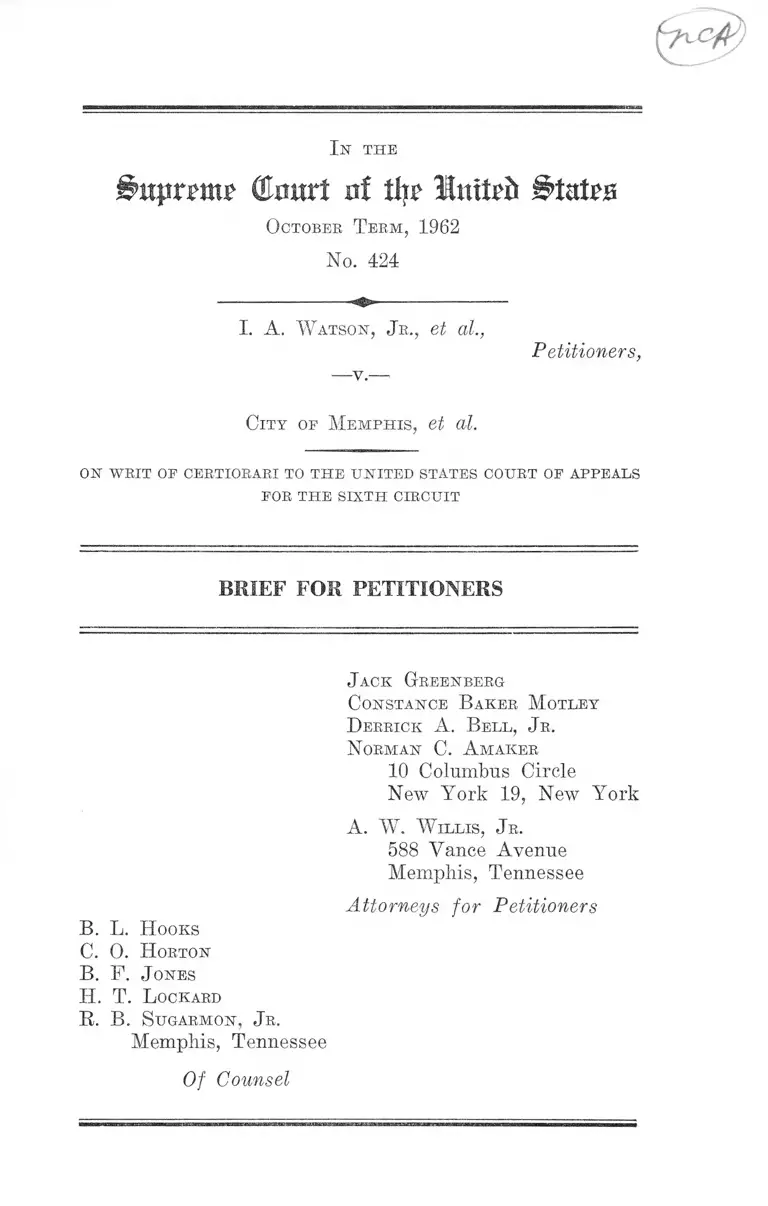

Watson v. City of Memphis Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Watson v. City of Memphis Brief for Petitioners, 1962. 5634fec1-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9c469198-475b-4a3e-bd84-3ece755f654f/watson-v-city-of-memphis-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

)

I n the

(Erntrl nf tltr H&nxtvb BtnUs

O ctober T er m , 1962

No. 424

I. A. W atson , J r ., et al.,

Petitioners,

C it y of M e m p h is , et al.

o n w r i t o f c e r t i o r a r i t o t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s c o u r t o f a p p e a l s

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

Constance B aker M otley

D errick A. B ell , Jr.

N orman C. A m aker

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

A. W. W il l is , Jr.

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

B. L. H ooks

C. 0. H orton

B. F . J ones

H . T . L ockard

R. B. S ugarm on , J r .

Memphis, Tennessee

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below ............................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .............. 1

Questions Presented ........................................................ 2

Constitutional Provision Involved ................................. 2

Statement ................... 3

Argument ............................ 7

I. Constitutional Eights Should Be Enforced

Immediately. To this Established Eule the

Second Brown Decision Is a Narrow Excep

tion Which Was Never Intended to Cover

Anything But Public Elementary and Sec

ondary Schools .................... 7

II. Irrespective of Whether the Second Brown

Decision Has Any Applicability Beyond the

Area of Elementary and Secondary Schools,

It Does Not Apply to Public Eecreational

Facilities .............. 10

III. Assuming That in Some Cases the Principles

of the Second Brown Decision May Be Ap

plied to Delajr Desegregation of Public Eecre

ational Facilities, This Eecord Presents No

Considerations Which Justify Delay ......... 12

C oxclttsion 22

11

T able of C ases

page

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark.

