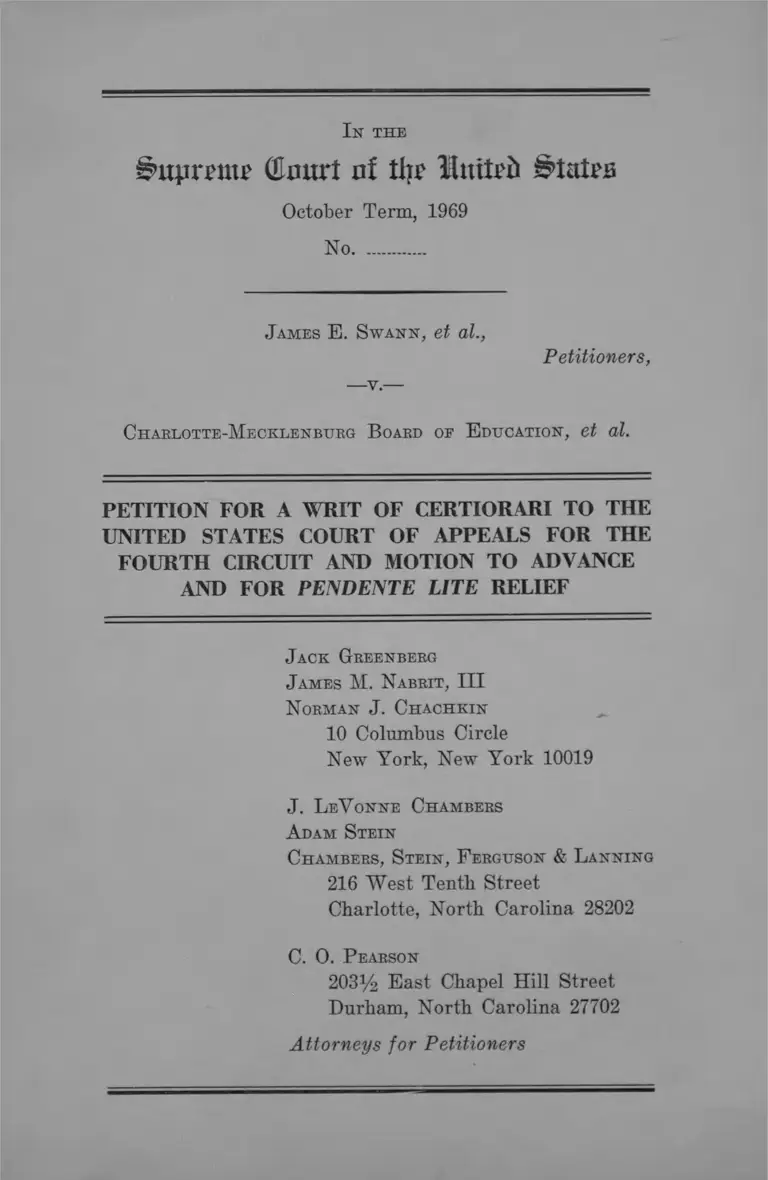

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari and Motion to Advance and for Pendente Lite Relief

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari and Motion to Advance and for Pendente Lite Relief, 1969. 4c888d72-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9bc7e07e-f5e0-4e45-b486-477ac0f44709/swann-v-charlotte-mecklenberg-board-of-education-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-and-motion-to-advance-and-for-pendente-lite-relief. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

CEourt of tljp llmtpfi

October Term, 1969

No..............

J am es E . S w a n n , et al.,

Petitioners,

C harlotte-M ecklenburg B oard of E ducation , et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FOURTH CIRCUIT AND MOTION TO ADVANCE

AND FOR PENDENTE LITE RELIEF

J ack G reenberg

J ames M . N abrit , III

N orm an J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J. L eV onne C ham bers

A dam S tein

C h am bers , S te in , F erguson & L an n in g

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

C. 0. P earson

203V2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below ..................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................. 3

Questions Presented ................... 3

Constitutional Provisions Involved................................... 4

Statement .............................................................................. 4

1. Introduction ............................................................. 4

2. Proceedings Below ................................................. 5

3. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg County School Sys

tem in 1968-69 ......................................................... 9

4. The Schools T oday ................. 14

5. The Plan Ordered by the District C ourt______ 16

Reasons for Granting the W rit:

Introduction ................................................................... 24

I. This Court School Desegregation Decisions

Support the District Court’s Holding That the

All-Black and Predominantly Black Schools in

Charlotte Are Illegally Segregated and Should

Be Reorganized so That no Predominantly

Black Schools Remain. The Court of Appeals

Erred in Substituting a Less Specific Desegre

gation Goal .......................................................... 27

A. The Remedial Goals Set by the Courts

B elow ................................................................ 27

IV

PAGE

Northcross v. Board of Education, 397 U.S. 232

Phillips v. Wearn, 226 N.C. 290, 37 S.E.2d 895 (1946) 32

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968) ....... 6

Rogers v. Hill, 289 U.S. 582 (1933) ............................... 44

Scott v. Spanjer Bros., Inc., 298 F.2d 928 (2nd Cir.

1962) ................................................................................... 42

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ........................... 32

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

243 F. Supp. 667 (W.D. N.C. 1965), affirmed, 369

F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966) ................................................... 1

United States v. Corrick, 298 U.S. 435 (1936) ............... 44

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969) ....................... 36

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

District, 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969) ........................... 36

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) ............................................... 46

United States v. W. T. Grant, 345 U.S. 629 (1953) ....... 44

Vernon v. R. J. Reynolds Realty Co., 226 N.C. 58, 36

S.E.2d 710 (1946) ........................................................... 32

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 47 ....................................................................... 4

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ............................................................ 3

28 U.S.C. § 1343 .................................................................. 5

42 U.S.C. § 1983 .................................................................. 5

V

Other Authorities:

McCormick, Some Observation Upon the Opinion Eule

and Expert Testimony, 23 Texas L. Rev. 109 (1945) 42

“ On the Matter of Busing: A Staff Memorandum from

the Center for Urban Education” , February 1970 .... 52

1969 Report of the Governor’s Study Commission on

the Public School System of North Carolina ........ . 23

Rule 28, Fed. R. Crim. P., 18 U.S.C................................. 42

Statement of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights Concerning the “ Statement by the President

on Elementary and Secondary School Desegrega

tion” , April 12, 1970 .......... ........................ ... ............. 39, 53

2 Wigmore, Evidence, § 563 .............................................. 42

9 Wigmore, Evidence, § 2484 .......................................... 42

PAGE

In the

Sotprntte QInurt of % Itutefc Butts

October Term, 1969

No. ...........

J ames E . S w a n n , et al.,

Petitioners,

C haelotte-M ecklenburg B oakd oe E ducation , et al.

MOTION TO ADVANCE AND FOR

PENDENTE LITE RELIEF

Petitioners respectfully move that the Court advance its

consideration and disposition of this case. It presents

issues of national importance which require prompt reso

lution by this Court for the reasons stated in the annexed

petition for a writ of certiorari. It would be desirable for

the issues to be decided before the beginning of the next

school term in September 1970 in order to guide the many

courts and school boards now making plans for the coming

year and to reduce somewhat the possible necessity for

reorganizations of systems after the 1970-71 school term

is underway.

Wherefore, petitioners pray that the Court:

1. Advance consideration of the petition for writ of

certiorari and any cross-petition1 or other response thereto

1 On June 8, 1970, the Charlotte-Meeklenburg Board of Educa

tion voted in a public meeting to file a petition for certiorari

seeking review of the decision below. We believe the board also

desires expeditious consideration of its views.

