Harris v. Pulley Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harris v. Pulley Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1985. 175f4971-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9c40d398-58dc-4ccb-ac51-ebd9b3a9fad4/harris-v-pulley-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

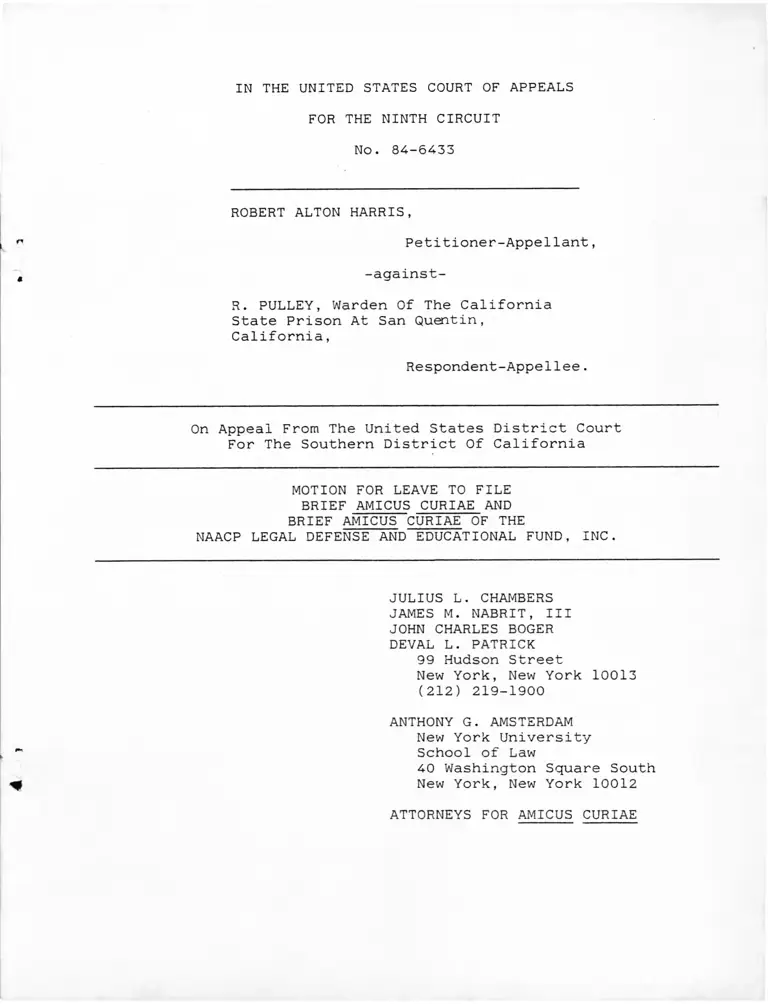

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-6433

ROBERT ALTON HARRIS,

Petitioner-Appellant,

-against-

R. PULLEY, Warden Of The California

State Prison At San Quentin,

California,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of California

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE AND

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JOHN CHARLES BOGER

DEVAL L. PATRICK

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York University

School of Law

4-0 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

ATTORNEYS FOR AMICUS CURIAE

1

2

2

7

13

14

14

15

15

15

19

25

28

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS AMICUS CURIAE

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED ......................

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ...................................

A. The History Of The Issue ................

B. The Current Status Of The Issue .........

C . The Questions Presented By The Order

Of The District Court ..............

JURISDICTION

STANDARD OF REVIEW

ARGUMENT .........

I. An Extensive Body Of Scientific

Research Provides Overwhelming

Proof That Death-Qualified Juries

Are 'Less Than Neutral' On The

Issue Of Guilt Or Innocence .............

A. The Hovey Evidence ..................

B. The Word & Sparks Evidence ..........

II. Because Death-Qualified Juries Are

Biased In Favor Of The Prosecution And

Unduly Prone To Convict, The Use of

Such Juries To Try The Guilt Or Innocence

Of Capital Defendants Violates The Sixth

And Fourteenth Amendments ...............

CONCLUSION .

STATEMENT OF RELATED CASES

APPENDIX A - Description of Empirical Studies

APPENDIX B - Article by Dr. Joseph Kadane, "Juries

Hearing Death Penalty Cases:

Statistical Analysis of a Legal

Procedure," 78 J.Am.S.A. 544

(1983)

l

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Cases:

Adams v. Texas, 4-4-8 U.S. 38 (1980)........................ 5

Ballew v. Georgia, 435 U.S. 223 (1978) .................. 28

Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625 (1980) ..................... 27

Commonwealth v. Martin, 465 Pa. 134, 348 A.2d 391

(1975) 6

Cuyler v. Sullivan, 446 U.S. 335 (1980)....................... 14

Davis v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 122 (1977)(per curiam) ....... 5

Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 ( 1979) 11

Grigsby v. Mabry, 758 F.2d 226 (8th Cir. 1985)(en banc).. 9,25,27,28

Grigsby v. Mabry, 637 F . 2d 525 (8th Cir. 1980)................ 8

Grigsby v. Mabry, 569 F. Supp. 1273 (E.D. Ark. 1983).......... 9

Hovey v. Superior Court, 28 Cal.3d 1, 616 P .2d 1301

(1980)............................................... 7,8,15

Keeten v. Garrison, 742 F .2d 129 (4th Cir. 1984).............. 10

Keeten v. Garrison, 578 F. Supp. 1164 (W.D.N.C. 1984).... 10,13,25

McCleskey v. Kemp, 753 F .2d 877 (11th Cir. 1985)

(en banc) ....................................... 11

People v. Rhinehart, 9 Cal.3d 139, 507 P.2d 642

(1973)............................................ 6

Smith v. Balkcom, 660 F.2d 573 (5th Cir. Unit B, 1981),

modified on other grounds, 671 F .2d 858

(1982)............................................ 11

Spinkellink v. Wainwright, 578 F .2d 582 (5th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 440 U.S. 976 (1979) ............ 10,25

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975) ................ 11

TABLE OF CASES (cont'd .)

Page

United States v. Harper, 729 F .2d 1216 (9th Cir. 1984).. 12

r United States ex rel. Clark v. Fike, 538 F.2d 752

(7th Cir. 1976)................................. 6 >12

United States ex rel. Townsend v. Twomey, 452

F . 2d 350 (7th Cir. 1972)....................... 6,12

Wainwright v. Witt, __ U.S.__, 83 L.Ed.2d 841 (1985).... 5,28

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968)............ 2,26,27,28

Other Authorities:

Hastie, R., Inside the Jury (Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, Mass., 1983)............................. 18

• 8 Law and Human Behavior, Nos. 1/2 (June 1984)...........

Federal Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §2241 ............................................... 14

28 U.S.C. §2253 ............................................... 14

V

iii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-6433

ROBERT ALTON HARRIS,

Petitioner-Appellant,

-against-

R. PULLEY, Warden Of The California

State Prison At San Quentin,

California,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of California

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AMICUS CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. ("the

Fund"), by its undersigned counsel, moves this Court, pursuant to

Rule 29 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, for leave to

file the annexed brief amicus curiae in support of petitioner-appellant

Robert Alton Harris.

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Fund is a non-profit corporation established to

assist black citizens in securing their constitutional rights.

In 1967, it undertook to represent all condemned prisoners in the

United States, regardless of race, for whom adequate representation

could not otherwise be found. It has frequently represented

IV

condemned inmates before the Supreme Court of the United States.

E . g . , Furman v. Georgia, 4-08 U.S. 238 (1972); Jurek v. Texas,

428 U.S. 262 (1976); Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976);

Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584 (1977); Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586

(1978); Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782 (1982); Francis v. Franklin,

_U.S. __, 53 U.S.L.W. 4495 (U.S., April 30, 1985)(No. 83-1590).

The Fund is serving as counsel for petitioners in two

recent federal cases in which death-gualification claims — virtually

identical to the claims asserted on this appeal by petitioner-

appellant Robert Harris -- have been evaluated on a full evidentiary

record. See Grigsby v. Mabry, 569 F. Supp. 1273 (E.D. Ark. 1983),

aff'd , 758 F .2d 226 (8th Cir. 1985)(en banc); Keeten v. Garrison,

578 F. Supp. 1164 (W.D.N.C.), rev'd, 742 F.2d 129 (4th Cir. 1984),

cert. pending, No. 84-5187 (filed February 2, 1985). The Fund rep

resents numerous other inmates in a number of jurisdictions, includ

ing this Circuit, who have asserted or intend to assert this consti

tutional claim.