1959), aff’d sub nom. Faubns v. United States, 361

U. S. 197.................................................... ................... 16

Booker v. Tennessee Board of Education, 240 F. 2d

689 (6th Cir. 1957) .......... ..................... ................ ...... 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ....8,10

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) ....2, 6, 7,

8,9

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) ............... ...... 15

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 (1961) .................................................................... 17

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp. 42

(E. D. La. 1960), aff’d 365 U. S. 569; 188 F. Supp.

916 (E. D. La. 1960), aff’d 365 U. S. 569 .................. 16

City of Fort Lauderdale v. Moorhead, 152 F. Supp. 131

(S. D. Fla.), aff’d 248 F. 2d 544 (5th Cir. 1957) ...... 17

City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F. 2d 830 (5th

Cir. 1956), cert, den., 353 U. S. 922 (1957) .............. 16

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio, 228

F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956) ........................ ................... 22

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) .......................... 19

Cummings v. City of Charleston, 288 F. 2d 817 (4th

Cir. 1961) ........... ........ ....... .......................................... 7>9

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220

F. 2d 386 (1955), aff’d 350 U. S. 877 ......................... 9

Department of Conservation and Development v. Tate,

231 F. 2d 615 (4th Cir. 1956), cert, den., 352 U. S.

838 (1956) .......... ................................................. ....... 16

PAGE

Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F. 2d 180

(6th Cir. 1955) ............................................................... 7, 9

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 347 U. S.

971; 350 U. S. 413 ........... ............... ............................ 9

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 ..................................... 8

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Snpp.

649 (E. D. La. 1961), aff’d 368 IT. S. 515 (1962) ........ 16

James v. Almond, 170 F. Snpp. 331 (E, D. Va. 1959),

app. dismissed, 359 IT. S. 1006 ..................................... 16

M'cLanrin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 .... 7

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350

U. S. 877 ........................................................................ 9

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n, 347 IT. S. 971 20

Pennsylvania v. Board of City Trusts of Philadelphia,

353 U. S. 230 (1957) .................... ............................... 17

Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma,

332 U. S. 631 .............. ................................................ 7

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ..................................... 7

ill

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 (1962) 15,19

IV

S tatutes and Oth er A uthorities

page

Constitution of the United States, Fourteenth Amend

ment, Section One ....................................................... 2

United States Code, Title 28, §1254(1) ..... 1

United States Code, Title 28, §1343(3) ........ 3

United States Code, Title 28, §§2201, 2202 ...... 3

United States Code, Title 42, §§1981, 1983 ..... 3

Southern School News (December 1962) ..................... 10

I n th e

(Hxmvt uf tlj? 3lnit^ States

O otobeb T eem , 1962

No. 424

I. A. W atson , Jb., et al.,

Petitioners,

Cit y oe M e m p h is , et al.

ON W BIT OP CEBTIOBABI TO THE UNITED STATES COUBT OE APPEALS

EOB THE SIXTH CIECUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The district court rendered an unreported oral opinion

(R. 105). Its judgment (R. 102-04) was filed June 20, 1961.

Its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (R. 91-101),

filed on June 27, 1961, are unreported. The opinion of the

Court of Appeals (R. 111-122) is reported at 303 F. 2d 863.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered June

12, 1962 (R. 110). The petition for writ of certiorari was

filed September 10, 1962, and was granted November 19,

1962 (R. 123). The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28

U.S.C. 1254(1).

2

Questions Presented

Petitioners sued to enjoin the continued operation of the

Memphis park system on a racially discriminatory basis.

Relying on the decision in Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U. S. 294 (1955), the district court denied the injunction

and accepted respondents’ plan to desegregate gradually

over a period of years. The Court of Appeals affirmed on

the same ground.

Do the principles stated in the second Brown opinion,

which allow public school authorities to proceed toward de

segregation “with all deliberate speed” :

1. Have any application beyond the field of public edu

cation?

2. Apply to the field of public recreation ?

3. If applicable to public recreation, justify continued

segregation absent a showing of serious administrative im

pediments to desegregation?

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Section One of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

3

Statement

On May 13, 1960, petitioners for themselves and other

Negro citizens residing in Memphis, filed suit in the United

States District Court for the Western District of Tennessee,

Western Division, for a declaratory judgment and per

manent injunction restraining the Memphis Park Commis

sion and others from operating public recreational facilities

on a racially segregated basis. Jurisdiction was based on

28 U.S.C. §1343(3), 28 U.S.C. §§2201, 2202 and 42 U.S.C.

§§1981,1983.

In substance they complained that defendants main

tained some facilities exclusively for white and others ex

clusively for Negro citizens. Petitioners further alleged

that they and other members of the class attempted to use

facilities restricted to white persons and were barred or ar

rested on account of race or color contrary to the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and 42

U.S.C. §1981 (R. 2).

July 1, 1960, defendants answered (R. 8-12). The answer

did not deny operating segregated recreational facilities.

