Cooper v. Aaron Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cooper v. Aaron Brief for Appellants, 1957. 23570bae-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9c17b06a-ea68-4e29-a493-ed2803be440e/cooper-v-aaron-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

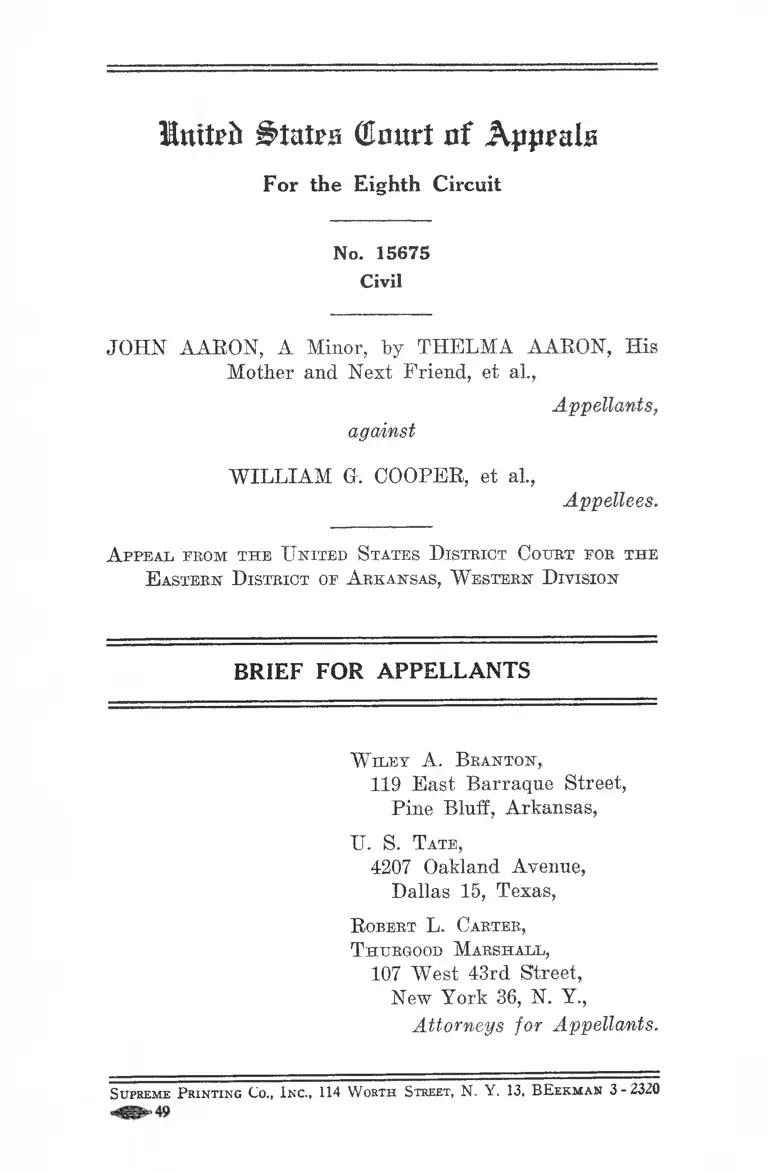

Intteft Stairs OInurt of Appeals

For the Eighth Circuit

No. 15675

Civil

JOHN AARON, A Minor, by THELMA AARON, His

Mother and Next Friend, et al.,

against

Appellants,

WILLIAM G-. COOPER, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the U nited States District Court for the

E astern District of A rkansas, W estern Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

W iley A. Branton,

119 East Barraque Street,

Pine Bluff, Arkansas,

U. S. T ate,

4207 Oakland Avenue,

Dallas 15, Texas,

R obert L. Carter,

T hijrgood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.,

Attorneys for Appellants.