In light of (i) the extensive experience of the Fund with

the factual and legal issues presented by this claim, and (ii) the

direct interest of clients of the Fund in the ultimate resolution

of this claim, counsel respectfully request leave to file this

brief amicus curiae.

Dated: New York, New York

July 1, 1985 Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JOHN CHARLES BOGER

DEVAL L. PATRICK

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

v

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York University

School of Law

AO Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

ATTORNEYS FOR AMICUS CURIAE

BY:

vi

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-64-33

ROBERT ALTON HARRIS,

Petitioner-Appellant,

-against-

R. PULLEY, Warden Of The California

State Prison At San Quentin,

California,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of California

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Whether the jury trial guarantee of the Sixth

Amendment and the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

prohibit the systematic exclusion for cause from a capital

defendant's guilt or innocence trial of all jurors who could

fairly and impartially try that issue, solely because their

opposition to the death penalty would make them ineligible for

service in the event of a subsequent penalty trial -- despite

extensive proof that this practice produces guilt-phase juries

that are (i) biased in favor of the prosecution, (ii) unduly

prone to convict, and (iii) unrepresentative of the communities

from which they are drawn?

2. Whether the District Court could properly reject

petitioner's claims on their factual merits without allowing

petitioner an evidentiary hearing on the important factual

issues it resolved adversely to petitioner?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A . The History Of The Issue

The constitutionality of "death-qualified" juries as

triers of guilt or innocence in capital cases was first

addressed by the Supreme Court in 1968 in Witherspoon v. Illinois,

391 U.S. 510, 520 n.18 (1968), and was left unresolved. Since

1968 it has been the subject of a large and rapidly growing body

of litigation in capital cases in the state courts and the lower

federal courts. Although it has produced conflicting opinions

from these courts, it has never been addressed by the Supreme

Court again.

The term "death-qualification" refers to the practice

of identifying and excluding from capital juries those potential

jurors whose views on the death penalty are considered incompatible

with their duties as jury members. This practice is universal in

jury trials of capital cases, and with rare exceptions those who

are excluded oppose the death penalty. It is hardly surprising

that many people have long believed that this process alters the

composition and functioning of the resulting jury in a systematic

and predictable way: that it weighs the jury against the defendant.

But belief is one thing and proof another, and until the last few years

there was no conclusive proof. In 1968 the Supreme Court was

2

asked in Witherspoon v. Illinois to hold that death-qualified

juries are unconstitutionally conviction-prone. The Court

declined to do so, finding that the empirical record before it

was too weak to form the basis for such a decision. The Court

did not rule that Witherspoon was factually wrong in his claim

that death-qualified juries are conviction-prone; rather, it with

held judgment. Addressing the preliminary drafts of some early

social scientific studies on the effects of death-qualification

which Witherspoon's attorneys had asked it to judicially notice,

id., 391 U.S. at 517, n.10, the Court found:

"The data adduced by the petitioner . . .

are too tentative and fragmentary to

establish that jurors not opposed to the

death penalty tend to favor the prosecutor

in the determination of guilt. We simply

cannot conclude, either on the basis of

the record now before us or as a matter of

judicial notice, that the exclusion of jurors

opposed to capital punishment results in an

unrepresentative jury on the issue of guilt

or substantially increases the risk of con

viction. In light of the presently available

information, we are not prepared to announce

a per se constitutional rule requiring the

reversal of every conviction returned by a

jury selected as this one was." Id., at

517-518 (fn. omitted).

The basis for this assessment was clearly and carefully

stated in footnote 11 of the Court's opinion:

"During the post-conviction proceedings

here under review, the petitioner's counsel

argued that the prosecution-prone character of

'death-qualified' juries presented 'purely a

legal question,' the resolution of which required

'no additional proof' beyond 'the facts . . .

disclosed by the transcript of the voir dire

examination . . . .' Counsel sought an oppor

tunity to submit evidence in support of several

contentions unrelated to the issue involved here.

On this issue, however, no similar request was

made, and the studies relied upon by the petitioner

3

in this Court were not mentioned. We can only

speculate, therefore, as to the precise meaning

of the terms used in those studies, the

accuracy of the techniques employed, and

the validity of the generalizations made.

Under these circumstances, it is not

surprising that the amicus curiae brief

filed by the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund finds it necessary to

observe that 'with respect to bias

in favor of the prosecution on the

issue of guilt, the record in this

case is almost totally lacking in the

sort of factual information that would

assist the Court.'" Ld., at 517-518, n.ll.

The Witherspoon Court was quite explicit in leaving open

both the factual and legal questions of conviction-proneness of

death-qualified juries. It said in so many words that these

questions were reserved for future consideration, and it invited

further research and proof on the factual question:

"Even so, a defendant convicted by such a

[death-qualified] jury in some future case

might still attempt to establish that the

jury was less than neutral with respect to

guilt. If he were to succeed in that effort,

the question would then arise whether the State's

interest in submitting the penalty issue to a

jury capable of imposing capital punishment may be

vindicated at the expense of the defendant's

interest in a completely fair determination of

guilt or innocence -- given the possibility of

accommodating both interests by means of a

bifurcated trial, using one jury to decide

guilt and another to fix punishment. That

problem is not presented here, however, and

we intimate no view as to its proper resolu

tion." Id., at 391 U.S. 520, n.18.

On the record before the Court in that case, its decision appears

to have been inescapable. Indeed, although the Witherspoon Court

was not required to, and did not so hold, the entire body of

scientific evidence available in 1968 may well have been insufficient

<4

to support a factual conclusion concerning the conviction-proneness

of death-qualified juries. Since 1968, however, the state of

knowledge on this issue has changed greatly.

While it did not reach the question of bias on the

issue of guilt, the Witherspoon Court did, of course, restrict

the permissible scope of death-qualification in order to insure

fair jury determination of the issue of penalty. Under Witherspoon,

potential jurors could be excused from service in capital cases

because of their opposition to the death penalty only if they were

unwilling to consider the death penalty in any case, or unable to

be fair and impartial in deciding the defendant's guilt. 391 U.S. at

522-23 n.21. The Court held that a jury from which venirepersons

were excused on any basis broader than these two is "a tribunal

organized to return a verdict of death," id., at 521, and that "[n]o

defendant can constitutionally be put to death at the hands of a

tribunal so selected." Id., at 522-23. This rule does not affect

the validity of any sentence other than death or the validity of a

defendant's conviction, as opposed to his sentence.

Recently, in Wainwright v.-Witt, __U.S.__, 83 L.Ed.2d 84-1 (1985)

the Supreme Court modified the constitutional limitations on death-

qualification. But while Witt changes the specific standards

that govern this practice, it "adhere[s] to the essential balance

struck by the Witherspoon decision." _Id, at n.5. Neither Witt

nor the Supreme Court's earlier cases applying Witherspoon, see

Davis v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 122 (1977)(per curiam); Adams v. Texas,

448 U.S. 38 (1980), address the present claim: that death-qualified

juries are less than neutral with respect to guilt.

5

Neither petitioner Harris nor amicus are challenging

the exclusion of veniremen who could not be fair and impartial

in deciding their guilt or innocence. Nor do they dispute the

right of the state to exclude venirepersons who could not fairly

try the issue of penalty from participation in sentencing delib

erations. Their claim is limited to the assertion that it is

unconstitutional to preclude venirepersons who would be fair

and impartial in determining their guilt or innocence from trying

that issue, solely because they would not be eligible to participate

in a possible subsequent penalty trial.

In the decade between 1968 and 1978, the courts witnessed a

steady incremental growth in the body of empirical evidence on

death-qualification: the early studies that had been presented to

the Supreme Court in preliminary form were completed, and a few

new studies were conducted. This new evidence was presented in the

lower courts in support of arguments against the constitutionality

of death-qualification, but in each case the courts held that

despite these developments, the available scientific evidence on

this point remained "tentative and fragmentary." See, e .g .,

People v. Rhinehart, 9 Cal.3d 139, 507 P.2d 642 (1973); Commonwealth

v. Martin, 465 Pa. 134, 348 A.2d 391 (1975); United States ex rel.

Townsend v. Twomey, 452 F .2d 350, 362-63 (7th Cir. 1972); United

States ex rel. Clark v. Fike, 538 F.2d 752 (7th Cir. 1976).