Rather, defendants asserted in justification: that facilities

for Negroes were equal to those for whites; that Memphis

provided a system of neighborhood parks designated for

whites or Negroes according to the racial make-up of the

area and that “ [i]n other than residential areas, the parks

are used generally by all the citizens of Memphis” (R. 9) ;a

that certain lands upon which recreational facilities were

situated were acquired under restrictive conditions relating 1

1 Evidence, however, showed that the neighborhood policy was

not uniformly adhered to in that in some previously white neigh

borhoods which became predominantly Negro, the parks or play

grounds were still maintained exclusively for whites (R. 78). More

over, at least one city-wide facility, Crump Stadium, was still

operated on a segregated basis (R. 79).

4

to use solely by white persons; that “problems” in the na

ture of “ riots, violence, and disharmony” (B. 10, 11) would

be the likely consequence of immediate court-ordered de

segregation of all facilities and, therefore, these defendants

in discharge of their duties as public officers and in exercise

of their police power felt it necessary to maintain the sys

tem as constituted; that a loss of revenue would result

from a loss of attendance caused by fear of disorders; that

the expense of operating the parks would be prohibitive

because of the extra police protection required, since “ the

incidence of violence, vandalism and disorders among vis

itors to the parks of the City of Memphis is greatly in

creased in those parks frequented by Negro citizens of the

City of Memphis” (R. 12).

The cause came on for trial June 14-15, 1961. The facts

were established substantially as plaintiffs alleged: The

City of Memphis, through its Park Commission, operated

and maintained a public recreational system of 108 parks2

on city-owned land. Fifty-eight of the parks were re

served for the exclusive use of white persons, 25 were for

Negroes, and 25 were partially or wholly integrated.3 The

facilities reserved for whites included 40 neighborhood play

grounds, 8 community centers, 5 golf courses and 5 swim

ming pools (R. 93). Negroes who attempted to use “white”

facilities were denied admission, and in some eases were

arrested if they refused to leave when ordered (R. 25,

74-77). Reserved for Negroes were 21 neighborhood play

2 In addition, the Park Commission operated 56 playgrounds and

facilities on property owned by various churches; 30 designated as

“white,” the rest restricted to Negroes (R. 70).

3 A t at least one of these facilities, however, racial bars had not

been completely removed; the toilet facilities at Overton Park Zoo

were still segregated at the time of trial (R. 83). Testimony also

revealed that at one of the older “integrated” facilities, Court

Square, there were toilets for whites only (R. 75).

5

grounds, 4 community centers, 5 swimming pools, and 2

golf courses (R. 93).

The Park Commission’s policy was to open up parks

from time to time for all citizens (R. 39). It had recently

removed racial restrictions at three “ city-wide” facilities

as part of its gradual desegregation plan (R. 40), and other

facilities throughout the city were scheduled to be deseg

regated on a gradual basis in accordance with that plan

(R. 41). Commission officials and the local chief of police

testified that, in their opinion, any desegregation in public

recreational facilities taking place in any manner other

than that proposed by the Commission’s gradual plan would

produce turmoil, confusion, and perhaps bloodshed in the

City of Memphis (R. 42, 48, 53, 88), although there had

not been any violence in the past due to the integration of

facilities nor had any “agitators” appeared (R. 53, 81).

The belief that immediate integration of all facilities would

lead to violence was based on anonymous letters and phone

calls that were received when facilities had been integrated

in the past (R. 53). They further testified that Memphis,

having been “singularly blessed by the absence of turmoil

up to this time,” the Park Commission desired to make all

City-wide facilities available to Negroes “with all deliberate

speed” (R. 43).

There was evidence relating to an art gallery and museum

known as the “Pink Palace” in support of defendants’

assertion that certain lands upon which public recreational

facilities had been built had been acquired through deeds

containing racially restrictive covenants. It was urged,

therefore, that complete integration should await construc

tion of these deeds by the Tennessee courts (R. 39).4

4 However, the Pink Palace Museum had been opened for Negro

use one day per week (R. 50) without objection from the corporate

grantor or its successors (R. 50, 51).

6

On June 20, 1961, the District Court, the Honorable

Marion Speed Boyd presiding, entered judgment denying

petitioners’ application for permanent injunction as prayed

in the complaint, approving the Park Commission’s gradual

plan (R. 102-104), requiring defendants to submit a further

plan with respect to integration of playgrounds and com

munity centers within a period of six months,5 and staying

decision with reference to the Pink Palace Museum until

the Chancery Court of Shelby County, Tennessee, had an

opportunity to determine the effect of integration of the

races upon the title to this property (R. 103). The Court

in its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (R. 91-101)

found that because of the local conditions in Memphis,

additional time was needed to accomplish full desegrega

tion of the public recreational facilities and that the gradual

plan was in the public interest and was “ consistent with

good faith implementation of the governing constitutional

principles as announced in Brown v. Board of Education

[349 U. S. 294 (1955)]” (R. 101).