S upreme P rinting Co., I nc., 114 W orth S treet, N. Y. 13, B E ek m an 3-2320

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ............................................. 1

Points and Authorities ........................ ................... 5

Argument:

There Are No Valid Reasons of an Equitable or

Administrative Nature Warranting Appellees

Being Granted an Extension of Time Beyond

September, 1957, Either in Starting or Com

pleting Desegregation at the Junior High and

Elementary School Levels in the Little Rock

School District Such as Proposed by Appel

lees and Approved by the Judgment Below . .. 5

Conclusion................................ ................................. 16

Table of Cases

Booker, et al. v. State of Tennessee Board of Educa

tion, —- F. 2d — (6th Cir. Jan. 14, 1957)............... 15

Bowles v. Simon, 145 F. 2d 334 (7th Cir. 1944)....... 15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; 349 U. S.

294 ....................................................................2,3,5,14,15

Bush v. Orleans School Board, 138 F. Supp. 336, 337

(E. D. La. 1956)...................................................... 2

Clemons v. Board of Education, 228 F. 2d 853 (6th

Cir. 1956) ............................................................... 5,15

Ex parte Poresky, 290 U. S. 3 0 .................................. 2

Orleans School Board v. Bush, 351 U. S. 948 ........... 2

Pierce v. Board of Education of Cabell County (S. D.

W. Va. 1956), unreported .................................... 14

Shedd v. Board of Education of Logan County (S. D.

W. Va. 1956), Civil Action 873, unreported........... 14

ii

PAGE

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631................ 6

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ................................. 6

Thompson v. School Board of Arlington County, 144

F. Supp. 239 (E. D. Ya. 1956), aff’d — F. 2d —

(4th Cir. Dec. 31, 1956) ........................................ 14-15

Union Tool Co. v. Wilson, 259 U. S. 107, 112............. 15

Willis v. Walker, 136 F. Supp, 177 (W. D. Ky. 1955) 5,14

Other Authorities

Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (1954).................. 11

Ashmore, The Negro and the Schools (1954)........... 9,10

Blose and Jaracz, Biennial Survey of Education in

the United States 1948-1950, Table 43 (1952)....... 7

Bustard, The New Jersey Story, 21 Journal of Negro

Education (1952) .................................................... 10

Chein, Deutsch, Hyman and Jahoda, Ed., Consistency

and Inconsistency in Inter group Relations, 5 Jour

nal of Social Issues (1949) .................................... 11

Clark, Desegregation: An Appraisal of the Evidence,

9 Journal of Social Issues (1953) ....................... 9,10

Clark, Effects of Prejudice and Discrimination on

Personality Development (1950) ........................... 10

Dean and Rosen, A Manual of Intergroup Relations

(1955) ......................... 9,10,11

Delano, Grade School Segregation: The Latest

Attach on Racial Discrimination, 61 Yale L. J.

(1952) ...................................................................... 10

Deutsch and Collins, Interracial Housing (1951) . . . 11

Grambs, Education In A Transition Community,

Commission on Educational Organizations, Na

tional Conference of Christians and Jews ............ 9

Ill

PAGE

Kutner, Wilkens and Yarrow, Verbal Attitudes and

Overt Behavior Involving Racial Prejudice, 47

Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology (1952) 11

LaPiere, Attitudes vs. Action, 13 Social Forces

(1934) ..................................................................... 11

Lee, Attitudinal Multivalence in Culture and Per

sonality, 60 American Journal of Sociology (1954-

55) ................................................ 11

Saenger and Gilbert, Customer Reactions to the

Integration of Negro Sales Personnel, 4 Inter

national Journal of Opinion and Attitude Research

(1950) ............................................................ 11

Swanson and Griffin, Public Education in the South

Today and Tomorrow, Table 33 (1955) .................. 7

Thompson, E d.:

Next Steps in Racial Desegregation in Educa

tion, 23 Journal of Negro Education (1954) .. 9,10

The Desegregation Decisions One Year After

ward, 24 Journal of Negro Education (1955) 9,10

Educational Desegregation, 1956, 25 Journal of

Negro Education (1956) ................................. 9,10

Tipton, Community in Crisis (1953)......................... 9

Williams, The Reduction of Intergroup Tensions

(1947) ............................................................ 11

Williams, Jr. and Ryan, Schools in Transition (1954) 9,10

Wilmer, Walkley and Cook, Human Relations in

Interracial Housing (1955) .................................. 11

Inttefc States Olmtrt nf Appeals

For the Eighth Circuit

No. 15675

Civil

J ohn A aron, A Minor, by T helma Aaeon, His Mother

and Next Friend, et al.,

Appellants,

against

W illiam G. Cooper, el al.,

Appellees.

