner’s position before this Court:

“ If the petitioner in his application must affirm his

innocence and make proof rebutting the implications

of guilt arising from the judgment of conviction pro

cured by use of coerced confessions before he can

s V ern on v. S ta te , 240 Ala. 577, 200 So. 560; John son v. W illiam s

supra.

9 Johnson v. W illiam s, supra.

10 M arino v. H agen , 92 L. Ed. —.

11 M arino v. H agen, supra .

10

obtain leave to file a petition for the writ of error

coram nobis to establish want of due process under

the Constitution, as the majority opinion holds, the

guarantees of the Constitution become as ‘ sounding

brass and tinkling cymbal’—mere platitudes—without

force or substance and a defendant put on the ‘ rack’

and forced to confess his guilt is without remedy or

hope.”

There was no direct conflict between the allegations

contained in the petition before the Alabama Supreme

Court and the facts of the record. At petitioner’s trial,

no proof was offered as a predicate for the introduc

tion of the alleged confession. Eather, there was merely

a lack of proof of duress because the effect of the same

coercion and intimidation used to force the confession from

petitioner still made itself felt upon him.

The petition submitted to the Alabama Supreme Court

‘ ‘ establishes on its face the deprivation of a federal right. ’ ’ 12

It is submitted that instead of offering a remedy therefor,

the Supreme Court of Alabama, through its refusal to grant

permission for the filing of an application for writ of error

coram nobis, deprived petitioner of his only avenue of relief

from this unconstitutional conviction “ without giving peti

tioner an opportunity to prove his allegations. ’ ’ 13 This

denial has deprived petitioner of relief even in the federal

courts as such courts ordinarily do not entertain habeas

corpus proceedings setting forth substantially the same

facts as have been previously brought before a state court

by writ of error coram nobis or in an habeas corpus pro

ceeding.

The Alabama Court erred in denying petitioner relief

on the grounds that some testimony appeared in the record

that the confession was voluntary and that petitioner had

12 W illiam s v. K a iser , 323 U. S. 471.

13 W illiam s v. K a iser , su p ra ; T om pkin s v. M issouri, 323 U. S. 485.

11

failed to testify at the original trial. As stated by Mr.

Justice Murphy in the case of Lee v. Mississippi, supra.

“ . . . And since our constitutional system permits

a conviction to be sanctioned only if in conformity with

those principles, inconsistent testimony as to the con

fession should not and cannot preclude the accused

from raising the due process issue in an appropriate

manner. . . . Indeed, such a foreclosure of the right

to complain ‘ of a wrong so fundamental that it made

the whole proceeding a mere pretense of a trial and

rendered the conviction and sentence wholly void,’ . . .

would itself be a denial of due process of law.”

Petitioner’s papers were sufficient to constitute a prima

facie case and require the granting of permission to apply

for the writ, followed by a hearing in substantiation of the

allegations.14

14 “Habeas corpus is a remedy available in the courts of Kansas to

persons imprisoned in violation of rights guaranteed by the Constitution

of the United States. Petitioner’s papers are inexpertly drawn, but they

do set forth allegations that his imprisonment resulted from perjured tes

timony, knowingly used by the State authorities to obtain his conviction,

and from the deliberate suppression by those same authorities of evidence

favorable to him. These allegations sufficiently charge a deprivation of

rights guaranteed by the Federal Constitution, and, if proven, would en

title petitioner to release from his present custody. They are supported

by the exhibits referred to above, and nowhere are they refuted or denied.

The record of petitioner’s conviction, while regular on its face, manifestly

does not controvert the charges that perjured evidence was used, and

that favorable evidence was suppressed with the knowledge of the Kansas

authorities. N o d eterm ination o f the v er ity o f these a llegations ap pea rs

to have been made. The case is therefore remanded for further proceed

ings. ’ P y le v. K an sas, 317 U. S. 213 (1942) (italics ours).

Whatever inference of waiver could be drawn from the petitioner’s

plea of guilty is adequately answered by the uncontroverted statement

in his position that he did not waive the right either by word or action.