In 1978 and 1979, however, a large scale research project

on death-qualification was conducted under the direction of some of

the most eminent forensic social scientists in the country, and it

produced a major new set of studies on the effects of death-qual

ification on jury composition, attitudes and behaviors. These

6

studies conclusively demonstrate that death—Qualified juries

are indeed biased in favor of the prosecution, unduly prone to

convict, and unrepresentative of the communities from which they

y

are drawn.

B . The Current State of the Issue

In the past several years, lower court cases have followed

one of two irreconcilable paths: (i) some have addressed the death-

qualification issue as an empirical question and have held that death-

qualification is constitutional despite its effects on capital juries;

while (ii) some have held that this practice presents a legal issue only.

(i) Major Cases Addressing the Empirical Issue

Hovey v. Superior Court. The first appellate case that

addressed this issue on the basis of a complete factual record

including the more recent studies on death-qualification was Hovey

v. Superior Court, 28 Cal.3d 1, 616 P .2d 1301 (1980). In Hovey,

on the basis of a detailed record, the California Supreme Court

found that a death-qualified jury selected by the procedures out

lined in Witherspoon — a "Witherspoon-qualified" jury — "would

not be neutral" on the question of guilt. Hovey, supra, 28 Cal.3d

at 68, 616 P .2d at 1346. The court declined, however, to rule on

the constitutionality of death-qualification as practiced in

California, because under California law jurors may also be

excluded from capital cases for an additional reason: because they

would always vote for the death penalty in every capital case.

The court reasoned that the exclusion of these potential jurors

might, conceivably, offset the demonstrated effects of excluding

those who would never consider the death penalty. I_d. , 28 Cal. 3d

1/ These studies have been published in a special journal issue on

death-qualification, 8 Law and Human Behavior, Nos. 1/2 (June, 1984).

7

at 63-69, 616 P .2d at 1343-46. While the California Supreme

Court recognized that this group, the "automatic death penalty"

jurors, may only exist "in theory," id., 28 Cal.3d at 63, 616 P .2d

at 1343, it held that the existence, the size and the impact of

this group were factual questions on which the defendant had the

burden of proof, and it found that the record in that case did not

include any substantial evidence on this point. Therefore, the

court concluded that "until further research is done . . . this

court does not have a sufficient basis on which to bottom a consti

tutional holding" on jury selection practices in capital cases in

California. _Id. , 28 Cal.3d at 68 , 616 P.2d at 1346.

In short, the Hovey case identified one narrow factual

gap that remained to be filled in order to complete the proof of

the claim that death-qualified juries are conviction-prone.

Grigsby v Mabry. In 1980 the Eighth Circuit held that

Grigsby, a state prisoner in Arkansas, was entitled to a federal

habeas corpus hearing on his claim that the death-qualified jury

that tried him was unconstitutional. Grigsby v. Mabry, 637 F .2d

525 (8th Cir. 1980). The central question that the Court of Appeals

identified for consideration at that hearing was "whether death-

qualified jurors are more likely to convict than jurors selected

without regard for their views on the death penalty;" if that

question is answered affirmatively "Grigsby has made a case that his

constitutional rights have been violated and he would be entitled

to a new trial." Id. at 527.

8

The hearing on remand in Grigsby was conducted in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas,

and was comparable in scope to the Hovey hearing. It included

evidence on all the new studies first presented in Hovey, and it

also included extensive new evidence demonstrating that the "automatic

death penalty" group constituted only 1% to 2% of the population

nationally, and that the occasional exclusion of an "automatic

death penalty juror" from a capital case has an insignificant

impact on the demonstrated biasing effects of death-qualification.

In August of 1983, Judge G. Thomas Eisele of the Eastern District

of Arkansas filed a detailed opinion based on this record, holding

that the present form of death-qualification is unconstitutional on

two grounds: (i) that it biases capital juries against the defendants

in the determination of guilt or innocence and (ii) that it denies

capital defendants their Sixth Amendment right to a jury on the

question of guilt or innocence that is drawn from a fair cross-

section of the community. Grigsby v. Mabry, 569 F. Supp. 1273

(E.D.Ark. 1983). Judge Eiselie's opinion has now been upheld on

appeal by the Eighth Circuit en banc. Grigsby v. Mabry, 758 F .2d

226 (8th Cir. 1985)(en banc).

Keeten v. Garrison (District Court). At the district

court level, Keeten was similar to the Grigsby case both in form

and in content. The petitioners were state prisoners who claimed

in a federal habeas corpus proceeding that their constitutional

rights were violated by the use of death-qualified juries to deter

mine their guilt or innocence in the North Carolina state courts.

The evidentiary record was comparable to that in Grigsby, and*the

9

judgment of trial court judge, the Honorable James B. McMillan

of the Western District of North Carolina, was the same:

the evidence in the record answers the question posed in

Witherspoon and demonstrates that death-qualification produces

juries that are "less than neutral with respect to guilt." Keeten

v. Garrison, 578 F. Supp. 1164- (W. D. N.C. 1984). The judgment of

the District Court was reversed by the Fourth Circuit in Keeten

v. Garrison, 742 F.2d 129 (4th Cir. 1984), but the opinion of the

Court of Appeals did not rest on the factual issues, but on its

view of the law.

Thus, since 1979, every court that has considered the

entire body of empirical evidence now available has concluded that

the evidence proves what remained unproven in 1968: that death-

qualified juries are more likely to convict than ordinary criminal

j uries.

(ii) Major Cases That Reject The Empirical Issue

Spinkellink v. Wainwright. Until 1978, every court that

had considered the issue agreed that if proof could be marshalled

that such juries are more likely to convict than ordinary, fully

representative criminal juries, a constitutional violation would

be established. In 1978, in the case of Spinkellink v. Wainwright,

578 F .2d 582 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 440 U.S. 976 (1979),

the former Fifth Circuit held otherwise:

"When petitioner asserts that a death-qualified

jury is prosecution-prone, he means that a death-

qualified jury is more likely to convict than a

non-death-qualified jury . . . . Even if this is

true the petitioner's contention must fail. That

a death qualified jury is more likely to convict than

a non-death-qualified jury does not demonstrate

which jury is impartial." Id. at 594.

10

In essence, Spinkellink holds that there is no factual

issue to be decided at all: if each juror who tried the defendant

was individually "fair and impartial," nothing more can be asked.

Spinkellink flies in the face of the Supreme Court's

statement that factual proof that death-qualified juries are un

commonly conviction-prone would implicate "the defendant's interest

in a completely fair determination of guilt or innocence." Wither

spoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. at 520 n.18. Spinkellink ignores the basic

constitutional rule that a jury is not just any group of jurors who

are individually fair-minded. If that were so, juries could consist

entirely of fair-minded whites or fair-minded Democrats. A jury

must also fairly reflect the community from which it is drawn, both

in its composition, see Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975);

Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979), and in its predispositions.

This rule was applied by the Court in Witherspoon when it prohibited

juries that are "uncommonly willing to condemn a man to die." 391 U.S.

at 521. Yet Spinkellink explicitly endorses the use of juries that

are uncommonly willing to convict. Nonetheless, the holding in

Spinkellink on this issue remains the law in the present Fifth and

Eleventh Circuits, the two successor courts to the former Fifth Circuit.

See Smith v. Balkcom, 660 F.2d 573 (5th Cir., Unit B, 1981), modified

on other grounds, 671 F.2d 858 (1982). McCleskey v. Kemp, 753 F .2d 877,

901 (11th Cir. 1985)(en banc).

Keeten v. Garrison(Circuit Court). As noted, the Fourth

Circuit reversed the judgment of the District Court in Keeten without

making any attempt to resolve the factual issues raised by the

record and the opinion of the trial court judge. Instead,

11

the Circuit Court chose to follow Spinkellink, and concluded that

the conviction-proneness of death-qualified juries is of no consti

tutional consequence.

(iii) Other Federal Cases

Seventh Circuit. While the Seventh Circuit has not faced

the task of analyzing all presently available empirical evidence

on death-qualification, its position on the legal issue is clear

and it is in direct conflict with Spinkellink and its progeny:

"the decision on this issue rest[s] on empirical analysis . . . ."

United States ex rel. Clark v. Fike, 538 F.2d 750, 762 (7th Cir.

