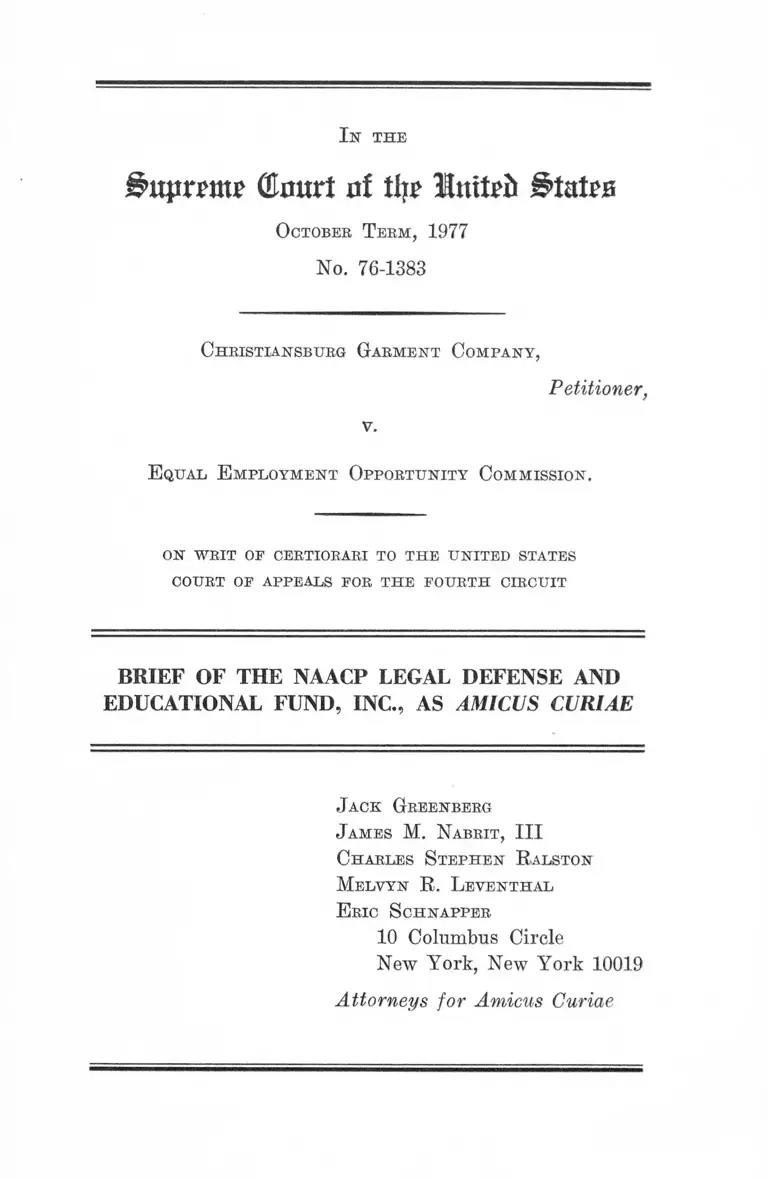

Christiansburg Garment Company v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Christiansburg Garment Company v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Brief Amicus Curiae, 1977. 1be83f80-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9cc588b5-1730-4887-87fd-91c4ef78efdc/christiansburg-garment-company-v-equal-employment-opportunity-commission-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

i ’upmn? (ftmtrt of % Inttefc States

October Term, 1977

No. 76-1383

Christiansburg Garment Company,

Petitioner,

v.

E qual E mployment Opportunity Commission.

on w rit op certiorari to th e united states

court op appeals for the fourth circuit

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

Melvyn R. Leventhal

E ric Schnapper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

INDEX

Page

Interest of Amicus 1

Summary of Argument 3

Argument. 4

I. An Award of Counsel fees to

Defendants in Cases Brought

the Civil Rights Act Is In

consistent with Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises. 4

II. A Different Standard for Award

of Counsel Fees to Plaintiffs

and Defendants Is Required By

the Policy Considerations Enun

ciated In the Civil Rights Acts

and Is Not Inconsistent With

the language of Title VII 12

Conclusion 21

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Albermarle

(1975)

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.405 2

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co.v. Wilderness

Society, 421 U.S. 240 (1975)

17,18

Bradley v.