J’his . . . squarely raised a question of fact . . . A defendant

who pleads guilty is entitled to the benefit of counsel, and a request . . .

is not necessary. It is enough that a defendant . . . is incapable

adequately of making his defense . . . W h eth er all th ese conditions

exist is a matter which must be determ ined) b y ev id en ce w h ere th e fa c ts

are in d ispute.” P ic e v. Olsen, 324 U. S. 786 (1945) (italics ours).

12

While the majority of this Court in the H ysler15 case

sustained the state court’s refusal to issue the order, the

case is easily distinguishable from the instant case, and

in fact the instant case falls within the offensive violations

of constitutional guarantees as outlined by Mr. Justice

Frankfurter for the majority in stating guides for decisions

of this nature. In the Hysler case, petitioner in alleging

denial of due process four years after conviction based his

claim for relief on the recantation of one of the witnesses

against him. In commenting upon this basis for petitioner’s

relief, this Court stated:

“ Hysler’s claim before the Supreme Court of Florida

was that Baker repudiated his testimony insofar as it

implicated Hysler and that he now named another man

as the instigator of the crime. Considering the fact that

this repudiation came four years after leaden-footed

justice had reached the end of the familiar trail of

dilatory procedure, and that Baker now pointed to an

instigator who was dead, the Supreme Court of Florida

had every right and the plain duty to scrutinize this

repudiation with a critical eye, in the light of its famil

iarity with the facts of this crime as they had been

adduced in three trials, . . . ”

The instant case is clearly distinguishable from the above

in that, far from presenting a collateral attack upon the

judgment of the court, petitioner alleges that he personally

was brutally beaten, intimidated and coerced by state officers

to the point of not only confessing to a crime which he did

not commit but to such a degree that the fear for his life

sealed his lips in communications with his court-appointed

attorney. In addition, petitioner in his application for

writ of error coram nobis filed at the earliest possible time

15 H ysler v. Florida , 315 U. S. 411 (1942).

13

presented the affidavits of three other persons arrested with

him, all of whom alleged substantially the same set of facts

surrounding the mistreatment accorded petitioner while in

the custody of state officers. There is no question of recan

tation of perjured testimony here but rather a request for

an opportunity to be heard for the first time at a time and

a place not permeated with fear, intimidation and threats

for one’s safety which, in itself, is the very essence of due

process.

The denial to petitioner of this opportunity for a hearing

upon his allegations constitutes reversible error requiring

remedial action by this Court.

Conclusion

The State of Alabama, while purporting to follow the

requirements of due process as set forth by this Court in

Mooney v. Holohan, supra, has by practice, effectively

denied to petitioner the very type of corrective judicial

process required by this Court.

The life of an American citizen hangs in the balance.

This Court should, in view of this, “ insist upon the fullest

measure of due process.’ ’ 16 If the petitioner is denied the

opportunity to present proof of the denial of his constitu

tional right to due process, then as stated by Justice Brown

in his dissenting opinion below:

“ Guarantees of the Constitution become as ‘ sounding

brass and tinkling cymbal’. ”

It is respectfully requested that this Court reverse the

decision of the Supreme Court of the State of Alabama 18

18 Carter v. Illinois, 329 U. S. 173.

14

denying petitioner leave to apply for a writ of error coram

nobis to the Circuit Court of Mobile County, Alabama.

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

N esbitt E lm o re ,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

E dward E . D udley ,

A rth u r D. S hores,

F r a n k lin H . W illiam s ,

Of Counsel.

(6031)

/ , $5 1 m 7 V * ^ t ; \ <z j :O - ‘t>h \

, i Si 1 < i

• :* '■' ,'lS I

■'4i>

;-V; '.S, )SS»S-. / t '■ ’ V % t ' "

■ ; S 7. \ 0 ,C J i

I f i S M S S I M t l f t | w 7% t

f t # # K i i f

| |

' 9 ^ 1 p

/ , < ' f (r V V̂ \ '. -s> ft-

--

■ y. < ' • f t -

/ / U 'S # - f t# ‘ : v#

.;•. ,.-0

S * s

'1 # /< ':.'! A ,'■,A Sy ' -' A'f' " f t

\

■:' y y f #

S v 4 v / S , . S . ' * t .