Petitioners on July 7, 1961, appealed to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. On June 12, 1962,

that Court affirmed the judgment of the District Court on

the Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law of the Dis

trict Judge. The Court of Appeals stated that the sole

issue tendered by petitioners on their appeal was whether

the allowance of any delay in total desegregation of all

Memphis recreational facilities deprived them of their con

stitutional rights, i.e., whether the decision in the second

Brown case applied to public recreational facilities as well

as to public schools. In deciding this issue, the Court said:

5 Under the provisions of this plan, which was submitted on oral

argument in the Court of Appeals at that Court’s request, complete

integration of all facilities would not occur until 1971. The plan,

however, was not made part of the record.

7

We are of the view that the principle stated in

Brown v. Board of Education, supra, relating to the

desegregation of schools, is applicable to the present

case, involving the desegregation of recreational facil

ities of the City of Memphis. In our opinion the

Brown decision is not limited to cases involving pub

lic schools, as is here contended by appellants. Detroit

Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F. 2d 180, 184,

185 (C. A. 6); see also Cummings v. City of Charleston,

288 F. 2d 817 (C. A. 4) (R. 120).

A R G U M E N T

I.

Constitutional Rights Should Be Enforced Immedi

ately. To This Established Rule the Second Brown Deci

sion Is a Narrrow Exception Which Was Never Intended

to Cover Anything But Public Elementary and Secondary

Schools.

There can he no question that the Fourteenth Amend

ment entitles petitioners to the nondiscriminatory use of

all parks and recreational facilities operated by the City

of Memphis. At issue here is whether any justification

exists for prolonged abridgement of these rights. Peti

tioners find none and contend that the desegregation of

these public recreational facilities must be effected im

mediately.

Constitutional rights are personal and present. This set

tled principle, which means that the enforcement of recog

nized constitutional rights cannot be put off until some

future time, has often been invoked by this Court in cases

closely analogous to this one. See McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Begents, 339 U. S. 637, 642; Sweatt v. Painter, 339

U. S. 629, 635; Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University

8

of Oklahoma, 332 II. S. 631, 632-33. The logic of the rule

is demonstrated by the paradox that would ensue if this

case were affirmed: thousands of Negroes in Memphis

would be denied admission to scores of city parks for sev

eral years although the right of which they demand im

mediate exercise has been recognized—in the abstract—by

the highest court in the land.

The courts below have held that the second Brown deci

sion, Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955),

controls this case and permits lengthy delay in the full im

plementation of petitioners’ admitted constitutional rights.

Petitioners disagree, for that decision can have no applica

tion to any area other than public schools.

A fundamental distinction exists between the decision of

May 17, 1954, and that of May 31, 1955. In the former,

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. 8. 483, this Court

was acting in its role as expositor of the Constitution,

and it declared that segregated educational facilities,

being inherently unequal, constituted a denial of the equal

protection of the laws. Since 1954, this principle has prop

erly been extended, by this Court and by the lower courts,

to every aspect of public activity. However, in 1955, this

Court was exercising its function as a court of equity,

which must deal with the circumstances of the particular

case when framing a specific decree. Recognizing that the

“ solution of varied local school problems” could best be ef

fected by the district courts, this Court remanded each of

the consolidated cases for detailed treatment by the respec

tive district courts. This remedial determination stemmed

from an examination of the peculiar difficulties arising from

the alteration of complex public school systems, and has no

relevance whatever to other areas in which segregation has

been enforced.6

. 6 See, e.g., Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 (public transporta

tion) : “The motion to affirm is granted and the judgment is af

firmed. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 . . . ” It is to

be noted that the 1955 opinion was not cited.

9

The narrow compass of the 1955 decision was demon

strated the following year wdien this Court ordered the im

mediate admission of a Negro applicant to graduate school.

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 350 U . S. 413

(1956). On May 24, 1954, the Supreme Court had issued

a mandate to the Supreme Court of Florida directing that

the case be reconsidered in light of the decision of 1954

“ and conditions that now prevail.” Florida ex rel. Hawkins

v. Board of Control, 347 U. S. 971. Following the Florida

Supreme Court’s subsequent refusal to grant the Negro im

mediate relief, this Court held that its previous decision

“did not imply that decrees involving graduate study pre

sent the problems of public elementary and secondary

schools.” 350 U. S. at 413. See also Booker v. Tennessee

Board of Education, 240 F. 2d 689 (6th Cir. 1957). It is

also significant that in Dawson v. Mayor and City Council

of Baltimore, 220 F. 2d 386 (1955), aff’d, 350 U. S. 877

(1955), this Court affirmed the Fourth Circuit’s ruling

without opinion, despite the City’s insistence7 that the

second opinion in Brown should apply.8

Apart from precedent, strong considerations of policy

suggest that the doctrine of the second Brown opinion

should be limited rather than extended. First, it is an

anomaly in the law that personal rights—especially rights

so highly valued as those protected by the equal protection

7 Jurisdictional Statement, p. 19, Mayor and City Council of

Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877 (No. 232, Oct. Term 1955).