Richmond

School Board of the City of

, 416 U.S. 696 (1974)

3,7,14

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Mach. Co.,

457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972)

11

Byram Concretanks, Inc. v. Warren Concrete

Products Co., 374 F.2d 649 (3rd Cir.1967)

16

- l i -

Page

Carrion v. Yeshiva University, 535 F.2d

722 (2d Cir. 1975)

13,19

Donaldson v. Pillsbury Co., 554 F.2d 825

(8th Cir. 1977)

11

Fleischmann v. Maier Brewing Co., 386 U.S.

714 (1967)

8

Ford v. United States Steel Corp,520 U.S.

1043 (5th Cir. 1975)

9

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971)

2,4,11

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

United States, U.S. , 52 L.Ed.2d

396 (1977)

11

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express Co.,

488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974)

7

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

491 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974)

9

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421

U.S. 454 (1975)

2,11

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411

U.S. 792 (1973)

2

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S.415 (1963) 6

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390

U.S. 400 (1968)

passim

Northcross v. Memphis Board of Education,

412 U.S. 427 (1973)

3,7,14

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 2

U.S. 542 (1971)

Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d 10,11

333 (10th Cir. 1975)

Robinson v. Lorrillard Corp., 444 F.2d 7

791 (4th Cir. 1971)

Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp., 9

508 F.2d 152 (3rd Cir. 1975)

Rosenfeld v. Southern Pacific Co., 519 7

F.2d 527 (9th Cir. 1975)

Sherrill v. J.P. Stevens & Co., 410 F.Supp. 9

770 (W.D.N.C. 1975)

United Air Lines v. Evans, U.S. , 11

52 L.Ed. 2d 571 (1977)

United States Steel Corp. v. United 13,19

States, 519 F.2d 359 (3rd Cir. 1975)

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 5,11

1159 (5th Cir. 1976)

Wright v. Stone Container Corp., 524 13

F.2d 1058 (8th Cir. 1975)

Other Authorities:

42 U.S.C. §1981 17,20,21

42 U.S.C. §1982 17

42 U.S.C. §1983 17

- n i -

Page

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k) 6

H. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 17

(1976)

110 Cong. Rec. 12722 (June 4, 1964) 6

122 Cong.Rec. H12161 (daily ed.Oct.1,1976) 21

122 Cong.Rec. H12162 (daily ed.Oct.1,1976) 20

122 Cong.Rec. H12165 (daily ed.Oct.1,1976) 17

122 Cong.Rec. S16491 (daily ed.Sept.23,1976) 20

S.Rep. No.94-1011, 94th Cong.2d Sess., 17,18

(1976)

20 U.S.C. §1617 7,17

-iv-

Page

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1977

No. 76-1383

CHRISTIANSBURG GARMENT COMPANY,

v.

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION

On Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest of Amicus*

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation, incorpo

rated under the laws of the State of New York

in 1939. It was formed to assist Negroes to

secure their constitutional rights by the prose

cution of lawsuits. Its charter declares that

its purposes include rendering legal aid and

gratuitously to Negroes suffering injustice by

*Letters of consent to the filing of this

Brief from counsel for the petitioner and the

respondent have been filed with the Clerk of the

Court.

2

reason of race who are unable, on account of

poverty, to employ legal counsel on their

own behalf. The charter was approved by a New

York Court, authorizing the organization to serve

as a legal aid soceity. the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF), is independent

of other organizations and is supported by

contributions from the public. For many years

its attorneys have represented parties in this

Court and the lower courts, and it has partici

pated as amicus curiae in this Court and other

courts, in cases involving many facets of the

law.

Attorneys for the Legal Defense Fund have

handled many cases involving Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 and discrimination in

employment generally.* In addition, the Fund has

been primarily responsible for the development of

the law regarding counsel fee awards under

the various Civil Rights Acts having represented

plaintiffs in the leading cases of Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968);

*E.G .. Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp. ,

400 U.S. 542 (1971); Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971); McDonnell Douglas v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973); Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency, 421 U.S. 454 (1975); Albemarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).