2

during the current term, or if need be during the Court’s

vacation or such special or extended term as may be con

venient ;

2. I f the Court determines to grant the petition for

certiorari, arrange such procedures as will permit prompt

decision on the merits as the Court may deem appropriate,

including either summary disposition without argument2

or a special term for argument.3 I f the Court decides to

hear argument, it is suggested that the Court consider the

case on the original record without printing or alternatively

to permit reproduction of the appendix record used in

the court of appeals by other than standard typographic

means.

Petitioners also seek pendente lite relief pending dis

position of the petition for certiorari comparable to that

granted by the Court in Carter v. West Feliciana Parish

School Board, 396 U.S. 226 (1969), and companion cases,

namely, an order providing in substance that:

(1) The respondents shall take such preliminary steps

as may be necessary to prepare for the complete and timely

implementation of the district court’s order of February 5,

1970, as amended by the district court, in the event this

Court should uphold the district court order on the merits;

and

2 Comparable issues have been decided without the necessity for

argument in such cases as Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103

(1965) • Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965); Doivell v. Board of

Education, 396 U.S. 269 (1969); Carter v. West Feliciana Parish

School Board, 396 U.S. 290 (1970) ; Northcross v. Board of Educa

tion, 397 U.S. 232 (1970).

3111 1957 the Court extended its term to hear arguments during

July. Wilson v. Girard, 354 U.S. 524 (1957). Special terms were

convened to consider Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958); Rosen-

317°v'sUlit(19i2)ieS> 346 U'S' 273 ' 1933) ’ and Ex P<irtC Quirin’

3

(2) The respondents shall take no steps which are in

consistent with or will tend to prejudice or delay full im

plementation of the February 5 order as amended at the

beginning of the next school term.

Such an order is obviously necessary to avoid the possi

bility that the passage of time while the case is being

reviewed here will unnecessarily prejudice the substantive

rights of petitioners to attend a unitary system “ at once” .

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S.

19 (1969).

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

N orm an J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J . L eV onne C ham bers

A dam S tein

C h am bers , S te in , F erguson & L a n n in g

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

C. 0. P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

Attorneys for Petitioners

1st the

Supreme (Emtri nf % Imtefc £>tatpa

October Term, 1969

No..............

J ames E . S w a n n , et al.,

Petitioners,

C harlotte-M ecklenburg B oard of E ducation , et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit, entered in the above entitled case on

May 26, 1970.

Opinions Below

The opinions of the courts below directly preceding this

petition1 are as follows:

1. Opinion and order of April 23, 1969, reported at 300

F. Supp. 1358 (Appendix hereto la ).2

1 Earlier proceedings in the same case are reported as Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 243 F. Supp. 667

(W.D.N.C. 1965), affirmed 369 F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966).

2 The appendix of opinions below is printed in a separate volume

because it is voluminous.

2

2. Order dated June 3, 1969, unreported (40a).

3. Order adding parties, June 3, 1969, unreported

(44a).

4. Opinion order of June 20, 1969, reported at 300 F.

Supp. 1381 (46a).

5. Supplemental Findings of Fact, June 24, 1969, 300

F. Supp. 1386 (57a).

6. Order dated August 15, 1969, reported at 306 F .

Supp. 1291 (58a).

7. Order dated August 29, 1969, unreported (72a).

8. Order dated October 10, 1969, unreported (75a).

9. Order dated November 7, 1969, reported at 306 F.

Supp. 1299 (80a).

10. Memorandum Opinion dated November 7, 1969, re

ported at 306 F. Supp. 1301 (82a).

11. Opinion and Order dated December 1, 1969, reported

at 306 F. Supp. 1306 (93a).

12. Order dated December 2, 1969, unreported (112a).

13. Order dated February 5, 1970, unreported (113a).

14. Amendment, Correction, or Clarification of Order

of February 5, 1970, dated March 3, 1970, unreported

(134a).

15. Court of Appeals Order Granting Stay, dated March

5, 1970, unreported (135a).

16. Supplementary Findings of Fact dated March 21,

1970, unreported (136a).

17. Supplemental Memorandum dated March 21, 1970,

unreported (159a).

18. Order dated March 25, 1970, unreported (177a).

3

19. Further Findings of Fact on Matters raised by

Motions of Defendants dated April 3, 1970, unre

ported (181a).

20. The opinions of the Court of Appeals filed May 26,

1970, not yet reported, are as follows:

a. Opinion for the Court by Judge Butzner (184a).

b. Opinion of Judge Sobeloff (joined by Judge

Winter) concurring in part and dissenting in

part (201a).

c. Opinion of Judge Bryan dissenting in part

(215a).

d. Opinion of Judge Winter (joined by Judge

Sobeloff) concurring in part and dissenting in

part (217a).

21. The judgment of the Court of Appeals appears at

226a.

22. The opinion of a three-judge district court in an

ancillary proceeding in this case dated April 29,

1970, not yet reported, appears at 227a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

May 26, 1970 (226a). The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. Section 1254 (1).

Questions Presented

1. Whether the trial judge correctly decided he was

required to formulate a remedy that would actually in

tegrate each of the all-black schools in the northwest

quadrant of Charlotte immediately, where he found that

4

government authorities had created black schools in black

neighborhoods by promoting school segregation and hous

ing segregation.

2. Whether, where a district court has made meticulous

findings that a desegregation plan is practical, feasible and

comparatively convenient, which are not found to be clearly

erroneous, and the plan will concededly establish a unitary

system, and no other acceptable plan has been formulated

despite lengthy litigation, the Court of Appeals has discre

tion to set aside the plan on the general ground that it

imposes an unreasonable burden on the school board.

Constitutional Provisions Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

Statement

1. Introduction

Petitioners are here seeking review of an en banc3 deci

sion of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit setting aside certain portions of an order of District

Judge James B. McMillan of the Western District of North

Carolina which had required the complete desegregation

of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg County public school system.

Three members of the court, in a plurality opinion written

by Judge Butzner, agreed with the lower court that the

school board had an affirmative duty to employ a variety

3 One judge did not participate. Prior to argument, Judge

Craven entered an order disqualifying himself. He had sat and

decided the case as a district judge when it first came to trial in

1965 (243 F. Supp. 667) and was of the opinion that this previous

participation barred him from hearing the case as a circuit judge.

28 U.S.C. § 47.

0

of available methods, including busing, to disestablish its

dual school system, but thought that the extent of busing

required by the district court to desegregate the elementary

schools was unreasonable (184a). Judges Sobeloff and

Winter viewed Judge McMillan’s decision as appropriate

and would have affirmed (201a, 217a). Judge Bryan who

would have reversed the entire order expressed disapproval

of busing to achieve racial balance which he found the

order to require for junior and senior high school students

as well as elementary.

2. Proceedings Below

Black parents and students brought this action in 1965

to desegregate the consolidated school district of Charlotte

City and Mecklenburg County, North Carolina pursuant

to 28 U.S.C. § 1343 and 42 U.S.C. §1983. The North

Carolina Teachers Association, a black professional or

ganization intervened seeking desegregation on behalf of

the black teachers in the school system. This current phase4 * *

4 The case was first tried in the summer of 1965. (243 F. Supp.

667 (1965)) The plaintiffs challenged an assignment plan where

initial assignments were made pursuant to geographic zones from

which students could transfer to schools of their choice. Plaintiffs

complained that many of the zones were gerrymandered and that

the zones of ten rural and concededly inferior black schools which

the board claimed would be abandoned within a year or two over

lapped white school zones. They also attacked the free transfer

policy which had resulted in the transfer of every white child ini

tially assigned to black schools as had the previous minority to

majority transfer policy. Underlying plaintiffs’ specific grievances

was their general assertion that the Constitution required the

school board to take active, affirmative steps to integrate the schools.