1976); see also United States ex rel. Townsend v. Twomey, 542

F . 2d 350, 362-63 (7th Cir. 1972).

Ninth Circuit. This issue has not been determined

by this Court, although the Court has previously alluded to the

question and its ramifications. See United States v. Harper,

729 F .2d 1216 (9th Cir. 1984)(Fletcher, J., concurring):

"[W]hether a verdict returned such a 'death-qualified jury' can

withstand constitutional scrutiny is a complex and difficult

constitutional question" that should not be decided before a

decision is necessary.

In sum, the Fourth, Fifth and Eleventh Circuits have

held that it is constitutional to use death-qualified juries to

determine guilt, even if they are uncommonly conviction-prone.

The Seventh Circuit has held that factual proof that death-qualified

juries are conviction-prone would require a holding that the

practice is unconstitutional. The Eighth Circuit has recently held

that such a demonstration has been made,and has outlawed the practice.

12

The matter is before this Circuit on petitioner Harris' appeal; the

remaining circuits have not yet been obligated to face this question.

C . The Questions Presented By The Order of the District Court

The District Court addressed and analyzed

petitioner Harris' death-qualification claim as an empirical

issue. In other words, it accepted the overall analytical

framework set forth in Hovey, and determined that Harris

was obligated to prove two things: first, that Hovey

itself correctly evaluated the death—qualification studies

and their results; and second, that Dr. Kadane's additional

2/

study presented in Word & Sparks filled the one evidentiary

gap — concerning the size and significance of the so-called

"automatic death penalty" group of prospective jurors ("ADPs")

_ identified by the Supreme Court of California in Hovey.

The District Court proceeded to bypass the first

question, the accuracy of Hovey, and decided as a matter of

fact, without any evidentiary hearing, that Dr. Kadane's

evidence was insufficient to make Hovey whole. By contrast,

the District Court that received the Kadane evidence in Keeten

v. Garrison, 578 F. Supp. 1164-, 1175-77 (W.D.N.C. 1984-) ,

found it "credible, consistent, and essentially uncontradicted.

Id. at 1177. Yet the District Court here rejected that same

evidence without any adversary testing of Dr. Kadane's

testimony.

2/ See discussion of the Word & Sparks evidence at pages 19-

25, infra.

13

JURISDICTION

The District Court had subject matter jurisdiction

of this case pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §224-1. This Court has juris

diction on appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §2253. The District

Court's memorandum decision and order was filed on October

17, 1984; it is final and appealable to this Court. A timely

notice of appeal was filed on November 14, 1984.

STANDARD OF REVIEW

The death-qualification claim asserted by petitioner

Harris and addressed in this brief by amicus curiae raises

questions of federal statutory and constitutional law and

mixed questions of law and fact requiring independent, de

novo review by this Court. See, e . g ., Cuyler v. Sullivan,

446 U.S. 335, 341-42 (1980).

ARGUMENT

I

AN EXTENSIVE BODY OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

PROVIDES OVERWHELMING PROOF THAT DEATH-

QUALIFIED JURIES ARE 'LESS THAN NEUTRAL'

ON THE ISSUE OF GUILT OR INNOCENCE______

A . The Hovey Evidence

The District Court did not explicitly pass upon the

validity of the California Supreme Court's findings in Hovey

v. Superior Court, 28 Cal.3d 1, 616 P.2d 1301 (1980), but even

a cursory review of the scientific evidence reveals that those

findings were compelled by an overwhelming and one-sided record.

Attitudinal and Demographic Surveys

The Hovey record includes five surveys that study the

attitudinal and demographic characteristics of the jurors who are

_3/

excluded from service by the process of death-qualification.

These surveys uniformly find that jurors who are now permitted

to serve in capital cases hold attitudes that are more hostile

to the defendant and more favorable to the prosecution than the

attitudes of those who are excluded. The surveys also uniformly

find that women and blacks are disproportionately excluded by

death-qualification.

Conviction-Proneness Studies

Six studies in the Hovey record examine the voting behavior

of death-qualified jurors and of those who are excluded by death-

±J

qualification, in actual and in simulated criminal trials. These

_3/ A more complete description of each attitudinal study appears

in Appendix A at 1-6.

V See Appendix A at 6-11.

- 15 -

range from a study by Professor Hans Zeisel of the votes of

actual jurors in felony trials in Brooklyn and Chicago, to

studies of responses of college students in Georgia and of

industrial workers in New York, to a sophisticated trial

simulation using jury-eligible adults in California. In each

instance the results are the same: death-qualified jurors

are more likely to convict than those who are excluded from

capital juries because of their opposition to the death penalty.

Studies Of The Mechanisms That Produce

__________ The Biasing Effects___________ _

Several of the studies in the record examine how the

removal of opponents of the death penalty pursuant to Witherspoon

_5/

changes the functioning of a jury. These studies show that

death-qualified jurors are more likely than those who are

excluded to believe prosecution witnesses and to disbelieve

defense witnesses, that differences in voting behavior between

these two types of jurors persist after jury deliberations, and

that the exclusion of jurors who would not consider voting for

the death penalty adversely affects the quality of jury delibera

tions. In addition, one study (the Haney Study) demonstrates

that the process of death-qualification — the questioning of

potential jurors at the outset of a capital trial on their

attitudes toward the death penalty, and the removal of those

who are unwilling to consider imposing the death penalty —

predisposes even those jurors who are permitted to serve to

believe that the defendant is guilty.

5/ See Appendix A at 12-14.

16

Three overall points about this record deserve brief

mention. First, it is noteworthy that so many studies, conducted

over a long period of time by different researchers in different

locations, using various methodologies and varying subject pools,

have all found the same thing: death-qualified juries are more

likely to convict than ordinary criminal juries. As Professor

Hans Zeisel explained in his testimony in this record:

"The reason I have put these six studies

together is the following, namely, I'm

sure that it couldn't escape anybody who

has listened to this testimony . . . the

almost monotony of the results. It is

obviously the same whether you take the

experiment at Sperry-Rand in New York or

students in Atlanta or jurors in Chicago

or Brooklyn or eligible jurors here in

Stanford; it comes always out the same

way.

"And Your Honor, I should add that it

happens seldom in the social sciences

that the problem is being studied even

twice, not to speak of six times . . . .

"So this is an unusual fact. And since

all of the studies show the same result,

no matter with whom, no matter with what

stimulus, no matter with what closeness

of simulation, there is really one con

clusion that we can come to. The re

lationship is too robust -- and this is

a term of art among scientists -- that

no matter how strongly or how weakly

you try to discover it in terms of your

experimental design, it will come through."

(Hovey RT 8A-85.)

Second, the studies are of high quality. The body of

empirical research on death-qualification includes studies by

such eminent social scientists as Professor Hans Zeisel and

Professor Phoebe Ellsworth, and surveys by such nationally

17

known organizations as Louis Harris Polls and the Field Research

Corporation. This research has been enthusiastically reviewed

by, among others, Professor Reid Hastie, author of the most ex

tensive work on jury functioning in recent years, Inside the Jury

(Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1983). The most recent

studies -- those conducted after 1978 -- are of particular note.

They are exemplary in their methodology and they are tailored to

address the exact legal issue at stake. The subjects in each of

these studies were classified on the basis of their attitudes

toward the death penalty using questions based on Witherspoon,

and the two Witherspoon-excludable groups -- those who would never

consider voting for the death penalty and those who would not be

fair and impartial on guilt or innocence in a capital case -- were

identified separately. In each study, the subjects who could not

be fair and impartial on guilt were excluded from consideration.

As a result, these studies directly demonstrate the biasing effects

of excluding potential jurors who would be fair on guilt but who

would never consider voting for the death penalty, after those who

would not be fair and impartial on guilt have already been removed.

Third, there are no studies whatever that reach a contrary

conclusion. The views on both sides were thoroughly aired in the

testimony in the record, and the criticisms failed to sway the

courts that evaluated this body of research on its merits. One of

the major reasons for the conclusions of the Hovey court is the

fact that after sixteen years and a dozen or more studies, nothing

has ever been shown to contradict the uniform finding that death-

qualification biases juries against the defendant. To quote

Professor Zeisel's testimony once more:

18

"But I just want to say, given the difficulties

of coming to conclusions about human nature, I

would say that there are few things about which

I am so certain than this relationship between

death-qualification and the tendency to vote guilty.