Northcross v. Memphis Board of Education, 412

U.S. 427 (1973); and Bradley v. School Board of

the City of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696 (1974).

As counsel for plaintiffs in civil rights cases

we have a direct interest in the resolution of

the question before the Court in this case.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

The award of counsel fees to prevailing

Title VII defendants as a matter of course would

have a chilling effect on the filing of com

plaints by plaintiffs, regardless of the merits

of their cases. Such a result is precluded

by this Court's decision in Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968), which held that

the purpose of the counsel fee provisions in the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 was to "encourage

individuals injured by racial discrimination to

seek judicial relief."

II.

Congress intended to encourage the bringing

of private lawsuits to enforce the provisions of

the 1964 civil rights act. On the other hand, it

sought to discourage frivolous and vexatious

litigation by allowing counsel fees to prevailing

defendants under those limited circums tances.

The counsel fee provision in Title VII must be

- 3 -

- 4 -

read in light of the intent of Congress as

expressed both in 1964 and in more recent civil

rights counsel fee enactments.

ARGUMENT

I.

An Award of Counsel Fees to Defendants

Tn~ Cases Brought Under the Civil Rights

Act Is Inconsistent with NewmatTv^

Piggie Park Enterprises.

The resolution of the issue raised by the

present case, whether prevailing defendants in

Title VII actions are to receive counsel fees on

the same basis as are prevailing plaintiffs, will

determine whether or not Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 remains as a viable

remedy for those on whose behalf it was passed.

Title VII involves complex and difficult issues,

particularly in cases that are brought as across-

the-board class actions challenging systemic

practices of employers. From the time of the

filing of the complaint to the completion of

trial, up to 5 years may be required because of

the difficult problems such litigation presents.

Thus, the plaintiffs must be prepared to analyze

in depth a variety of practices that may impinge

on employment opportunities, including tests,— ''

2 / See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co, 401 U.S.

424 (1971).

- 5 -

2/methods of promotions— and the like. Statisti

cal and computer analyses of data, the use of

expert witnesses to analyze information, to

testify concerning the validity of tests, and to

suggest alternative ways of organizing a work

force so as to remove obstacles to equal employ

ment opportunities are essential parts of litiga

tion.

Needless to say, the bringing and maintain

ing of such litigation involves substantial

resources not only in personnel but in funds.

Lawyers' fees and expenses, expert witness fees

and expenses, salaries of research analysts and

computer personnel, and other funds expended as

ordinary costs of litigation must be found. Such

resources are far beyond the reach of ordinary

Title VII plaintiffs, who are most likely blue

collar workers at the lowest rung in the salary

scale. Indeed,it is because of their pos it ion

economically that such workers have sought out

the aid of the courts to achieve equality of

opportunity for themselves and others similarly

situated. Even in class actions, groups of

workers rarely have the funds necessary to

carry out their s ide of the litigation with

2/ See, e.g. , Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530

F.2d 1159 (5th Cir. 1976).

out the assistance of organizations such as the

Legal Defense Fund. Thus, their own lawyers are

either on the staff of a civil rights organiza

tion, or are attorneys in private practice work

ing in cooperation with such organizations who

receive only a minimal fee (see, e.g., NAACP v.

Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963)), but who do have the

expectation of an eventual award of counsel fees

under 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k).

It was precisely these concerns - the burden

on privarte plaintiffs - that led Congress to

enact a counsel fee provision as part of Title

3/ .VII.— In Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

- 6 -

3 / Congress recognized at the time it passed

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that a significant

part of the burden of enforcing the Act would

fall on private plaintiffs. Although the legisla

tive history of the counsel fee provisions in

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is not lengthy, it

indicates that Congress' main concern was to

provide an incentive for plaintiffs to file

lawsuits to enforce the rights established by

the Act. Thus, concern was expressed over the

fact that private plaintiffs lacked resources to

bring and presecute the kind of actions that

would be necessary under the Act. The counsel

fee provisions were inserted for the specific

reason to provide fee shifting so that a success

ful plaintiff would be able to obtain his

counsel fees. See, 110 Cong. Rec. 12722 June 4,

1964).