Appeal F rom the U nited States District Court for the

E astern District of Arkansas, W estern Division--------------------- o----------------------

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

Appellants here are children of public school age who

are eligible to attend and are attending the public schools

in Little Rock, Arkansas, and their parents and guardians.

All are Negroes. Suit is brought on behalf of the named

appellants and all other Negroes similarly situated and

affected. Pursuant to law, local policy, custom, usage

and regulation the schools in Little Rock are operated by

appellees on a racially segregated basis.

Appellants have made application to the school board

of appellee School District to cease and desist the unlaw

ful discrimination of assigning these appellants and other

Negro children to schools on the basis of race and color

2

and to permit them and all other Negro children similarly

affected to register, enroll, enter, attend classes and receive

instruction in the public schools under the same terms and

conditions as all other educable children of public school

age and without any distinctions, restrictions or limita

tions based on race or color. The minor appellants have

been tendered to the Central High, Technical High, Forest

Heights Junior High and Forest Park Elementary Schools—

all operated exclusively for white children—which are the

schools closest to appellants’ homes and to which they

would normally be assigned but for their race and color.

Appellees have refused or failed to act favorably upon

appellants ’ requests, and this suit was thereupon instituted.

In their complaint appellants invoke jurisdiction under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281, but the court

refused to convene a three-judge court and heard the cause

sitting alone.1

Appellees in their answer placed no reliance on state

laws requiring segregation in public schools but urged that

they had made a prompt start towards full compliance

with the mandate of the United States Supreme Court in

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, and presented

a plan calling for desegregation at the senior high school

level as soon as the West End High School was ready for

occupancy (now set for September, 1957 (R. 70)), and

after successful completion at this level (estimated at

between 2-3 years (R. 88)), to be followed by desegrega

tion at the junior high school level and after successful

completion at this level (estimated at between 2-3 years

1 Appellants make no issue here of the court’s failure to convene

a three-judge court and concede that the applicable precedents fully

support the jurisdiction of the lower court. That a state policy requir

ing segregation in public schools is unconstitutional is now established

beyond question. Hence, injunctions to restrain enforcement of such

a state policy can be issued by regularly constituted United States

District Courts. See Ex parte Poresky, 290 U. S. 30; Bush v.

Orleans School Board, 138 F. Supp. 336, 337 (E. D. La. 1956);

Orleans School Board v. Bush, 351 U. S. 948.

3

(R. 88, 89)), to be followed by desegregation in the ele

mentary grades. Appellees urged that this plan conformed

to the requirements of the law, and that the complaint be

dismissed (R. 19-29).

A trial on the merits took place on August 15, 1956.

The evidenciary facts there adduced are not in dispute:

The Little Rock School System consists of elementary

schools (grades 1-6), junior high schools (grades 7-9) and

senior high schools (grades 10-12) or what is commonly

called a 6-3-3 system (R. 13). The total student popula

tion is 21,726, distributed as follows: 3,303 Negro and

9,285 white children in elementary schools; 1,252 Negro

and 3,831 white children in junior high school; and 929

Negro and 3,126 white children in senior high schools

(R. 41-44). There are three senior high schools, one of

which is a technical high school which is offering a

specialized course of study now available only to white

children, and another senior high school is presently being

erected (R. 42).

On May 20, 1954, three days after the decision in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, the school

board of the appellee School District adopted a resolution

in which full implementation of the Court’s decision was

promised after an adequate plan and program of com

pliance had been formulated (R. 69). The Superintendent

of Schools was authorized to prepare a plan to carry

out this stated policy. The Superintendent formulated

such a plan, and on May 24, 1955, it was approved and

adopted by the Board. The plan is set out in full in the

court’s opinion (R. 37, et seq.).