And it is supported by the attitude studies. I

don't see how one can sensibly come to doubt it.

You see, these cross-examinations, if you will

forgive me, have gone on now for 15 years, and

nobody has ever produced a study which shows

that this is not true." (Hovey, RT, 163-64.)

B . The Word and Sparks Evidence

The Word & Sparks record consists, essentially, of

the expert testimony of Dr. Joseph B. Kadane, an eminent professor

of statistics at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsyl

vania, and exhibits offered in support of that testimony. Dr.

Kadane reanalyzed two of the key Hovey studies -- the Ellsworth

Conviction-Proneness Study and the Ellsworth Attitude Survey -- in

light of two more recent surveys: (i) a 1981 Field Research Corpora

tion Survey that found that 12.6% of the fair and impartial jury-

eligible population of California would never consider imposing the

death penalty in any capital case; and (ii) a 1981 Harris Poll that

found that 1% of the national adult population who could be fair and

impartial would always vote for the death penalty in any capital case.

0 J

(These surveys are described in Exhibit I to the Harris petition.)—

Essentially, Dr. Kadane's analysis answers the following

question: given the size of the "guilt phase nullifier" group

(couldn't be fair and impartial on guilt-or-innocence in a capital

case), the "guilt phase includable" group (could be fair and im

partial on guilt-or-innocence, but could never consider imposing

death), and the "Witherspoon-qualified" group (could consider

6/ An article written by Dr. Kadane describing his studies is annexed

as Appendix B to this brief, for the convenience of the Court.

19

imposing death) -- all found by the 1981 Field Survey -- and given

the size of the "automatic death penalty" group (would always give

death to a convicted capital defendant) found by the 1981 Harris

Survey, what effect does the exclusion of "automatic death penalty"

jurors from capital juries have on the findings of the Ellsworth

Attitude Survey and the Ellsworth Conviction-Proneness Survey, as

applied to the population of California venirepersons?

Dr. Kadane "had to assume something about the behavior

[and attitudes] of the automatic death penalty group" (Word & Sparks

RT 56) since they "were not directly measured" by the two prior

Ellsworth studies. (Kadane Study, Exh. B, No. 6, at 19). Kadane

took "the most conservative stance on this issue" (id.), and assumed

that the automatic death penalty group "would be as strongly opposed

to the defense as it could be on each issue, [and as] strongly pro

prosecution as it could be on each issue." (Word &■ Sparks RT 56) .

Specifically, he assumed that they would take the most pro-prosecution

position on each question in the Ellsworth Attitude Survey, and "that

they would vote, all of them, to convict in the behavior experiment

[the Ellsworth Conviction-Proneness Study]." (Id.) This assumption

therefore weights Dr. Kadane's results against the position urged

by petitioner:

"By assuming that the group who would ALWAYS

impose the death penalty have the most extreme

views in favor of the prosecution, I am making

it as difficult as I can to show that the amal

gamated ALWAYS and NEVER group is nonetheless

more pro defense, less pro prosecution than the

remainder. So what this means is that my estimate

of the bias will be too low, that is, if I had

accurate data on the views of the group that

would ALWAYS impose the death penalty, they will

not be as extreme as what I have assumed. I don't

20

know by how much. Consequently, my estimate

of the odds of bias will be lower, lower in the

calculations that I do here than they would be

if I had better data by an amount . . . [that]

I don't know. So I am making the assumption

that is most conservative, most in accord with

[the prosecution's] interest rather than [the

defense's] in the sense that the numbers that

I am calculating will . . . tend to show less

bias than they would if I had data on this

question." (Id. at 57; emphasis added.)

Using these assumptions, Dr. Kadane calculated the effect

of excluding "automatic death penalty" jurors on the findings of the

Ellsworth Attitude Survey and the Ellsworth Conviction-Proneness

Z fStudy. The results, with respect to the Ellsworth Attitude Survey

are set forth in Table 5 of the Kadane Study (Exhibit B, No. 6,at 22;

see Figure A). (The form of this table is identical to that of

Table 2 of the Kadane Study (see Figure 2).) Dr. Kadane states:

"I conclude from Table 5 a showing of substantial bias against

the defense from the current procedure." (Kadane Study, Exhibit B,

No. 6, p . 21.)

With respect to the Ellsworth Conviction-Proneness Study,

Dr. Kadane reports:

"The showing of substantial bias in the

Ellsworth and Fitzgerald study is con

firmed by the reanalysis of the Ellsworth,

Thompson and Cowan experiment. Here $

is 1.519 (so the estimated odds of NEVER

or ALWAYS juror being more favorable to

the defense than a SOMETIMES AND SOMETIMES

NOT juror is more than 3 to 2), with a

standard deviation of .228, which means that

((f) -1)/SD = 2.27. Hence, the probability

of neutrality or bias against the prosecution

( $ ^ 1) is 1.3%. Pgain we have a finding

of substantial bias against the defense."

(Kadane Study, Exhibit B , No. 6, at 21) .

7/ The mathematical calculations involved are discussed in the

Kadane Study (Exhibit B, No. 6) at pp. 18-19 and 26-40; a minor

technical issue ("effective sample size") is discussed at 20-

21 (see RT 58).

- 21 -

Comparing these data to the original findings of the Ellsworth

Conviction-Proneness Study, Dr. Kadane stated: "They are very

similar. The estimated odds drop from 1.65 to 1.52, which is

a very slight drop." (RT 66.)

The underlying reason for these findings is described

at the conclusion of the Kadane Study:

"What makes all the results true is that the

ALWAYS group is so small (1% of the population)

that the ALWAYS or NEVER group is dominated by

the NEVER part, and the AT LEAST SOMETIMES group

is dominated by the SOMETIMES AND SOMETIMES NOT

majority. Even attributing the least favorable

views to the ALWAYS group does not disturb the

finding of substantial bias against the defense."

(Exhibit B, No. 6, at 23.)

Dr. Kadane calculated the effect of excluding the

the "automatic death penalty" group using data from the Ellsworth

Attitude Survey and the Ellsworth Conviction-Proneness Study be

cause "they are the most recent and most thorough of their respec

tive types." (Kadane Study, Exhibit B, No. 6, at 4.) He testified,

however, that the same general conclusions would apply to the findings

of the other studies on death-qualification. (Words 6 Sparks RT 68.)

The linchpin of the District Court's order is its

rejection of Dr. Kadane's finding. This rejection is based on three

grounds, all untenable. First, the District Court complains that

Dr. Kadane 'performed no original research.' (Order, p. 7). The

significance of-this criticism is not apparent. Dr. Kadane may not

have interviewed research subjects personally, but he testified

about a major new study of death-qualification that he conducted.

His study does reanalyze the data of earlier studies, but it

does so on the basis of two new surveys that provide new data

addressed to the issue left open in Hovey.

22

Second, the District Court speculates that the

proportion of automatic death penalty jurors (ADPs) may in fact

be higher than the 1% that Harris found. There is no evidentiary

basis for this speculation. The Court cites a reference in Hovey

to a possible ADP figure over 25%; in fact that figure comes from

a study that does not measure ADPs. In any event, the proportion

of ADPs is a factual question — put in dispute by the pleadings

̂/

It cannot be decided without evidence.

8/ The prosecutor at the Word 8 Sparks hearing faulted Dr. Kadane

for not using the Jurow Study, or Smith, A Trend Analysis of Attitudes

Toward Capital Punishment, 1936-1974 (1975) for their data on the

size of the "automatic death penalty" group. (Word & Sparks RT 89-95.)

This is an empty criticism.

Dr. Kadane explained why he used Harris 1981 rather than Jurow's

finding of 2% automatic death penalty jurors: "The Harris study,

being as it was done by a national polling organization, done under

very strict standards . . . is a very reliable thing for me to use.

I had confidence in that study, and that's why I used it." (Id. at

93-94.) In comparison to the Jurow Study, "the Harris study, it

seemed to me, was the sounder work." (_Id. at 94.) The Hovey court

concurred. Jurow's finding that "2 percent of his 211 subjects fell

into the 'automatic death penalty' category . . . did not afford a

reliable basis for generalizing to the percentage of such jurors

in the entire population, since . . . [it] was [not] based on a

random sample of the population." (28 Cal.3d at 64 n.lll; see also

id.., at 63 n.109 and accompanying text.) (Jurow's finding was

based on interviews with 211 workers at one plant.)