7

390 U.S. 400 (1968), this Court held that the

Congressional purpose of encouraging private

enforcement of the national policy embodied in

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 required

that counsel fees be awarded to prevailing

plaintiffs as a matter of course. This rule has

subsequently been applied by this Court to

private actions brought to integrate schools

within the scope of 20 U.S.C. §1617 (Northcross

v. Memphis Board of Education, 412 U.S. 427

(1973); Bradley v. Board of Ed. of Richmond, 416

U.S.696 (1974)), and by the courts of appeals in

cases arising under Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (see, e.g . , Johnson v. Georgia

Highway Express Co., 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir.

1974)); Robinson v. Lorrillard Corp., 444

F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971); Rosenfeld v. Southern

Pacific Co. , 519 F.2d 527 (9th Cir. 1975)).

We urge that the award of counsel fees to

defendants as a matter of course is precluded by

this Court's decision in Newman and would be

clearly inconsistent with Congressional intent

in enacting the counsel fees provisions as

part of the various civil rights acts.

In the first place, it is obvious that

given the fact that Title VII plaintiffs usually

cannot afford to bear the costs of their own side

of litigation, it would be impossible for them to

bear the costs of the defendant's side as well.— ̂

This, however, is the result sought by the peti

tioner in the present case. The Court must keep

in mind that this case arises in a posture which

may not present this particular problem, since it

involves an agency of the federal government.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, of

course, does not have the economic problems faced

by private Title VII plaintiffs. However, the

arguments made by petitioner would apply with

equal force to cases brought by private plain

tiffs, and therefore the Court must decide the

issue in the light of the policy considerations

that led Congress to pass the attorneys' fees

provision to begin with as decided by Newman.

- 8 -

4/ Indeed, this Court has explained one of the

rationales for the prevailing American rule in

terms of the effect of routine fee-shifting

on poor litigants:

In support of the American rule, it

has been argued that since litigation

is at best uncertain one should not be

penalized for merely defending or

prosecuting a lawsuit, and that the

poor might be unjustly discouraged from

instituting actions to vindicate their

rights if the penalty for losing

included the fees of their opponents'

counsel. Fleischmann v. Maier Brewing

Co., 386 U.S. 714, 718 (1967).

9

The effect of the threat of paying counsel

fees to a defendant who prevails in a Title VII

action as a matter of course will necessarily

mean that many plaintiffs who may have valid

claims, or whose claims are substantial enough

to warrant full consideration by the courts, will

simply either not bring law suits or will so

restrict their law suits as to render enforcement

of the Act ineffective. Civil rights attorneys in

advising potential plaintiffs whether or not to

bring an action will have no choice but to warn

them that they may become personally liable for

the counsel fees and expenses of their adversar

ies even when those adversaries have enormous

5/r e s o u r c e s A n attorney could not in good

conscience permit plaintiffs of limited resources

to be driven to bankruptcy if they do not prevail.

These concerns are not speculative, but

arise from our experiences since 1965, the

effective date of Title VII, in handling hundreds

of Title VII actions against employers ranging

from the United States Steel Corporation to

5/ See e.g., Ford v. United States Steel Corp.,

520 U.S. 1043 (5th Cir. 1975); Rodgers v. United

States Steel Corp., 508 F.2d 152 (3rd Cir.

1975); Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491

F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974); Sherrill v. J.P.

Stevens & Co., 410 F.Supp. 770 (W.D.N.C. 1975).

10 -

smaller concerns, and from the largest industrial

unions down to small locals. The issue must be

viewed from the perspective of the plaintiff and

of plaintiff's counsel in light of the Newman

ruling that the purpose of the counsel fee

provision is to encourage litigation.

A plaintiff has no assurance that he will

prevail when he, or she, is deciding whether

to initiate litigation. His access to facts is

limited; typically, he only knows that he has not

gotten a job or promotion. The underlying facts

are in the possession of the prospective defen

dant and can only be obtained after discovery.— ̂

Even after the raw data has been obtained,

sophisticated analysis is required to determine

precisely in what ways employment practices deny

equal opportunity.