8 Contrary to the conclusion of the court below, the lower courts

have not countenanced delay in areas other than schools. In De

troit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F. 2d 180 (1955), the Sixth

Circuit upheld a district court order requiring immediate assim

ilation of separate waiting lists for Negro and white housing

projects. While the relief given could not assure the immediate

achievement of nonsegregated occupancy, it effected all that could

possibly be done in the situation. In Cummings v. City of Charles

ton, 288 F. 2d 817 (4th Cir. 1961) (municipal golf course), the

plaintiffs received all the relief they requested.

10

clause—should not be enforced forthwith. Second, around

the “all deliberate speed” formula has grown a mass of

litigation which, because of its complexity, severely burdens

the lower courts. Finally, after nine years of experience

with the “all deliberate speed” doctrine, 92.2% of the Negro

school children in 17 states and the District of Columbia

attend schools with no white students.9 This is the result,

on the one hand, of widespread disregard of the great prin

ciple established in 1954, and on the other hand, of the

tremendous burden which the 1955 decree imposes on those

who must look to the courts for enforcement of their rights.

II.

Irrespective of Whether the Second Brown Decision

Has Any Applicability Beyond the Area of Elementary

and Secondary Schools, It Does Not Apply to Public

Recreational Facilities.

In the School Segregation Cases, this Court was dealing

with the problem of transforming totally segregated

systems of public elementary and high schools into systems

providing full equality through the elimination of segrega

tion. Involved in such a transformation, as the Court

recognized, were taxing problems of an administrative

nature, particularly those

arising from the physical condition of the school plant,

the school transportation system, personnel, revision

of school districts and attendance areas into compact

units to achieve a system of determining admission to

the public schools on a nonracial basis and revision

9 Between 1961 and 1962 the percentage of Negro children in

schools with white students increased from 7.6 to 7.8. See Southern

School News, p. 1, published by the Southern Education Reporting

Service (December 1962).

11

of local laws and regulations which may he necessary

in solving the foregoing problems (349 IT. S. at 300-01).

Clearly, the desegregation of a public recreational system

presents no such administrative difficulties as might arise

in public schools. Attendance at public parks is not compul

sory. Users of parks are not transported to them at public

expense. Persons need not be assigned to individual parks

or facilities. Whereas the overcrowding of schools presents

a serious obstacle to rapid desegregation, overcrowded

conditions in park facilities are automatically controlled

by factors of supply and demand; the first comers are

served while the late comers wait their turn, find other

accommodations or do without the benefits of the facilities,

all at their own discretion. Becreational activities, being

less closely supervised, require fewer personnel than

schools. Local park authorities are bound by fewer and

less restrictive state regulations than school boards.

In sum, the administration of a park system is less com

plex. Effectuation of complete desegregation of public

parks requires little more than the removal of racial signs,

and an announcement that racial distinctions wfill no longer

be observed. In all other respects, the park system can

operate on a desegregated basis exactly as it does on a

segregated basis.10

_ 10 Pull integration of park personnel requires some administra

tive effort, but such relief is not requested in this case.

12

III.

Assuming That in Some Cases the Principles of the

Second Brown Decision May Be Applied to Delay De

segregation o f Public Recreational Facilities, This Rec

ord Presents No Considerations Which Justify Delay.

Petitioners maintain that the second Brown decision

sanctions delay in the public schools only, and that in any

event it does not permit continued segregation of public

recreational facilities. Assuming, however, that neither of

these arguments finds favor with this Court, it is submitted

that faithful application of the 1955 decision to the facts

established in this record requires an order directing im

mediate desegregation of the Memphis park system.

Petitioners proved at trial that the Memphis Park Com

mission operates a city-wide, public recreational system

on an almost wholly segregated basis (R. 92, Finding No.

V). It was further shown that several Negro citizens had

been denied admission to or ejected from various facilities

or arrested for refusing to leave, solely on the ground

of race. These facts were uncontested. Upon such a clear

showing of a violation of constitutional rights, normal

procedure for any court is to formulate a remedy which

will eliminate such denials forthwith. This the district

court did not do.

Justification for this departure from normal practice

was predicated on the Brown opinion of 1955. However, in

that case this Court did not give the lower courts carte

blanche to withhold relief in desegregation cases until the

administrative authorities deemed compliance with the gov

erning constitutional principles to be convenient or de

sirable. It merely declared that varying local conditions

13

may at times make immediate compliance impracticable,

and set forth a list of those administrative problems which

could be considered as justifiably prolonging the process

of complete obedience. The burden of presenting the case

for delay rests on the defendants who have violated the

Constitution, 349 U. S. at 300, and absent a showing of ad

ministrative impracticability, the district court’s duty to

order immediate desegregation remains.