Also under attack was the board’s policy looking to the “ eventual”

non-racial employment and assignment of teachers.

The district court approved the assignment plan but required

“ immediate” non-racial faculty practices.

The court of appeals affirmed. (369 F.2d 29 (1966)) The deci

sion noted that the 10 black schools had in fact been closed. The

court held, as it did the following year in Bowman v. The School

Board of Charles City County, 382 F.2d 326 (1967), rav’d sub nom.

Oreen v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391 TJ.S. 430

(1968), that the school board had no affirmative duty to disestab

lish the dual system.

6

of the litigation began in 1968 when the plaintiffs, relying

upon the Green trilogy,6 again sought the desegregation

of the schools.

District Judge James B. McMillan first heard testimony

in March, 1969 and entered his initial opinion the following

month (300 F. Supp. 1358; la ) judging the school system

to he illegally segregated and requiring the board to submit

a plan for desegregation. Extensive proceedings followed

over the next twelve months.6 He rejected the first plan

submitted and called for another, found the second plan

inadequate but accepted it as an interim measure for the

1969-70 school year, again required a new plan which after

review was also found unacceptable.7 On December 1, 1969,

5 Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968); Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450

(1968); and Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968).

6 Judge McMillan has provided an excellent summary of the pro

ceedings in the district court in his Supplemental Memorandum of

March 21, 1970 (159a).

7 The first plan was rejected on June 20, 1969 (46a). The court

found that the board had sought from the staff a “minimal” and in

adequate plan, that the staff produced such a plan and the board

thereupon eliminated its only effective provisions before submitting

it to the court.

The second plan was found inadequate on August 15, 1969 (58a)

but was accepted for the 1969-70 school year only because it prom

ised some measure of desegregation and the court felt there was

not sufficient time prior to the opening of the new school term for

the development and implementation of a more effective plan. The

failure of the board to accomplish what the plan had promised was

determined on November 7, 1969 (82a).

The third plan was not a plan at. all, but simply a statement of

guidelines as to how the board intended to produce a plan. The

guidelines promised no particular results and were thus rejected

on December 1, 1970 (93a).

Judge Sobeloff traces this history in an extensive footnote (213a,

n. 9). He concludes “ [T]he above recital of events demonstrates

beyond doubt that this Board, through a majority of its members,

far from making ‘every reasonable effort’ to fulfill its constitutional

obligation, has resisted and delayed desegregation at every turn.”

7

following the court’s patient but unavailing efforts to secure

from the board an acceptable desegregation plan, the failure

of the board to carry out its minimal interim plan for 1969-

70 which had been “ reluctantly” accepted by the Court in

August of 1969 and the mandate of Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19, that schools are

to be desegregated “ at once” , Judge McMillan decided to

seek assistance from an outside educational consultant to

assist him in devising a unitary system (93a). The follow

ing day the court appointed Dr. John A. Finger, Jr., a

Professor of Education at Rhode Island College who was

directed to work with the administrative staff to prepare a

plan for the court’s consideration (112a). The board was

invited again to submit another plan (93a).

On January 20, 1970, plaintiffs requested that Dr. Finger

bring in his plan so that the schools could be desegregated

“at once” .8 The Finger plan and a fourth board plan were

filed with the court in early February. Judge McMillan

held further hearings and entered an order on February 5

8 Plaintiffs’ request followed the controlling decisions in Alex

ander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969);

Dowell v. Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public Schools,

396 U.S. 269 (1969) ; Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board,

396 U.S. 290 (1970) ; and Neshit v. StatesviUe City Board of Educa

tion, 418 F.2d 1040 (4th Cir. 1969).

This was not the first request by plaintiffs for immediate relief.

In September of 1969 the plaintiffs’ motion for a finding of con

tempt and for immediate desegregation had led to the court’s find

ing in November that the board had not accomplished, during the

1969-70 school year, what it had been ordered to do (80a).

The plaintiffs were required to file a variety of other motions as

well, such as motions for contempt, objections to patently defective

plans, motions enjoining school construction, motions to vacate

state court orders, motions to add new defendants and motions to

enjoin state officials from interfering with orders of the court.

Despite these and other efforts in the district court, the court of

appeals and this Court, the schools are no more desegregated now

than in September 1968 when this round of litigation commenced.

8

directing the desegregation of the students and teachers

of the elementary schools by April 1,1970, and of the junior

and senior high schools by May 4, 1970 (113a).9 The order

was based upon the plan submitted by the board and Dr.

Finger.

The school board appealed and sought a stay in the court

of appeals. On March 5, 1970, the court of appeals stayed

a portion of the order relating to the elementary schools

and directed that the district court make additional find

ings concerning the cost and extent of the busing required

by the February 5 Order (135a). The plaintiffs applied to

this Court to have the partial stay rescinded; the appli

cation was denied.

The district court received additional evidence pursuant

to the directives of the court of appeals and entered a

supplemental Memorandum (159a) and Supplemental Find

ings of Fact (136a) on March 21, 1970.10

9 The order was slightly modified on March 3, 1970 (134a).

10 The supplemental findings were amended in certain respects on

April 3, 1970, in response to a motion by defendants (181a).

During this period there were also proceedings concerning the

North Carolina anti-busing law:

“ In June of 1969, pursuant to the hue and cry which had

been raised about ‘bussing,’ Mecklenburg representatives in the

General Assembly of North Carolina sought and procured pas

sage of the so-called ‘anti-bussing’ statute, N.C.G.S. 115-176.1

[supp. 1969]” (161a).

Plaintiffs were granted leave to file a supplemental complaint in

July, 1969 and to add the State Board of Education and State

Superintendent of Public Instruction as defendants to attack the

statute. At that time the statute did not appear to the court to be

a barrier to school desegregation (see 58a, 64a).

However, in the spring of 1970, the Governor and other state

officials directed that no public funds were to be expended for the

transportation of students pursuant to the district court order of

February 5 and several state judges issued ex parte orders of

similar effect acting under color of the state statute. (See 277a,

229a-230a.) (Continued on p. 9)

9

The opinions and judgment of the court of appeals were

tiled on May 26, 1970. The court decided by a vote of 4 to 2

to vacate and remand the judgment of the district court

for further proceedings. A majority for the judgment was

created by the vote of Judge Bryan joining with the three

members of the court subscribing to the plurality opinion

written by Judge Butzner, although Judge Bryan dissented

from the views expressed in the plurality opinion.11

3. The Charlotte-Meeklenburg County School System

in 1968-69

The plaintiffs presented to the district court detailed

evidence about the school system, such as the number and

location of the schools, the grades served, the kinds of

programs offered, the achievement of the students in the

different schools, the racial distribution of students and

faculties in the system, and the changes which had oc

curred over the years. The plaintiffs also showed by expert

At the plaintiff’s request Judge McMillan added the Governor,

other state officials and one group of state court plaintiffs as defen

dants and determined at that point that the constitutionality of the

state statute was at issue. He therefore requested and the Chief

Circuit Judge appointed a three-judge court. The court convened

in Charlotte on March 24 and on April 29, 1970, the court entered

its decision (227a) declaring unconstitutional the portions of the

statute prohibiting the assignment of any student “on account of

race, creed, color or national origin, or for the purpose of creating

a balance or ratio of race, religion or national origins,” the “ in

voluntary bussing of students in contravention of [the statute]”

and the use of “public funds . . . for any such bussing.” The

court, however, denied plaintiffs’ prayer for injunctions.

