Florida Turnpike Restaurants Ordered to Desegregate in Quick Ruling

Press Release

March 23, 1962

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Florida Turnpike Restaurants Ordered to Desegregate in Quick Ruling, 1962. c5323ff4-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9c1a796b-aa0b-4daf-ab66-dcc3b285807d/florida-turnpike-restaurants-ordered-to-desegregate-in-quick-ruling. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

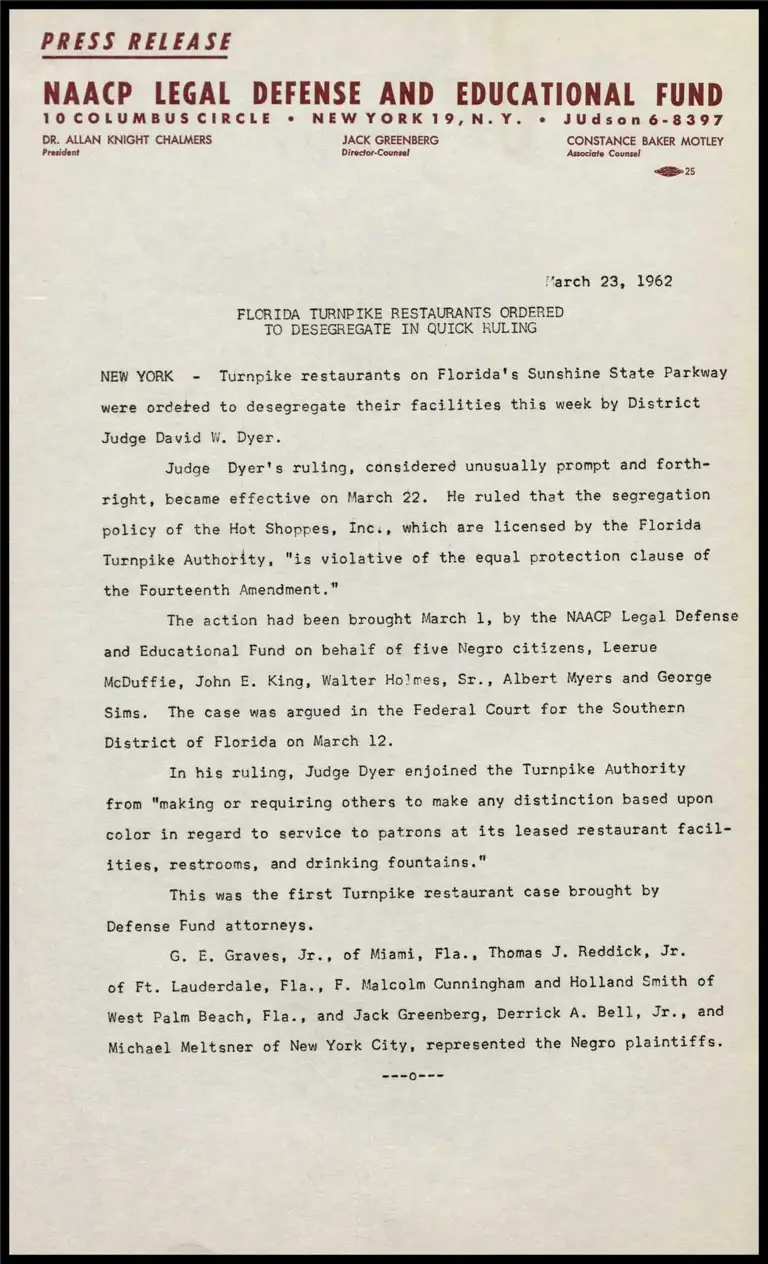

PRESS RELEASE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

1O COLUMBUS CIRCLE *+ NEW YORK19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS JACK GREENBERG

President

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY

Director-Counsel Associate Counsel

S25

March 23, 1962

FLORIDA TURNPIKE RESTAURANTS ORDERED

TO DESEGREGATE IN QUICK RULING

NEW YORK - Turnpike restaurants on Florida's Sunshine State Parkway

were ordeted to desegregate their facilities this week by District

Judge David W. Dyer.

Judge Dyer's ruling, considered unusually prompt and forth-

right, became effective on March 22. He ruled that the segregation

policy of the Hot Shoppes, Inc., which are licensed by the Florida

Turnpike Authority, "is violative of the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment.”

The action had been brought March 1, by the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund on behaif of five Negro citizens, Leerue

McDuffie, John E. King, Walter Holmes, Sr., Albert Myers and George

Sims. The case was argued in the Federal Court for the Southern

District of Florida on March 12.

In his ruling, Judge Dyer enjoined the Turnpike Authority

from "making or requiring others to make any distinction based upon

color in regard to service to patrons at its leased restaurant facil-

ities, restrooms, and drinking fountains."

This was the first Turnpike restaurant case brought by

Defense Fund attorneys.

G. E, Graves, Jr., of Miami, Fla., Thomas J. Reddick, Jr.

of Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., F. Malcolm Cunningham and Holland Smith of

West Palm Beach, Fla., and Jack Greenberg, Derrick A. Bell, Jr., and

Michael Meltsner of New York City, represented the Negro plaintiffs.

---0---