The law of Title VII has developed gradually

and has taken dramatic shifts from time to

time.— Thus, it is difficult for a plaintiff

6/ See, e.g., Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522

F.2d 333, 342-45 (10th Cir. 1975).

]_/ For example, only last term this Court held,

contrary to most courts of appeals, that senior

ity systems did not violate Title VII if they

simply perpetuated the effects of pre-Act discrim

ination in the absence of an intent to discrimi

nate. International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

11

to predict that a case will be won even if the

facts seem clear. Similarly, district court

judges themselves often err in deciding cases,

8 /requiring reversal by the appellate courts. '

If a court, after a full trial of the evidence

can make a mis-judgment, a plaintiff should not

be penalized if he assesses his case wrongly

before a complaint is ever filed.

Even though a plaintiff may have a valid

claim on the merits, he may lose becasuse of

9 /a procedural bar not easily foreseen.— Also

to be considered is the result if a plaintiff

prevails on some issues but not all. Are

counsel fees to be apportioned, so that those

7/ Cont1d.

United States, U.S. , 52 L.Ed.2d 396

(1977)).

87 See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971); Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Mach.

Co., 457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972); Watkins v.

Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159 (5th Cir. 1976);

Donaldson v. Pillsbury Co., 554 F.2d 825 (8th

Cir. 1977); Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522

F.2d 333 (10th Cir. 1975).

9] See, e.g. , Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency, 421 U.S. 454 (1975); United Air Lines

v. Evans, U.S. , 52 L.Ed.2d 571

(1977).

12

awardable to indigent plaintiffs are cancelled

out by those awardable to a corporate defendant?

To catalogue the difficulties facing a

prospective Title VII plaintiff and his counsel

in trying to foresee whether they will ultimately

be successful, is to demonstrate the destructive

effect of the rule argued for by petitioner

here. In short, the only purpose and effect a

rule awarding counsel fees to prevailing defen

dants as a matter of course would be to discour

age and chill the private enforcement of Title

VII. Such a result would be totally inconsistent

with Newman and, as will be shown below, with

Congressional policy.

II.

A Different Standard for Award of

Counsel Fees To Plaintiffs and Defen

dants Is Required By The Policy Consider

ations Enunciated in the Civil Rights

Acts and Is Not Inconsistent With the

Language of Title VII.

As discussed above, Congress' purpose in

enacting a counsel fee provision as part of Title

VII was to encourage plaintiffs to bring litiga

tion. Clearly, a provision which would give

counsel fees as a matter of course to prevailing

defendants would defeat the congressional purpose,

13 -

since potential plaintiffs would have to weigh

the possibility of an award of significant

attorneys' fees against them even in a case which

presented substantial issues and which deserved

to be filed and prosecuted in court. The lower

courts have therefore adopted the rule that the

standard for assessing fees is different for

plaintiffs and defendants. Thus, in conformity

with Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, supra,

they have held that a prevailing defendant

may obtain counsel fees only when the court finds

that the action was brought in bad faith, for

vexatious reasons, and for the purpose of harass

ment. See, e.g. , Carrion v. Yeshiva University,

535 F.2d 722 (2d Cir. 1976); United States Steel

Corp. v. United States, 519 F.2d 359 (3rd Cir.

1975); Wright v. Stone Container Corp., 524 F.2d

1058 (8th Cir. 1975).

Petitioner seeks to refute these decisions

by maintaining that the plain meaning of the

statute shows that the standard for both plain

tiffs and defendants is to be the same; i.e. ,

since the statute makes no distinction on its

face, no distinction can be read into it by the

courts. We would urge that the statute is not

nearly as plain as petitioner contends, and that

the problem with petitioner's position is that

14 -

it focuses on the wrong part of the statute.

The fact that both parties may get counsel fees

on some occas ions, doe s not in any way, as

petitioner contends, mean that they are to get

them on the same basis. The part of the statute

which deals with that question is the language

stating that the court may "in its discretion"

award fees.