11 The judgment was vacated in its entirety. Judge Butzner’s

reason for this action was to give greater flexibility to the develop

ment of a new elementary plan. Judges Winter and Sobeloff thought

it was improper to invite the reconsideration of the portions of

the plan already found acceptable. The judgment expressed Judge

Bryan’s hope that “ upon re-examination the District Court will

find it unnecessary to contravene the principle stated . . .” in his

dissent.

10

testimony the rigid racial segregation of the population in

Charlotte and in Mecklenburg County and its causes.

The court carefully analyzed the voluminous evidence

before it. Over the course of the litigation below, the dis

trict court made extensive findings of fact.12 Each succeed

ing order reflects a comprehensive analysis of new submis

sions of evidence by the parties and the cumulative evidence

already before the court. The court of appeals has ac

cepted the district court’s findings (184a).

Judge McMillan’s first opinion on April 23, 1969, gave

a detailed description of the school system, the community

which it serves and the extent of racial segregation within

the schools (la ). We only summarize here some of the

salient facts contained in the April opinion.

During the 1968-69 school year, students were assigned

to the schools under the same plan as approved by the

district court in 1965—initial assignments by geographic

zones with freedom of transfer restricted only by school

capacities.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system serves more

than 84,000 pupils residing in the city of Charlotte and

Mecklenburg County. In April, 1969, there were 107 schools,

including 76 elementary schools (grades 1-6), 20 junior

high schools (grades 7-9) and 11 senior high schools (grades

10-12). The system employed approximately 4,000 teachers

and nearly 2,000 other employees. The racial composition

of the students in the system was approximately 71% white

12 Signicant findings are contained in eight of the orders leading

to this appeal: Opinion and Order, April 23, 1969 (la ) ; Opinion

and Order, June 20,1969 (46a); Order, June 24,1969 (57a); Order,

August 15, 1969 (58a); Memorandum Opinion, November 7, 1969

(82a); Opinion and Order, December 1, 1969 (93a) ; Order, Febru

ary 5, 1970 (113a) ; Supplemental Findings of Fact, March 21,

1970 (136a); and Further Findings, etc. (181a).

11

and 29% black. The residential patterns of the county were

sufficiently integrated so that most of the county school

zones included both black and white students. No all-black

schools remained in the County. In the City, however, the

residential areas were and are generally segregated by

race,13 and most schools were racially identifiable.

The court found that 14,000 of the 24,000 black students

in the system were attending schools which were at least

99% black. The court further found that most of the de

segregated city schools were in transition from a previously

all-white enrollment to all-black.14 15

The school system had been growing at approximately

3.000 students per year, requiring an on-going school con

struction program. With few exceptions, the size and place

ment of the recently constructed schools produced either

all-white or all-black new schools.16

13 Most of the evidence concerning residential segregation was

produced at the Mareh 1969 hearings. The April order describes

the housing patterns and some of the forces which created them.

The matter was examined again in subsequent orders, particularly

the Order of November 7, 1969 (82a). The court’s conclusion was

that housing segregation in Charlotte has been substantially deter

mined by governmental action.

14 In June, after further analysis of the data, the court concluded

that approximately 21,000 of the 24,000 black students in the system

lived within the city of Charlotte and that nearly 17,000 of them

were attending black or nearly all-black schools. The figure is even

greater if the black students attending schools which are rapidly

becoming all-black are included. 11 schools served 5,502 white

pupils and no black pupils in 1954, served 5,010 pupils of which

35% were black in 1965 and in 1968 served 5,757 students,

81% of whom were black. The court also found that nearly

19.000 of the more than 31,000 white elementary students attended

schools which were nearly all-white. (There are only 150 black

students attending these schools.) More than one-half of the 14,741

white junior high school students attend schools with a total

black population of 193 (50a).

15 The new black schools were generally “walk-in” schools while

the white schools were placed some distance from the areas which

they serve (141a; 142a).

12

The court found faculties segregated. The great ma

jority of the 900 black teachers were teaching in black

schools. There was less than one white teacher per black

elementary school. The two black high schools had teach

ing staffs more than 90% black.

The court concluded that the board’s policies of zoning,

free transfer and its school placement had contributed

to and continued an unlawfully segregated public school

system. It also concluded that the faculties had not been

desegregated as required by the 1965 order. The board

was directed to produce plans for the active desegregation

of the pupils and faculties by May 15, 1969.

On appeal, Judge Butzner agreed that the system was

unlawfully segregated in April of 1969:

“Notwithstanding our 1965 approval of the school

board’s plan, the district court properly held that the

board was operating a dual system of schools in the

light of subsequent decisions of the Supreme C ourt. . . ”

(184a, 185a-186a).16

The district court further found that the impact of

segregation on black students in the system had resulted

in the denial of equal educational opportunities. Compara

tive test results showed a wide disparity in achievement

between students attending all-black schools and students

attending white and integrated schools (58a, 65-a-68a, 93a,

97a-99a, 136a, 144a-145a).

The court also found that the residential segregation

was far from benign or de facto. The school board by gerry

mandering zone lines (53a-54a) and other practices, to

gether with the activities of other governmental agencies,

had a significant impact upon the creation of Charlotte’s

16 Both Judges Sobeloff and Winter concurred in this conclusion

(201a, 217a).

13

ghetto. Again, the three circuit judges subscribing to the

plurality opinion and Judges Sobeloff and Winter con

curred in these findings. As Judge Butzner summarized:

The district judge also found that residential pat

terns leading to segregation in the schools resulted in

part from federal, state, and local governmental action.

These findings are supported by the evidence and we

accept them under familiar principles of appellate re

view. The district judge pointed out that black resi

dences are concentrated in the northwest quadrant of

Charlotte as a result of both public and private action.

North Carolina courts, in common with many courts

elsewhere, enforced racial restrictive covenants on real

property [footnote omitted] until Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U.S. 1 (1948) prohibited this discriminatory prac

tice. Presently the city zoning ordinances differentiate

between black and white residential areas. Zones for

black areas permit dense occupancy, while most white

areas are zoned for restricted land usage.

The district judge also found that urban renewal pro

jects, supported by heavy federal financing and the

active participation of local government, contributed

to the city’s racially segregated housing patterns. The

school board, for its part, located schools in black

residential areas and fixed the size of the schools to

accommodate the needs of immediate neighborhoods.

Predominantly black schools were the inevitable result

(186a).17

17 In addition to the activities of the governmental agencies pro

ducing the discriminatory zoning (13a, 167a) and the urban re

newal program (13a, 167a) mentioned by Judge Butzner, there was

substantial evidence showing that long range planning by the City

Council projects present segregation into the future (167a), that

public housing officials had overtly discriminated until recent years

and has reenforced racial segregation by its site selection (167a)

and that those officials responsible for planning and building streets

and highways have created racial barriers.

14

4. The Schools Today

During the 1969-70 school year the schools were operated

under a desegregation plan submitted to the court in July

1969. The plan provided for the transportation of 4,245

inner-city black students to outlying white schools. Of these

children 3,000 were to come from 7 schools which were being

closed and 1,245 from overcrowded black schools. The plan

proposed some further faculty desegregation but would

retain all other racially discriminatory features of the

school system. The board did propose, however, to study

its building programs and such measures as altering at

tendance lines, pairing, clustering and other techniques in

order to develop a comprehensive desegregation proposal

for the future.

The plaintiffs objected to the plan on the grounds that

it left many schools segregated for yet another year and

placed the full burden of desegregation upon black children.