By a parity of reasoning, if the doctrine of “ all deliberate

speed” is to be applied to recreational systems, delay cannot

be tolerated unless such administrative factors as those

listed in the second Brown decision are shown by the public

officials to require some hesitation in the complete vindica

tion of a complainant’s rights. Respondents in this case

utterly failed to carry the burden placed upon them. At

the trial, their witnesses made dire predictions about the

consequences of immediate integration, but examination of

each supposed problem reveals both the inadequacy of

proof presented and the irrelevance of the considerations

raised.

Confusion, Turmoil and Bloodshed

Time and again throughout the trial, respondents’ three

witnesses expressed the fear that confusion, turmoil,

violence and bloodshed would ensue if desegregation pro

ceeded rapidly (R. 42, 43, 47, 53-55, 57, 72, 73, 80-87, 87-90).

However, these oft-repeated convictions were supported

by almost no facts. One witness testified that he received

anonymous letters and telephone calls whenever a facility

was opened to both races (R. 53). Another mentioned that

policemen sometimes had to be called to control rowdyism

on the segregated playgrounds, more often on Negro play

grounds (R. 81). One reference was made to the fact that

additional police had been assigned to a recently desegre

14

gated zoo. Finally, one incident was mentioned in which

“ bloodshed and shootings and knifings” had occurred in

one Negro park (E. 83). No other evidence of previous

violence was produced, although racial bars had been

removed at twenty-five facilities by the time of trial.

On the other hand, the Chairman of the Park Commission

acknowledged that Memphis has been “ singularly blessed

by the absence of turmoil up to this time on the racial

question” (E. 43), and testified that no violence had erupted

at any of the integrated facilities (E. 53). Indeed, police

protection in the park system generally seems not to be

a very serious problem, since there are only fourteen men

on the city’s entire park police force (E. 84). It also

appeared from the testimony that the police have been

able to preserve order since buses in the city were desegre

gated (E. 87). The record refers to only one instance of

violent reaction to racial issues in the City of Memphis,

and in that incident, a sit-in demonstration, the police

observed the development of mob conflict for “ twenty or

thirty minutes” before taking action (E. 90).11

Assuming, however, that immediate desegregation of all

parks would pose a threat to the maintenance of law and

order, respondents still would not be relieved of the duty

to remove racial restrictions. This was settled for all time

in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958). If the conditions

existing in Little Eock, to which the President was forced

to send federal troops, could not excuse postponement of

11 Respondents’ witnesses attempted to make much of Memphis’

“peculiar location” in the southwest corner of Tennessee, bordering

on heavily Negro counties of Mississippi and Arkansas (R. 47-48,

53-55, 90). Apparently it is feared that immediate and total inte

gration would cause a massive influx of outside Negroes into Mem

phis’ parks and promote racial agitation by members of both races.

Like respondents’ other evidence on the issue of violence, this is

irrelevant speculation.

15

school desegregation, certainly a city “ singularly blessed

by the absence of racial turmoil” cannot continue its dis

criminatory policies in the name of maintaining law and

order. As this Court held, “ [L]aw and order are not here

to be preserved by depriving the Negro children of their

constitutional rights,” 358 U. S. at 16. The case of Buchanan

v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 81 (1917), established the same

principle over forty-five years ago: “ [Ijmportant as is the

preservation of the public peace, this aim cannot be accom

plished by laws or ordinances which deny rights created

or protected by the Federal Constitution.” Cf. Taylor v.

Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 (1962).

Closing of Facilities

Related to the claim that violence would flare up if

immediate desegregation were ordered is respondents’ con

tention that many facilities would have to be closed because

insufficient personnel would be available to provide police

protection at all parks (R. 41, 61, 64, 73, 85-86). This

contention rests precariously on the premise that violence

would constitute a serious problem. As was observed above,

precious little evidence justifies concern on this score.

Furthermore, the existing pattern of residential segrega

tion (R. 67) substantially reduces the chance that neighbor

hood playgrounds, which comprise a major portion of the

park system, will experience much actual desegregation

even when official restrictions are removed.

On the other hand, in the unlikely event that respondents’

fears of widespread public disturbance are vindicated,

ample police protection is available even in the most ex

treme situations from state and federal law enforcement

agencies. Given the capacity of law enforcement officials to

maintain order, the courts should not be deterred from

16

enforcing constitutional rights by defiant threats to close

public facilities. Cf. City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, 238

F. 2d 830, 832 (5th Cir. 1956), cert, denied, 353 U. S. 922.

Indeed, in numerous school cases segregation has been en

joined in the face of closing laws and enforcement of the

closing laws has been enjoined as well. James v. Almond,

170 F. Supp. 331 (E. D. Va. 1959), app. dismissed, 359 U. S.

1006; Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark.

1959), aff’d sub nom. Faubus v. United States, 361 U. S.

197; Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp.

42 (E. D. La. 1960), aff’d, 365 IT. S. 569; Id., 188 F. Supp.

916 (E. D. La. 1960), aff’d, 365 IT. S. 569; Hall v. St. Helena

Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp. 649 (E. D. La. 1961),

aff’d, 368 U. S. 515 (1962).