The plan sets forth various standards and guides which

the Board considers essential to the successful desegregation

of its school plant. It found that desegregation would

place no serious additional financial burden on appellee

School District; that integration could not be accomplished

until needed school facilities had been completed. These

facilities were specified as three senior high schools and

six junior high schools.

4

Desegregation is to proceed in three stages. The first

step will involve the senior high schools; after successful

desegregation there, the second stage involving the junior

high schools will commence; after successful desegrega

tion there, the third and final phase will be instituted,

involving desegregation of the elementary schools. The

plan indicates that in the Board’s judgment it is best to

commence desegregation at the senior high school level,

because fewer students and teachers are affected and to

proceed in stages, in order to benefit from experience, and

to desegregate elementary schools last, because “ establish

ment of attendance areas at the elementary level is most

difficult due to the large number of both students and

buildings involved.’’ This plan was adopted in May, 1955,

and its first phase is now scheduled to commence beginning

September, 1957—desegregation at the senior high school

level.

Appellees sought to establish that they were acting

in good faith and that their proposed plan had to be fol

lowed in order to enable the school board to accomplish

desegregation without lowering educational standards.

Appellants sought to bring out in cross-examination of

the Superintendent that the problems set forth as justifica

tion for delay in starting and completing desegregation

were common to most public school systems and were not

indigenous to the institution of a non-discriminatory school

program; that desegregation could be accomplished at once

and that no good cause had been shown by appellees to

warrant the court giving its approval to the plan proposed.

The court, nonetheless, concluded that appellees’ pro

posed formula constituted good faith compliance with the

Supreme Court’s decision and ordered appellees to

proceed to desegregate the Little Rock School System

pursuant to the three step program as proposed. There

upon, the complaint was dismissed, and appellants brought

the cause here.

5

POINTS AND AUTHORITIES

There are no valid reasons of an equitable or adminis

trative nature warranting appellees being granted an

extension of time beyond September, 1957, either in start

ing or completing desegregation at the junior high and

elementary school levels in the Little Rock School District

such as proposed by appellees and approved by the judg

ment below.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 349

U. S. 294;

Booker, et al. v. State of Tennessee Board of

Education, — F. 2d — (6th Cir. January 14,

1957);

Willis v. Walker, 138 F. Supp. 177 (W. D. Ky.

1955);

Clemons v. Board of Education, 228 F. 2d 853

(6th Cir. 1956).

ARGUMENT

There Are No Valid Reasons of An Equitable or

Administrative Nature Warranting Appellees Being

Granted An Extension of Time Beyond September,

1957, Either in Starting or Completing Desegregation at

the Junior High and Elementary School Levels in the

Little Rock School District Such As Proposed by Ap

pellees and Approved by the Judgment Below.

1. In the second Brown decision (349 II. S. 294), the

Court set forth principles which were to guide lower courts

in litigation involving implementation of the Court’s man

date outlawing segregation in public schools. Under the

Brown formula, the lower court is empowered to weigh and

balance appellants’ personal interest in immediate admis

sion to public schools on a non-discriminatory basis against

6

the public interest in having the transition from segregation

to non-segregation take place in a systematic and orderly

fashion. These private and public interests are to be

adjusted and reconciled so that equal educational oppor

tunities are afforded to all with the least practicable delay,

and the change-over in the school system is allowed to

take place in an orderly fashion.

At the threshold of the question here presented is

whether the court’s approach to this question was in keep

ing with this formula. We think it was not. Appellants’

right to a public education free of discrimination based upon

race or color is present and immediate. Sipuel v. Board of

Regents, 332 U. S. 631; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629.

This right exists as an effective one only for a short period

of time—here only as long as appellants are eligible to

attend and are attending public school. In the very nature

of things, since various obstacles have to be overcome before

segregation can be eliminated, this right will be forever lost

for some children and seriously impaired as to others. Some

will have graduated before desegregation takes place, and

others will be so far advanced that the one or two years of

schooling left for them, even if under nondiscriminatory

conditions, will not be sufficient for them to overcome the

handicaps of many years of inferior education.