The question then becomes what standards

are to govern the court's discretion in a partic

ular case. The statute does not speak to that

specifically, certainly not in its language, and

it is wholly appropriate to turn to the legis

lative history for guidance as to what the

standards for the exercise of discretion should

be. When one does so, it becomes apparent

that the standards should not the same if the

court is deciding whether to grant counsel

fees for the plaintiff as opposed to granting

them for the defendant. As this Court has

discussed in Newman v Piggie Park, supra, as well

as in cases following it dealing with other

counsel fees statutes in civil rights cases, such

as Northcross v. Memphis Board of Education, 412

U.S. 427 (1973) and Bradley v. School Board of

Richmond, 416 U.S. 696 (1974), the standard for

prevailing plaintiffs is that counsel fees are

15 -

to be awarded except in unusual circumstances

so that the Congressional purpose of encouraging

litigation would be carried out. As we have

discussed at length above, to allow counsel fees

as a matter of curse to prevailing defendants

would have exactly the opposite effect and would

discourage litigation, and thus run contrary to

congressional purpose. Discouraging frivolous or

vexatious litigation, however, is wholly consis

tent with congressional purpose, both because no

valid purpose at all would be furthered by such

litigation, and by discouraging it the courts

would be free to focus their attention on those

cases which present substantial issues arising

under the civil rights laws.— ^

10/ During the Congressional debates, concern

was expressed that the counsel fees provision

could encourage "ambulance chasing", and could

lead to the bringing of frivolous law suits for

the purpose of obtaining a fee. In response, it

was pointed out that the "prevailing party"

language would permit an award to defendants in

vexatious and insubstantial suits and thus

discourage the bringing of totally unmeritorious

litigation. See, 110 Cong. Rec. 14201, 14213-14

(June 17, 1964).

16 -

Petitioner presents another argument that

allegedly supports its reading of the statute.

That is, if the standard for defendants is

harassment, bad faith, or vexatious litigation,

there is no need to have the statute read "prevail

ing party", since the defendant would be entitled

to counsel fees under that standard pursuant to

the American rule in any case. Thus, it is

argued, the statute would have no meaning

with regard to defendants. This conclusion does

not follow, however. If the statute read "prevail

ing plaintiffs" and counsel fees awards were

limited to such plaintiffs, then the statute

would bar counsel fees on behalf of defendants

under all circumstances. Under such a reading,

the American rule would be abrogated for defen

dants in civil rights cases since even in

instances where litigation was frivolous or

brought in bad faith they could not be awarded by

the courts.

It is certainly clear that Congress's view

now is that the standard should be different for

11/ See, e.g., Byram Concretanks, Inc, v. Warren

Concrete Products Co., 374 F.2d 649 (3rd Cir.

1967).

17 -

plaintiffs and defendants in civil rights cases.

In 1976 Congress passed the Civil Rights Attor

neys' Fees Act of 1976, designed to fill gaps

created by the decision of this Court in Alyeska

Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society,

421 U.S. 240 (1975). In that decision, this

Court disapproved decisions of the lower federal

courts applying the "private attorneys general"

standard, enunciated with regard to Title II and

20 U.S.C. §1617, to actions brought under 42

U.S.C. §1981, 1982 and 1983, the post-Civil War

. . . 12 /Reconstruction civil rights acts.— Congress

was concerned that this result created an anomaly

in that under the post-1964 civil rights acts

fees were awarded to plaintiffs as a matter of

course, whereas in pre-1964 civil rights act

cases counsel fees were awardable only under

the much more restrictive American rule. As was

pointed out in the committee reports, and often

during the debates on the 1976 Act, employment

discrimination cases could be brought either under

1 3/§1981 or under Title VII.— 'However, under the

12/ 421 U.S. at 270, n.46.

13/ See H. Rep. No.94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d

Sess., pp. 2-5 ( 1976); S. Rep. No. 94-1011,

94th Cong., 2d Sess., pp. 1-4 (1976); 122 Cong.

Rec. H12165 (daily ed. Oct.l, 1976)(Remarks of

Rep. Seiberling).