S Y

* K y . > .S (>

■ , \ ; 1 #

<• : • > u f t

i# -

. ■ Sv, j ' r , / * ; yj'~- 1 ^

A ..ft.K :i

-s,pf oy , A - 'S / ; v . y

'’l ;

f t i v #

-fe sn

.

i v ‘s ; S f v s

• - f t #

# f e 3 P I S’ ;S4’f \ v.S.y. 1 f

-,)A 5 > j ' / J,‘' ' \ *

' t . T . #

r ( 1 0

V - * r

\ < ( 1 ft f t- \A ' ft a

' ' ; 3 j }i W*-f> !h ' v , i t > <' V, ,1 ' V . ^

? 1 ft > ">f#

:';4 i f t ;',/..x y ftft ; - - . ' f t ^ . f t

f t 1 ■ .\. - ' . r

r

7>.i ■ - !V,i'

■

7' Jfes |

'

S' ;v.< H : . E. fii ArK S « K » * a

V ' J , ’

-V" M v

T , , - S :

̂ Jjf: fti

IftftSImTV}!

' I S* • v| -"v;® ;MrY T- ' L-\ SV. ‘S.

ftft: ® ft' A i ' ,f r ' , ,/*«;

A##/*' ft 3>'

;| >V . v . fK

’ ^ t V *

‘ I #. - ! -

.V5

His ,

, ' ■

> s 7 ’ ■■■'■■■■■... *.’^Vru"

7 . f t f t f t

■•Shi-; ■ ft < \ Tfc-

■ ■■ vw : i

- '■ > f t '

&? v

ft' / ■■

ft 3ft

■t. -~ t * s . -1 V M

*r

ftft

/ M IS: -a;;

»ir ■

> / ' ! ' , •' f t f t ' ■ r >4 ' ’

f t • - .f t . - f t

c-®- - ■ -V/

7 ; ^;,Vi '■■{-

"! li V, - •.1;'■ ^ A;

1. J f5̂

| •} ':

! ‘ . V '

m m # -

•A'r

% ' \

UISj... ,..M,.

^ i ' »■* V^ , f \

* r , ■ 11 ' JA;. <

: i’ ' / ' " ,

̂'•: • fe.rR. £

SUPREME EOURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1948

No. 121 Miscellaneous

SAMUEL TAYLOR,

vs.

Petitioner,

TENNYSON DENNIS, W a r d e n A l a b a m a - S t a t e P e n i

t e n t i a r y , K i l b y , A l a b a m a , .

Respondent

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

N e s b i t t E l m o r e ,

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l ,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

F r a n k D. R e e v e s ,

F r a n k l i n H. W i l l i a m s ,

Of Counsel.

INDEX

C a s e s C i t e d

P age

Anderson v. United States, 318 U. S. 350..................... 9

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143............................. 6, 9

Brown v. Mississippi, 313 IT. S. 547.............................. 6, 9

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227.............................. 6, 8

Ex parte Hawk, 321 IT. S. 114........................................ 7,10

Ex parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1 .......................................... 7

Ex parte Taylor, 249 Ala. 667, 32 So. 2d 659............ 2, 4,16

Frank v. Mangum, 237 U. S. 309.................................... 9

Haley v. Ohio, 332 IT. S. 596.......................................... 6, 8

Holiday v. Johnston, 313 IT. S. 342............................. 7, 8, 21

House v. Mayo, 324 IT. S. 42................................... 7, 8,10,19

Lee v. Mississippi, 332 IT. S. 722.................................... 6, 8

Lisenba v. California, 314 IT. S. 219............................ 6, 9

Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401............................ 6, 8

Marino v. Hagen, 332 IT. S. 561...................................... 7

McNabb v. U. S., 318 IT. S. 332...................................... 9

Mooney v. Holohan, 294 IT. S. 103................................ 7, 9

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S. 86.................................... 10