Appellees propose a plan whereby desegregation in the

Little Eock School System is to commence next term at the

senior high iSchool level.2

2 Appellees insist that desegregation cannot commence until the

new senior high school is finished (West End High School). Com

pletion is now scheduled for July, 1957. Appellants have raised

objection to delay until the new school is ready for occupancy. But

West End High School will be ready for occupancy in September,

1957. Since this cause will not be reached for argument before the

commencement of the last semester of the present school term, Sep

tember, 1957, is the earliest practicable date this Court could insist

upon a start being made. Thus appellants’ contentions that desegre

gation in fact could have and should have commenced earlier are now

largely academic.

7

After the successful completion of this phase of the pro

gram, desegregation will start at the junior high school level.

The start of the next phase is dependent upon the success

of the preceding steps, and hence under the Board’s formu

lation there are no definite terminal dates for the beginning

of one phase and the commencement of the next. The Super

intendent estimated that desegregation might start at the

junior high school level 2 or 3 years after it is instituted

at the senior high school level—1959-60,1960-61 (R. 88), and

it might start at the elementary grades 2 or 3 years after it

has been instituted at the junior high school level. Thus, it

is conceivable that desegregation will be completed by the

1963-64 school term. The evidence discloses, howmver, that

this is not definite, nor even a calculated guess, and it is

conceivable that the time estimated by Mr. Blossom may be

extended appreciably.

The court in approving this plan has lost sight of the

great private interest which these appellants have in being

afforded the right to equal education with the least practica

ble delay. That a Negro child attending segregated schools

in Arkansas receives educational advantages inferior to a

white child is clear from statistical data. In 1949-1950 the

State spent $123.60 for the education of every white child

and only $73.03 for every Negro child—a differential of

$50.53.® In 1951-1952, each child got less and the figures

were $102.05 and $67.75 respectively—a differential of

$34.30.4 That this short-changing of Negro children neces

sarily results in lowered educational standards in the schools

for Negroes is beyond dispute. Hence., for the Negro child,

insistence upon immediate vindication of his right to be

admitted to public schools without discrimination based

upon race or color is a matter of vital and pressing con-

3 Blose and Jaracz, Biennial Survey of Education in the United

States 1948-1950, Table 43 (1952).

4 Swanson and Griffin, Public Education in the South Today and

Tomorrow, Table 33 (1955).

8

cern. But the court below approved proposals which will

continue a pattern of inferior schooling for the majority

of Negro children presently enrolled in Little Rock public

schools for several years to come. By 1960-1961 wheii

desegration may commence at the junior high school level,

all Negroes now in junior high school will have graduated

to senior high school and will have opportunity for only

three years of unsegregated education. By 1963-64, when

desegregation may be commenced at the elementary school

level, all Negro children presently enrolled in elementary

schools will have graduated and will have been deprived,

of six years of unsegregated and equal education. This

is a long time to deny vindication of a right so basic and

fundamental as that here being asserted without some

over-powering justification. This is particularly true, in

view of appellees’ own admission that they have the

physical facilities to desegregate all of their schools now

(R. 81, 88).

This admission was made on several occasions during

the trial, but the Superintendent felt, however, that he

could not desegregate now and maintain educational stand

ards at the level he desired. Since Negro children are

presently receiving inferior education, what this sentiment

undoubtedly reflects is a fear that the mixing of Negro

children, handicapped by inferior educational offerings, into

schools with white children might lower the educational

standards maintained at the heretofore all-white schools.

If this is the basic problem, then that is all the more reason

why desegregation at the elementary level should take

place without undue delay, before the inferior educational

offerings available have had too great an impact on the

child’s educational development. Thus, we submit, if the

basic reason for the proposed formula is the fear of lower

ing educational standards, then all the plan proposes to do

is to make .solution of this problem more difficult for all

the Negro children presently enrolled in school. This fear

9

constitutes no reason for continuing to relegate Negro

children to inferior education but places upon the school

board the necessity of giving special attention to these

children, when segregation is removed, so as to help them

overcome the disabilities of inferior education as soon as

possible.