Dr. Kadane stated that he had not read the Smith study. (Word

& Sparks RT 89-95.) However, the Smith study -- which was before

the court in Hovey -- contains only "tentative indications" as to

the number of automatic death penalty jurors (28 Cal.3d at 64); it

has no data on the issue, as the Hovey opinion reflects. The

"suggestion" in Smith relating to this question (see id., at 64,

n. Ill) is contained in data from a 1973 Harris poll (see Smith,

supra, Appendix 2 for the text of the relevant questions) which

merely indicate that 28% of the 1973 national sample favored

the death penalty for all persons convicted of first degree

murder. The 1973 Harris survey contains no indication of how many

of these people, as jurors, would have personally voted for the

death penalty, automatically, in every capital case, much less

how many of them would have done so in the face of explicit legal

23 [cont'd .]

Third, the District Court then argues that Dr. Kadane's

conclusions are untrustworthy because he has no data on the "be

havioral characteristics that an always-death group might possess,"

and the Court speculates that this group might have a disproportionate

impact if it "tended to vote in a unified fashion." (Order at 8).

This is plain error. Dr. Kadane assumed that this group would vote

in a unified fashion, and that it would be as pro-prosecution as

possible. His findings of bias are reliable precisely because he

makes such a conservative assumption, and therefore necessarily

understated the bias that the process of death-qualification produces.

The District Court completely missed this important point.

The basic problem with the District Court's evaluation of

Dr. Kadane's research is that the Court purports to resolve contested

factual issues without a hearing. The errors the Court makes — its

remarkable oversights and extreme misinterpretations of the evidence

— are classic examples of the most basic reason why such in camera

fact finding is prohibited: because it leads almost inexorably to

error. In this case the errors are all the more glaring because they

contrast harshly with the actions of other federal courts faced with

the identical issue. Evidence that was rejected here without a

instructions to them, as jurors, to consider all possible penalties.

Faced with this evidence, the court in Hovey concluded that "there

is no reliable data" on the size of the automatic death penalty

group. (I_d. , at 6k.)

2k

hearing was found to be valid and reliable after a hearing by

another federal court, Keeten v. Garrison, supra, 578 F. Supp.

at 1175-77; and while the District Court here speculates that

there may be more ADPs than the 1% Dr. Kadane estimated, other

federal courts — examining Dr. Kadane's underlying data in

light both of competing evidence and of testimony on direct and

cross-examination — found that the number of ADPs is negligible.

Grigsby v. Mabry, supra, 558 F. Supp. at 1308, aff'd , 758 F.2d at

238. The Court's key factual assumptions are thus unwarranted.

II

BECAUSE DEATH-QUALIFIED JURIES ARE BIASED IN

FAVOR OF THE PROSECUTION AND UNDULY PRONE TO

CONVICT, THE USE OF SUCH JURIES TO TRY THE

GUILT OR INNOCENCE OF CAPITAL DEFENDANTS

VIOLATES THE SIXTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS

Although the District Court does not refer to this issue,

other circuits have held that the fact that death-qualified juries

may be biased in favor of the prosecution and unduly prone to con

vict is of no constitutional significance. The leading case in this

line is Spinkellink v. Wainwright, 578 F.2d 582, 594- (5th Cir. 1978).

If it disposes of the factual and procedural questions and ultimately

reaches the legal merits on this appeal, we urge this Court to

reject such an erroneous view of the Sixth Amendment. As noted

earlier, the Fifth Circuit held in Spinkellink that

"[w]hen petitioner asserts that a death-

qualified jury is prosecution-prone, he

means that a death-qualified jury is more

likely to convict than a non-death-qualified

jury . . . . Even if this is true the peti

tioner's contentions must fail. That a

death-qualified jury is more likely to convict

than a non-death-qualified jury does not

demonstrate which jury is impartial."

(Id. at 594.)

25

With due respect to the Fifth Circuit, the argument does not make

sense. If ordinary, non-death-qualified juries are acquittal-

prone and unfair, why are they used in all criminal trials except

capital cases? Could a State seriously contend that it would not

have received a fair trial if petitioner had been tried for non

capital murder, because his jury would have been acquittal-

prone? The issue here is whether a State can increase a defendant s

chances of conviction -- tip the balance on guilt or innocence

by placing him on trial for a capital crime, rather than a non

capital one, and then death-qualifying the guilt-or-innocence jury.

Such an argument, moreover, is squarely refuted by Wither-

spoon. The Supreme Court in Witherspoon condemned the systematic

exclusion of opponents of the death penalty from capital juries be

cause it "stacked the deck against the petitioner" on the issue

of penalty. 391 U.S. at 523. If an inordinate tendency to prefer

a particular outcome were constitutionally acceptable, the Supreme

Court would not have condemned this practice. However, the Court

recognized that a jury must express the "conscience of the

community," id. at 519, and that its performance must be measured

against the yardstick of that community. Pre-Witherspoon juries

failed that test because they were "uncommonly willing to condemn

a man to die." Id., at 521.

The Spinkel1 ink position necessarily implies that a

lesser standard of reliability governs determinations of guilt

in capital cases than do determinations of penalty -- that a jury

"uncommonly willing" to convict on capital charges is

26

constitutional despite the holding in Witherspoon. There is no

justification for this distinction, and it is directly refuted

by Witherspoon itself. The Court there recognized that a de

fendant might someday prove that death-qualified juries are

guilt-prone, and stated:

"If he were to succeed in that effort, the question

would then arise whether the State1s interest in

submitting] the penalty issue to a jury capable of

imposing capital punishment may be vindicated at the

expense of the defendant's interest in a completely

fair determination of guilt or innocence -- given

the possibility of accommodating both interests by

means of a bifurcated trial, using one jury to decide

guilt and another to fix punishment."

391 at 520 n .18 (emphasis added). The Supreme Court's question,

we submit, is rhetorical: the State's interest in using a single

jury in capital cases cannot possibly outweigh the right to a

fair trial. The Eighth Circuit addressed and disposed of the

Spinkellink argument in Grigsby v. Mabry:

"We feel the reasoning of Spinkellink

. . . fails to analyze or decide the

fundamental issue . . . The issue is

not whether a jury would be biased one

way or the other, but whether an impartial

jury can exist when a distinct group in the

community is excluded by systematically

challenging them for cause. As the district

court noted, the petitioners were not seeking

_9_/

9/ In Beck v. Alabama, 4.27 U.S. 625 (1980), the Supreme Court

has expressly held that the higher standard of procedural fairness

required at the penalty phase of the capital trials extends to

the guilt-or-innocence phase as well: "To ensure that the

death penalty is indeed imposed on the basis of 'reason rather

than caprice or emotions,' we have invalidated procedural rules

that tended to diminish the reliability of the sentencing

determination. The same reasoning must apply to rules that

diminish the reliability of the guilt determination." Id. at

638 (emphasis added).

27

a jury composed entirely of [Witherspoon

excludables]; what petitioners sought was

a 'jury drawn from the entire cross section

of the community as a whole, including both

those who strongly favored the death penalty

and those who strongly opposed it.'"

Grigsby v. Mabry, supra, 758 F.2d at 24-0-4-2.

CONCLUSION

When Witherspoon was decided in 1968, the evidence

on the possible bias of death-qualified juries was "too tentative

and fragmentary. " Witherspoon v. Illinois, supra, 391 U.S. at 517

n.10. Since that time, however, the scientific evidence has be

come definite and whole, and totally one-sided. It has convinced

two federal district courts; it is the basis for a major en banc

decision by the Eighth Circuit; and it will likely be soon re

viewed by the Supreme Court. See Witt v. Wainwright, __U.S. __,

8k L .Ed.2d 801 (Marshall & Brennan, JJ., dissenting from denial

of certiorari)("This Court is certain to grant certiorari in the

immediate future to resolve this issue.")

It would be appropriate and correct for this Court to

accept the factual findings of the Eighth Circuit and follow

Grigsby v. Mabry. The Supreme Court expressed some concern in

Witherspoon that the studies adduced there had not been presented

initially at the trial court level, see 391 U.S. at 517 n.ll.