Price v. Johnston, 334 IT. S. 266........................ ■ 7

Re 620 Church St. Building Corp., 299 IT. S. 24......... 8

Steffler v. United States, 319 IT. S. 38.......................... 8, 21

Taylor v. Alabama, 335 IT. S. 252 ............................... 3, 5,17

Taylor v. State, 249 Ala. 130, 30 So. 2d 256................. 2

United States v. Adams, 320 IT. S. 220......................... 7,11

Vernon v. Alabama, 313 U. S. 547................................ 6, 9

Von Moltke v. Gillies, 332 IT. S. 708............................ 7

Wade v. Mayo, 332 U. S. 672........................................ 7,10

Waley v. Johnston, 316 IT. S. 101.................................. 8,16

Walker v. Johnston, 312 U. S. 275............................. 7,12,16

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547 ........................................ 6, 9

Wells v. United States, 318 IT. S. 257............................ 8, 21

White v. Hagen, 324 IT. S. 760........................................ 7,10

White v. Texas, 310 U. S. 530........................................ 6,9

Williams v. Kaiser, 323 IT. S. 471................................ 7,11

S t a t u t e s C i t e d

Title 28, United States Code, section 1651(a)............. 8

Title 28, United States Code, sections 2241-2255....... 7,10

— 339

OCTOBER TERM, 1948

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 121 Miscellaneous

SAMUEL TAYLOR,

vs.

Petitioner,

TENNYSON DENNIS, W a r d e n A l a b a m a S t a t e P e n i

t e n t i a r y , K i l b y , A l a b a m a ,

Respondent

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinion of Court Below

Neither the opinion of the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Alabama nor the order of the

United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit has been reported officially. The District Court opin

ion appears at pages 9 and 10 of the Record and the Order

of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals appears on

page 14 of the Record.

Jurisdiction

I

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title

28 United States Code, Section 1651 (a).

The date of judgment in the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Alabama is July 7, 1948 (R. 9-10).

2

The date of the order denying a certificate of probable cause

for an appeal to the United States Circuit Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit, issued by the said United States Dis

trict Court, is July 17, 1948 (R. 12). The date of the

order of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit denying a petition for a certificate of prob

able cause for an appeal to that court, is July 12, 1948 (R.

14). Motion for leave to file petition for writ of certiorari

and petition for certiorari were duly presented to this

Court on September 14, 1948 and were granted by this

Court on December 13, 1948 (R. 15).

Summary Statement of Matter Involved

1 . S t a t e m e n t o f t h e C a s e

Petitioner, an ignorant Negro, nineteen years of age

at the time of his trial, was convicted of the crime of rape

and sentenced to death by electrocution by the Circuit Court

of Mobile County, Alabama on November 19, 1946. Upon

appeal, the Supreme Court of Alabama on April 24, 1947

affirmed this judgment. Taylor v. State, 249 Ala. 130, 30

So. 2d 256.

On September 18, 1947, petitioner through new counsel

petitioned the Supreme Court of Alabama for permission to

file a petition for writ of error coram nobis in the trial

court. This sworn petition with supporting affidavits

alleged that the conviction was based upon confessions

obtained through the use of force, duress and intimidation

by police officers of the state. On November 13, 1947 the

petition was denied. Ex Parte Taylor, 249 Ala. 667, 32

So. 2d 659.

Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama was granted

by this Court on April 5, 1948. Taylor v. Alabama, 333

U. S. 866.

3

On June 21, 1948, this Court affirmed the judgment of the

Supreme Court of Alabama. Taylor v. Alabama, 335 U. S.

252.

On July 6, 1948, petitioner filed a petition for writ of

habeas corpus in the District Court of the United States

for the Middle District of Alabama (R. 1-5); a rule to show

cause was thereupon issued to respondent (R. 5).

On July 7, 1948 respondent filed a motion to dismiss.

(R. 8-9) On the same day the court dismissed the petition

without requiring a return, granting a hearing or taking

testimony, (R. 9-10) and immediately thereafter denied an

oral motion for a certificate of probable cause (R. 12).

Subsequently, a written petition for a certificate of prob

able cause, addressed to the United States Circuit Court

of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, filed on July 16, 1948 (R.

13) was denied by Leon McCord, one of the judges thereof

(R, 14).

On July 17, 1948, petitioner filed a written motion for

a certificate of probable cause in the District Court (R.

11) which was denied on that same date (R. 12).

Petition for certiorari was granted by this Court on

December 13, 1948. Taylor v. Dermis, Oct. Term, 1948, No.