Further, there is nothing other than the unsupported

opinion of the Board as set forth in the plan itself and the

Superintendent’s testimony to validate the plan as a sound

one.

There is no objective evidence that it is easier to achieve

successful desegregation by a step by step process involv

ing successive desegregation of small segments of an insti

tution until the whole job is accomplished. Examination

of the actual instances of desegregation reveals that seg-

mentalized desegregation, including the progressive de

segregation of different grades of each school unit, does

not allay anxieties and doubts, or assure a greater com

munity acceptance of desegregation.5 Contrarily, such

methods appear to mobilize the resistance of those white

persons immediately affected, since they feel themselves

arbitrarily selected as an “ experimental” group. The

remaining individuals in the community then observe con

flict instead of a process of peaceful adjustment. Hence,

5 Ashmore, The Negro and the Schools 79-80 (1954) ; Clark,

“Desegregation: A n Appraisal of the Evidence” 9 Journal of Social

Issues 1-68, especially 45-46 (1953) ; Dean and Rosen, A Manual of

Intergroup Relations 57-108, especially 70 (1955) ; Grambs, Educa

tion In A Transition Community, Commission on Educational Or

ganizations, National Conference of Christians and jews 37, 39-40;

Thompson, Ed. “Next Steps In Racial Desegregation in Education”

23 Journal of Negro Education (1954); Thompson, Ed. “The De

segregation Decision: One Year Afterward” 24 Journal of Negro

Education (1955); Thompson, Ed. “Educational Desegregation,

1956” 25 Journal of Negro Education (1956); Tipton, Community

In Crisis, especially 71 (1953) ; Williams, Jr. and Ryan, Schools In

Transition 241-244 (1954).

10

their own anxieties are increased and resistance stiffens.

This reaction may then become self-perpetuating, resulting

in ineffective and incomplete desegregation.6

In addition to these problems, a major objection to

such a plan is that it can result in some children in the same

family attending non-segregated classes while their brothers

and sisters attend segregated classes. This would stimulate

and intensify problems of intra-family relationships and

aggravate the known psychological reactions to racial

segregation and discrimination.7

Analysis of instances where an extended time period for

desegregation has been utilized indicates that this plan may

be interpreted by the general community, white and Negro,

as indicative of anxiety and hesitancy about ending segre

gation or an intention of evading non-segregation. The

evidence indicates that rather than obtaining community

acceptance of non-segregation, this method may reinforce

initial resistance and opposition to desegregation.8

Adoption of this method is often predicated upon

the erroneous assumption that changes in attitude must

6 See footnote 5, supra.

7 Clark, Effects of Prejudice and Discrimination on Personality

Development (1950). See also footnote 5, supra.

8 Ashmore, The Negro and the Schools 40-84, op. cit. supra,

note 5; Bustard, “The New Jersey Story” 21 Journal of Negro

Education 275-285 (1952); Clark, “Desegregation-. A n Appraisal

of the Evidence” 9 Journal of Social Issues 1-68, op. cit. supra,

note 5; Dean and Rosen, A Manual of Intergroup Relations 57-108

(1955); Delano, “Grade School Segregation: The Latest Attack

on Racial Discrimination” 61 Yale L. J. 738-744 (1952) ; Thomp

son, Ed. “Next Steps in Racial Desegregation in Education 23

Journal of Negro Education 201-338 (1954); Thompson, Ed. “The

Desegregation Decision: One Year Afterward” 24 Journal of Negro

Education 165-381 (1955); Thompson, Ed. “Educational Desegre

gation, 1956” 25 Journal of Negro Education (1956); Williams,

Jr. and Ryan, Schools in Transition, op cit. supra, note 5.