The court, in an order entered on August 15, 1969 (58a),

approved the proposed pupil reassignments for the 1969-

70 school year “ only (1) with great reluctance, (2) as a

one year temporary arrangement and (3) with the distinct

reservation that ‘one-way bussing’ plans for the years after

1969- 70 will not be acceptable.” The board was ordered

to file a third plan by November 17, 1969, “making full

use of zoning, pairing, grouping, clustering, transportation

and other techniques . . . having in mind as its goal for

1970- 71 the complete desegregation of the entire system to

the maximum extent possible.” 18

Upon application of defendants, the court modified the

August 15 order on August 29 to allow for the reopening

18 The board explicitly refused to follow these directives. Each

of the next two plans submitted by the board rejected the tech

niques of “ pairing, grouping [andf clustering” . See n. 20, infra.

15

of a black inner-city school to serve up to 600 inner-city

children who chose not to be transported to suburban white

schools (72a).

The plan did not accomplish what was expected. The

court later found that “ the ‘performance gap’ is wide”

(84a).

In substance, the plan which was supposed to bring

4,245 children into a desegregated situation had been

handled or allowed to dissipate itself in such a way

that only about one-fourth of the promised transfers

were made; and as of now [March 21, 1970] only 767

black children are actually being transported to

suburban white schools instead of the 4,245 advertised

when the plan was proposed by the board (164a).

In the November, 1969 Memorandum Opinion the court

set out in detail the racial characteristics of the school

system during the 1969-70 school year (82a, 83a-88a). The

court concluded that there had been no real improvement

from the segregated situation found during the previous

school year.

Of the 24,714 Negroes in the schools, something

above 8,500 are attending “ white” or schools not

readily identifiable by race. More than 16,000, how

ever, are obviously still in all-black or predominantly

black schools. The 9,216 in 100% black situations are

considerably more than the number of black students

in Charlotte in 1954 at the time of the first Brown

decision. The black school problem has not been

solved.

The schools are still in major part segregated or

“ dual” rather than desegregated or “unitary.” (86a).

Analyzing the same figures in a later order, the court

pointed out that “ Nine-tenths of the faculties are still

16

obviously ‘black’ or ‘white.’ Over 45,000 of the 59,000 white

students still attend schools which are obviously white.”

(93a, 97a).

The court also determined that the free transfer provi

sion in the board’s plan negated any progress which the

July plan might have produced.19 It also found that

attempts to desegregate the schools by altering attendance

lines would continue to fail as long as students could

exercise a freedom of choice (87a-88a).

The court of appeals shared Judge McMillan’s view that

the system was still segregated during the 1969-70 school

year (188a).

5. The Plan Ordered by the District Court

In the decision of December 1, 1969, in which the court

announced than an educational consultant would be ap

pointed, 19 principles were stated for his guidance (93a,

103a-108a). Dr. Finger’s instructions included: “ all the

black and predominantly black schools in the system are

illegally segregated . . . ” (106a); “ efforts should be made

to reach a 71-29 ratio in the various schools so that there

will be no basis for contending that one school is racially

different from the others, b u t. . . variations from that norm

may be unavoidable” (105a); “bus transportation to elim

inate segregation [and the] results of discrimination may

19 The court had made similar findings in June:

Freedom of transfer increases rather than decreases segrega

tion. The School Superintendent testified that there would be,

net, more than 1,200 additional white students going to pre

dominantly black schools if freedom of transfer were abolished.

(51a-52a)

Moreover, during the choice period prior to the 1969-70 school

year, just two white students out of 59,000 elected to transfer to

black schools and only 330 black students out of 24,000 chose to

transfer to white schools (Id.)

17

validly be employed” (109a); and “pairing, grouping,

clustering, and perhaps other methods may and will be

considered and used if necessary to desegregate the

schools” (107a).

Dr. Finger’s work is described in the Supplemental

Memorandum of March 21, 1970:

Dr. Finger worked with the school board staff mem

bers over a period of two months. He drafted several

different plans. When it became apparent that he

could produce and would produce a plan which would

meet the requirements outlined in the court’s order

of December 1,1969, the school staff members prepared

a school board plan which would be subject to the

limitations the board had described in its November

17, 1969 report.20 The result was the production of

two plans—the board plan and the plan of the con

sultant, Dr. Finger.

The detailed work on both final plans was done by

the school board staff. (169a)

Both plans were presented to the court.21 *

a. High Schools—The school staff had developed a plan

which produced a white majority of at least 64% in each

20 The board’s two most significant limiting factors were: (1)

Rezoning was the only method to be employed; the board rejected

such techniques as pairing, grouping and clustering; (2) a school

sought to be desegregated would be at least 60% white; thus, the

board’s plan for elementary schools produced some schools between

57% and 70% white, eight schools 1% to 17% white, two schools

0% white and no schools between 18% and 58% white (126a-128a).

The court of appeals found as the district court had that these

limiting factors were improper (197a-198a).

21 Description of the plans are found in several of the decisions

below. See, Order, February 5, 1970 (113a, 119a-121a) and tables

(123a-133a) ; Supplemental Findings, March 21, 1970 (136a, 146a-

152a); Supplemental Memorandum, March 21, 1970 (l59a, 169a-

172a); Opinion of Court of Appeals (184a, 190a-191a).

18

of the ten high schools including the presently all-black

West Charlotte (see Exhibit B, 123a). The board accom

plished this result by restructuring attendance lines. Dr.

Finger’s proposal used the board’s new zones and assigned

an additional 300 pupils from a black residential area to

Independence High School which would have had only 23

black students under the board’s plan. Judge McMillan

adopted the Finger modification. This portion of the plan

was approved on appeal. Judge Butzner wrote:

The transportation of 300 high school students from

the black residential area to suburban Independence

School will tend to stabilize the system by eliminating

an almost totally white school in a zone to which other

whites might move with consequent tipping or re

segregation of other schools. (195a)

b. Junior High Schools— During the 1969-70 school year

the board operated 19 junior high schools. Five were all

or predominantly black; eight were more than 90% white.

(See Exhibit D, 124a.) The board, by rezoning eliminated

several of the black schools. One school, however, Pied

mont, remained 90% black. Additionally, four schools

would be more than 90% white.22

Dr. Finger devised a plan which would integrate all the

junior high schools. Twenty of the schools would have

white populations ranging from 67% to 79% and the re

maining school would be 91% white. The plan employed

rezoning and satellite zones.23

22 Two new junior high schools are scheduled to open in the

1970-71 school year. Both proposed plans contemplate assigning

students to these new schools. It is significant that under the board

plan one of the schools would be 100% white and the other 91%

white (124a).

23 A “satellite zone’’ is an area which is not contiguous with the

primary zone.

19

The district court approved of the board’s plan except

as to Piedmont, and gave the board four options: (1) re

zoning to eliminate the racial identity of the remaining

black school, (2) two-way transportation of pupils between

Piedmont and white schools, (3) closing Piedmont, or (4)

adopting the Finger Plan. The board reluctantly chose to

employ the Finger Plan.

Judge Butzner found the plans for junior and senior

high schools by use of satellite zones together with trans

portation “a reasonable way of eliminating all segregation

in these schools” (195a).

c. Elementary Schools—The board in restructuring at

tendance lines for the 76 elementary schools was unable to

affect a majority of the students attending racially identi

fiable schools. As the court of appeals observed, “ Its

proposal left more than half the black elementary pupils

in nine schools that remained 86% to 100% black, and

assigned about half of the white elementary pupils to

schools that are 86% to 100% white.” (191a; see Exhibit

H, 126a-128a.)