18 -

Alyeska decision, counsel fees were awardable

only under Title VII. Thus, even though an action

might deal with the same issues and serve exactly

the same public purpose, counsel fees could not

be obtained.

It was specifically to clear up this

anomaly and to bring about uniformity for all

civil rights actions with regard to counsel fees

that the 1976 Act was p a s s e d . D u r i n g the

course of the enactment of the statute, in both

the House and the Senate extensive attention was

given to decisions of this and the lower courts

interpreting the counsel fees provisions under

the post-1964 Civil Rights Acts. Newman v.

14/ The Senate Report stated the purpose of

the Act thus:

This amendment to the Civil Rights

Act of 1866, Revised Statutes Section

722, gives the Federal courts discre

tion to award attorneys' fees to pre

vailing parties in suits brought to

enforce the civil rights acts which

Congress has passed since 1866. The

purpose of this amendment is to remedy

anomalous gaps in our civil rights

laws created by the United States

Supreme Court's recent decision in

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilder

ness Society, 421 U.S. 240 (1975), and

to achieve consistency in our civil

rights laws. S. Rep. 94-1011, 94th Cong.

2d Session, p. 1 (1976).

19 -

Piggie Park Enterprises, supra, was cited as

establishing the proposition that plaintiffs were

to be given counsel fees as a matter of course

when they prevai led Contrariwise, the

decisions in Carrion v. Yeshiva University, supra

and United States Steel Corp.v. United States,

supra, were cited as es tablishing that the

standard for defendants was dif ferent.— ^That

is, defendants were to obtain counsel fees only

when the action was found to be brought in bad

faith and for harassment.

Indeed, during the debates the question was

raised as to whether it was necessary to specify

"prevailing parties" if all the defendants could

get what they were entitled to under the American

rule to begin with. The answer was given that it

was not the Act's intent to foreclose defendants

from getting counsel fees under all circumstances.

It was pointed out that the United States had

suggested to the House committee that counsel

fees be limited to "prevailing plaintiffs". The

suggestion was rejected because Congress still

wished to deter frivolous lawsuits by plaintiffs,

15/ See, e.g., id. at p. 3

16/ See, id. at p. 5.

20 -

and thus allow defendants to get attorneys fees

under the standard which prevailed under the

American rule.-t^

In both the Committee reports and repeatedly

on the floor of the House and the Senate the

question of standards for awards of counsel fees

was discussed. It was consistently stated that

Congress intended that a different standard

apply, that it intended that the same standard

apply in the 1976 Act that was required by the

courts under their interpretation of the 1964

Act,and that the purpose was to bring about

uniformity with regard to all civil rights

actons. Thus, given this legislative history, it

is indisputable that, for example, in an action

brought under §1981 for equal employment, the

defendant could receive counsel fees only upon a

showing of bad faith and harassment. If a

contrary result were reached in the present

action, however, the wholly anomalous result would

be that there would again be a lack of uniformity

in the standards applied in civil rights cases.

Plaintiffs would simply be encouraged to file

IZ/ See, e.g.; 122 Cong. Rec. H12162 (daily ed.

Oct. 1, 1976 (Remarks of Rep. Kastenmeier); 122

Cong. Rec. S16491 (daily ed. Sept. 23, 1976)

(Remarks of Sen. Tunney).

21

their lawsuits under §1981 and thereby not to

file administrative complaints with the EEOC,

avoiding Title VII completely, a result that

would be who 1ly contrary to Congressional

intent.— ^

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of

the Court below should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN LEVENTHAL

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 C o l u m b u s C i r c l e

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

18/ Thus Rep. Railsback, one of the sponsors of

the bill, stated on the floor of the House just

prior to passage: "It is not the intent of Con

gress nor is it the intent of this statute to

encourage persons to sue directly under section

1981 rather than using the services provided by

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act.Congress has

established the EEOC to remedy individual com

plaints as well as patterns and practices of

illegal discrimination and has authorized the

Commission to sue on behalf of the plaintiffs."

122 Cong. Rec., H12161 (daily ed. Oct.1,1976).

MEILEN PRESS INC — N. Y. C. «sglS*»