Econom ic Loss

The second most important factor (R. 57) motivating

respondents to proceed slowly was the possibility of reve

nue losses resulting from a predicted decline in attendance

at integrated facilities (R. 48, 57-58, 84-85). The only fact

mentioned in this connection was that three-quarters of a

million dollars is collected annually from revenue-producing

facilities. Comparative rates of attendance at segregated

and nonsegregated parks were not given. No evidence of

decreasing attendance at integrated facilities was offered.

This claim is entirely bereft of evidentiary support.

However, respondents’ failure to show that integration

would cause economic loss is of little consequence. The City

of Memphis and its Park Commission, as instrumentalities

of the State of Tennessee, should not be allowed to profit

from a system based on racial segregation. The lower

courts have decided this point often. See Department of

Conservation and Development v. Tate, 231 F. 2d 615

(4th Cir. 1956), cert, denied, 352 U. S. 838 (1956); City

17

of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F. 2d 830 (5th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied, 353 U. 8. 922 (1957); City of Fort Lauderdale

v. Moorhead, 152 F. Supp. 131 (S. D. Fla.), aff’d 248 F. 2d

544 (5th Cir. 1957). Cf. also Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U. S. 715, 724 (1961).12

Loss of Title to City Properties Burdened With

Restrictive Covenants

Another consideration purporting to stand in the way of

immediate desegregation relates to those facilities, partic

ularly the Pink Palace Museum, located on lands conveyed

to the city through deeds containing racially restrictive

clauses (R. 33-37, 50-52, 59-60). The city argued that the

federal courts should abstain from ordering desegregation

until the state courts had determined whether title to such

properties would revert to the grantors if the covenants or

conditions were breached. To that end, the district court

ordered the city to seek an adjudication in the state courts

(R. 103, 108). This was plain error, for whatever the out

come of that litigation, the city may not continue to operate

these facilities on a segregated basis. See Pennsylvania v.

Board of City Trusts of Philadelphia, 353 U. S. 230 (1957).

This property litigation may be a long and arduous process,

during which Negroes should not be forced to endure dis

crimination.

This is particularly true where, as here, constitutional

rights are being denied on a mere speculation that the

12 rpjjg reSp011(j entg were also solicitous of the vested interest in

segregation held by private concessionaires who operate under con

tract with the Park Commission and rely on high rates of at

tendance (R. 42, 65, 66, 83, 84). Again there was no proof of a

genuine threat to the concessionaires’ interests. Moreover, if this

claim could be substantiated, Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, supra, which required the lessee to admit Negroes, more

than establishes the Commission’s duty to desegregate where it

retains control of policy in the parks.

18

grantor may assert his supposed rights under the racial

restriction. The deed in question provided that the racial

restriction could be enforced by the grantor only after he

had given a written notice and a further ninety-day period

of continued violation had elapsed (R. 36). It is extremely

doubtful that a corporate grantor would attempt to enforce

such a racial condition where its breach was occasioned by

obedience to an injunction. Indeed, at the time of trial,

the grantor had given no notice even though the restriction

was being violated to the extent of allowing Negroes to

use the Pink Palace on Tuesdays (R. 50-51).

Other Factors

The other considerations urged by respondents—that

Negro facilities were equal to those provided for whites,

that immediate desegregation would reduce good will be

tween the races, and that additional time was needed for

the citizens of Memphis to adjust to a changing social

structure—are equally inapposite. To the “ equal facilities”

argument (R. 44-46, 59, 63, 69, 71, 72, 78), the answer is

that 58 parks are reserved for white persons, 25 for

Negroes (R. 69, 92). Regardless of the proportion of

Memphis’ population which Negroes comprise (35% (R.

47)), those 25 facilities are necessarily more widely

scattered throughout the city than the 58 white facilities,

and thus are less accessible. Indeed it is questionable

whether separate recreational facilities in a city of 500,000

can ever be equal, even when judged solely by tangible

factors. When less tangible factors are considered, it be

comes relevant that the conceded right of petitioners to

freedom from segregation is grounded on the premise that

separate facilities are inherently unequal. Liberation of

the Negro school child from feelings of racial inferiority

cannot be achieved by relegating him to a segregated play

ground after school hours.

19

The contention that existing good will between the races

would suffer if the Negro petitioners’ rights were vindicated

immediately is spurious (R. 88). If contingent upon con

tinued subjection of one race to a position of inferiority,

this communal bond is hardly worthy of preservation; if

it is not so conditioned, integration will cause no problem.

At any rate, Cooper v. Aaron, supra, demonstrates that

even extreme racial tension cannot prevent the enforce

ment of Fourteenth Amendment rights.

Additionally, it was pleaded that respondents be given

the time that gradual desegregation would provide for

the citizens of Memphis to adjust to new conditions (R. 72,

89). Except for references to problems of police protec

tion (but see Cooper v. Aaron, supra; Taylor v. Louisiana,

supra), respondents offered no proof that gradual adjust

ment, which prolongs any possible period of disquiet,

should cause less pain than immediate adjustment. A fair

reading of this record compels the conclusion that the

Commission was simply hesitant to move ahead of com

munity acceptance of this Court’s decisions. As this Court

held in the Brown case, “ the vitality of these constitutional

principles cannot be allowed to yield simply because of dis

agreement with them.” 349 U. S. at 300.