The Finger Plan also employed rezoning: 27 schools

were rezoned, and 34 schools were desegregated by group

ing, pairing and transportation between zones.24 Judge

McMillan described the plan:

Like the hoard plan, the Finger plan does as much by

rezoning school attendance lines as can reasonably be

accomplished. However, unlike the hoard plan, it does

not stop there. It goes further and desegregates all

the rest of the elementary schools by the technique of

24 The designated clusters are shown in Exhibit K (132a-133a).

The zones of ten schools remained substantially unchanged.

20

grouping two or three outlying schools with one black

inner city school; by transporting black students from

grades one through four to the outlying white schools;

and by transporting white students from the fifth and

sixth grades from the outlying white schools to the

inner city black school.

The “Finger Plan” itself . . . was prepared by the

school staff . . . . It represents the combined thought

of Dr. Finger and the school administrative staff as

to a valid method for promptly desegregating the ele

mentary schools . . .” . (150a-151a)

Under the plan the elementary schools would be from 60%

to 97% white with most of the schools about 70% white.

(See Exhibit J, 129a-131a.)

Judge McMillan found the board plan to be inadequate

and directed that the Finger Plan or some other plan

which would accomplish similar results be implemented.

The court of appeals agreed that the board plan was un

acceptable. “ The district court properly disapproved the

school board’s elementary school proposal because it left

about one-half of both black and white elementary pupils

in schools that were nearly completely segregated” (197a).

The court of appeals, however, decided that the extent of

transportation required by the Finger Plan was unreason

able and directed further proceedings for the development

of another plan.

d. Transportation—The district court’s order required

additional transportation to be provided. The plurality

opinion approved of the increments of transportation to

accomplish the junior and senior high assignments but

determined that the elementary school busing was excessive.

21

During the 1969-70 school year, the hoard operated 280

school buses transporting 23,600 of its 84,000 students.26

Another 5,000 students rode public transportation at a re

duced fare. The principal’s monthly bus reports show that

between 10,000 and 11,000 of those riding school buses were

elementary students. The average annual cost per child

was about $20.00 or about $472,000.00 out of a total budget

of about 57 million dollars, almost all of which was reim

bursed by the state.26 The buses average 1.8 one-way trips

per day carrying an average of 83.2 students, averaging

40.8 miles (136a, 138a).27

25 Judge McMillan made detailed and elaborate findings concern

ing the extent and cost of busing in the Charlotte system, the state

and the county, in his Supplemental Findings of March 21, 1970

(135a). (See also Further Findings, etc. of April 3, 1970.) The

court had examined the transportation system in previous decisions

as well (la, 22a-23a, 40a, 47a-48a, 113a, 116a-117a).

26 See Further Findings, etc., April 3, 1970 (181a-182a). The

district court had originally understood the average cost to be about

$40.00 per pupil (la, 22a-23a, 136a, 138a). The state reimburses

local school boards for operating expenses for transportation for

those students who are eligible under state law. The original cost

of the bus is borne by the local board but the state replaces worn

out buses (181a-182a).

Pupils eligible for transportation are those children who live

more than 1% miles from school and who live either in the county

or in portions of the city which have been annexed since 1957. Ad

ditionally, the state pays the transportation costs for children who

live within the pre-1957 city limits who attend schools outside of

the pre-1957 limits (136a, 141a).

All but a few hundred of the children to be bused under the court

approved plan would be eligible for transportation at state, rather

than local expense (155a).

27 The overall figures for the state show a higher percentage of

students riding buses than in Charlotte. During the 1968-69 school

year about 55% of all students in North Carolina rode buses to

school; 70.9% were elementary students. (Elementary students are

defined by the state for these purposes as students in grades 1

through 8.)

22

Judge McMillan’s Findings as accepted by the court of

appeals show the added transportation under the plan

ordered on February 5 to be:

No. of

Pupils

No. of

Buses

Operating

Costs

Senior High 1,500 20 $ 30,000

Junior High 2,500 28 50,000

Elementary 9,300 90 186,000

Total 13,300 138 $266,00028

The initial one-time29 capital outlay for the buses would be

$745,200.30

The board itself had proposed the busing of 4,200 black

inner-city children for the 1969-70 school year to outlying

suburban schools as a desegregation measure (58a, 63a-

65a). The board’s February 2 plan proposes to bus approxi

mately 5,000 additional students, about half of whom are

elementary pupils. A major portion of this busing is within

the City (155a, 192a). Moreover, there is nothing novel

28 These are the figures determined by the court of appeals (191a)

by applying the district court’s Further Findings, etc. of April 3,

1970 (181a) to its Supplemental Findings of March 21,1970 (136a).

The board had claimed much greater increases in the extent and

cost of additional busing, but the district court, after carefully

analyzing the data, found the board’s figures to be exaggerated (see

“Discount Factors,” 136a, 152a-154a). The court’s findings are also

consistent with the transportation requirements projected by the

board for its plan to transport 3,000 Negro children to the suburbs

for the 1969-70 year. (See Report filed in summer of 1969, Volume

II, Item 18 of printed Appendix filed in Court of Appeals.)

29 Obsolete buses are replaced by the state. See note 24, supra.

30 The district court observed that there was at least 3 million

dollars worth of vacant school property which had been abandoned

pursuant to the 1969-70 desegregation plan (157a) and which, as the

board had pointed out in its report in the summer of 1969, could be

disposed of to produce necessary “ desegregation” funds. (See Vol

ume II, Item 18 of printed Appendix filed in Court of Appeals.)

23

about city children riding school buses. Children living in

the city but outside of the 1957 city limits are bused.

Many city boards of education, such as Greensboro, provide

transportation for city children with local funds. The

present state superintendent of public instruction, his pre

decessor and the prestigious 1969 Report of the Governor’s

Study Commission on the Public School System of North

Carolina have all recommended that transportation be pro

vided for children, city as well as rural, on an equal basis

(136a-140a).

The bus trips required for the paired elementary schools

would be straight-line non-stop trips (143a), would be

shorter and would take less time than the average bus

trip in the system or in the state (137a).

34. . . .

(f) The average one-way bus trip in the system

today is over 15 miles in length and takes nearly an

hour and a quarter. The average length of the one

way trips required under the court approved plan for

elementary students is less than seven miles, and would

appear to require not over 35 minutes at the most,

because no stops will be necessary between schools

(153a).31

Busing was a technique employed by the board to main

tain its dual system as recently as 1966 (138a); even today,

school buses transport white students to outlying white

schools while Negro students walk to their all-black schools

(141a, 142a).

31 The court later explained how these figures were developed:

The average straight line mileage between the elementary

schools paired or grouped under the “cross-bussing” plan is

approximately 5% miles. The average bus trip mileage of

about seven miles which was found in paragraph 34(f) was

arrived at by the method which J. D. Morgan, the county school

bus superintendent, testified he uses for such estimates—taking

straight line mileage and adding 25%. (Emphasis in original;

153a.)

24

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Introduction

This case merits review on certiorari because it involves

important legal questions about implementing Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), and 349 U.S. 294

(1955), and because it will have important practical con

sequences with respect to school desegregation. In peti

tioners’ view the major questions presented are the related

issues about the proper formulation of specific desegrega

tion goals and the proper standard for appellate review

of a decision on the feasibility of a desegregation plan.

In Part I, infra, we submit that on this record the dis

trict judge was correct in his specific formulation of the

goal of eliminating each predominantly black and all-black

school. We believe the court of appeals erred by substi

tuting a less concrete and complete goal requiring “ all rea

sonable means to integrate the schools” but that not every

school “need be integrated.”