121 Misc., — U. S. —.

2 . S t a t e m e n t o f F a c t s

The facts of the case are set out in the petition for writ of

habeas corpus (R. 1-5). It is therein alleged that peti

tioner is at the present time detained and imprisoned by

Tennyson Dennis, Warden of the Alabama State Peniten

tiary, Kilby, Alabama, under sentence of death by electro

cution by virtue of a judgment of the Circuit Court of Mo

bile County, Alabama, rendered on November 19, 1946, on

a conviction of rape; that the said judgment and conviction

was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Alabama on April 24,

4

1947, and reported at 30 So. (2d) 256; that petitioner was

arrested by police officers of the City of Prichard, Alabama,

on June 29, 1946; that he was beaten, threatened and co

erced by said officers for a period of three days until he

made a confession to a rape charge; that said confession

was later introduced in evidence on the trial of his case in

the Circuit Court of Mobile County, Alabama, but that due

to ignorance of his rights and the fear of reprisals in which

he was placed by the threats of these police officers, he failed

to mention the coerced nature of said confession to his

attorney, who was first appointed to represent him at said

trial, and that consequently no evidence as to the involun

tary nature of said confession was introduced on his behalf

in said trial.

The petitioner further alleged that after his conviction

and the affirmance of the judgment of conviction as afore

said, petitioner’s family employed new counsel to repre

sent him, which counsel discovered evidence as to the invol

untary nature of said confession and on the basis thereof

filed in the Supreme Court of Alabama a petition for leave

to file a petition for a writ of error coram nobis in the Cir

cuit Court of Mobile County, Alabama, to inquire into the

involuntary nature of said confession; that on the 13th day

of November, 1947, the Supreme Court of Alabama (one

justice dissenting) denied said petition, and further denied

without opinion an application for rehearing on December

4, 1947 (Ex Parte Taylor, 249 Ala. 667, 32 So. 2d 659).

The petition alleged that subsequently, petitioner filed a

timely application to this Court for certiorari claiming

that due process of law’ had been denied him by virtue of

the decision of the Supreme Court of Alabama in refusing

permission to petitioner to file for a wrrit of error coram

nobis in the Circuit Court of Mobile County, Alabama; that

certiorari was granted on April 5,1948 (Taylor v. Alabama,

£66); that on June 21, 1948, this Court affirmed

5

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama, holding

that petitioner’s rights to due process of law had not been

violated by the action of the Supreme Court of the State of

Alabama (Taylor v. Alabama> 335 U. S. 252).

In spite of the uncontroverted allegations of the petition

for habeas corpus, the District Court dismissed said peti

tion without requiring a return or a hearing. Petitioner

has exhausted all of the judicial remedies available to him,

both in the Alabama courts and in the lower United States

courts, and has not yet obtained a hearing on the allegations

set forth in his petition for writ of habeas corpus.

Question Presented

IS A FEDERAL DISTRICT COURT JU STIFIE D , AFTER ISSUING A RULE

TO SHOW CAUSE, IN DISM ISSING AN UNCONTROVERTED PETITION

FOR HABEAS CORPUS IN T H E ABSENCE OF AN AN SW ER OR A

HEARING, W H IC H PE TITIO N SU F FIC IE N T LY ALLEGES DEPRIVA

TION BY A STATE C R IM IN A L COURT OF P E TIT IO N E R ’ S CONSTI

TUTIONAL RIGH TS, ON TH E GROUNDS T H A T TH E FACTS AS A L

LEGED TH E R E IN W ERE PREVIOUSLY HELD BY TH E ST A T E ’ S

HIGHEST COURT TO BE IN SU FFIC IE N T TO INVOKE CORAM NOBIS,

THE ONLY AVAILABLE STATE REM EDY, AND T H A T T H IS COURT

FOUND TH A T SU C H REFUSAL TO GRANT CORAM NOBIS W AS NOT

A DENIAL OF DUE PROCESS ?

Errors Relied Upon

I

The Federal District Court erred in dismissing the un

controverted petition for habeas corpus.