11

precede desegregation. Public opinion and acceptance

are important factors in obtaining effective desegrega

tion, but in many instances they follow rather than

precede the enforcement of non-segregation. Examina

tion of actual changes from public school segrega

tion to non-segregation clearly indicates that resistance

to desegregation is greater in anticipation of the change

to non-segregation than when desegregation actually

occurs.9

It appears, therefore, that the segmentalized approaches

to desegregation tend to result in ineffective desegrega

tion.10

Granted the difficulties of the problem, courts are not

to exercise their equity power merely to give time for the

sake of time, but are to exercise it to afford time for sys

tematic and effective change where such may be necessary

in the public interest. In larger cities than Little Bock

desegregation was accomplished over a much shorter time

span and without apparent adverse effects. This was true

of Louisville, Kentucky; Kansas City, Missouri; St. Louis,

9 Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (1954); Chein, Deutsch,

Hyman and Jahoda, Ed., “Consistency and Inconsistency In Inter-

group Relations” 5 Journal of Social Issues 1-63 (1949); Deutsch

and Collins, Interracial Housing (1951) ; Kutner, Wilkens and

Yarrow, “Verbal Attitudes and Overt Behavior Involving Racial

Prejudice” 47 Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 649-652

(1952); LaPiere, “Attitudes vs. Action” 13 Social Forces 230-237

(1934); Lee, “Attitudinal Multivalence in Culture and Personality”

60 American Journal of Sociology 294-299 (1954-55) ; Saenger and

Gilbert, “Customer Reactions to. the Integration of Negro Sales Per

sonnel” 4 International Journal of Opinion and Attitude Research

57-75 (1950); Williams, The Reduction of Intergroup Tensions

(1947); Wilmer, Walkley and Cook, Pluman Relations in Inter

racial Housing (1955); Dean and Rosen, A Manual of Intergroup

Relations 57-108, op. cit. supra, note 5, and see other citations in

note 5.

10 See note 8, supra.

12

Missouri; Washington, D. C.; Baltimore,, Maryland. Cer

tainly, with a smaller school population, fewer teachers,

buildings and attendance areas, Little Rock should be able

to plan and implement an effective program of transition

on a much more accelerated time schedule than could be

possible in larger urban centers heretofore referred to.

Hence, it is submitted, that in a balancing of the equities

no good cause has been shown which would justify or

warrant the court below in postponing beyond September,

1957, vindication of the present rights of these appellants

to admission to schools without restrictions based upon

race.

2. Presumably appellees, in proposing to commence

desegregation at the senior high school level in September,

1957, are making a “ prompt and reasonable start towards

full compliance” with the May 17, 1954, ruling of the

United States Supreme Court. But the fact that a start

has been made does not render automatic a grant of

additional time to complete the process. Such an exten

sion should be given only where necessary to implement

the May 17, 1954, ruling in an effective manner.

“ The burden rests upon the defendants to

establish that such time is necessary in the public

interest and is consistent with good faith compliance

at the earliest practicable date. To that end, the

courts may consider problems relating to adminis

tration, arising from the physical condition of the

school plant, the school transportation system,

personnel, revision of school districts and attend

ance areas into compact units to achieve a system

of determining admission to the public schools on

a non-racial basis, and revision of local laws and

regulations which may be necessary in solving the

foregoing problem. ’ ’

13

There is nothing in the evidence in this case to show

that any administrative problems exist of the nature set

forth in the Brown decision to warrant delay in implementa

tion of appellants’ unquestioned constitutional rights.

Appellees raise questions concerning the physical

deficiencies of the school plant but according to their own

plan the physical deficiencies which delayed desegregation

have now been remedied. There are six junior high schools,

and there will be three senior high schools ready for

occupancy in September, 1957, when the West End High

School is completed. In addition there is Technical High

School.

In May, 1955, this was the indispensable condition to

accomplishing desegregation. In August, 1956, however,

added reasons were voiced for deferring accomplishing

desegregation until 1963 or beyond. What these problems

are is not clear from Mr. Blossom’s testimony.

Appellees are concerned about the public’s reaction to

desegregation and have sought to obtain public acceptance

of the Board’s plan by having it read and explained to

some 125-150 groups (R. 69). Appellees have problems

of finance, procurement and training of an adequate staff,

development of a sound curriculum, development of attend

ance areas to enable each child to attend school in the

area in which he resides, of seeking to make certain that

each classroom contains teachable groups of youngsters.