The decision below announces a legal rule of great con

sequence. The court below, by a narrow vote (actually three

members of the court), has explicitly announced a new rule

of law to govern all school desegregation cases. The new

legal principle requires that in each case a court must

decide whether the goal of complete desegregation of all

schools is a reasonable goal. Thus we have not merely an

issue about the reasonableness of methods of desegregation

but rather an issue about the reasonableness of the goal of

desegregation whether the court thinks desegregation is

worthwhile given the circumstances of the district.

As Judge Sobeloff has stated so clearly in dissent, the

new rule portends serious consequences for the general

course of school desegregation:

25

. . . Handed a new litigable issue— the so-called rea

sonableness of a proposed plan— school boards can be

expected to exploit it to the hilt. The concept is highly

susceptible to delaying tactics in the courts. Everyone

can advance a different opinion of what is reasonable.

Thus, rarely would it be possible to make expeditious

disposition of a board’s claim that its segregated sys

tem is not “reasonably” eradicable. Even more per

nicious, the new-born rule furnishes a powerful incen

tive to communities to perpetuate and deepen the

effects of race separation so that, when challenged,

they can protest that belated remedial action would be

unduly burdensome.” (212a-213a)

As thus framed, the issue of appropriate goals for de

segregation plan is one which merits this Court’s expedi

tious attention. The struggle to implement Brown may

founder on the new rule that segregation must be ended

only where it is “reasonable” to end “black” and “white”

schools. This Court’s decision in Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969), may be of

little effect if a kind of reasonableness test on desegregation

timing is replaced by a similar test for deciding the goal.

In Part II, infra, we urge that the court of appeals ap

plied an inappropriate standard for appellate review of

an equitable remedy in setting aside the district court’s

elementary school plan as “unreasonable.” Where no equally

expeditious and effective plan is available, we think it con

trary to this Court’s decisions for an appeals court to

strike down an effective plan which has been reliably found

to be feasible and workable. Moreover, the appellate court’s

view that the remedy was too onerous was influenced by its

erroneous determination that it was unnecessary to inte

grate every school in Charlotte, as discussed in Part I.

26

In addition to these clear legal issues, the case should

also he reviewed because the ultimate decision in this case

will have enormous practical impact on the future of public

school desegregation. The case is singular in a number of

respects. The decision of the district judge on February

5, 1970, which has now been set aside in important part,

immediately assumed national significance and became the

focus of much public attention because it promised the

complete desegregation of every school in an urban school

system. There was this promise of complete desegregation,

notwithstanding the complexity o f a system with 106

schools and more than 84,000 pupils, the recalcitrance of

the locally elected school board, and the concentration of

most Negro residences in one area where a number of all

black schools were maintained. Recent years have seen

considerable school desegregation progress in smaller towns

and rural areas of the South. This is partly because avail

able remedies are more obvious in small school systems.

But most often Negro plaintiffs have been unable to accom

plish anything more than partial desegregation in urban

systems.

Judge McMillan’s decision in the Charlotte case finds a

way to break the pattern and integrate every school in

North Carolina’s largest school district. The Fourth Cir

cuit’s decision reversing the plan for elementary school

desegregation blots out the rays of hope that complete

school desegregation will be accomplished in urban schools.

The result on this appeal clearly signals to every district

judge and school board that a cautious “go-slow” approach

to using busing to eliminate all-black schools is in order.

Judge McMillan’s decisions signaled that substantial de

segregation can be accomplished; the reversal signals that

it will not be accomplished. So the result of the case has

assumed transcending importance. What the Fourth Cir

cuit did speaks as loudly as what it said. What the court

27

did, of course, was overturn one of the first desegregation

orders that ever required complete urban school desegrega

tion in the circuit.

We hasten to add, particularly in view o f our request

for expedition and our suggestion that summary disposi

tion might he appropriate, that the case may well he con

trolled by settled decisions. Although the opinion below

raises the new legal issues we have discussed, they need

not necessarily be decided in the terms in which the court

of appeals posed the issues. Given the findings of the

district judge, which are not clearly erroneous, the deseg

regation plan for Charlotte may be ordered implemented

in September without breaking any new legal ground. The

district court’s decision is supported by a complete record

proving that the existing school system is unconstitutional

and that a feasible remedy is at hand. The meticulous

and painstaking decisions of the district court are ample

support for a decision that the plan should be implemented

as scheduled.

I.

This Court’s School Desegregation Decisions Support

the District Court’s Holding That the All-Black and Pre

dominantly Black Schools in Charlotte Are Illegally

Segregated and Should Be Reorganized So That No

Predominantly Black Schools Remain. The Court of

Appeals Erred in Substituting a Less Specific Desegre

gation Goal.

A. T h e R em edial Goals Set b y the Courts Below .

This case involves whether it was proper, on the record

and findings made, for the district judge to require that

the racially segregated dual system in Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg be thoroughly reorganized so that each of 25 remain-

28

ing all-black or predominantly black schools in the system

will be integrated. Understanding of the issue is aided if

we analyze the particular facts of the Charlotte case as

well as the general legal principles which apply in school

segregation cases.

On December 1, 1969, nearly five years after this suit

was filed by Negro plaintiffs seeking desegregation, Dis

trict Judge McMillan held that:

On the facts in this record and with this background

of de jure segregation extending full fifteen years since

Brown I, this court is of the opinion that all the black

and predominantly black schools in the system are

illegally segregated . . . (106a).

Thereafter, on February 5, 1950, when a concrete plan had

been designed by the court’s expert consultant after work

ing for two months with the local school superintendent

and his staff, it was apparent to Judge McMillan that there

was a feasible way to eliminate the black schools he had

found to be illegal. He thus ordered that “no school be

operated with an all-black or predominantly black student

body” (116a), and the plan was ordered under -which the

percentage of black students would vary in individual

schools from a high of 41% black to a low of 3% black

(156a). Thus the district court first found the black schools

illegal, and then found that their continuation was need

less and that there was an available remedy for the uncon

stitutional situation.

This seemingly straight-forward sequence of events has

been nullified and the mandate of the appeals court now

requires that desegregation planning for Charlotte’s 76

elementary schools begin anew. Petitioners believe that the

court of appeals has not stated the goal of desegregation

planning in suitably specific terms to satisfy the consti-

29

tutional requirement and that the district court’s formula

tion was proper, at least for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

system.

The court of appeals ruling, in the practical context of

the case, requires that some indefinite number of ele

mentary pupils will remain in predominantly black and

perhaps all-black schools. The opinion for three members

of the court, by Judge Butzner, states that “not every

school in a unitary system need he integrated” and that

while boards “ must use all reasonable means to integrate

the schools” sometimes “black residential areas are so large

that not all schools can be integrated by using reasonable

means” (189a). This view acknowledges that the black

schools are the product of illegal segregation practices, but

suggests that the problem is essentially intractable and that

there is in effect a wrong without a remedy. The wrong is

not remedied if you discount as we do, the three alterna

tives to integrating the black schools mentioned by Judge

Butzner, e.g., providing an integrated school for each child

in later years, relying on the black pupils’ use of a free

transfer right to leave the black schools, and establishing

special integrated programs at the all-black schools. None

of these suggestions represents a complete substitute for

the constitutional right to attend school in a system where

racial identification of the schools has been removed and

there are “ just schools.” Green v. County School Board of

New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 442 (1958). The first

method merely postpones the right and does not grant it

“ now and hereafter” (Alexander v. Holmes County Board

of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969)). The second method—

free transfers for blacks—has proven illusory and only a

partial answer in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. Green, supra, and

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1958).