The various contentions raised by respondents reveal a

fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the prob

lems which this Court contemplated as justifying some

delay in public school desegregation. Obviously this Court

did not mean that constitutional rights could be deprived

indefinitely or whenever delay would make the transition

easier. Rather, as the list of administrative problems set

out in the Brown opinion implies, delay is only tolerable

when additional time is needed for the responsible author

ities to formulate solutions to bona fide administrative

difficulties, or, to a lesser extent, to carry into execution

complex administrative procedures. Without exception,

20

respondents in this ease failed to explain to the district

court how additional time might be used constructively to

devise administrative procedures for the solution of their

supposed problems. Bather they urged that the problems

would disappear if only sufficient time were given for

desegregation to be effected gradually. Both the letter and

spirit of the 1955 decision command more diligent effort.18

Finally, respondents urged that they had shown good

faith. This they claimed with an apparent sincerity14 which

the facts do not bear out. Although this Court established

that segregated parks violate the Fourteenth Amendment

in 1954 (Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n, 347 U. S.

971), several new parks and facilities have been opened on

a segregated basis in Memphis since that time (R. 31, 52;

14, 102). What better opportunity to effectuate of sincere

policy of gradual desegregation than to admit all citizens as

each new park is opened? What better way to solidify a

segregated system than to segregate new facilities? The

city claimed that all “ city-wide” facilities have been opened

to both races, but the record shows that Crump Stadium was

not open to Negroes (R. 79). It was contended that Court

Square had been desegregated, yet there were no rest rooms

for Negroes (R. 75). Contrary to announced policy, some

neighborhood playgrounds in predominantly Negro neigh

borhoods were still reserved for whites (R. 78-79). And,

against the protestation that twenty-five facilities had been

desegregated must be placed the fact that Negroes were not 13 14 * * *

13 Typical of respondents’ approach was the treatment of the

proposition that “extra supervisors and employees” would be needed

in newly integrated facilities (R. 47). Having predicted this need,

the Chairman of the Commission failed to explain why such person

nel would be needed, how the Commission proposed to meet this

supposed need, or why time would be necessary to work out a

solution.

14 The Chairman of the Park Commission stated that he would

“abide by the rules of this court or get off the Park Commission,

because I want no incidents here like they have had in other parts

of the south” (R. 53).

21

adequately informed of their right to attend newly deseg

regated facilities. The testimony of H. S. Lewis, Director

of Parks, concerning the recent desegregation of one facility

is enlightening:

Q. “Was there any publicity given to the fact that it

had been integrated?” A. “ No.”

Q. “Was there any way that Negroes could know that

they had a right to use Court Square?” A. “ Except

they used it and were not chased.”

Q. “ I say if the police do not put them out of a

particular park then they are free to use it?” A. “ Cer

tainly.”

Q. “They would not know, according to your testi

mony, whether they are free to use it until the police

asked them to get out?” A. “ That could be.”

Q. “Have Negroes been advised of their right to use

Confederate Park?” A. “ They have used it. Whether

they have been advised or not is a good question” (R.

75-76).

Judged in the light of these facts, the Commission can

hardly assert that good faith, in the ordinary meaning of

the term, has been shown. Much less has it shown “good

faith compliance at the earliest practicable date” or “good

faith implementation of the governing constitutional prin

ciples.” The case it put before the district court displays

its apparent inability even to understand those principles.

The district court in this case, although finding that

Memphis’ recreational system is operated on a racially dis

criminatory basis, refused to grant either injunctive or

declaratory relief, approved a tentative plan to open eight

facilities over a period of two and a half years, granted

respondents six months in which to file a complete plan, and

refused to adjudicate the allowability of continued segrega

tion by state officials on land burdened by a racially re

22

strictive covenant (R. 102-04). As this brief has under

taken to demonstrate, the district court’s judgment rested

on a clearly erroneous conception of the meaning of the

Brown decision and of the evidence which a court should

consider. Its action constituted an abuse of discretion which

the Court of Appeals should have reversed. Clemons v.

Board of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio, 228 F. 2d 853 (6th

Cir. 1956); id. at 859 (Stewart, J., concurring). Fully con

sistent with this Court’s recognition of a District Court’s

competence to assess local conditions with which it is fa

miliar is the fundamental proposition that disregard of

overriding constitutional principles must not be tolerated.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G-reenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

D errick A. B e ll , Jr.

N orman C. A m aker

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

A. W. W illis , Jr.

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

B. L. H ooks

C. 0. H orton

B. F. J ones

H. T. L ockabd

R. B. SlTGARMON, Jr.

Memphis, Tennessee

Of Counsel