6

(

II

The Federal District Court erred in holding that a hear

ing on the habeas corpus petition was not required by the

United States Constitution because:

A. The same issues were inquired into by the Su

preme Court of Alabama on coram nobis proceedings

and were there found legally insufficient to warrant

relief; and

B. This Court, on certiorari, found that the proceed

ings in the Alabama Supreme Court on petitioner’s

coram nobis application were in compliance with due

process.

III

The Federal District Court and the Circuit Court of Ap

peals erred in refusing to issue a certificate of probable

cause.

Outline of Argument

I

Use by a state of a coerced confession to obtain a convic

tion for a crime is a violation of the due process clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment.

Lee v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 722;

Haley v. Ohio, 332 U. S. 596 ;

MalinsH v. New York, 324 U. S. 401;

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143;

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547;

Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 219;

Vernon v. Alabama, 313 U. S. 547;

White v. Texas, 310 U. S. 530;

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227;

Brown v. Mississippi, 313 U. S. 547.

7

A habeas corpus proceeding in the Federal District

Court is the proper method of attacking a conviction ob

tained in a state court in violation of defendant’s constitu

tional rights, after the exhaustion of state remedies.

White v. Ragen, 324 U. S. 760;

Wade v. Mayo, 332 U. S. 672.

House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 42;

Ex parte Hawk, 321 U. S. 114;

Mooney v. Holokan, 294 U. S. 103;

Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2241-2255.

III

The allegations of a petition for habeas corpus in Fed

eral courts must be taken as true in the absence of an an

swer or a hearing.

White v. Ragen, 324 U. S. 760;

House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 42;

Williams v. Kaiser, 323 U. S. 471;

17. 8. v. Adams, 320 U. S. 220.

IV

The Federal District Court is under the duty to forth

with award the writ of habeas corpus, unless it appears

from the petition itself that the party is not entitled thereto.

Holiday v. Johnston, 313 U. S. 342;

Price v. Johnston, 334 U. S. 266;

Von Moltke v. Gillies, 332 U. S. 708;

Marino v. Ragen, 332 U. S. 561;

U. S. v. Adams, 320 U. S. 220;

Ex parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1;

Walker v. Johnston, 312 U. S. 275;

Title 28, United States Code, section 2243 (then, 28

U. S. C. #461).

I I

8

Y

The prior proceedings in this case did not relieve the Dis

trict Court of its duty to afford petitioner a hearing on

the allegations of the petition for habeas corpus.

House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 42;

Waley v. Johnston, 316 U. S. 101.

VI

This Court has jurisdiction to review by certiorari the

action of the lower Federal courts in declining leave to

appeal in this case and such review estends to questions on

the merits sought to be raised by the appeal.

Title 28, United States Code, section 1651 ( a ) ;

House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 42;

Re 6 2 0 Church St. Building Corp., 299 U. S. 24;

Steffler v. U. S., 319 U. S. 38;

Wells v. U. S., 318 U. S. 257;

Holiday v. Johnston, 313 U. S. 342.

Argument

I

USE BY A STATE OP A COERCED CONFESSION TO OBTAIN A CONVIC

TION FOB, A CRIME IS A VIOLATION OF TH E DUE PROCESS CLAUSE

OF TH E FOURTEENTH AM ENDM ENT.

A conviction based in whole or in part upon a confession

obtained through fear, intimidation or duress deprives a

defendant of due process of law guaranteed by the United

States Constitution.1 This principle has been reiterated by

1 L ee v. M ississippi, 332 II. 8. 772; H a ley v. Ohio, 332 U. S. 596;

M alinski v. N ew Y o rk , 324 U. S. 401; Cham bers v. F lorid a , 309 U. S. 227.

9

this Court in a long line of cases,2 and is applicable both to

convictions in state 3 and Federal courts,4 whether the co

ercion was physical or mental.5

The petition for writ of habeas corpus herein set out

in detail the facts and circumstances surrounding the ob

taining of an involuntary confession from petitioner which

was subsequently used as the basis of his conviction (E.