The third method by its own terms is limited to periph

eral activities not central to the daily classroom experience

30

of grade school children, and fails to remove the racial

identifiability of the schools.

We believe that Judge McMillan was correct, and that

the court below was in error, in defining an appropriate

specific desegregation goal for Charlotte. Judge McMillan’s

findings and conclusions that the all black schools and

predominantly black schools in Charlotte-Mecklenburg are

unconstitutionally segregated were accepted by all mem

bers of the court below except Judge Bryan, who wrote a

separate dissenting opinion. Fortunately, this case contains

an unusually detailed and extensive factual record, and

meticulous findings which explain how racial segregation

was created in the Charlotte system. The detailed record

showing how the dual system was created makes the case

an appropriate one to consider the important questions

relating to remedial measures. We set out in detail in the

next subsection the findings about the causes o f school seg

regation, the related findings about the governmental re

sponsibility for housing segregation in Charlotte, and the

particular findings about the effects of the denial of equal

educational opportunity on black children in this locality.

In a succeeding subsection we discuss the governing legal

principles which support Judge McMillan’s statement of

the desegregation goal.

B. T h e D im en sion s, Causes, and Results o f the Dual S ystem

in Charlotte— T h e Nature o f the Constitutional V iolation.

Judge McMillan found that governmental authorities had

created black schools in black neighborhoods in Charlotte

by promoting school segregation and housing segregation.

The board “gerrymandered” or manipulated school atten

dance areas to promote segregation, selected sites and the

sizes of schools to promote segregation, and used the school

transportation system to promote segregation. The court

31

found that the extensive residential segregation which con

centrated 95% of the city’s Negroes in Northwest Charlotte

was promoted by public authorities, including school prac

tices and those of other government agencies.

Judge McMillan summarized the results by noting that

although the slightly more than 24,000 Negroes in the sys

tem were but 29% of the total school population, more than

16,000 Negroes were in 25 all-black or predominantly black

schools, including more than 9,000 in 11 100% black schools

(165a). He concluded that: “The 9,216 in 100% black situ

ations are considerably more than the number of black

students in Chax-lotte in 1954 at the time of the first Brown

decision. The black school problem has not been solved”

(166a). At the same time, more than two-thirds of the

white pupils (45,012 out of a total of 59,828) were in 57

schools readily identifiable as white schools (165a). Less

than one-fifth of the pupils in the system attended 24

schools not readily identifiable by race (165a-166a).

Judge McMillan summarized the findings about how this

extensive segregation came about in these words:

The black schools are for the most part in black resi

dential areas. However, that does not make their

segregation constitutionally benign. In previous opin

ions the facts repecting their locations, their controlled

size and their population have already been found.

Briefly summarized, these facts are that the present

location of white schools in white areas and of black

schools in black areas is the result of a varied group

of elements of public and private action, all deriving

their basic strength originally from public law or state

or local governmental action. These elements include

among others the legal separation of the races in

schools, school busses, public accommodations and

housing; racial restrictions in deeds to land; zoning

32

ordinances; city planning; urban renewal; location of

public low rent housing; and the actions o f the present

School Board and others, before and since 1954, in

locating and controlling the capacity of schools so

that there would usually be black schools handy to

black neighborhoods and white schools for white neigh

borhoods. There is so much state action embedded in

and shaping these events that the resulting segregation

is not innocent or ‘de facto’ and the resulting schools

are not ‘unitary’ or desegregated (166a-167a).

The Fourth Circuit accepted these conclusions (186a-

187a), and also pointed out as one aspect of this, that North

Carolina Courts had enforced racial restrictive covenants

on property prior to Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1. See

e.g. Phillips v. Wearn, 226 N.C. 290, 37 S. E. 2d 895 (1946)

(involving property in Mecklenburg); Eason v. Buff aloe,

198 N.C. 520, 142 S.E. 496 (1930); Vernon v. R. J. Reynolds

Realty Co., 226 N.C. 58 36 S. E. 2d 710 (1946). These racial

restrictive covenants enforced by injunctions and damage

suits were the functional and practical equivalent of res

idential segregation laws and ordinances.32

Nor was the decision below unique in recognizing the inter

relationship between school segregation and state respon

sibility for residential segregation. See Holland v. Board

of Public Instruction of Palm. Beach County, 258 F. 2d 730,

732 (5th Cir. 1958); Dowell v. Board of Education, 244 F.

32 Shelley was argued in this Court on this basis (by the Solicitor

General among others) as Mr. Justice Black has described:

This type of agreement constituted a restraint on alienation

of property, sometimes in perpetuity, which, if valid, was in

reality the equivalent of and had the effect of state and munic

ipal zoning laws accomplishing the same kind of racial dis

crimination as if the State had passed a statute instead of

leaving this objective to be accomplished by a system of private

contracts. (Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226, 329 (1964), Mr.

Justice Black, dissenting.)

33

Supp. 971, 975-977 (W.D. Okla. 1965), affirmed 375 F. 2d

158 (10th Cir. 1967), cert, denied 387 U.S. 931 (1967), both

involving residential segregation ordinances. Cf. Brewer v.

School Board of the City of Norfolk, 397 F. 2d 37, 41-42

(4th Cir. 1968).

Judge McMillan also made explicit findings based upon

his examination of the local system about the harm that

segregation was inflicting upon black children. Judge Mc

Millan found “that segregation in Mecklenburg County

has produced its inevitable results in the retarded educa

tional achievement and capacity of segregated school chil

dren.” (66a-67a). Sixth grade students in black schools

were on the average achieving at a fourth grade level,

whereas there were substantially higher levels in integrated

and white schools. (20a; 67a; 97a-99a). The District Judge

wrote that:

“ This alarming contrast in performance is obviously

not known to school patrons generally.

It was not fully known to the court before he studied

the evidence in the case.

It can not be explained solely in terms of cultural,

racial or family background without honestly facing

the impact of segregation.

The degree to which this contrast pervades all levels

of academic activity and accomplishment in segregated

schools is relentlessly demonstrated.

Segregation produces inferior education, and it

makes little difference whether the school is hot and

decrepit or modern and air-conditioned.

It is painfully apparent that “quality education” can

not live in a segregated school; segregation itself is

the greatest harrier to quality education.

As hopeful relief against this grim picture is the un

contradicted testimony of the three or four experts

who testified, some for each side, and the very interest-

34

ing experience of the administrators of the schools of

Buffalo, New York. The experts and administrators

all agreed that transferring underprivileged black chil

dren from black schools into schools with 70% or more

white students produced a dramatic improvement in

the rate of progress and an increase in the absolute

performance of the less advanced students, without

material detriment to the whites. There was no con

trary evidence. (In this system 71% of the students

are white and 29% are black.) (67a-68a)

Legally, of course, the case does not depend on any such

local findings of harm. “ The right of a student not to be

segregated on racial grounds in schools so maintained is

indeed so fundamental and pervasive that it is embraced in

the concept of due process of law.” Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1, 19 (1958). But it is well to remember that the

segregation system condemned by Brown is a massive in

tentional disadvantaging of the Negro minority by the

white majority. See Black, “ The Lawfulness of the Segrega

tion Decisions,” 69 Yale L. J. 421 (1960). That disad

vantage is not dissipated so long as the dual system is in

tact. The district judge perceived that its elimination is

an urgent task.

C. T h e D ecision B elow Conflicts W ith A pplicable D ecisions o f

This Court.

The district court’s decision that each o f the predomi

nantly black and all-black schools in Charlotte-Mecklenburg

must be reorganized on an integrated basis is in conformity

with this Court’s decisions defining the nature of the duty

to desegregate public schools which was first declared six