Similarly, several justices in Ballew v. Georgia, 4-35 U.S. 223

(1978) were troubled that studies relied upon there by the

majority had never been "subjected to the traditional testing

mechanisms of the adversary process." 4-35 U.S. at 24-6. But the

28

overwhelming evidence here has been thoroughly tested in a

number of lower courts, and it may not be necessary for every

court that faces this claim to hear it again at the trial

level.

It would be inappropriate, however, to rely upon the

present record to reject petitioner's factual contentions. The

District Court's adverse findings are the product solely of

surmise and speculation, not adversary testing. If the Court

concludes that the Grigsby and Word & Sparks records do not yet

constitute a sufficient factual foundation upon which to base

its legal conclusion, the case should be remanded so that full

evidence may be presented on the factual issues that remain in

dispute.

Dated: New York, New York

July 1, 1985

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JOHN CHARLES BOGER

DEVAL L. PATRICK

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York University

School of Law

4-0 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

(212) 598-2638

ATTORNEYS FOR AMICUS CURIAE

STATEMENT OF RELATED CASES

Amicus curiae is not aware of any cases currently

pending in this Court which related to the issues it has

addressed in this brief.

30

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I am counsel for amicus

curiae NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., and

that I served the annexed motion for leave to file brief

amicus curiae and brief amicus curiae on the parties to

this action, by placing copies in the United States mail,

first class mail, postage prepaid, addressed as follows:

Michael J. McCabe, Esq.

108 Ivy Street

San Diego, California 92101

Charles M. Sevilla, Esq.

1010 Second Avenue, Suite 1001

San Diego, California 92101

Michael Wellington, Esq.

Office of the Attorney General

110 West "A" Street, Suite 700

San Diego, California 92101

All parties required to be served have been served.

Done this 1st day of July, 1985.

P /; /I

/ ,6'

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX A

This Appendix is provided for the convenience of the

Court to summarize the major studies on death-qualification that

have been presented to the courts. The studies are divided into

four major categories: (i) studies on the relation between sub

jects' death penalty attitudes and their demographic characteristics

and other criminal justice attitudes (pages 1-6, infra);

(ii) studies on the relation between subjects' death penalty

attitudes and their behavior as jurors in actual or simulated

trials (pages 6-14,infra); (iii) other related studies on the

relationship between death penalty attitudes and behavior in

capital cases (pages 11-14,infra); and (iv) studies on the incidence

of "automatic death penalty jurors" in the population (pages 14-15,

infra).

I. ATTITUPINAL AMD DEMOGRAPHIC SURVEYS

1. BRONSON - COLORADO, 1970

AUTHOR: BRONSON, Edward C.

TITLE: "On the Conviction Proneness and Representativeness of

the Death-Qualified Jury: An Empirical Study of Colorado

Veniremen," 42 Colo. L. Rev. 1 (1970).

CITATIONS: Hovey v. Superior Court, 28 Cal.3d 1, 43-44,_616^P^

2d 1306, 1327-28 (1980); Grigsby v. Mabry, 569 F. Supp. 1273, 1293-

94 (E.D. Ark. 1983); 758 F .2d 226, 232 (8th Cir. 1985)(en banc);

Keeten v. Garrison, 578 F. Supp. 1164, 1172 (W.D.N.C. 1984).

SUMMARY:

This was the first study to examine the relationship

between death-penalty attitudes and other attitudes relating to the

administration of criminal justice. The respondents in this survey

were 718 Colorado venirepersons. Each respondent was asked

whether he or she "strongly favor[ed]," "favor[ed]," "oppose[d]"

or "strongly oppose[d]" the death penalty. Each respondent

was also asked five questions about his or her attitudes on

criminal justice issues. Interviews were carried out, in

person and by telephone, by trained students from the University

of Colorado, in 1968 and 1969. The Bronson-Colorado, 1970 survey

shows a consistent correlation between attitudes on the death

penalty and attitudes on other criminal justice issues. On

each of the five questions, the stronger the respondent's

support for the death penalty (as measured on Bronson’s four-

point scale), the stronger their support for positions most

favorable to the prosecution.

2. BRONSON - CALIFORNIA, 1980

AUTHOR: BRONSON, Edward C.

TITLE: "Does the Exclusion of Scrupled Jurors in Capital Cases

Make the Jury More Likely to Convict? Some Evidence from California,

3 Woodrow Wilson L. Rev. 11 (1980).

CITATIONS: Hovey, 28 Cal.3d at 47-4-9, 616 P . 2d at 1330-33; Grigsby,

569 F. Supp. at 1293-94; 758 F .2d at 232-33; Keeten, 578 F. Supp. at

1172-73.

SUMMARY:

The studies grouped together in Bronson - California, 1980

are similar in methodology and results to the Bronson - Colorado, 1970

survey. The first of these studies, Bronson/Butte County, 1980, was

conducted in 1969-1970. Seven hundred and fifty-five people from

Butte County, California jury venires were interviewed over the

telephone by students at the California State University at Chico.

As in Bronson - Colorado, 1970, respondents were asked to indicate

their position regarding the death penalty on a scale from "strongly

2

They were also asked whether theyfavor" to "strongly oppose."

agreed or disagreed with seven statements: five that were nearly

identical to the one used in Bronson - Colorado, 1970, and two

additional criminal justice items. The findings of the Butte County

survey closely parallel those in Bronson - Colorado, 1970: the

stronger the endorsement of the death penalty, the higher the level

of agreement with pro-prosecution statements.

Following the Butte County study, Professor Bronson admin

istered a slightly modified questionnaire to a sample of 707 venire-

persons from Los Angeles, Sacramento and Stockton, California.

(Bronson - Los Angeles, 1980). These interviews were carried out in

late 197k and early 1975. Once again, the data showed a consistent

pattern: the more strongly the respondents favored the death penalty,

the more likely they were to endorse pro-prosecution positions, and

there were marked attitudinal differences between the "sbrcngly

oppose" group and the other three groups combined.

In a followup survey on some kOO Butte County prospective

venirepersons in June 1971, Bronson found that 93% of those who

"strongly opposed" the death penalty would be legally excludable

under Witherspoon.

3. HARRIS, 1971

AUTHOR: LOUIS HARRIS & ASSOCIATES, INC.

TITLE: Study N.o. 2016 (1971).

CITATIONS: Hovey, 28 Cal.3d at k5-k7, 616 P .2d at 1328-30; Grigsby,

569 F. Supp. at 1293-9k; 758 F .2d at 233; Keeten, 578 F. Supp. at

1173-7k.

SUMMARY:

Harris, 1971 is a detailed national opinion survey on

attitudes toward the death penalty, and the first study in which

3

a direct comparison can be made between respondents who are death-

qualified and those who are excluded by Witherspoon criteria. It

was administered in person to a representative sample of 2,068

respondents drawn from the adult population of the United States in

1971.

The findings of the Harris, 1971 survey parallel those of

the Bronson surveys, and greatly extend them. In response to dozens

of questions on their attitudes toward various aspects of the crim

inal justice system, death-qualified respondents were consistently

more likely to favor the prosecution's position than Witherspoon-

excludable respondents. Harris, 1971 also found that more blacks

than whites would be excluded from jury service by death qualifica

tion (4-6% vs. 29%), and more women than men (37% vs. 24%). (Harris,

1971 also collected data on the voting behavior of the respondents

as jurors in criminal trials; see infra, at g-io).

4. NATIONAL POLL DATA

AUTHOR: LOUIS HARRIS & ASSOCIATES, INC.: AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR

PUBLIC OPINION (Gallup); AND NATIONAL OPINION RESEARCH CENTER

TITLE: Various national polls from 1953 through 1978 partially

summarized in: Smith, Tom W. "A Trend Analysis of Attitudes

Toward Capital Punishment, 1936-1974," in James A Davis (ed.)

Studies of Social Change Since 1948, National Opinion Research

Center, Report 127B, Chicago (1976).

CITATIONS: Hovey, 28 Cal. 3d at 54-57, 616 P .2d at 1337-39.

SUMMARY:

Numerous surveys of the national population have established

two major demographic facts about attitudes toward the death penalty:

(1) Since 1953, women have consistently opposed the death penalty in

greater proportions than men. (2) Since 1953, blacks have consistently

opposed the death penalty in greater proportions than whites and that

racial gap has grown steadily, from a difference of 8% in 1953 to 27%

in 1978.