1-5). These facts, if true, set out a violation of the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution.6

II

A HABEAS CORPUS PROCEEDING IN T H E FEDERAL DISTRICT COUBT

IS THE PROPER M ETH OD OP A TTACKIN G A CONVICTION OBTAINED

IN A STATE COURT IN VIOLATION OP D E PE N D A N T’ S CONSTITU

TIONAL RIGH TS, AFTER TH E EXH AU STION OP STATE REMEDIES

Since Frank v. Mangum, 237 U. S. 309, this Court has

recognized that habeas corpus in the federal courts is

necessary “ to safeguard the liberty of all persons within

the jurisdiction of the United States against infringement

through any violation of the Constitution,” even though

the events alleged to infringe do not appear upon the face of

the record of conviction.7

Power to issue writs of habeas corpus have been con

2 Lee v. M ississipp i, s u p ra ; H a ley v. Ohio, s u p ra ; M alinski v. N ew Y o rk ,

su pra ; A sh cra ft v. T en n essee, 322 U. S. 143; W a rd v. T exa s , 316 U. S.

547; Lisenba v. C aliforn ia , 314 U. S. 219; V ern on v. A labam a, 313 U. S.

547; W h ite v. T exa s , 310 U. S. 530; B row n v. M ississipp i, 313 U. S. 547.

3 See footnote 2, supra.

4 A nderson v. U n ited S ta tes , 318 U. S. 350; M cN abb v. U nited S ta tes ,

318 U. S. 332.

5 A nd erson v. U nited S ta tes , 318 U. S. 350; M cN abb v. U nited S ta tes ,

su pra ; W a rd v. T exa s , supra .

6 Chambers v. F lorid a , supra.

7 M oon ey v. H oloh an , 294 U. S. 103.

10

ferred upon the federal courts by statute,8 and includes the

authority to issue the writ where petitioner is detained by

state authority in violation of his constitutional rights.

This Court has limited this authority by holding that resort

to federal courts for the writ, except in extraordinary cir

cumstances,9 may be had only if all state remedies have

been exhausted.10 Where such state remedies have been

pursued to no avail, however, the defendant may petition

the federal court for habeas corpus relief, where he makes

a substantial showing of violation of his constitutional

rights by a state court.11

In the instant case, petitioner previously applied to the

Supreme Court of Alabama for leave to file a petition for

writ of coram nobis in the state trial court, setting up in

his application specific details surrounding the making of

an alleged confession which was used by the state to obtain

his conviction in the trial court. The Alabama Supreme

Court denied the permission sought and upon certiorari

this Court found that the action of the Alabama Supreme

Court was not in violation of the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Petitioner, thus had exhausted

to no avail the only state remedy provided by Alabama

procedure and accordingly presented his petition for

habeas corpus in the District Court of the United States

for the Middle District of Alabama.

8 Title 28 United States Code, sections 2241-2265.

9 M oore v. D em p sey , 261 U. S. 86.

10 W h ite v. H agen, 324 U. S. 760; H ou se v. M a yo, 324 U. S. 42; E x parte

H aw k, 321 U. S. 114; M oon ey v. H olohan , supra.

11 W ade v. M a yo, 332 U. S. 672.

11

III

THE ALLEGATIONS OF A PETITION FOR HABEAS CORPUS IN FEDERAL

COURTS M UST BE TA K E N AS TRUE IN T H E ABSENCE OF A N A N

SWER OR A H EARING

111 the instant case, the Federal District Court dismissed

the petition for habeas corpus without requiring an answer

and without a hearing. Upon the issuance of its rule to

show cause, the Attorney General of the State of Alabama,

acting for the respondent filed a pleading characterized by

the district court as a “ motion to dismiss” the petition (R.

12). In view of this, therefore, as stated by this Court in

the case of House v. Mayo: “ Since the petition for habeas

corpus was denied without requiring respondent to answer

and without a hearing, we must assume that the petitioner’s

allegations are true. ’ ’ 12

IV

THE FEDERAL DISTRICT COURT IS UNDER TH E DU TY TO F O R TH W IT H

AWARD TH E W RIT OF HABEAS CORPUS, UNLESS IT APPEARS FROM

THE PETITION ITSELF T H A T T H E PA RTY IS NOT ENTITLED

THERETO

The act of the District Judge in issuing an order to show

cause to the Attorney General of the State of Alabama and

in thereafter dismissing the petition without an answer

or a hearing thereon constituted reversible error.