Their objective is to provide the best possible education

and to seek to satisfy the education needs of each child

insofar as possible. (See testimony of the Superintendent

of Schools, R. 69, et seq.) While all of these problems

are common to any school system, it is appellees’ conten

tion that the mere elimination of racial separation in a

school system makes them more acute and pressing (R. 88).

It is asserted that whenever desegregation takes place, it

will create problems; postponement, however, gives time

for understanding (R. 88). Appellees’ basic thesis is that

14

racial differences affect school achievement, and, therefore,

desegregation presents problems of curricula planning (R.

89). In this regard it is their contention that desegrega

tion per se creates administrative problems of great

magnitude.

There is no denying the fact that desegregation of the

Little Rock Schools will cause problems, but there is no

evidence that problems of an administrative nature will be

created such as to warrant extended delay in completing

the process as is now approved by the judgment below. Any

change creates some difficulties, and in this instance there

is a great emotional attachment to the present discrimina

tory practices. But compliance with the law cannot be put

off because some members of the public do not want to

change their habits or customs. See Brown v. Board of

Education, supra. Indeed, the objective evidence indicates

that unwarranted delays, not based on administrative needs

in effecting desegregation, may result in confusion, con

flict and race tensions and thereby render public acceptance

more of a problem than it would have been.11

Similar plans have been rejected by courts as not in

accord with the requirements of the law. In Pierce v.

Board of Education of Cabell County (S. D. "YV. Va. 1956),

unreported, the court rejected a proposed plan in which

desegregation would be completed in a period of 12 years

and ordered immediate desegregation. Similarly, in Shedd

v. Board of Education of Logan County (S. D. W. Va.

1956), Civil Action 873, unreported, the Board of Educa

tion proposed to complete desegregation of the first six

grades in September 1956 and to defer desegregation of

grades 7-12 until the completion of two new buildings.

The court rejected this proposal and ordered desegrega

tion completed in all grades by September 1956. In Willis

v. Walker, 136 F. Supp. 177 (W. D. Ky. 1955) and in

Thompson v. School Board of Arlington County, 144 F.

11 See note 5, supra.

15

Supp. 239 (E. D. Va. 1956), aff’d — F. 2d — (4th Cir.

Dec. 31, 1956), plans seeking extended time spans tq

accomplish desegregation were rejected as violative of

plaintiffs’ rights to equal educational opportunities.

Under appellees ’ plan, all of these appellants not now in

senior high school will be denied their present and personal

rights to equal educational opportunities for periods of

3-6 years and perhaps even more. To deny appellants’

rights for this length of time, we submit, constitutes

non-compliance with the declaration of the Supreme Court

in the Brown case. See Clemons v. Board of Education,

228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956); Booker v. State of Tennessee

Board of Education, — F. 2d — (6th Cir. decided Jan. 14,

1957).

There can be no justification for a delay which would

relegate these appellants and the majority of the other

Negroes in the Little Rock schools to inferior education

for an extended period of time, while the school board

wrestles with these problems with which it is now faced

and will have to face for many years after unsegregated

education has become an accepted fact of American life.

There is no dispute as to the evidentiary facts. In

failing or refusing to apply the law to these facts, or in

misapplying the law, the court below has failed in its

obligation to follow and apply the yardstick laid down by

the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, supra.

This, we submit, is reversible error. Union Tool Co. v.

Wilson, 259 U. S. 107, 112; Bowles v. Simon, 145 F. 2d

334 (7th Cir. 1944); Booker v. State of Tennessee Board

of Education, supra-, Clemons v. Board of Education, supra.

16

Conclusion

For the reasons hereinabove indicated, it is respectfully

submitted that the judgment of the court below should be

reversed.

W iley A. Braxton,

119 East Barraque Street,

Pine Bluff, Arkansas,

U. S. T ate,

4207 Oakland Avenue,

Dallas 15, Texas,

R obert L. Carter,

T huegood Marshall,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.,

Attorneys for Appellants.