4

5. ELLSWORTH ATTITUDE SURVEY, 1979

AUTHORS: ELLSWORTH, Phoebe C.; and FITZGERALD, Robert

TITLE: "Due Process vs. Crime Control: Death Qualification and

Jury Attitudes," published in 8 Law and Human Behavior, Issue 1-2, pp.

31-53 (198A).

CITATIONS: Hovey, 28 Cal.3d at 50-54, 616 P .2d at 1333-37; Grigsby,

569 F. Supp. at 1293-94; 758 F .2d at 233; Keeten, 578 F. Supp. at

1171-72.

SUMMARY:

The Ellsworth Attitude Survey, 1979 is the most sophisticated

of the surveys that have examined the relationship between death-qual

ification and juror attitudes. The respondents in the Ellsworth

Attitude Survey, 1979 were a probability sample of 811 jury-eligible

adult residents of Alameda County, California, in 1979. The sample

was drawn, and the subjects interviewed, by the Field Research Corpora

tion of San Francisco, an independent professional polling organization.

The respondents in the Ellsworth Attitude Survey, 1979 were

asked carefully tailored questions that embody the two prongs of the

Witherspoon standard: whether they would consider voting to impose

the death penalty, and whether they could be fair and impartial in

determining guilt or innocence in a capital case. Respondents who

could not be fair and impartial ("nullifiers") were excluded from

the analysis; of those who could be fair and impartial (717 out of the

total of 811), 17.2% were Witherspoon excludable. Respondents were

asked 13 attitudinal questions on criminal justice issues; on each,

death-qualified respondents were more favorable to the prosecution,

more crime-control oriented, and less concerned with constitutional

protections for suspects than were excludable respondents. Most

differences were sizeable and highly statistically significant. The

5

survey ctXso found that more blacks than whites are excluded by

death-qualification (25.5% vs. 16.5%), and more women than men

(21% vs. 13%).

6. PRECISION RESEARCH, 1981

AUTHOR: PRECISION RESEARCH, INC.

TITLE: Precision Research Survey

CITATIONS: Grigsby, 569 F. Supp. at 1294; 758 F .2d at 233.

SUMMARY:

In June, 1981, Precision Research, Inc., a polling

organization in Little Rock, Arkansas, conducted a state-wide

survey of death penalty attitudes using a representative sample

of 407 respondents drawn from the adult population of the State

of Arkansas. This survey used the same death penalty questions

that had been used in the Ellsworth Attitude Survey, 1979. It

found that (i) approximately 11% of Arkansas adults who could be

fair and impartial in determining guilt or innocence in a capital

case are excludable under Witherspoon because they would never

consider voting for the death penalty; (ii) among those who would be

fair and impartial, more blacks than whites are excludable in Arkansas

(29% vs. 9%); and (iii) more women than men (13% vs. 8%).

II. CONVICTION-PRONENESS STUDIES

1. ZEISEL, 1968

AUTHOR: ZEISEL, Hans

TITLE: "Some Data on Juror Attitudes Toward Capital Punishment,"

Monograph, Center for Studies in Criminal Justice, University of

Chicago Law School (1969).

CITATIONS: Hovey, 28 Cal.3d at 27-30, 616 P .2d at 1315-17; Grigsby,

569 F. Supp. at 1295-96; 758 F.2d at 233; Keeten, 578 F. Supp. at

1174.

6

SUMMARY:

This is the earliest study on the conviction proneness

of death-qualified jurors. The data for the study were collected

by Professor Zeisel and his late colleague Professor Harry Kalven,

Jr. in 1954- and 1955, although the present monograph was not published

until 1968. (In Witherspoon, the Supreme Court had before it some

fragments of an early draft of this study; see 391 U.S. at 517

n.10). One distinctive feature of this study is that it examined

the behavior of actual criminal trial jurors. The researchers

interviewed jurors who had just completed service on felony trial

juries in the Brooklyn Criminal Court in New York and in the Chicago

Criminal Court in Illinois, and asked them three questions: (i) What

was the first ballot vote of the jury as a whole? (ii) What was your

own first ballot vote? (iii) Do you have conscientious scruples

against the death penalty? In all, the researchers collected data

on 464 such votes. Professor Zeisel analyzed these data, controlling

for the strength of the evidence of the defendant's guilt, and deter

mined what subjects with scruples against the death penalty voted to

acquit significantly more often then those without scruples against

the death penalty.

2. WILSON, 1964

AUTHOR: WILSON, W. Cody

TITLE: "Belief in Capital Punishment and Jury Performance,"

unpublished (1964).

CITATIONS: Hovey, 28 Cal.3d at 32-33, 43; 616 P .2d at 1318-19, 1327;

Grigsby, 569 F. Supp. at 1295; 758 F .2d at 233-34; Keeten, 578 F. Supp.

at 1174.

SUMMARY:

Wilson, 1964 was the first experimental study on the

conviction-proneness of death-qualified jurors. The subjects --

7

187 college students -- were presented in 1964- with written

descriptions of five capital cases (four with a single defendant,

one with two codefendants), asked to assume that they were members

of the juries trying the cases, and requested to reach a decision

on each defendant's guilt or innocence. Each subject was also

asked "Do you have conscientious scruples against the death penalty,

or capital punishment for a crime?" Wilson found that subjects

without scruples against the death penalty voted for conviction

more often than those who had scruples against the death penalty

(difference significant at the p<.02 level).

3. GOLDBERG, 1970

AUTHOR: GOLDBERG, Faye (Faye Girsh)

TITLE: "Toward Expansion of Witherspoon: Capital Scruples Jury

Bias, and the Use of Psychological Data to Raise Presumptions in

the Law," 5 Harv. C.R.-C.L.L. Rev. 53 (1970).

CITATIONS: Hovey, 28 Cal.3d at 30-31; 516 P .2d at 1317-18; Grigsby,

569 F. Supp. at 1295; 758 F .2d at 233; Keeten, 578 F. Supp. at 1174.

SUMMARY:

The subjects in this 1966 study — 200 students in private

liberal arts colleges in Georgia, 100 white and 100 black — were

given 16 written descriptions of criminal cases involving various

crimes, and were asked to assume that they were jurors and to

indicate their vote on the case. They were also asked: "Do you

have conscientious scruples against the use of the death penalty?"

Subjects without scruples against the death penalty voted to convict

in 75% of the cases, while those with scruples voted to convict in

69% (difference significant at the p<.08 level).

8

JUROW, 1971

AUTHOR: JUROW, George L.

TITLE: "New Data on the Effects of a 'Death-Qualified' Jury on

the Guilt Determination Process," 84 Harv. L. Rev. 567 (1971).

CITATIONS: Hovey, 28 Cal.3d at 33-36; 616 P .2d at 1319-21; Grigsby,

569 F. Supp. at 1296-97; 758 F .2d at 234; Keeten, 578 F. Supp. at

1174.

SUMMARY:

Jurow's subjects — 211 employees of the Sperry Rand

Corporation in New York — listened to two tape recordings of

simulated murder trials including, in abbreviated form, opening

statements, examination of witnesses, closing arguments, and the

judge's instruction to the jury, and voted on the guilt or innocence

of the defendant by marking a ballot. In addition, Jurow asked his

subjects to complete a long questionnaire that contained several sets

of questions relating to the death penalty, one of which (a five-point

scale designated "CPAQ(B)") included a statement embodying the first

prong of the Witherspoon criteria for exclusion: "I could never vote

for the death penalty regardless of the facts and circumstances of the

case." When the subjects are divided into groups on the basis of their

positions on that five-point CPAQ(B) scale, the pattern that emerges

resembles the patterns of responses to Bronson's attitudinal surveys:

the subjects who more strongly favor the death penalty are more

likely to convict. These differences are statistically significant

at the .01 level in Jurow's first case, but not statistically significant

in the second.

5. HARRIS, 1971

AUTHOR: LOUIS HARRIS & ASSOCIATES, INC.

TITLE: Study No. 2016

9

CITATIONS: Hovey, 28 Cal.3d at 36-37, 616 P .2d at 1321-23; Grigsby,

569 F. Supp. at 1297-98; Keeten, 578 F. Supp. at 1173-74.

SUMMARY:

The Harris, 1971 study, in addition to its attitudinal

and demographic data (see supra pp. 3-4) gathered behavioral data

on conviction-proneness. Each of the 2,068 subjects in the national

sample was instructed about three legal principles which apply to all